Abstract

Lymphoid nodules are a normal component of the mucosa of the rectum, but little is known about their function and whether they contribute to the host immune response in malignancy. In rectal cancer specimens from patients with local (n = 18), regional (n = 12) and distant (n = 10) disease, we quantified T cell (CD3, CD25) and dendritic cell (CD1a, CD83) levels at the tumour margin as well as within tumour-associated lymphoid nodules. In normal tissue CD3+, but not CD25+, T cells are concentrated at high levels within lymphoid nodules, with significantly fewer cells found in surrounding normal mucosa (P = 0·001). Mature (CD83), but not immature (CD1a), dendritic cells in normal tissue are also found clustered almost exclusively within lymphoid nodules (P = < 0·0001). In rectal tumours, both CD3+ T cells (P = 0·004) and CD83+ dendritic cells (P = 0·0001) are also localized preferentially within tumour-associated lymphoid nodules. However, when comparing tumour specimens to normal rectal tissue, the average density of CD3+ T cells (P = 0·0005) and CD83+ dendritic cells (P = 0·0006) in tumour-associated lymphoid nodules was significantly less than that seen in lymphoid nodules in normal mucosa. Interestingly, regardless of where quantified, T cell and dendritic cell levels did not depend upon the stage of disease. Increased CD3+ T cell infiltration of tumour-associated lymphoid nodules predicted improved survival, independent of stage (P = 0·05). Other T cell (CD25) markers and different levels of CD1a+ or CD83+ dendritic cells did not predict survival. Tumour-associated lymphoid nodules, enriched in dendritic cells and T cells, may be an important site for antigen presentation and increased T cell infiltration may be a marker for improved survival.

Keywords: dendritic cell, lymphoid nodule, rectal cancer, T cell

Introduction

Cancer of the rectum accounts for one in three colorectal tumours [1,2]. The multi-modality approach to rectal malignancy with neoadjuvant radiation, surgery and adjuvant chemotherapy is designed to minimize the potentially devastating complications of regional or distant spread if tumour cells breach the lamina propria of the rectal lumen. However, despite advances in adjuvant therapy and rectal surgical techniques, 50% of patients still succumb to this disease [3,4]. This has driven efforts to develop active immunotherapy options for patients, and colorectal cancer vaccines are in various stages of development and testing [5–7].

Immune cell infiltration, postulated to be manifestation of an active tumour response, has been reported in most solid human tumours and lymphocytic infiltration of colorectal cancer has been shown to confer a survival advantage [8–12]. Dendritic cells have been shown to be a consistent presence in normal and malignant colonic tissue [13,14]. Dendritic cells may infiltrate tumours, capture tumour antigen and migrate eventually to lymphoid tissue to present the antigen to T cells. This process has been demonstrated in the colon, where dendritic cells within the epithelium and lamina propria may provoke a response or tolerize T cells to gut antigens depending upon the nature of the interaction and the cytokine milieu [12–14]. Considerable effort has been applied in developing dendritic cell-mediated tumour vaccines [5,6,12,15]. This has prompted investigators to characterize the density and function of T cells and dendritic cells in the proximity of colorectal tumours [16–20]. Infiltration of immature and mature dendritic cells in colorectal tumours was decreased relative to normal tissue in both primary and metastatic disease sites, with a trend for increased survival for patients with higher dendritic cell density at the tumour margin, but the results are not uniform [17–19]. The results of studies examining T cell infiltration of colorectal and other solid tumours are equally complex [21–29]. Increased infiltration of tumours by T cells may improve survival or predict a negative outcome depending upon the T cell subset and location. Attempts to correlate these different studies of tumour-immune cell interactions are difficult, given the use of different markers for both dendritic cells and T cells, each of which have varying phenotypes that can inhibit or stimulate an active response to tumour cells. In addition, recent reports suggest that dendritic cells and T cells in clusters were essential to promoting T cell activation at the tumour margin [20,22]. Overall, it appears that immune cell infiltration of tumour foci and dendritic–T cell cross-talk are both required to generate a clinically relevant response but the site of infiltration and the relative roles of dendritic cells and T cells remain to be elucidated.

