Abstract

The erbB family of receptor tyrosine kinases are known to play important roles in both normal epithelial development and epithelial neoplasia. Considerable evidence also suggests that signaling through the EGFR plays an important role in multistage skin carcinogenesis in mice; however, less is known about the role of erbB2. In this study, to further examine the role of both erbB2 and EGFR in epithelial carcinogenesis, we examined the effect of a dual erbB2/EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI), GW2974, given in the diet on skin tumor promotion during two-stage carcinogenesis in both wild-type and BK5.erbB2 mice. In BK5.erbB2 mice, erbB2 is overexpressed in the basal layer of epidermis and leads to heightened sensitivity to skin tumor development. GW2974 effectively inhibited skin tumor promotion by 12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol-13-acetate (TPA) in both wild-type and BK5.erbB2 mice, although a more marked effect was seen in BK5.erbB2 mice. In addition, this inhibitory effect was reversible when GW2974 treatment was withdrawn. GW2974 inhibited TPA-induced epidermal hyperproliferation, which correlated with reduced activation of both the EGFR and erbB2. These results support the hypothesis that both the EGFR and erbB2 play an important role in the development of skin tumors during two-stage skin carcinogenesis, especially during the tumor promotion stage. Furthermore, the marked sensitivity of BK5.erbB2 mice to the inhibitory effects of GW2974 during tumor promotion suggest greater efficacy for this compound when erbB2 is overexpressed or amplified as an early event in the carcinogenic process.

Keywords: EGFR, erbB2, skin tumor, two-stage carcinogenesis

Introduction

A number of receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs) have been described (1–3). Among them, the erbB family of RTKs (EGFR, erbB2, erbB3, and erbB4) has been shown to be important in normal epidermal development, as well as in neoplasia (1, 4). The variety of post-receptor signaling pathways activated by ligand binding, including signaling through the Ras/MEK/MAPK/Erk (extracellular signal-regulated kinase), phospholipase Cγ, signal transducers and activators of transcription (STATs), and phosphatidylinositol-3 kinase (PI3K) pathways that are common to nearly all RTKs, is the result of both the diversity of ligands they bind and the heterodimerization that occurs between the various erbB family members (5, 6). Although all of the erbB family members share similarities in primary structures, receptor activation mechanisms, and signal transduction patterns, they bind to different ligands. Ligand-dependent activation of erbB family receptors can lead to both homodimerization and heterodimerization (7). To date, no ligand has been identified for erbB2 (8–11); it can only act as part of a heterodimer with a ligand-bound receptor, often EGFR or erbB3 (5, 6). In contrast, erbB3 cannot generate signals in isolation because the kinase function of this receptor is impaired, thus relying on interaction with erbB2 for subsequent downstream signaling events (12).

Considerable evidence exists demonstrating that signaling through the EGFR plays an important role during both two-stage and ultraviolet (UV) light-induced carcinogenesis in mouse skin (13–15). In previous experiments, we found that topical application of diverse tumor promoters elevated the mRNA and protein levels of EGFR ligands including transforming growth factor α (TGF-α), amphiregulin, and heparin-binding EGF-like growth factor (HB-EGF) (13). The expression levels (both mRNA and protein) of the EGFR and EGFR ligands were also constitutively elevated in primary papillomas and squamous cell carcinomas (SCCs) generated by an initiation-promotion regimen (13, 16). Studies with transgenic mice have shown that the overexpression of TGF-α in basal or suprabasal epidermal cells can substitute for ras activation and leads to epidermal hyperplasia (17–21). Papillomas develop following initiation with 7,12-dimethylbenz(a)anthracene (DMBA) in TGF-α transgenic mice, indicating that constitutive EGFR signaling can also substitute for the promotion stage of multistage skin carcinogenesis (18). Abrogation of EGFR function in keratinocytes has been shown to inhibit growth and development of skin tumors via reduction in proliferation of basal cells (22, 23). Finally, EGFR activation has been shown to be critical for UV-induced epidermal proliferation (24, 25) and inhibition of EGFR tyrosine kinase activity with AG1478 inhibited UV promotion of skin tumors in TG:AC mice (14).

In contrast to EGFR, less is known regarding the role of erbB2 in mouse skin carcinogenesis. We previously reported the activation of both EGFR and erbB2 and the presence of EGFR:erbB2 heterodimers in EGF-stimulated mouse keratinocytes, TPA-treated mouse epidermis, and the epidermis of K14.TGF-α transgenic mice (26). These results suggested the possibility that erbB2 may facilitate signaling through the EGFR during the tumor promotion stage of mouse skin carcinogenesis. To further study the role of erbB2 in skin and in skin tumor promotion and skin carcinogenesis, we and others developed transgenic mouse models in which an activated form of erbB2 (rat neu oncogene) was overexpressed in epidermis (27–29). In these transgenic lines, a dramatic phenotype was observed characterized by severe epithelial hyperplasia in multiple organs, including the skin, where hyperplasia of the hair follicles was particularly striking. To avoid the severity of this phenotype and shortened life span, we generated transgenic mice that overexpress wild-type rat erbB2 under the control of the BK5 promoter (BK5.erbB2 mice) (30). In BK5.erbB2 mice, the overexpression of wild-type rat erbB2 in the basal layer of epidermis led to increased proliferation and hyperplasia of both the follicular and interfollicular epidermis as well as sebaceous gland enlargement. In addition, these mice, especially those homozygous for the transgene, displayed significant alopecia as a result of the follicular changes observed. Homozygous BK5.erbB2 transgenic mice also developed spontaneous papillomas, some of which converted to squamous cell carcinomas. Both homo- and hemizygous BK5.erbB2 transgenic mice were also hypersensitive to the proliferative effects of the skin tumor promoter 12-0-tetradecanoylphorbol-13-acetate (TPA) and were more sensitive to two-stage carcinogenesis. More recently, Hansen and colleagues have shown that erbB2 signaling is also involved in the actions of UV in inducing epidermal proliferation and hyperplasia (31, 32) and that inhibition of erbB2 using AG825 blocked UV promotion of skin tumors in TG:AC mice (33).

In the current study, to further examine the role of both the EGFR and erbB2 in skin carcinogenesis, we examined the effect of a dual EGFR/erbB2 tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI), GW2974, on skin tumor promotion by TPA in both wild-type and BK5.erbB2 mice. Treatment with GW2974 throughout the tumor promotion stage resulted in a significant inhibition of tumor formation in both wild-type and BK5.erbB2 mice, although the effect was greater in the transgenic mice. Thus, GW2974 has substantial chemopreventive activity through blockade of EGFR/erbB2 signaling during skin tumor promotion. The greater efficacy of GW2974 in BK5.erbB2 mice suggests that this compound may be particularly effective in epithelial cancers where erbB2 is overexpressed or amplified early in the carcinogenesis process.

Materials and Methods

Tumor induction and treatment

Both wild-type and BK5.erbB2 mice (20 – 25 mice, 7 – 8 weeks of age, in each group) were shaved 2 days prior to initiation. Mice were initiated with 50 nmol of DMBA in 0.2 mL of acetone. The mice received either the semi-synthetic AIN76A control diet or AIN76A diet containing a supplement of 200 ppm GW2974 supplied by GlaxoSmithKline (Research Triangle, NC) beginning 2 weeks after tumor initiation. Two weeks later, a promotion regimen consisting of the topical application of 6.8 nmol of TPA in 0.2 mL of acetone two times per week was started. The group of mice receiving the GW2974 was divided into two groups, one of which received GW2974 for the entire experiment while the other was switched to AIN76A control diet after 19 and 9 weeks of TPA treatment in experiment #1 and experiment #2, respectively (Figure 1). At the end of each experiment, the mice were sacrificed by cervical dislocation and the tumors and skin were removed and either snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen for Western blot analysis or fixed with formalin for histological evaluation. All tissues were analyzed via histological analysis. The mice were examined throughout the experiment and tumor multiplicity (tumors per mouse), as well as tumor incidence, was recorded weekly.

