Abstract

In the developing nervous system, cohorts of events regulate the precise patterning of axons and formation of synapses between presynaptic neurons and their targets. The conserved PHR proteins play important roles in many aspects of axon and synapse development from C. elegans to mammals. The PHR proteins act as E3 ubiquitin ligases for the dual-leucine-zipper-bearing MAP kinase kinase kinase (DLK MAPKKK) to regulate the signal transduction cascade. In C. elegans, loss-of-function of the PHR protein RPM-1 (Regulator of Presynaptic Morphology-1) results in fewer synapses, disorganized presynaptic architecture, and axon overextension. Inactivation of the DLK-1 pathway suppresses these defects. By characterizing additional genetic suppressors of rpm-1, we present here a new member of the DLK-1 pathway, UEV-3, an E2 ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme variant. We show that uev-3 acts cell autonomously in neurons, despite its ubiquitous expression. Our genetic epistasis analysis supports a conclusion that uev-3 acts downstream of the MAPKK mkk-4 and upstream of the MAPKAPK mak-2. UEV-3 can interact with the p38 MAPK PMK-3. We postulate that UEV-3 may provide additional specificity in the DLK-1 pathway by contributing to activation of PMK-3 or limiting the substrates accessible to PMK-3.

CHEMICAL synapses are specialized cellular junctions that enable neurons to communicate with their targets. An electrical impulse causes calcium channel opening and consequently stimulates synaptic vesicles in the presynaptic terminals to fuse at the plasma membrane. Neurotransmitter activates receptors on the postsynaptic membrane and triggers signal transduction in the target cell. For this communication to occur efficiently, the organization of the proteins within these juxtaposed pre- and postsynaptic terminals must be tightly regulated (Jin and Garner 2008). Previous studies in Caenorhabditis elegans have identified RPM-1, a member of the conserved PHR (Pam/Highwire/RPM-1) family of proteins, as an important regulator for the synapse (Schaefer et al. 2000; Zhen et al. 2000). Recent functional studies of other PHR proteins have shown that they are also required for a number of steps during nervous system development including axon guidance, growth, and termination (Wan et al. 2000; D'souza; et al. 2005; Bloom et al. 2007; Grill et al. 2007; Lewcock et al. 2007; Li et al. 2008).

The signaling cascades regulated by the PHR proteins have been identified using genetic modifier screens (Diantonio et al. 2001; Liao et al. 2004; Nakata et al. 2005; Collins et al. 2006) and biochemical approaches (Grill et al. 2007; Wu et al. 2007). These studies reveal that a major function of PHR proteins is to act as ubiquitin E3 ligases (Jin and Garner 2008). In C. elegans, RPM-1 (Regulator of Presynaptic Morphology-1) regulates the abundance of its substrate, the dual-leucine-zipper-bearing MAP kinase kinase kinase (DLK MAPKKK), and controls the activity of the MAP kinase cascade composed of three additional kinases, MAPKK MKK-4, p38 MAPK PMK-3, and MAPKAPK MAK-2 (Nakata et al. 2005; Yan et al. 2009). This signaling cascade further regulates the activity of the CCAAT/enhancer binding protein (C/EBP), CEBP-1, via a mechanism involving 3′-UTR-mediated mRNA decay.

Signal transduction involving MAP kinases can be fine tuned using multiple mechanisms to ensure optimal signaling outputs (Raman et al. 2007). For example, scaffold proteins for MAP kinases can provide spatial regulation of kinase activation in response to different stimuli (Remy and Michnick 2004; Whitmarsh 2006). Small protein tags such as ubiquitin have also been shown to control the activation of kinases. Specifically, in the IKK pathway ubiquitination via Lys63 chain formation catalyzed by the Ubc13/Uev1a E2 complex and TRAF6 E3 ligase is required for TAK1 kinase activation (Skaug et al. 2009).

To further the understanding of the DLK-1 pathway in the development of the nervous system, we characterized a new complementation group of rpm-1(lf) suppressors. These mutations affect the gene uev-3, a ubiquitin E2 conjugating (UBC) enzyme variant (UEV). UEV proteins belong to the UBC family, but lack the catalytic active cysteine necessary for conjugating ubiquitin (Sancho et al. 1998). The best characterized UEV proteins are yeast Mms2 and mammalian Uev1A, both of which act as the obligatory partner for the active E2 Ubc13 and function in DNA repair and IKB pathways, respectively (Deng et al. 2000; Hurley et al. 2006). In addition, UEV proteins, such as Tsg101, can also regulate endosomal trafficking (Babst et al. 2000). We find that similar to other members of the DLK-1 pathway, uev-3 functions cell autonomously in neurons. uev-3 genetically acts downstream of mkk-4 and upstream of mak-2. UEV-3 can bind PMK-3 in heterologous protein interaction assays. We hypothesize that UEV-3 may add specificity to the DLK-1 pathway by binding to PMK-3 for its activation or for selecting specific downstream targets.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

C. elegans genetics:

C. elegans strains were maintained as described (Brenner 1974). The suppressors were isolated from rpm-1(ju44); syd-2(ju37); juIs1 or rpm-1(ju44); syd-1(ju82); juIs1 animals mutagenized with 50 mm EMS (Nakata et al. 2005). Suppressor mutations were outcrossed multiple times against wild-type (N2) or juIs1[Punc-25 SNB-1∷GFP] strains. Specificity of suppression of rpm-1(lf) was tested by crossing sup; rpm-1; syd-2; juIs1 to rpm-1; juIs1 males. Double mutants were constructed following standard procedures, and the genotypes were confirmed by allele-specific nucleotide alterations determined by DNA sequencing or restriction enzyme digest.

Cloning of uev-3:

We mapped the suppression activity of uev-3(ju587) in the rpm-1; syd-2 double mutant strain to chromosome I near +4 using the single-nucleotide polymorphism mapping strategy (Davis et al. 2005; Nakata et al. 2005). For fine mapping of uev-3 (ju587), we constructed dpy-5uev-3 (ju587) unc-75; rpm-1; juIs1 strain. Following crossing to the Hawaiian strain CB4856, recombinant animals of phenotypic Dpy non-Unc or Unc non-Dpy that were mutant for rpm-1 were selected, and the presence of uev-3 (ju587) in each recombinant was determined by observing juIs1 marker expression. uev-3 (ju587) was mapped between snp_F14B4[1] and snp_M04C9[1], within a 90-kb interval including about 19 predicted genes. We performed RNAi against the predicted genes using a sensitized strain eri-1(mg366); rpm-1(ju23); syd-2(ju37), and found that uev-3 RNAi caused suppression of rpm-1; syd-2 phenotypes. ju593, ju638, and ju639 were determined to be alleles of uev-3 on the basis of linkage to chromosome I and noncomplementation test. DNA sequence analyses of these suppressor mutations were carried out following standard procedures, and the nucleotide alterations were confirmed in independent PCR reactions.