A relatively unexplored aspect of the host immune response to colorectal cancer is in the role of tumour-associated lymphoid nodules found in the region of the tumour [26,30–34]. Lymphoid nodules have been recognized within the gastrointestinal tract since the initial report in 1926 by Dukes and Bussey [31]. These complexes comprise focused collections of lymphoid cells located throughout the bowel mucosa and submucosa that are concentrated commonly in high numbers in two prominent circumferential bands near the pectinate line and rectosigmoid junction [28,31]. The close interactions of immune cells in the form of these lymphoid nodules in proximity to an inflammatory or malignant process may govern the host immune response. In breast cancer regulatory T cells that were localized in these tumour-associated lymphoid nodules had a negative impact on patient survival [32]. However, no study has examined the dendritic cell and T cell composition within these nodules and changes in composition in the context of malignancy. Previous attempts to quantify dendritic cell and T cell infiltration in colorectal tumours have not included lymphoid nodules, and this may account for the variability in the literature with regard to immune cell infiltration of colorectal tumours and patient prognosis. Differences in patient outcomes may be a result of variations in localization of dendritic cells and T cells at the tumour interface. Thus we have examined the composition of tumour-associated lymphoid nodules in rectal cancer specimens in order to test the hypothesis that infiltration of dendritic cells and T cells in tumour-associated lymphoid nodules may infer improved patient prognosis.

Patients and methods

Patient and sample selection

Ethics review and approval was given by the Health Research Ethics Board at the University of Alberta. Research samples were selected from a cohort of patients with a primary resection for rectal cancer at the Royal Alexandra Hospital (Edmonton, Canada) between 1990 and 1994 using the Alberta Cancer Board Registry. The rectum was defined from patient records as being 12 cm or less from the anal verge or being below the peritoneal reflection. In those patients followed for at least 10 years, a random sampling of 60 tissue samples was completed after grouping the specimens into the stage of disease. None of the patients had neoadjuvant radiation therapy and each specimen was coded by number before being sent for staining and analysis. Twenty of the samples were taken and used for a screen of the antibodies and development of a counting protocol within tumours and lymphoid nodules. The remaining 40 specimens were randomized for the staining protocol based on previous studies quantifying immune cell infiltration of tumours, and using α = 0·05 and β-error at 20% [15–18]. Local disease is defined as stages I and II, regional disease as stage III and metastatic disease as stage IV.

Immunohistochemistry

Details of our antigen retrieval and immunostaining have been reported previously [35]. Briefly, formalin-fixed paraffin sections of tumour and normal tissue, 4-µm thick, were used. Primary antibodies included those reactive with CD1a and CD3 (Ventana Medical Systems, Tucson, AZ, USA), CD83 (1:20; Novocastra, Newcastle upon Tyne, UK), CD25 (1:400, Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA) and human leucocyte antigen D-related (HLA-DR) (1 : 40; Novocastra). The appropriate dilutions for each of the markers were developed based on testing from the 20 initial control samples. For CD1a, CD3, CD25 and CD83, antigen retrieval was completed in citrate buffer (pH 6·0) in a pressure cooker at 100°C for 10 min. For HLA-DR, antigen retrieval was completed in Tris/ethylenediamine tetraacetic acid (EDTA) (pH 9·9).

Microscopic evaluation of immune cell infiltration

The microscopic analysis on the randomized samples was completed by two independent observers. Haemoxylin and eosin-stained sections were used to confirm histology and the proper site for sampling. Areas of necrosis, oedema or sclerosis were avoided systematically.

On the Zeiss microscope with an 20× objective and 10× eyepiece an ocular grid was used at a 200× magnification comprising a high-power field (hpf) area of 0·16 mm2 to quantify CD1a, CD3, CD83, CD25 and HLA-DR positive cells within the tumour-associated lymphoid nodules and at the tumour margin as classified by morphometric analysis. For each slide 25 random, non-overlapping hpf per tumour section were analysed and the mean value per mm2 was calculated. For each sample neighbouring normal tissue sections were stained for dendritic cell and T cell infiltration as an internal control.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was conducted in the Biostatistics group at the W. W. Cross Cancer Institute. The spss software package (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA) was used to examine disease-free survival (DFS) data using Kaplan–Meier survival estimation, and the log-rank test was used for comparison of the survival curves. Statistical analyses between groups were performed using the χ2-square test for comparing proportions. Correlations were evaluated using Spearman's rank-correlation test. P < 0·05 was considered significant. The independent-sample t-test was used to compare the mean immune cell densities at the different sites in the normal and diseased mucosa. The effect of immune cell density on patient survival was evaluated with a proportional hazards regression model and with the log-rank test. All statistical tests were performed at a significance level of 5% and were two-sided.