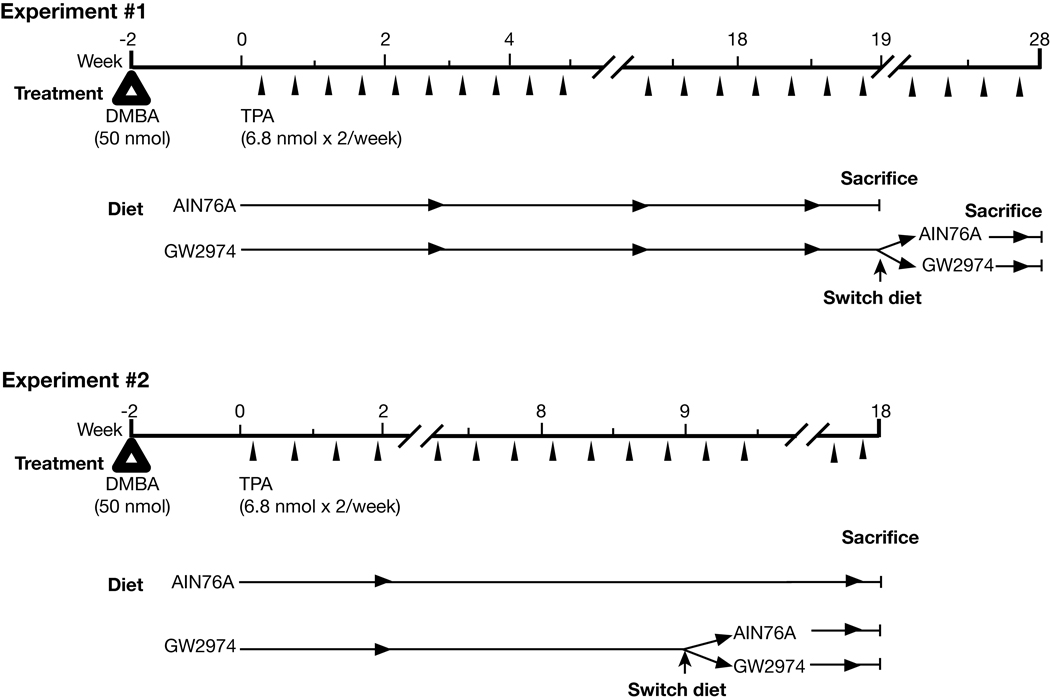

Figure 1.

Treatment protocols for dietary administration of GW2974 in Experiments #1 and #2 of the current study. In Experiment #1 each diet group had between 22–25 mice, and in Experiment #2 each diet group had between 22–24 mice.

Thirty minutes before sacrifice in both experiments, mice were injected with bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU, 100 µg/g of body weight). To evaluate systemic toxicity, body weight, feed consumption, and neurological function, the mice were physically assessed twice per week. All experiments were carried out with strict adherence to institutional guidelines for minimizing distress in experimental animals.

Immunofluorescence staining and Western blot analysis

The expression and localization of erbB2 and phospho-erbB2 (p-erbB2) were determined using immunofluorescence techniques on sections of skin as described previously (14). ErbB2 and p-erbB2 antibodies were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA) and Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA), respectively. The expression of erbB2, p-erbB2, EGFR and p-EGFR were also determined by Western blot analysis as described previously (30). All antibodies used for Western blot analysis were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology.

Histologic Evaluation

Dorsal skin samples and tumors were fixed in either formalin or ethanol and embedded in paraffin prior to sectioning. Sections of 4 µm were cut and stained with hematoxylineosin (H&E). Mice were injected i.p. with bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) in PBS (100 µg/g body weight) 30 min prior to sacrifice. For the analysis of epidermal labeling index (LI), paraffin sections were stained using anti-BrdU antibody as previously described (34). The LI is calculated by determining the percent of BrdU-labeled basal cells from observing ~2000 interfollicular epidermal basal cells. The determinations of epidermal thickness and LI were performed as previously described (35). For the analyses of the expression of keratin 1, keratin 5, keratin 6 and loricrin, tissues were fixed in ethanol and immunostained as previously described (36).

Detection of erbB2 mRNA Levels by Real Time PCR

ErbB2 mRNA transcript levels were assessed using fluorescent TaqMan™ methodology and an ABI Prism 7700 Sequence Detection System to quantify PCR amplification in real time as previously described (37).

Statistical Analysis

All of the data are expressed as the mean ± SD. Significant differences were determined using body weight change and the Student’s t-test for analysis of the levels of total and phosphorylated forms of erbB2 and EGFR in the Western blots. The Mann-Whitney U-test was used for analysis of epidermal thickness/LI and tumor incidence. P<0.05 was considered significant. All of the statistical analyses were done using StatView software (Abacus Concept Inc., Berkeley, CA).

Results

The effect of GW2974 on tumor promotion in wild-type and BK5.erbB2 mice during two-stage carcinogenesis

To determine the effects of GW2974 on skin tumor promotion during two-stage skin carcinogenesis, two independent experiments were performed as shown in Figure 1. The first tumor experiment (referred to as Experiment #1) was designed to examine the chemopreventive effect of GW2974 on tumor promotion in both wild-type and BK5.erbB2 mice, as well as the potential reversibility of this inhibitory effect after the tumor response had reached a plateau (i.e., after 19 weeks of promotion in this experiment). The second tumor experiment (referred to as Experiment #2) was again designed to determine the chemopreventive effects of GW2974 on tumor promotion and its reversibility. However, GW2974 treatment was stopped much earlier (i.e., after 9 weeks of promotion), before the tumor response had reached a plateau.

In Experiment #1, two groups of homozygous BK5.erbB2 transgenic mice and two groups of wild-type mice were initiated with DMBA (50 nmol), followed 2 weeks later by promotion with twice-weekly applications of TPA (6.8 nmol). Diets containing GW2974 were started two weeks after initiation with DMBA at the same time that promotion with TPA was begun. In addition, to determine the reversibility of the effects of GW2974 on tumor promotion, the diet of the groups treated with GW2974 was switched to AIN76A control diet after 19 weeks of promotion with TPA. The experiment was continued for an additional 9 weeks after the diets were switched, during which time TPA application was continued and the incidence and multiplicity (average number of tumors per mouse) of tumors were scored in each group. The results of the first 19 weeks of promotion with TPA in Experiment #1 are shown in Figure 2A (tumor multiplicity) and Figure 2B (tumor incidence). Homozygouos BK5.erbB2 mice fed the AIN76A control diet developed tumors faster and in greater number compared to wild-type mice fed the AIN76A control diet (Figure 2A). These results are similar to our previous studies using hemizygous BK5.erbB2 mice (30). The differences in tumor multiplicity between BK5.erbB2 and wild-type mice were significant at all time points as shown in Figure 2A (Mann-Whitney U-tests, P<0.05). In the group of homozygous BK5.erbB2 mice treated with GW2974, tumor promotion was almost completely blocked (5% tumor incidence and an average of 0.2 ± 0.04 tumors per mouse) compared to the 100% tumor incidence (and an average of 14.7 ± 3.0 tumors per mouse) found in the AIN76A control diet group by the end of the 19 week promotion period.

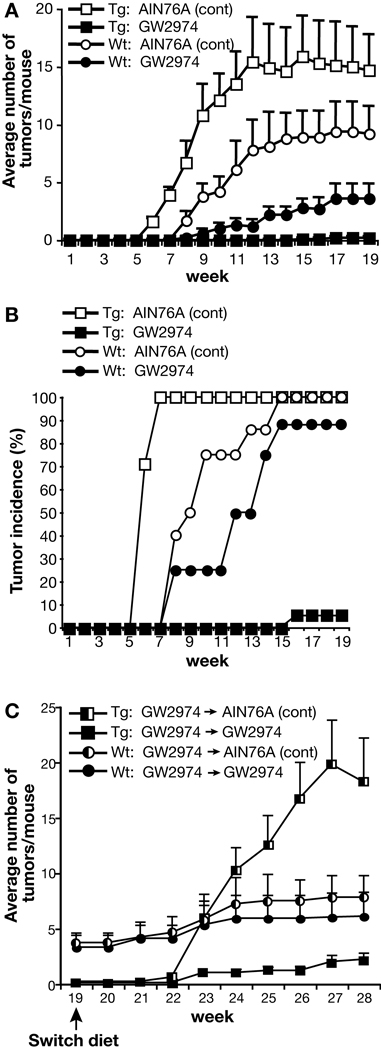

Figure 2.

Effects of GW2974 on skin tumor promotion in wild-type and BK5.erbB2 mice. (A) Number of tumors per mouse and (B) tumor incidence in Experiment #1. In Experiment #1, two groups of homozygous transgenic and two groups of wild-type mice were initiated with DMBA (50 nmol), followed two weeks later with twice-weekly applications of TPA (6.8 nmol).□, BK5.erbB2 mice fed AIN76A control diet; ■, BK5.erbB2 mice fed AIN76A diet containing 200 ppm GW2974; ○, Wild-type mice fed AIN76A control diet; ●, Wild-type mice fed AIN76A diet containing 200 ppm GW2974. (C). Average number of tumors per mouse after diet switch in wild-type mice (Wt) and BK5.erbB2 mice (Tg) in Experiment #1. □, BK5.erbB2 mice that were switched from GW2974 to AIN76A control diet; ■, BK5.erbB2 mice that were fed continuously with diet containing GW2974; ◐, Wild-type mice that were switched from GW2974 to AIN76A control diet; ●, Wild-type mice that were fed continuously with diet containing GW2974.

