Abstract

Motivation: Throughout evolution, homologous proteins have common regions that stay semi-rigid relative to each other and other parts that vary in a more noticeable way. In order to compare the increasing number of structures in the PDB, flexible geometrical alignments are needed, that are reliable and easy to use.

Results: We present a protein structure alignment method whose main feature is the ability to consider different rigid transformations at different sites, allowing for deformations beyond a global rigid transformation. The performance of the method is comparable with that of the best ones from 10 aligners tested, regarding both the quality of the alignments with respect to hand curated ones, and the classification ability. An analysis of some structure pairs from the literature that need to be matched in a flexible fashion are shown. The use of a series of local transformations can be exported to other classifiers, and a future golden protein similarity measure could benefit from it.

Availability: A public server for the program is available at http://dmi.uib.es/ProtDeform/.

Contact: jairo@uib.es

Supplementary information: All data used, results and examples are available at http://dmi.uib.es/people/jairo/bio/ProtDeform.Supplementary data are available at Bioinformatics online.

1 INTRODUCTION

Each time a 3D structure of a protein is determined, it is necessary to know of other proteins that have similar structures so that the function of the new protein, if unknown, may be inferred. The PDB (Kouranov et al., 2006) is growing fast, with rapid development expected in the next decade as a result of (or as an input to) proteomics. The need to compare protein structures is therefore evident. There are already good protein aligners available to researchers but there is absolutely no consensus on the best one. Thus, the knowledge of an objective way of comparing protein structures is lacking.

Several protein structure comparison methods rely on a single rigid transformation to measure the quality of the superposition of two structures, for example, Rash (and also Gash) (Standley et al., 2007), TM-align (Zhang and Skolnick, 2005) and Structal (Levitt and Gerstein, 1998). Others, i.e. Dali (Holm and Sander, 2000) and Matras (Kawabata and Nishikawa, 2000), whose results are among the ones in the highest agreement with the standard protein databases, allow distance distortions not controlled by a single transformation although the score for a single alignment pair depends on all others pairs. Some others consider proteins as flexible objects, i.e. they are designed to allow local changes during structural comparison; Matt (Menke et al., 2008) and PPM (Csaba et al., 2008) are the main representatives of this new generation of comparison methods that started with SAP (Taylor, 1999) and FlexProt (Shatsky et al., 2002). Usually, some domain parts are rigid or semi-rigid like α-helices and β-strands, and other parts act as articulation points, i.e. turns. The ProtDeform algorithm that we describe here also considers proteins as flexible objects and thus belongs to this last generation of algorithms. We find that our algorithm performs better or similar to the ones mentioned above.

We review the core of each of these systems, specifically their scoring functions, in order to highlight the main differences between the existing algorithms and the one we propose. The similarity scores used by Dali and Matras are alike. Given a pair of sites that are matched to a corresponding pair in another protein, if d is the distance difference between the two pairs, Dali's individual score is  , where

, where  is the average distance, and a and b are defined constant values; and the total score is the sum (a double sum, in fact) over all possible pairs. Similarly, Matras sums the likelihood of matching with a difference d (same value considered by Dali) taking into account the site distances over the chains considering all site pairs of a protein. A close look over the likelihood values shows that for large values for d, the values are low, as in Dali, but in this case the values come from evidence of occurrence gathered during training. It is clear that there is no global transformation in any of these two systems but any assigned site influences the score of the others. Dali's algorithm is complex but it is the best among several benchmarks, and new versions have been made public each year for the past decade. Our aim is to get a better and simpler algorithm that would be comparable with the best ones available.

is the average distance, and a and b are defined constant values; and the total score is the sum (a double sum, in fact) over all possible pairs. Similarly, Matras sums the likelihood of matching with a difference d (same value considered by Dali) taking into account the site distances over the chains considering all site pairs of a protein. A close look over the likelihood values shows that for large values for d, the values are low, as in Dali, but in this case the values come from evidence of occurrence gathered during training. It is clear that there is no global transformation in any of these two systems but any assigned site influences the score of the others. Dali's algorithm is complex but it is the best among several benchmarks, and new versions have been made public each year for the past decade. Our aim is to get a better and simpler algorithm that would be comparable with the best ones available.

