Abstract

The Y chromosome, inherited without meiotic recombination from father to son, carries relatively few genes in most species. This is consistent with predictions from evolutionary theory that nonrecombining chromosomes lack variation and degenerate rapidly. However, recent work has suggested a dynamic role for the Y chromosome in gene regulation, a finding with important implications for spermatogenesis and male fitness. We studied Y chromosomes from two populations of Drosophila melanogaster that had previously been shown to have major effects on the thermal tolerance of spermatogenesis. We show that these Y chromosomes differentially modify the expression of hundreds of autosomal and X-linked genes. Genes showing Y-linked regulatory variation (YRV) also show an association with immune response and pheromone detection. Indeed, genes located proximal to the euchromatin–heterochromatin boundary of the X chromosome appear particularly responsive to Y-linked variation, including a substantial number of odorant-binding genes. Furthermore, the data show significant regulatory interactions between the Y chromosome and the genetic background of autosomes and X chromosome. Altogether, our findings support the view that interpopulation, Y-linked regulatory polymorphisms can differentially modulate the expression of many genes important to male fitness, and they also point to complex interactions between the Y chromosome and genetic background affecting global gene expression.

THE Y chromosome is transmitted without sexual recombination from father to son. In the Y chromosome, as in other nonrecombining regions, complete linkage between genes results in the accumulation of deleterious alleles and the loss of genetic diversity due to the evolutionary processes of Muller's ratchet, background selection, and genetic hitchhiking (Bull 1983; Rice 1987; Charlesworth and Charlesworth 2000; Bachtrog et al. 2008). Consistent with theory, the Y chromosome of Drosophila melanogaster carries only 13 known protein-coding genes (Carvalho et al. 2001; Carvalho and Clark 2005; Koerich et al. 2008; Vibranovski et al. 2008; Krsticevic et al. 2010), whereas >5000 genes would be expected from typical gene densities in euchromatic regions.

Six of the 13 genes discovered on the Y chromosome are male fertility factors that either encode structural components of spermatogenesis or regulate spermatogenesis-specific processes such as individualization (Carvalho et al. 2000, 2009). Spermatogenesis in Drosophila males is extremely sensitive to heat, with males becoming sterile anywhere from 23° in heat-sensitive species to 31° in heat-tolerant species (Chakir et al. 2002; David et al. 2005). In D. melanogaster, Rohmer et al. (2004) found that differences between Y chromosome lineages from tropical and temperate regions are responsible for much of the variation in thermal sensitivity of spermatogenesis. Since spermatogenesis is essential for male fitness, we expect a Y chromosome effect on thermal sensitivity to translate into effects on male fitness. However, Y chromosome effects on fitness can occur even at constant temperatures: Chippindale and Rice (2001) showed that polymorphisms in the Y chromosome have a large effect on male fitness, with total genetic variance in fitness comprising a limited contribution of additive genetic variance but a substantial contribution of epistatic genetic variance. Accordingly, the contribution of a Y chromosome to fitness was found to be highly dependent on the genetic background of autosomes and the X chromosome.

While Y-linked protein-coding genes show effectively no nucleotide diversity (average pairwise differences, π) within D. melanogaster (Zurovcova and Eanes 1999) and very low levels of diversity in human populations (Shen et al. 2000; Rozen et al. 2009), Y-linked heterochromatic and rDNA repeats in both flies and humans can differ in repeat number or length (Lyckegaard and Clark 1989, 1991; Karafet et al. 1998; Repping et al. 2003). Moreover, recent studies showed that the Y chromosome has undergone rapid evolution and turnover of protein-coding genes between humans and chimpanzees (Hughes et al. 2010) as well as among species of Drosophila (Koerich et al. 2008).

While no Y-linked transcription factors have been found in Drosophila, the Y chromosome is known to be a pervasive modulator of gene activity elsewhere in the genome. One phenomenon in which the Y chromosome affects expression of genes is position-effect variegation (PEV) (Muller 1930; Gatti and Pimpinelli 1992; Talbert and Henikoff 2006; Schulze and Wallrath 2007). PEV occurs when genes are relocated next to a heterochromatin–euchromatin boundary. While these genes remain unchanged at the DNA level, they are transcriptionally repressed in some cells but not others. A classic example is the repositioning of the w[m4] allele from its normal location in euchromatin near the tip of the X chromosome to a new location close to an AT-rich microsatellite region in the pericentromeric heterochromatin near the base of the X (Muller 1930). The variegated expression of w[m4] results in a mosaic, red–white eye-color phenotype. PEV-associated repression of gene transcription is thought to result from the spread of pericentromeric heterochromatin into neighboring genes with consequent transcriptional silencing of those genes (Schulze and Wallrath 2007). Y-chromosomal heterochromatin is known to suppress PEV in both XY males and XXY females (Dorer and Henikoff 1994), with the level of suppression proportional to the amount of the Y chromosome heterochromatin present (Dimitri and Pisano 1989). One model for these effects is the competitive sequestration of chromatin-associated proteins by Y-linked microsatellite repeats (Lloyd et al. 1997; Wallrath 1998).

Recent work by Lemos et al. (2008) has shown that the modulating effect of cryptic Y chromosome polymorphisms on gene expression is pervasive throughout the D. melanogaster genome. Accordingly, males differing only in the origin of their Y chromosome showed differential expression at hundreds of non-Y-linked genes. Interestingly, many of these genes have male-biased expression and seem to be involved in species divergence and temperature adaptation. These results provided a molecular framework for how the Y chromosome affects adaptive phenotypic variation and fitness (Voelker and Kojima 1971; Chippindale and Rice 2001; Rohmer et al. 2004).

