Abstract

Until recently children with autism spectrum disorders (ASD) were rarely diagnosed before the age of 3 to 4 years. But a major thrust of current research has been to lower the age of identification, due in part to evidence supporting the effectiveness of early intervention. Late talkers -- toddlers who appear to be developing normally but do not begin speaking, acquire words very slowly, and do not begin combining words at the typical ages --are also typically seen in their second year or early in the third year of life. This report presents the findings of a comparison of toddlers who received clinical diagnoses of ASD and those who were clinically diagnosed as DLD in order to examine the patterns of behavior in the second and third years of life in these two groups. Findings suggest that, when matched on expressive language level, toddlers with ASD and DLD are similar, and less skilled than toddlers with TD, in their use of gaze to regulate interactions, their ability to share emotions with others, to engage in back-and-forth interactions, their rate of communication, and the range of sounds and words produced. The children with DLD were similar to those with TD, and higher than those with ASD, in terms of their nonverbal cognitive skills, use of gestures to communicate, use of pretend play, and ability to respond to language. Children with DLD did show some weaknesses in interpersonal skills -- such as sharing affect, using gaze, and initiating communication. However, their ability to engage in pretend play, use gestures to communicate and respond to language are sufficient to differentiate them from age-mates with ASD. The clinical implications of these findings are discussed.

Until recently children with autism spectrum disorders (ASD) were rarely diagnosed before the age of 3 to 4 years, (Chakrabarti & Fombonne, 2001; Fombonne, 2005; Charman & Baird, 2002; Filipek, Accardo, Baranek, Cook, Dawson, Gordon, et al., 1999). But a major thrust of current research has been to lower the age of identification, due in part to evidence supporting the effectiveness of early intervention (National Research Council, 2001; Rogers, 2006; Stahmer, Ingersoll, & Koegel, 2004). Recent research suggests of that clinical diagnosis of autism can be reliably assigned in the second or third year, and shows at least short-term stability (Matson, Wilkins, & Gonzales, 2008) when conferred by an team of experienced clinicians (Charman et al., 2005; Chawarska et al., 2007; Cox et al., 1999; Eaves & Ho, 2004; Lord, 1995; Lord, Risi, & DiLavore, 2006, Stone et al., 1999; Turner, Stone, Pozdol, & Coonrod, 2006; Wetherby et al., 2004).

Late talkers are also typically seen in their second year or early in the third year of life. These are children who appear to be developing normally, but do not begin speaking, acquire words very slowly, and do not begin combining words at the typical ages. Failure to begin speaking, or to acquire words and word combinations, is the most common presenting problem in young children (Toppleberg & Shapiro, 2000), and for those with very limited communication skills, it can be difficult to differentiate between ASD and those with a more circumscribed delay in language development (DLD). In this paper, we will review evidence derived from studies of toddlers who present with poor communication and social skills and examine their profiles at the two-year level for clues about how to distinguish these two syndromes in a very young child.

Studies done in the 1970s (e.g., Bartok, Rutter, & Cox, 1975) that investigated differences between school-aged children with ASD and those with significant language impairments reported that boys with ASD and DLD showed similar nonverbal abilities and similar levels of grammatical development. However, the boys with ASD had more severe receptive language deficits; more deviant language behaviors, such as echolalia; more difficulties in nonverbal modalities of communication, such as gesture; and more deficits in pragmatic uses of language. These differences have served as the criteria for making differential diagnoses of ASD from DLD since that time. However, there have been few empirical data to support the use of these distinctions at early ages. We have recently completed a study of toddlers with ASD who were followed to the age of four and contrasted to children with typical and delayed development. In this paper, we present the findings of a comparison of toddlers who received clinical diagnoses of ASD and those who were clinically diagnosed as DLD in order to examine the patterns of behavior in the second and third years of life in these two groups.