Structal relies on a single rigid transformation that minimizes RMSD. Gash and TM-align also rely on a single rigid transformation, but not on the one that minimizes RMSD: their transformations maximize the sum of individual scores that gives less importance to outliers. If d is the distance between superposed sites, Gash's individual score has the form exp(−d2/a), where a is a defined constant. On the other hand, TM-align's individual score has the form 1/(1+d2/a), where a is a constant for all sites but depends on the query domain length.

Matt is a protein alignment method which allows flexible deformations of the protein backbone. Bending and rotations of the backbone are considered when locating an alignment between two proteins. This allows Matt to accommodate structural distortion where the protein shapes become increasingly divergent along the backbone. Matt uses an initial rigid alignment of multiple fragments from the proteins. These fragments are then merged, allowing rotations and bending in the combination. The best alignment pair of merged fragments are kept. Iterative application of this process results in a final single merged and aligned structure.

PPM also allows flexible superpositions, and starts with a rigid alignment of backbone fragments, too. The best fragment pairs under a certain measure are the nodes of a graph, and the cost among these nodes measures how well the two pairs of fragments can be aligned. Using the A* algorithm, a search tree is constructed that increases the number of compatible pairs on partial pair lists until an optimal pair list is reached under certain criteria for the allowed bending. The method outperforms TM-align and Vorolign (Birzele et al., 2006), this latter one, a method from the same research group.

In general, the use of a single rigid transformation for protein comparison has gained much popularity among researchers in the field. There is now some evidence that the gold standards for classification, e.g. CATH (Orengo et al., 1997) and SCOP (Murzin et al., 1997), should not be hierarchical, as they do not reflect the continuum of protein shape. The scores proposed as new gold standards depend again on a single rigid transformation (Kolodny et al., 2005; Zhang and Skolnick, 2004). For instance, in the latter paper cited, the value RMSD/Nassign, where Nassign is the number of aligned pairs is proposed as a geometric measure of an alignment.

In this article, we present a method for protein structure alignment which is, as far as we know, one of the best methods with respect to CATH and Sisyphus. In other words, when applied on a big population of protein pairs it is one of the best on the average. The key difference of our method with respect to most of the above methods is that it considers a sequence of local rigid transformations as opposed to a single transformation or to a global influence of each single assignment. A single transformation helps to measure how good a site alignment is with respect to all others. However, since the dynamics of the molecule prevents the consideration of a single transformation, we opted for considering a transformation for each site. Thus, each so called local transformation covers a site neighbourhood, small enough so that it can be different from others at far away protein places, but big enough so that adjacent transformations are similar and no large distortions are allowed without penalty.

The method iterates alternatively between finding a match and a score matrix that stores the quality of matching of each site in one protein to each site of the other protein. The process is similar to the other algorithms, e.g. TM-align and Structal, but the heart of the scoring mechanism is locally based.

2 METHODS

All formulae and parameters found appropriate for a training set of 939 pairs, the same pair set used by Holm and Sander (2000), have been used throughout the testing experiments. On this set, several combinations of parameters or formulae were tried, and the combination we found the most suited was fixed for the testing sets and the server's parameters. We did not use an exhaustive procedure to get the parameters, so these ones are not optimized in any way. Usually, we searched for values similar to those that other researchers reported as useful or near certain values we have some intuitive reason to believe were worth trying.

To measure the performance of the system, there are three testing sets, one of 106 difficult pairs from the hand curated Sisyphus database, one of more than 230 000 pairs of CATH proteins, and one of more than 12 000 domain pairs from SCOP, as we shall explain later.

In order to describe the algorithm, we present some basic definitions.

2.1 Notation and basic definitions

We denote complete protein structures by uppercase letters A, B. Each protein structure is given with its complete set of x, y, z coordinates for all its atoms. We reduce this representation to the α-carbon backbone atoms A={ai}i=1n={(axi, ayi, azi)}, where n is the number of amino acids. They are ordered following their own order in the protein chain, and each of them is called a protein site.

