Abstract

Objective

To describe and evaluate participant recruitment for a research study conducted in primary care offices.

Study Design and Setting

Nine recruiters administered a written survey to 1,485 primary care patients (from 25 practices) during baseline and one year follow-up of a quality improvement study aimed at increasing colorectal cancer (CRC) screening. Prior to recruitment, recruiters attended training sessions during which they received tools and information designed to facilitate successful recruitment. Quantitative and qualitative recruitment data were analyzed to assess and describe recruitment efforts.

Results

The overall practice level recruitment rate was 72.7% (range: 56.3% – 91.4%). Practice characteristics did not affect the recruitment rate. Recruitment rate differed significantly between recruiters (p=0.0007), as did non-participants’ reason for refusal (p<0.0001). Anticipated barriers to recruitment (older age of sampled population, lack of incentives, and discomfort discussing CRC) did not occur. Two key strategies facilitated recruitment: 1) recruiter flexibility and 2) building rapport with participants.

Conclusion

Recruiters may be more effective if they are able to adapt to participants’ needs and successfully build rapport with potential participants. The likelihood of recruitment success may be increased by anticipating potential recruitment barriers and providing training that minimizes the inherent variation that exists among recruiters.

Introduction

Adequate and timely participant recruitment can determine a research study’s success. Enrolling a targeted sample size in a specified time period helps ensure sufficient statistical power(1, 2) and keeps study operations within budget, time, and personnel constraints(3, 4). In-person recruitment of participants is one technique that has been shown to be both successful(5–8) and cost-effective(9–11) in multiple study types; however, researchers rarely report the strategies used to facilitate successful in-person recruitment.

Several attributes of successful recruiters have been identified including flexibility in recruitment techniques(5, 7, 11) and dedication to the research(11, 12). In addition, study participants identify competent, personable and experienced recruiters as positively influencing their decision to participate in research(8, 13). While these findings point to the importance of adequately training recruiters, very little documentation exists on the actual training methods researchers use to do this(14, 15).

This paper describes participant recruitment for Project SCOPE (Supporting Colorectal Cancer Outcomes through Participatory Enhancements). Barriers to recruitment success were anticipated based on the older age of the sampled population, the sensitive nature of colorectal cancer (CRC), and the lack of incentives. In this article, we report on recruitment outcomes and offer strategies to aid other researchers conducting in-person recruitment. Qualitative examples of recruiters’ experiences are used to provide concrete and practical information that is often left out of scholarly work pertaining to participant recruitment.

Methods

Description of SCOPE Study

Project SCOPE was a five-year quality improvement intervention study funded by the National Cancer Institute. SCOPE used a multimethod assessment process(16) to inform a facilitated team-building intervention(17) that aimed to increase CRC screening rates in primary care practices. A convenience sample of 25 family and internal medicine practices were recruited from the New Jersey Family Medicine Research Network. Each participating practice provided written, informed consent, as did all participants. The University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey-Robert Wood Johnson Medical School Institutional Review Board approved this study.

Data Collection

Baseline and one year follow-up data were collected during January 2006 through May 2008. Data were collected in 25 practices at baseline and in 23 at one year follow-up (due to closure of 2 practices). Recruiters approached consecutive patients in the waiting rooms of each practice in an effort to recruit 30 participants who consented to completing a survey and having their medical record reviewed. Occasionally, 1–2 additional participants were recruited to account for drop outs or missing records. Eligible patients were 50 or older, had at least one prior visit in the practice, and could read/write in English or Spanish. Participants completed a written survey that included demographics, risk factors, cancer screening dates, health care seeking behaviors, self-rated health, and satisfaction with care. Incentives were not provided to participants.

Participant Recruitment

Nine recruiters enrolled participants over the course of the study; 3 during baseline and 6 during one year follow-up. All but one of these recruiters was female and most fell into the 20–40 age range. The educational backgrounds of the recruiters varied and included high school graduates, MPH students and graduates, a registered nurse, and a PhD in sociology. The racial backgrounds of recruiters also varied and included white, Hispanic, Asian Indian, and African American. Only one recruiter had previous experience enrolling research study participants, but others had related experience including working in a primary care setting and approaching individuals for market research purposes. Two of the recruiters were bilingual and were responsible for recruitment at practices with large Spanish-speaking patient populations. Non-bilingual recruiters recruited only English-speaking participants.