Molecular biology and expression constructs:

We determined the gene structure and the full-length transcripts of uev-3 by RT–PCR and 5′-RACE analyses. Total RNAs were prepared using TRIzol reagents (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) according to the manufacturer's instructions, and cDNAs were generated using Superscript II reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). The 5′-RACE kit (Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis, IN) was used with the following pair of primers to amplify the 5′ region of uev-3: SP1 and YJ3861 ccattgacacgttgagattc and SP2 and YJ3846 acgtttagacactcctccc. DNA sequence analysis of eight cloned 5′-RACE products revealed a SL2 splice leader in all, indicating that uev-3 is transcribed as the downstream gene in the operon with rab-5. We obtained full-length uev-3 cDNA by RT–PCR using YJ3852 ggggacaagtttgtacaaaaaagcaggctccaaaatgtccgatcaacctgg and YJ3853 ggggaccactttgtacaagaaagctgggttatgaaattccaatgacatc. The DNA sequences of the cDNA clone (pCZ729) verified and corrected the predicted uev-3 exon and intron boundaries. The uev-3 expression constructs in C. elegans were generated following standard procedures or using Gateway Cloning Technology (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), and the details of the clones are in supporting information, Table S2. For yeast two-hybrid studies, full-length cDNA or fragments of cDNA for dlk-1, mkk-4, pmk-3, mak-2, or uev-3 were cloned either to pBTM116 vector to be expressed as GAL4 activation domain fusion protein or into pACT2 vector to be expressed as LexA DNA binding domain fusion protein, as described in Table S2. To generate pcDNA3-HA-uev-3 (pOF174), uev-3 cDNA was cloned into pcDNA3-HA-Gateway (pOF173) vector by Gateway system. To generate pFLAG-CMV-2-pmk-3 (pOF171), pmk-3 cDNA was cloned into pFLAG-CMV-2-Gateway (pOF169) vector by Gateway system. pFLAG-CMV-2-pmk-3 (AQF) (pOF175) was generated by PCR-based mutagenesis to change the TQY dual phosphorylation site to AQF.

Neuronal morphology and synapse analyses:

We observed GFP or SNB-1∷GFP using muIs32[Pmec-7-GFP] or juIs1[Punc-25-SNB-1∷GFP] in 1-day-old adult animals either live or anesthetized in 1% 1-phenoxy-2-propanol (TCI America, Portland, OR) in M9 buffer. Images were captured either on a Zeiss Axioplan 2 microscope with Chroma HQ filters or a Zeiss LSM510 confocal microscope.

Germline transformation and transgenic analyses:

Transgenic animals were usually generated by injecting DNA at a dilution series (1–50 ng/μl) following standard procedures (Mello et al. 1991), using either pRF4 rol-6(dm) or Pttx-3-RFP as coinjection markers. For each construct, 2 to 13 independent transgenic lines were analyzed.

Yeast two hybrid:

Yeast two-hybrid assays were performed using pACT2 and pBTM116 vector backbones (Clontech, Mountain View, CA). The yeast strain L40 [MATa his3D200 trp1-901 leu2-3, 112 ade2 LYS2∷(lex-Aop)4-HIS3 URA3∷(lexAop)8-lacZ GAL4 gal80] was used. The yeast transformation was performed by the lithium acetate method and selected on Trp-, Leu-, and His-selection plates. Pairs of plasmids were cotransformed into yeast strain L40, and selected on Leu–Trp plates. For interaction assay, single clones were picked from each transformation and cultured to OD600 = 1. Yeast cells were pelleted by centrifugation, washed three times and resuspended, and plated in a dilution series of 10 to 10000 times by pipeting 5 μl per spot onto Histidine selection plates containing 3mm 3-AT. β-Galactosidase assays were performed following the Clontech Yeast Protocols Handbook (Fields and Sternglanz 1994).

cebp-1 mRNA analysis by qRT–PCR:

RNA isolation and cDNA preparation were performed as above. Power SYBR Green PCR Master Mix kits (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) were used for the PCR reactions and the ABI Prism 7000 Sequence Detection system was used for real-time PCR. cDNAs were amplified using following primers: cebp-1 pair (gcacgacaagatgaagagg and gcatgcgttgctctttca) amplifies 183 bp; ama-1 pair (actcagatgacactcaacac and gaatacagtcaacgacggag) amplifies 128 bp.

Protein interaction studies in 293T mammalian cells:

Human embryonic kidney 293T cells were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum. Cells were transfected with a total of 5 μg of DNA containing various expression vectors. After 24 hr, cells were collected and washed once with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and lysed in 0.4 ml of 0.1% NP-40 lysis buffer (20 mm HEPES, pH 7.4, 150 mm NaCl, 1.5 mm MgCl2, 2 mm EGTA, 2 mm dithiothreitol, protease inhibitor, Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis, IN, and phosphatase inhibitor,Nacalai, San Diego, CA). Cellular debris was removed by centrifugation at 10,000 × g for 5 min. FLAG epitope-tagged proteins were immunoprecipitated with anti-FLAG monoclonal antibody M2 (Sigma, St. Louis, MO). For immunoblotting, aliquots of immunoprecipitates and whole-cell lysates were resolved on SDS–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS–PAGE), and transferred to Amersham Hybond-P membranes (GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ). The membranes were immunoblotted with anti-HA rabbit polyclonal antibody Y-11 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc., Santa Cruz, CA). The bound antibody was visualized with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated antibody to rabbit IgG using the Amersham ECL Advance Western blotting detection kit (GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ).

RESULTS

UEV-3 is a Ubc/E2 variant protein:

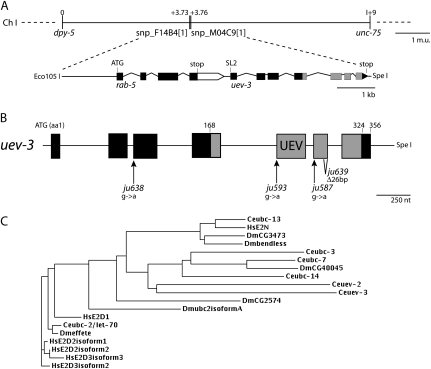

Previous analyses of the suppressors of rpm-1 loss-of-function (lf) mutants revealed five loci, defining dlk-1, mkk-4, pmk-3, mak-2, and cebp-1 (Nakata et al. 2005; Yan et al. 2009). We devised a noncomplementation test scheme and identified four alleles belonging to a new complementation group: ju593, ju587, ju638, and ju639. We mapped this suppressor locus to an interval of ∼90 kb on the right arm of chromosome I (Figure 1A). We used a combination of RNAi and transgenic expression of cosmid DNAs from the region to locate the gene affected. We found that the 6-kb Eco105I–SpeI fragment of the cosmid F26H9 contained the rescuing activity for the suppression of rpm-1(ju44) by ju587. The genomic DNA fragment contains two predicted genes: rab-5 and uev-3. By RT–PCR and 5′-RACE analyses, we determined that uev-3 transcripts contained an SL2 splice leader, confirming that rab-5 and uev-3 form an operon, with uev-3 as the downstream gene (materials and methods). DNA sequence analysis from ju587, ju593, and ju638 identified single nucleotide alteration at various splice acceptor sites, while ju639 is a 26-bp deletion from amino acid 277 in the sixth exon (Figure 1B and Table S1). Moreover, we performed RNAi of uev-3 in a sensitized genetic background and observed partial suppression of rpm-1(lf) (Table S1). These analyses are consistent with the suppressor mutations causing loss-of-function in uev-3.

