Abstract

Mesenchymal stem cell (MSC) therapy has shown promise clinically in graft-versus-host disease and in preclinical animal models of T helper type 1 (Th1)-driven autoimmune diseases, but whether MSCs can be used to treat autoimmune disease in general is unclear. Here, the therapeutic potential of MSCs was tested in the New Zealand black (NZB) × New Zealand white (NZW) F1 (NZB/W) lupus mouse model. The pathogenesis of systemic lupus erythematosus involves abnormal B and T cell activation leading to autoantibody formation. To test whether the immunomodulatory activity of MSCs would inhibit the development of autoimmune responses and provide a therapeutic benefit, NZB/W mice were treated with Balb/c-derived allogeneic MSCs starting before or after disease onset. Systemic MSC administration worsened disease and enhanced anti-double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) autoantibody production. The increase in autoantibody titres was accompanied by an increase in plasma cells in the bone marrow, an increase in glomerular immune complex deposition, more severe kidney pathology, and greater proteinuria. Co-culturing MSCs with plasma cells purified from NZB/W mice led to an increase in immunoglobulin G antibody production, suggesting that MSCs might be augmenting plasma cell survival and function in MSC-treated animals. Our results suggest that MSC therapy may not be beneficial in Th2-type T cell- and B cell-driven diseases such as lupus and highlight the need to understand further the appropriate application of MSC therapy.

Keywords: autoimmune diseases, B lymphocytes, cellular therapy, lupus, mesenchymal stem cells

Introduction

Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs), multi-potent non-haematopoietic stem cells residing in the bone marrow, support haematopoeisis [1] and can differentiate into cells of the mesenchymal lineage [2]. MSCs home to areas of tissue injury and participate in tissue repair [3], and have been described to possess anti-inflammatory and immunosuppressive properties. MSCs inhibit T cell proliferation [4–8], down-regulate cytotoxic T cell [9,10] and natural killer (NK) cell [11,12] responses, inhibit dendritic cell maturation and antigen presentation [13–16], interfere with B cell proliferation [17–19], and modulate macrophage function [20,21]. Their activity involves contact-dependent and -independent mechanisms including the production of immunosuppressive mediators such as transforming growth factor (TGF)-β[4], IDO [22], nitric oxide [23,24], prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) [25], hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) [4] and interleukin (IL)-10 [14]. Most of these observations have come from in vitro studies, but MSC administration in autoimmune disease models and in patients with graft-versus-host disease supports the concept that MSCs have the potential to control autoimmune and inflammatory responses. MSC therapy inhibits T cell responses and ameliorates disease symptoms in collagen-induced arthritis [26], experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis [27–29] and type 1 diabetes mouse models [30,31]. Unlike these models believed to involve T helper type 1 (Th1) T cell responses, we explored MSC therapy in lupus, a disease driven largely by Th2-type T cell and B cell responses leading to pathogenic autoantibody production and immune complex deposition in the kidney, resulting in inflammation and tissue damage [32]. Our results show that allogeneic MSCs do not provide a benefit to New Zealand black (NZB) × New Zealand white (NZW) F1 (NZB/W) mice and appear to exacerbate disease.

Materials and methods

MSC generation and propagation

Bone marrow cells from 6–8-week-old Balb/c mice (Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME, USA) were plated at 10–12 × 106 cells per 25 mm2 tissue culture flask in high-glucose Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 1× penicillin/streptomycin and 2 mM L-glutamine. Spent media was replaced 3–5 days later and on day 7 the adherent cells were harvested by trypsin-ethylenediamine tetraacetic acid (EDTA) treatment and gentle scraping and passaged every 3–4 days upon reaching 80–90% confluency for up to eight passages. MSCs exhibited the expected phenotype by fluorescence activated cell sorter (FACS) analysis [CD34–CD44+CD105+ major histocompatibility complex (MHC) I+MHC II−; data not shown]. Culture reagents were purchased from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA, USA).

MSC differentiation

MSCs were plated at 1 × 104 cells/cm3 in 6 well plates and incubated in maintenance medium until confluent. All differentiation culture conditions have been described previously [33]. Briefly, for adipogenesis, cells were incubated in Iscove's modified Dulbecco's medium (IMDM) containing 20% serum (10% horse and 10% bovine sera), insulin, indomethacin, dexamethasone and 3-isobutyl-1-methylxanthine (IBMX) for 3 weeks then stained with Oil Red O (Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA) to detect fat drops in cells. For osteogenesis, cells were incubated in IMDM medium containing 20% serum (10% horse and 10% bovine sera), β-glycerol phosphate, thyroxine, dexamethasone and ascorbate-2-phosphate for 3 weeks and stained for alkaline phosphatase activity by incubating with 0·005 g napthol in N,N dimethylformamide, Tris-hydrochloride (HCL) pH 8·3, distilled water and 0·03 g red violet LB salt for 45 min followed by a 30 min incubation with 2·5% sodium nitrate to detect mineralized bone. For chondrogenesis, 250 000 MSCs were grown in pellets for 3 weeks in medium containing DMEM high-glucose, BMP6 (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA), TGF-β3 (R&D Systems), dexamethasone, ascorbate-2-phosphate, proline, pyruvate and ITS+ premix (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA). Pellets were sectioned and stained for toluidine blue to detect extracellular matrix. Unless stated otherwise, chemicals were purchased from Sigma (St Louis, MO, USA).

Proliferation assay

Proliferation of Balb/c splenocytes (500 000/well) stimulated with 2 µg/ml plate-bound anti-mouse CD3ε (BD Biosciences) with or without Balb/c MSCs for 4 days was measured by tritiated thymidine (Perkin Elmer, Boston, MA, USA) incorporation.

Lupus model and treatment

Female NZB/W mice (Jackson Laboratory) were treated bi-weekly with intraperitoneal injections of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), 1 × 106 allogeneic Balb/c MSCs starting at 21 or 32 weeks of age, prior to or after disease onset when anti-dsDNA antibodies and elevated proteinuria were detected, or weekly with 50 mg/kg cyclophosphamide (Sigma). PBS and cyclophosphamide administration started at 21 weeks of age. The study protocol was approved by Genzyme's Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) and was conducted in Genzyme's Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care (AAALAC)-accredited facility.