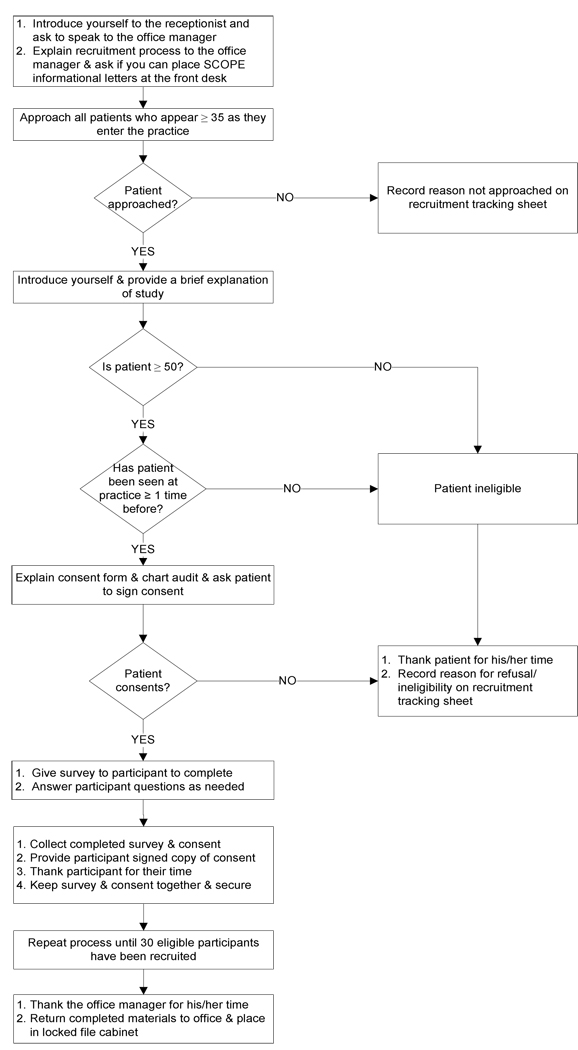

Recruiters followed a standard recruitment protocol designed by the research team (Figure 1). The length of time recruiters spent at each practice ranged from 3 to 18 days and varied based on the practice’s schedule and patient volume.

Figure 1.

Participant Recruitment Protocol for Supporting Colorectal Outcomes through Participatory Enhancements (SCOPE)

The following details a typical interaction between a recruiter and a patient:

Context: Hilltop practice has a small waiting room, with approximately 15 chairs. An elderly woman enters the practice and approaches the front desk window. The receptionist speaks with the patient and then asks her to have a seat. The recruiter gathers her clipboard, survey, and pen and approaches the patient, whose age is unknown.

Recruiter: Good morning, may I interrupt you?

Patient: Sure.

Recruiter: My name is Emma and I'm from the University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey (pointing to her identification badge). We are currently working with your practice to help improve cancer screening rates. To do this, we are asking patients who have been seen at this office before and who are at least 50 years old if they'd be willing to fill out a brief survey. Are you at least 50 years old?

Patient: Yes.

Recruiter: Have you been seen by Dr. Roberts before?

Patient: Yes, I’ve been coming here for years.

Recruiter: That means you would be eligible to complete the survey if you’re interested. It takes about 15 minutes so you can complete it while you wait. We keep all information confidential and won’t contact you in the future. After you complete the survey, a nurse that I work with will come in and review parts of your medical record that pertain to cancer screening. Would you be willing to fill out the survey today?

If the patient consented, the recruiter would then review the consent form and assist with the survey if needed. If the patient refused, recruiters would respond positively (e.g.,): "Thank you anyways – have a wonderful day" and would then ask for and record the patient’s reason for refusal. Recruiters sometimes failed to approach potentially eligible participants because the patient was called into the exam room immediately or because the recruiter was busy assisting another participant.

Analysis of Recruitment Data

Recruitment rates represent the percentage of patients approached that consented to participate. Analyses of variance were used to evaluate the effect of recruiter and practice characteristics on recruitment rates. A chi-square test was conducted to evaluate the difference in non-participants’ refusal reasons between recruiters. Qualitative data on recruiters’ experiences were collected during an exploratory debriefing session that included four recruiters who were working full-time on the project at the time of the session. During the session, recruiters discussed the challenges they faced during recruitment and techniques used to facilitate recruitment and notes were taken by one of the authors.

Data Quality

Recruiter Training

Prior to beginning recruitment, recruiters attended a day-long, in-house training session and also shadowed more experienced recruiters. Descriptions of the training modules are provided below:

1. Project overview

A history of SCOPE’s development and an overview of the project’s structure, timeline, and primary goals were given. This presentation provided context for the recruiters and prepared them to knowledgeably answer patient and practice member questions. National and local CRC mortality and screening statistics were presented to provide background on the study’s significance.

2. Data collection

Experienced recruiters reviewed the participant survey with the new recruiters and explained how to answer questions commonly raised by participants. Articles that defined the CRC screening tests and other medical terms used in the survey(18, 19) were discussed, as were strategies for tactfully explaining these tests to participants. A document covering frequently asked questions about recruitment and appropriate responses (developed based on earlier experiences) was also discussed (Appendix 1). Finally, tips for being an effective recruiter were presented including the importance of a professional appearance and friendly demeanor.

