Abstract

Motivation: Short interfering RNA (siRNA)-induced RNA interference is an endogenous pathway in sequence-specific gene silencing. The potency of different siRNAs to inhibit a common target varies greatly and features affecting inhibition are of high current interest. The limited success in predicting siRNA potency being reported so far could originate in the small number and the heterogeneity of available datasets in addition to the knowledge-driven, empirical basis on which features thought to be affecting siRNA potency are often chosen. We attempt to overcome these problems by first constructing a meta-dataset of 6483 publicly available siRNAs (targeting mammalian mRNA), the largest to date, and then applying a Bayesian analysis which accommodates feature set uncertainty. A stochastic logistic regression-based algorithm is designed to explore a vast model space of 497 compositional, structural and thermodynamic features, identifying associations with siRNA potency.

Results: Our algorithm reveals a number of features associated with siRNA potency that are, to the best of our knowledge, either under reported in literature, such as anti-sense 5′ −3′ motif ‘UCU’, or not reported at all, such as the anti-sense 5′ -3′ motif ‘ACGA’. These findings should aid in improving future siRNA potency predictions and might offer further insights into the working of the RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC).

Contact: cholmes@stats.ox.ac.uk

Supplementary information: Supplementary data are available at Bioinformatics online.

1 INTRODUCTION

RNA interference (RNAi) is a post-transcriptional gene silencing (PTGS) mechanism which inhibits gene expression. It is mediated by double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) or by transcripts that form stem-loops (short hairpin RNA, shRNA).

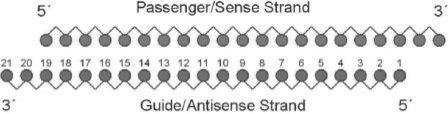

During the process of RNAi, dsRNA/shRNA is split by the Ribonuclease III enzyme Dicer into 19-nt dsRNA molecules with 2-nt 3′ -overhangs, named short interfering RNA (siRNA, depicted in Figure 1). The siRNA then interacts with the RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC), specifically with its catalytic component, the Argonaute protein. RISC-Argonaute separates the two strands of the siRNA molecule into the guide strand (anti-sense to the targeted mRNA), which is loaded into the Argonaute protein, and the passenger strand (sense to the targeted mRNA), which is released into the cytoplasm and subsequently degraded (Lodish et al., 2004). In a following step, the RISC–siRNA complex probes cytoplasmic mRNA molecules for sequence complementarity to the loaded siRNA guide strand. Matching mRNA molecules are cut around the center of the siRNA–mRNA interaction site (cleavage site) by the Argonaute protein, effectively inhibiting the expression of the respective gene product. Wang et al. have recently published a crystallographic structure of the complex, taken from an eubacterium (Wang et al., 2008).

Fig. 1.

Structure of short interfering RNA (siRNA). Both guide and passenger strands are displayed and the guide strand nucleotides are numbered in 5′ to 3′ direction.

Not long after its discovery, it was known that not all siRNAs are equally potent (Holen et al. 2002). The search for potent siRNAs and for features that could explain their silencing capabilities has since become the focus of numerous research groups in the field.

Initially, most groups conducted experiments on smaller sets of mRNAs. They measured the capability of different siRNA sequences to silence their respective gene products and tried to identify features that could be linked to the reported siRNA potency. Until recently, the focus was on compositional or thermodynamic features, both of which are sequence-based. Compositional features describe the occurrences of certain nucleotides at certain positions of the siRNA sequences, whereas thermodynamic features are concerned with binding free energies and stabilities of the sequences. A third group of features used in literature are structure-based ones (Shao et al., 2006, 2007; Vickers et al., 2003). These include secondary structure characteristics of both the siRNA and its mRNA target. According to Patzel et al., siRNAs with no defined secondary structure correlate with increased potency (Patzel et al., 2005). Moreover, one would expect target accessibility to be decisive for whether an otherwise well-designed siRNA can bind to its complementary part on the mRNA sequence (Ding et al., 2004). Researchers who incorporated mRNA characteristics in their feature set reported that, although they appear to be correlated with siRNA potency when no additional features were selected, they seemed to offer little to the predictive strength of their models, when added to an existing set of sequence-based features (Katoh and Suzuki, 2007; Peek, 2007). Others, however, did report correlation of site accessibility with siRNA potency (Shao et al., 2006).

Some researchers prefer to work on purpose-build datasets produced by them (Katoh and Suzuki, 2007; Reynolds et al., 2004; Shao et al., 2006; Ui-Tei et al., 2004), which are usually small and target only a few mRNAs. By contrast, others perform their analysis on combined data from heterogeneous sources (Holen, 2006; Matveeva et al., 2007; Saetrom, 2004; Shabalina et al., 2006; Vert et al., 2007). The latter is becoming increasingly popular, as the amount of publicly available data steadily increases. The large dataset by Huesken et al. (Huesken et al., 2005) can be seen as a landmark towards this direction.

A problem with studying heterogeneous datasets though is the variability in the biological methods employed, as well as in the information provided to the scientific community. As an example, earlier studies tended to employ 19-nt sequences (Ui-Tei et al., 2004), while more recent studies use 21-nt siRNA sequences, taking the 2-nt 3′ siRNA overhangs into account. These 2-nt overhangs appear to be correlated with siRNA potency (Huesken et al., 2005); however, this correlation cannot be tested on a 19-nt dataset. Matveeva et al. encounter this problem in their recent study (Matveeva et al., 2007), as they build two prediction models based on a 21-nt dataset, but can only test them on three 19-nt datasets.

