SUMMARY

N-linked glycosylation is the most frequent modification of secreted and membrane-bound proteins in eukaryotic cells, disruption of which is the basis of the Congenital Disorders of Glycosylation (CDG). We describe a new type of CDG caused by mutations in the steroid 5α-reductase type 3 (SRD5A3) gene. Patients have mental retardation, ophthalmologic and cerebellar defects. We found that SRD5A3 is necessary for the reduction of the alpha-isoprene unit of polyprenols to form dolichols, required for synthesis of dolichol-linked monosaccharides and the oligosaccharide precursor used for N-glycosylation. The presence of residual dolichol in cells depleted for this enzyme suggests the existence of an unexpected alternative pathway for dolichol de novo biosynthesis. Our results thus suggest that SRD5A3 is likely to be the long-sought polyprenol reductase and reveal the genetic basis of one of the earliest steps in protein N-linked glycosylation.

Keywords: N-glycosylation, dolichol, polyprenol, SRD5A3

INTRODUCTION

N-glycosylation occurs on certain asparagine residues present on nascent polypeptides in all eukaryotic cells. The glycan structures resulting from this process show an incredible variability depending on the protein, cell type, and species. This essential posttranslational modification occurs on most secreted and plasma membrane proteins, and is involved in protein folding and trafficking with implications for cell-cell and cell-matrix interactions and intra-cellular signaling (Freeze, 2006; Helenius and Aebi, 2001). The process of N-linked protein glycosylation is localized in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and the Golgi compartment. Three separate phases can be distinguished: first, the assembly of an oligosaccharide precursor, a block of 14 monosaccharides (Glc3Man9GlcNAc2), on the lipid carrier dolichol-phosphate (Dol-P) in the ER membrane. Second, this glycan is transferred co-translationally or post-translationally to dedicated asparagine residues of nascent glycoproteins (Ruiz-Canada et al., 2009). In this reaction, oligosaccharyltransferase (OST) recognizes the acceptor sequence NX[S/T] (where × can be any amino acid except proline) on nascent polypeptides and catalyzes the transfer of the glycan precursor en bloc from its lipid carrier to the protein (Chavan and Lennarz, 2006). Third, the N-linked glycan is further modified by a series of trimming and elongation reactions beginning in the ER and ending in the late Golgi compartment.

The early steps of this pathway are present not only in eukaryotic cells, but also in archae and bacteria, all relying on a lipid to build an oligosaccharide precursor (Jones et al., 2009). This carrier lipid, a polyisoprenoid, is assembled from a variable number of isoprene units, linked head to tail. The length of the carrier polyisoprenoid varies across evolution: bacteria posses a single prenol, undecaprenol (usually composed of 11 isoprene units), but in eukaryotic cells these lipids typically occur as mixtures of different lengths, depending upon the species. In mammalian cells, dolichols are predominantly 18–21 isoprene units in length.

A requirement in eukaryotic organisms is the reduction of the precursor polyprenol to dolichol on the terminal isoprene unit (alpha) (Swiezewska and Danikiewicz, 2005), followed by phosphorylation to generate Dol-P. The identification of Dol-P as glycosyl carrier lipids in glycosylation was described 40 years ago (Behrens and Leloir, 1970) but the role of the free lipid, broadly distributed in mammalian cells (Rip et al., 1985), and some of its biosynthetic steps remain elusive. Using prenol labeling studies, a pathway for dolichol biosynthesis was proposed (Sagami et al., 1993), however, several enzymes were still missing, including a polyprenol reductase. In this article the term “polyprenol” will be restricted to alpha-unsaturated compounds, despite its more general meaning, to distinguish them from dolichol, as it is commonly done in the literature. Several glycosylation-defective cell lines, generated in vitro, showed accumulation of polyprenol instead of dolichol (Acosta-Serrano et al., 2004; Rosenwald et al., 1993) and suggested that polyprenol reduction was the rate-limiting step in dolichol synthesis, with major consequences on N-glycosylation.

In humans, a disruption of N-glycosylation results in congenital disorders of glycosylation (CDG), a growing class of hereditary disorders (Freeze, 2006; Grunewald and Matthijs, 2000; Haeuptle and Hennet, 2009; Jaeken and Matthijs, 2007). Defects in the maturation and transfer of the glycan precursor, located in the ER, have been grouped in the past as CDG type I, and disorders affecting the subsequent N-glycan processing steps grouped as CDG type II. A recently proposed alternate nomenclature uses only the gene name together with a CDG suffix (Jaeken et al., 2009). These diseases show wide symptomatology and severity. The main features are psychomotor retardation, cerebellar ataxia, seizures, retinopathy, liver fibrosis, coagulopathies, failure to thrive, dysmorphic features including abnormal fat distribution and ophthalmological anomalies (Eklund and Freeze, 2006). Even though a multi-system phenotype is often observed, several cases have been reported with primary neurological involvement including cerebellar ataxia (Vermeer et al., 2007), suggesting that cerebellar disease maybe a sensitive measure of defective N-glycosylation.

In this study, we identify SRD5A3 orthologs as necessary for and promoting the reduction of polyprenol to dolichol in human, mouse and yeast and describe a new syndrome of CDG type I in 7 families caused by a defect in this newly identified polyprenol reductase.

RESULTS

Loss of function mutations of the SRD5A3 gene cause a multisystemic syndrome with eye malformations, cerebellar vermis hypoplasia, and psychomotor delay