The role of genetic background on Y-linked regulatory variation (YRV) remains to be addressed. Previous experiments by Lemos et al. (2008) placed Y chromosomes in the genetic background of an inbred, homogeneous laboratory strain (B4361). This laboratory strain was chosen to ensure uniformity of genetic background. However, autosomal and X-chromosome polymorphisms occurring in natural populations may lend themselves to subtle modifications by cryptic Y-linked regulatory polymorphisms. In accordance with this possibility, Chippindale and Rice (2001) found significant background-by-Y interaction effects on male fitness. In addition, no studies have yet investigated the physical clustering of the genes affected by YRV along chromosomes.

This study is aimed at addressing the following questions: (i) Which genes show regulatory modulation due to Y-by-background effects? (ii) Which functional categories do these genes fall into? (iii) Do the genes affected by YRV show distinctive physical clustering patterns along autosomes or X chromosome? And (iv) is PEV differentially modulated by specific Y-by-background combinations? The Y chromosomes chosen were sampled from a tropical (India) and temperate (France) population of D. melanogaster. Flies from these populations have previously been shown to have major differences in their ability to carry out spermatogenesis under heat stress, in large part due to polymorphic variation between their Y chromosomes (Rohmer et al. 2004). Here we test the effect of the Y chromosomes on gene expression not only in the genetic background of an inbred laboratory strain, but also in the genetic background of both the tropical and temperate populations from which the Y chromosomes were derived. This experimental design allowed us to address the extent to which the expression of polymorphic Y-linked variation depends on the subtleties of genomic background. A gene-density plotting algorithm was used to test for physical clustering of genes showing YRV. Finally, both naturally occurring Y chromosomes were assayed for polymorphisms capable of regulating PEV.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Fly strains:

Wild flies were collected from Draveil, France (in 2001) and Delhi, India (in 1997) by members of Jean R. David's research group (Rohmer et al. 2004) and generously provided to us for analysis. For each population, wild-collected females were isolated in culture vials, and isofemale lines established. These lines (a minimum of 10) were eventually pooled to make a mass culture. Approximately 100 males per population were drawn from mass culture for crosses (supporting information, Figure S1), which allowed Y chromosomes from the French population to be introgressed into an otherwise Indian autosomal and X-chromosomal background, and vice versa. Y chromosomes from both populations were also introgressed into the same laboratory genetic background (B4361) used by Lemos et al. (2008). Hence, six strains were used for analysis. These consisted of the original French and Indian lines with their native Y chromosomes, namely, French background with French Y chromosome (French: YF), and Indian background with Indian Y chromosome (Indian: YI). In addition we studied four Y-substituted strains, namely, Indian genetic background with French Y chromosome (Indian: YF), laboratory background with French Y chromosome (B4361: YF), France background with Indian Y chromosome (French: YI), and laboratory background with Indian Y chromosome (B4361: YI). Males from these strains were collected for use in microarray dye-swap experiments. Newly emerged males were collected on the 10th day after egg laying and allowed to age for 3 days at 25°, after which they were flash frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°.

All crosses for each Y-substitution line were carried out with 10–15 vials with multiple mating pairs per vial. Gene expression differences between males were assayed in flies grown under carefully controlled environments—24 hr light, 25°, and constant humidity—and harboring naturally occurring Y chromosome variants.

Microarray hybridizations and analysis:

Our experimental design consisted of 16 cDNA microarrays, 4–6 for each of the three backgrounds (French, Indian, and B4361), involving 32 separate labeling reactions. We contrasted two Y chromosomes (YI and YF) on each microarray. Microarrays were ∼18,000-feature cDNA arrays spotted with D. melanogaster cDNA PCR products as described (Lemos et al. 2008). RNA extraction, cDNA synthesis, microarray hybridization, and microarray slide scanning protocols closely followed that of Lemos et al. (2008). Foreground fluorescence of dye intensities was normalized by the Loess method implemented in the library Limma of the statistical software R. Microarray gene expression data herein reported can be obtained at the GEO database (GSE21587).

Significance of variation in gene expression in each background due only to the Y chromosome was assessed using the Bayesian analysis of gene expression levels (BAGEL) algorithm (Townsend and Hartl 2002). False discovery rates (FDR) were estimated empirically on the basis of the variation observed when randomized versions of the original data set were analyzed. Density along chromosomes of genes showing Y-linked regulatory variation as assessed by BAGEL was plotted using a sliding-window algorithm with window size of 2 Mb, sliding in 1-Mb increments. Confidence intervals were estimated empirically by running the density-plotting algorithm on 1000 sets of randomly sampled genes taken from the genome as a whole as represented by features on the microarray, with gene number equal to the number of differentially expressed genes. Cutoff 95% densities were plotted, and any clusters with observed densities beyond these values were regarded as significant.

To test for the effect of Y-by-background interaction on gene expression, a linear model was fitted to normalized data: γij = μ + Bi + Yj + I(Background × Y)ij + eijk, where γij is the normalized-transformed gene expression, μ is the population mean, Bi is the effect of the ith genetic background, Yj is the effect of the jth Y chromosome, I(Background × Y)ij is the effect of background-by-Y interaction, and eijk is the residual effect. To test for agreement with the BAGEL results, a second model was implemented to test for Y-only effects: γij = μ + Yj + eijk, where Yj refers to YI or YF. The significance of effects from Y-only and background-by-Y interactions was tested by using the Fs-test, a modified F-statistic incorporating shrinkage variance components (Cui et al. 2005). P-values were calculated by performing 1000 permutations of samples and corrected for multiple hypotheses testing by the q-value false discovery rate method (Storey and Tibshirani 2003). Significant changes were determined at the FDR threshold of 0.01. A k-means analysis was used to identify groups of genes with similar expression patterns across Y-by-background groups. In the bootstrapped k-means algorithm, a gene was assigned to a group if it was identified in 80% of 1000 iterations. This was repeated for different values of k to find the k needed to minimize the number of genes not identified in any group. All analyses described in this paragraph were computed with the R/Maanova package (Wu et al. 2003).