Let A={ai}i=1n and B={bi}i=1m be two proteins. A score matrix for A and B is a n × m-matrix M =(mi,j), i=1,…, n, j=1,…, m. Intuitively, mi,j measures a likelihood of matching site ai in A to site bj in B. A matching or alignment is a partial one-to one order preserving function f : A → B. We denote by Dom(f) the domain of a matching f, and Nassign, the number of pairs in f.

Given a site ai in A, we define the neighbourhood VAi ⊆A as the set of the Nv nearest sites in A to site ai. We use Nv = 38. As mentioned earlier, we tried several values for this constant starting with a much lower value on the training set. However, the computational experiments convinced us that the neighbourhoods should share a large number of sites.

Given a site ai in A, a site bj in B and a matching f : A → B, we define Xijf as the set of sites in A such that the site and its image are in the neighbourhood of ai and bj, respectively. More formally, ak ∈ Xijf when ak ∈ VAi ∩ Dom(f) and f(ak) ∈ VBj. The local transformation Tijf is the best rotation and translation from the B coordinate system to the A coordinate system that minimizes the following expression

When Xijf has less than three elements, we say that the transformation is not defined. In words, the transformation Tijf is the best one for the alignment f restricted to neighbours of the site ai and bj.

2.2 Goals

Ideally, given two proteins, we would like to find a matching f that maximizes the expression

for d0 a fixed constant (we shall discuss details about this constant later). Intuitively, the formula prefers alignments with a large domain provided that outlier alignments do not deviate the local transformations. The matching of a site should also be in a locally rigid agreement with the matching of its neighbours under a sigmoid function that penalizes distances far from d0 Å. The gap values are calculated in such a manner so as to prefer gaps instead of poor alignments. We also would like to avoid isolated site alignments.

The optimization problem defined above is very tough and we ignore how to find a solution for it. In the algorithm we describe next, we try to approximate the optimal solution of the expression above by an iterative procedure. Starting with an initial distance among protein sites obtained from a secondary structure matching, we calculate the optimal alignment for that distance matrix, and then calculate a new distance matrix from the alignment and then repeat the procedure for a small number of iterations.

3 ALGORITHM

The algorithm consists of three main steps. First, we initialize a score matrix based on the first classifier in Matras (Kawabata and Nishikawa, 2000). Second, this score matrix is used to determine a matching between sites by using a dynamic programming approach. And third, this matching is used to compute a set of local transformations. Each transformation maps the local structure of one protein onto the other. Armed with these transformations, we then compute a new score matrix which is based on the distance between the transformed sites. These last two steps are iterated until convergence or a maximum number of steps is reached. Convergence is reached when the matching does not change between successive steps. At the end, we compute a final score for the similarity. These steps are described below.

3.1 Initialization step

We obtain an initial secondary structure matching between two given proteins using only the first classifier of Matras (Kawabata and Nishikawa, 2000). This protein matching system uses three classifiers sequentially to get a final matching, all three relying on likelihood information obtained during training.

For completeness, let us summarize the function of each classifier of Matras. The first classifier assigns secondary structure elements (SSEs) (α-helices and β-strands) using their geometrical features (relative angles and distances). The second one uses environmental features such as water exposure and SSE type to improve the SSE-matching. The final classifier uses only distance information between amino acid pairs to get the final matching starting from the output of the previous classifier.

We choose Matras' first classifier because it uses a branch and bound search under several geometric constraints that we found robust. However, our system can read SSE matchings from any other source.

As mentioned, the entry mi,j of the score matrix represents the likelihood that the site ai is matched to the site bj. Thus, if the SSE Ar is matched to the SSE Bs by Matras, and ai is in Ar and bj is in Bs, then mi,j should have a high value. We initialize a score matrix as follows. Assume that a SSE Ar is matched to a SSE Bs. If they have equal length, we assign a score of 1 for matching the first site of Ar to the first site of Bs, and so on until the entry for the last sites is also set to 1. In other words, we consider the square formed by the sites with the first coordinate in one structure and the second coordinate in the other structure in the score matrix M, and the square diagonal is set to 1. Similarly, if the SSE matched pair is not made of SSEs of the same length, we consider its corresponding rectangle, and set to 1 all its sub-diagonals at 45° as is exemplified in Figure 1. All the other entries of the matrix are set to 1.1 of the gap value. In this way, the algorithm in the next step prefers to match pairs on the sub-diagonals, followed by pairs outside the sub-diagonals, and then, if the previous ones are not possible, it introduces gaps. The value of a gap is fixed below.

