Abstract

We describe the clinical scenario of a young male with history of non ulcer dyspepsia who had endoscopic evidence of gastric polyposis in antral area. The polyps disappeared four months after proton pump inhibitors were stopped. Proton pump inhibitors have been linked to gastric fundal polyposis and not antral gland polyposis. This is the first report originating from an Asian country describing antral gland polyposis (AGPs) in a patient on long-term PPI therapy with no evidence of Helicobacter pylori. A case report with brief review is presented.

Keywords: proton pump inhibitors, hyperplastic gastric polyps, antral gland polyps, Helicobacter pylori

Abstract

Es wird der Fall eines jungen Mannes berichtet, bei dem endoskopisch eine Polyposis des Magens im antralen Bereich nachgewiesen wurde.

Die Polyposis verschwand vier Monate nach Absetzen der Therapie mit einem Protonenpumpenhemmer. Die Wirkung von Protonenpumpenhemmern auf die Entstehung von Polypen im Fundus ist beschrieben, nicht jedoch im antralen Bereich.

Dies ist der erste Bericht aus einem asiatischen Land über eine Magen-Polypose im antralen Bereich, aufgetreten nach einer Langzeittherapie mit Protonenpumpenhemmern. Eine Infektion mit Helicobacter pylori war nicht nachweisbar, ebenso fehlten Ulzerationen.

Introduction

Fundic gland polyps are now commonly recognised during endoscopy and their occurrence is attributed to prolonged proton pump inhibitor (PPI) therapy [1]. These polyps are benign, often multiple and are usually detected in gastric body and fundus. However, the polyps in antral area are often attributed to infection with H. pylori [2]. We observed that our patient had no evidence of H. pylori infection and had polyps in antral area. These polyps disappeared four months after stopping PPI therapy establishing a cause and effect relationship. This case report reflects the diffuse effect of PPI therapy in causing antral polyposis.

Case description

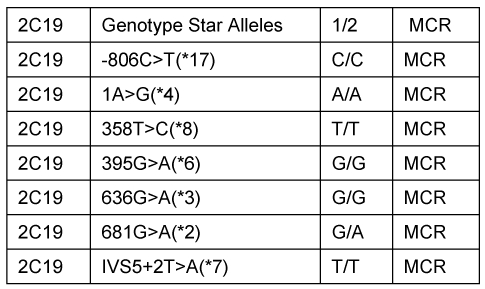

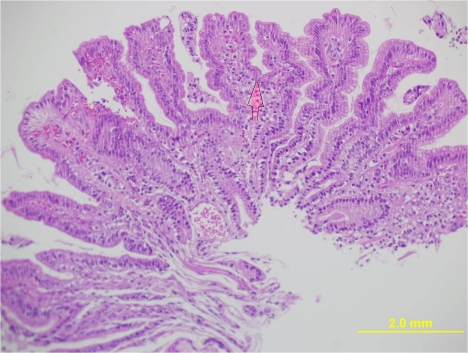

A 30 year old male presented to our clinic with history of on and off epigastric pain of 4 years duration without any alarming symptoms. The patient had no history of offending drug intake. He had been taking proton pump inhibitors Tab. Esomeprazole 20 mg twice daily continuously for 4 years with partial relief. He has been a non smoker and denied any drug abuse or alcohol intake. His systemic examination was unremarkable. He was evaluated on outpatient basis. He had haemoglobin of 14 g/dl with normal leucocytic count and normal platelet count. He had normal liver and kidney function tests. Serum amylase was within normal limits. Abdominal ultrasound showed a normal size of the liver with its normal echo texture. There were no gall stones, the common bile duct was normal and other abdominal viscera were also normal. The patient underwent upper gastrointestinal (GI) endoscopy which revealed a normal esophagus and a small hiatal hernia. There were multiple polyps in the antral area, each around 1 cm (Figure 1 (Fig. 1)). A biopsy was taken from these polyps and a Campylobacter-like organism (CLO) test was also done. The patient's biopsy (Figure 2 (Fig. 2)) revealed evidence of chronic gastritis with no H. pylori activity. The polyp was adenomatous with no features of malignancy. His serology for H. pylori was negative. The patient had a normal colonscopic examination and familial polyposis was ruled out.

Figure 1. Endoscopy showing multiple polyps in the antral area of the stomach.

Figure 2. Histology of the polyp.

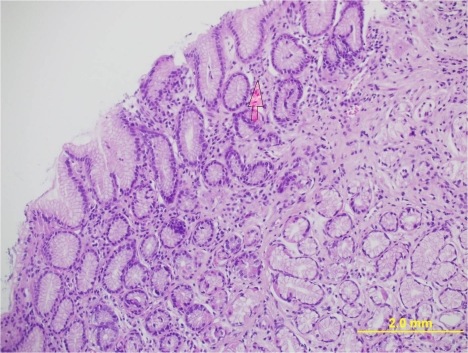

Proton pump inhibitors were stopped and upper GI endoscopy was repeated after 4 months (Figure 3 (Fig. 3)). There was almost disappearance of the antral polypoidal lesions. Repeated histology of the antral area showed complete regression of the polyp with mild gastritis and no H. pylori (Figure 4 (Fig. 4)). No H. pylori was grown after culture. The patient was given reassurance and symptomatic treatment. He is doing well and is following our clinic for 6 months now. The polypoid lesions were attributed to prolonged PPI usage and a CYP gene analysis (Table 1 (Tab. 1)) was done. The index case was found to have one copy of the gene encoding enzyme with normal activity and another copy coding for inactive enzyme.

Figure 3. Disappearance of the polyps after stopping PPI therapy.

Figure 4. Histology of the antrum, no polyps and no H. pylori seen.