3. Subject consent

Experienced recruiters reviewed methods for obtaining informed consent and the key points of the consent form including: 1) participation is voluntary, 2) there are no foreseen risks to participation, 3) participants have the right to withdraw at any time, and 4) all participant information is kept confidential. New recruiters were instructed that family members or caretakers could not provide proxy consent for participants. Making sure each participant understood that providing consent included agreeing to both the survey and a one-time medical record audit was also emphasized.

4. Confidentiality

This module covered the importance of participant confidentiality and prepared recruiters to evaluate and respond to situations in which confidentiality might be compromised. New recruiters were instructed to keep completed surveys secure and maintain possession of completed materials at all times (e.g., when taking a break or leaving the practice for lunch). Situations requiring recruiters to judge whether privacy could be maintained were discussed including introducing the study to a hearing impaired patient or reading the survey to a visually impaired patient in a crowded waiting room. New recruiters were given examples of the appropriate way to respond in these situations and were instructed to always maintain participant privacy, even if that meant refusing an individual that was otherwise willing to participate.

5. Simulated recruitment exercises

New recruiters participated in role-playing exercises to become more comfortable with approaching patients. Experienced recruiters provided a demonstration of a typical patient interaction that focused on assessing eligibility, giving a brief introduction of the study, and obtaining written consent. Although a standardized script was used in this demonstration, recruiters were encouraged to adapt the script to different situations if necessary. To do this, recruiters participated in role-playing scenarios that involved unexpected situations, such as encountering individuals who were very emotional due to a recent cancer diagnosis or were offended that the recruiter assumed they were over 50. Recruiters were challenged to quickly think of ways to respond appropriately and professionally, and were given on-the-spot, constructive feedback.

6. Shadowing

In addition to the in-house training, new recruiters also spent 2–3 days observing an experienced recruiter in real-life interactions with patients. During this time, the new recruiters approached patients on their own while under the supervision of the experienced recruiter. This proved to be an especially important part of the training as it helped new recruiters gain confidence approaching patients and provided learning opportunities to improve their recruitment techniques.

Continuous Quality Control

Although recruiters worked independently in the practices, project management took several steps to monitor recruitment and help recruiters problem solve while in the field. Recruiters were instructed to call if there was a question they couldn’t answer or if they faced a situation in which they were uncertain how to proceed. This helped ensure that recruiters followed the standardized recruitment protocol, even when faced with unique challenges. Project management also met regularly with recruiters to give them opportunities to discuss issues arising from their work in the field and to share their experiences. These meetings helped minimize recruiter isolation and ensured that situations were being handled similarly by all recruiters.

Results

Practice Characteristics and Overall Recruitment Outcomes

Most practices were physician owned, family medicine practices located in suburban areas. Over half of the patients at 49% of the practices were privately insured and only one practice served a patient population that was greater than 75% uninsured. The recruitment rate ranged from 56.3% to 91.4% among practices (median=75.6, Q1=70.0, Q3=79.5). There was no association between practice characteristics and recruitment rates (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of Practices in Supporting Colorectal Outcomes through Participatory Enhancements (SCOPE), New Jersey, 2006 – 2008

| Practice Characteristics | Total N | % | Average recruitment rate (%)* |

P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total sample | 25 | 100 | ||