Results

Patient and tumour characteristics

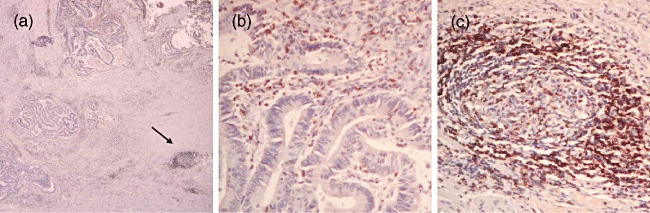

The clinicopathological parameters of the rectal cancer patients with local, regional and distant involvement are given in Table 1. A representative slide of rectal carcinoma stained with the permissive immune cell marker HLA-DR is shown at low power (Fig. 1a) and high power with sections of tumour margin (Fig. 1b) and tumour-associated lymphoid nodules (Fig. 1c). The tumour-associated lymphoid nodules and tumour margin demonstrated consistent staining for T cell (CD3, CD25), dendritic cell (CD1a, CD83) and HLA-DR markers. Tumour-associated lymphoid nodules were present in each of the rectal cancer specimens, the size varying from a minimum of 0·11 mm2 to 0·98 mm2. The relative density of lymphoid nodules, which averaged 1·7/cm2, did not vary with patient age, sex or stage of tumour.

Table 1.

Patient demographics.

| n | |

|---|---|

| Male (female) | 23 (17) |

| Mean age (years) | 64 ± 8·4 |

| Local disease (stages I/II) | 18 |

| Regional disease (stage III) | 12 |

| Metastatic disease (stage IV) | 10 |

Fig. 1.

Representative rectal cancer specimen stained with human leucocyte antigen D-related (HLA-DR): (a) at low power (40×) demonstrating tumour margin and stroma with a tumour-associated lymphoid nodule (arrow). Section (b) represents the tumour margin at 200× magnification. Section (c) represents a lymphoid nodule at 200× magnification.

Dendritic cell and T cell infiltration of normal mucosa and rectal tumours

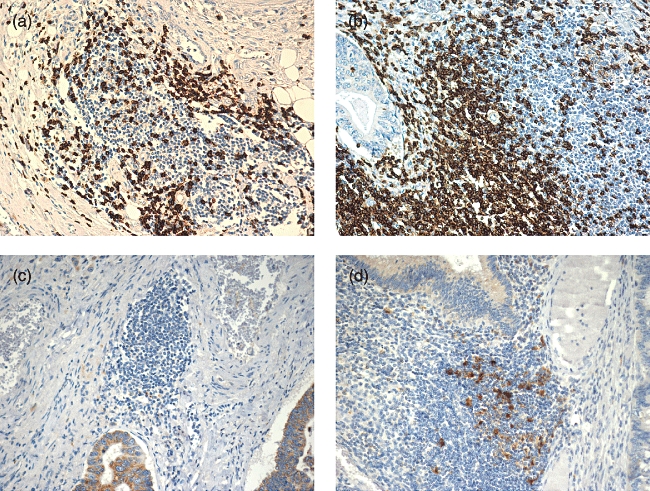

Levels of CD3+ and CD25+ T cells and CD1a+ (immature) and CD83+ (mature) dendritic cells were examined in normal rectal mucosa in isolation as well as within lymphoid nodules. Lymphoid nodules exhibited a CD3+ T cell density nearly three times higher than the isolated, scattered cells in surrounding mucosa, as shown in Table 2. For CD83+ dendritic cells the density in lymphoid nodules was more than 18× that seen in surrounding mucosa (Table 2). Conversely, CD25+ T cells demonstrated no preferential localization in lymphoid nodules and CD1a+ cell density was very low in all the sections examined. The clustering of CD3+ T cells and CD83+ dendritic cells in lymphoid nodules has not been characterized previously. The levels of dendritic cells and T cells found in lymphoid nodules and surrounding mucosa in normal tissue were then compared to tumour-associated lymphoid nodules and tumour margins (all stages). Shown in Fig. 2 are representative tumour-associated lymphoid nodules exhibiting low and high levels of infiltrating CD3+ T cells and CD83+ dendritic cells. When dendritic cell and T cell levels in tumour-associated lymphoid nodules were compared to lymphoid nodules in normal tissue, there was a significant depletion of both CD3+ T cells (P = 0·0005) as well as CD83+ dendritic cells (P = 0·0006) in tumour-associated lymphoid nodules (Table 2). However, at the tumour margin, the level of infiltration of CD3+ T cells and CD83+ dendritic cells was very similar to that found in normal mucosa (P = 0·82 and P = 0·62, respectively) (Table 2). No other marker demonstrated any difference between the pooled specimens comparing normal tissue to tumour specimens.