Enrichment in gene ontology categories was assessed with GeneMerge (Castillo-Davis and Hartl 2003), which uses a hypergeometric distribution to assess significance. Because GeneMerge tests for all categories, a modified Bonferroni correction was used to account for multiple testing.

PEV:

Males from all four populations were crossed to females from a stock carrying w[m4h] (Figure S2). These females possess an inversion on the X chromosome that repositions the w[m4h] gene proximal to the X centromere. All flies were maintained at either 25° or 18°. Males from these crosses were collected, flash frozen in liquid nitrogen, aged for 3 days at either 25° or 18°, and stored at −80°. Heads of males were removed with a blade and homogenized five to a tube with 10 μl of acidified ethanol (30% ethanol acidified to pH 2 with HCl). Eye pigment expression was assessed with spectrophotometric analysis at an optical density of 480 nm. Four to six biological replicates were used per treatment, with two measurements taken per replicate. The correlation between repeat measures was high (Pearson's r = 0.90), and thus their means were used in subsequent analyses. Males displaying typical eye-pigmentation phenotypes were imaged using an automontage system (Snycroscopy, Frederick, MD). A three-way ANOVA analysis, using statistical software JMP, was performed using male background (Indian, French, or B4361), Y chromosome (YI or YF), and temperature (25° or 18°) as factors.

RESULTS

Global gene expression variation:

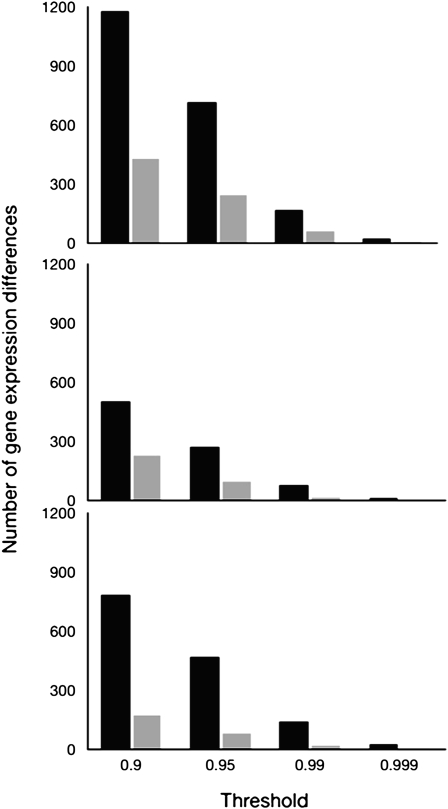

Males differing only in their Y chromosomes (either YI or YF) showed differential expression of a substantial number of genes, with the exact number depending on the genetic background interrogated and the cutoff for significance used (12–1178 genes when the Bayesian posterior probability is >0.999 or 0.90, corresponding to FDR of <1% or 35%, respectively) (Figure 1). For every genetic background, and at every significance cutoff value, the observed number of genes differentially expressed among YI and YF males exceeded the number expected by chance. Overlap of differentially expressed gene sets between the three different backgrounds is shown in Figure 2. The results suggest that although Y-linked regulatory polymorphisms have different modulating effects on genes depending on the genetic background of the male, there is some agreement on the genes showing YRV. All the following analyses are based on genes affected by YRV identified with a criterion of a Bayesian posterior probability >0.95.

Figure 1.—

Solid bars represent the number of genes differentially expressed by males possessing YI or YF in an Indian genetic background (top), a French genetic background (middle), or a B4361 genetic background (bottom), as a function of the Bayesian posterior probability of differential expression. Shaded bars indicate the estimated number of genes expected by chance.

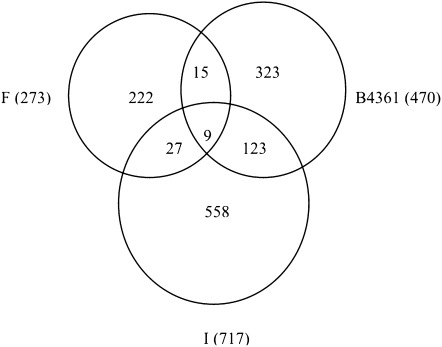

Figure 2.—

Venn diagrams showing the number of unique Y-regulated genes (Bayesian posterior probability >0.95) in Indian (I), French (F), and B4361 genetic backgrounds and overlap between affected genes in different backgrounds. The number of genes found to be significant in each individual background is given in parentheses.

Clustering of genes showing YRV into significant functional categories is listed in Table 1. Of note, pheromone binding and immune response genes are heavily represented, as well as genes localized to extracellular regions across all three backgrounds. This again suggests that genes showing YRV show a consistent pattern with respect to function.

TABLE 1.

Significantly overrepresented Gene Ontology categories for genes identified to be overexpressed in BAGEL analysis

| GO category | Description | Background and no. of genes |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | F | B4361 | ||

| Molecular function | ||||

| GO:0004252 | Serine-type endopeptidase activity | 14* | 4 | 3 |

| GO:0005550 | Pheromone binding | 5 | 6*** | 1 |

| GO:0008145 | Phenylalkylamine binding | 2 | 3* | 1 |

| GO:0004364 | Glutathione transferase activity | 10 | 7* | 1 |

| Biological processes | ||||

| GO:0006952 | Defense response | 47*** | 21* | 17 |

| GO:0009636 | Response to toxin | 19** | 11** | 4 |

| GO:0006508 | Proteolysis | 62*** | 18 | 24 |

| GO:0006961 | Antibacterial humoral response | 5 | 6* | 7 |

| GO:0019236 | Response to pheromone | 2 | 4* | 2 |

| Cellular component | ||||

| GO:0005576 | Extracellular region | 34*** | 19*** | 25* |

P-values are adjusted for multiple hypothesis testing. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