Fig. 1.

In this score matrix, the thick lines represent SSE. If the first SSE on the first domain is matched to the first one on the second domain, and the same for the second SSEs, then the entries on diagonal segments shown have a higher likelihood than the other entries.

3.2 Matching update

The algorithm finds the matching f that maximizes the value

| (1) |

In other words, we find an alignment of the two chains that respects the order of the chains and maximizes the likelihood values in the score matrix.

We use dynamic programming with a gap value of exp(−(9/d0)2) times the number of sites not matched; several values were tried for this value during training; d0 is defined below. Intuitively, the gap value makes that two sites that are superposed with a distance among them >9 Å be a poorly aligned pair. We forbid the alignments of site segments of length below 6, e.g. any matched site has at least four other consecutive sites also matched.

3.3 Matrix update

Given a matching f, we calculate Tijf, the local transformation at sites i and j, and

In this way, we capture the distance from ai to the image of bj after it is locally transformed. Then, we use the term:

When the transformation Tijf is not defined we set mi,j =0. The value of d02 is 11.5 Å2 and defines the range of distance deviations that contribute more positively to the score. This parameter, or another one with a similar purpose, appears in the scoring functions of several systems. Rash recommends a larger value, rcut =4 Å, probably because for using a global transformation for the whole protein a wider range of values should be allowed. Dali uses a much larger one, b = 20 Å, but there it is used more to define the neighbourhood of influence of a site. Our value does not depend on the protein length as in the TM-score (Zhang and Skolnick, 2004) because the transformations do not have to cover the whole protein.

3.4 Final step

When f is left unchanged or a maximum number of steps Imax is reached, the process halts. In our test, Imax = 5. As with other constants, several tries where performed during training and it was found that although the value Imax is primarily responsible for slowing the system, it gives it a certain robustness.

We found that considering several initial SSE alignments, the system works better during training: we modified Matras so that the output contains up to four best SSE alignments and the entire procedure described above is repeated for each one. Then, the best under the score (1) is considered.

The system is invariant to the order in which the two proteins are written because our definitions are symmetric.

We now define a score that allows the method to sort the most similar structures in a database to a query structure. The score is the ratio between the optimal path value on the score matrix [i.e. the raw score (1)] and its length (i.e. the sum of protein lengths minus the alignment length). Since the path length grows as the number of non-matched sites increases, the higher the raw score and the shorter the length, the better. Intuitively, this ratio measures the average quality of the alignment over aligned and non-aligned sites. We found that the score worked well during training when comparing matching quality across different proteins against the same query:

| (2) |

where Nassign is the number of matched sites, and m is the query protein length and n is the target protein length.

The output of the algorithm includes the list of aligned pairs (i,f(i))i∈Dom(f) and, for display purposes, the list of aligned intervals with their associated transformation ([ik, ik′], [f(ik), f(ik′)], Tk)k; in this one, all the amino acids in the first interval [ik, ik′] are aligned to their respective amino acids in the second interval [f(ik), f(ik′)] under the same transformation Tk in homogeneous representation (a 4×4 matrix, in which the top left 3×3 matrix is the rotation matrix and the fourth column is the translation vector with a 1 in the fourth position).

4 IMPLEMENTATION AND TESTING

The implementation was written in C++, with scripts in Perl to call the Matras program and all the needed format translations between them so that it is naturally slower than other methods that use only one global transformation. However, this prototype program is not yet optimized for speed: when all the programs be integrated in one binary, the program could be faster.

For testing, we use three benchmarks, the difficult hand curated alignments by Mayr et al. (2007), the classification benchmark by Sierk and Pearson (2004) and the benchmark at the Fatcat server. In this way, we measure and compare the quality of the alignments themselves and the system ability for classification. We also show some of the now standard alignments that need flexibility, as discussed by Yuzhen and Godzik (2003).