Table 2.

Overall dendritic cell and T cell density.

| Normal mucosa |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Lymphoid nodules |

Mucosa |

||

| Mean (s.d.) cells/hpf | P | ||

| HLA-DR+ | 73(48) | 39(41) | 0·0002 |

| CD1a+ | 1·5(3) | 1·6(5) | n.s. |

| CD3+ | 74(42)* | 29(18) | 0·0001 |

| CD25+ | 14(13) | 11(11) | n.s. |

| CD83+ | 11(7)† | 0·6(0·8) | 0·0001 |

| Rectal tumours |

|||

| Lymphoid nodules |

Tumour margin |

||

| Mean(s.d.) cells/hpf | P | ||

| HLA-DR+ | 52(37) | 28(26) | 0·001 |

| CD1a+ | 1·0(4) | 1·3(6) | n.s. |

| CD3+ | 46(24)* | 30(22) | 0·004 |

| CD25+ | 12(11) | 9·4(10) | n.s. |

| CD83+ | 5·9(5·3)† | 0·7(1) | 0·0001 |

P = 0·0005

P = 0·0006. HLA-DR, human leucocyte antigen D-related; hpf, high-power field; n.s., not significant; s.d., standard deviation.

Fig. 2.

Representative tumour-associated lymphoid nodules demonstrating (a) low and (b) high levels of CD3+ T cell infiltration. Low (c) and high (d) levels of CD83+ dendritic cell infiltration are also shown. All figures at 200× magnification.

Infiltration of rectal tumours by stage

The levels of CD3+ and CD25+ T cells, HLA-DR+ as well as CD1a+ and CD83+ dendritic cells in tumour-associated lymphoid nodules was examined as a function of stage of rectal cancer (Table 3). HLA-DR is a permissive marker for T cells, dendritic cells as well as other immune cells such as macrophages. Examination of this surrogate for overall immune cell infiltration of the tumour margin revealed that the level of HLA-DR+ cells does not vary with the stage of disease (Table 3). Moreover, none of the staining for markers of T cells or dendritic cells in lymphoid nodules varied with the extent of disease. Comparing samples with local (stages I/II) and distant disease (stage IV) also did not reveal any significant differences.

Table 3.

T cell and dendritic cell levels in tumour-associated lymphoid nodules as a function of stage of disease.

| Local |

Regional |

Metastatic |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (s.d.) cells/hpf | P | |||

| HLA-DR+ | 52 (33) | 59 (45) | 42 (33) | n.s. |

| CD1a+ | 1·5 (5) | 0·4 (3) | 0·8 (3) | n.s. |

| CD3+ | 44 (25) | 47 (16) | 46 (35) | n.s. |

| CD25+ | 11 (10) | 14 (16) | 11 (7) | n.s. |

| CD83+ | 5·3 (3·8) | 7·2 (5·5) | 5·7 (6·0) | n.s. |

HLA-DR, human leucocyte antigen D-related; hpf, high-power field; n.s., not significant; s.d., standard deviation.

The infiltration of all markers infiltrating into the margin of rectal tumours was also examined as a function of stage of disease, as shown in Table 4. Note that, overall, there are significantly lower levels of HLA-DR+, CD3+ and CD83+ cells found at the tumour margin as opposed to tumour-associated lymphoid nodules. However, none of the markers for T cell or mature dendritic cells varied as a function of stage of disease. When the stages were grouped into local (stages I/II) or metastatic disease (stage IV) and compared, no significant differences were found for any cell type. Lastly, it is clear that the average density of CD25+ T cells is much less than that seen for CD3+ T cells in either tumour-associated lymphoid nodules (P < 0·0001) or at the tumour margin (P < 0·0001) (see Table 2).

Table 4.

T cell and dendritic cell levels at tumour margin as a function of stage of disease.

| Local |

Regional |

Metastatic |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (s.d.) cells/hpf | P | |||

| HLA-DR+ | 30 (26) | 25 (25) | 26 (28) | n.s. |

| CD1a+ | 1·2 (5) | 1·6 (6) | 1·1 (8) | n.s. |

| CD3+ | 35 (23) | 36 (21) | 21 (20) | n.s. |

| CD25+ | 8 (9) | 15 (13) | 5 (4) | n.s. |

| CD83+ | 0·4 (0·3) | 1·2 (1·6) | 0·5 (0·6) | n.s. |

HLA-DR, human leucocyte antigen D-related; hpf, high-power field; n.s., not significant; s.d., standard deviation.