| Type of practice | ||||

| Family medicine | 20 | 72.0 | 75.5 | |

| Internal medicine | 3 | 20.0 | 79.2 | |

| Family and internal medicine | 2 | 8.0 | 73.7 | 0.7641 |

| Number of physicians per practice | ||||

| 1 | 6 | 24.0 | 79.8 | |

| 2–5 | 12 | 48.0 | 74.6 | |

| ≥ 6 | 7 | 28.0 | 75.2 | 0.5275 |

| Mid-level providers | ||||

| None | 13 | 52.0 | 75.0 | |

| Nurse practitioners | 5 | 20.0 | 80.4 | |

| Physician assistants | 4 | 16.0 | 79.9 | |

| Both nurse practitioner and physician assistant | 3 | 12.0 | 67.0 | 0.3483 |

| Ownership type | ||||

| Physician | 19 | 76.0 | 75.4 | |

| Hospital health system | 3 | 12.0 | 69.0 | |

| University | 2 | 8.0 | 90.5 | |

| Other | 1 | 4.0 | 76.7 | 0.0980 |

|

Insurance type of patients seen at practice Private |

||||

| < 50% | 7 | 28.0 | 75.1 | |

| 50–75% | 14 | 48.0 | 76.5 | |

| > 75% | 6 | 24.0 | 75.8 | 0.9549 |

| Medicare | ||||

| < 50% | 23 | 92.0 | 75.9 | |

| 50–75% | 2 | 8.0 | 77.0 | 0.8951 |

| Medicaid | ||||

| < 50% | 23 | 92.0 | 76.7 | |

| 50–75% | 2 | 8.0 | 67.0 | 0.1653 |

| None | ||||

| < 50% | 23 | 92.0 | 75.4 | |

| 50–75% | 1 | 4.0 | 87.6 | |

| > 75% | 1 | 4.0 | 76.7 | 0.4672 |

| Location | ||||

| Urban | 1 | 4.0 | 78.9 | |

| Suburban | 20 | 80.0 | 74.9 | |

| Rural | 4 | 16.0 | 81.9 | 0.3674 |

Average of baseline and one year follow-up recruitment rates

Participant Characteristics

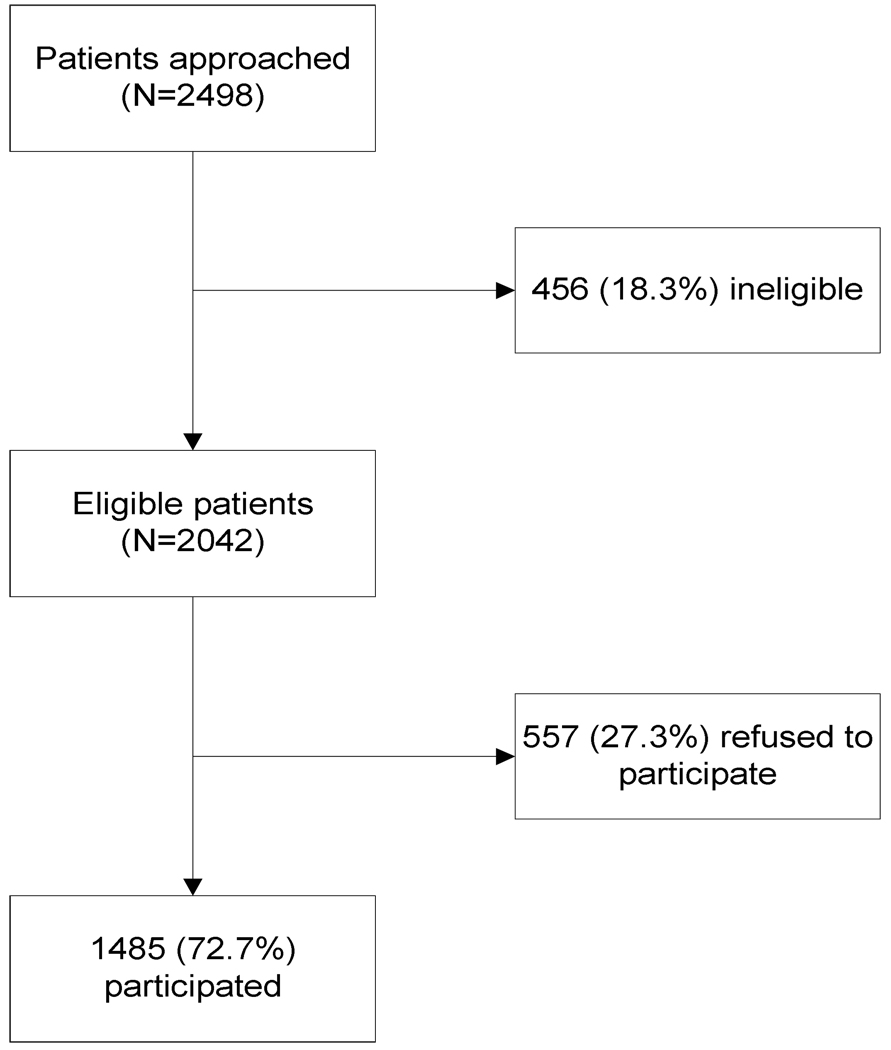

A total of 2498 patients were approached during baseline and one year follow-up. Two thousand and forty-two patients were eligible to participate and of these, 72.7% (N=1485) consented to participate (Figure 2). Participant characteristics are described in Table 2. Most participants were white, female, married, with at least a high school education (Table 2).

Figure 2.

Summary of Participant Recruitment Results in Supporting Colorectal Outcomes through Participatory Enhancements (SCOPE), New Jersey, 2006 – 2008

Table 2.

Characteristics of Participants in Supporting Colorectal Outcomes through Participatory Enhancements (SCOPE), New Jersey, 2006 – 2008