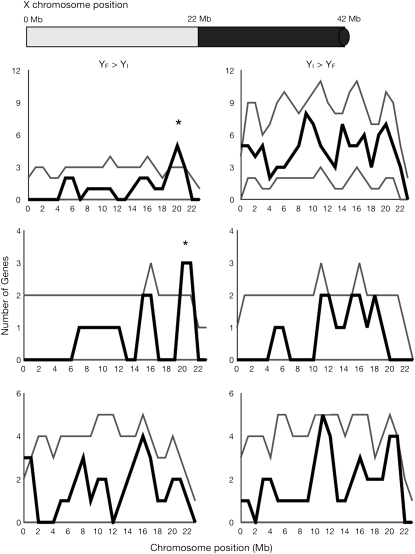

Physical clustering of genes along chromosomes was also examined. While no physical clustering is apparent in the autosomes, males possessing YF showed overexpression of genes near the euchromatin–heterochromatin boundary of the X chromosome (at chromosome position 22 Mb) as compared to males possessing YI (Figure 3). This pattern holds true in both the Indian and the French genetic backgrounds, but not in the B4361 genetic background. In the Indian background, five genes near the X chromosome euchromatin–heterochromatin boundary showed this pattern of overexpression in YF males compared to YI. Of these, one encodes a protein categorized as sensory perception of chemical stimulus, namely gene Obp19a encoding odorant-binding protein 19a. In the French genetic background, three genes near the X chromosome euchromatin–heterochromatin boundary showed this pattern. All three encode proteins involved in the sensory perception of chemical stimulus (Obp19a and Obp19b encoding odorant-binding proteins 19a and 19b, and Pbprp3 encoding pheromone-binding protein-related protein 3). The observed effect of the Y chromosome on modulating genes associated with pheromone binding and sensory perception has important implications for male fitness and sexual selection.

Figure 3.—

Clustering of genes showing YRV along the euchromatic portion of the X chromosome in an Indian genetic background (top), a French genetic background (middle), or a B4361 genetic background (bottom). Solid lines indicate observed density of genes around a 2-Mb sliding window (step size 1 Mb). Shaded lines indicate 95% confidence intervals. A schematic X chromosome is drawn at the top left with the shaded area representing euchromatin and the solid area representing heterochromatin. The solid knob at the right represents the X chromosome centromere. Columns represent genes for which males possessing YF showed enhanced expression over males possessing YI (YF > YI) or vice versa (YI > YF). An asterisk denotes a chromosomal segment containing significantly more genes showing Y-linked regulation than expected by chance.

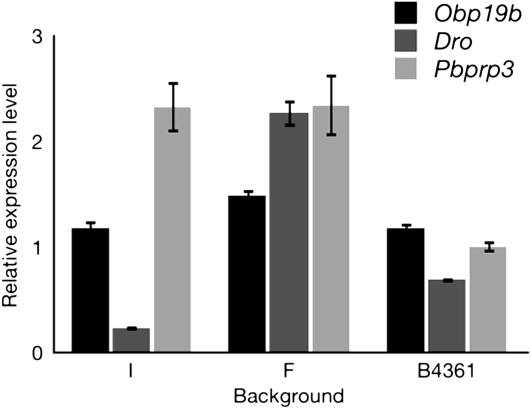

The relative expression levels of three representative genes showing YRV are plotted in Figure 4. One gene, Obp19b, was chosen because it is located near the X chromosome euchromatin–heterochromatin boundary and was also identified in both the French and the Indian backgrounds as being significantly overexpressed in YF compared to YI males. Two other genes, Dro (Drosocin) and Pbprp3 (pheromone-binding protein-related protein 3), were chosen because they belonged to biological clusters identified to be overrepresented in the YRV-regulated gene sets (immune response and pheromone binding, respectively). Ratios represent relative expression levels of genes in YF males over YI males in the three genetic backgrounds. The results show, again, how epistatic interactions between Y-linked polymorphisms and background can modulate the expression of non-Y-linked genes. Particularly striking is the differential relative expression of Dro, an immune response gene, in the three backgrounds: when comparing expression of Dro in YF males to that in YI males, it is underexpressed in the Indian background, overexpressed in the French background, and slightly underexpressed in the B4361 background.

Figure 4.—

Relative expression levels of three genes showing YRV in YF males vs. YI males in three genetic backgrounds (I, Indian; F, French; and B4361). Expression levels are shown as the ratio of YF over YI expression (±SE). Obp19a is an odorant-binding-protein gene near the X euchromatin–heterochromatin boundary. Drosocin (Dro) is an immune-response gene. Pbprp3 encodes pheromone-binding protein-related protein 3, a pheromone-binding protein.

Extensive Y-by-background interaction:

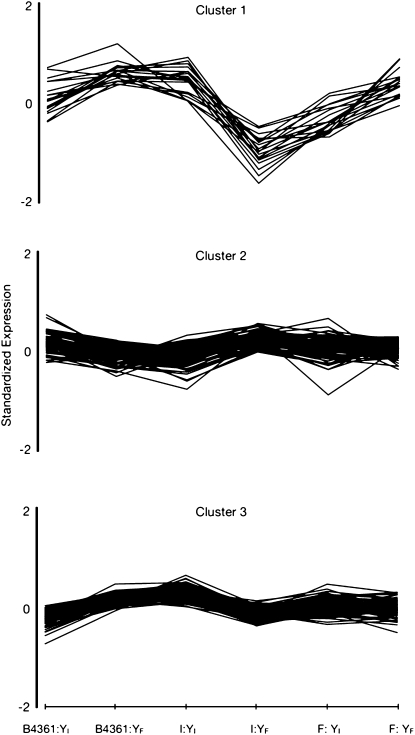

Y-by-background effects, as assessed by the Maanova linear model, influenced the expression of 346 genes (FDR < 0.01). Agreement between these results and the BAGEL results is strong: 252 (74%) of the 346 genes were also identified by BAGEL as differentially regulated by Y-linked polymorphisms in at least one of the genetic backgrounds (B4361, Indian, or French) (Table S1). Two hundred (57.8%) of the 346 genes can be grouped most parsimoniously into three clusters of gene expression (Figure 5). In each cluster, genes show similar patterns of high expression in some Y-background combinations and low expression in others. Significant Gene Ontology categories within each cluster are listed in Table 2. In both methods of analysis (BAGEL and Maanova), immune response genes are heavily represented within significantly differentially expressed genes.