Evaluation of proteinuria and anti-dsDNA titres

Urine proteinuria was measured using the Micro Pyrogallol Red total protein kit (Sigma). Serum anti-dsDNA antibody titres were assessed by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) using plates pretreated with 0·01% protamine sulphate and coated with S1-nuclease-treated NZB/W dsDNA (Jackson Laboratory) (1 µg/ml dsDNA, 100 µl/well). Serial twofold dilutions of serum were added and bound antibody was detected with horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated goat anti-mouse immunoglobulin G (IgG) (Pierce, Rockford, IL, USA). The absorbance at 490 and 650 nM was read on a dual wavelength plate reader (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA, USA). The antibody titre was defined as the reciprocal of the serum dilution giving an optical density (OD) > 0·1. Normal and aged lupus mice sera served as negative (titre < 200, the lowest dilution tested) and positive (titre of 25 600) controls, respectively. Statistical analysis was performed using Fisher's exact test and Student's t-test for the proteinuria and dsDNA antibody titre data, respectively.

Histopathology

Kidneys harvested at the time of killing were fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin, paraffin-embedded and stained with haematoxylin and eosin (H&E) and periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) stains (3-µm sections) for histological analysis or snap-frozen in Tissue-Tek OCT compound (Sakura Finetek, Torrance, CA, USA) for immune complex deposition analysis. Slides were scored in a blinded fashion by a board-certified veterinary pathologist for glomerular pathology, interstitial inflammation and fibrosis and intra-tubular protein cast formation. Statistical analysis was performed using a non-parametric Kruskal–Wallis test followed by a Dunn's test comparing all treatment groups.

Glomeruli were scored on a scale of 0–6 as follows: 0, absence of significant lesions; 1 and 2, minimal to mild disease characterized by mesangial deposits or hypercellularity with or without mesangial deposits, respectively; 3 and 4, moderate to severe disease characterized by mesangioproliferative glomerulopathy and ‘wire loop’ capillaries with or without fibrinoid necrosis of capillary loops, intraglomerular cellular crescents, synechia, rupture of Bowman's capsule and periglomerular inflammation and fibrosis affecting less than 25% of the glomeruli or 25–50% of the glomerular tufts, respectively; 5 and 6, severe disease with the same characteristics as score 3 but affecting 50–75% or greater than 75% of the glomerular tufts, respectively.

Interstitial inflammation and fibrosis and intratubular protein cast formation were scored on a severity scale of 0–4, with 0 being assigned in the absence of significant lesions. For interstitial inflammation and fibrosis, scores of 1–4 were assigned for minimal, mild, moderate or severe inflammation/fibrosis, respectively. For intratubular protein cast formation, scores of 1–4 were assigned when proteinaceous material was noted within less than 5% (minimal), 5–25% (mild), 25–50% (moderate) or more than 50% of renal tubules, respectively.

Evaluation of immune complex deposition

Acetone-fixed frozen tissue sections were stained with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG2a antibody (Southern Biotechnology, Birmingham, AL, USA), mounted (Vectashield, Burlingame, CA, USA) and examined microscopically (Olympus IX70). The average intensity of glomerular immune complex deposition in five independent fields of one kidney section per animal was quantitated using MetaMorph software and statistical analysis was performed using Student's t-test.

Plasma cell staining

At the time of killing, bone marrow cells were stained with phycoerythrin (PE)-labelled anti-mouse CD138, peridinin chlorophyll (PerCP)-labelled anti-mouse B220, allophycocyanin (APC)-labelled anti-mouse T cell receptor (TCR)-β and unlabelled anti-mouse Ig,κ then fixed and permeabilized, stained with FITC-labelled anti-mouse IgG1, IgG2a and IgG2b to detect intracellular IgG, and acquired on the LSRII cytometer (BD Biosciences). Data were analysed using FlowJo software (Treestar, Ashland, OR, USA). All antibodies were purchased from BD Biosciences.

In vitro co-culture of MSCs and plasma cells

Plasma cells (10 000 cells) isolated from the spleen, bone marrow and kidney [34] of 4- or 8-month-old NZB/W mice using the CD138 plasma cell isolation kit (Miltenyi Biotec, Auburn, CA, USA) were cultured alone or together with mitomycin-C treated Balb/c MSCs in RPMI-1640 supplemented with 10% FBS, 1× penicillin/streptomycin, 2 mM L-glutamine and 50 µM 2-mercaptoethanol for 7 days at 37°C, 5% CO2. The 8-month-old NZB/W mice had lupus disease (high anti-dsDNA autoantibody titres). IgG in supernatants collected on day 7 was measured by quantitative ELISA.

For normal plasma cell-MSC co-cultures, splenocytes (6 × 107 cells/plate) from B6C3F1 mice (Jackson Laboratory) immunized intraperitoneally with 25 µg ovalbumin (OVA) (Sigma) in complete Freund's adjuvant (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL, USA) followed by two subsequent OVA (25 µg) immunizations in incomplete Freund's adjuvant (Thermo Scientific) given in at least 2-week intervals were added to Petri plates alone or containing B6C3F1-derived MSCs that had been plated 2 days prior with 500 000 MSCs/plate and cultured in RPMI-1640 containing 10% FBS, 1× penicillin/streptomycin, and 2 mM L-glutamine supplemented with 200 U/ml IL-2 and 50 ng/ml IL-10 (R&D Systems) at 37°C, 5% CO2. After 4 days, the number of OVA-specific IgG antibody forming cells (AFCs) in the non-adherent cells was assessed by enzyme-linked immunospot assay (ELISPOT).

Quantitative ELISA and ELISPOT

Serial twofold dilutions of supernatants or mouse IgG standard (50 ng/ml) were added to ELISA plates coated with unlabelled goat anti-mouse IgG (γ-specific) antibody (5 µg/ml in 100 mM sodium bicarbonate buffer, pH 9·2). Bound IgG was detected with biotin-labelled goat anti-mouse IgG and streptavidin-HRP. The absorbance at 450 and 540 nm was measured on a dual-wavelength plate reader (Molecular Devices). Statistical analysis was performed using Student's t-test.

For ELISPOT assays, serial twofold dilutions of splenocytes (top well 50 000 cells added) cultured with or without MSCs were added to sterile 96-well filter-bottomed plates (Millipore) coated with OVA (5 µg/ml). After 24 h, cells were washed away and anti-OVA IgG was detected with an alkaline phosphatase (AP)-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG followed by nitro blue tetrazolium chloride (NBT)/5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl phosphate (BCIP) substrate (KPL, Gaithersburg, MD, USA) detection. Spots enumerated microscopically were calculated as the percentage of AFCs of the cells originally plated in the assay. All antibodies and streptavidin-HRP were purchased from Southern Biotechnology.