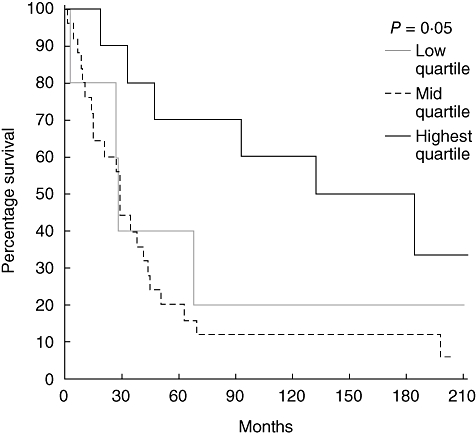

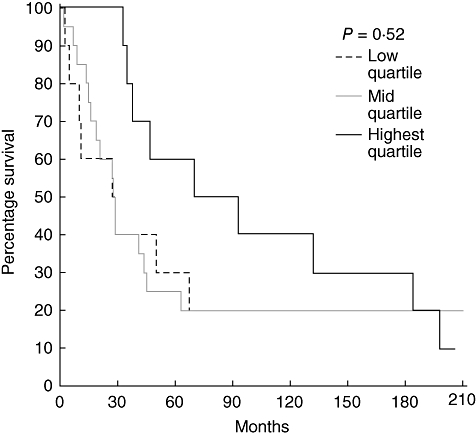

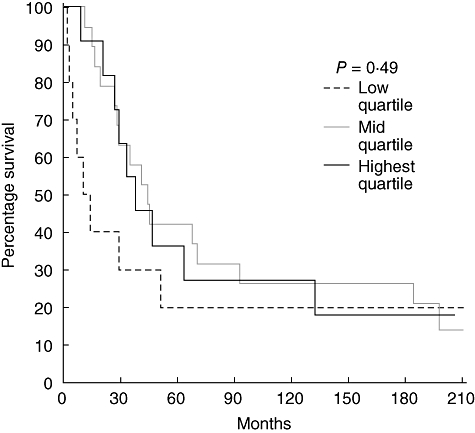

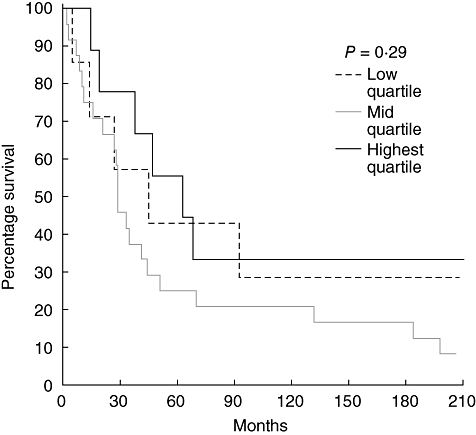

Infiltration and patient prognosis

To determine whether varying T cell or dendritic cell levels in tumour-associated lymphoid nodules or the tumour margin influenced prognosis, survival curves were examined. For each marker we examined quartiles, comparing lowest quartile to the middle 50% and highest quartile. We found that increasing CD3+ T cell levels in tumour-associated lymphoid nodules did predict survival (P = 0·05) independently of tumour stage (Fig. 3). However, the density of CD3+ cells at the tumour margin did not predict survival, as shown in Fig. 4. The levels of CD83+ dendritic cells in tumour-associated lymphoid nodules did not predict survival despite the fact that the highest quartile exhibited cell densities nearly an order of magnitude greater than the lowest quartile (Fig. 5). CD83+ dendritic cell levels at the tumour margin also did not predict survival (Fig. 6). Assessment of other markers (HLA-DR, CD25, CD1a) also revealed no relationships between cell density and survival, whether quantified at the tumour margin or within lymphoid nodules. Finally, when patients with local disease (stages I/II) or distant disease (stages III/IV) were examined for survival based on CD3+ or CD83+ cell density, no correlation was identified.

Fig. 3.

Survival curves of patients with rectal cancer (all stages) comparing the CD3+ cell density in tumour-associated lymphoid nodules. The highest quartile is compared to the middle two quartiles and the lowest quartile.

Fig. 4.