Subjects in these studies were referred for suspicion of ASD (n=174) or Developmental Delay (DD). In this report, we will focus on a relatively small subset of the DD children who had nonverbal developmental levels within the normal range, but had specific delays in language development (n=27). A contrast group of 171 children with typical development (TD), matched to the other groups on age, was also included. All these participants were between the ages of 16 and 34 months of age, and there were no differences among the groups in terms of their birth or medical histories. They had no known genetic syndromes or visual or hearing disorders. Participants were assigned to diagnostic group by means of extensive evaluations (See Table 1) that included standardized testing, structured behavioral observation, and extensive parent reports gathered through semi-structured interviews and questionnaires. Diagnoses were based on DSM-IV guidelines (APA, 1994), and arrived at by consensus between two experienced clinicians, one a speech-language pathologist and one a psychologist. Diagnosis was made on the basis of informed clinical judgment following interaction with the child, formal testing, and review of parent reports and records. The Autism Diagnostic Observation Scale-Module 1 (ADOS; Lord et al., 2000) and the Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised (ADI-R; Lord, Rutter, & Conture, 1994) were also administered to children in the ASD and DLD groups. Clinicians making diagnostic assignments had access to these results, but did not use them exclusively for making diagnostic decisions.

Table 1.

Assessment Procedures

| Area Assessed | Reference | |

|---|---|---|

| Direct Procedures | ||

| Communication and Symbolic Behavior Scales-DP | Social abilities Speech Symbolic behavior |

Wetherby & Prizant, 2003 |

| Mullen Scales of Early Learning | Visual Reception Fine & Gross Motor Expressive Language Receptive Language |

Mullen, 1995 |

| Autism Diagnostic Observation Scale-Module 1 | Social abilities Communication Imagination Repetitive Behaviors |

Lord et al., 2000 |

| Interview Measures | ||

| Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales | Communication Socialization Daily Living Skills Motor Skills |

Sparrow, Balla, & Cicchetti, 1984 |

| Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised | Social abilities Communication Repetitive Behaviors |

Lord, Rutter, & Conture, 1994 |

For children initially diagnosed as having ASD, all retained this diagnosis at follow-up evaluation, when they were approximately four years of age. For the children with DLD, all but four retained a diagnosis of DLD at age four. The four children who were no longer considered DLD at follow-up were judged to have moved within the normal range. Children with typical development were not seen for follow-up.

As Table 2 shows, most participants in all groups were male. Average age was approximately 2 years at intake. Analysis of Variance revealed that nonverbal abilities among the groups at this time, as measured by the Visual Reception and Fine Motor Scales of the Mullen Scales of Early Learning (Mullen, 1995) were significantly different; the group with a clinical diagnosis of ASD functioned below the average range and significantly lower than those assigned to the DLD or TD groups, who scored within the normal range on the Mullen. Expressive language skills as measured by both parent report of expressive vocabulary size on the MacArthur-Bates Communicative Development Inventory (Fensen et al., 2003) and by parent interviews on adaptive communication on the Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales (Sparrow, Balla, & Cicchetti, 1984), were not significantly different between the ASD and DLD groups; both were significantly lower in expressive skills that toddlers with TD.

Table 2.

Group Characteristics

| ASD | DLD | TD | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (yrs.) | 2.3 (.61)1 | 1.9 (.74)2 | 1.9 (.78)2 |

| % Male | 801 | 672 | 602 |

| Mullen VRa T | 34.8 (13.5)1 | 49.6 (12.2)2 | 53.2 (11.9)2 |

| Mullen FMb T | 31.3 (12.6)1 | 43.96 (9.9)2 | 50.1 (9.5)2 |

| CDI EVc | 66 (98)1 | 76 (104)1 | 175 (145)2 |

| Vld. Com. AEd (yrs.) | 1.3 (.64)1 | 1.4 (.58)1 | 2.1 (.87) 2 |

Values with differing superscripts are significantly different (p<.05)

Mullen Scales of Early Learning (Mullen, 1995) Visual Reception T-score

Mullen Scales of Early Learning (Mullen, 1995) Fine Motor T-score

MacArthur-Bates (Fensen et al., 2003) Communicative Development Inventory Expressive Vocabulary

Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales (Sparrow, Balla, & Cichetti, 1984) Communication Scale Age-Equivalent Score

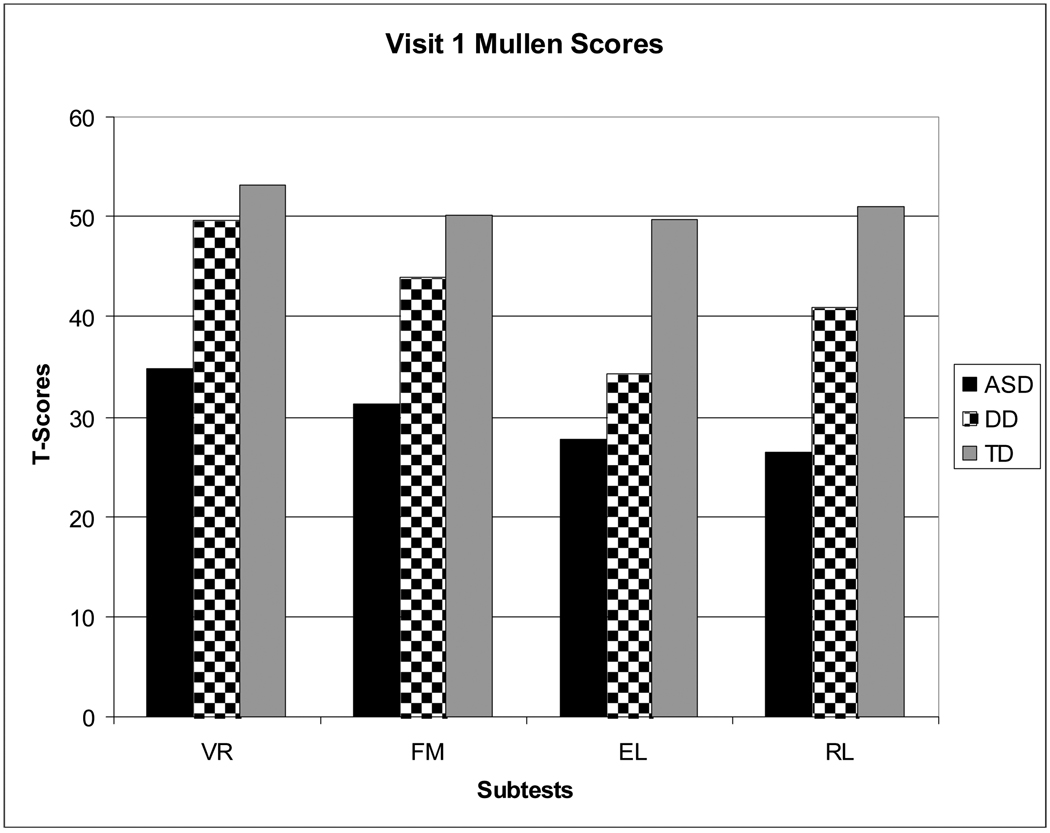

When we compared the standard testing profiles of the groups on the Mullen Scales of Early Learning (Mullen, 1995), Analysis of Variance showed that children with ASD differed from age-mates with DLD and TD not only on nonverbal skills and expressive language (EL), but on receptive language (RL), as well (See Figure 1). In fact, toddlers with ASD scored lower on the receptive scale of the Mullen than they did on the expressive scale. Children with ASD were significantly lower than those with DLD on both expressive and receptive scores; those with DLD were significantly lower on both these measures than those with TD.

Figure 1.