Cytokine analysis of MSC supernatants

Supernatants from Balb/c MSC or plasma cell-only cultures or plasma cell and MSC co-cultures were harvested on day 8 and tested using the Milliplex™ MAP 22-plex kit (Millipore) following the manufacturer's instructions and acquired on a Luminex IS 2.3 machine (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). Plasma cells were isolated from diseased NZB/W mice as described above. The unknown concentrations were extrapolated from a standard curve for each factor.

Results

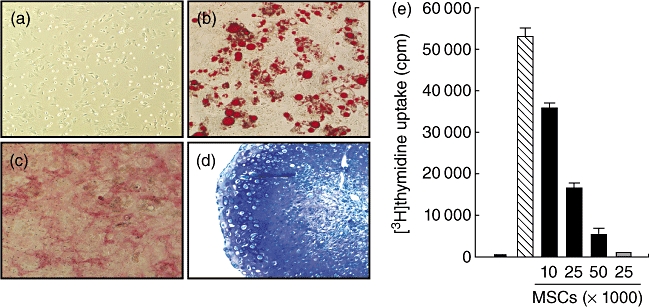

MSCs suppress T cell proliferation

MSCs have been shown to possess immunosuppressive activity (see [35] for review). We qualified our MSCs by subjecting them to differentiation analysis. Under specific culture conditions [33], our MSCs differentiated into fat, bone and cartilage as indicated by Oil Red O (red), alkaline phosphatase (pink) and silver nitrate (black), and toluidine blue (purple centre) staining, respectively (Fig. 1a–d). To confirm that our MSCs were immunomodulatory, the ability of the MSCs to suppress T cell proliferation in vitro was tested. The MSCs arrested T cell proliferation in a dose-dependent fashion (Fig. 1e). Also, MSCs alone did not activate T cells, which is not surprising as under these conditions MSCs express little to no MHC class II or co-stimulatory molecules (Fig. 1e, grey bar).

Fig. 1.

Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) differentiate into cells of the mesenchymal lineage and inhibit T cell proliferation. (a–d) MSCs were subjected to differentiation culture conditions for 21 days as described in Materials and methods and stained with Oil Red O, alkaline phosphatase and silver nitrate, or toluidine blue for adipose (b), bone (c) or cartilage (d) differentiation, respectively. MSCs before being subjected to differentiation conditions are shown in (a). Magnification: 20×. (e) Balb/c spleen cells were cultured alone (white bar) or with anti-CD3 antibody (aCD3) in the absence (hatched bar) or presence of the indicated doses of Balb/c MSCs (black bars) for 4 days. Grey bar represents spleens cells cultured with MSCs but without aCD3. Proliferation was measured by tritiated thymidine incorporation.

MSC treatment enhances autoantibody production and immune complex deposition

Allogeneic MSCs have been reported to suppress MHC-unrelated T cell responses in vitro [4–8] and are considered largely non-immunogenic, given their lack of co-stimulatory molecule and MHC class II expression. Furthermore, repeated allogeneic MSC administration has been used successfully in animal models [5,26,27] and clinically to treat graft-versus-host disease [36,37]. Given these well-described immunosuppressive properties of allogeneic MSCs, we postulated that systemic administration in the NZB/W spontaneous lupus mouse model may be beneficial. MSC treatment was initiated before or after disease onset, as measured by the appearance of anti-dsDNA antibodies and elevated proteinuria. We administered normal allogeneic MSCs derived from Balb/c mice, given recent data suggesting that MSCs derived from lupus-prone mice and autoimmune lupus patients have intrinsic defects [38,39].

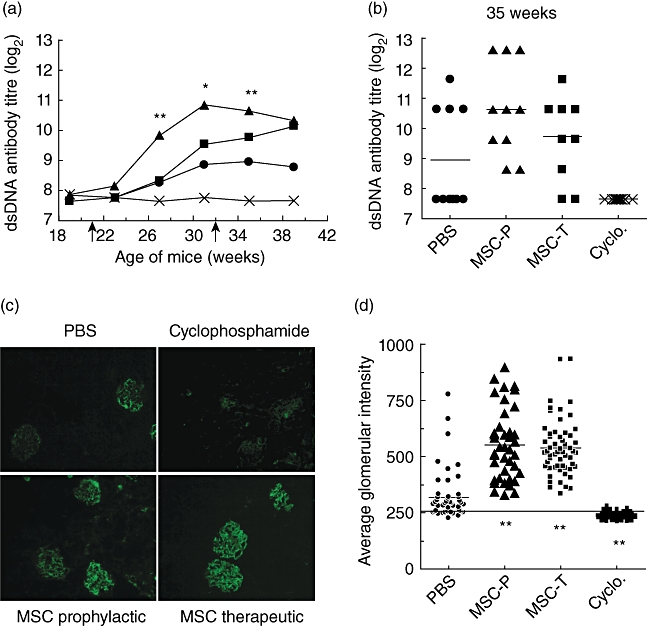

Sera were collected monthly to monitor anti-dsDNA autoantibody development. MSC treatment did not inhibit the rise in anti-dsDNA antibody titres but increased the amount of detectable antibodies in this group (Fig. 2a,b). At 27, 31 and 35 weeks of age, anti-dsDNA antibody titres in mice receiving MSCs prophylactically were significantly higher from levels in PBS-treated mice. Mice receiving MSCs therapeutically had higher anti-dsDNA titres that were not significantly different from those in PBS-treated animals, suggesting that the effect was most pronounced in the group for which MSC treatment was initiated earlier. Cyclophosphamide treatment suppressed anti-dsDNA antibody development effectively.

Fig. 2.

Enhanced autoantibody production and immune complex deposition in mesenchymal stem cell (MSC)-treated mice. (a) Average anti-dsDNA immunoglobulin (Ig)G titres in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (circle), MSCs delivered prophylactically (triangle) or therapeutically (square) and cyclophosphamide (cross)-treated mice. Each group contains 10 mice. Arrows indicate the start of prophylactic (21 weeks) or therapeutic (32 weeks) MSC treatment. PBS versus prophylactic MSC treatment: *P < 0·05; **P < 0·001. (b) Anti-dsDNA IgG titres for individual animals in PBS, MSCs delivered prophylactically (MSC-P) or therapeutically (MSC-T) and cyclophosphamide (Cyclo.)-treated mice at 35 weeks of age. The line represents the mean value for each group. (c) Kidney sections stained for mouse IgG (20×). Results are representative of four mice/group. (d) Average fluorescence intensity of IgG staining in glomeruli from PBS, MSCs delivered prophylactically (MSC-P) or therapeutically (MSC-T) and cyclophosphamide (Cyclo.)-treated mice. Each point represents the average intensity of immune complex deposits in all the glomeruli per field in a kidney section for each animal. The line represents the average background autofluorescence on sections stained with an isotype control antibody. PBS versus MSC treatment **P < 0·001.