Wild-type mice treated with GW2974 also displayed significantly lower tumor incidence and tumor multiplicity. In this regard, the incidence of skin tumors was 100% and tumor multiplicity was 9.2 ± 2.3 in wild-type mice on the AIN76A diet at 19 weeks of promotion, whereas the incidence and multiplicity were 88% and 3.6 ± 1.2, respectively, in wild-type mice exposed to the GW2974 containing diet. Again, the difference in tumor multiplicity between the wild-type AIN76A control diet group and the GW2974 diet group was significant at all time points during the experiment as shown in Figure 2A (Mann-Whitney U-tests, P<0.05). Thus, both wild-type mice and BK5.erbB2 mice were responsive to inhibition of tumor promotion by dietary administration of GW2974, although it produced a significantly greater inhibitory response in BK5.erbB2 mice.

The BK5.erbB2 mice developed numerous large papillomas. Several of these papillomas upon gross examination appeared to have already undergone malignant conversion to squamous cell carcinomas by the end of the 19 week promotion period (not shown). Wild-type mice fed the AIN76A control diet developed exclusively papillomas and the tumors were slightly smaller in size and fewer in number (as noted above) compared to those of the BK5.erbB2 mice. However, GW2974 treatment dramatically inhibited growth of the tumors in both wild-type and BK5.erbB2 mice. In this regard, after 19 weeks of promotion, the average tumor sizes (tumor diameters) for the wild-type AIN76A control diet group, BK5.erbB2 AIN76A control diet group, wild-type GW2974 treatment group, and BK5.erbB2 GW2974 treatment group were (in mm) 3.1 ± 0.5, 3.5 ± 0.6, 1.5 ± 0.2, and 0.3 ± 0 (note that only one tumor developed in this latter group), respectively. The differences in tumor sizes between AIN76A and GW2974 diet groups for both genotypes were statistically significant (Mann-Whitney U-tests, p<0.05). As noted previously, homozygous BK5.erbB2 mice exhibited a gross phenotype characterized by partial alopecia and wrinkled skin (30). The homozygous BK5.erbB2 mice treated with GW2974 also showed reversal of the alopecia with a more typical looking hair coat.

At the end of the 19 week promotion period, the two groups of mice that had been fed AIN76A control diet were sacrificed and the two groups of mice that had been treated with GW2974 were each divided into two separate groups (see again Figure 1). One of these groups continued to be treated with GW2974 while the other was fed the AIN76A control diet without GW2974 in order to determine whether the inhibitory effect on tumor promotion was reversible. Four weeks after the diet was switched from GW2974 to AIN76A control diet, the BK5.erbB2 mice started to develop tumors and the average number of tumors per mouse rose quickly (Figure 2C). In the group of BK5.erbB2 mice that continued to be treated with GW2974, this compound still showed a potent inhibitory effect on tumor development. In wild-type mice, the average number of tumors increased gradually regardless of whether the diet was switched to AIN76A or remained as the GW2974 diet.

At the end of Experiment #1 (i.e., 9 weeks after the diet was switched), the average number of tumors per mouse in the BK5.erbB2 mice fed AIN76A control diet (after being switched from GW2974) and BK5.erbB2 mice treated with GW2974 continuously were 18.2 ± 4.8 and 2.2 ± 0.6, respectively. This difference was highly significant (Mann Whitney U test, P<0.05). Furthermore, at the end of the experiment, the average number of tumors in the wild-type mice fed the AIN76A control diet after being switched from GW2974 and wild-type mice treated with GW2974 continuously were 7.5 ± 2.0 and 6.1 ± 2.2, respectively. These differences, however, were not statistically significant (P>0.05). These results indicate that GW2974 had a potent inhibitory effect on the development of skin tumors when administered during the tumor promotion stage of a two-stage carcinogenesis protocol. Additionally, this inhibitory effect was reversible in the BK5.erbB2 mice, and partially reversible in wild-type mice under the conditions and during the time frame of Experiment #1.

In Experiment #2, the diets were switched substantially earlier than in Experiment #1 in order to further examine the potential reversibility of the effects of GW2974 on tumor promotion at an earlier stage before the tumor response reached a plateau. The average number of tumors per mouse in this experiment was similar to that of the first experiment at the time of diet switch (i.e., at the 9th week of TPA promotion) (Figure 3A). Again, BK5.erbB2 mice fed the AIN76A control diet developed tumors faster and in greater number compared to wild-type mice fed the AIN76A control diet. Likewise, GW2974 significantly (P<0.05) inhibited tumor promotion in both BK5.erbB2 and wild-type mice at 9 weeks of promotion. In this regard, the average number of tumors was 19.3 ± 3.9 and 1.0 ± 0.3 in BK5.erbB2 mice on AIN76A and GW2974 diet, respectively, and 2.8 ± 1.0 and 1.8 ± 0.5 in wild-type mice on AIN76A and GW2974 diet, respectively. At the 9th week of promotion, both wild-type and BK5.erbB2 mice exposed to GW2974 were divided into two groups to determine the reversibility of the effects of GW2974 on skin tumor promotion. Thus, as in Experiment #1, the wild-type and BK5.erbB2 mice were either maintained on the GW2974 diet or switched to AIN76A. All four groups of mice were then sacrificed 9 weeks after the diet switch.

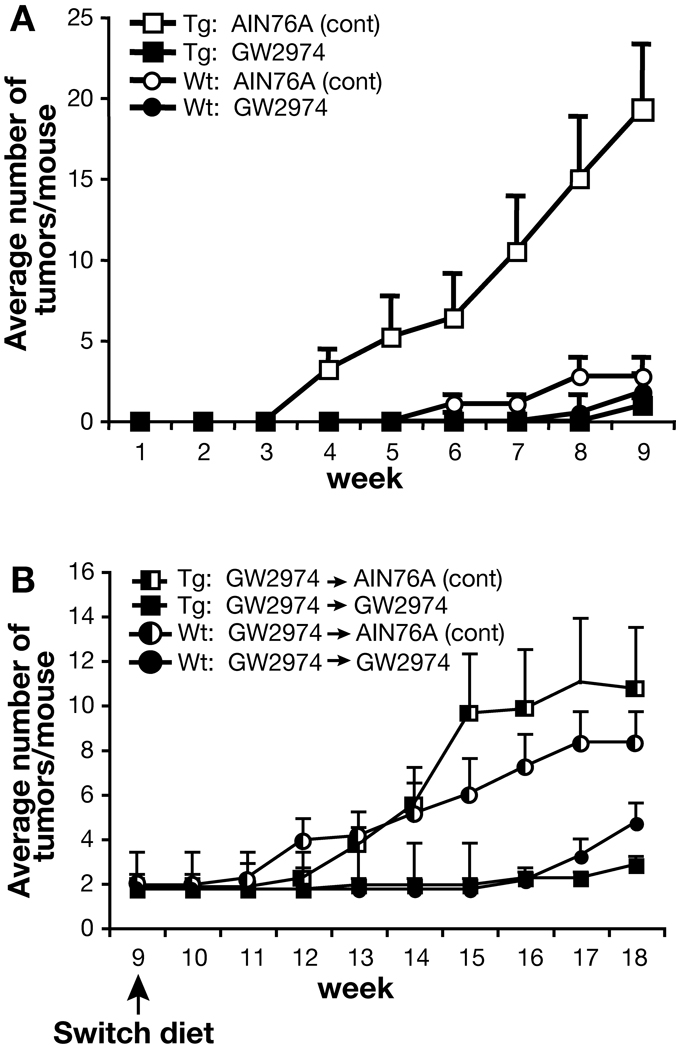

Figure 3.

Effect of GW2974 on skin tumor promotion in wild-type and BK5.erbB2 mice in Experiment #2. (A) Number of tumors per mouse in Experiment #2. □, BK5.erbB2 mice fed AIN76A control diet; ■, BK5.erbB2 mice fed AIN76A diet containing GW2974; ○, Wild-type mice fed AIN76A control diet; ●, Wild-type mice fed AIN76A diet containing GW2974. (B) Number of tumors per mouse after diet switch in wild-type (Wt) and BK5.erbB2 mice in Experiment #2. ◐, Wild-type mice that were switched from GW2974 to AIN76A◧ control diet; ●, Wild-type mice that were fed continuously with diet containing GW2974; , BK5.erbB2 mice that were switched from GW2974 to AIN76A control diet; ■, BK5.erbB2 mice that were fed continuously with diet containing GW2974.