We tested 10 methods including ours: ProtDeform, SSAP (Taylor and Orengo, 1989), Dali, FlexProt, Matras, TMalign, Rash, Vorolign (Birzele et al., 2006), PPM and Matt. The results for FlexProt were poor and were eliminated from the figures because they may be caused by simple problems reading the PDB numberings, and also it does not provide an alignment score. We tried to fix those problems but finally we do not consider doing it fair with the other methods.

4.1 The Sisyphus benchmark

The Sisyphus database contains manually curated multiple structure alignments (Andreeva et al., 2007). Mayr et al. (2007) gave some difficult protein pairs and applied six comparison programs to them. Alignments were calculated by CE, Dali, Fatcat, Matras, Cα-match and Sheba for each pair in the set. Then, they evaluated the comparison methods according to the reference alignments. From the 125 pairs (available at http://biwww.che.sbg.ac.at/RSA/), we eliminated the ones with more than one chain, and got a set of 106 pairs.

The agreement to a reference alignment was computed as the percentage of residues aligned, with a tolerance shift of s positions, to the reference alignment (Is) relative to the length of the reference alignment (Lref): Is/Lref. I0 is the number of identically aligned residues in the reference and the method alignments; I1 is I0 plus the number of aligned residues that are shifted by one position, and so on.

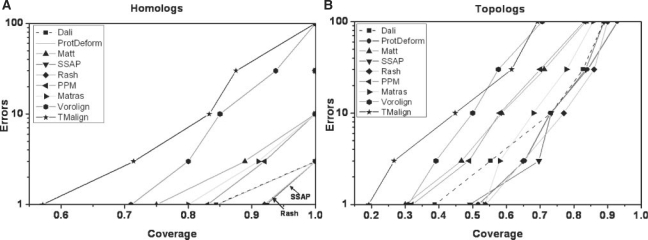

Among the 10, the best method is Matt with an average exact agreement among the 106 pairs of 82%, distinctly higher than the others, as seen in Figure 2. If the tolerance shift is increased, it gets above 90%. The second best is ProtDeform, except for exact alignments, case in which the best one is Dali with 80%. The third is Dali, and then all the others come close to each other. Rash has a poor performance on exact alignments, then it recovers quickly, which means that its alignments are not far from the truth.

Fig. 2.

Average percentage of agreement to reference alignments for each tolerance shift allowed.

The average speed of the algorithms on an Intel Centrino Duo at 1.66 GHz running Linux is summarized in first row of Table 1. Matras has the best quality to speed ratio in this test.

Table 1.

The first row shows the speed of the programs in average number of seconds per pair; the other rows show the percentage of queries that get as the best score a domain of the correct type; second and third rows, in the benchmark based on CATH; forth and fifth, based on SCOP.

| SSAP | Dali | Matt | Rash | ProtDefrom | PPM | Matras | TMalign | Vorolign | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time (s/pair) | 23.9 | 21.9 | 12.4 | 10.4 | 8.5 | 3.6 | 1.1 | 0.9 | 0.6 |