| Participant Characteristics | Total N | % |

|---|---|---|

| Total sample | 1485 | 100 |

| Age | ||

| 50–59 | 592 | 39.9 |

| 60–69 | 481 | 32.4 |

| 70 and over | 412 | 27.7 |

| Gender | ||

| Female | 882 | 59.4 |

| Male | 603 | 40.6 |

| Race* | ||

| White | 1074 | 72.8 |

| Black | 232 | 15.7 |

| Hispanic | 102 | 6.9 |

| Other | 68 | 4.6 |

| Marital status* | ||

| Married | 932 | 63.0 |

| Not married | 546 | 37.0 |

| Education level* | ||

| Less than high school | 166 | 11.3 |

| HS diploma or some college | 723 | 49.0 |

| College or graduate school degree | 586 | 39.7 |

| Insurance* | ||

| Private | 718 | 49.0 |

| Medicare | 553 | 37.7 |

| Medicaid | 62 | 4.2 |

| Other | 77 | 5.3 |

| None | 56 | 3.8 |

Numbers do not add to total due to missing data

Recruitment Outcomes between Recruiters

Average recruitment rates differed significantly among recruiters (F=4.44, p=0.0007). Overall, the main reasons patients refused to participate were lack of interest in the survey/study (28.1%) or objecting to the medical record review, signing the consent form, or completing the survey (21.0%). Other common refusal reasons included being too busy/not having enough time (15.6%) and being sick/disabled (17.2%). None of the non-participants stated that they were uncomfortable discussing CRC or that they refused because an incentive was not offered. Non-participants’ refusal reasons differed significantly among recruiters (χ2=133.5, p<0.0001), with certain recruiters being more likely to encounter patients that objected to the survey, chart audit, or consent form or were not interested in the study (Table 3).

Table 3.

Recruitment Rates and Non-participant Refusals among Recruiters in Supporting Colorectal Outcomes through Participatory Enhancements (SCOPE), New Jersey, 2006 – 2008

| Recruiter | Number of practices |

Number of refusals |

Average recruitment rate (%) |

Refusal Reason n (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Not Interested |

No time/ too busy |

Uncomfortable with chart audit, survey, consent |

Illness/ disability |

Other | ||||

| 1 | 22 | 181 | 81.7 | 42 (26.75) | 26 (16.56) | 50 (31.85) | 27 (17.20) | 12 (7.64) |

| 2 | 7 | 98 | 68.1 | 58 (61.70) | 9 (9.57) | 7 (7.45) | 12 (12.77) | 8 (8.51) |

| 3 | 5 | 67 | 71.9 | 9 (14.75) | 19 (31.15) | 7 (11.48) | 12 (19.67) | 14 (22.95) |

| 4 | 2 | 43 | 61.3 | 6 (14.63) | 3 (7.32) | 11 (26.83) | 6 (14.63) | 15 (36.59) |

| 5 | 5 | 122 | 57.0 | 25 (20.83) | 17 (14.17) | 21 (17.50) | 19 (15.83) | 38 (31.67) |

| 6 | 3 | 49 | 68.1 | 14 (32.56) | 2 (4.65) | 9 (20.93) | 11 (25.58) | 7 (16.28) |

| 7,8,9* | 3 | 43 | 71.4 | 3 (7.32) | 11 (26.83) | 12 (29.27) | 9 (21.95) | 6 (14.63) |

Recruiters 7, 8, and 9 each recruited at one practice only and are therefore collapsed into one category for analysis purposes

Strategies for Recruitment Success

During the debriefing session, recruiters identified several challenges common to their individual recruitment experiences. These included interacting with ill patients and finding alternate ways to explain the study to those who had trouble understanding. From these challenges, recruiters identified two key strategies that facilitated recruitment success: 1) flexibility and 2) building rapport.

Recruiter Flexibility

Recruiters often found it necessary to adapt the protocol to accommodate individual participants’ needs. For example, some patients were eager to participate but needed recruiters to read the questions to them because they had trouble seeing. In such cases, recruiters would attempt to take the individual to a previously-identified private area (e.g., an empty exam room). If this area was not available, recruiters would determine whether it was feasible to assist the patient without compromising confidentiality. If privacy couldn’t be guaranteed, then the recruiter explained to the patient that they wouldn't be able to participate and thanked them for their time.

Recruiters also adapted their approach to patients based on the patient’s body language and/or temperament. For example, if a patient expressed anger or that they were in a hurry while interacting with the office staff, the recruiter’s introduction would remain friendly but be quicker and more to the point. If a patient complained of not feeling well or was visibly sick, a recruiter might adopt a sympathetic tone of voice when speaking to the patient and acknowledge their illness by saying “I can see you’re not feeling well, but do you mind if I have a few moments of your time.” These small adaptations in the way recruiters approached patients helped put patients at ease and seemed to encourage them to consider participation.

Recruiters also had to adapt the recruitment script when they sensed that a potential participant did not understand the presented information. Many participants were quick to agree to the survey, but became confused about what participation entailed once they had read the consent form. Recruiters often had to explain the complicated consent form, provide a more detailed explanation of the study’s purpose, and assure the participant that their participation was limited to a one-time survey and medical record review only. Recruiters found that spending extra time with hesitant participants helped to alleviate concerns and increase their acceptance of the study.

Building Rapport

Recruiters recognized that patients may have viewed being asked to participate as a nuisance, especially if they were sick, in a hurry, or didn’t fully understand the study’s purpose. Acknowledging these circumstances with an understanding statement, a concerned look, or the provision of more information often helped to build rapport with potential participants. Small talk proved to be an effective way to engage some individuals who initiated conversations about non-study related topics such as their family, job, or current events. Participating in these conversations helped recruiters gain participants’ trust and confidence.