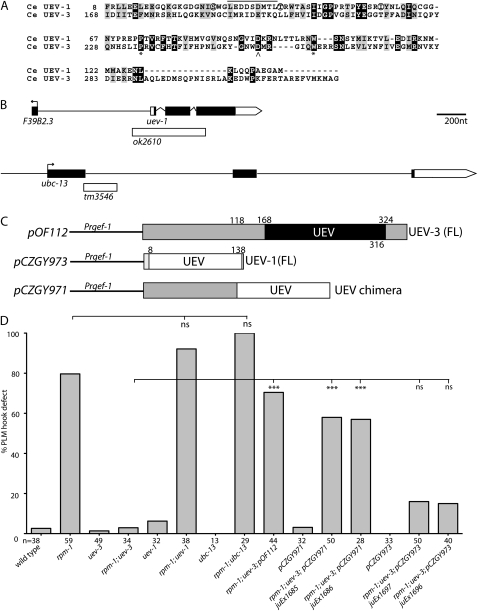

Figure 1.—

uev-3 is a ubiquitin E2 variant. (A) uev-3 locus on chromosome I. The Eco1051–SpeI genomic fragment from cosmid F26H9 fully rescues the suppression of rpm-1(lf) by uev-3 mutations. Solid box, coding sequences; open box, 3′ UTR; and lines, promoter or intronic sequences. (B) Illustration of uev-3 gene structure and positions of the mutations. Solid boxes, exons; and shading, UEV domain. (C) Dendrogram of UEV-3 with close homologs (ClustalW) Ce, C. elegans; Dm, Drosophila melanogaster, and Hs, Homo sapiens.

uev-3 is one of the three UEV proteins in C. elegans (Jones et al. 2002; Kipreos 2005). It is composed of 356 amino acids, with the UEV domain from residues 168 to 324 (Figure 1B). UEV proteins are similar to UBC E2 enzymes but lack the critical cysteine residue that is required for a transient interaction between E2 and ubiquitin (Sancho et al. 1998; Pickart and Eddins 2004) (Figure S1). Alignment of the UEV domain of UEV-3 with other UBC and UEV proteins reveals motifs with high similarity; for example, the HxN tripeptide motif, which is important for proper folding of the active site region in UBC proteins, is conserved in UEV-3 (Figure S1) (Gudgen et al. 2004). The overall sequence of UEV-3 is most similar to C. elegans UEV-2, followed by UBC-3 and UBC-7 in C. elegans (Figure 1C), and divergent from canonical UEVs (see below).

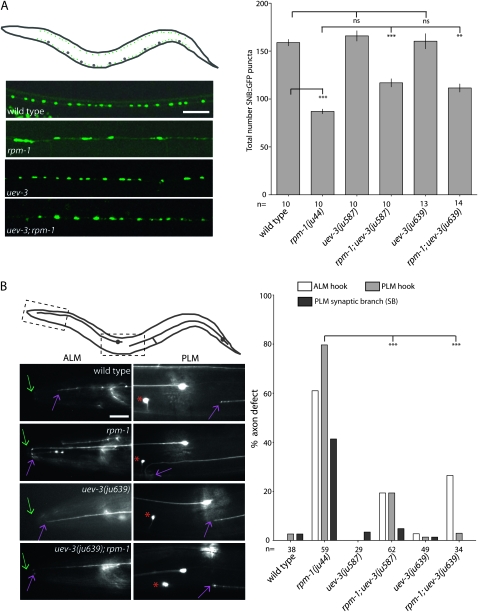

uev-3(lf) suppresses the defects in motor and mechanosensory neurons of rpm-1(lf):

rpm-1(lf) mutants display irregularly shaped and sized presynaptic terminals in the motor neurons (Zhen et al. 2000). The mutants also show axon termination defects in the mechanosensory neurons (Schaefer et al. 2000). Despite these defects, rpm-1(lf) animals appear superficially wild type in the overall nervous system architecture and locomotory behavior. The uev-3 mutants alone also develop normally and exhibit no discernable abnormalities in the motor and mechanosensory neurons (Figure 2). However, in an rpm-1(lf) background, mutations in uev-3 can ameliorate the defects in motor neuron synapses and touch axon patterning.

Figure 2.—

uev-3 suppresses rpm-1 defects in motor neuron synapse formation and mechanosensory neuron axon termination. (A) Top left schematic of an animal expressing Punc-25-SNB-1∷GFP (juIs1). Cell bodies (large gray dots) reside in the ventral cord, and synaptic SNB-1∷GFP puncta (small green dots) reside along the ventral and dorsal cords. The epifluorescent images below show SNB-1∷GFP in the dorsal cords in 1-day-old adult animals with genotypes as indicated. Scale bar, 10 μm. The graph on the right shows the quantification of SNB-1∷GFP in the dorsal cord (mean ±SEM). n indicates number of animals scored. Statistics, ANOVA with Bonferroni correction: (**) P< 0.01; (***) P < 0.001; (ns) not significant. (B) Schematic of animal expressing Pmec-7∷GFP (muIs32), marking one each of the bilaterally symmetric ALM and PLM neurons. Images below show portion of the ALM and PLM axons, corresponding to the dash-boxed regions. The tip of the animal's nose is indicated with green arrows, and ALM and PLM axon termination site is indicated with purple arrows. Red asterisks mark ALM cell body. ALM axon termination defects occur when the axon tip extends into the tip of the nose and loops back (or hook). PLM axon termination defects include absence of synapse branch or “hook” such that the PLM axon overextends beyond normal termination site and turns ventrally or turns ventrally before normal termination site. The graph shows the suppression of rpm-1 by uev-3 in three categories. n indicates animals scored. Statistics, Fischer exact test, comparing the PLM “hook” defects: (***) P < 0.001.

We determined the extent of rpm-1(lf) suppression by uev-3(lf). We first analyzed the presynaptic puncta patterns and numbers using juIs1 [Punc25-SNB-1∷GFP], a marker that visualizes presynaptic terminals in GABA motor neurons (Hallam and Jin 1998). In wild-type animals, this marker shows a pattern of uniformly sized and spaced fluorescent puncta along the dorsal and ventral cords, and on average, 158.9 puncta are visible in the dorsal cord (Figure 2A). rpm-1(lf) mutants have fewer puncta, averaging 87.1 puncta in the dorsal cord. The remaining GFP puncta in rpm-1 mutants are often enlarged and disorganized in distribution. Single mutants of uev-3(ju587) or uev-3(ju639) have an average 165.9 or 160.4 puncta per dorsal cord, respectively, and SNB-1∷GFP puncta patterns are similar to wild type. Both uev-3(ju587); rpm-1(lf) and uev-3(ju639); rpm-1(lf) double mutants show significant suppression of the rpm-1 phenotype, increasing SNB-1∷GFP puncta number to an average of 116.9 and 111.6 in the dorsal cord, respectively.