Another problem encountered when combining data from heterogeneous sources is the lack of detailed information regarding the target sequence, such as which particular transcript was targeted and what the exact sequence of that transcript is. Such issues render the incorporation of structural mRNA information into a model challenging.

Having gathered the experimental data, a variety of statistical methods can be employed in an attempt to determine which features of a candidate siRNA sequence influence its potency. These include simple linear regression-based methods (Matveeva et al., 2007; Shabalina et al., 2006; Ui-Tei et al., 2004; Vert et al., 2007) as well as more complex methods like neural networks (Huesken et al., 2005; Shabalina et al., 2006), Euler graphs (Pancoska et al., 2004), Support Vector Machines (Ladunga, 2007; Peek, 2007; Saetrom, 2004; Teramoto et al., 2005), genetic programming (Saetrom, 2004) and disjunctive rule merging (Gong et al., 2008). With the performance of linear regression-based methods shown to be comparable to most of the more complex methods (Matveeva et al., 2007; Shabalina et al., 2006; Vert et al., 2007), linear regression has proven to be a reasonable choice, given its simplicity of concept and implementation and the interpretability of the results it produces. For these reasons, it was decided to be employed in this study.

We have investigated an approximate Bayesian Markov chain Monte Carlo feature selection algorithm using a Bayesian Information Criteria (BIC) (cf. Kass and Raftery, 1995) to approximate the Bayes factor for a logistic regression model on a large meta-dataset of 6483 siRNA's that we constructed employing the most widely used, publicly available datasets (we focus only on siRNAs that target mammalian mRNA). As far as the authors are aware this is the largest study of its kind to date. By following a purely data-driven approach, we hoped to confirm most of the recent findings, to resolve cases with contrasting evidence from different studies and to discover novel features that associate with siRNA potency.

A stochastic approach was considered essential, in order to efficiently explore the vast feature space of 497 compositional, thermodynamic and structural features that were put together to be tested for association with siRNAs potency. These covered most, if not all, of the features reported in recent studies, resulting in the most extensive set of features worked on so far. As a result, we present an efficient algorithm which succeeds in identifying novel features that significantly affect siRNA potency while performing comparably to most successful recent prediction methods (see Supplementary Material for more details). We then employ our algorithm to suggest 10 potent siRNAs for each of the human mRNA listings in the NCBI RefSeq database (Pruit et al., 2007; http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/RefSeq). These results can be found at our website.

2 METHODS

2.1 Consensus format for siRNA sequences

The following set of rules was chosen in this study, defining how siRNA sequences and the measurement of their respective silencing efficacy are presented:

siRNA sequences are stated as anti-sense sequences from 5′ to 3′ (Figure 1)

Potency (synonymous to efficiency and efficacy) refers to the ability of an siRNA to inhibit (synonymous to knock-down and down-regulate) a gene product

Product level refers to the percentage of the gene product remaining after siRNA-mediated RNA interference

Product levels of zero and one are assigned to fully potent and non-potent siRNAs, respectively

Only 19-nt siRNA sequences are employed in this study (3′ siRNA overhangs are neglected)

Compositional features are represented with the initial of the base followed by its position on the anti-sense strand, e.g. U7 means Uracil at nucleotide position 7 of the siRNA anti-sense strand.

2.2 Features

Four hundred and ninety-seven features have been included in our systematic study spanning position-dependent nucleotide preferences, GC content of the siRNA sequence, presence of 2-, 3- and 4-mer sequence motifs, presence of known innate inferon response-stimulating motifs, occurrence of palindromes, thermodynamic features and structural features of the siRNA. Most of the features that were tested in recent studies and found to be correlated with siRNA potency have been included in our feature set. In addition, the set was enriched by features that were not been tested before (e.g. tetranucleotide free energy differences). For a detailed description of each group of features and an exhaustive list of the features included in this study, please refer to the Supplementary Material.

2.3 Databases

We collected data from the online database siRecords (Ren et al., 2009; http://sirecords.umn.edu/siRecords) and from recently published datasets, which were either purpose-built (Katoh and Suzuki, 2007; Phipps et al., 2004) or collections of other, earlier published ones (Matveeva et al., 2007; Saetrom, 2004; Shabalina et al., 2006). In a pre-processing step, we limited our data to siRNA sequences targeting mammalian mRNA.

We focused at siRecords as it represents one of the largest resources of curated siRNA data, which is accessible to academic/non-commercial users by download (current release: 18 Aug 2008). Other online databases, such as HuSiDa (http://itb.biologie.hu-berlin.de/∼nebulus/sirna/index.htm) or siR (Reynolds2004, http://www.mpibpc.gwdg.de/abteilungen/100/105/sirna.html), are available and will be considered for inclusion into future versions of our dataset.