As shown in Figure 3B, tumors began to arise within a few weeks following switch to AIN76A in both wild-type and BK5.erbB2 mice. At the end of the diet switch observation period, the average number of tumors per mouse in those two groups was 8.3 ± 1.4 and 10.7 ± 2.8, respectively. In contrast, the number of tumors per mouse in the groups of mice fed the GW2974 continuously remained significantly lower at the end of the additional 9 week observation period. These results from Experiment #2 further indicate the reversibility of the inhibitory effect of GW2974 on tumor promotion in BK5.erbB2 mice regardless of the timing, although the effect observed in this experiment was not as great as that seen in Experiment #1. The results of this experiment also suggest greater reversibility of the effects of GW2974 in wild-type mice earlier in the tumor promotion process before the papilloma response reaches a plateau.

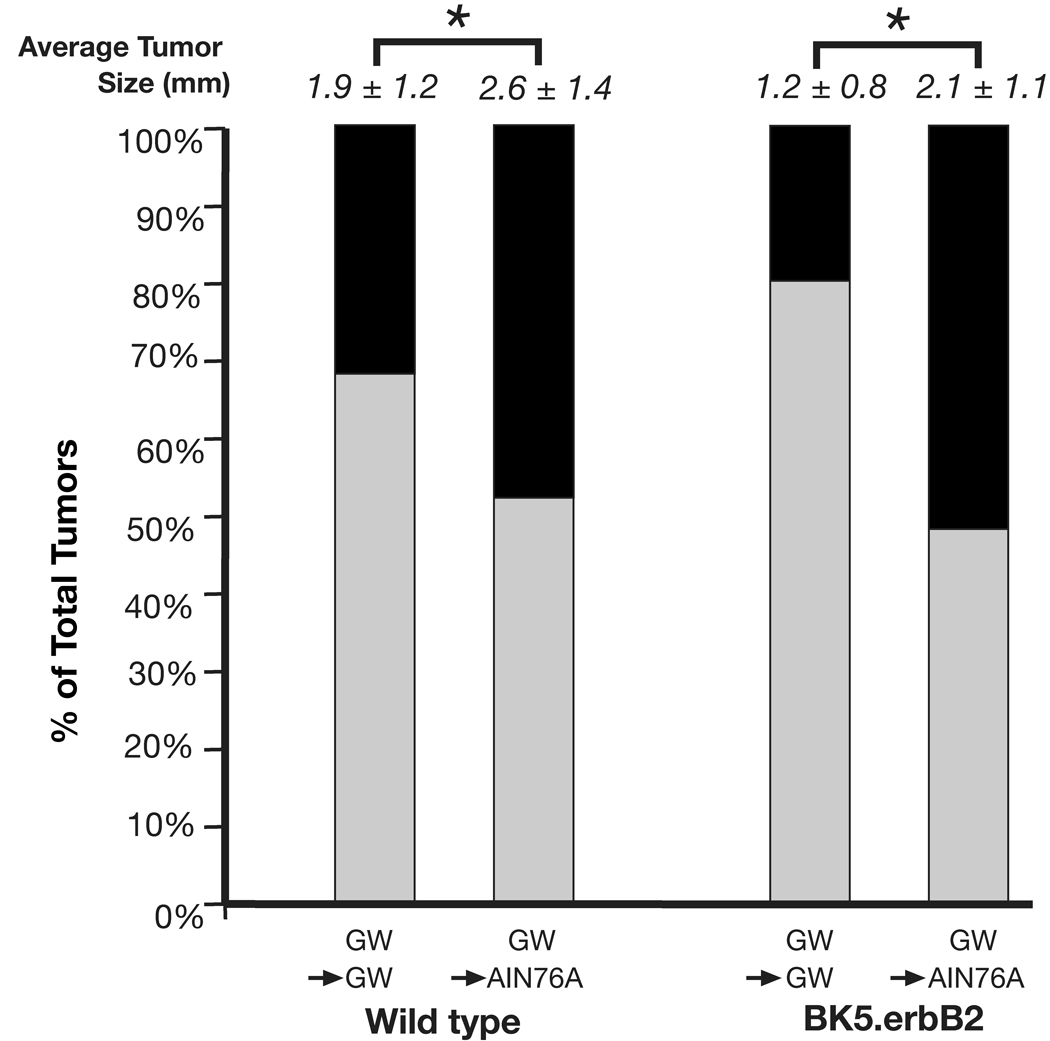

Figure 4 summarizes the average tumor sizes (i.e., diameters) at the end of Experiment #2. As shown, the size of skin tumors was significantly smaller in both BK5.erbB2 and wild-type mice treated continuously with GW2974 compared with mice switched to the AIN76A control diet. Throughout the experiment, none of the wild-type or BK5.erbB2 mice treated with GW2974 showed any signs of toxicity or neurological abnormalities. As shown in Table 1, body weights either remained similar in the different diet groups or increased over the course of the experiment.

Figure 4.

Tumor size (diameter) and categorization by size at the end of Experiment #2. Tumor diameters were measured in week 18 at the end of Experiment #2. ■, tumors > 2 mm in diameter; □, tumors ≤ 2 mm in diameter. * p < 0.05

Table 1.

Average body weight changes in wild-type and BK5.erbB2 mice fed AIN control diet, or switched from one to the other.

| Body Weight Changes | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mouse | Treatment | Average Gain ± SD |

||

| Wt | AIN → AIN | 12.3 ± 4.6 |

* *

|

* *

|

| AIN → GW | 12.5 ± 5.9 | |||

| GW → GW | 13.4 ± 1.5 |

* *

|

||

| GW → AIN | 13.9 ± 4.9 | |||

| BK5.erbB2 | AIN → AIN | 4.4 ± 3.9 |

* *

|

* *

|

| AIN → GW | 7.9 ± 2.9 | |||

| GW → GW | 5.0 ± 4.4 |

* *

|

||

| GW → AIN | 6.1 ± 2.8 | |||

P < 0.05 (two sample t-test)

Significant differences were determined using an independent two-sample t-test. A value of p < 0.05 was considered to be significant.