Scores for Three Groups on Mullen Scales of Early Learning (Mullen, 1995)

Key:

VR: Visual reception

FM: Fine motor

EL: Expressive language

RL: Receptive language

ASD: Autism spectrum disorder

DD: Developmental language delay

TD: Typical development

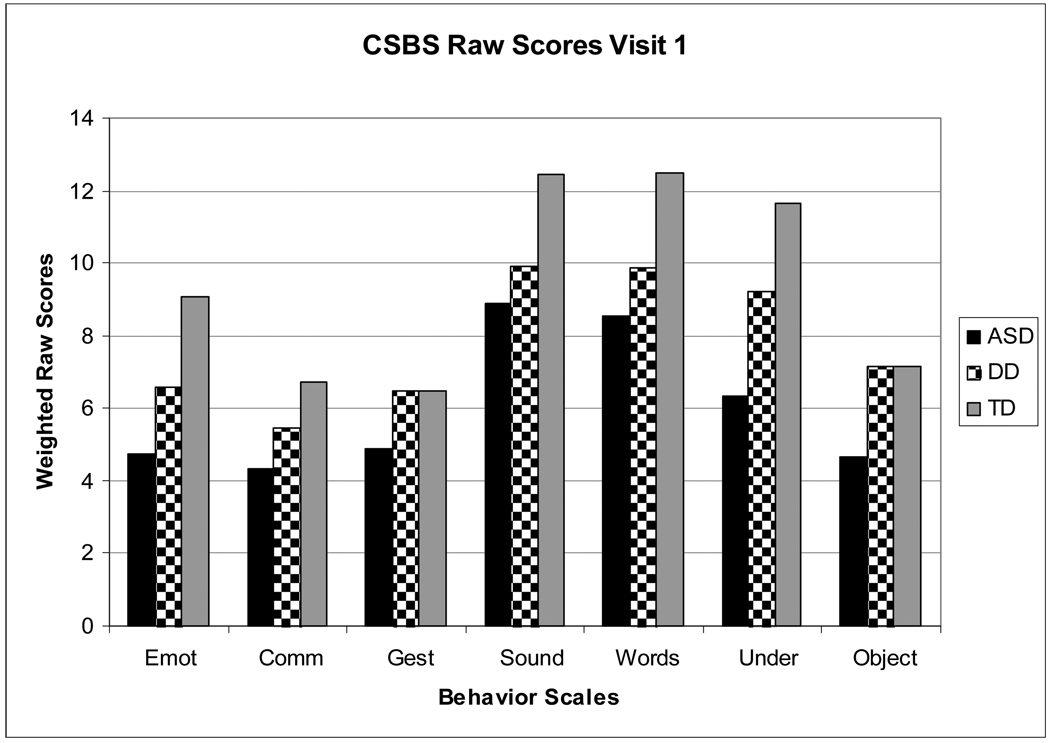

We looked, too, at a range of communication behaviors measured on the Behavioral Sample of the Communication and Symbolic Behavior Scales (Wetherby & Prizant, 2003). These are displayed in Figure 2. Analysis of Variance revealed that children with ASD and DLD earned similar scores on measures of the use of gaze, sharing of emotion and reciprocity, as well as on the production of sounds and words, and the expression of communicative acts. Both groups were significantly lower than toddlers with TD on all these measures, except for the number of communicative acts expressed, where the DLD group was not significantly different from either ASD or TD. The DLD group scored higher than ASD on the use of gestures, understanding of language and use of objects in pretend play schemes. On all these measures, the DLD group was not significantly different from the TD.

Figure 2.

Scores for Three Groups on Communication and Symbolic Behavior Scales (Wetherby & Prizant, 2003).