In our report, we refer to the combined datasets of Shabalina et al. (Shabalina et al., 2006) and Saetrom et al. (Saetrom, 2004) as SHA and SAE, respectively to highlight the fact that we obtained the data from the aforementioned sources. These datasets though are themselves a heterogeneous set of data produced by many different groups (Aza-Blanc et al., 2003; Giddings et al., 2000; Harboth et al., 2003; Holen et al., 2002; Hsieh et al., 2004; Jackson et al., 2003; Kawasaki et al., 2003; Khvorova et al., 2003; Kumar et al., 2003; Reynolds et al., 2004; Ui-Tei et al., 2004; Vickers et al., 2003). A summary, highlighting the key features of each dataset and a reference for each, is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Overview of datasets employed in this study

| Dataset | Size | Reference | Strand Format | SiRNA concentration | Potency | Also contained in |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| siRecords (SIR) | 2881 | Ren et al. (2009) | S | Variablea | Four classes | – |

| Sloan–Kettering (SLO) | 601 | Jagla et al. (2005) | AS | 100 nM | [0, 1] | – |

| Isis (ISI) | 67 | Vickers et al. (2003) | AS | 100 nM | [0, 1] | SHA, SAE, SIR |

| Novartis (NOV) | 2431 | Huesken et al. (2005) | AS | 50 nM | [0, 1] | – |

| Katoh (KAT) | 702 | Katoh and Suzuki (2007) | S | 10/25 nM | [0, 1]b | – |

| Shabalina (SHA) | 653 | Shabalina et al. (2006)c | AS | Variablea | [0, 1] | SAE, SIR |

| Saetrom (SAE) | 537 | Saetrom (2004)c | AS | Variablea | [0, 1] | – |

| Phipps (PHI) | 26 | Phipps et al. (2004) | S | 300 nM | [0, 1]b | SIR |

| Amgen–Dharmacon (AMG) | 239 | Reynolds et al. (2004) Khvorova et al. (2003) | AS | 100 nM | [0, 1] | SHA, SAE, SIR |

The columns for dataset, size and reference refer to the name and abbreviation, the number of siRNA samples contained and the reference to the dataset, respectively. Strand format indicates which strand is reported in the original study: sense (S) or antisense (AS). In the next column the siRNA concentration, as reported in the respective study, is stated. Furthermore, potency is either reported in a continuous scale over [0, 1], where 0 represents fully potent and 1 non-potent or as discrete value, where samples are split into different potency classes.

aFor these datasets, siRNA data has been collected from various experiments, all at slightly different experimental condition, so a common value for siRNA concentration used cannot be stated.

bIn these datasets, potency was reported in a continuous scale over [0, 1], but fully potent entries were represented by 1, and non-potent by 0.

cFor these combined datasets, a reference list of the individual datasets they contain is given in the main article.

The task of combining data from heterogeneous sources into a single meta-analysis study is not straightforward. Two of the key problems are (i) the inconsistency in measuring and reporting siRNA potency (Jagla et al., 2005) and (ii) the fact that reported results might refer to either sense or antisense strand siRNA sequences, and the necessary transformation to make findings comparable might introduce errors (Leuschner et al., 2006). Both of these problems are addressed in detail in the Supplementary Material.

It should be highlighted that in studies which are not specifically aimed at assessing silencing efficacy of siRNA sequences and where candidate samples have been picked with the help of a design algorithm the reported siRNAs will not represent the full spectrum of possible sequences, eventually introducing a bias. Moreover, in such cases often only the potent siRNAs are reported, leading to over-representation of potent siRNAs over non-potent, as is the case for the siRecords (SIR) database. Combining data from various sources should aid in reducing these biases, allowing us to better explore the siRNA sequence state space.

Another issue to be taken into consideration for all siRNA potency studies is the concentration of siRNA used in the silencing experiment. It can be seen in Table 1 that the concentrations of siRNA employed in the various experiments vary. It is generally accepted that silencing efficiency will be compromised when using too low siRNA concentrations. On the other hand, too high concentrations can induce non-specific, off-target effects (Persengiev et al., 2004), which can be reduced, albeit not alleviated (Jackson2003b), by reducing the siRNA concentration. Even though some groups report very similar siRNA potencies for concentrations varying between 20–100 nM (Jackson et al., 2003; Semizarov et al., 2003), there appears to be no consensus on the optimal amount to use—a value, which might well be gene- and tissue-specific.

Although a breakdown of the data according to siRNA concentration employed in the study might have increased the power of our study, we decided not to pool our data due to the already small number of available siRNA samples (compared to the vast siRNA state space). Given that a slight concentration-specific difference in silencing efficiency is likely to exist in our dataset, we expect a small artificial increase in variance, which we deem unlikely to have any effect on the selection of the most important predictors.

Concentrations were not reported for the siRecords database. However, as will be shown in detail below, the leave-one-out approach followed by our algorithm yielded similar results qualitatively when SIR data was excluded from the training set. This could mean that the siRNA concentrations employed to derive most of the entries in SIR are similar to those in the other datasets, or that the feature selection process is not significantly affected by difference in concentrations amongst datasets, or both. A proof of this statement will be left to a follow-up study which will hopefully be conducted in the light of a larger available dataset and more complete data.

Starting with our pool of nine datasets (SLO, ISI, AMG, NOV, KAT, SHA, SAE, SIR, PHI), all datasets were first checked for uniqueness and then cross-checked against each other to retrieve a set of unique and independent datasets. ISI, AMG and SHA were found to be fully contained in SIR and SAE, they were dropped from further investigation, leaving the following datasets to be included in this study:

SLO: SLO complete (601 samples)

NOV: NOV complete (2431 sequences)

KAT: KAT complete (702 sequences)

SIR: SIR without entries from ISI, AMG, KAT, SHA, PHI and SAE (2240 sequences)

SAE: unique entries of SHA, PHI and SAE (509 sequences)

The resulting ratio of potent to non-potent entries for each database is given in Table 2. The combined set has a ratio of approximately 1:1.

Table 2.