We also examined the touch neuron morphology using the muIs32 [Pmec-7-GFP] marker (Ch'ng et al. 2003). In wild-type animals, the ALM cell body lies laterally in the midbody region and sends a longitudinal axonal projection anterior into the pharyngeal region of the animal where a process branches into the nerve ring and forms synapses (Figure 2B). The PLM cell body resides in the tail and sends a projection anterior into the midbody of the animal, terminating posterior to the ALM cell body. PLM cells also extend a synaptic branch to the ventral cord to form synapses onto its partners. In rpm-1(lf) mutants, both ALM and PLM axons frequently overextend beyond their normal termination sites and loop posteriorly or into the ventral cord, described as “ALM hook” or “PLM hook” defects, respectively (Figure 2B). Additionally, the PLM synaptic branch is frequently missing. Although low levels of ALM and PLM defects are detected in uev-3(ju587) and uev-3(ju639) mutants, both mutations significantly suppressed rpm-1(lf) (Figure 2B). The degree of suppression of rpm-1(lf) by both alleles of uev-3 is comparable to those observed for the mutants in the DLK-1 MAPK cascade (Grill et al. 2007). uev-3(ju639) has a slightly stronger suppression effect on the mechanosensory neuron phenotypes, so we have designated ju639 as the cannonical mutation of the gene.

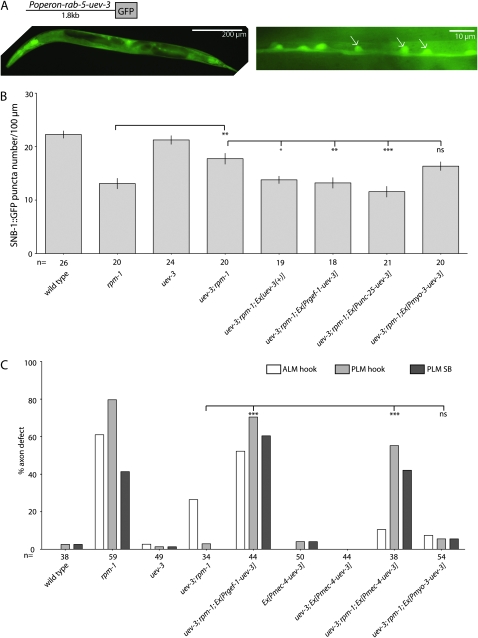

uev-3 acts cell autonomously in presynaptic neurons:

We determined the transcriptional expression pattern of the rab-5 and uev-3 operon using 1.8 kb of the 5′-upstream sequences of the operon to drive GFP expression. GFP is observed in all tissues and is noticeably present in ventral cord neurons (Figure 3A). We next addressed whether UEV-3 acts cell autonomously in neurons by expressing uev-3 cDNA driven by tissue-specific promoters in uev-3; rpm-1 mutants (Table S2 and Table S3). We examined functional rescue of the motor neuron synaptic phenotypes by quantitating SNB-1∷GFP puncta numbers (Figure 3B). Expression of uev-3 driven by a pan-neuronal promoter, or a motor neuron specific promoter rescues the suppression of rpm-1(lf) to similar degree comparable to that of transgenic-expressing uev-3 genomic DNA. The muscle promoter driven transgene did not show any effects on the suppression in uev-3; rpm-1 mutants. Similarly, we expressed uev-3 cDNA in touch neurons, and observed significant rescue of the suppression on the mechanosensory neuron phenotypes (Figure 3C). As in motor neurons, the muscle-driven promoter did not show any rescue activity in uev-3; rpm-1 mutants. The transgenes alone or in a uev-3 background did not cause any significant defects (Figure 3C, data not shown for [Pmyo-3-uev-3] and [Prgef-1-uev-3] transgenes alone). These results thus demonstrate that uev-3 is required cell autonomously in presynaptic neurons.

Figure 3.—

UEV-3 functions cell autonomously in presynaptic neurons. (A) The 1.8-kb promoter of the operon driven GFP (ixEx2 [Puev-3-GFP]) expression in many tissues (left), including the motor neurons of the ventral cord (white arrows, right). (B) Presynaptic expression of UEV-3 rescues the suppression of rpm-1 by uev-3 in the GABAergic motor neurons. Prgef-1, 3.5-kb pan-neural promoter; Punc-25, 1.2-kb GABAergic motor neuron promoter, and Pmyo-3, 1-kb body muscle promoter. Quantification of SNB-1∷GFP puncta in the dorsal nerve cord of young adults is shown as mean ± SEM; n as indicated. Statistics, ANOVA with Bonferroni correction: (*) P < 0.05, (**) P < 0.01, (***) P < 0.001, (ns) not significant. (C) Cell-autonomous rescue of the suppression of rpm-1 by uev-3 in touch neurons driven by the Pmec-4 promoter. n indicates animals scored. Statistics, Fischer Exact Test, comparing the PLM “hook” defects: (***) P < 0.001, (ns) not significant.

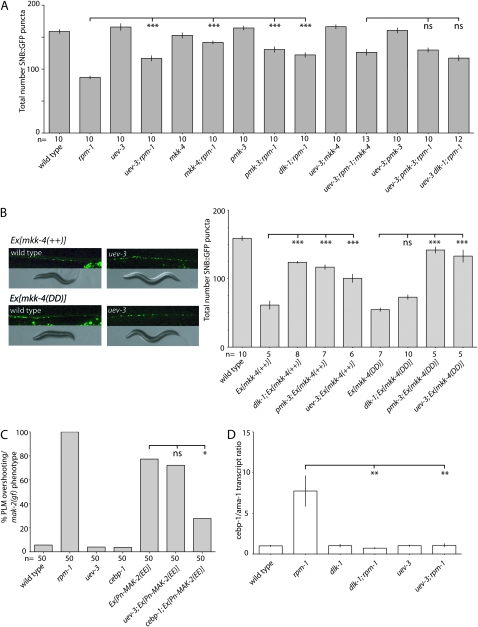

uev-3 acts downstream of mkk-4 and upstream of mak-2 in the DLK-1 MAPK cascade:

To learn how uev-3 functions in the DLK-1 MAPK cascade, we performed four lines of experiments. First, we made pairwise loss-of-function mutant combinations between uev-3 and the MAPK genes and measured the suppression of motor neuron puncta numbers in rpm-1(lf) (Figure 4A). For example, uev-3; rpm-1 have 116.9 SNB-1∷GFP puncta per dorsal cord, and pmk-3; rpm-1 have 130.7 puncta per dorsal cord. The triple mutants uev-3; pmk-3; rpm-1 show a mean 129.9 puncta number in the dorsal cord and do not suppress rpm-1 any stronger than either double mutants. This analysis is consistent with the interpretation that uev-3 acts in the same pathway with MAPK genes dlk-1, mkk-4, and pmk-3.