| Homology CATH | 96.5 | 91.9 | 88.4 | 97.7 | 96.5 | 93.0 | 94.2 | 84.7 | 90.6 |

| Topology CATH | 100 | 94.2 | 90.6 | 98.8 | 96.5 | 95.3 | 97.7 | 86.0 | 94.2 |

| Family SCOP | 80.9 | 83.7 | 81.1 | 82.1 | 81.8 | 83.7 | 82.6 | 77.7 | 83.9 |

| Fold SCOP | 95.3 | 96.1 | 91.1 | 94.1 | 94.1 | 94.3 | 95.3 | 89.3 | 93.8 |

4.2 The CATH benchmark

The second benchmark is a subset of CATH 2.3 database [which stands for Class, Architecture, Topology and Homology (Orengo et al., 1997)], selected by Sierk and Pearson (2004) to obtain a non-redundant sample of the entire database. A 2771 subset of CATH domains and 86 prototype domains (available at the FASTA repository ftp.virginia.edu:/pub/fasta /prot_sci_04) were selected to test the following algorithms: Dali, Structal, CE, VAST, Matras, SGM, PRIDE, SSEARCH and PS-Blast. This domain set was carefully screened in order to be considered as a valid benchmark for testing protein comparison algorithms. Of the 2771 domains, 1120 belong to the 86 families of the 86 prototypes. Therefore, when comparing each of the 2771 domains against each of the 86 prototypes, there are a maximum of 1120 correct hits at the Homology level. The prototypes are part of these 1120 domains. Also, there is a maximum of 7048 hits at the Topology level, e.g. 7048 pairs that are topologs.

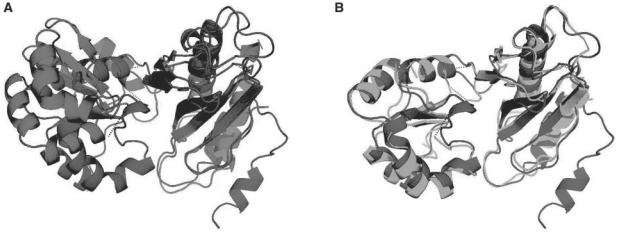

To test a classifier with this benchmark, it is applied carrying out a comparison of each of the 86 prototypes versus the 2771 domains. The values returned are examined from the best score to the worst. For each query, each target considered in this order whose domains belong to the same Homologous family, a Hit (coverage) value is increased. Otherwise, an Error value is increased. Then, the level of coverage by the median query (43 queries performed better, 42 worse) is calculated at the 1st, 3rd, 10th, 30th and 100th error. We also plot the same curves but when hits are topolog pairs (until the Topology classification) and errors are non-topolog pairs. The results are shown in Figure 3 for Homologs and Topologs. This is the method used by Sierk and Pearson (and displayed in their Figure 2A and C) to evaluate the other algorithms with the same database and measure the performance for the individual queries. We keep the same type of figures so our results can be compared directly with the ones obtained by Sierk and Pearson (our results for Matras are better because we use the new version 1.2).

Fig. 3.

(A) Hits (coverage) against errors for the median query, at the homology level (ProtDeform and Dali coincide). (B) Same as above but considering the topology level.

Considering that in many applications it is important to identify the correct family for a domain query with a very high precision, we calculate how often each of the methods tested is able to identify a correct member of the homology/topology level in the first position of the list. The results are in the second and third rows of Table 1.

We can see in Figure 3 and in the second row of Table 1 that the new algorithm is, with SSAP and Rash, among the three best algorithms with respect to CATH at the Homology level. As shown Figure 3(B), and in the third row of the table, ProtDeform is among the best four algorithms with Rash, Matras and SSAP at the Topology level. Rash score has a surprising best agreement with respect to CATH at both Homology and Topology levels: half of the queries obtained 93% of coverage for Homology before generating the first error, and 54% for Topology; it is surprising because Rash was trained only for topology agreement using as independent measures of truth both CATH and SCOP classifications. Meanwhile, SSAP score high agreement maybe due to the use of SSAP for the creation of the CATH hierarchy; anyway, Rash, in fact, outperforms SSAP if we consider both levels together. Therefore, the CATH hierarchy shows certain independence from SSAP since it can be better reproduced by another program trained using both CATH and SCOP topology classification. After them, ProtDeform shows a remarkable coverage of 85% for homology and 52% for topology for half of the queries before the first error is hit. Altogether, there is in fact a group of methods that perform well in this test: Rash, SSAP, ProtDeform, PPM, Dali and Matras.

4.3 The SCOP benchmark

In order to see a different side of the methods being tested for classification, we consider a benchmark from the Fatcat server (http://fatcat.burnham.org). It has 15 000 domain pairs from SCOP. We consider each domain that is paired with at least one domain in the same family and at least one domain not in the same family and got 12 364 pairs with 796 queries. Similarly, at the fold level, we got 9564 pairs with 1583 queries. Then, we found the percentage of queries for which a given method finds a domain of the same family/fold at the top of the list. The results are in rows four and five in Table 1.