Ratio of potent to non-potent entries contained in the datasets

| Dataset | Size | Potent | Non-potent | Ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SLO | 601 | 179 | 422 | 0.4242 |

| NOV | 2431 | 1222 | 1209 | 1.0108 |

| KAT | 702 | 176 | 526 | 0.3346 |

| SAE | 509 | 197 | 312 | 0.6314 |

| SIR | 2240 | 1577 | 663 | 2.3786 |

| Total | 6438 | 3351 | 3132 | 1.067 |

The full dataset for our study contained 6483 unique and experimentally validated 19nt siRNA sequences in anti-sense description. To classify siRNA entries from the various datasets in terms of product levels, we employed an arbitrary, but commonly used, threshold of 0.3. Product levels <0.3 and ≥0.3 indicated potent and non-potent siRNA, respectively. This threshold is only employed for initial classification; the actual potency threshold changes to satisfy the 95% specificity criterion, as explained in detail in the Supplementary Material.

2.4 Algorithm

A strictly data-driven approach was followed for the model selection with no a priori assumptions about biological significance or relative importance of features were incorporated into our model at any time. All features were considered equally likely to affect siRNA potency.

Our model exploration algorithm generated models by sampling features from their posterior probability given the data, through the stochastic selection from the 497-element feature set and calculating the respective logistic regression parameters for subsets of the features (see details below). Each generated model was a candidate for inclusion in the final model set, which was then used to make predictions of siRNA potency, in the form of remaining product levels after siRNA activity.

A BIC (Bayesian Information Criterion) scheme was employed as a probabilistic scoring measure. The BIC approximates for any feature set the log posterior probability under a Bayesian model (cf. Kass and Raftery, 1995) and is proportional to L−1/2p log n, where L is the maximum log-likelihood, n is the number of samples in the training set, and p the number of selected features. The BIC is an approximation to the Bayesian marginal likelihood which integrates out over uncertainty in parameter coefficient values. The Bayes marginal likelihood is known to contain a natural penalty against over-complex models and hence parsimonious models are preferred under this approach (cf. Bernardo and Smith, 2000). We use a Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) algorithm, employing the BIC as an approximation to the true marginal likelihood of any model, to generate models (or feature sets) in proportion to their posterior probability. MCMC is a generic approach to generating samples from a complex target distribution and is well suited to the task of variable set uncertainty (cf. Gelman et al., 2003)

Hence we probe the 497-dimensional feature space using a MCMC algorithm, as detailed below, from which we are able to characterize feature set relevance, (cf. Kass and Raftery, 1995; Kass and Wasserman, 1995; Raftery, 1995).

The algorithm starts from an initial feature set and evolves it over time in a stepwise manner, which is outlined in the following:

-

INITIAL STEP: An initial feature set is chosen and the respective BIC-weighted log-likelihood of the model, comprised by these features, is calculated. The feature list and the penalized log-likelihood are referred to as features_active and result_active in the following.

For each step one of the following is done with equal chance:- REMOVE: Randomly remove a feature from features_active

- ADD: Randomly add a feature to features_active

- SWAP: randomly add a feature to features_active while removing another feature at the same time

The modified feature list is then stored as features_proposed and the BIC of the new model is calculated and stored in result_proposed

- IF result_proposed > result_active (the proposed model performs better)

- Accept the proposed model

- features_proposed becomes features_active

- result_proposed becomes result_active

- ELSE (the proposed model performs worse)

- Calculate a measure of change between result_proposed and result_active as

- α=exp(result_proposed – result_active),

- Draw a random number from a unit distribution RAND∼U(0, 1).

- IF RAND ≤α,

- Accept the proposed model even though it performs worse than the active one

- features_proposed becomes features_active

- result_proposed becomes result_active

- ELSE

- Reject the proposed model

- features_active remains unchanged

- result_active remains unchanged

Store features_active in features_sets(i)

REPEAT steps 1, 2 for i=1,2,…,NRUNS

Skip the first NSKIP entries of features_sets(i) which represent the burn-in phase of the algorithm, containing more than average variations in the features selected.

Check the remaining features sets for unique feature sets and store them in unique_feature_sets. Store the number of percental appearance of each unique feature set in kMODEL

Calculate predictions for all of the unique models, each being defined by an entry in unique_feature_sets

- Weight each prediction according to the respective entry in kMODEL.

- Both unique_feature_sets and kMODEL contain NUNIQUE entries.

FINAL STEP: The final prediction of our Monte-Carlo algorithm is a kMODEL-weighted average of the predictions of the NUNIQUE models defined in unique_feature_sets.

The above scheme samples the feature sets according to their posterior probability measure Pr(feature set | data). This in turn means that multiple models with high predictive power are explored and, due to the employed model averaging, the predictive power of a large set of individual models is combined into one single prediction.

3 RESULTS

We ran our Bayesian Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) feature selection algorithm for 1 100 000 iterations—including a 100 000 iteration burn-in phase—starting three times with the Matveeva et al. Model2 (Matveeva et al., 2007) as initial feature set, and two more times with initial models composed of randomly picked features. For each initial model, we trained our algorithm on five different training datasets and then went on to test its performance on a test dataset. The training datasets for each of these runs were composed of four of our five datasets (SLO, NOV, KAT, SAE, SIR) and the remaining dataset was used as the test dataset (leave-one-out scheme). By using all five possible combinations, we arrived at a total of 25 runs (five initial models times five training/test dataset combinations), together representing 25 000 000 iterations of our algorithm.