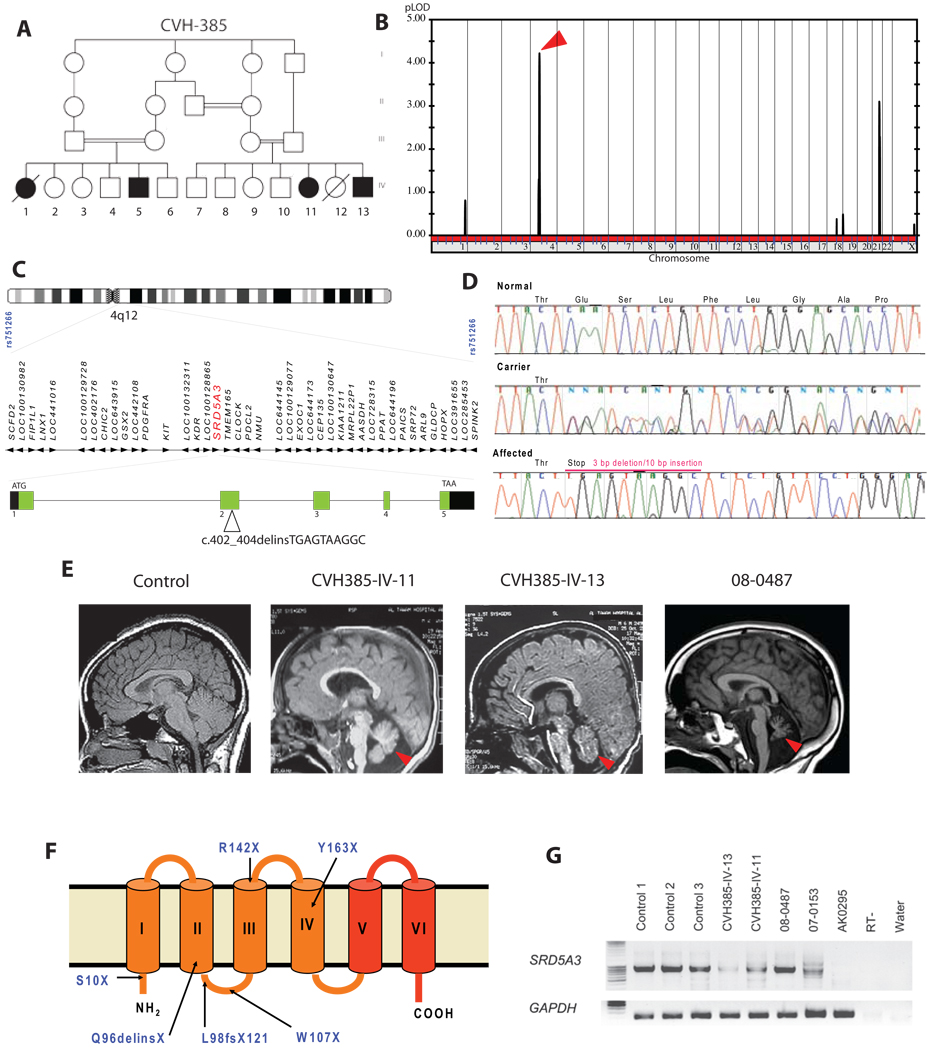

We identified a large consanguineous Emirati family of Baluchi (Southern Iran) origin (CVH-385, Figure 1A) (Al-Gazali et al., 2008). All affected children displayed ocular colobomas, ichthyosis, heart defect, developmental delay and brain malformations including cerebellar vermis hypoplasia. We performed a genome-wide linkage analysis and mapped the disease locus on chromosome 4q12 with a multipoint LOD score of 4.2 (Figure 1B). This mapping defined an interval of 53.8–57.4MB (between the markers rs751266 and rs899631) encompassing 42 genes (based on NCBI genome browser, build 36 version 3) (Figure 1C), which were screened using a systematic mutational analysis of candidates with bidirectional sequencing. Analysis of the steroid 5 alpha-reductase 3 (SRD5A3) gene, coding for a 318 amino acid enzyme of unknown function, identified a molecular rearrangement with a homozygous 3 bp deletion and a 10 bp insertion resulting in a predicted stop codon at amino acid 96 (Figure 1D). To exclude the possibility that this change represented a common polymorphism, we tested 96 DNAs (192 chromosomes) from geographically matched controls but identified no carriers. Although CHIME syndrome (Colobomas of the eye, Heart defects, Ichthyosiform dermatosis, Mental retardation, and Ear defects or Epilepsy) was the closest related disease without a known molecular cause (Sidbury and Paller, 2001), four families with this syndrome tested negative for SRD5A3 mutations. However, another family of Baluchi origin (MR3) also living in the Emirates with a comparable phenotype (Table1), displayed the same molecular rearrangement in SRD5A3 (despite denying known relationship with CVH-385 family) suggesting the existence of a common founder mutation. Due to the phenotypic similarity with CDG, we tested the N-glycosylation status of transferrin using mass spectrometry (MS) (O’Brien et al., 2007), a reliable screening test for Type I CDG patients. Transferrin is a serum protein with two N-glycosylation sites, fully occupied in control individuals. CVH-385 and MR3 patients showed a very clear defect with respectively about 45% and 25% of mono-glycosylated transferrin suggesting that the SRD5A3 mutation leads to a type I CDG (Figure 2A and Figure S2A). We also found a defect in extra-cellular secretion of N-glycosylated DNAse I in index patients’ fibroblasts (Figure S2B), a sensitive measure of defective N-glycosylation (Nishikawa and Mizuno, 2001; Vleugels et al., 2009)

Figure 1. Identification of mutations in the SRD5A3 gene in patients with multisystemic syndrome including cerebellar hypoplasia.

(A) Pedigree of family CVH-385 showing several levels of consanguinity with cousin marriages. The two branches each produced two affected offspring represented by filled symbols in generation IV.

(B) Whole-genome analysis of linkage results with chromosomal position (x-axis) and multipoint LOD score (y-axis) showing a peak LOD score of 4.2 on chromosome 4 (arrowhead).

(C) Expanded view of the candidate interval on chromosome 4q12, containing 42 candidate genes including SRD5A3 (red), spanning 25.5 kb of genomic DNA with 5 exons. A mutation in exon 2 was identified in family CVH-385.

(D) DNA sequence of exon 2 of SRD5A3 from a control individual, an obligate carrier, and an affected family member from CVH-385. The mutation consists of a 3 bp deletion associated with a 10 bp insertion, resulting in a frame shift and premature termination at amino-acid 96 of 318, within the second of six transmembrane domains.

(E) Brain MRI midline sagittal view showing cerebellar vermis hypoplasia (red arrowhead) in SRD5A3 mutated patients.

(F) Topology model of SRD5A3 with mutations indicated and 6 transmembrane domains. Mutations were scattered throughout the ORF, all leading to predicted protein termination before the steroid reductase domain (in red).

(G) Amplification of the SRD5A3 transcript by RT-PCR using RNA extracted from controls and patient fibroblasts. The expression level of the gene is lower in almost all patients CVH-385-IV-13, CVH-385-IV-11, 07–0153 compared to control, suggesting nonsense mediated mRNA decay. No expression was detected in patient AK0295, due to a homozygous genomic rearrangement. RT-, no reverse transcriptase; water, no cDNA. See also Figure S1.