The best methods in this test for both fold and family levels are Dali, PPM and Matras. Just after them, we find ProtDeform and Rash. Vorolign, which performs poorly in both the Sisyphus and CATH benchmark has a surprisingly good performance only at the family level. SSAP does poorly at the family level, but it is does very well at the fold level. TMalign is the only one that performs poorly at all tests.

4.4 Some examples

The similarity between two different proteins could need relative motion for some parts beyond what traditional RMSD-based structure alignment tools allow. We show here one example suggested in Yuzhen and Godzik (2003), where these deformations can be spotted easily. Additional examples are shown in the Supplementary Material.

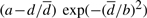

In Figure 4, we can see a good superposition between two proteins spanning their entire structures. The first one is the ribosomal protein L1 mutant S179C from Thermus thermophilus (SCOP code d1ad2a, in black) and the second one, the 50S ribosomal protein L1P from Methanococcus jannaschii (SCOP code d1cjsa, in gray). Both proteins have two domains and for the matching found, it is apparent from the superposed protein chains that the alignment is much better with the deformation being permitted compared with a rigid transformation which can align only one domain satisfactorily. The results are very similar to the one in the above cited paper, where some biological importance is highlighted: researchers have studied the conformational flexibility of ribosomal protein L1 and showed that this protein has a small but significant opening of the cavity between its two domains, which is suspected to be necessary to accommodate the larger conformational change needed for an induced fit mechanism upon binding RNA.

Fig. 4.

Comparisons between the ribosomal protein L1 mutant S179C [SCOP code d1ad2, in blue (black)] and the 50S ribosomal protein L1P from Methanococcus jannaschii [SCOP code d1cjsa, in green and red (gray)]. (A) The superposition of these two proteins according to the best rigid superposition possible for the matching found. It is apparent that only one domain from each protein is superimposed in this manner. Several local transfomations, however, allow a much better superposition (B).

5 DISCUSSION

We have investigated the utility of using the ProtDeform algorithm to automatically find the alignments that expert hands define as most likely, and to recognize domains with the same CATH homology and topology. Our algorithm is as good as Dali and Matras for hand curated alignments, but it is outperformed by Matt; Rash's accuracy is relative low for this test. With respect to CATH, ProtDeform is outperformed by Rash and SSAP; Matt classification ability is rather low. With respect to SCOP, Dali, Matras and PPM are the best. Meanwhile, ProtDeform seems to perform well under all criteria. Overall, we believe that most methods (ProtDeform, Rash, Matt, Dali, Matras, PPM and SSAP) have great performance. Therefore, ProtDeform is among the best classifiers and it is superior to more traditionally single transformation ones like TM-align.

It is clear that our results are valid for the benchmarks used, which have been carefully screened by other researchers. However, an objective measure for protein similarity would be useful also to us, although no one is widely accepted yet. We could propose our score in Formula (2) as possible gold standard, but we still cannot argue why this or other related measures should be the one in spite of the allowed flexibility inherent in them. In fact, we make emphasis that the measure, if it exists, has not to be simple.

Meanwhile, we could regard our results as an update to the comparison over the Sisyphus subsets and in Sierk and Pearson's comparison paper, adding seven classifiers to both studies. We also consider that ProtDeform, Rash, Matt, Dali, Matras, PPM and SSAP are among the best classifiers to date. If Rash could improve the alignment precision, or Matt, its classification score, any of the two could become the most reliable ones on both criteria.

We believe that our sequence of local transformations approach could improve several classifiers. Rash, for instance, could easily be modified to find a sequence of local transformations for an alignment, instead of trying to find a single rigid transformation (although a new training for Rash would be needed). As stated earlier, our system could be seen roughly as changing, in TM-align or Structal, the routine that finds a single rigid transformation for a routine that finds the sequence of local transformations. Our results show that we already have improved them: see the results for Structal in Sierk and Pearson (2004). Since we use Matras' first classifier, we can also argue that we have outperformed its second and third classifiers with respect to Sisyphus and CATH.