Survival curves of patients with rectal cancer (all stages) comparing the CD3+ cell density at the tumour margin. The highest quartile is compared to the middle two quartiles and the lowest quartile.

Fig. 5.

Survival curves of patients with rectal cancer (all stages) comparing the CD83+ cell density in tumour-associated lymphoid nodules. The highest quartile is compared to the middle two quartiles and the lowest quartile.

Fig. 6.

Survival curves of patients with rectal cancer (all stages) comparing the CD83+ cell density at the tumour margin. The highest quartile is compared to the middle two quartiles and the lowest quartile.

Discussion

We have demonstrated for the first time that lymphoid nodules in the rectum are comprised of high levels of CD3+ T cells and CD83+ dendritic cells. The concentration of CD83+ mature dendritic cells and CD3+ T cells in these nodules, much higher than the surrounding mucosa, may drive an active, specific response to malignancy. This may improve patient prognosis. It is also clear that, in the region of the tumour, there is a significant depletion of CD3+ T cells and CD83+ dendritic cells in lymphoid nodules that is independent of the stage of disease. We also determined that immature (CD1a) dendritic cells and CD25+ T cells did not appear to be either concentrated or depleted in lymphoid aggregates in rectal tumours. Lymphoid nodules in the colon and rectum have been virtually ignored until recently. Only Nascimbeni et al. [34] have described their morphology and distribution in both inflammatory and malignant conditions of the colon, and the number and distribution of these nodules in our study are consistent with previous studies [30].

The ubiquitous presence of these immune cell clusters and the morphological changes these nodules undergo in colorectal pathology may indicate an important role in immune function. T cell infiltration of tumours is considered an important prognostic marker, and recent work suggests that the quantity and subtype of T cells within tumours may be a better predictor of survival than the traditional tumour–node–metastasis (TNM) staging classification [36,37]. In our present work the increased CD3+ T cell infiltration of lymphoid nodules predicted improved survival consistent with a recent study of T cells in different sections of tumour core and margin [11]. Nagorsen et al. hypothesized that dendritic cell–T cell interactions determine immune stimulation or tolerance in colorectal cancer [13]. We suggest further that the co-localization of dendritic cells and T cells in lymphoid nodules is essential to that process. Lymphoid nodules may represent a mechanism for the presentation of tumour antigen to T cells in the context of colorectal malignancy. T cell–dendritic cell interactions outside lymphoid nodules may not contribute to stimulation but could induce tolerance, as proposed recently for breast cancer [32]. The complexity of the T cell responses is perhaps best illustrated by Galon et al. [36]. CD3, CD8, CD45 and GZMB+ cells predicted varying survival of colorectal cancer patients depending upon the degree of infiltration and whether the cells were found within the tumour stroma or at the margin. Additional work is needed to outline how the location and number of different antigen-presenting cells, including dendritic cells and macrophages, impact the adaptive immune response and patient survival [13]. By demonstrating concentrated levels of dendritic cells and T cells in lymphoid nodules in this study, we believe that lymphoid nodules may serve as an essential site to priming host immune responses to malignancy and it is this interaction that needs to be explored further.

Investigations of dendritic cell infiltration in response to colonic or other malignancy has produced a myriad of observations on the important location of infiltration and which dendritic subtypes are essential. Mature dendritic cells are now accepted as the end product of tumour sampling and the cells essential for presentation of tumour antigens to T cells. However, the spatial and temporal factors that drive clinically relevant antigen presentation and response remain unclear. The reasons for this are twofold. The first problem is that observations of tumour infiltration by dendritic cells in different reports have included tumour stroma, intra-epithelial component and tumour margin, while some studies do not specify any segment. Each of these tumour areas has been touted as an important site of dendritic cell exposure to tumour antigen. The second factor confounding the analysis is that different investigators have used different markers as surrogates for infiltration. Dendritic cells have been documented with non-specific markers such as S100 and HLA-DR, as well as markers for both immature and mature phenotypes including CD201, CD83 and CD86. In this study we chose to focus on the tumour margin and tumour-associated lymphoid nodules with markers for both immature (CD1a) and mature (CD83) dendritic cells. We have shown that mature dendritic cells are located preferentially in lymphoid nodules in both normal and diseased mucosa. The number of immature and mature dendritic cells observed scattered and isolated in the mucosa or tumour margin was low. This may indicate that antigen presentation to T cells by dendritic cells is completed primarily within tumour-associated lymphoid nodules. In contrast to previous studies, however, we found that dendritic cell infiltration of the tumour margin neither improved nor decreased survival [18–20]. In addition, the infiltration of scattered or isolated dendritic cells in the tumour margin was not linked with T cells, as indicated by previous studies [20]. Part of the explanation for these discrepancies is that the presence of tumour-associated lymphoid nodules may have confounded cell counts if included in the analysis. The significant co-localization of dendritic cells and T cells in lymphoid nodules is an important and novel observation that will require further study examining dendritic cell maturation and dynamic studies to demonstrate effective antigen presentation.