Table 1. CYP2C19 sequence genotype of the index case.

Discussion

The relative prevalence of fundic gland polyps on routine endoscopy has increased in recent years. An American study [3] of upper gastroscopic examinations over one year period in 120,000 patients reported increased prevalence of gastric polyps higher than earlier reports. This was most likely because of the widespread use of proton pump inhibitors. In the same study, authors observed that H. pylori- and atrophy-associated polyps, including adenomas, were less common than in earlier series. Antral polyposis is often attributed to H. pylori infection, however the index case had no serological or histological evidence of H. pylori and responded to stoppage of PPI therapy. Studies [2] have shown that there is regression of gastric polyposis when H. pylori is eradicated. This implies that patients with H. pylori infection must be treated before embarking on more invasive treatments in gastric polyposis as often these are multiple. Our patient had polyposis in antral area clearly due to prolonged PPI therapy and the patient's polyps disappeared after PPI were stopped. Proton-pump inhibitors have remained central to the management of acid-suppression disorders for more than two decades now and are unchallenged with regard to their efficacy and popularity among doctors and patients [4]. Side effects of PPI therapy include reversible hypergastrinemia, enterochromaffin-like hyperplasia, and possibly acceleration of atrophic gastritis in the gastric corpus in patients with H. pylori infection. Studies have shown that long-term proton pump inhibitor use is associated with an up to fourfold increase in the risk of fundic gland polyps. The risk of dysplasia is negligible in gastric polyposis due to PPI use and there is no association of gastric polyposis with neoplasia [5]. Aetiologically, these polyps seem to arise because of parietal cell hyperplasia and parietal cell protrusions resulting from acid suppression [6]. The issue of duration of therapy leading to gastric polyposis was addressed by Allay et al. [7]. The authors observed that the only independent predictor of gastric polyp development was a duration of PPI therapy greater than 48 months. Increased dosage of therapy in contrast had no significant impact on the development of gastric polyposis [7]. It was of interest to determine the genotype of CYP2C19, the principal enzyme in PPI metabolism. The rare carriers of the homozygous deficiency show an about tenfold higher exposure of PPIs following normal doses than those patients who are homozygous active. Our patient's CYP gene sequencing revealed that he had one copy of the genes encoding normal enzyme activity and the other copy encoding an inactive enzyme. He was thus an intermediate metabolizer of the drug (Tab. Esomeprazole). This may have led to increased levels for prolonged periods and subsequent polyposis in antral area. All our efforts to correlate any association of these polyps in the index case with H. pylori were non contributory, even H.pylori culture was negative. Endoscopists need to be familiar with these findings. All efforts should be done to rule out neoplastic lesion in a polypoid gastric lesion and a careful follow up seems mandatory. We documented regression of these polyps following stoppage of PPI therapy like in other studies [8]. Long term of PPI usage is difficult to define. Studies have shown that most of the patients do not require prolonged PPI therapy and thus there is always need to rationalise their treatment. On demand therapy has been shown to be cost effective and should be considered in most patients [9].

Conclusion

Antral gastric polyps may be encountered during endoscopy in patients taking PPI therapy for prolonged periods. Efforts to eradicate H. pylori and trial of stopping PPI therapy may be warranted before subjecting these patients to more invasive procedures. However, follow up endoscopy to document the regression cannot be underestimated in these gastric lesions.

Notes

Conflicts of interest

None declared.

References

- 1.Hongo M, Fujimoto K Gastric Polyps Study Group. Incidence and risk factor of fundic gland polyp and hyperplastic polyp in long-term proton pump inhibitor therapy: a prospective study in Japan. J Gastroenterol. 2010;45(6):618–624. doi: 10.1007/s00535-010-0207-7. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00535-010-0207-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ji F, Wang ZW, Ning JW, Wang QY, Chen JY, Li YM. Effect of drug treatment on hyperplastic gastric polyps infected with Helicobacter pylori: a randomized, controlled trial. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12(11):1770–1773. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i11.1770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carmack SW, Genta RM, Schuler CM, Saboorian MH. The current spectrum of gastric polyps: a 1-year national study of over 120,000 patients. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104(6):1524–1532. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.139. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/ajg.2009.139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Freeman HJ. Proton pump inhibitors and an emerging epidemic of gastric fundic gland polyposis. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14(9):1318–1320. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.1318. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.14.1318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Genta RM, Schuler CM, Robiou CI, Lash RH. No association between gastric fundic gland polyps and gastrointestinal neoplasia in a study of over 100,000 patients. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7(8):849–854. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2009.05.015. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cgh.2009.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jalving M, Koornstra JJ, Wesseling J, Boezen HM, De Jong S, Kleibeuker JH. Increased risk of fundic gland polyps during long-term proton pump inhibitor therapy. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006;24(9):1341–1348. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2006.03127.x. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2036.2006.03127.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ally MR, Veerappan GR, Maydonovitch CL, Duncan TJ, Perry JL, Osgard EM, Wong RK. Chronic proton pump inhibitor therapy associated with increased development of fundic gland polyps. Dig Dis Sci. 2009;54(12):2617–2622. doi: 10.1007/s10620-009-0993-z. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10620-009-0993-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Huguet JM, Ruiz L, Ortí E, Luján M, Sempere J, Medina E. Poliposis gastrica secundaria a tratamiento con inhibidores de la bomba de protones. [Gastric polyposis due to treatment with proton pump inhibitors]. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;32(2):88–91. doi: 10.1016/j.gastrohep.2008.09.008. (Ger). Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.gastrohep.2008.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Raghunath AS, O'Morain C, McLoughlin RC. Review article: the long-term use of proton-pump inhibitors. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005;22 Suppl 1:55–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2005.02611.x. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2036.2005.02611.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]