Table 1.

Clinical phenotype associated withSRD5A3 mutations

| CVH-385 | MR3 | 08–0487/86 | 08–0904 | 07–0153 | 07–0419 | AK0295 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ethnic background | Baluchi | Baluchi | Polish | Turkish | Polish | Turkish | Turkish |

| Consanguinity | + | + | + | + | − | + | + |

| Muscle hypotonia/motor retardation | +/− | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Mental retardation | + | + | + | + | + | +/− | + |

| Cerebellar atrophy/vermis malformations | + | NA | + | + | + | − | + |

| Spasticity | +/− | +/− | + | − | − | − | − |

| Movement disorder/dystonia | − | +/− | + | − | − | − | +/− |

| Visual loss | +/− | + | + | + | + | +/− | + |

| Hypoplasia or coloboma/iris/retina/chorioid/optic disc |

+ | + | + | + | + | − | + |

| Nystagmus | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Optic atrophy | + | + | + | + | + | − | − |

| Other eye malformation (microphthalmia /glaucoma/cataract) |

microphthalmia | − | + | cataract | − | glaucoma | microphthalmia cataract |

| Cardiac malformation/cardiac hypertrophy | + | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| Ichtiosis/erythroderma | + | − | − | + | + | − | + |

| Dry skin/atopic dermatitis | + | + | +/ − | − | + | − | + |

| Inverted nipples | − | − | − | + | − | + | − |

| Joint contractures | +/− | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| Swallowing problems | + | + | − | − | − | − | + |

| Failure to thrive | + | − | − | − | − | − | + |

| Microcitic anemia | + | + | + | + | − | − | + |

| Elevated liver enzymes | + | NA | + | + | + | + | + |

| Abnormal coagulation studies | NA | NA | + | + | + | + | + |

| Decreased antithrombine 3/protein C and S levels | NA | NA | + | + | + | + | + |

| Mutation cDNA | c.402_404 delinsTGAGTAAGGC | c.292_293del | c.320 G>A | het c.424 C>T het c.524 C>A |

c.29 C>A | Genomic rearrangement |

|

| Mutation at protein level | p.Gln96delinsX | p.Leu98ValfsX121 | p.Trp107X | p.Arg142X p.Tyr163X |

p.Ser10X | Absent | |

NA: data not available

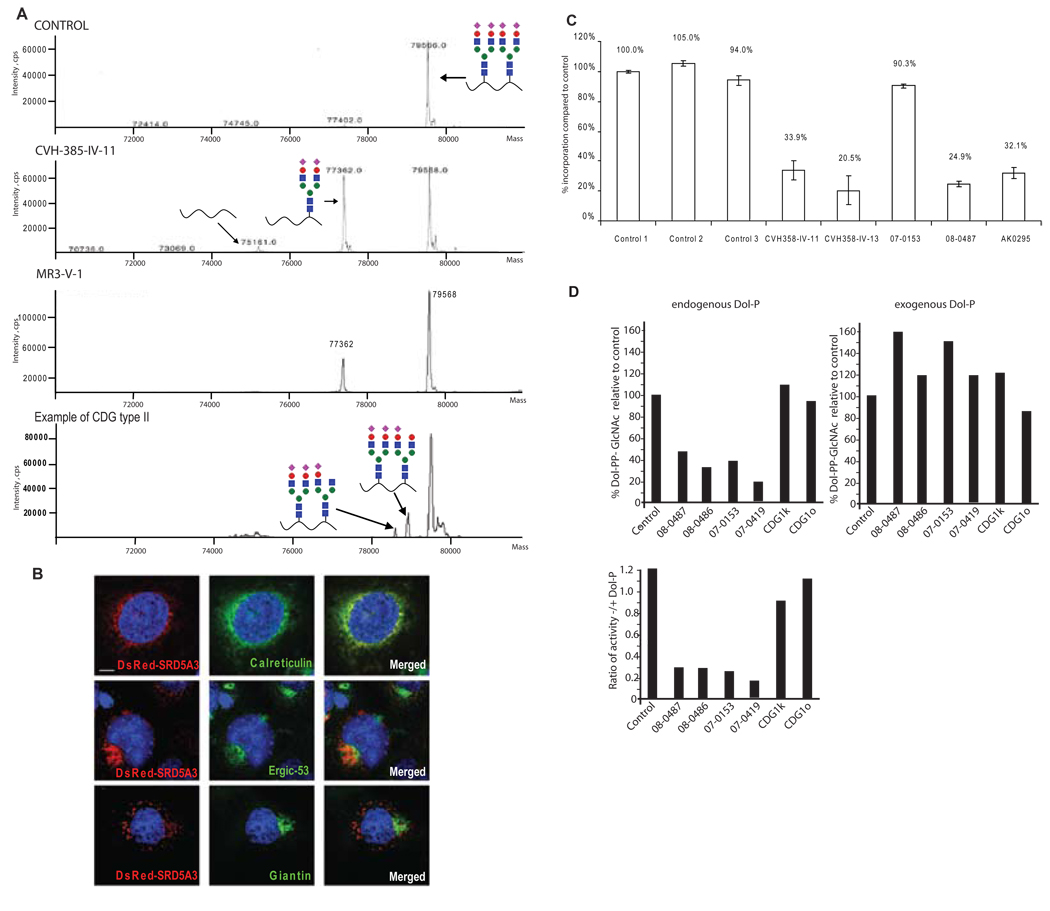

Figure 2. SRD5A3 mutated patients have a congenital disorder of glycosylation type I caused by a defect in lipid-linked oligosaccharide (LLO) synthesis, rescued in vitro with exogenous dolichol phosphate.

(A) Mass spectra of transferrin, normally N-glycosylated on two sites, Asn-432 and Asn-630 (control). Transferrin containing a single N-glycan in SRD5A3 patient samples was increased, indicating a CDG type I disorder. An example of transferrin profile from CDG type II patient, with two glycan chains but abnormal structure (depicted by lack of certain sugar moieties) for comparison.