Impact of GW2974 on epidermal hyperplasia and proliferation

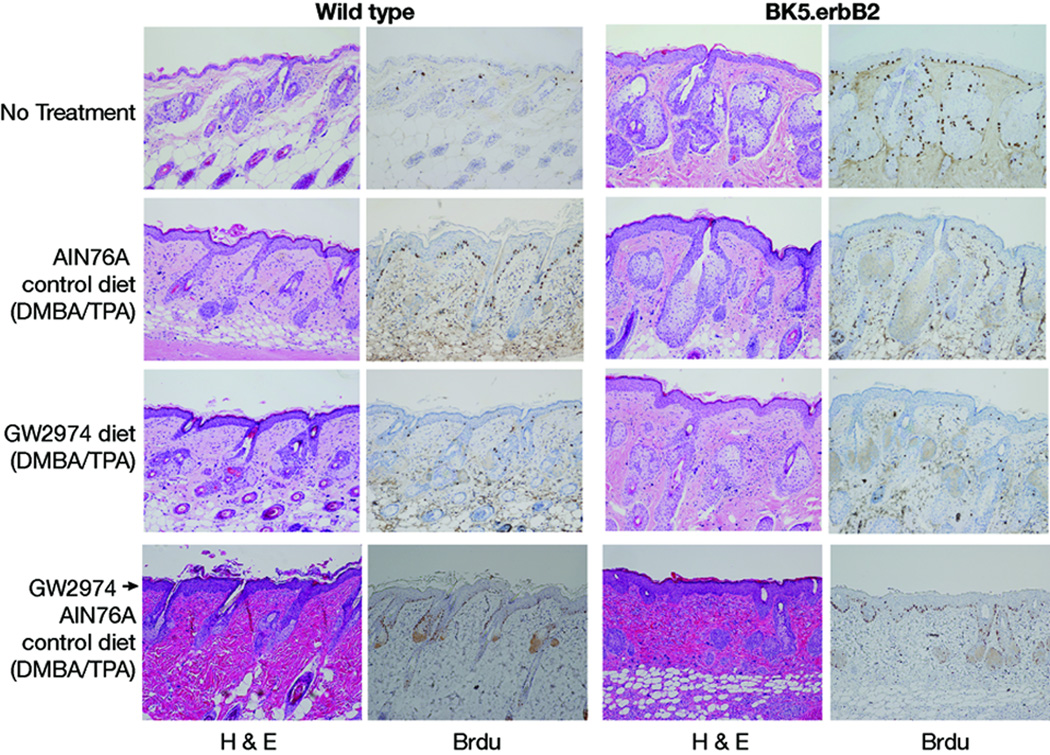

The impact of GW2974 treatment on epidermal hyperplasia and proliferation in Experiment #2 is shown in Figure 5 and Table 2. For the data presented, non-tumorous dorsal skin tissue was collected at the end of the experiment. Figure 5 shows representative H&E- and BrdU-stained sections from wild-type and BK5.erbB2 mice fed either AIN76A control or GW2974 diet continuously or GW2974 followed by AIN76A. Table 2 summarizes the epidermal thickness determined from H&E stained sections and labeling indices (LI) determined from BrdU staining in all groups of wild-type and BK5.erbB2 mice from Experiment #2 of a similar age. As expected, untreated BK5.erbB2 mice maintained on the AIN76A diet showed a 3.6- and 5.7-fold increase in epidermal thickness and LI, respectively, compared to that of wild-type mice on the same control diet. In the DMBA/TPA treated groups continuously fed the AIN76A control diet there were no significant differences in either epidermal thickness or LI between wild-type and BK5.erbB2 mice. Both wild-type and BK5.erbB2 mice treated with the DMBA/TPA protocol and maintained continuously on GW2974 had significantly reduced epidermal hyperplasia and LI compared to the corresponding AIN76A control diet groups. Finally, in the groups switched from GW2974 to AIN76A diets, the epidermal hyperplasia and LI partially reversed toward the value seen in mice continuously fed the AIN76A diet during the two-stage protocol. Collectively, these data indicate that GW2974 significantly blocked TPA-induced epidermal proliferation in both wild-type and BK5.erbB2 mice, although the magnitude of these inhibitory effects was again greater in the transgenic mice.

Figure 5.

H&E and BrdU stained sections of skin from wild-type and BK5.erbB2 mice treated with various diets in Experiment #2. Skins were collected at the end of Experiment #2 (i.e., at week 18).

Table 2.

Comparison of the effects of AIN76 control and GW2974 diets on epidermal hyperplasia and cell proliferation in wild type and BK5.erbB2 mice.

| Mouse | Treatment | Diet Initial |

Final | Epidermal Thickness |

Labeling Index (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wild-type | Acetone/ Control |

AIN76A | AIN76A | 7.8 ± 0.4 a,b,c | 1.8 ± 0.2 a,b,c |

| DMBA/TPA | AIN76A | AIN76A | 70.4 ± 3.5 a,d | 74.2 ± 4.8 a,d | |

| DMBA/TPA | GW | GW | 34.4 ± 3.7 b | 24.4 ± 3.5 b | |

| DMBA/TPA | GW | AIN76A | 40.1 ± 3.8 | 45.4 ± 3.7 | |

| Tg | Acetone/ Control |

AIN76A | AIN76A | 28.4 ± 2.6 a,c | 10.2 ± 2.5 a,c |

| DMBA/TPA | AIN76A | AIN76A | 78.6 ± 3.9 a,d | 68.4 ± 5.1 a,d | |

| DMBA/TPA | GW | GW | 28.4 ± 3.1 e | 14.4 ± 2.2 e | |

| DMBA/TPA | GW | AIN76A | 56.7 ± 4.4 e | 47.8 ± 3.3 e | |

Values in table represent ± SD.

The difference in epidermal thickness and LI value were found to be statistically significant (P<0.01) by the U-Whitney U-test.

Significant difference between acetone-treated (AIN76A-AIN76A diet) group and DMBA/TPA-treated (AIN76A-AIN76A diet) group

Significant difference between acetone-treated (AIN76A-AIN76A diet) group and DMBA/TPA-treated (GW-GW diet) group

Significant difference between wild type (acetone-treated, AIN76A-AIN76A) and transgenic (acetone-treated, AIN76A-AIN76A) mice

Significant difference between DMBA/TPA-treated (AIN76A-AIN76A) group and DMBA/TPA- treated (GW-GW) group

Significant difference between DMBA/TPA-treated (GW-GW) group and DMBA/TPA-treated (GW-AIN76A) group

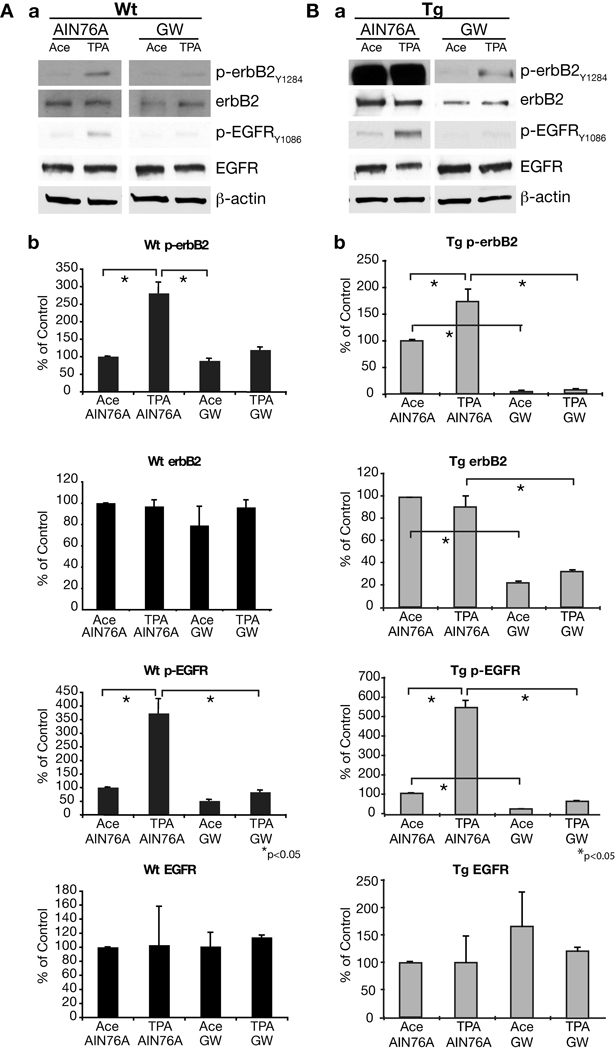

Status of erbB2 and EGFR in skin of GW2974-treated mice

To further investigate the mechanisms for the effects of GW2974 on skin tumor promotion in both wild-type and BK5.erbB2 mice, Western blot analyses were performed. For these experiments, mice were maintained on either the AIN76A or GW2974-supplemented diet for a period of 4 weeks. At this point, mice were treated with TPA (twice weekly for two weeks) and epidermal protein lysates from wild-type and BK5.erbB2 mice were collected 4 hours after the last treatment with TPA. As previously shown (30), the levels of p-erbB2 and p-EGFR were significantly higher in the epidermis of BK5.erbB2 mice compared to the epidermis of wild-type mice (Figure 6). Note that the Western blot of p-erbB2, erbB2, and p-EGFR from wild-type mice needed a significantly longer exposure time compared to blots generated using epidermal lysates from BK5.erbB2 mice. Following treatment with TPA, the levels of p-erbB2 and p-EGFR were further increased in epidermis of both wild-type and BK5.erbB2 mice (see again Figure 6). Treatment with GW2974 significantly reduced the levels of total erbB2 protein and the phosphorylation of both erbB2 and EGFR in the epidermis of untreated and TPA-treated BK5.erbB2 mice. Treatment with GW2974 also resulted in a significant decrease in the levels of p-erbB2 and p-EGFR in the epidermis of TPA-treated wild-type mice, although there were no significant effects on the levels of total erbB2 and EGFR protein. The reductions in p-erbB2 and total erbB2 protein in BK5.erbB2 mice as a result of treatment with GW2974 were confirmed by immunohistochemical analysis (Figure 7).

Figure 6.

Western blot analysis of the levels of total and phosphorylated erbB2 and EGFR in the dorsal skin. (A) Skin from wild-type mice fed with AIN76A or GW2974. (B) Skin from BK5.erbB2 mice fed with AIN76A or GW2974 diet. A group of four mice received four topical applications (given twice-weekly) of either 6.8 nmol TPA or acetone over 2 weeks and were sacrificed 4 h after the last treatment. Mice were fed with either AIN76A control diet or GW2974 containing diet from 2 weeks prior to the first TPA or acetone treatment until the end of the experiment. (a) Representative Western blots. (b) Relative expression levels measured via densitometry normalized to β-actin levels. Note that the Western blot of p-erbB2, erbB2 and p-EGFR from wild-type mice needed significantly longer exposure time to develop the film compared to erbB2 mice. *p <0.05

Figure 7.