Participants sometimes needed reassurance that recruiters were nearby in the event that they had questions, and recruiters found that sitting near these participants and emphasizing that they were available to assist helped put them at ease. Other participants asked recruiters for additional assistance, such as entertaining their grandchildren in the waiting room so they were free to participate. Being able to accommodate a wide range of circumstances was therefore an essential skill for recruiters to possess.

Discussion

This analysis shows that comprehensive training of recruiters and effective project management (e.g., ongoing skill building opportunities with recruiters, consistent monitoring of recruitment efforts) are key to achieving a high in-person recruitment rate in research studies. Diverse training methods including didactic presentations, role-playing exercises, and shadowing of experienced personnel should be used to interest and invest recruiters in the study and prepare them to knowledgably address participant questions and unexpected situations. Through the SCOPE recruiter training, as well as the regular meetings with project management, recruiters became motivated, confident, and proficient at identifying strategies to facilitate recruitment and executing strategies to overcome potential barriers to recruitment.

Two strategies in particular were important to our recruitment success: flexibility and building rapport with participants. While flexibility has previously been identified as an attribute of successful recruitment(5, 7, 11), this article contains one of the few published accounts of in-person recruiter training methods that helped recruiters develop adaptive techniques without violating study protocol. We also present examples of the human factors associated with in-person recruitment, such as ill or emotional participants, that challenge recruiters to find creative ways to build rapport in a wide range of participant interactions. We found that having regular opportunities for recruiters to discuss their experiences led to the development of shared strategies for being flexible and building rapport.

Several barriers to recruitment were anticipated based on the older age of the participant population(5, 12), participants’ potential embarrassment discussing CRC screening tests(20, 21), and the lack of incentives(11). Our high recruitment rate suggests that the older age of the sampled population did not adversely affect recruitment. Recruiters actually found elderly patients (i.e., participants in their 70’s and 80’s) to be more receptive and talkative than other participants. Surprisingly, none of the non-participants stated they were uncomfortable discussing CRC and recruiters found that most participants did not express embarrassment even when recruiters explicitly defined the invasive screening tests. And although some patients occasionally asked “what’s in it for me?”, the lack of incentives was never given as a reason for refusal. Anticipating barriers in advance and taking steps such as training and ongoing recruitment meetings can help recruiters identify ways to overcome recruitment challenges and may help eliminate some of the common pitfalls of participant recruitment.

No matter how skilled or experienced recruiters are, variability is to be expected when a single recruiter enrolls participants at multiple sites(3, 7). We anticipated that individual recruiter rates would vary slightly across practices as the recruiter gained expertise and confidence in recruiting. However, we did not expect the large degree of variability that existed in some recruiter’s rates. For example, Recruiter 1 conducted recruitment at 22 of the 25 practices at baseline, producing recruitment rates that ranged from 61.5% to 97.0%. This large range suggests that practice factors not available for this analysis affected recruitment outcomes.

Despite our efforts to standardize the recruitment process, variability between recruiters also had an impact on recruitment outcomes. For example, recruiters 1 and 5 encountered a greater number of patients who refused because they were uncomfortable with the survey, chart audit, or consent. Possible explanations for this include a lack of clarity in these recruiters’ explanations of participation or a difference in the way the recruiters recorded the non-participants’ refusals. Variability between recruiters may also be explained by patient characteristics such as an objection to the recruiters’ appearance or mannerisms, negative views of the university(8, 22) or distrust of the medical/research community(4, 23, 24). Recruiter training exercises including role-playing and shadowing of experienced recruiters can help to minimize this variation, but it’s likely that some will still exist between recruiters. Awareness of this inherent variability can prompt researchers to devise methods to monitor and evaluate the differences among recruiters and make adjustments to recruitment methods as necessary.

Our analysis has both methodological strengths and weaknesses. Strengths include the richness of the qualitative data and the detailed explanation of recruiter training methods. Limitations include the fairly low percentage of minority participants and the relative lack of diversity among the participating practices, both of which limit our ability to generalize our results. Additionally, it is impossible to evaluate the representativeness of the participant group due to the lack of non-participant data.

Although participant recruitment remains challenging, our experience in SCOPE supports the importance of developing a standardized recruitment protocol, comprehensively training recruiters, and initiating regular recruitment meetings. Researchers are urged to publish their recruiter training methods and strategies for success so that others can learn from their experiences in a variety of recruitment scenarios.

Acknowledgements

We are indebted to all of the participants who agreed to take part in the study, as well as the clinicians and staff members of each participating practice. We thank the Family Medicine Research Network, the SCOPE research team, and all of the SCOPE recruiters, especially Contributor 1 for her contributions during the recruitment debriefing session. Finally, we thank the National Cancer Institute for funding this research.