(B) Intra cellular localization of SRD5A3 containing a N-terminus DsRed tag (center panel) in COS7 cells costained with antibody against ER specific marker, calreticulin, ERGIC specific marker ERGIC53 and Golgi specific marker Giantin. DsRed-SRD5A3 colocalized with most of the ER whereas Giantin staining did not colocalize. Scale bar = 10µm.

(C) Incorporation of [3H]-mannose into LLO after labeling of human fibroblasts. The results indicate severely reduced levels of LLO in 4 of 5 patient samples.

(D) Rescue of LLO precursor levels with exogenous Dol-P. GlcNAc transferase activity in fibroblasts was measured. Microsomal fractions from fibroblasts were incubated with radioactive GlcNAc and then Dol-PP-GlcNAc1/2 formation was analyzed by TLC. Extracts from patients’ fibroblasts produced a reduced amount of Dol-PP-GlcNAc1/2. However the addition of exogenous Dol-P rescued this defect.

See also Figure S2.

Consequently, we screened 38 patients with CDG type I–x (CDG type I negative for known gene mutations) and we identified 5 other independent homozygous or compound heterozygous mutations and one genomic rearrangement (Figure 1F, Table1 and Figure S1). Among the mutations identified, were a 2 base-pair deletion and 4 single base substitutions resulting in stop codons. Additionally, patient AK0295 carried a homozygous truncation of the gene encompassing within exon 5, in the 3’ part of SRD5A3 ORF. Further expression analysis in patients’ fibroblasts showed partial nonsense mediated mRNA decay of SRD5A3 transcript in some patients (Figure 1G). Based on the phenotype of eleven children from seven families, the most striking features observed were the presence of congenital eye malformations with variable degree of visual loss, nystagmus, muscle hypotonia, motor delay, mental retardation and facial dysmorphism. Microcytic anemia, elevated levels of liver enzyme activities, coagulation abnormalities and decreased antithrombin III levels were detected in nine evaluated cases. Most children presented with ocular coloboma or hypoplasia of the optic disc (unique features in the CDGs) (Morava et al., 2009), with striking cerebellar atrophy or vermis malformation. Ichthyosiform erythroderma or dry skin and congenital heart malformations were sporadically present. Midline malformations and endocrine anomalies were only present in the index patients (Al-Gazali et al., 2008) (Table1). The relative uniformity in the biochemical and clinical phenotype associated with frequent early truncating mutations suggests loss-of-function of SRD5A3 as the genetic mechanism.

Patients with mutation in SRD5A3 show an early defect in lipid-linked oligosaccharide synthesis

The absence of whole glycan chains on proteins indicated that the metabolic block occurred early in the N-glycosylation pathway, altering synthesis or transfer of the glycan part of lipid linked oligosaccharide (LLO), to recipient proteins. Epitope tagged SRD5A3 localized predominantly to the ER (Figure 2B), where LLO synthesis occurrs (Aebi and Hennet, 2001).

An abnormal composition of the glycan precursor impairs its transfer to acceptor proteins. Accordingly we investigated the size of the LLO glycans using HPLC after [2- 3H]-mannose metabolic labeling with fibroblasts from index patients CVH-385-IV-11 and CVH-385-IV-13. Since no major structural abnormalities in LLO were detected (Figure S2E), we also determined the amount of radiolabeled LLO. We detected a severe reduction in the amount of newly synthesized LLO in 4 of the 5 patients tested compared to 3 control cell lines (Figure 2C), suggesting that the N-glycosylation block occurs prior the glycan transfer step.

The reduced levels of LLO could be explained by a limited availability of Dol-P. To test this hypothesis, we used an in vitro assay to asses the production of Dol-PP-GlcNAc1 and Dol-PP-GlcNAc2, the first two reactions of LLO synthesis. Using fibroblast homogenates as a source of enzyme and UDP-[14C]GlcNAc as glycosyl donor, all SRD5A3 deficient patient samples showed a reduced synthesis of Dol-PP-GlcNAc1/2 without addition of exogenous Dol-P, compared to controls (Figure 2D). However, when exogenous Dol-P was added to the incubation mixture, formation of Dol-PP-GlcNAc1/2 was increased to levels comparable with or even higher than controls. Fibroblasts from patients with other known CDG-I defects (CDG-Ik or CDG-Io) behaved comparable to controls, showing no evidence of Dol-P mediated rescue (Figure 2D). Elongation of Dol-PP-GlcNAc2 to Dol-PP-GlcNAc2-Man5 was unremarkable. Similarly, OST activity was normal (data not shown). Altogether, the rescue of the enzymatic GlcNAc transferases deficiencies by exogenous Dol-P indicates that the amount of Dol-P is limiting in the patients’ fibroblasts and suggests a defect in Dol or Dol-P biosynthesis.