Figure 5.—

Gene expression profiles generated by k-means clustering. Each line represents the expression of one gene across each background-by-Y group. Expression measures were standardized across groups and analyzed using k-means cluster analysis. There are 19, 88, and 93 genes in clusters 1, 2, and 3, respectively.

TABLE 2.

Significantly overrepresented functional Gene Ontology categories for gene expression clusters as identified by Maanova for Y-by-background effects

| Cluster | GO category | Description | No. of genes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | GO:0006961 | Antibacterial humoral response (sensu Protostomia) | 6*** |

| 1 | GO:0042742 | Defense response to bacterium | 4*** |

| 1 | GO:0050829 | Defense response to gram-negative bacterium | 3*** |

| 1 | GO:0050830 | Defense resonse to gram-positive bacterium | 2** |

| 1 | GO:0001501 | Skeletal development | 2** |

| 1 | GO:0005975 | Carbohydrate metabolic process | 3* |

| 2 | GO:0019236 | Response to pheromone | 3** |

| 2 | GO:0045861 | Negative regulation of proteolysis | 2* |

| 3 | GO:0009405 | Pathogenesis | 2* |

| 3 | GO:0006631 | Fatty acid metabolic process | 4* |

P-values are adjusted for multiple hypothesis testing. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

Y chromosome main effects, as identified by Maanova, regulate the differential expression of 192 genes. A proper comparison with BAGEL results called for reanalysis of global gene expression patterns across all arrays (regardless of genetic background) using BAGEL. When this was done, 484 genes showed differential gene expression (Bayesian posterior probability >0.95). Of the 192 genes identified by Maanova, 106 (55%) of them were also identified in the BAGEL gene set, while 86 (45%) were not. The 86 novel targets of YRV are not surprising in view of our results indicating strong epistatic Y-by-background effects on gene expression. Such genes can fail to be identified by BAGEL because genes that are highly modulated by the Y chromosome in one genetic background but less so in others might show no consistent difference in expression between the temperate and tropical Y chromosomes when averaged across all genetic backgrounds.

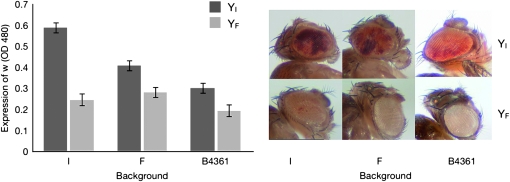

Polymorphic Y chromosome effects on position-effect variegation:

The above results from microarray data suggesting large Y-by-background interaction effects on gene expression, as well as clustering of these effects near the X chromosome euchromatin–heterochromatin boundary, were confirmed with a PEV assay. Males in the assay possessed either a YI or a YF in a hybrid genetic background consisting of white-eye mutation w[m4h] positioned near the X chromosome euchromatin–heterochromatin boundary; a haploid autosomal genome sampled from the original stock containing the PEV marker; and a haploid autosomal genome sampled from the Indian, French, or B4361 laboratory populations. The results suggest that temperature does not affect suppression of PEV (P = 0.26). This result is surprising, as previous studies have shown that high temperatures during development suppress PEV, while low temperatures enhance PEV (Spofford 1976; Zhang and Stankiewicz 1998). There were also no significant temperature-interaction factors (temperature × Y chromosome, P = 0.92; temperature × genetic background, P = 0.41; temperature × background × Y chromosome, P = 0.73). On the other hand, YI and YF differed dramatically in their effects on position-effect variegation (Figure 6, P < 0.0001), with YI males showing broader expression of w[m4h] than YF in all genetic backgrounds; however, the effect is least pronounced in the B4361 background. Also importantly, genetic background showed a significant effect on PEV (P < 0.0001), with a similarly significant effect for Y-by-background interaction (P < 0.001). These results suggest that the modulation of PEV, which is caused by the mosaic expression of w[m4h], a gene positioned near the X chromosome euchromatin–heterochromatin boundary, is sensitive to epistatic interactions between the Y chromosome and genetic background. These results are therefore in agreement with the findings from our genome-wide gene expression assay.

Figure 6.—

Y-chromosome effects on position-effect variegation (PEV). YI suppresses PEV more and thus allows more expression of w[m4h] than YF in all three genetic backgrounds (I, Indian; F, French; and B4361). Eye pigmentation was measured as absorption of light at 480 nm. Pictures of heads of representative male flies are shown to the right.

DISCUSSION

The data presented here suggest that polymorphic variation in Y chromosomes from two geographically diverse D. melanogaster populations differentially regulate the expression of hundreds of autosomal and X-linked genes. However, the contribution of Y chromosomes to global expression profiles depends on the genetic background of the bearer. Accordingly, we observed that the contribution of a temperate or a tropical Y chromosome to global gene expression is most pronounced when males differing only in the origin of their Y chromosomes are assayed in their wild-type naturally occurring genetic backgrounds: Y chromosome substitution lines in the Indian background showed more than twice the number of differentially expressed genes than Y chromosome substitution lines in the French background. This study also presents new data suggesting the physical clustering of genes exhibiting YRV. We found significant physical and functional clustering around the euchromatin–heterochromatin boundary of the X chromosome, with X-linked olfaction-related genes showing higher transcription levels in males with YF than in males with YI. Finally, the Y-by-background interaction effects on autosomal and X-linked gene expression, as well as the existence of polymorphic variation between the two Y chromosomes in their effects on modulating genes proximal to the euchromatin–heterochromatin boundary in the X chromosome, were confirmed with a position-effect variegation assay.