Figure 4.—

uev-3 acts in the DLK-1 MAPK cascade, downstream of mkk-4, and upstream of mak-2. (*) P < 0.05, (**) P < 0.01, (***) P < 0.001, (ns) not significant. (A) uev-3(lf) does not further enhance the suppression of rpm-1 in the motor neuron synapses by pmk-3 or mkk-4 or dlk-1. Numbers are mean ± SEM, n as indicated. Statistics, ANOVA with Bonferroni correction compared with rpm-1 single mutant. (B) uev-3 functions downstream of mkk-4 MAPKK. Transgenic animals overexpressing wild-type MKK-4 [mkk-4(++), juEx490] or expressing the constitutively active version of MKK-4 [mkk-4(DD), juEx669] display similarly abnormal synaptic patterns (juIs1), uncoordinated locomotion, and small body size (left). The phenotypes of both types of transgenes are suppressed by uev-3(ju587), and quantitation is shown on the right (mean ± SEM); ANOVA with Bonferroni correction: n as indicated. (C) uev-3 acts upstream of mak-2. Expression of a phosphomimetic MAK-2(EE) causes gain-of-function effects, which is suppressed by cebp-1, but not by uev-3. n as indicated. Statistics, Fischer exact test. (D) uev-3 acts in the dlk-1 pathway to regulate levels of cebp-1 transcripts, qRT–PCR levels of cebp-1 mRNAs normalized against ama-1. Statistics, Student's t-test: n = 3.

Second, to place uev-3 within the DLK-1 MAPK pathway, we took advantage of the observations that transgenic expression of either wild type mkk-4(++) or a phosphomimetic mkk-4(DD) in a wild-type background causes gain-of-function phenotypes (Nakata et al. 2005). The animals carrying these extra-chromosomal arrays display an uncoordinated movement, with disorganized synaptic puncta resembling those of rpm-1(lf) (Figure 4B). Loss-of-function in pmk-3, a gene downstream of mkk-4, can suppress both the synaptic and behavior defects associated with either mkk-4(++) or mkk-4(DD) transgene, whereas loss-of-function in dlk-1, which acts upstream of mkk-4, only suppresses the effects of mkk-4(++) (Nakata et al. 2005). We found that when either the mkk-4(++) or mkk-4(DD) transgene is in the uev-3(lf) background, the body size and movement phenotypes of the transgenic animals are abolished, and the average total synaptic GFP puncta are increased significantly (Figure 4B). Thus, uev-3 behaves genetically similar to pmk-3 and likely acts downstream of mkk-4.

Third, we have recently identified that the MAP kinase-activated protein kinase MAK-2 and the transcription factor CEBP-1 function downstream of PMK-3 (Yan et al. 2009). Transgenic overexpression of a phosphomimetic MAK-2, mak-2(EE), causes a gain-of-function defect resembling mkk-4(gf) transgenes, which are suppressed by loss-of-function in cebp-1 but not pmk-3 (Yan et al. 2009)(Figure 4C). We found that uev-3(lf) does not suppress the mak-2(EE) gain-of-function defects (Figure 4C), consistent with a conclusion that uev-3 likely acts upstream of mak-2.

Finally, we examined the levels of cebp-1 mRNA transcripts in uev-3 mutants. The DLK-1 MAP kinase cascade regulates cebp-1 by controlling the levels of cebp-1 mRNA (Yan et al. 2009). We performed quantitative RT–PCR on RNAs isolated from mixed-stage animals and compared the levels of cebp-1 transcripts to those of ama-1, the large subunit of RNA polymerase II (Sanford et al. 1983). In rpm-1 mutants, cebp-1 transcript levels are elevated compared to wild type because DLK-1 is not degraded, allowing high-level of MAP kinase signaling to promote the stability of cebp-1 mRNA (Figure 4D). In both rpm-1; dlk-1 and rpm-1; uev-3 mutant strains, the transcript levels of cebp-1 are comparable to wild-type levels. All together, these four lines of evidence show that uev-3 functions in the DLK-1 MAPK pathway, at the step between mkk-4 and mak-2.

The canonical uev-1 and ubc-13 do not suppress rpm-1:

Biochemical studies of canonical UEV proteins in yeast and mammalian cells, such as Mms2 and Uev1A, respectively, have established that the UEV domain functions as an obligatory subunit for an active Ubc, Ubc13 (Broomfield et al. 1998; Xiao et al. 1998; Deng et al. 2000). The Uev1A/Ubc13 E2 complex catalyzes Lys63 poly-ubiquitin chain formation (Hofmann and Pickart 1999; Vandemark et al. 2001). The ortholog of Mms2 or Uev1A in C. elegans is UEV-1, which can interact with UBC-13 (Gudgen et al. 2004). The UEV domain of the UEV-3 is very divergent from the canonical UEV (Figure 1C and Figure S1) and also shows limited degree of similarities to that of UEV-1 (14.7% identity and 30.6% similarity) (Figure 5A). Residues known to be important for Uev1 binding to either its cognate Ubc13 or ubiquitin do not seem to be conserved in UEV-3 (Moraes et al. 2001; Vandemark et al. 2001) (Figure 5A). In addition, UEV-3 has extended N-terminal sequences and short C-terminal tail (Figure 5B). The sequence comparisons raise the question whether UEV-3 may retain functions similar to those of UEV proteins in other organisms.

Figure 5.—

Functional comparison of UEV-1/UBC-13 and UEV-3. (A) Alignment of UEV-1 and UEV-3 UEV domains. Black boxes, identical residues and gray boxes, similar residues. Asterisk, conserved proline and tryptophan residues; caret, aspartic acid residue at the position where both UEV proteins lack the active cysteine. Solid line above residues in UEV-1 31-39 indicates the conserved region that would be important for interacting with Ubc13. Circled Ser, Thr and Ile residues have been shown to be on the interface of S. cerevisiae Mms2 with ubiquitin, which are not conserved in UEV-3. (B) Illustration of the uev-1 and ubc-13 genes and mutations. (C) Schematics of DNA constructs used in transgenic lines in panel D. (D) Quantification of genetic interactions between uev-1, ubc-13 and rpm-1 and transgenic UEV expression. Statistics, Fischer Exact Test; (***) P < 0.001; (ns) not significant.