Funding Source

This manuscript is comprised of data arising from the Supporting Colorectal Outcomes through Participatory Enhancements (SCOPE) study, which is funded by the National Cancer Institute (1R01CA112387-01).

Appendix 1

Frequently Asked Questions Document for Supporting Colorectal Outcomes through Participatory Enhancements (SCOPE) Recruiter Training

Frequently Asked Questions (from patients)

- Patient: Is there any test involved?Response(s): No, we only ask that you fill out this survey while you wait for your appointment.

- Patient: Are you going to call my home or send me emails?Response(s): No, we will not contact you at all. This is simply a one-time request for you to fill out a survey.

- Patient: Can I do the survey without signing the consent form?Response(s): No, because we are with the University, we need to have your signature on the consent form. If someone at the University needed to check to see that you agreed to fill out the survey, we would have to show them the signed consent form. Otherwise, your information from the survey is kept completely confidential and no one will be able to identify you from your information.

- Patient: Can I change my mind at any time?Response(s): Yes, there is information in the consent form (which I’ll give you a copy of) that explains what to do if you change your mind about participating.

- Patient: I can't read or write so well, can you do the questionnaire for me?Response(s): <Your response will depend on whether or not you can help them complete the survey privately.><If privacy can be assured>: I can read the consent form and questions to you. Then you can tell me your answers and I’ll mark them down.<If you cannot assure privacy>: I’m sorry but there’s not enough privacy for me to read the survey out loud to you. Thank you very much for offering to participate.

- Patient: If my husband participates, can I write the answers for him because I know everything about him?Response(s): That’s fine but he will need to be the one who signs the consent form and he needs to be able to confirm that what you’re writing down is accurate. <So if the husband is called back into the exam room, it would NOT be acceptable for the wife to complete the form on her own. >

- Patient: I didn’t have my colonoscopy (or other test) at this practice. Should I still fill this out?Response(s): Yes, it is important for us to know if you’ve had this test even if it was done elsewhere.

- Patient: I can’t remember the date of my colonoscopy (or other) test. What should I do?Response(s): That’s understandable. Please write down your best guess for this date.

- Patient: Can I take the survey into the exam room with me?Response(s): Yes, of course. You can use this clipboard to write on. I’ll be here in the waiting room so when you’re finished, please return the survey to me before you leave.

- Patient: Can I take the survey home to finish it and then mail it back to you?Response(s): No, we do require that you complete the survey here in the office and return it to me.

- Patient: Did the doctor say it was okay to fill this out?/Does the doctor know you’re doing this?Response(s): Yes, the physician(s) have given us permission to do this so that we can help the practice improve their cancer screening rates.

- Patient: I took this last time. Can I do it again?Response(s): If you took it last year, then, yes you can fill it out again for us this year. (If the patient completed the survey this year, then they would not be able to do it again).

- Patient: How will filling out this survey benefit me?Response(s): Unfortunately, we don’t give anything directly to you, but your contribution (and the other patients who are also filling out surveys here) will help your doctors know how well they are doing in making sure patients are receiving appropriate cancer screening tests. So we really hope that our work with your practice will improve the patient care around cancer screening for all patients here.

- Patient: Who will have access to my chart/medical record?Response(s): One of our research team members will review your chart on a onetime basis. No identifying information (e.g., name, address, SSN, etc) will be taken. We assign you a number and so all of your information is kept completely confidential. The information we do take from your chart (e.g., height, weight, date of any cancer screenings) is then entered in a computer file. This allows members of our research team to analyze the information from all of the patients in this practice to see how well your physicians are doing in making sure patients are receiving appropriate cancer screening tests. (You may refer the patient to page 2 of the consent form to note who else may see their information – Institutional Review Board, National Cancer Institute, etc).

- Patient: I don’t have cancer, so will I be a good candidate?Response(s): Yes, we would still like for you to participate because we want to know if patients who are eligible to receive certain cancer screening tests have received them. These tests are important tools for preventing cancer so it’s important for us to know how well they are being used for any patient.

- Patient: What if I don’t know if I’ve had a test or not?/What if I don’t know all the answers?Response(s): That’s ok. You can always ask me for help if something on the survey is unclear. If you don’t know if you’ve had a test, you can indicate that on the survey. If you can’t remember when you had a particular test, you can write your best guess.