SRD5A3 is the Human ortholog of yeast DFG10/YIL049W gene

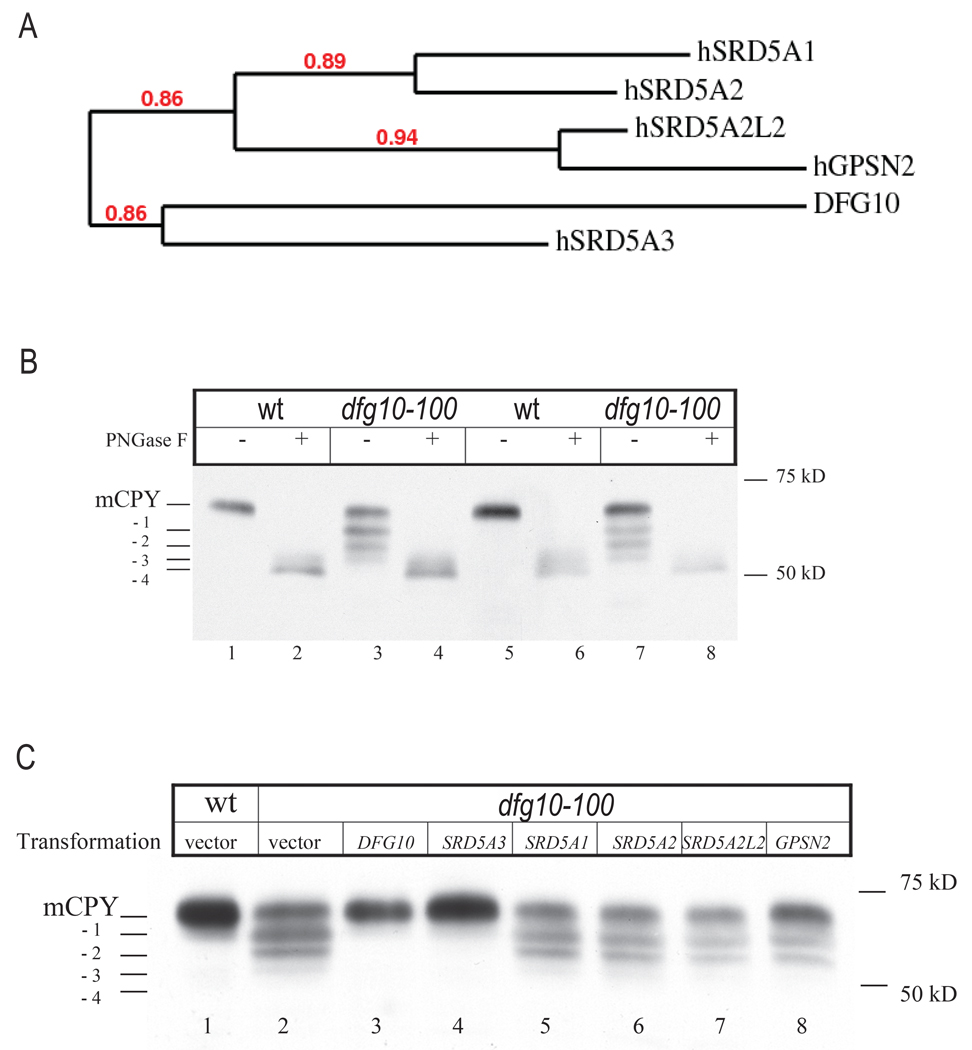

A yeast mutant for the DFG10 gene, called dfg10–100, was previously isolated by a genetic screen for mutant strains defective for filamentous growth (dfg), using insertional mutagenesis (Mosch and Fink, 1997). The product of this gene shows 25% amino acid identity and 43% similarity with the human SRD5A3 protein (Blastp, NCBI). To determine whether DFG10 is the yeast ortholog of SRD5A3 (Figure 3A), we first asked whether the dfg10–100 mutant displays a lack of N-glycan modifications. Carboxypeptidase Y (CPY) is a secreted enzyme with a mature form that contains four N-glycan sites, all of which are occupied under optimal growth conditions (Hasilik and Tanner, 1978), and all of which can be removed with PNGase F treatment. In contrast with wt strain (L5366), the dfg10–100 mutants (diploid and homozygous at the DFG10 locus) produced hypoglycosylated CPY, with the detection of tri-, di- and mono-glycosylated CPY (Figure 3B). Because the dfg10–100 mutant is a result of a transposon insertion into the DFG10 promoter, it was possible that still some protein was expressed, thus accounting for the non lethal phenotype. This possibility was excluded by engineering a deletion of the whole DFG10 ORF, which produced an identical growth delay and CPY phenotype (Figure S3). The identification of a similar biochemical defect in yeast and human suggests a conserved function for SRD5A3 across evolution.

Figure 3. N-glycosylation phenotype of dfg10–100 yeast mutant and rescue with human SRD5A3.

(A) Phylogenic tree representation of the yeast protein DFG10 and human proteins presenting a steroid 5-alpha reductase domain, with branch support value indicated in red.

(B) N-glycosylation status of the yeast protein CPY in yeast wt and dfg10–100 mutant strain, mutated by transposon insertion. Two colonies from each strain were tested. CPY is post-translationally modified by the addition of four glycan chains. In the dfg10–100 mutants, a protein lacking one, two or tree glycan chains is detected. Protein extracts were treated with PNGaseF to remove the N-glycans.

(C) Glycosylation status of CPY in dfg10–100 mutant transformed with each steroid 5-alpha reductase domain containing gene from human. Only SRD5A3 showed rescue effect. Positions of mature CPY (mCPY) and the different glycoforms (−1,−2,−3,−4) are indicated. Vector indicates empty vector control.

See also Figure S3.

In human, five partially homologous genes compose the steroid 5-alpha reductase family, including the well characterized SRD5A1, SRD5A2 involved in testosterone reduction (Russell and Wilson, 1994), encoding for proteins targeted in treatments against prostate cancer and male pattern hair loss (Aggarwal et al., 2009), and also SRD5A2L2, GPSN2, SRD5A3 that are less characterized. Bioinformatics comparison showed that the DFG10 sequence shares most identity with SRD5A3 (BLASTP, E value = 2e-13) whereas SRD5A1, SRD5A2, SRD5A2L2 and GPSN2 show E values of, respectively 6e-04, 3e-04, 3e-04 and 5e-05 (Figure 3A). To test for functional conservations we expressed each mammalian ORF under the control of a strong constitutive yeast promoter (Alber and Kawasaki, 1982) in the dfg10–100 mutant. The mutant transformed with yeast DFG10 showed a full correction of the CPY under-glycosylation. Furthermore SRD5A3 was the only homologue able to rescue the phenotype (Figure 3C). This experiment shows that SRD5A3 is the diverged human ortholog of the yeast DFG10 gene and suggests a specific role for SRD5A3 in protein glycosylation compared with other family members.

Phylogenetic analysis of proteins with a steroid 5 alpha-reductase domain from multiple species indicates that this steroid reductase family can be separated in three main groups consisting of 1] the SRD5A1-SRD5A2 group, 2] the SRD5A3 group containing DFG10 and 3] the GPSN2-SRD5A2L2 group (Figure S3) supporting the idea that different classes of lipids can be substrates for these enzymes and suggesting that the substrate of the enzyme encoded by the common ancestral gene was potentially not a steroid.