Key:

Emot: Emotion, Gaze, and Reciprocity

Comm: Communication

Gest: Gesture use

Sound: Sounds produced

Word: Words used

Under: Understanding of single words

Object: Use of objects in play schemes

ASD: Autism spectrum disorder

DD: Developmental language delay

TD: Typical development

These findings suggest that, when matched on expressive language level, toddlers with ASD and DLD are similar, and less skilled than toddlers with TD, in their use of gaze to regulate interactions, their ability to share emotions with others, to engage in back-and-forth interactions, their rate of communication, and the range of sounds and words produced. The children with DLD, however, were significantly different from toddlers with ASD, and similar to those with TD, in terms of their nonverbal cognitive skills, use of gestures to communicate, use of pretend play, and ability to respond to language. Perhaps contrary to expectations, these findings indicate that children with DLD do show some weaknesses in interpersonal skills -- such as sharing affect, using gaze, and initiating communication -- that go beyond the production of sounds and words, and may raise questions about their risk for ASD. However, their ability to engage in pretend play, use gestures to communicate and respond to language spoken to them provide differentiation from age-mates with ASD. Interestingly, two of these factors -- use of gestures and receptive language -- are the same areas in which Rutter el al., (1975) reported that school-aged children with ASD differed from those with significant language impairments. And although symbolic play deficits have been reported in toddlers with DLD (e.g., Rescorla & Goosens, 1992), our research suggests they are more similar to typical toddlers in this respect than they are to children with ASD.

Wetherby et al. also (2004) identified behaviors that differentiated two-year olds with ASD from those with either TD or non-specific DD. These included:

-

○

Lack of appropriate gaze

-

○

Lack of sharing of enjoyment and emotion with gaze

-

○

Failure to respond to name

-

○

Failure to coordinate gaze, gesture, facial expression and vocalization

-

○

Lack of expression of joint attention

-

○

Unusual vocalizations

-

○

Repetitive movements with body or objects

Our data suggest that children with both ASD and DLD may show some evidence of the first two of these, but the latter behaviors distinguish children with more circumscribed language delays from those with ASD in our cohort.

Clinical Implications

These findings suggest that care will need to be exercised in making diagnoses of ASD and DLD in toddlers with delayed communication skills. Like children with ASD, toddlers with DLD can appear less interested in interaction, less likely to use gaze to regulate communication, less able to engage in back-and-forth turn-taking, and less apt to initiate communication than typical age-mates. These features may raise concerns about risk for ASD. However, our data suggest that while they may show these weaknesses, as well as standard test scores in both expressive and receptive modes that are below the normal range, toddlers with DLD are more likely to respond to language in natural settings, such as the CSBS behavioral sample, as well as to show receptive language test scores that are at least as high, if not higher than, their expressive language level. Toddlers with ASD, on the other hand, are likely to show receptive language behaviors in both standard tests and structured play, that are worse than their expressive abilities would suggest. Toddlers with DLD are also more able than age-mates with ASD to spontaneously demonstrate some pretend play skills and to use some conventional gestures to communicate, even if these skills are not as advanced as their chronological age would predict. Table 3 summarizes these patterns.

Table 3.