The increase in anti-dsDNA titres correlated with the amount of immune complex deposits in the kidney, as detected by immunofluorescent staining (Fig. 2c). The average fluorescence intensity in glomeruli from MSC-treated mice was significantly higher than in PBS-treated animals (PBS: 320 ± 107; MSC-P: 553·5 ± 156·5; MSC-T: 537·6 ± 123·6; P < 0·001). Kidneys from cyclophosphamide-treated mice exhibited little or no fluorescence above background, indicating minimal immune complex deposition in these animals (Fig. 2d).

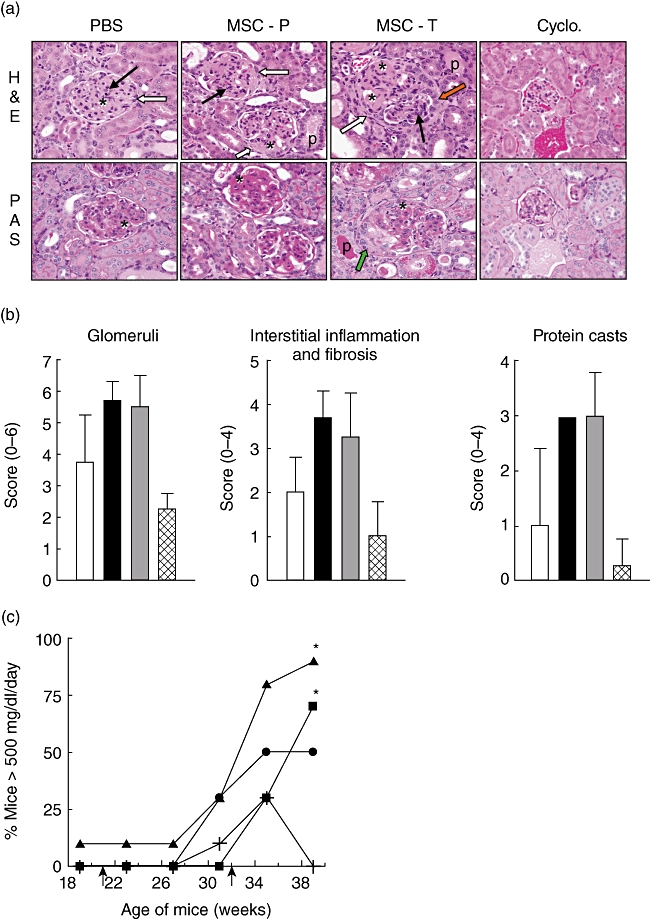

MSC treatment enhances kidney pathology and proteinuria

Immune complex deposition leads to inflammation and kidney damage. To assess the pathological impact of MSC treatment on the associated enhancement of autoantibody formation and immune complex deposition, kidneys were collected for histological analysis. MSC administration exacerbated the severity of glomerulonephritis, as evident by an increase in glomerular hypercellularity and intratubular protein casts, more frequent adhesions to the Bowman's capsule, parietal cell hypertrophy and occasional cellular crescents within the urinary space and an increase of basement membrane thickening, as indicated by more PAS-positive staining (Fig. 3a). Overall, MSC-treated mice had more severe renal pathology, including glomerulonephritis, interstitial inflammation and fibrosis, and tubular protein cast formation compared to PBS-treated animals, although the values were not significantly higher (Fig. 3b). By comparison, cyclophosphamide treatment reduced renal pathology.

Fig. 3.

Enhanced glomerulonephritis in mesenchymal stem cell (MSC)-treated mice. (a) Kidney sections were stained with haematoxylin and eosin (H&E; top panels) and periodic acid-Schiff (PAS; bottom panels) stains. Asterisks indicate increased PAS-positive material expanding the mesangium. Black and white arrows denote hypercellularity and adhesions to the Bowman's capsule, respectively. Orange and green arrows show parietal cell hypertrophy and a cellular crescent, respectively. P indicates intratubular protein casts. Results are representative of four mice/group. (b) H&E-stained kidney sections from PBS (white bar), MSCs delivered prophylactically (black bar) or therapeutically (grey bar) and cyclophosphamide (hatched bar)-treated mice were scored as described in Materials and methods. (c) The percentage of mice with greater than 500 mg/dl/day of total protein in urine collected from animals treated with PBS (circle), MSCs delivered prophylactically (triangle) or therapeutically (square) and cyclophosphamide (cross). Arrows indicate the start of prophylactic (21 weeks) or therapeutic (32 weeks) MSC treatment. PBS versus prophylactic MSC treatment: *P < 0·05.

Consistent with the increase in renal pathology, the incidence of severe proteinuria was greater in MSC-treated mice compared to PBS-treated mice, while cyclophosphamide treatment inhibited proteinuria development (Fig. 3c). Together, these data suggest that disease was exacerbated in MSC-treated mice.

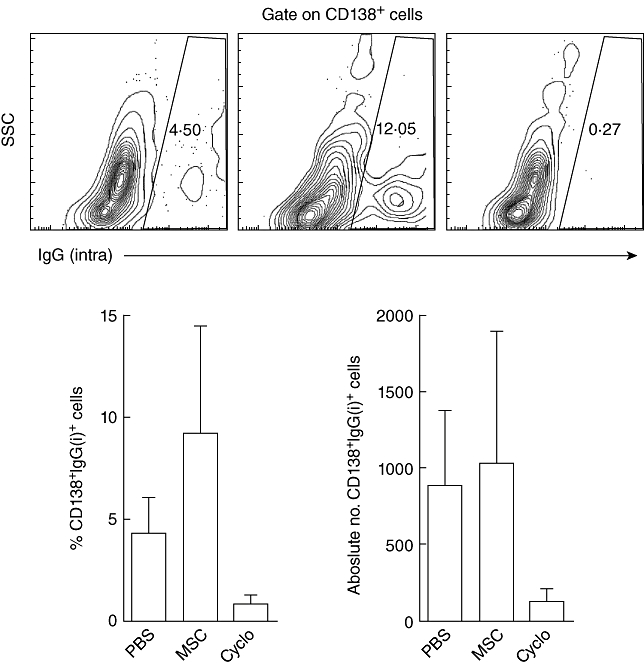

Plasma cells in MSC-treated mice

Because anti-dsDNA IgG autoantibody titres were elevated in MSC-treated mice, IgG-secreting plasma cells were characterized by flow cytometry as identified by surface CD138 and intracellular IgG expression. IgG-secreting plasma cells were detectable in the bone marrow (Fig. 4, top panels) and the percentage of plasma cells was increased in mice receiving MSCs, but there was no marked elevation in the absolute number of plasma cells (Fig. 4, bottom panels). Few plasma cells were present in cyclophosphamide-treated mice, which correlated with the absence of anti-dsDNA autoantibodies and immune complex deposits in these animals. These data suggest that MSCs might be affecting plasma cell function and survival in the bone marrow leading to elevated anti-dsDNA antibody titres and immune complex deposits.