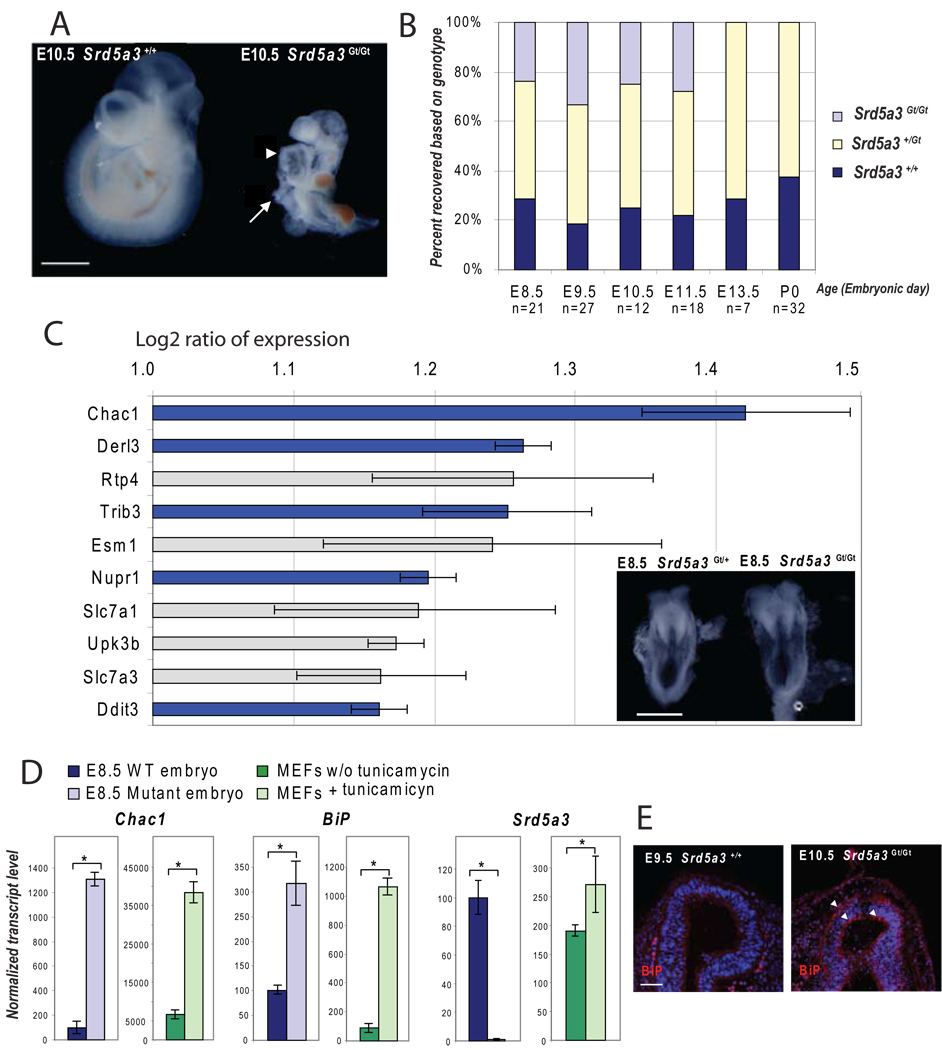

Srd5a3 mutation is lethal in mouse and results in an activation of the unfolded protein response pathway

We found that mice homozygous for a LacZ gene trap (Gt) insertion in intron 3 of Srd5a3 were recovered at embryonic stages, up to E12.5 but not beyond (Figure 4A–B). At E10.5, Srd5a3Gt(betaGeo)703Lex/Gt(betaGeo)703Lex embryos (abbreviated Srd5a3Gt/Gt) were smaller and failed to undergo axial rotation observed at E8.5 in wt litter mates. Analysis using β- gal colorimetric staining in asymptomatic heterozygous carriers showed strong expression in the yolk sac, eyes, heart and neural tube (Figure S4A–D). In keeping with this, homozygous mutants frequently presented dilated hearts (Figure 4A) and open neural tubes, which is consistent with the broad phenotypes observed in patients.

Figure 4. Characterization of homozygous Srd5a3Gt/Gt gene trap mouse embryos.

(A) Phenotype at E10.5 shows failure to rotate, ventral body wall defect (arrow) and dilated heart (arrowhead). Scale bar 1 mm.

(B) Graphic representation of the genotype obtained from the progeny of heterozygous mating, with lethality appearing between E11.5 and E13.5.

(C) Genes overexpressed in Srd5a3Gt/Gt at E8.5 detected using 44k mouse genome oligo microarray (1 is the Log 2 of a 2 fold expression increase, error bars represent the mean +/− standard deviation from 4 independent experiments). Among 10 of the most upregulated genes, 5 (in blue) are involved in the unfolded protein response pathway UPR). Morphology of heterozygous and homozygous Srd5a3 mutant embryos at E8.5, before embryo axial rotation. Scale bar 500 µm.

(D) Real-time RT-PCR confirming activation of the UPR pathway (Errors bars are means +/− standard deviations, asterisks indicate p<0.05, n=3).

(E) Immunofluorescence staining showing expression of BiP protein (red), a marker of the UPR pathway activation, in the neuroepithelium of the forebrain vesicle (arrowheads). Scale bar 50µm.

See also Figure S4.

To identify the mis-regulated pathways underlying these developmental defects, we carried out expression microarray analysis in Srd5a3Gt/Gt embryos versus wt litter mates before morphological differences appeared (Figure 4C). Whole transcriptome analysis revealed that among the 50 most upregulated transcripts, 20% are involved in the regulation of the unfolded protein response (UPR) or are activated in this pathway (Table S1 and Table S2). An activation of the UPR pathway in E8.5 Srd5a3Gt/Gt embryos was confirmed by real-time RT-PCR and using E9.5 mouse embryonic fibroblast cell line treated with tunicamycin as a positive control (activates the UPR pathway by blocking N-glycosylation; Figure 4D). A marker of this pathway, BiP, is up-regulated at the transcript and protein levels in Srd5A3Gt/Gt embryos, with a particularly high expression in neuroepithelial cells (Figure 4E). Srd5a3 expression was not detected in mutant embryos; however in cells inhibited for N-glycosylation by tunicamycin treatment, its expression increased significantly (Figure 4D). We also confirmed UPR activation by determining enrichment of gene ontology (GO) categories by all the genes significantly mis-regulated in Srd5A3Gt/Gt embryos compared with littermate controls. UPR was the biological process most significantly enriched for the genes upregulated (Table S3), whereas genes involved in general cellular metabolic processes and specific embryonic developmental program like regionalization were the most significantly downregulated (Table S3). These observations suggest that Srd5a3 is required for ER protein folding, a primary role of N-glycan during development.