Immunostaining for erbB2 and p-erbB2 in the skin of wild-type mice and BK5.erbB2 mice fed with AIN76A and GW2974 diets. Skin was collected from the experiment shown in Figure 6. Upper panels: Skin from a wild-type mouse on AIN76A diet treated with acetone. Middle panels: Skin from a BK5.erbB2 mouse on AIN76A diet treated with acetone. Lower panels: Skin from BK5.erbB2 mice on GW2974 diet treated with acetone.

Status of erbB2 mRNA in skin of GW2974-treated mice

In light of the data in Figure 5 showing that GW2974 treatment led to decreased levels of total erbB2 protein, we examined the levels of both mouse (i.e., endogenous) and rat (i.e., transgene) erbB2 mRNA as shown in Table 3. For this experiment, skins from groups of 4 mice each (both wild-type and BK5.erbB2 mice maintained on control diet and GW2974 containing diet from Experiment #1) were collected and total RNA was isolated. Levels of erbB2 mRNA were determined by quantitative RT-PCR. Rat erbB2 mRNA was only detected in skin from BK5.erbB2 mice and was not markedly decreased in the GW2974 treated group compared to that of untreated mice. The relative percentage mRNA level in BK5.erbB2 mice treated with GW2974 was 92 ± 10% compared to that of the untreated control group (100%) (see Table 3). In wild-type mice, treatment with GW2974 resulted in a slight reduction in the level of mouse (endogenous) erbB2 mRNA (90 ± 7%) compared to wild-type on the control diet. This slight reduction also was not statistically significant. In BK5.erbB2 mice, the level of mouse erbB2 mRNA was significantly lower in the control diet group (48 ± 4%) compared to wild-type mice on the control diet (Table 3, p<0.05). Thus, GW2974 did not appear to alter expression of the rat erbB2 transgene. The reduction in the level of endogenous erbB2 mRNA in BK5.erbB2 mice maintained on the control diet may be due to high levels of transgene mRNA and protein, however this possibility will require further experimentation to confirm.

Table 3.

Average relative erbB2 mRNA expression in skins from wild-type (WT) and BK5.erbB2 mice (TG) fed AIN76A control diet or GW2974 containing diet as determined by real time PCR analysis.

| WT control diet |

WT GW diet |

TG control diet |

TG GW diet |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rat mRNA (%) | 0 | 0 | 100 | 91.8 ± 9.7 |

| Mouse mRNA (%) |

100 | 89.8 ± 7.0 | 47.5 ± 4.2 | 83.25 ± 8.7 |

Four skins from each group (both wild-type and BK5.erbB2 mice maintained on control diet and GW2974 containing diet from Experiment #1) were collected and analyzed for erbB2 mRNA transcript levels. Mouse erbB2 mRNA levels are expressed as a percentage relative to WT mice fed control diet (AIN76A). Rat erbB2 mRNA levels are expressed as a percentage relative to TG mice fed control diet.

Discussion

The present study has investigated the impact of inhibiting both the EGFR and erbB2 during the tumor promotion stage on development of skin tumors in a two-stage skin carcinogenesis protocol. This was accomplished by determining the effects of orally administered GW2974, a dual specific tyrosine kinase inhibitor on skin tumor promotion in both BK5.erbB2 and wild-type mice. The major findings of this study are: i) GW2974 showed a potent chemopreventive effect on skin tumor promotion by TPA in both BK5.erbB2 and wild-type mice; ii) the inhibitory effect was more reversible early during tumor promotion in wild-type mice when GW2974 treatment was switched to control diet, whereas the inhibitory effects of GW2974 on tumor promotion in BK5.erbB2 mice were highly reversible regardless of the timing; (iii) GW2974 showed a potent inhibitory effect on TPA-induced epidermal proliferation as determined by epidermal thickness and BrdU incorporation in both BK5.erbB2 and wild-type mice. The magnitude of these effects was again greater in BK5.erbB2 mice; and iv) the chemopreventive effects of GW2974 on skin tumor promotion were associated with a significant reduction in activation of both the EGFR and erbB2. Collectively, these data indicate that targeting both the EGFR and erbB2 may be an effective strategy for prevention of epithelial cancers where signaling through this pathway is upregulated early in the carcinogenic process. Furthermore, drugs that possess dual specificity such as GW2974 may be more efficacious when erbB2 is overexpressed or amplified early during the carcinogenesis process.

As noted in the Introduction, considerable evidence suggests an important role for the EGFR in the development of skin tumors in mice undergoing two-stage and UV skin carcinogenesis. In normal human skin, immunohistochemical analyses showed that EGFR expression was detected predominantly in the basal layer of epidermis and decreased towards the corneum layer (38, 39). EGFR expression was also found in sebocytes, outer root sheath cells of hair follicles, smooth muscle cells of arrector pili, and dermal arteries (38, 39). Overexpression of EGFR protein has been reported in approximately 50 to 100% of basal cell carcinomas (BCCs) (40) and 90 to 100% of SCCs (40, 41), as determined by immunohistochemical analysis. Highly elevated mRNA levels of EGFR were reported in 38, 57, and 80% in normal epidermis, BCCs, and SCCs, respectively (42). In contrast, other studies have reported that the levels of EGFR protein in BCCs, SCCs, and normal epidermis were all similar (43, 44). It has also been reported that amplification of EGFR is observed in ~20% of SCCs, as determined by Southern blot (45). Elevation of EGFR ligands and EGFR activation (as detected by phosphorylation at Tyr1068) was also reported to be elevated in SCCs compared to BCCs and normal skin (43). Finally, UV exposure to both cultured human keratinocytes and human skin leads to activation of the EGFR (46–49). Thus, considerable evidence exist that activation of the EGFR plays a role in skin tumor development (especially SCCs) in humans. These data also suggest that the EGFR is a potential target for prevention of human skin cancer.

Although there has been intensive research regarding erbB2 and its role in many cancers, including breast, colorectal, cervical, biliary tract, HNSCC, testicular, ovary, stomach, urinary bladder, lung, osteosarcoma, and childhood medulloblastoma (50), relatively little is known about the role of erbB2 in human skin cancer. In normal human epidermis, erbB2 stains in the cytoplasm of cells in the basal layer and in the plasma membrane of cells in the upper suprabasal layers (51–53). ErbB2 is also found in the external root sheath of hair follicles and in eccrine gland secretory cells (54). In terms of cutaneous carcinomas, Lebeau et al. showed that in SCCs, the subcellular distribution of erbB2 remains unchanged (localized primarily in plasma membrane and cytoplasm), but in basal cell carcinomas (BCCs), erbB2 is distributed from the plasma membrane into cytosolic aggregates (51). In another study, it was reported that normal human skin, keratoacanthomas and actinic keratoses showed no or barely detectable erbB-2 protein expression; however, the outer epidermal layer of SCCs showed a few strongly positive cells (55). This study also showed that 20 of the 24 cases of SCC examined had elevated expression of erbB2 whereas only five of the 10 cases of BCC stained for erbB2 and more weakly than seen in SCCs. Thus, the expression patterns and exact role of erbB2 in normal human skin remains somewhat unclear; however, overexpression of erbB2 may play a role in the malignant conversion of keratinocytes. As noted in the Introduction and as shown in the current study, erbB2 appears to play an important role in both chemically- and UV-mediated skin carcinogenesis in mice (26–33).

To further explore the role of EGFR/erbB2 signaling in the development of skin tumors in both BK5.erbB2 and wild-type mice, we used GW2974, a dual EGFR/erbB2 tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI). GW2974 belongs to an orally active quinazoline group of TKIs and inhibits both EGFR and erbB2 by targeting the ATP binding sites of these molecules. GW2974 showed a potent inhibitory effect on cells overexpressing both EGFR and erbB2 in vitro and in a tumor xenograft model (56). In an earlier study, we reported significant chemopreventive and therapeutic efficacy of GW2974 given in the diet on gallbladder carcinoma that developed in BK5.erbB2 mice (57). In the current study, an almost complete chemopreventive efficacy was observed in BK5.erbB2 mice and a potent chemopreventive effect in wild-type mice was observed after treatment with GW2974 during the tumor promotion stage in a two-stage skin carcinogenesis protocol. This inhibition was reversible when GW2974 was withdrawn from the diets early in the process of tumor development of both wild-type and BK5.erbB2 mice. In addition, treatment of both BK5.erbB2 and wild-type mice with GW2974 diet resulted in a significant reduction in activation of both the EGFR and erbB2 during tumor promotion by TPA. These results indicate that the significant inhibitory effect of GW2974 on the development of skin tumors is due primarily to its ability to block the activation of both EGFR and erbB2 and inhibition of epidermal hyperproliferation during tumor promotion. The greater efficacy of GW2974 in BK5.erbB2 mice may be due to its ability to reduce both erbB2 protein levels as well as p-erbB2 levels. The ability of GW2974 to reduce erbB2 and p-erbB2 levels in BK5.erbB2 mice was not due to an effect on transgene expression as shown in Table 3.