Y-linked genetic variation has been previously documented for sex ratio (Carvalho et al. 1997; Montchamp-Moreau et al. 2001), male courtship (Huttunen and Aspi 2003), geotaxis (Stoltenberg and Hirsch 1997), thermal sensitivity of spermatogenesis (Rohmer et al. 2004), and fitness (Chippindale and Rice 2001). For many of these traits (male courtship, geotaxis, spermatogenesis, and fitness), significant Y-by-background interaction effects have also been detected. Thus, our observations regarding substantial Y-by-background interaction for gene expression traits are in good agreement with these previous findings regarding higher-level phenotypes.

These findings of Y chromosome effects on male phenotypes contrast with molecular analyses showing no polymorphism among 11 alleles of a 1738-bp region of a Y-linked gene in D. melanogaster (Zurovcova and Eanes 1999). In humans, Y-linked genes also show decreased levels of molecular variation, with a large-scale analysis of four Y-linked genes finding that coding regions show between 0 and 20% of the polymorphism of a sample of autosomal genes (Shen et al. 2000; Rozen et al. 2009). Despite the lack of nucleotide diversity in coding sequences of Y-linked genes, considerable structural polymorphism has been detected in the copy numbers of Y-linked heterochromatin repeats in humans and flies (Lyckegaard and Clark 1989, 1991; Karafet et al. 1998; Repping et al. 2003). Repeat sites have been shown to act as nucleation sites for heterochromatin formation via the RNAi pathway (Dorer and Henikoff 1994; Volpe et al. 2002; Elgin and Grewal 2003; Pal-Bhadra et al. 2004).

Heterochromatin can influence transcription epigenetically, with the effect most easily observed in the modification of PEV by the Y chromosome (Dimitri and Pisano 1989; Dorer and Henikoff 1994). Large heterochromatic blocks, such as the Y chromosome, are thought to sequester limiting heterochromatin factors from other regions, thus impeding the spread of heterochromatin to nearby loci (Lloyd et al. 1997; Schulze and Wallrath 2007). In this way, silencing of genes located near heterochromatin–euchromatin boundaries is suppressed. Balanced polymorphisms in Y chromosome heterochromatin repeats may provide the necessary molecular variation for differential competitive binding ability of chromatin proteins. The concomitant redistribution of chromatin proteins will most strongly influence the expression of genes located next to other heterochromatic blocks, such as at euchromatin–heterochromatin boundaries. An alternate explanation for the influence of the Y chromosome on PEV is via the Y chromosome's effect on RNA-interference pathways. The spread of heterochromatin is initiated through the transcription of repeat DNA and then propagated via the RNA-interference pathway. Lemos et al. (2008) found Y-linked polymorphisms responsible for the differential expression of transposable elements, which are known to undergo RNAi-mediated silencing. Therefore, mechanistic similarities underlying Y-linked effects on gene expression and PEV may exist.

The acrocentric X chromosome of D. melanogaster is partitioned into 22 Mb of distal euchromatin and 20 Mb of proximal heterochromatin (Adams et al. 2000). As our results suggest, many of the genes showing Y-linked regulatory variation near the euchromatin–heterochromatin boundary in the X chromosome are odorant-binding proteins, which are components of the insect olfactory system (Wang et al. 2009). Odorant receptors are rapidly evolving molecules in the Drosophila proteome (Robertson et al. 2003) and show altered expression following mating (McGraw et al. 2004). Interestingly, the genes affected by Y-linked regulatory elements exhibit significant functional coherence in showing association with pheromone detection. The influence of the Y chromosome on pheromone detection as well as odorant-binding proteins suggests a role for the Y chromosome in mating behavior and may help to explain the cessation of rigorous courtship and the reduced mating success of XO Drosophila males (Cordts and Partridge 1996; Kuijper et al. 2006). In Anopheles mosquitoes, the Y chromosome has also been implicated in influencing mating behavior (Fraccaro et al. 1977). Because many mating-behavior-related proteins are selected for in different ways in males and females, there may be selection for sex limitation of modifiers of their expression. Since the Y chromosome is male limited, it serves as the perfect platform for these modifiers. Lemos et al. (2008) showed that genes showing Y-linked regulatory variation are more highly expressed in males than in females, suggesting that the recruitment of modifiers of male-biased genes may have shaped the evolution of the Y chromosome.

In addition to pheromone-binding proteins, genes showing Y-linked regulatory variation are also associated with immune response and are more likely to be localized to the extracellular matrix than expected by chance. Although there are no previous studies of Y chromosome effects on immune response genes in Drosophila, studies in mice have found that Y-linked polymorphisms are capable of modifying autoimmune disease susceptibility (Teuscher et al. 2006; Spach et al. 2009). However, in mice, several genes of immunologic significance are located on the Y and may serve as candidates for explaining the effect. In Drosophila, no Y-linked immune-related genes are known. Therefore we suggest that our findings of Drosophila immune response genes being responsive to YRV are most likely explained by variation in noncoding components of the Y chromosome, such as repeat copy number. D. melanogaster populations from France and India are known to differ in the thermal sensitivity of spermatogenesis (Rohmer et al. 2004; David et al. 2005), with temperate and tropical Y chromosomes contributing substantially to this difference. Among genes that show YRV in at least two of the three backgrounds, we find candidates known to be structural constituents of cytoskeleton (nod, CG9279, and tm2) and lipid metabolism (CG9914, CG17292, CG9458, CG11426, CG6295, CG6277, CG18815, and CG31872). In addition, fatty acid metabolism genes are overrepresented in one of the clusters detected by k-means analysis using Maanova. This suggests that, while the heat sensitivity of spermatogenesis expresses itself sharply at higher temperatures, the modulating effects of the Y chromosome on sperm-related traits may be subtle at permissive or less stressful temperatures. Finally, localization of genes showing YRV to extracellular regions is expected, as many pheromone-binding proteins and proteins involved in immune response are receptor proteins with large extracellular domains.