DFG10 and SRD5A3 are necessary for conversion of polyprenol to dolichol in yeast, mouse and human

During the de novo synthesis of dolichol in eukaryotes, the farnesyl pyrophosphate (FPP), a product of the mevalonate pathway, is elongated by its successive condensation with isopentenyl pyrophosphate (IPP), catalyzed by a cis-isopentenyltransferase named dehydrodolichyl diphosphate synthase (DHDD) (Figure 5A). According to the current model, when the chain reaches target length, the pyrophosphate and phosphate groups are removed, although the phosphatases are not yet identified (Kato et al., 1980; Wolf et al., 1991). The alpha-isoprene unit of polyprenol is subsequently reduced by an NADPH- dependent microsomal reductase (Sagami et al., 1993), but the enzyme involved has not been identified. Finally, a dolichol kinase (hDK), mutated in CDG-Im, transfers phosphate from CTP to dolichol (Allen et al., 1978; Kranz et al., 2007). The unidentified polyprenol reductase enzyme made SRD5A3 a likely candidate for this function.

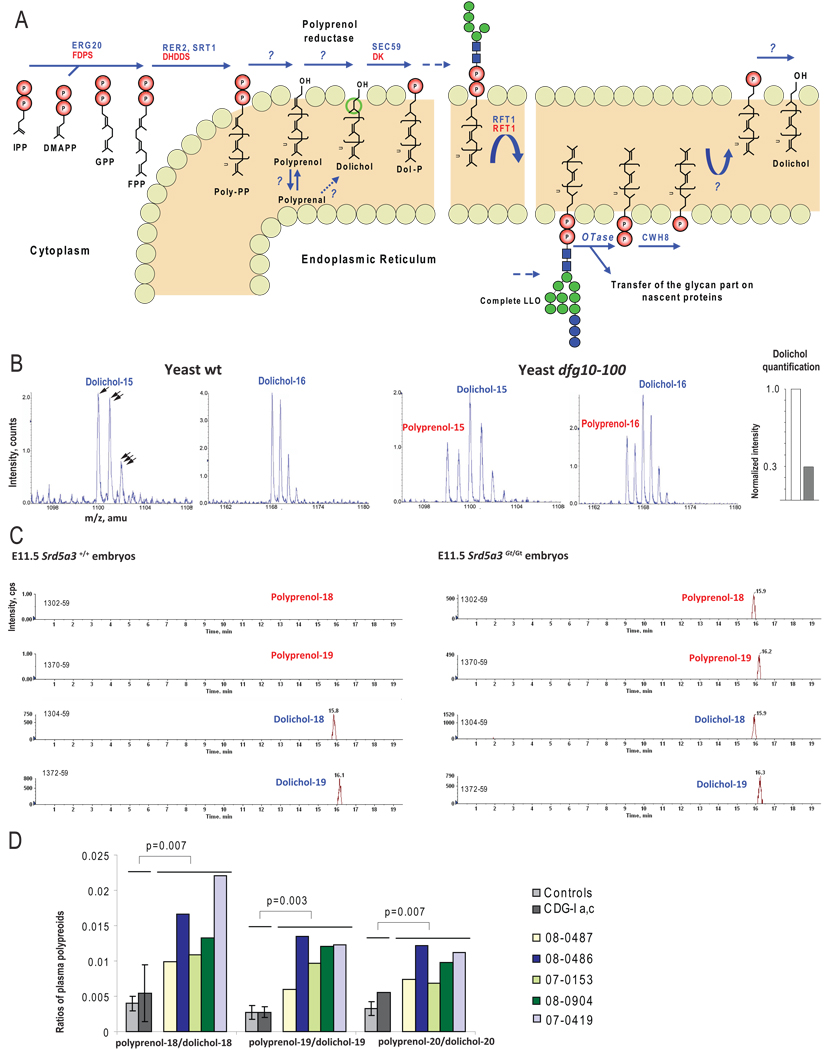

Figure 5. Analysis of polyprenols and dolichols, in yeast, mouse and human, using LC-MS.

(A) De novo biosynthesis and recycling of dolichol in eukaryotic cells with the yeast (in blue) and human (in red) enzymes involved. Isopentenylpyrophosphate (IPP) is the building block for all polyprenoids. IPP molecules are added sequentially in trans configuration, on dimethylallyl pyrophosphate (DMAPP) via the farnesyl pyrophosphate synthase (ERG20/FDPS) to form geranyl pyrophosphate (GPP) and then farnesyl pyrophosphate (FPP). More IPP units are then added in cis-configuration on FPP by the cis-prenyl transferases (RER2, SRT1/DHDDS), producing long polyprenoids that are embedded in the ER membrane. Once the final length is reached, both phosphate residues are released by unidentified phosphatases. The alpha-isoprene unit of the polyprenol is subsequently reduced by an NADPH-dependent microsomal reductase. For this step, the corresponding aldehydes have also been suggested as intermediates (Sagami et al., 1996). Finally the dolichol-specific kinase (SEC59/DK) transfers a phosphate from CTP to dolichol. Dol-P is used to build the lipid linked oligosaccharide (LLO). Once the oligosaccharide structure is transferred to specific asparagine residues, Dol-P is release on the luminal leaflet of the ER and dephosphorylated by a pyrophosphatase (CWH8).

(B) Mass spectra of Dolichol-15,16 in wt and dfg10–100 yeast strains showing accumulation of corresponding polyprenols in the mutant strain. Single, double and triple arrows highlight natural isotopic distribution, each offset by one atomic mass unit (amu). Polyprenol was detected only in mutant (red), by identification of a spectrum that partially overlapped with dolichol. Quantification of the dolichol content of yeast mutant indicates 70% reduction (following subtraction of polyprenol isotopic contribution, see methods, white bar = wt, grey bar = mutant).

(C) Scans of Dolichol-18,19 in wt and E11.5 Srd5a3Gt/Gt embryos showing the accumulation of corresponding polyprenols in the mutant embryos.

(D) Ratio of polyprenol-18,19,20 on dolichol-18,19,20 calculated with lipid plasma level from control and SRD5A3 mutated patients, showing a significant increase of these ratios compared to controls (n=10) and other types of CDG (n=4). Error bars represent the mean +/− standard deviation. Two-tailed student’s t-test was used for statistical analysis. Color bars represent individual measurement for 5 patients with SRD5A3 mutation. Error bar was not generated for pol-20/dol-20 ratio in the group CDGI-a,c as polyprenol levels were undetectable in 3 of 4 patients.