In the present study, we chose to analyze the dual specific inhibitor GW2974. This decision was based on our previous findings that both the EGFR and erbB2 are activated in keratinocytes exposed to EGFR ligands or TPA (26, 58) and that exposure to EGFR ligands or TPA increases EGFR/erbB2 heterodiomer formation (26). In addition, two different EGFR selective inhibitors blocked TPA-induced epidermal hyperproliferation (58). Data in the literature support the hypothesis that erbB2 is the preferred partner for activated EGFR (5, 6, 59, 60). This interaction also reduces the rate of EGFR degradation (61). Thus, selectively blocking the EGFR should also be effective at reducing both EGFR activation as well as erbB2 activation and therefore block TPA-induced skin promotion. The data showing inhibition of TPA-induced epidermal hyperproliferation by EGFR-selective tyrphostins supports this hypothesis (58). In addition, preliminary data from our lab shows that mice fed a diet containing a specific inhibitor for the EGFR, gefitinib (400 ppm for one month), significantly reduced levels of both p-EGFR as well as total and p-erbB2 protein in the skins of both wild-type and BK5.erbB2 mice (unpublished). Based on this, it is likely that selective EGFR inhibitors would also be effective at blocking both EGFR and erbB2 activation and skin tumor promotion by TPA. The suppression of UVB-mediated skin tumor promotion in TG:AC mice by either an EGFR or an erbB2 TKI also supports this hypothesis (14, 33).