Similarities and Differences: ASD and DLD Toddlers

| Non-Verbal Cognition | ASD<DLD |

| Use of gaze, reciprocity | ASD=DLD |

| Frequency of spontaneous communication | ASD=DLD |

| Expression of joint attentional intentions (Wetherby et al. 2004) | ASD<DLD |

| Expressive Language | ASD=DLD |

| Receptive Language | ASD<DLD |

| Use of Conventional Gestures | ASD<DLD |

| Spontaneous Pretend Play | ASD<DLD |

| Repetitive movements (Wetherby et al. 2004) | ASD>DLD1 |

| Unusual vocalizations (Wetherby et al. 2004) | ASD>DLD1 |

Children with ASD show more of these atypical behaviors than children with DLD

Definitive diagnosis of ASD in toddlers is often made on the basis of scores from the Autism Diagnostic Observation Scale (ADOS-G; Lord et al., 2000) and the Autism Diagnostic Interview (ADI-R (Lord, Rutter, & Conure, 1994), which are instruments that require large amounts of time to collect and extensive training to administer and interpret. These data suggest, however, that important information about diagnostic status in late-talking toddlers may be obtained by speech-language pathologists using instruments available in a typical clinic setting by examining a profile of strengths and weaknesses across a range of communicative behaviors. While it is certainly the case that making a diagnosis of ASD should involve a multidisciplinary team approach and employ autism-specific diagnostic instruments, speech-language pathologists seeing toddlers referred for delayed language development are often the first professionals to evaluate a very young child who is late to start talking, and may be in a setting that requires doing so without benefit of multidisciplinary input. When this is the case, data on empirically-derived profiles that characterize ASD and DLD can be helpful in deciding when to recommend more extensive and specialized assessment. The ability to make accurate diagnoses of children evidencing delays in the development of communication can lead to more focused, appropriate early intervention, which is known to contribute to improving outcome during the preschool years (Guralnick, 1997; National Research Council, 2001). Speech-language pathologists can contribute to this effort by being alert to signs that indicate a need for more extensive evaluation in toddlers with language delays.

Acknowledgements

Preparation of this paper was supported by Research Grant P01-03008 funded by the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH); the National Institute of Deafness and Communication Disorders R01 DC07129; MidCareer Development Award K24 HD045576 funded by NIDCD; NIMH Autism Center of Excellence grant # P50 MH81756; by the STAART Center grant U54 MH66494 funded by the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders (NIDCD), the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS), the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD), the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS), as well as by the National Alliance for Autism Research, and the Autism Speaks Foundation.

Continuing Education Questions

-

Toddlers with ASD and DLD are likely to perform similarly in terms of

- Nonverbal cognitive testing

- Rate of communication

- Use of gestures

- Pretend play

Answer: B

-

Toddlers with ASD and DLD are likely to show differences in

- Expressive language level

- Sounds produced

- Receptive language level

- Adaptive communication

Answer: C

-

Which children are likely to show receptive language scores that are lower than expressive scores?

- ASD

- DLD

- TD

- None of the above

Answer: A

-

Which of the following is a ‘red flag’ for ASD, according to Wetherby et al. (2004)?

- Lack of response to name

- Small expressive vocabulary

- Frequent expression of joint attention

- Delayed fine motor skills

Answer: A

-

Which of the following is an autism-specific diagnostic instrument?

- CSBS-DP

- Vineland

- Mullen

- ADI-R

Answer: D

Continuing Education Author background:

-

Rhea Paul, Ph.D., CCC-SLP

Southern Connecticut State University and Yale Child Study Center

Professor

Autism spectrum disorders, early expressive language disorders

-

Katyrzyna Chawarska, Ph.D.

Psychologist

Yale Child Study Center

Ass’t. Prof.

Autism spectrum disorders in infants and toddlers, visual perception

-

Fred R. Volkmar, M.D.

Child Psychiatrist

Yale Child Study Center

Director; Prof. of Pediatrics, Psychiatry, and Psychology

Autism spectrum disorders; diagnostic issues; psychopharmacology

References

- Bartak L, Rutter M, Cox A. A comparative study of infantile autism and specific developmental receptive language disorder. British Journal of Psychiatry. 1975;126:127–145. doi: 10.1192/bjp.126.2.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chakrabarti S, Fombonne E. Pervasive developmental disorders in preschool children. Jama: Journal of the American Medical Association. 2001;285(24):3093–3099. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.24.3093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charman T, Baird G. Practitioner review: Diagnosis of autism spectrum disorders in 2- and 3-year-old children. Journal of Child Psychology & Psychiatry & Allied Disciplines. 2002;43:289–305. doi: 10.1111/1469-7610.00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charman T, Taylor E, Drew A, Cockerill j, Brown, Barid G. Outcome at 7 years of children diagnosed with autism at age 2: predictive validity of assessments conducted at 2 and 3 years of age and pattern of symptom change over time. Journal of Child Psychology & Psychiatry. 2005;46:500–513. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00377.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chawarska K, Klin A, Paul R, Volkmar F. Autism spectrum disorder in the second year: Stability and change in syndrome expression. Journal of Child Psychology & Psychiatry. 2007;48:128–138. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2006.01685.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox A, Klein K, Charman T, Baird G, Baron-Cohen S, Swettenham J, et al. Autism spectrum disorders at 20 and 42 months of age: Stability of clinical and ADI-R diagnosis. Journal of Child Psychology & Psychiatry & Allied Disciplines. 1999;40:719–732. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eaves L, Ho H. The very early identification of autism: Outcome to 4 ½ – 5. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2004;34:367–378. doi: 10.1023/b:jadd.0000037414.33270.a8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fensen L, Dale P, Reznick S, Thal D, Bates E, Hartung J, Pethick S, Reilly J. MacArthur Communicative Developmental Inventories. Baltimore: Paul H. Brookes; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Filipek P, Accardo P, Baranek G, Cook E, Dawson G, Gordon B. The screening and diagnosis of autistic spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 1999;29:439–484. doi: 10.1023/a:1021943802493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fombonne E. Epidemiological studies of Pervasive Developmental Disorders. In: Volkmar F, Paul R, Klin A, editors. Handbook of autism and pervasive developmental disorders-3rd Ed-Vol. 1. N.Y: Wiley & Sons; 2005. pp. 42–69. [Google Scholar]