Fig. 4.

Increased percentage of immunoglobulin (Ig)G+ plasma cells in mesenchymal stem cell (MSC)-treated mice. Bone marrow cells from phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (top left), MSCs delivered therapeutically (top middle) and cyclophosphamide (top right)-treated mice stained for CD138 and intracellular (intra) IgG. Contour plots are representative of four mice/group. Bar graphs depict the percentage (bottom left) and absolute number (bottom right) of IgG+ plasma cells.

Increased antibody production when plasma cells are co-cultured with MSCs

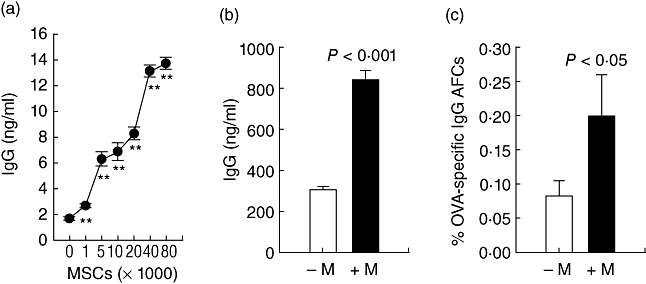

Because plasma cells die in culture within 3 days unless stimulated by cytokines [40], we asked if MSCs affect plasma cell survival and function directly by testing supernatants from NZB/W plasma cells cultured with or without Balb/c MSCs for 7 days for the presence of IgG. IgG was detected in wells containing plasma cells alone, but the amount of IgG was higher when MSCs were present (Fig. 5a,b) and rose as more MSCs were added (Fig. 5a). MSCs enhanced the survival and function of plasma cells specific to foreign antigen, because splenocytes from OVA immunized mice cultured with MSCs contained more OVA-specific IgG AFCs than those cultured without MSCs (Fig. 5c), indicating that the effect of MSCs is not specific to autoreactive plasma cells.

Fig. 5.

Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) promote the production of IgG by plasma cells. (a) Total immunoglobulin (Ig)G in supernatants from plasma cells from 4-month-old New Zealand black/white (NZB/W) mice cultured with or without MSCs. P < 0·001. (b) Total IgG in supernatants from plasma cells from diseased 8-month-old mice cultured with (+M) or without (−M) 10 000 MSCs. (c) Ovalbumin (OVA)-specific IgG antibody forming cells in splenocytes from OVA-immunized mice cultured with (+M) or without (−M) 500 000 MSCs.

MSCs produce cytokines and chemokines that support plasma cells

To gain a better understanding of potential mechanism(s) by which MSCs enhance anti-dsDNA antibody levels, the presence of cytokines was tested in plasma cell–MSC co-culture supernatants. IgG was the only soluble factor detected in plasma cell-only cultures, proinflammatory chemokines and cytokines such as IL-6 and IL-13 were consistently present in MSC-only cultures and the levels were higher in cultures containing more MSCs (Table 1). As expected, more IgG was present in supernatants from co-cultures containing more MSCs and many factors, including IL-5, IL-6, IL-10, IL-13, interferon inducible protein (IP)-10, monocyte chemoattractant protein (MCP)-1, regulated upon activation normal T cell expressed and secreted (RANTES) and tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-α were higher in the co-cultures, whereas IL-7, keratinocyte (KC) and macrophage inflammatory protein (MIP)-1α were consistently lower. These data suggest that there was cross-talk between the plasma cells and MSCs which led to a modulation of soluble factors produced by the cells in the co-cultures that might have contributed to plasma cell survival and function, as indicated by the increase in IgG in the co-cultures.

Table 1.

Soluble factors in mesenchymal stem cell (MSC) only, plasma cell (PC) only or PC + MSC co-culture supernatants.

| 10 000 MSCs |

40 000 MSCs |

80 000 MSCs |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PC alone |

−PC |

+PC |

−PC |

+PC |

−PC |

+PC |

|

| IgG (ng/ml) | 57 ± 1·5 | n.d. | 150·9 ± 19·7 | n.d. | 249·5 ± 11·5 | n.d. | 437·1 ± 29·7 |

| IL-4 (pg/ml)† | 0·58 | 1·16 | 0·89 | n.d. | 0·58 | 1·41 | 2·84 |

| IL-5 | n.d. | 3·36 | n.d. | n.d. | 4·4 | n.d. | 6·12 |

| IL-6 | n.d. | 26·86 | 27·1 | 22·62 | 29·29 | 39·22 | 46·86 |

| IL-7 | n.d. | 16·88 | 8·81 | 26·18 | 17·64 | 32·3 | 21·86 |

| IL-10 | n.d. | 11·13 | n.d. | n.d. | 4·14 | 4·14 | 17·38 |

| IL-12p70 | n.d. | n.d. | 12·94 | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | 16·89 |

| IL-13 | n.d. | 1·70 | 9·39 | 4·06 | 33·71 | 12·4 | 20·31 |

| IP-10 | n.d. | 42·45 | 80·92 | 86·18 | 380·03 | 97·41 | 145·2 |

| KC | n.d. | 125·61 | 115·95 | 286·04 | 167·85 | 428·34 | 240·94 |

| MCP-1 | n.d. | 1382·65 | 2529 | 1971 | 2822·43 | 2232·98 | 3406·04 |

| MIP-1α | n.d. | 757·41 | 284·32 | 899·62 | 412·19 | 722·5 | 401·72 |

| RANTES | 1·22 | 63·24 | 124·17 | 86·61 | 115·31 | 91·46 | 118·82 |

| TNF-α | n.d. | 5·25 | 9·01 | 7·66 | 8·36 | 9·33 | 10·82 |

The units of each cytokine concentration are pg/ml. IgG, immunoglobulin G; IL, interleukin; KC, keratinocyte; MCP, monocyte chemoattractant protein; MIP, macrophage inflammatory protein; n.d., not detected; RANTES, regulated upon activation normal T cell expressed and secreted; TNF, tumour necrosis factor.