In conclusion, the current study demonstrates that a dual erbB2/EGBFR TKI, GW2974, effectively inhibited skin tumor promotion in both BK5.erbB2 and wild-type mice, when given orally via the diet. The effects of GW2974 were essentially reversible although reversibility occurred to a lesser extent in wild-type mice with a longer duration of skin tumor promotion. A more marked effect of GW2974 was seen in BK5.erbB2 mice, suggesting greater efficacy for this compound when erbB2 is overexpressed or amplified as an early event in the carcinogenic process. Targeting the EGFR or both EGFR and erbB2 may be an effective strategy for prevention of epithelial cancer, including skin cancer, when signaling through the EGFR and erbB2 pathway is upregulated early in the carcinogenic process.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NCI grant CA076520 and CA037111 (to J. DiGiovanni), The University of Texas M.D. Anderson Cancer Center Support Grant CA16672 and The National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences Center Grant ES07784. TM was supported by NIEHS training grant ES007247.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aaronson SA. Growth factors and cancer. Science. 1991;254:1146–1153. doi: 10.1126/science.1659742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schlessinger J, Ullrich A. Growth factor signaling by receptor tyrosine kinases. Neuron. 1992;9:389–391. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(92)90177-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ullrich A, Schlessinger J. Signal transduction by receptors with tyrosine kinase activity. Cell. 1990;61:203–212. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90801-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gullick WJ. Prevalence of aberrant expression of the epidermal growth factor receptor in human cancers. Br Med Bull. 1991;47:87–98. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.bmb.a072464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Graus-Porta D, Beerli RR, Daly JM, Hynes NE. ErbB-2, the preferred heterodimerization partner of all ErbB receptors, is a mediator of lateral signaling. Embo J. 1997;16:1647–1655. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.7.1647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Karunagaran D, Tzahar E, Beerli RR, et al. ErbB-2 is a common auxiliary subunit of NDF and EGF receptors: implications for breast cancer. Embo J. 1996;15:254–264. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pinkas-Kramarski R, Soussan L, Waterman H, et al. Diversification of Neu differentiation factor and epidermal growth factor signaling by combinatorial receptor interactions. Embo J. 1996;15:2452–2467. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Beerli RR, Hynes NE. Epidermal growth factor-related peptides activate distinct subsets of ErbB receptors and differ in their biological activities. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:6071–6076. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.11.6071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.King CR, Borrello I, Bellot F, Comoglio P, Schlessinger J. Egf binding to its receptor triggers a rapid tyrosine phosphorylation of the erbB-2 protein in the mammary tumor cell line SK-BR-3. Embo J. 1988;7:1647–1651. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1988.tb02991.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Plowman GD, Culouscou JM, Whitney GS, et al. Ligand-specific activation of HER4/p180erbB4, a fourth member of the epidermal growth factor receptor family. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90:1746–1750. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.5.1746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sliwkowski MX, Schaefer G, Akita RW, et al. Coexpression of erbB2 and erbB3 proteins reconstitutes a high affinity receptor for heregulin. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:14661–14665. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Citri A, Skaria KB, Yarden Y. The deaf and the dumb: the biology of ErbB-2 and ErbB-3. Exp Cell Res. 2003;284:54–65. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4827(02)00101-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kiguchi K, Beltran L, Rupp T, DiGiovanni J. Altered expression of epidermal growth factor receptor ligands in tumor promoter-treated mouse epidermis and in primary mouse skin tumors induced by an initiation-promotion protocol. Mol Carcinog. 1998;22:73–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.El-Abaseri TB, Fuhrman J, Trempus C, Shendrik I, Tennant RW, Hansen LA. Chemoprevention of UV light-induced skin tumorigenesis by inhibition of the epidermal growth factor receptor. Cancer Res. 2005;65:3958–3965. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-2204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kiguchi K, Beltran L, Dubowski A, DiGiovanni J. Analysis of the ability of 12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol-13-acetate to induce epidermal hyperplasia, transforming growth factor-alpha, and skin tumor promotion in wa-1 mice. J Invest Dermatol. 1997;108:784–791. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12292237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rho O, Beltran LM, Gimenez-Conti IB, DiGiovanni J. Altered expression of the epidermal growth factor receptor and transforming growth factor-alpha during multistage skin carcinogenesis in SENCAR mice. Mol Carcinog. 1994;11:19–28. doi: 10.1002/mc.2940110105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dominey AM, Wang XJ, Gagne TA. Targeted overexpression of TGFa in the epidermis of transgenic mice elicits anomalous differentiation and spontaneous, self-regressing papillomas. Cell Growth Differ. 1993;4:1071–1082. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jhappan C, Takayama H, Dickson RB, Merlino G. Transgenic mice provide genetic evidence that transforming growth factor a promotes skin tumorigenesis via H-Ras-dependent and H-Ras-independent pathways. Cell Growth Differ. 1994;5:385–394. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vassar R, Fuchs E. Transgenic mice provide new insights into the role of TGF-alpha during epidermal development and differentiation. Genes Dev. 1991;5:714–727. doi: 10.1101/gad.5.5.714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vassar R, Hutton ME, Fuchs E. Transgenic overexpression of transforming growth factor bypasses the need for c-Ha-ras mutations in mouse skin tumorigenesis. Mol Cell Biol. 1992;12:4643–4653. doi: 10.1128/mcb.12.10.4643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang XJ, Greenhalgh DA, Eckhardt JN, Rothnagel JA, Roop DR. Epidermal expression of transforming growth factor-alpha in transgenic mice: induction of spontaneous and 12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol-13-acetate-induced papillomas via a mechanism independent of Ha-ras activation or overexpression. Mol Carcinog. 1994;10:15–22. doi: 10.1002/mc.2940100104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dlugosz AA, Hansen L, Cheng C, et al. Targeted disruption of the epidermal growth factor receptor impairs growth of squamous papillomas expressing the v-ras(Ha) oncogene but does not block in vitro keratinocyte responses to oncogenic ras. Cancer Res. 1997;57:3180–3188. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hansen LA, Woodson RL, Holbus S, Strain K, Lo YC, Yuspa SH. The epidermal growth factor receptor is required to maintain the proliferative population in the basal compartment of epidermal tumors. Cancer Res. 2000;60:3328–3332. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.El-Abaseri TB, Putta S, Hansen LA. Ultraviolet irradiation induces keratinocyte proliferation and epidermal hyperplasia through the activation of the epidermal growth factor receptor. Carcinogenesis. 2006;27:225–231. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgi220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.El-Abaseri TB, Hansen LA. EGFR Activation and Ultraviolet Light-Induced Skin Carcinogenesis. J Biomed Biotechnol. 2007;2007:97939. doi: 10.1155/2007/97939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Xian W, Rosenberg MP, DiGiovanni J. Activation of erbB2 and c-src in phorbol ester-treated mouse epidermis: possible role in mouse skin tumor promotion. Oncogene. 1997;14:1435–1444. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1200980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bol D, Kiguchi K, Beltran L, et al. Severe follicular hyperplasia and spontaneous papilloma formation in transgenic mice expressing the neu oncogene under the control of the bovine keratin 5 promoter. Mol Carcinog. 1998;1:2–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Xie W, Wu X, Chow LT, Chin E, Paterson AJ, Kudlow JE. Targeted expression of activated erbB-2 to the epidermis of transgenic mice elicits striking developmental abnormalities in the epidermis and hair follicles. Cell Growth Differ. 1998;9:313–325. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Xie W, Chow LT, Paterson AJ, Chin E, Kudlow JE. Conditional expression of the ErbB2 oncogene elicits reversible hyperplasia in stratified epithelia and up-regulation of TGFalpha expression in transgenic mice. Oncogene. 1999;18:3593–3607. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kiguchi K, Bol D, Carbajal S, et al. Constitutive expression of erbB2 in epidermis of transgenic mice results in epidermal hyperproliferation and spontaneous skin tumor development. Oncogene. 2000;19:4243–4254. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Madson JG, Lynch DT, Tinkum KL, Putta SK, Hansen LA. Erbb2 regulates inflammation and proliferation in the skin after ultraviolet irradiation. Am J Pathol. 2006;169:1402–1414. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2006.060082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Madson JG, Hansen LA. Multiple mechanisms of Erbb2 action after ultraviolet irradiation of the skin. Mol Carcinog. 2007;46:624–628. doi: 10.1002/mc.20335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Madson JG, Lynch DT, Svoboda J, et al. Erbb2 suppresses DNA damage-induced checkpoint activation and UV-induced mouse skin tumorigenesis. Am J Pathol. 2009;174:2357–2366. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2009.080638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Eldridge SR, Tilbury LF, Goldsworthy TL, Butterworth BE. Measurement of chemically induced cell proliferation in rodent liver and kidney: a comparison of 5-bromo-2'-deoxyuridine and [3H]thymidine administered by injection or osmotic pump. Carcinogenesis. 1990;11:2245–2251. doi: 10.1093/carcin/11.12.2245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Naito M, Naito Y, DiGiovanni J. Comparison of the histological changes in the skin of DBA/2 and C57BL/6 mice following exposure to various promoting agents. Carcinogenesis. 1987;8:1807–1815. doi: 10.1093/carcin/8.12.1807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bol DK, Kiguchi K, Gimenez-Conti I, Rupp T, DiGiovanni J. Overexpression of insulin-like growth factor-1 induces hyperplasia, dermal abnormalities, and spontaneous tumor formation in transgenic mice. Oncogene. 1997;14:1725–1734. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1201011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Riggs PK, Angel JM, Abel EL, DiGiovanni J. Differential gene expression in epidermis of mice sensitive and resistant to phorbol ester skin tumor promotion. Mol Carcinog. 2005;44:122–136. doi: 10.1002/mc.20127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nanney LB, Magid M, Stoscheck CM, King LE., Jr Comparison of epidermal growth factor binding and receptor distribution in normal human epidermis and epidermal appendages. J Invest Dermatol. 1984;83:385–393. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12264708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gullick WJ, Hughes CM, Mellon K, Neal DE, Lemoine NR. Immunohistochemical detection of the epidermal growth factor receptor in paraffin-embedded human tissues. J Pathol. 1991;164:285–289. doi: 10.1002/path.1711640403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bauknecht T, Gross G, Hagedorn M. Epidermal growth factor receptors in different skin tumors. Dermatologica. 1985;171:16–20. doi: 10.1159/000249380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Liu B, Zhang H, Li S, Chen W, Li R. The expression of c-erbB-1 and c-erbB-2 oncogenes in basal cell carcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma of skin. Chin Med Sci J. 1996;11:106–109. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Krahn G, Leiter U, Kaskel P, et al. Coexpression patterns of EGFR, HER2, HER3 and HER4 in non-melanoma skin cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2001;37:251–259. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(00)00364-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rittie L, Kansra S, Stoll SW, et al. Differential ErbB1 signaling in squamous cell versus basal cell carcinoma of the skin. Am J Pathol. 2007;170:2089–2099. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2007.060537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lavrijsen AP, Tieben LM, Ponec M, van der Schroeff JG, van Muijen GN. Expression of EGF receptor, involucrin, and cytokeratins in basal cell carcinomas and squamous cell carcinomas of the skin. Arch Dermatol Res. 1989;281:83–88. doi: 10.1007/BF00426583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yamamoto T, Kamata N, Kawano H, et al. High incidence of amplification of the epidermal growth factor receptor gene in human squamous carcinoma cell lines. Cancer Res. 1986;46:414–416. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Iordanov MS, Choi RJ, Ryabinina OP, Dinh TH, Bright RK, Magun BE. The UV (Ribotoxic) stress response of human keratinocytes involves the unexpected uncoupling of the Ras-extracellular signal-regulated kinase signaling cascade from the activated epidermal growth factor receptor. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:5380–5394. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.15.5380-5394.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fisher GJ, Talwar HS, Lin J, et al. Retinoic acid inhibits induction of c-Jun protein by ultraviolet radiation that occurs subsequent to activation of mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways in human skin in vivo. J Clin Invest. 1998;101:1432–1440. doi: 10.1172/JCI2153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Katiyar SK. A single physiologic dose of ultraviolet light exposure to human skin in vivo induces phosphorylation of epidermal growth factor receptor. Int J Oncol. 2001;19:459–464. doi: 10.3892/ijo.19.3.459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wan YS, Wang ZQ, Shao Y, Voorhees JJ, Fisher GJ. Ultraviolet irradiation activates PI 3-kinase/AKT survival pathway via EGF receptors in human skin in vivo. Int J Oncol. 2001;18:461–466. doi: 10.3892/ijo.18.3.461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Moasser MM. The oncogene HER2: its signaling and transforming functions and its role in human cancer pathogenesis. Oncogene. 2007;26:6469–6487. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lebeau S, Masouye I, Berti M, et al. Comparative analysis of the expression of ERBIN and Erb-B2 in normal human skin and cutaneous carcinomas. Br J Dermatol. 2005;152:1248–1255. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2005.06687.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Stoll SW, Kansra S, Peshick S, et al. Differential utilization and localization of ErbB receptor tyrosine kinases in skin compared to normal and malignant keratinocytes. Neoplasia. 2001;3:339–350. doi: 10.1038/sj.neo.7900170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Piepkorn M, Predd H, Underwood R, Cook P. Proliferation-differentiation relationships in the expression of heparin-binding epidermal growth factor-related factors and erbB receptors by normal and psoriatic human keratinocytes. Arch Dermatol Res. 2003;295:93–101. doi: 10.1007/s00403-003-0391-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Maguire HC, Jr, Jaworsky C, Cohen JA, Hellman M, Weiner DB, Greene MI. Distribution of neu (c-erbB-2) protein in human skin. J Invest Dermatol. 1989;92:786–790. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12696796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ahmed NU, Ueda M, Ichihashi M. Increased level of c-erbB-2/neu/HER-2 protein in cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. Br J Dermatol. 1997;136:908–912. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rusnak DW, Affleck K, Cockerill SG, et al. The characterization of novel, dual ErbB-2/EGFR, tyrosine kinase inhibitors: potential therapy for cancer. Cancer Res. 2001;61:7196–7203. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kiguchi K, Ruffino L, Kawamoto T, Ajiki T, Digiovanni J. Chemopreventive and therapeutic efficacy of orally active tyrosine kinase inhibitors in a transgenic mouse model of gallbladder carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:5572–5580. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-2603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Xian W, Kiguchi K, Imamoto A, Rupp T, Zilberstein A, DiGiovanni J. Activation of the epidermal growth factor receptor by skin tumor promoters and in skin tumors from SENCAR mice. Cell Growth Differ. 1995;6:1447–1455. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Murali R, Brennan PJ, Kieber-Emmons T, Greene MI. Structural analysis of p185c-neu and epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinases: oligomerization of kinase domains. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:6252–6257. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.13.6252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Qian X, LeVea CM, Freeman JK, Dougall WC, Greene MI. Heterodimerization of epidermal growth factor receptor and wild-type or kinase-deficient Neu: a mechanism of interreceptor kinase activation and transphosphorylation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:1500–1504. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.4.1500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lenferink AE, Pinkas-Kramarski R, van de Poll ML, et al. Differential endocytic routing of homo- and hetero-dimeric ErbB tyrosine kinases confers signaling superiority to receptor heterodimers. Embo J. 1998;17:3385–3397. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.12.3385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]