ProtDeform alignments deform one of the domains in a way that does not have to resemble a single rigid transformation, so that the two matching examples shown above have been selected as simple although comprehensible from a single shot. It could be that our deformations are too lenient and sometimes cause alignments that experts would never allow. We are convinced that more research is needed based on the local transformation approach that includes the possibility of reducing the number of neighbours as the iterations progress, selecting the neighbours according to more information on secondary structures, sequence proximity, hydrophobicity, etc., and adding knowledge-specific strategies to neighbour selection by analysing the errors with experts.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Takeshi Kawabata made the Matras code available and Daron Standley gave to us ASH and its output on the CATH benchmark. Peter Lackner created the new Sisyphus benchmark. Vladimir Galatenko brought ASH to our attention. Fabian Birzele and Gergely Csaba applied Vorolign and PPM to the benchmarks we used. Antoni Pisà made the PYMOL scripts to get the images. Mercè Llabrés and Francesc Rosselló helped to improve the manuscript. Max Shatsky answered our questions on FlexProt. Alexander Tuzikov helped get and manage the INTAS project. The anonymous referees made this manuscript much more richer. We are grateful to all.

Funding: Spanish Ministery of Science and Technology (MTM 2005Â -8567, MTM 2006-17773); International Association for the promotion of co-operation with scientists from the New Independent States of the former Soviet Union (INTAS 04-77-7178).

Conflict of Interest: none declared.

REFERENCES

- Andreeva A, et al. SISYPHUS: structural alignments for proteins with non-trivial relationships. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:D253–D259. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birzele F, et al. Vorolign: fast structural alignment using Voronoi contacts. Bioinformatics. 2006;23:205–211. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Csaba G, et al. Protein structural alignment considering phenotypical plasticity. Bioinformatics. 2008;24:98–104. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btn271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holm L, Sander C. Protein structure comparison by alignment of distance matrices. J. Mol. Biol. 1993;233:123–138. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1993.1489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawabata T, Nishikawa K. Protein structure comparison using the Markov transition model of evolution. Proteins: Struct. Funct. Genet. 2000;41:108–122. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolodny R, et al. Comprehensive evaluation of protein structure alignment methods: scoring by geometric measures. J. Mol. Biol. 2005;343:1173–1188. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.12.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kouranov A, et al. The RCSB PDB information portal for structural genomics. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34(Database issue):302–305. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkj120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levitt M, Gerstein M. A unified statistical framework for sequence comparison and structure comparison. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1998;95:5913–5920. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.11.5913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayr G, et al. Comparative analysis of protein structure alignments. BMC Struct. Biol. 2007;7:50. doi: 10.1186/1472-6807-7-50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menke M, et al. Matt: local flexibility aids protein multiple structure alignment. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2008;4:88–99. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.0040010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murzin AG, et al. SCOP: a structural classification of proteins database for the investigation of sequences and structures. J. Mol. Biol. 1995;247:536–540. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1995.0159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orengo CA, et al. CATH- a hierarchic classification of protein domain structures. Structure. 1997;5:1093–1108. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(97)00260-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shatsky M, et al. Flexible protein alignment and hinge detection. Proteins Struct. Funct. Genet. 2002;48:242–256. doi: 10.1002/prot.10100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sierk M, Pearson W. Sensitivity and selectivity in protein structure comparison. Protein Sci. 2004;13:773–785. doi: 10.1110/ps.03328504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Standley DM, et al. ASH structure alignment package: sensitivity and selectivity domain classification. BMC Bioinformatics. 2007;8:116. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-8-116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor WR. Protein structure comparison using iterated double dynamic programming. Protein Sci. 1999;8:654–65. doi: 10.1110/ps.8.3.654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor WR, Orengo CA. Protein structure alignment. J. Mol. Biol. 1989;208:1–22. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(89)90084-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuzhen Y, Godzik A. Flexible structure alignment by chaining aligned fragment pairs allowing twists. Bioinformatics. 2003;19:246–255. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg1086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Skolnick J. Scoring function for automated assessment of protein structure template quality. Proteins Struct. Funct. Bioinform. 2004;57:702–710. doi: 10.1002/prot.20264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Skolnick J. TM-align: a protein structure alignment algorithm based on the TM-score. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:2302–2309. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.