In summary, our finding of cryptic Y-linked regulatory control of hundreds of genes across various genetic backgrounds suggests standing Y-linked balanced polymorphisms in natural populations. At a cursory glance, this result seems incongruent with previous theoretical and empirical work suggesting little Y-linked polymorphism can be supported in a nonrecombining chromosome. However, our findings, together with other studies of the nontransitivity of sperm competition and Y-by-background interactions for male fitness (Clark et al. 2000; Chippindale and Rice 2001), bring to light some complex and previously underappreciated dynamics for maintaining Y-linked polymorphisms.

Acknowledgments

We thank Jean R. David and the Bloomington Stock Center for stocks; members of the Hartl lab for their insightful suggestions; and Mauricio Carneiro, Rebekah Rogers, and Hsiao-Han Chang for help in some of the data analyses. P.-P.J. is supported in part by a fellowship from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada. This research was supported by National Institutes of Health grant GM084236 to D.L.H.

Supporting information is available online at http://www.genetics.org/cgi/content/full/genetics.110.118109/DC1.

References

- Adams, M. D., S. E. Celniker, R. A. Holt, C. A. Evans, J. D. Gocayne et al., 2000. The genome sequence of Drosophila melanogaster. Science 287 2185–2195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bachtrog, D., E. Hom, K. M. Wong, X. Maside and P. de Jong, 2008. Genomic degradation of a young Y chromosome in Drosophila miranda. Genome Biol. 9 R30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bull, J. J., 1983. Evolution of Sex Determination Mechanisms. Benjamin Cummings, Menlo Park, CA.

- Carvalho, A. B., and A. G. Clark, 2005. Y chromosome of D. pseudoobscura is not homologous to the ancestral Drosophila Y. Science 307 108–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho, A. B., S. C. Vaz and L. B. Klaczko, 1997. Polymorphism for Y-linked suppressors of sex-ratio in two natural populations of Drosophila mediopunctata. Genetics 146 891–902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho, A. B., B. P. Lazzaro and A. G. Clark, 2000. Y chromosomal fertility factors kl-2 and kl-3 of Drosophila melanogaster encode dynein heavy chain polypeptides. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97 13239–13244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho, A. B., B. A. Dobo, M. D. Vibranovski and A. G. Clark, 2001. Identification of five new genes on the Y chromosome of Drosophila melanogaster. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98 13225–13230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho, A. B., L. B. Koerich and A. G. Clark, 2009. Origin and evolution of Y chromosomes: Drosophila tales. Trends Genet. 25 270–277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castillo-Davis, C. I., and D. L. Hartl, 2003. GeneMerge—post-genomic analysis, data mining, and hypothesis testing. Bioinformatics 19 891–892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chakir, M., A. Chafik, B. Moreteau, P. Gibert and J. R. David, 2002. Male sterility thermal thresholds in Drosophila: D. simulans appears more cold-adapted than its sibling D. melanogaster. Genetica 114 195–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charlesworth, B., and D. Charlesworth, 2000. The degeneration of Y chromosomes. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 355 1563–1572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chippindale, A. K., and W. R. Rice, 2001. Y chromosome polymorphism is a strong determinant of male fitness in Drosophila melanogaster. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98 5677–5682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark, A. G., E. T. Dermitzakis and A. Civetta, 2000. Nontransitivity of sperm precedence in Drosophila. Evolution 54 1030–1035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cordts, R., and L. Partridge, 1996. Courtship reduces longevity of male Drosophila melanogaster. Anim. Behav. 52 269–278. [Google Scholar]

- Cui, X., J. T. Hwang, J. Qiu, N. J. Blades and G. A. Churchill, 2005. Improved statistical tests for differential gene expression by shrinking variance components estimates. Biostatistics 6 59–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- David, J. R., L.O. Araripe, M. Chakir, H. Legout, B. Lemos et al., 2005. Male sterility at extreme temperatures: a significant but neglected phenomenon for understanding Drosophila climatic adaptations. J. Evol. Biol. 18 838–846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimitri, P., and C. Pisano, 1989. Position effect variegation in Drosophila melanogaster: relationship between suppression effect and the amount of Y chromosome. Genetics 122 793–800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorer, D. R., and S. Henikoff, 1994. Expansions of transgene repeats cause heterochromatin formation and gene silencing in Drosophila. Cell 77 993–1002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elgin, S. C. R., and S. I. S. Grewal, 2003. Heterochromatin: silence is golden. Curr. Biol. 13 R895–R898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraccaro, M., L. Tiepolo, U. Laudani, A. Marchi and S. D. Jayakar, 1977. Y chromosome controls mating behaviour in Anopheles mosquitos. Nature 265 326–328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gatti, M., and S. Pimpinelli, 1992. Functional elements in Drosophila melanogaster heterochromatin. Annu. Rev. Genet. 26 239–275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes, J. F., H. Skaletsky, T. Pyntikova, T. A. Graves, S. K. van Daalen et al., 2010. Chimpanzee and human Y chromosomes are remarkably divergent in structure and gene content. Nature 7280 536–539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huttunen, S., and J. Aspi, 2003. Complex inheritance of male courtship song characters in Drosophila virilis. Behav. Genet. 33 17–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karafet, T., P. de Knijff, E. Wood, J. Ragland, A. G. Clark et al., 1998. Different patterns of variation at the X- and Y-chromosome-linked microsatellite loci DXYS156X and DXYS156Y in human populations. Hum. Biol. 70 979–992. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koerich, L. B., X. Wang, A. G. Clark and A. B. Carvalho, 2008. Low conservation of gene content in the Drosophila Y chromosome. Nature 7224 949–951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krsticevic, F. J., H. L. Santos, S. Januario, C. G. Schrago and A. B. Carvalho, 2010. Functional copies of the Mst77F gene on the Y chromosome of Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics 184 295–307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuijper, B., A. D. Stewart and W. R. Rice, 2006. The cost of mating rises nonlinearly with copulation frequency in a laboratory population of Drosophila melanogaster. J. Evol. Biol. 19 1795–1802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemos, B., L. O. Araripe and D. L. Hartl, 2008. Polymorphic Y chromosomes harbor cryptic variation with manifold functional consequences. Science 319 91–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd, V. K., D. A. Sinclair and T. A. Grigliatti, 1997. Competition between different variegating rearrangements for limited heterochromatic factors in Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics 145 945–959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyckegaard, E. M. S., and A. G. Clark, 1989. Ribosomal DNA and stellate gene copy number variation on the Y-chromosome of Drosophila melanogaster. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 86 1944–1948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyckegaard, E. M. S., and A. G. Clark, 1991. Evolution of ribosomal-RNA gene copy number on the sex-chromosomes of Drosophila melanogaster. Mol. Biol. Evol. 8 458–474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGraw, L. A., G. Gibson, A. G. Clark and M. F. Wolfner, 2004. Genes regulated by mating, sperm, or seminal proteins in mated female Drosophila melanogaster. Curr. Biol. 14 1509–1514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montchamp-Moreau, C., V. Ginhoux and A. Atlan, 2001. The Y chromosomes of Drosophila simulans are highly polymorphic for their ability to suppress sex-ratio drive. Evolution 55 728–737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller, H. J., 1930. Types of visible variations induced by X-rays in Drosophila. J. Genet. 22 299–335. [Google Scholar]