- Guralnick MJ. The effectiveness of early intervention. Baltimore, MD: Paul H. Brookes; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Lord C. Follow-up of two-year-olds referred for possible autism. Journal of Child Psychology & Psychiatry & Allied Disciplines. 1995;36(8):1365–1382. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1995.tb01669.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lord C, Risi S, DiLavore P. Autism from 2 to 9 years of age. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2006;63:694–701. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.6.694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lord C, Risi S, Lambrecht L, Cook EH, Leventhal BL, DiLavore PC, et al. The Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule--Generic: A standard measure of social and communication deficits associated with the spectrum of autism. Journal of Autism & Developmental Disorders. 2000;30(3):205–223. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lord C, Rutter M, Conture A. Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised: A revised version of a diagnostic interview for caregivers of individuals with possible pervasive developmental disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 1994;24:659–685. doi: 10.1007/BF02172145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matson J, Wilkins J, Gonzalez M. Early identification and diagnosis in autism spectrum disorders in young children and infants: How early is too early? Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders. 2008;2:75–84. [Google Scholar]

- Mullen E. Mullen scales of early learning: AGS Edition. Circle Pines, MN: AGS Publishing; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- National Research Council. Educating children with autism. Washington, DC: Author; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Rescorla L, Goossens M. Symbolic play development in toddlers with expressive specific language impairment. Journal of Speech and Hearing Research. 1992;35:1290–1302. doi: 10.1044/jshr.3506.1290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers S. Evidence-based intervention for language development in young children with autism. In: Charman T, Stone W, editors. Social and communication development in autism spectrum disorders: Early identification, diagnosis, and intervention. New York: Guilford; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Sparrow S, Balla D, Cicchetti DV. The Vineland Adapative Behavior Scales (Survey Form) Circle Pines, MN: American Guidance Service; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Stahmer A, Intersoll B, Koegel R. Inclusive programming for toddlers with autism spectrum disorders: Outcomes from a children's toddler school. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions. 2005;6:67–82. [Google Scholar]

- Stone W, Lee E, Ashford L, Brissie J, Hepburn S, Coonrod E, Weiss B. Can autism be diagnosed accurately in children under 3 years? Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 1999;40:219–226. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toppelberg CO, Shapiro T. Language Disorders: A 10-Year Research Update Review. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2000;39:143–152. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200002000-00011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner L, Stone W, Pozdol S, Coonrod E. Follow-up of children with autism spectrum disorders from age 2 to age 9. Autism. 2006;10:243–265. doi: 10.1177/1362361306063296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wetherby A, Prizant B. Communication and Symbolic Behavior Scales-Developmental Profile. Baltimore: Paul H. Brookes; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Wetherby A, Woods J, Allen L, Cleary J, Dickinson H, Lord C. Early indicators of autism spectrum disorders in the second year of life. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2004;34:473–493. doi: 10.1007/s10803-004-2544-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]