The output of each of these 25 runs consisted of a list of percentile appearance of each of the 497 features during the 1 000 000 Bayesian MCMC iterations of the respective run. In a next step, all 25 lists retrieved from our runs were combined and the overall percentile occurrence of each feature in all 25 runs (representing 25 000 000 iterations of our algorithm) was calculated. A final list with the 19 features most dominant in all models generated by the Bayesian MCMC algorithm is depicted in the Table 3. These are features contained in more than 33% of the models generated in all 25 runs. This cut-off is arbitrary and was chosen so that the number of features selected by our algorithm matches that of the model against which we validated our results (Matveeva et al., 2007, cf. Supplementary Material). The results of the model, comprised of only these 19 features, compare favourably with the performance of the most recent algorithms, further validating our approach to feature selection (cf. Supplementary Material).

Table 3.

Percentile occurrences of the ‘UCU’ and ‘ACGA’ motifs

| Dataset | All datasets (%) | Excluding SIR (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Potent entries (all samples) | 51.7 | 41.5 |

| Potent entries (only samples containing ‘UCU’) | 60.1 | 49.4 |

| Potent entries (only samples containing ‘ACGA’) | 36.5 | 25.4 |

Comparison of percentile occurrences of the ‘UCU’ and ‘ACGA’ motifs in potent siRNA sequences for the case that all five of our datasets (SLO, NOV, KAT, SAE, SIR) are considered and the case that the SIR dataset is excluded.

By using varying initial models for our Bayesian MCMC algorithm, we ensured that no bias was present in our simulations. Furthermore, the fact that all runs of the algorithm—irrespectively of the initial feature set—lead to comparable results indicates that our algorithm converged. This is reinforced by the fact that the average model sizes do not change significantly between different runs (cf. Supplementary Material).

The fact that only thirteen of the 497 features were present in more than 50% of all Monte-Carlo generated models can be taken as an indicator of the complexity of the silencing mechanism and the variability of the factors that can potentially affect it. One could argue that the vast feature space would have led to some degree of overlap, resulting in a spreading of the intensity of a stronger signal over a range of features. The inclusion of a SWAP step in our Bayesian MCMC algorithm, as well as of features spanning different classes (compositional, motifs, structural, thermodynamic) in our analysis should solve overlap issues though, minimising any masking of significant features by less influential ones.

3.1 Motifs

It is particularly interesting that one of the most important features detected by our algorithm is the 3-mer 5′ −3′ motif, ‘UCU’, which has, in the main, escaped the notice of previous siRNA potency studies. More specifically, Teramoto et al. (Teramoto2005) do not report it at all, whereas Vert et al. (Vert et al., 2007) include it in their table of included features, but do not make any special reference to it in their main text or any other distinction between ‘UCU’ and all other motifs studied by them.

‘UCU’ has a positive correlation coefficient, which means that it increases siRNA potency. Including all datasets, 60% of the siRNAs containing the motif are potent for a product level threshold of 0.3 (cf. Table 4). More specifically, motif ‘UCU’ was found present at least once in 2560 siRNAs, of which 1538 were potent. Exclusion of the SIR dataset, where the product level was stated as an ordinal and not as a continuous value, led to qualitatively similar findings, strengthening the confidence in this finding. A detailed breakdown of the motif's occurrences by position in the siRNA sequence can be found in Supplementary Material.

Table 4.

List of features that were most dominant in the generated models

| Feat. ID | Feat No | Occurrence (%) | Corr. Coeff. | Feature explanation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 11 | 94.84 | 0.1029 | NT10 is ‘A’ (cleavage site) |

| 2 | 140 | 93.24 | 0.1485 | Motif ‘UCU’ is present in siRNA |

| 3 | 20 | 88.84 | −0.1213 | NT19 is ‘A’ |

| 4 | 40 | 84.84 | 0.2176 | NT1 is ‘U’ |

| 5 | 433 | 84.54 | 0.2709 | ΔG in NT1..NT4 (dG1-4) |

| 6 | 210 | 78.65 | −0.0972 | Motif ‘ACGA’ is present in siRNA |

| 7 | 437 | 75.42 | 0.1492 | ΔG in NT5..NT8 (dG5-8) |

| 8 | 38 | 69.76 | −0.0034 | NT18 is ‘G’ |

| 9 | 34 | 67.75 | −0.1045 | NT14 is ‘G’ |

| 10 | 483 | 62.84 | 0.0415 | GC content > 35% |

| 11 | 426 | 61.13 | 0.1286 | ΔG in NT13..NT14 |

| 12 | 431 | 58.50 | −0.1495 | ΔG in NT18..NT19 (dG18-19) |

| 13 | 2 | 58.13 | 0.0884 | NT1 is ‘A’ |

| 14 | 491 | 42.33 | 0.2009 | GC content < 70% |

| 15 | 125 | 39.40 | −0.1323 | Motif ‘GCC’ is present in siRNA |

| 16 | 450 | 37.30 | −0.1957 | Folding is present in siRNA (binary value) |

| 17 | 492 | 35.80 | 0.2280 | GC content < 75% |

| 18 | 259 | 33.49 | −0.0911 | Motif ‘GUGG’ is present in siRNA |

| 19 | 347 | 32.84 | 0.0217 | Motif ‘UCCG’ is present in siRNA |

List of features that were most dominant in the models generated by our Bayesian Markov chain Monte Carlo algorithm. The columns depict the overall percentile appearance of each feature (100% representing an appearance of 25 000 000 times in the models generated by our algorithm), the correlation between the feature and the product level variable (positive correlation coefficient indicates an increasing of siRNA potency), as well as its biological meaning. The first thirteen features appear in more than 50% of the runs.

It is important to highlight that the positive correlation found between ‘UCU’ and silencing efficacy is unlikely to reflect a structural or compositional characteristic of the sequences containing the specific motif, as such features were checked for correlation by our Bayesian MCMC algorithm, but were not selected as significant. Other reasons, such as a possible codon-specific bias, can also be excluded (cf. Table 4). Hence, this motif appears to complement the thermodynamic and compositional characteristics that have been previously found to affect siRNA potency, seemingly having a role of its own in the silencing process.