- Pal-Bhadra, M., B. A. Leibovitch, S. G. Gandhi, M. Rao, U. Bhadra et al., 2004. Heterochromatic silencing and HP1 localization in Drosophila are dependent on the RNAi machinery. Science 303 669–672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Repping, S., H. Skaletsky, L. Brown, S. K. M. van Daalen, C. M. Korver et al., 2003. Polymorphism for a 1.6-Mb deletion of the human Y chromosome persists through balance between recurrent mutation and haploid selection. Nat. Genet. 35 247–251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rice, W. R., 1987. Genetic hitchhiking and the evolution of reduced genetic activity of the Y sex chromosome. Genetics 116 161–167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson, H. M., C. G. Warr and J. R. Carlson, 2003. Molecular evolution of the insect chemoreceptor gene superfamily in Drosophila melanogaster. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100 14537–14542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohmer, C., J. R. David, B. Moreteau and D. Joly, 2004. Heat induced male sterility in Drosophila melanogaster: adaptive genetic variations among geographic populations and role of the Y chromosome. J. Exp. Biol. 207 2735–2743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rozen, S., J. D. Marzalek, R. K. Alagappan, H. Skaletsky and D. C. Page, 2009. Remarkably little variation in proteins encoded by the Y chromosome's single-copy genes, implying effective purifying selection. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 85 923–928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulze, S. R., and L. L. Wallrath, 2007. Gene regulation by chromatin structure: paradigms established in Drosophila melanogaster. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 52 171–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen, P. D., F. Wang, P. A. Underhill, C. Franco, W. H. Yang et al., 2000. Population genetic implications from sequence variation in four Y chromosome genes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97 7354–7359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spach, K. M., M. Blake, J. Y. Bunn, B. McElvany, R. Noubade et al., 2009. Cutting edge: the Y chromosome controls the age-dependent experimental allergic encephalomyelitis sexual dimorphism in SJL/J mice. J. Immunol. 182 1789–1793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spofford, J. B., 1976. Position-effect variegation in Drosophila, pp. 955–1018 in The Genetics and Biology of Drosophila, Vol. 1c, edited by M. Ashburner and E. Novitiski. Academic Press, New York.

- Stoltenberg, S. F., and J. Hirsch, 1997. Y-chromosome effects on Drosophila geotaxis interact with genetic or cytoplasmic background. Anim. Behav. 53 853–864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storey, J. D., and R. Tibshirani, 2003. Statistical significance of genomewide studies. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100 9440–9445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talbert, P. B., and S. Henikoff, 2006. Spreading of silent chromatin: inaction at a distance. Nat. Rev. Genet. 7 793–803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teuscher, C., R. Noubade, K. Spach, B. McElvany, J. Y. Bunn et al., 2006. Evidence that the Y chromosome influences autoimmune disease in male and female mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 103 8024–8029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Townsend, J. P., and D. L. Hartl, 2002. Bayesian analysis of gene expression levels: statistical quantification of relative mRNA level across multiple strains or treatments. Genome Biol. 3 R0071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vibranovski, M. D., L. B. Koerich and A. B. Carvalho, 2008. Two new Y-linked genes in Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics 179 2325–2327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voelker, R. A., and K. Kojima, 1971. Fertility and fitness of XO males in Drosophila. I. Qualitative study. Evolution 25 119–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volpe, T. A., C. Kidner, I. M. Hall, G. Teng, S. I. S. Grewal et al., 2002. Regulation of heterochromatic silencing and histone H3 lysine-9 methylation by RNAi. Science 297 1833–1837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallrath, L. L., 1998. Unfolding the mysteries of heterochromatin. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 8 147–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, P., R. F. Lyman, T. F. C. Mackay and R. R. H. Anholt, 2009. Natural variation in odorant recognition among odorant binding proteins in Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics 184 759–767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu, H., M. K. Kerr, X. Q. Cui and G. A. Churchill, 2003. MAANOVA: a software package for the analysis of spotted cDNA microarray experiments, pp. 313– 431 in The Analysis of Gene Expression Data: An Overview of Methods and Software, edited by G. Parmgiani, E. S. Garrett, R. A. Irizarry and S. L. Zeger. Springer, New York.

- Zhang, P., and R. L. Stankiewicz, 1998. Y-linked male sterile mutations induced by P element in Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics 150 735–744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zurovcova, M., and W. F. Eanes, 1999. Lack of nucleotide polymorphism in the Y-linked sperm flagellar dynein gene Dhc-Yh3 of Drosophila melanogaster and D. simulans. Genetics 153 1709–1715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]