Discussion

Growing evidence indicates that MSCs possess immunomodulatory activity. Inflammatory cytokines [6,22,24] recruit MSCs and trigger their immunosuppressive and anti-inflammatory activity, which is mediated by contact-dependent and -independent mechanisms [41]. These findings have raised the possibility of using MSCs as immunosuppressive agents [42]. The potential of MSC therapy has been explored in Th1-driven autoimmune disease models and treatment with syngeneic or allogeneic MSCs was found to provide a benefit [26–31].

We explored the therapeutic potential of MSCs in lupus, a disease driven primarily by Th2-type T cell and B cell responses leading to pathogenic autoantibody formation. MSC treatment had potential to be beneficial in lupus, because MSCs had been shown to inhibit B cell proliferation and antibody production in vitro[17–19]. Interestingly, MSC therapy failed to provide a benefit and exacerbated disease in NZB/W mice. Anti-dsDNA antibody formation and immune complex deposition were enhanced and more pronounced in mice for which MSC treatment was initiated earlier and that received the longest treatment course. Kidney histology also revealed an increase in glomerular pathology, interstitial fibrosis and inflammation and intratubular protein cast formation in MSC-treated mice compared to vehicle-treated animals.

Consistent with the increase in anti-dsDNA antibodies, the percentage of plasma cells was elevated in the bone marrow of MSC-treated mice. Given that long-lived plasma cells reside in the bone marrow [43–45], our data suggest that MSCs are affecting long-lived plasma cells in the lupus animals. Because MSCs are a component of bone marrow stroma that normally functions to support haematopoiesis [1] and plasma cell survival [46], it is conceivable that MSCs support plasma cell survival and that exogenously delivered MSCs home to the bone marrow [47–49] and enhance the survival niches protecting autoreactive plasma cells in NZB/W mice.

Our findings agree with reports showing that MSCs enhance antibody production in vitro. When added to unfractionated splenocytes or purified B cells [50,51], normal allogeneic MSCs enhanced IL-6 production, a cytokine shown to support plasma cell differentiation and their long-term maintenance [46,52,53], B cell proliferation and antibody production via contact-dependent and independent mechanisms, respectively. Importantly, the proliferation and differentiation of normal donor and lupus patient B cells were enhanced when the B cells were cultured with normal allogeneic MSCs [50]. Because the MSCs were added at culture initiation, MSCs could be affecting multiple stages of B cell activation and differentiation. Here, we cultured MSCs with plasma cells isolated from wild-type and lupus mice and show that MSCs affect plasma cells directly and enhance their antibody production.

Contradictory reports show that the proliferation of and antibody production by human B cells or splenocytes from BXSB mice, another lupus model, are inhibited when cultured with human MSCs [17] or Balb/c MSCs [54], respectively. Such discrepancies can be due to many factors, including differences in culture conditions, ratios of MSCs to target cells, stimuli used to activate B cells, etc. Depending on the nature and strength of the B cell stimulus and MSC dose, IgG production could be enhanced or inhibited in the presence of MSCs [51]. This observation stresses the importance of using in vivo systems to evaluate more accurately the ultimate impact of MSC administration in the context of disease conditions that cannot be replicated completely in vitro. MSCs have been shown to inhibit normal antibody responses to foreign protein in a mouse model of haemophilia A [55], but our data in lupus indicate that in a chronic disease with systemic inflammation, MSC therapy has the potential to exacerbate disease and may be contraindicated. Whether this phenomenon is applicable to other autoimmune diseases driven by pathogenic Th2 T cells and antibodies remains to be determined.

The production of specific cytokines and chemokines by MSCs might be one mechanism by which the cells promoted plasma cell survival and autoantibody production in the context of lupus. MSCs secrete IL-6 and IL-10, Th2-type cytokines known to promote B cell proliferation and differentiation [50,51] and prolong plasma cell survival in culture [40], and these cytokines, along with IL-5 and IL-13, are increased in plasma cell-MSC co-cultures. IL-5 and IL-13 also are known to support the differentiation of mature B cells into antibody secreting cells [56,57]. MSCs shift the cytokine profile from a Th1- to a Th2-type in a mixed lymphocyte reaction, which parallels the suppression of T cell responses in the cultures [25], suggesting that MSCs promote Th2 responses that might have contributed to the increased antibody production and worsening of disease observed in NZB/W lupus mice. MSCs also produce proinflammatory mediators such as IP-10, RANTES, MCP-1, MIP-1α and TNF-α that in the lupus disease setting may augment the inflammatory response and ultimately worsen the disease. This is consistent with an increase in IP-10, RANTES, MCP-1 and TNF-α seen in the plasma cell-MSC co-cultures. Furthermore, plasma cells express CXCR3 and home to sites of inflammation, such as the kidney in NZB/W mice [34], in response to CXCR3 ligands including IP-10 [58]. Interestingly, IL-7 and MIP-1α were decreased in the co-cultures. IL-7 is known to support early B cell development [56] and MIP-1α has been reported to induce the proliferation and survival of multiple myeloma cells, but whether this is true for non-malignant plasma cells is unknown [59]. No difference in the serum Th1/Th2 cytokine profile of MSC-treated mice was detected (data not shown), but such changes might be detectable only locally at sites of inflammation, not systemically.

MSC therapy has shown clinical benefit in graft-versus-host disease, suggesting MSCs have the ability to dampen deleterious immune responses in patients. Data in Th1-driven autoimmune disease models suggest that MSCs may provide some clinical benefit to patients with diseases such as multiple sclerosis, rheumatoid arthritis and type 1 diabetes. The MSC dose used here and in most animal studies is much higher than the dose used in the clinical setting [60]. Even though there were no deleterious affects or ectopic tissue formation, this should be considered when translating any animal findings to the clinic. Our work highlights the importance of testing MSC therapy in different disease settings. Although MSC therapy is efficacious in Th1-driven autoimmune diseases, each disease setting is unique and our findings warrant further investigation before clinical translation of MSC therapy in B cell-driven diseases.

Acknowledgments

We thank Lucy Philips for her help in scoring the renal pathology and Jason Durand for his work on the co-culture of MSCs with splenocytes derived from OVA-immunized mice.