Having established a correlation between the ‘UCU’ motif and siRNA potency, we looked for position-specific effects (cf. Supplementary Material). This revealed increased siRNA potency for samples containing the ‘UCU’ motif at either end of the anti-sense sequence, with a marked drop for samples with the motif at positions NT10-12 and NT11-13. The fact that the drop is observed even when ‘UCU’ is at positions NT11-13 suggests that it cannot be explained on the basis that potent siRNAs prefer an Adenine at NT10, the cleavage site. This is also supported by the fact that the preference for Adenine at NT10 has also been selected as a significant feature by our algorithm.

A second 5′ −3′ motif which seems to affect siRNA potency is the tetranucleotide ‘ACGA’. This is a previously unreported motif which, in contrast to ‘UCU’, appears to negatively affect siRNA potency. Of 219 siRNAs that contain this motif, only 80 appear to be potent. In this case, a position-specific analysis cannot be applied with confidence, given the small number of samples containing that motif (see Supplementary Material for a breakdown of the motif's occurrence by siRNA sequence position). However, it is worth noting that, when ‘ACGA’ appears in positions NT1-4, NT8-11 or, mainly, NT4-7 of the siRNA anti-sense strand, it leads to increased siRNAs potency, whereas in all other positions, and in particular after NT10, it leads to reduced siRNAs potency (cf. Supplementary Material).

Other features which have been selected less often by our algorithm, such as motifs ‘GUGG’, ‘GCC’ and ‘UCCG’, might also be found to be of more importance when larger datasets become available for study in the near future.

Motif ‘UGGC’, which has been previously reported to induce sequence-dependent cell toxicity (Fedorov et al., 2006), was not selected by our MCMC algorithm, although it is well represented in the sample (present in 4.5% of the samples). Moreover, the feature was not found to be significantly correlated with siRNA efficiency, when we performed a single linear regression test.

3.2 Thermodynamic features

Four of the features present in more than 50% of the Monte-Carlo generated models describe thermodynamic properties of the siRNA. It has already been reported that potent siRNA sequences tend to have a less stable 5′ -end (Matveeva et al., 2007; Peek, 2007; Reynolds et al., 2004; Shabalina et al., 2006). Our results confirm this finding, but suggest that the thermodynamic stability of the first tetranucleotide, dG1−4, is a more decisive factor for siRNA potency than that of the first dinucleotide dG1−2, contrary to what has been reported recently (Lu and Mathews, 2008). Similarly, our results suggest feature dG5−8 as preferentially selected over the previously reported dG7−8 (Matveeva et al., 2007), confirming that the thermodynamic stability of the first 7 nt of the siRNA is important for its silencing efficiency. The stability of the 3′ -end of the siRNA seems negatively correlated with siRNA potency, also in line with previous findings (Holen, 2006; Jagla et al., 2005).

A free energy difference between the 5′ and 3′ -ends of the antisense strand, which was previously pointed out as important (Lu and Mathews, 2008; Matveeva et al., 2007), was not selected explicitly by our algorithm—neither in the form of a dinucleotide free energy difference (dG1−2 - dG18−19), a tetranucleotide free energy difference (d4G1−4 - dG16−19), nor in any combination of dinucleotide/tetranucleotide free energy differences (dG1−2 - dG16−19, dG1−4 - dG18−19). In contrast, the free energies of both the first tetranucleotide (dG1−4) and the last dinucleotide (dG18−19) were selected as separate features, in ∼85% and ∼59% of the models, respectively. One way of explaining this is by speculating that the asymmetry between the two ends, which has been previously indicated as important for choosing which of the strands is incorporated into RISC (Shabalina et al., 2006) is not the sole reason that renders the first tetranucleotide (primarily) and the last dinucleotide as important indicators of siRNA efficiency. It should be noted here that Matveeva et al. (Matveeva et al., 2007) have also included the dinucleotide free energies dG1−2 and dG18−19, instead of the respective dinucleotide free energy difference (dG1−2 - dG18−19), in their models. They, however, do not mention their reasoning behind that decision. In order to confirm our speculation, our MCMC algorithm was rerun, leaving the dinucleotide and tetranucleotide free energies of the ends of the antisense strand out, while keeping all other features, including the differences in free energy between the two ends, in. For this reduced feature set, our algorithm did pick up dG1−4 - dG18−19, indicating that it does explain some variation of siRNA potency, but less than that explained when features dG1−4 and dG18−19 are selected together. It should be noted that if dG1−4 - dG18−19 had the same explanatory power as the features dG1−4 and dG18−19, it would have shown up in the initial set-up instead, as the penalized likelihood scheme employed favours models with smaller number of features.

3.3 GC content

A connection between GC content and siRNA potency was previously reported by a variety of studies (Gong et al., 2006; Holen et al., 2002; Matveeva et al., 2007; Pei and Tuschl, 2006; Reynolds et al., 2004). Our MCMC algorithm revealed three GC thresholds as significant for predicting siRNA potency: GC content >35%, GC content <70% and GC content <75%. As the two upper limits for GC content show both a similar correlation and are occurring equally often, we assume the true value to be around 73%. Our algorithm therefore shows that siRNA candidate sequences with GC content in the range of 35–73% have an increased potency. This differs for the GC content windows that were previously proposed (Matveeva et al., 2007; Shao et al., 2006), and it could be considered more reliable, given that it is based on a larger and more diverse dataset.