We tested whether uev-1 and ubc-13 interacted with rpm-1. The uev-1 gene is a small gene, with its coding sequences less than 1 kb, and resides in an operon as the upstream gene (Figure 5B). A deletion allele, ok2610, removes 496 bp starting 142 bp in the promoter of the operon and ending 69 bp in the third exon of uev-1, and is likely a null mutation. The homozygous ok2610 animals are viable, develop normal touch neurons, and do not suppress rpm-1(lf) (Figure 5D). We also examined a deletion allele of ubc-13, tm3546, which breaks in the first exon and would lead to a premature stop at amino acid 88 (Figure 5B). We observed no genetic suppression of rpm-1(lf) by ubc-13(tm3546) (Figure 5D). Moreover, overexpression of uev-1 did not bypass the requirement of uev-3 (Figure 5D). We also made a chimeric gene in which we replaced the UEV domain and C terminus of UEV-3 with the UEV domain from UEV-1 (Figure 5C). Intriguingly, we found that transgenic expression of this UEV chimeric protein in neurons rescued the suppression of rpm-1(lf) in the uev-3; rpm-1 background to similar levels as does the expression of the full-length uev-3 (Figure 5D). With the caveat of overexpression, this result suggests that despite its divergency, the UEV domain of UEV-3 could have a function similar to that of the canonical UEV domain of UEV-1. We therefore wanted to test whether UEV-3 might require any other UBC. C. elegans has 22 annotated UBC genes. We analyzed available deletion or mutant alleles for several UBC genes, but observed no genetic interactions with rpm-1(lf) (Table S1). We also performed dsRNAi for 19 ubc genes in eri-1; rpm-1; muIs32 strain and did not observe detectable suppression of rpm-1(lf) (data not shown). We also tested protein interactions between UEV-3 and UBC genes using yeast two-hybrid assays and were not able to detect a positive interaction with UEV-3, out of 11 UBC genes and 2 UEV genes tested (data not shown). In summary, these studies suggest a scenario in which the UEV domain of UEV-3 might have a canonical function like UEV-1, but UEV-3 might likely have distinct partners for its function.

UEV-3 can bind PMK-3:

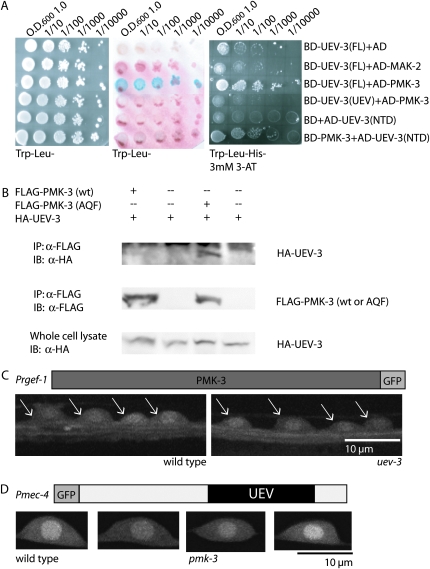

To better characterize the relationship between UEV-3 and the DLK-1 MAPK cascade, we asked whether UEV-3 could interact with the kinases by performing yeast two-hybrid assays between UEV-3 and all four kinases and CEBP-1. We detected interactions between UEV-3 and PMK-3, but not between UEV-3 and the other three kinases or CEBP-1 (Figure 6A, data not shown for dlk-1, mkk-4, cebp-1). We attempted to narrow down the interacting domains using bait expressing only the UEV domain or N-terminal domain of UEV-3, but were hindered by self-activation of the N-terminal expression construct and were not able to observe strong interactions between either domain alone and PMK-3 (Figure 6A). We further tested the binding interactions between UEV-3 and PMK-3 by co-immunoprecipitation studies in heterologous 293T cells. Although wild-type PMK-3 was not detectable in the immunocomplex with UEV-3, we observed co-immunoprecipitation between UEV-3 and a mutant PMK-3 in which the catalytic active site was mutated (Figure 6B). Such catalytic active site mutants of MAP kinases are often used to detect transient interactions between MAP kinases and their substrates or interacting partners (Han et al. 1997). Finally, we asked if this protein interaction might play roles in the localization or abundance of each protein. We generated transgenic animals expressing functional PMK-3∷GFP or UEV-3∷GFP in neurons. Both tagged proteins show ubiquitous expression in cytosol and nucleus (Figure 6, C and D). When each transgene was crossed into pmk-3 or uev-3 mutants, we did not observe major differences in the localization pattern or expression level of either transgene. Moreover, overexpression of pmk-3(+) in uev-3; rpm-1 mutants does not cause any detectable effects, nor does the overexpression of uev-3(+) in pmk-3; rpm-1 mutants (data not shown). Together with the genetic epistasis analyses, these data suggest that UEV-3 and PMK-3 are likely functional partners.

Figure 6.—

UEV-3 likely binds PMK-3. (A) UEV-3 interacts with PMK-3 but not with MAK-2 in yeast two-hybrid interaction assay, Trp–Leu plates (left), lacZ assay (middle), and Trp–Leu–His plates containing 3 mm 3-AT (right). UEV-3(FL), full-length UEV-3; UEV-3(UEV), UEV domain only; UEV-3(NTD), N-terminal domain, BD is binding domain and AD is activating domain. (B) HA-UEV-3 coimmunoprecipitated with FLAG-PMK-3(AQF) mutant but not with FLAG-PMK-3 wild type when coexpressed in 293T cells. (C) Functional PMK-3∷GFP (juEx675 [Prgef-1-PMK-3∷GFP]) in neurons is seen in cytoplasmic and nuclear compartments in wild type and is unaltered in uev-3(ju587) background. Arrows indicate neurons in the ventral cord. (D) Functional UEV-3∷GFP in mechanosensory neurons [juEx2118 Pmec-4-GFP∷UEV-3] localizes to cytoplasm and nucleus and is unaltered in pmk-3 mutant background.

DISCUSSION

The conserved DLK kinases have recently emerged as key regulators of axon and synapse development in the nervous systems of both vertebrates and invertebrates (Po et al. 2010). The mechanistic dissection of the DLK signal transduction cascade has only just begun. In this study, we identified and characterized a new member of the DLK-1 kinase pathway, UEV-3, a previously uncharacterized ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme/E2 variant. Like other MAPKs known to function in the DLK-1 pathway, loss-of-function of uev-3 on its own is grossly wild type, but shows specific suppression of rpm-1 in axon termination and synapse formation phenotypes. Our genetic epistasis studies reveal that uev-3 acts in the DLK-1 MAPK pathway, downstream of mkk-4 and upstream of mak-2. On the basis of our studies of UEV-3 protein and its tentative binding interactions with PMK-3, we propose that UEV-3 may act as a cofactor for PMK-3, for example, to modulate PMK-3 activation or to recognize substrates, resulting in fine tuning the DLK-1 signal transduction cascade.

A ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme variant could provide an additional means for pathway regulation and specificity by delineating the targets of the pathway. The UEV protein, Fts1, has been shown to act as a scaffold between protein kinase B (PKB/Akt) and 3-phosphoinositide-dependent kinase 1 (PDK1) (Remy and Michnick 2004). C. elegans has three closely related p38 MAP kinases that appear to be ubiquitously expressed (Berman et al. 2001). The function of UEV-3 may be to provide specificity for PMK-3 in the DLK-1 MAPK pathway during synaptogenesis and axon termination in neurons. Through the UEV-3 and PMK-3 interaction, substrates important for these processes may be selectively activated. Despite substantial efforts, we have not yet been able to directly test the contribution of UEV-3 in the activation of MAK-2, because of the lack of reagents to detect phosphorylated MAK-2 in vivo. However, the idea that UEV-3 could help PMK-3 to affect kinase activation, such as that of MAK-2, would be similar to those revealed by the role of Uev1/Ubc13 in TAK1 kinase activation in the IkK pathway (Deng et al. 2000; Wang et al. 2001).

Defining the roles of proteins linked to ubiquitination in the nervous system has been a major advance in the past decade (Tai and Schuman 2008). Comparing to what we have learned about the E3 ubiquitin ligases, relatively little is understood about the functional specificity and regulation of E2 enzymes. A classic example is the Drosophila Bendless (Thomas and Wyman 1984; Muralidhar and Thomas 1993), which is implicated in synapse function but acts distinctly different from the E3 ligase Highwire (Uthaman et al. 2008). Emerging expression studies suggest that UEV proteins are widely expressed in the developing nervous system (Watanabe et al. 2007). However, their functions are largely unknown. Our transgenic studies suggest that despite the sequence divergency of the UEV domain, UEV-3 might act in a manner similar to canonical UEV proteins. Nonetheless, with the limitations of available reagents, we were not able to identify a cognate E2 ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme for UEV-3.

An intriguing possibility remains that UEV-3 may be functioning on its own to help add additional regulation in the RPM-1 pathway. It is well established that the UEV protein Tsg101/Vps23 acts in the endocytic pathway to bind ubiquitinated proteins and remove them from the membrane (Katzmann et al. 2002). The endosomal sorting complex required for transport (ESCRT-1) contains Vps23 and two other Vps proteins necessary for recognizing and sorting cargo endocytosed at the plasma membrane. Vps23 binds ubiquitin conjugated to proteins at the plasma membrane and together with the ESCRT-II and -III complexes, target proteins are sorted through multivesicular bodies in the endosomal pathway. A recent study has shown that a splice variant of human Uev1 has an extended N-terminal domain, which can target the protein to endosomal-like organelles and confer regulation to EGF receptor signaling, possibly through protein degradation (Duex et al. 2010). UEV-3 is unusual in that it has a long N-terminal extension, which could have a regulatory role in UEV-3 function. This idea would be consistent with the observation that overexpression of the chimeric UEV-3-UEV-1 mimics the activity of full-length UEV-3, whereas overexpression of UEV-1 does not. The RPM-1 pathway has previously been connected to vesicular regulation through the biochemical interaction between RPM-1 and the RabGEF GLO-4 (Grill et al. 2007). A tempting possibility is that UEV-3 may provide crosstalk between the GLO-4 and DLK-1 pathways by binding ubiquitinated proteins through its UEV domain and acting in the endosomal pathway. Potential future directions would be to identify UEV-3-interacting proteins to aid in further elucidation of UEV-3′s mechanism in axon termination and synapse formation.

Acknowledgments

We thank H. Taru for advice on Yeast two-hybrid, L. Boyd for C. elegans Ubc clones, and our lab members for input. We are grateful for the deletion alleles generated by Shohei Mitani and the National Bioresearch Project (Tokyo Women's Medical University School of Medicine, Tokyo, Japan) and C. elegans knockout consortium. Some of the strains were obtained from Caenorhabditis Genetics Center, which is supported by grants from National Institutes of Health (NIH)–National Center for Research Resources. This work was supported by Japan's Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (19500306) to K.N., NIH R01-035546 to Y.J. D.Y. is a research associate and Y.J. an investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

Supporting information is available online at http://www.genetics.org/cgi/content/full/genetics.110.117341/DC1.