Disclosure

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Dazzi F, Ramasamy R, Glennie S, Jones SP, Roberts I. The role of mesenchymal stem cells in haemopoiesis. Blood Rev. 2006;20:161–71. doi: 10.1016/j.blre.2005.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pittenger MF, Mackay AM, Beck SC, et al. Multilineage potential of adult human mesenchymal stem cells. Science. 1999;284:143–7. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5411.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Karp JM, Leng Teo GS. Mesenchymal stem cell homing: the devil is in the details. Cell Stem Cell. 2009;4:206–16. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2009.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Di Nicola M, Carlo-Stella C, Magni M, et al. Human bone marrow stromal cells suppress T-lymphocyte proliferation induced by cellular or nonspecific mitogenic stimuli. Blood. 2002;99:3838–43. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.10.3838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bartholomew A, Sturgeon C, Siatskas M, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells suppress lymphocyte proliferation in vitro and prolong skin graft survival in vivo. Exp Hematol. 2002;30:42–8. doi: 10.1016/s0301-472x(01)00769-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Krampera M, Glennie S, Dyson J, et al. Bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells inhibit the response of naive and memory antigen-specific T cells to their cognate peptide. Blood. 2003;101:3722–9. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-07-2104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tse WT, Pendleton JD, Beyer WM, Egalka MC, Guinan EC. Suppression of allogeneic T-cell proliferation by human marrow stromal cells: implications in transplantation. Transplantation. 2003;75:389–97. doi: 10.1097/01.TP.0000045055.63901.A9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Le Blanc K, Tammik L, Sundberg B, Haynesworth SE, Ringden O. Mesenchymal stem cells inhibit and stimulate mixed lymphocyte cultures and mitogenic responses independently of the major histocompatibility complex. Scand J Immunol. 2003;57:11–20. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3083.2003.01176.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Potian JA, Aviv H, Ponzio NM, Harrison JS, Rameshwar P. Veto-like activity of mesenchymal stem cells: functional discrimination between cellular responses to alloantigens and recall antigens. J Immunol. 2003;171:3426–34. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.7.3426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rasmusson I, Ringden O, Sundberg B, Le Blanc K. Mesenchymal stem cells inhibit the formation of cytotoxic T lymphocytes, but not activated cytotoxic T lymphocytes or natural killer cells. Transplantation. 2003;76:1208–13. doi: 10.1097/01.TP.0000082540.43730.80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sotiropoulou PA, Perez SA, Gritzapis AD, Baxevanis CN, Papamichail M. Interactions between human mesenchymal stem cells and natural killer cells. Stem Cells. 2006;24:74–85. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2004-0359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Spaggiari GM, Capobianco A, Abdelrazik H, Becchetti F, Mingari MC, Moretta L. Mesenchymal stem cells inhibit natural killer-cell proliferation, cytotoxicity, and cytokine production: role of indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase and prostaglandin E2. Blood. 2008;111:1327–33. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-02-074997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jiang X-X, Zhang B, Zhang S-X, Wu Y, Yu X-D, Mao N. Human mesenchymal stem cells inhibit differentiation and function of monocyte-derived dendritic cells. Blood. 2005;105:4120–6. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-02-0586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Beyth S, Borovsky Z, Mevorach D, et al. Human mesenchymal stem cells alter antigen-presenting cell maturation and induce T-cell unresponsiveness. Blood. 2005;105:2214–19. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-07-2921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nauta AJ, Kruisselbrink AB, Lurvink E, Willemze R, Fibbe WE. Mesenchymal stem cells inhibit generation and function of both CD34+-derived and monocyte-derived dendritic cells. J Immunol. 2006;177:2080–7. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.4.2080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang W, Ge W, Li C, et al. Effects of mesenchymal stem cells on differentiation, maturation, and function of human monocyte-derived dendritic cells. Stem Cells Dev. 2004;13:263–71. doi: 10.1089/154732804323099190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Corcione A, Benvenuto F, Ferretti E, et al. Human mesenchymal stem cells modulate B-cell functions. Blood. 2006;107:367–72. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-07-2657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Glennie S, Soeiro I, Dyson PJ, Lam EW, Dazzi F. Bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells induce division arrest anergy of activated T cells. Blood. 2005;105:2821–7. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-09-3696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Augello A, Tasso R, Negrini SM, et al. Bone marrow mesenchymal progenitor cells inhibit lymphocyte proliferation by activation of the programmed death 1 pathway. Eur J Immunol. 2005;35:1482–90. doi: 10.1002/eji.200425405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gupta N, Su X, Popov B, Lee JW, Serikov V, Matthay MA. Intrapulmonary delivery of bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells improves survival and attentuates endotoxin-induced acute lung injury in mice. J Immunol. 2007;179:1855–63. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.3.1855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nemeth K, Leelahavanichkul A, Yuen PS, et al. Bone marrow stromal cells attenuate sepsis via prostaglandin E(2)-dependent reprogramming of host macrophages to increase their interleukin-10 production. Nat Med. 2009;15:42–9. doi: 10.1038/nm.1905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Meisel R, Zibert A, Laryea M, Gobel U, Daubener W, Dilloo D. Human bone marrow stromal cells inhibit allogeneic T-cell responses by indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase-mediated tryptophan degradation. Blood. 2004;103:4619–21. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-11-3909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sato K, Ozaki K, Oh I, et al. Nitric oxide plays a critical role in suppression of T-cell proliferation by mesenchymal stem cells. Blood. 2007;109:228–34. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-02-002246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ren G, Zhang L, Zhao X, et al. Mesenchymal stem cell-mediated immunosuppression occurs via concerted action of chemokines and nitric oxide. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;2:141–50. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2007.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Aggarwal S, Pittenger MF. Human mesenchymal stem cells modulate allogeneic immune cell responses. Blood. 2005;105:1815–22. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-04-1559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Augello A, Tasso R, Negrini SM, Cancedda R, Pennesi G. Cell therapy using allogeneic bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells prevents tissue damage in collagen-induced arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56:1175–86. doi: 10.1002/art.22511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gerdoni E, Gallo B, Casazza S, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells effectively modulate pathogenic immune response in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Ann Neurol. 2007;61:219–27. doi: 10.1002/ana.21076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zappia E, Casazza S, Pedemonte E, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells ameliorate experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis inducing T-cell anergy. Blood. 2005;106:1755–61. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-04-1496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rafei M, Campeau PM, Aguilar-Mahecha A, et al. Mesenchymal stromal cells ameliorate experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis by inhibiting CD4 Th17 T cells in a CC chemokine ligand 2-dependent manner. J Immunol. 2009;182:5994–6002. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0803962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Madec AM, Mallone R, Afonso G, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells protect NOD mice from diabetes by inducing regulatory T cells. Diabetologia. 2009;52:1391–9. doi: 10.1007/s00125-009-1374-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fiorina P, Jurewicz M, Augello A, et al. Immunomodulatory function of bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells in experimental autoimmune type 1 diabetes. J Immunol. 2009;183:993–1004. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0900803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Robson MG, Walport MJ. Pathogenesis of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) Clin Exp Allergy. 2001;31:678–85. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2222.2001.01147.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Peister A, Mellad JA, Larson BL, Hall BM, Gibson LF, Prockop DJ. Adult stem cells from bone marrow (MSCs) isolated from different strains of inbred mice vary in surface epitopes, rates of proliferation, and differentiation potential. Blood. 2004;103:1662–8. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-09-3070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cassese G, Lindenau S, de Boer B, et al. Inflamed kidneys of NZB/W mice are a major site for the homeostasis of plasma cells. Eur J Immunol. 2001;31:2726–32. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200109)31:9<2726::aid-immu2726>3.0.co;2-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Uccelli A, Moretta L, Pistoia V. Immunoregulatory function of mesenchymal stem cells. Eur J Immunol. 2006;36:2566–73. doi: 10.1002/eji.200636416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ringden O, Uzunel M, Rasmusson I, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells for treatment of therapy-resistant graft-versus-host disease. Transplantation. 2006;81:1390–7. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000214462.63943.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sundin M, Ringden O, Sundberg B, Nava S, Gotherstrom C, Le Blanc K. No alloantibodies against mesenchymal stromal cells, but presence of anti-fetal calf serum antibodies, after transplantation in allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell recipients. Haematologica. 2007;92:1208–15. doi: 10.3324/haematol.11446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sun LY, Zhang HY, Feng XB, Hou YY, Lu LW, Fan LM. Abnormality of bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus. 2007;16:121–8. doi: 10.1177/0961203306075793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.El-Badri NS, Hakki A, Ferrari A, Shamekh R, Good RA. Autoimmune disease: is it a disorder of the microenvironment? Immunol Res. 2008;41:79–86. doi: 10.1007/s12026-007-0053-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cassese G, Arce S, Hauser AE, et al. Plasma cell survival is mediated by synergistic effects of cytokines and adhesion-dependent signals. J Immunol. 2003;171:1684–90. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.4.1684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Uccelli A, Moretta L, Pistoia V. Mesenchymal stem cells in health and disease. Nat Rev. 2008;8:726–36. doi: 10.1038/nri2395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Uccelli A, Pistoia V, Moretta L. Mesenchymal stem cells: a new strategy for immunosuppression? Trends Immunol. 2007;28:219–26. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2007.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Slifka MK, Matloubian M, Ahmed R. Bone marrow is a major site of long-term antibody production after acute viral infection. J Virol. 1995;69:1895–902. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.3.1895-1902.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Manz RA, Thiel A, Radbruch A. Lifetime of plasma cells in the bone marrow. Nature. 1997;388:133–4. doi: 10.1038/40540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Slifka MK, Antia R, Whitmire JK, Ahmed R. Humoral immunity due to long-lived plasma cells. Immunity. 1998;8:363–72. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80541-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Minges Wols HA, Underhill GH, Kansas GS, Witte PL. The role of bone marrow-derived stromal cells in the maintenance of plasma cell longevity. J Immunol. 2002;169:4213–21. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.8.4213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Devine SM, Bartholomew AM, Mahmud N, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells are capable of homing to the bone marrow of non-human primates following systemic infusion. Exp Hematol. 2001;29:244–55. doi: 10.1016/s0301-472x(00)00635-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rombouts WJ, Ploemacher RE. Primary murine MSC show highly efficient homing to the bone marrow but lose homing ability following culture. Leukemia. 2003;17:160–70. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2402763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Belema-Bedada F, Uchida S, Martire A, Kostin S, Braun T. Efficient homing of multipotent adult mesenchymal stem cells depends on FROUNT-mediated clustering of CCR2. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;2:566–75. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Traggiai E, Volpi S, Schena F, et al. Bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells induce both polyclonal expansion and differentiation of B cells isolated from healthy donors and systemic lupus erythematosus patients. Stem Cells. 2008;26:562–9. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2007-0528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rasmusson I, Le Blanc K, Sundberg B, Ringden O. Mesenchymal stem cells stimulate antibody secretion in human B cells. Scand J Immunol. 2007;65:336–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3083.2007.01905.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kawano MM, Mihara K, Huang N, Tsujimoto T, Kuramoto A. Differentiation of early plasma cells on bone marrow stromal cells requires interleukin-6 for escaping from apoptosis. Blood. 1995;85:487–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Roldan E, Brieva JA. Terminal differentiation of human bone marrow cells capable of spontaneous and high-rate immunoglobulin secretion: role of bone marrow stromal cells and interleukin 6. Eur J Immunol. 1991;21:2671–7. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830211105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Deng W, Han Q, Liao L, You S, Deng H, Zhao RC. Effects of allogeneic bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells on T and B lymphocytes from BXSB mice. DNA Cell Biol. 2005;24:458–63. doi: 10.1089/dna.2005.24.458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rafei M, Hsieh J, Fortier S, et al. Mesenchymal stromal cell-derived CCL2 suppresses plasma cell immunoglobulin production via STAT3 inactivation and PAX5 induction. Blood. 2008;112:4991–8. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-07-166892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Melchers F, Haasner D, Streb M, Rolink A. B-lymphocyte lineage-committed, IL-7 and stroma cell-reactive progenitors and precursors, and their differentiation to B cells. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1992;323:111–17. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-3396-2_14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Chomarat P, Banchereau J. Interleukin-4 and interleukin-13: their similarities and discrepancies. Int Rev Immunol. 1998;17:1–52. doi: 10.3109/08830189809084486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hauser AE, Debes GF, Arce S, et al. Chemotactic responsiveness toward ligands for CXCR3 and CXCR4 is regulated on plasma blasts during the time course of a memory immune response. J Immunol. 2002;169:1277–82. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.3.1277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lentzsch S, Gries M, Janz M, Bargou R, Dorken B, Mapara MY. Macrophage inflammatory protein 1-alpha (MIP-1 alpha) triggers migration and signaling cascades mediating survival and proliferation in multiple myeloma (MM) cells. Blood. 2003;101:3568–73. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-08-2383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tyndall A, Pistoia V. Mesenchymal stem cells combat sepsis. Nat Med. 2009;15:18–20. doi: 10.1038/nm0109-18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]