3.4 Secondary structure

The folding energy of the siRNA sequence, calculated as in (Peek, 2007), is another factor which seems to affect siRNA potency. Given that position-specific bond-formation features are absent from the majority of models returned by our algorithm, the effect of siRNA secondary structure formation on the resulting siRNA potency appears to be adequately captured by the folding energy of the siRNA sequence.

The remaining features selected by our MC algorithm have been previously reported in literature. These include compositional features such as nucleotide U1 (U at NT1), A1 and A10 positively correlated with siRNA potency, and G14, G18 and A19, found to be negatively correlated. The correlation for thermodynamic stabilities dG13−14 and dG18−19 are in line with previous findings (Matveeva et al., 2007) as well.

4 DISCUSSION

The present study had the incentive to explore the feature space more thoroughly than other studies so far, whilst employing the largest meta-dataset reported in literature. We did this in the hope that novel features would be discovered, enabling improved siRNA potency predictions and aiding in a better understanding of the silencing process. It was shown that a Bayesian Markov chain Monte Carlo variable selection method can be successfully employed as a method to quantify the evidence in sets of features and marginally for individual features. This is especially useful when the feature space is too big to be explored deterministically. Moreover, the method can be used to obtain a list of potentially potent siRNAs, which can be further enhanced once additional information, such as transcript details and 3′ overhang data, become available for all entries. Note, however, that our method in its current implementation does not account for siRNA target specificity and structure.

While our algorithm compares well with recently developed siRNA potency predictors (see Supplementary Material for comparative results), the most important part of this study lies in the identification of novel features as significant predictors. Motifs ‘UCU’ and ‘ACGA’ in particular were consistently selected by our MCMC algorithm. To the best of the authors' knowledge, neither of these has been previously reported in the literature as being important for siRNA silencing efficiency. Moreover, the fact that these motifs were selected from a feature set spanning different classes of features and not just motifs reduces the chance of them capturing other, non-specific effects.

The finding that the tetranucleotide thermodynamic stability at the 5′ -end of the siRNA sequence, dG1−4, is more decisive for siRNA potency than the dinucleotide stability, dG1−2, is also very interesting in terms of understanding the mechanism of siRNA incorporation into the RISC complex. It is also worth noting that thermodynamic features dG1−4 and dG5−8 appear to be more important for efficient RNA interference than all compositional ones, apart from the presence of Adenine at NT10, the cleavage site.

It seems clear that future research on siRNA design should attempt to include all possible feature classes in the selection process. We believe we have demonstrated that this can lead to satisfying results. As the amount of available data increases, inferences should be easier to make, and weaker correlations could be captured.

One can only speculate whether the general level of predictive accuracy for siRNA potency is low because of the innate diversity of the siRNA silencing approach, or because some of the important explanatory features are still to be discovered. A crucial step towards answering this question is the availability of the right data, in the right format. So far, there is no consensus on how biological data is extracted or results are reported. This makes comparison of different datasets a challenging and time consuming process. A unified framework would greatly facilitate the replication of reported results and data sharing between different groups. MIARE (Minimum Information About an RNAi Experiment, www.miare.org), a set of guidelines on the information that should be reported for every RNAi experiment, is a significant step towards this direction.

Through the identification of the actual features that influence siRNA-mediated RNA interference, a better understanding of the underlying biological processes could be achieved.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank three anonymous referees for their constructive comments.

Funding: Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council (EPSRC). J.W.K. and L.M. are funded by the EPSRC through the Life Sciences Interface Doctoral Training Centre at Oxford University.

Conflict of interest: none declared.

REFERENCES

- Aza-Blanc P, et al. Identification of modulators of TRAIL-induced apoptosis via RNAi-based phenotypic screening. Mol. Cell. 2003;12:627–637. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00348-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexandrescu A. Modern C++Design: Generic Programming and Design Patterens Applied. Boston: Addision Wesley Professional; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Bernardo JM, Smith AFM. Bayesian Theory (Wiley Series in Probability and Statistics). Wiley; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Ding Y, et al. Sfold web server for statistical folding and rational design of nucleic acids. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:W135–W141. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elbashir SM, et al. Duplexes of 21-nucleotide RNAs mediate RNA interference in cultured mammalian cells. Nature. 2001;411:494–498. doi: 10.1038/35078107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fedorov Y, et al. Off-target effects by siRNA can induce toxic phenotype. RNA. 2006;12:1188–1196. doi: 10.1261/rna.28106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelman A, et al. Bayesian Data Analysis. 2. (Texts in Statistical Science), Chapman & Hall/CRC; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Giddings MC, et al. ODNBase—a web database for antisense oligonucleotide effectiveness studies. Bioinformatics. 2000;16:843–844. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/16.9.843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong W, et al. Integrated siRNA design based on surveying of features associated with high RNAi effectiveness. BMC Bioinformatics. 2006;7:516. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-7-516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong W, et al. siDRM: an effective and generally applicable online siRNA design tool. Bioinformatics. 2008;24:2405–2406. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btn442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harboth J, et al. Sequence, chemical and structural variation of small interfering RNA sans short hairpin RNAs and the effect on mammalian gene silencing. Antisense Nucleic Acid Drug Dev. 2003;13:83–105. doi: 10.1089/108729003321629638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holen T, et al. Positional effects of short interfering RNAs targeting the human coagulation trigger Tissue Factor. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:1757–1766. doi: 10.1093/nar/30.8.1757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holen T. Efficient prediction of siRNAs with siRNArules 1.0: an open-source, JAVA approach to siRNA algorithms. RNA. 2006;12:1620–1625. doi: 10.1261/rna.81006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh AC, et al. A library of siRNA duplexes targeting the phosphoinositide 3-kinase pathway: determinants of gene silencing for use in cell-based screens. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:893–901. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu X, et al. Relative gene-silencing efficacies of small interefering RNAs targeting sense and antisense transcripts from the same genetic locus. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:4609–4617. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huesken D, et al. Design of a genome-wide siRNA library using an artificial neural network. Nat. Biotech. 2005;23:995–1001. doi: 10.1038/nbt1118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson AL, et al. Expression profiling reveals off-target gene regulation by RNAi. Nat. Biotech. 2003;21:635–637. doi: 10.1038/nbt831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson AL, Linsey PS. Noise amidst the silence: off-target effects of siRNAs? Trends Genet. 2004;20:521–524. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2004.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jagla B, et al. Sequence characteristics of functional siRNAs. RNA. 2005;6:864–72. doi: 10.1261/rna.7275905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kass RE, Wasserman L. A reference Bayesian test for nested hypotheses and its relationship to the Schwarz criterion. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1995;90:928–934. [Google Scholar]