References

- Babst, M., G. Odorizzi, E. J. Estepa and S. D. Emr, 2000. Mammalian tumor susceptibility gene 101 (TSG101) and the yeast homologue, Vps23p, both function in late endosomal trafficking. Traffic 1 248–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berman, K., J. McKay, L. Avery and M. Cobb, 2001. Isolation and characterization of pmk-(1–3): three p38 homologs in Caenorhabditis elegans. Mol. Cell. Biol. Res. Commun. 4 337–344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloom, A. J., B. R. Miller, J. R. Sanes and A. DiAntonio, 2007. The requirement for Phr1 in CNS axon tract formation reveals the corticostriatal boundary as a choice point for cortical axons. Genes Dev. 21 2593–2606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenner, S., 1974. The genetics of Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics 77 71–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broomfield, S., B. L. Chow and W. Xiao, 1998. MMS2, encoding a ubiquitin-conjugating-enzyme-like protein, is a member of the yeast error-free postreplication repair pathway. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95 5678–5683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ch'ng, Q., L. Williams, Y. S. Lie, M. Sym, J. Whangbo et al., 2003. Identification of genes that regulate a left-right asymmetric neuronal migration in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics 164 1355–1367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins, C. A., Y. P. Wairkar, S. L. Johnson and A. Diantonio, 2006. Highwire restrains synaptic growth by attenuating a MAP kinase signal. Neuron 51 57–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis, M. W., M. Hammarlund, T. Harrach, P. Hullett, S. Olsen et al., 2005. Rapid single nucleotide polymorphism mapping in C. elegans. BMC Genomics 6 118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng, L., C. Wang, E. Spencer, L. Yang, A. Braun et al., 2000. Activation of the IkappaB kinase complex by TRAF6 requires a dimeric ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme complex and a unique polyubiquitin chain. Cell 103 351–361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiAntonio, A., A. P. Haghighi, S. L. Portman, J. D. Lee, A. M. Amaranto et al., 2001. Ubiquitination-dependent mechanisms regulate synaptic growth and function. Nature 412 449–452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Souza, J., M. Hendricks, S. Le Guyader, S. Subburaju, B. Grunewald et al., 2005. Formation of the retinotectal projection requires Esrom, an ortholog of PAM (protein associated with Myc). Development 132 247–256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duex, J. E., M. R. Mullins and A. Sorkin, 2010. Recruitment of Uev1B to Hrs-containing endosomes and its effect on endosomal trafficking. Exp. Cell Res. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Fields, S., and R. Sternglanz, 1994. The two-hybrid system: an assay for protein-protein interactions. Trends Genet. 10 286–292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grill, B., W. V. Bienvenut, H. M. Brown, B. D. Ackley, M. Quadroni et al., 2007. C. elegans RPM-1 Regulates Axon Termination and Synaptogenesis through the Rab GEF GLO-4 and the Rab GTPase GLO-1. Neuron 55 587–601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gudgen, M., A. Chandrasekaran, T. Frazier and L. Boyd, 2004. Interactions within the ubiquitin pathway of Caenorhabditis elegans. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 325 479–486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hallam, S. J., and Y. Jin, 1998. lin-14 regulates the timing of synaptic remodelling in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature 395 78–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han, J., Y. Jiang, Z. Li, V. V. Kravchenko and R. J. Ulevitch, 1997. Activation of the transcription factor MEF2C by the MAP kinase p38 in inflammation. Nature 386 296–299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann, R. M., and C. M. Pickart, 1999. Noncanonical MMS2-encoded ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme functions in assembly of novel polyubiquitin chains for DNA repair. Cell 96 645–653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurley, J. H., S. Lee and G. Prag, 2006. Ubiquitin-binding domains. Biochem. J. 399 361–372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin, Y., and C. C. Garner, 2008. Molecular mechanisms of presynaptic differentiation. Annu. Rev. Cell. Dev. Biol. 24 237–262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones, D., E. Crowe, T. A. Stevens and E. P. Candido, 2002. Functional and phylogenetic analysis of the ubiquitylation system in Caenorhabditis elegans: ubiquitin-conjugating enzymes, ubiquitin-activating enzymes, and ubiquitin-like proteins. Genome Biol. 3 research0002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Katzmann, D. J., G. Odorizzi and S. D. Emr, 2002. Receptor downregulation and multivesicular-body sorting. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 3 893–905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kipreos, E. T., 2005. Ubiquitin-mediated pathways in C. elegans (December 01, 2005), WormBook, ed. The C. elegans Research Community, WormBook, doi/10.1895/wormbook.1.36.1, http://www.wormbook.org. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Lewcock, J. W., N. Genoud, K. Lettieri and S. L. Pfaff, 2007. The ubiquitin ligase Phr1 regulates axon outgrowth through modulation of microtubule dynamics. Neuron 56 604–620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, H., G. Kulkarni and W. G. Wadsworth, 2008. RPM-1, a Caenorhabditis elegans protein that functions in presynaptic differentiation, negatively regulates axon outgrowth by controlling SAX-3/robo and UNC-5/UNC5 activity. J. Neurosci. 28 3595–3603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao, E. H., W. Hung, B. Abrams and M. Zhen, 2004. An SCF-like ubiquitin ligase complex that controls presynaptic differentiation. Nature 430 345–350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mello, C. C., J. M. Kramer, D. Stinchcomb and V. Ambros, 1991. Efficient gene transfer in C. elegans: extrachromosomal maintenance and integration of transforming sequences. EMBO J. 10 3959–3970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moraes, T. F., R. A. Edwards, S. McKenna, L. Pastushok, W. Xiao et al., 2001. Crystal structure of the human ubiquitin conjugating enzyme complex, hMms2-hUbc13. Nat. Struct. Biol. 8 669–673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muralidhar, M. G., and J. B. Thomas, 1993. The Drosophila bendless gene encodes a neural protein related to ubiquitin-conjugating enzymes. Neuron 11 253–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakata, K., B. Abrams, B. Grill, A. Goncharov, X. Huang et al., 2005. Regulation of a DLK-1 and p38 MAP kinase pathway by the ubiquitin ligase RPM-1 is required for presynaptic development. Cell 120 407–420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pickart, C. M., and M. J. Eddins, 2004. Ubiquitin: structures, functions, mechanisms. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1695 55–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Po, M. D., C. Hwang and M. Zhen, 2010. PHRs: bridging axon guidance, outgrowth and synapse development. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 20 100–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raman, M., W. Chen and M. H. Cobb, 2007. Differential regulation and properties of MAPKs. Oncogene 26 3100–3112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Remy, I., and S. W. Michnick, 2004. Regulation of apoptosis by the Ft1 protein, a new modulator of protein kinase B/Akt. Mol. Cell. Biol. 24 1493–1504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sancho, E., M. R. Vila, L. Sanchez-Pulido, J. J. Lozano, R. Paciucci et al., 1998. Role of UEV-1, an inactive variant of the E2 ubiquitin-conjugating enzymes, in in vitro differentiation and cell cycle behavior of HT-29–M6 intestinal mucosecretory cells. Mol. Cell. Biol. 18 576–589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanford, T., M. Golomb and D. L. Riddle, 1983. RNA polymerase II from wild type and alpha-amanitin-resistant strains of Caenorhabditis elegans. J. Biol. Chem. 258 12804–12809. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaefer, A. M., G. D. Hadwiger and M. L. Nonet, 2000. rpm-1, a conserved neuronal gene that regulates targeting and synaptogenesis in C. elegans. Neuron 26 345–356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skaug, B., X. Jiang and Z. J. Chen, 2009. The role of ubiquitin in NF-kappaB regulatory pathways. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 78 769–796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tai, H. C., and E. M. Schuman, 2008. Ubiquitin, the proteasome and protein degradation in neuronal function and dysfunction. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 9 826–838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, J. B., and R. J. Wyman, 1984. Mutations altering synaptic connectivity between identified neurons in Drosophila. J. Neurosci. 4 530–538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uthaman, S. B., T. A. Godenschwege and R. K. Murphey, 2008. A mechanism distinct from highwire for the Drosophila ubiquitin conjugase bendless in synaptic growth and maturation. J. Neurosci. 28 8615–8623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VanDemark, A. P., R. M. Hofmann, C. Tsui, C. M. Pickart and C. Wolberger, 2001. Molecular insights into polyubiquitin chain assembly: crystal structure of the Mms2/Ubc13 heterodimer. Cell 105 711–720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wan, H. I., A. DiAntonio, R. D. Fetter, K. Bergstrom, R. Strauss et al., 2000. Highwire regulates synaptic growth in Drosophila. Neuron 26 313–329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C., L. Deng, M. Hong, G. R. Akkaraju, J. Inoue et al., 2001. TAK1 is a ubiquitin-dependent kinase of MKK and IKK. Nature 412 346–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe, M., H. Mizusawa and H. Takahashi, 2007. Developmental regulation of rat Ubc13 and Uev1B genes in the nervous system. Gene Expr. Patterns 7 614–619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitmarsh, A. J., 2006. The JIP family of MAPK scaffold proteins. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 34 828–832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu, C., R. W. Daniels and A. DiAntonio, 2007. DFsn collaborates with Highwire to down-regulate the Wallenda/DLK kinase and restrain synaptic terminal growth. Neural Dev. 2 16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, W., S. L. Lin, S. Broomfield, B. L. Chow and Y. F. Wei, 1998. The products of the yeast MMS2 and two human homologs (hMMS2 and CROC-1) define a structurally and functionally conserved Ubc-like protein family. Nucleic Acids Res. 26 3908–3914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan, D., Z. Wu, A. D. Chisholm and Y. Jin, 2009. The DLK-1 kinase promotes mRNA stability and local translation in C. elegans synapses and axon regeneration. Cell 138 1005–1018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhen, M., X. Huang, B. Bamber and Y. Jin, 2000. Regulation of presynaptic terminal organization by C. elegans RPM-1, a putative guanine nucleotide exchanger with a RING-H2 finger domain. Neuron 26 331–343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]