It is important to note that the markers used in this study represent a small fraction of the markers available to sample the different dendritic cell and T cell subpopulations. Our study was designed and powered to look only at large differences in overall infiltration of the tumour margin and lymphoid nodules in rectal cancer. Differences in staining techniques and quantification make comparison between studies difficult. It may be that other T cell or dendritic cell phenotypes not quantified here are depleted or concentrated in different stages of malignant growth [7]. The results of this study indicate that it is not only the number of dendritic cells and T cells infiltrating the tumour, but the location that that may impact the subsequent immune response and, ultimately, patient survival. More complex tissue microarray studies may help to understand more clearly the subtypes of both dendritic cells and T cells that drive a relevant clinical response. This has important ramifications for the ongoing work into dendritic cell vaccines under clinical trials [38].

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Edmonton Civic Employees Charitable Assistance Fund for their generous support of this work. Sunita Ghosh provided assistance with statistical analysis.

Disclosure

None.

References

- 1.Gattaj G, Ciccolallo L. Differences in colorectal cancer survival between European and US populations: the importance of sub-site and morphology. Eur J Cancer. 2003;39:2214–22. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(03)00549-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Troisi RJ, Freedman AN, Devesa SS. Incidence of colorectal carcinoma in the U.S.: an update of trends by gender, race, age, subsite, and stage, 1975–1994. Cancer. 1999;85:1670–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Manfredi S, Benhamiche AM, Meny B, et al. Population-based study of factors influencing occurrence and prognosis of local recurrence after surgery for rectal cancer. Br J Surg. 2001;88:1221–7. doi: 10.1046/j.0007-1323.2001.01861.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rajput A, Bullard Dunn K. Surgical management of rectal cancer. Semin Oncol. 2007;34:241–9. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2007.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gilboa EJ. Dendritic cell-based cancer vaccines. Clin Invest. 2007;117:1195–203. doi: 10.1172/JCI31205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mosca PJ, Lyerly HK, Clay TM, et al. Dendritic cell vaccines. Front Biosci. 2007;12:4050–60. doi: 10.2741/2371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nagorsen D, Thiel E. Clinical and immunologic responses to active specific cancer vaccines in human colorectal cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:3064–9. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-2788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jass JR. Lymphocytic infiltration and survival in rectal cancer. J Clin Pathol. 1986;39:585–9. doi: 10.1136/jcp.39.6.585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kreider JW, Bartlett GL, Butkiewicz BL. Relationship of tumor leucocytic infiltration to host defense mechanisms and prognosis. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 1984;3:53–74. doi: 10.1007/BF00047693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Talmadge JE, Donkor M, Scholar E. Inflammatory cell infiltration of tumors: Jekyll or Hyde. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2007;26:373–400. doi: 10.1007/s10555-007-9072-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Waldner M, Schimanski CC, Neurath MF. Colon cancer and the immune system: the role of tumor invading T cells. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:7233–8. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i45.7233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Banchereau J, Steinman R. Dendritic cells and the control of immunity. Nature. 1998;392:245–522. doi: 10.1038/32588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nagorsen D, Voigt S, Berg E, Stein H, Thiel E, Loddenkemper C. Tumor-infiltrating macrophages and dendritic cells in human colorectal cancer: relation to local regulatory T cells, systemic T-cell response against tumor-associated antigens and survival. J Transl Med. 2007;5:62–70. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-5-62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bell SJ, Rigby R, English N, et al. Migration and maturation of human colonic dendritic cells. J Immunol. 2001;166:4958–67. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.8.4958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Celluzi C, Falo L. Physical interaction between dendritic cells and tumor cells results in an immunogen that induces protective and therapeutic tumor rejection. J Immunol. 1998;160:3081–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ambe K, Mori M, Enjoji M. S-100 protein positive cells in colorectal adenocarcinomas. Cancer. 1989;63:496–503. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19890201)63:3<496::aid-cncr2820630318>3.0.co;2-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dadabayev AR, Sandel MH, Menon AG, et al. Dendritic cells in colorectal cancer correlate with other tumor-infiltrating immune cells. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2004;53:978–86. doi: 10.1007/s00262-004-0548-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sandel MH, Dadabayev AR, Menon AG, et al. Prognostic value of tumor-infiltrating dendritic cells in colorectal cancer: role of maturation status and intratumoral localization. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:2576–82. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-1448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schwaab T, Weiss JE, Schned AR, et al. Dendritic cell infiltration in colon cancer. J Immunother. 2001;24:130–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Suzuki A, Masuda A, Nagata H, et al. Mature dendritic cells make clusters with T cells in the invasive margin of colorectal carcinoma. J Pathol. 2002;196:37–43. doi: 10.1002/path.1018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chiba T, Ohtani H, Mizoi T, et al. Intraepithelial CD8+ T-cell-count becomes a prognostic factor after a longer follow-up period in human colorectal carcinoma: possible association with suppression of micrometastasis. Br J Cancer. 2004;91:1711–17. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Funada Y, Noguchi T, Kikuchi R, et al. Prognostic significance of CD8+ T cell and macrophage peritumoral infiltration in colorectal cancer. Oncol Rep. 2003;10:309–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Koch M, Beckhove P, Op den Winkel J, et al. Tumor infiltrating T lymphocytes in colorectal cancer: tumor-selective activation and cytotoxic activity in situ. Ann Surg. 2006;244:986–92. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000247058.43243.7b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Musha H, Ohtani H, Mizoi T, et al. Selective infiltration of CCR5(+)CXCR3(+) T lymphocytes in human colorectal carcinoma. Int J Cancer. 2005;116:949–56. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Naito Y, Saito K, Shiiba K, et al. CD8+ T cells infiltrated within cancer cell nests as a prognostic factor in human colorectal cancer. Cancer Res. 1998;58:3491–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.O'Learly AD, Sweeney EC. Lymphoglandular complexes of the colon: structure and distribution. Histopathology. 1986;10:267–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.1986.tb02481.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Prall F, Dührkop T, Weirich V, et al. Prognostic role of CD8+ tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes in stage III colorectal cancer with and without microsatellite instability. Hum Pathol. 2004;35:808–16. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2004.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sandel MH, Speetjens FM, Menon AG, et al. Natural killer cells infiltrating colorectal cancer and MHC class I expression. Mol Immunol. 2005;42:541–6. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2004.07.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Takemoto N, Konishi F, Yamashita K, et al. The correlation of microsatellite instability and tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes in hereditary non-polyposis colorectal cancer (HNPCC) and sporadic colorectal cancers: the significance of different types of lymphocyte infiltration. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2004;34:90–8. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hyh018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cameron IL, Kent JE, Philo R, et al. Numerical distribution of lymphoid nodules in the human sigmoid colon, rectosigmoidal junction, rectum and anal canal. Clin Anat. 2006;19:164–70. doi: 10.1002/ca.20167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dukes C, Bussey HJR. The number of lymphoid follicles of the human large intestine. J Pathol Bacteriol. 1926;29:111–6. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ménétrier-Caux C, Gobert M, Caux C. Differences in tumor regulatory T-cell localization and activation status impact patient outcome. Cancer Res. 2009;69:7895–8. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-1642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Langman JM, Rowland R. The number and distribution of lymphoid follicles in the human large intestine. J Anat. 1986;194:189–94. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nascimbeni R, Di Fabio F, Di Betta E, et al. Morphology of colorectal lymphoid aggregates in cancer, diverticular and inflammatory bowel diseases. Mod Pathol. 2005;18:681–5. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3800343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hui D, Reiman T, Hanson J, et al. Immunohistochemical detection of cdc2 is useful in predicting survival in patients with mantle cell lymphoma. Mod Pathol. 2005;18:1223–31. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3800409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Galon J, Costes A, Sanchez-Cabo F, et al. Type, density, and location of immune cells within human colorectal tumors predict clinical outcome. Science. 2006;313:1960–4. doi: 10.1126/science.1129139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pagès F, Berger A, Camus M, et al. Effector memory T cells, early metastasis, and survival in colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:2654–66. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa051424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Menon AG, Janssen-van Rhijn CM, Morreau H, et al. Immune system and prognosis in colorectal cancer: a detailed immunohistochemical analysis. Lab Invest. 2004;84:493–501. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3700055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]