- Patient: Why do I have to sign the consent form if this is confidential?Response(s): Keeping your health information private is very important to us and we have to follow University rules in order to do this study. One of the rules is that we must have proof that you agreed to fill out this survey for us – that’s why we need your signature on the consent form. This form is kept separate in a locked cabinet from your survey information so we don’t use your name at all.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Statements

Christina Felsen has no potential conflict of interest

Dr. Shaw has no potential conflict of interest

Dr. Ferrante has no potential conflict of interest

Lorraine Lacroix has no potential conflict of interest

Dr. Crabtree has no potential conflict of interest

References

- 1.Amthauer H, Gaglio B, Glasgow RE, Dortch W, King DK. Lessons learned: patient strategies for a type 2 diabetes intervention in a primary care setting. Diabetes Educ. 2003;29(4):673–681. doi: 10.1177/014572170302900413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ross S, Grant A, Counsell C, Gillespie W, Russell I, Prescott R. Barriers to participation in randomised controlled trials: A systematic review. J Clin Epidemiol. 1999;52(12):1143–1156. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(99)00141-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Agras WS, Bradford RH. Recruitment: An Introduction. Circulation. 1982;66 Suppl IV:IV-2–IV-5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Swanson G, Ward A. Recruiting minorities into clinical trials: toward a participant-friendly system. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1995;87:1747–1759. doi: 10.1093/jnci/87.23.1747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Harris R, Dyson E. Recruitment of frail older people to research: lessons learnt through experience. J Adv Nurs. 2001;36(5):643–651. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2001.02029.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Smith SR, Jaffe DM, Petty M, Worthy V, Banks P, Strunk RC. Recruitment into a long-term pediatric asthma study during emergency department visits. J Asthma. 2004;41(4):477–487. doi: 10.1081/jas-120033991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ory MG, Lipman PD, Karlen PL, et al. Recruitment of older participants in frailty/injury prevention studies. Prev Sci. 2002;3(1):1–22. doi: 10.1023/a:1014610325059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chang B-H, Hendricks AM, Slawsky MT, Locastro JS. Patient recruitment to a randomized clinical trial of behavioral therapy for chronic heart failure. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2004;4:8. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-4-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ellis PM. Attitudes towards and participation in randomised clinical trials in oncology: A review of the literature. Ann Oncol. 2000;11:939–945. doi: 10.1023/a:1008342222205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Margitić S, Sevick MA, Miller M, et al. Challenges faced in recruiting patients from primary care practices into a physical activity intervention trial. Prev Med. 1999;29(4):277–286. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1999.0543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Adams J, Silverman M, Musa D, Peele P. Recruiting older adults for clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1997;18:14–26. doi: 10.1016/s0197-2456(96)00132-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Petrovitch H, Byington R, Bailey G, et al. Systolic Hypertension in the Elderly Program (SHEP). Part 2: Screening and recruitment. Hypertension. 1991;17(3 Suppl):II16–II23. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.17.3_suppl.ii16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Seltzer SE, Sullivan DC, Hillman BJ, Staab EV. Factors affecting patient enrollment in radiology clinical trials: a case study of the American College of Radiology Imaging Network. Acad Radiol. 2002;9:862–869. doi: 10.1016/s1076-6332(03)80365-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Love MM, Pearce KA, Williamson MA, Barron MA, Shelton BJ. Patients, practices, and relationships: challenges and lessons learned from the Kentucky Ambulatory Network (KAN) CaRESS clinical trial. J Am Board Fam Med. 2006;19(1):75–84. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.19.1.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Glickman SW, Anstrom KJ, Lin L, et al. Challenges in enrollment of minority, pediatric, and geriatric patients in emergency and acute care clinical research. Ann Emerg Med. 2008;51(6):775–780. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2007.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Crabtree BF, Miller WL, Stange KC. Understanding practice from the ground up. J Fam Pract. 2001;50(10):881–887. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stroebel CK, McDaniel RR, Jr, Crabtree BF, Miller WL, Nutting PA, Stange KC. How complexity science can inform a reflective process for improvement in primary care practices. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2005;31(8):438–446. doi: 10.1016/s1553-7250(05)31057-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Agrawal J, Syngal S. Colon cancer screening strategies. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2005;21:59–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Klabunde CN, Frame PS, Meadow A, Jones E, Nadel M, Vernon SW. A national survey of primary care physicians' colorectal cancer screening recommendations and practices. Prev Med. 2003;36:352–362. doi: 10.1016/s0091-7435(02)00066-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bleiker EM, Menko FH, Taal BG, et al. Screening behavior of individuals at high risk for colorectal cancer. Gastroenterology. 2005;128(2):280–287. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rawl SM, Menon U, Champion VL, Foster JL, Skinner CS. Colorectal cancer screening beliefs. Cancer Pract. 2000;8(1):32–37. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-5394.2000.81006.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rojavin MA, Downs P, Shetzline MA, Chilingerian R, Cohard-Radice M. Factors motivating dyspepsia patients to enter clinical research. Contemp Clin Trials. 2006;27(2):103–111. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2005.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Corbie-Smith G, Thomas SB, St. George DMM. Distrust, race, and research. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162:2458–2463. doi: 10.1001/archinte.162.21.2458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Holcombe RF, Jacobson J, Li A, Moinpour CM. Inclusion of Black Americans in oncology clinical trials: The Louisiana State University Medical Center experience. Am J Clin Oncol. 1999;22(1):18–21. doi: 10.1097/00000421-199902000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]