- Kass RE, Raftery AE. Bayes factors. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1995;90:773–795. [Google Scholar]

- Katoh T, Suzuki T. Specific residues at every third position of siRNA shape its efficient RNAi activity. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:e27. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl1120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawasaki H, et al. siRNAs generated by recombinant human dicer induce specific and significant but target site-independent gene silencing in human cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:981–987. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Khvorova A, et al. Functional siRNAs and miRNAs exhibit strand bias. Cell. 2003;115:209–216. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00801-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar R, et al. High-throughput selection of effective RNAi probes for gene silencing. Genome Res. 2003;13:2333–2340. doi: 10.1101/gr.1575003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ladunga I. More complete gene silencing by fewer siRNAs: transparent optimized design and biophysical signature. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:433–440. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl1065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leuschner PJF, et al. Cleavage of the siRNA passenger strand during RISC assembly in human cells. EMBO Rep. 2006;7:314–320. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lodish H, et al. Molecular Cell Biology. 5th. New York: WH Freeman; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Lu ZJ, Mathews DH. Efficient siRNA selection using hybridization thermodynamics. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:640–647. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matveeva O, et al. Comparison of approaches for rational siRNA design leading to a new efficient and transparent method. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:e63. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyagishi M, Taira K. siRNA becomes smart and intelligent. Nature Biotech. 2005;23:946–947. doi: 10.1038/nbt0805-946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pancoska P, et al. Efficient RNA interference depends on global context of the target sequence: quantitative analysis of silencing efficiency using Eulerian graph representation of siRNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:1469–1479. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patzel V, et al. Design of siRNAs producing unstructured guide-RNAs results in improved RNA interference efficiency. Nature Biotech. 2005;23:1440–1444. doi: 10.1038/nbt1151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peek AS. Improving model predictions for RNA interference activities that use support vector machine regression by combining and filtering features. BMC Bioinformatics. 2007;8:182–201. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-8-182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pei Y, Tuschl T. On the art of identifying effective and specific siRNAs. Nature Meth. 2006;3:670–676. doi: 10.1038/nmeth911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Persengiev S, et al. Nonspecific, concentration-dependent stimulation and repression of mammalian gene expression by small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) RNA. 2004;10:12–18. doi: 10.1261/rna5160904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phipps KA, et al. Small interfering RNA molecules as potential anti-human rhinovirus agents: in vitro potency, specificity, and mechanism. Antiviral Res. 2004;61:49–55. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2003.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pruit KD, et al. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35(Database Issue):D61–D65. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raftery AE. Bayesian model selection in social research. Sociological Meth. 1995;25:111–163. [Google Scholar]

- Ren Y, et al. siRecords: a database of mammalian RNAi experiments and efficacies. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:D146–D149. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds A, et al. Rational siRNA design for RNA interference. Nat. Biotech. 2004;22:326–330. doi: 10.1038/nbt936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saetrom P. Predicting the efficacy of short oligonucleotides in antisense and RNAi experiments with boosted genetic programming. Bioinformatics. 2004;20:3055–3063. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Semizarov D, et al. Specificity of short interfering RNA determined through gene expression signatures. PNAS. 2003;100:6347–6352. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1131959100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shabalina SA, et al. Computational models with thermodynamic and composition features improve siRNA design. BMC Bioinformatics. 2006;7:65. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-7-65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shao Y, et al. Rational design and rapid screening of antisense oligonucleotides for prokaryotic gene modulation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:5660–5669. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shao Y, et al. Effect of target secondary structure on RNAi efficiency. RNA. 2007;13:1631–1640. doi: 10.1261/rna.546207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teramoto R, et al. Prediction of siRNA functionality using generalized string kernel and support vector machine. FEBS Lett. 2005;579:2878–2882. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2005.04.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ui-Tei K, et al. Guidelines for the selection of highly effective siRNA sequences for mammalian and chick RNA intereference. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:936–948. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vert JP, et al. An accurate and interpretable model for siRNA efficacy prediction. BMC Bioinformatics. 2007;7:520. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-7-520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vickers TA, et al. Efficient reduction of target RNAs by small interfering RNA and RNase H-dependent antisense agents. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:7108–7118. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M210326200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, et al. Structure of an argonaute silencing complex with a seed-containing guide DNA and target RNA duplex. Nature. 2008;456:921–926. doi: 10.1038/nature07666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.