To explore a disruption of the final step of dolichol biosynthesis in SRD5A3 or DFG10 mutated cells and to unequivocally identify the last step of dolichol synthesis, we used Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS) (Garrett et al., 2007) to analyze polyprenols in wt and dfg10–100 yeast strains, E11.5 wt and Srd5a3Gt/Gt mouse embryos, fibroblasts and leukocytes from controls and patients. Polyprenol was not detected in any samples of wt origin as reported (Swiezewska and Danikiewicz, 2005) but was easily detected in the yeast and mouse mutants, in the same molar range as the dolichol naturally present in control samples (Figure 5B and C), suggesting a block in the polyprenol reduction step. In reference to an internal standard, by correcting polyprenol isotopic contribution, we detected a 70% decrease in dolichol in the dfg10–100 mutant compared to the wt yeast from the same background (Figure 5B, right end). Given these striking results in both mouse and yeast, we were surprised to find no clear change in prenol profiles in patient fibroblasts or leukocytes (data not shown). Because one possible explanation might be that the normal exogenous fetal calf serum used in tissue culture supplied dolichol to overcome this metabolic block, we instead analyzed directly patient fresh plasma. We found an increased level of polyprenoids in patients’ samples versus controls and in other CDG-I patients with a significant increased of polyprenols-18,19,20/dolichols-18,19,20 ratios (Figure 5D) indicating a defect in polyprenols metabolism in all organisms tested.

SRD5A3 promotes the reduction of polyprenol to dolichol

We next tested whether SRD5A3 was capable of reducing polyprenol to dolichol. We assessed polyisoprenoid levels in yeast transformed with vectors expressing the human and the yeast enzymes (Figure 6A–E), cultured in minimal media and harvested during the log phase. The important accumulation of polyprenol detected in the dfg10–100 strain (Figure 6B), is efficiently and specifically corrected in yeast transformed with the SRD5A3 gene (Figure 6D) compared to other human steroid 5-alpha reductases (Figure S5) whereas a mutant SRD5A3 (H296G) encoding an enzyme predicted to be inactive (Wigley et al., 1994) did not show any reduction of the accumulated polyprenol (Figure 6E). To evaluate if SRD5A3 was able to facilitate polyprenol reduction, we used lysates of transfected HEK293T cells overexpressing tagged SRD5A3. Exogenous polyprenol-18 was added in a buffer containing different detergents and mixed with lysates containing NADPH (Figure 6F–H’). Some exogenous polyprenol-18 was elongated to polyprenol-19, indicating a good incorporation of this lipid in the protein-lipid complexes from the lysate. The most efficient in vitro reduction was obtained with 0.1% Triton-X100; the reduction efficiency by the lysate of transfected cells with an empty vector was comparable with the previously described assay (Sagami et al., 1993). In control HEK293T cells, we found ∼28% exogenous polyprenol reduced to dolichol, whereas in lysates over-expressing WT SRD5A3, we found ∼67% reduction, (Figure 6F–H’ and Figure S6E). These results suggest that transfected SRD5A3 promotes efficient reduction of polyprenol.

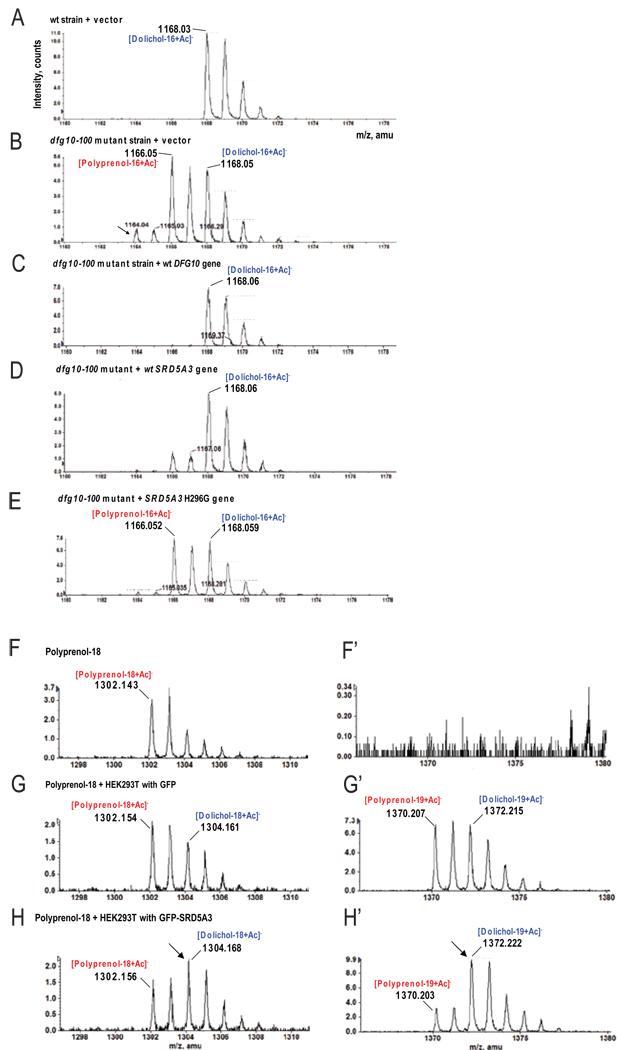

Figure 6. In vivo and in vitro polyprenol reduction promoting activity of SRD5A3.

(A–E) LC-MS analysis of lipid extract from yeast cultured in minimal media.

(A) Only dolichol is detected in wt yeast strains transformed with pYX212 empty vector.

(B) In dfg10–100 strain transformed with pYX212 empty vector, accumulation of polyprenol relative dolichol is evident. An additional compound (arrows) was tentatively identified as polyprenal, previously suggested as an intermediate in yeast during in vitro dolichol biosynthesis (Sagami et al., 1996).

(C) In the dfg10–100 strain transformed with wt DFG10 gene, no polyprenol accumulation was detected.

(D) Transformation of the dfg10–100 strain with the human SRD5A3 gene corrects polyprenol accumulation, although low levels are still detected.

(E) Transformation of the dfg10–100 strain with the human SRD5A3 enzymatically null H296G mutation fails to correct the polyprenol accumulation.

(F–H) LC-MS analysis of a lipid extract from an in vitro experiment performed with the exogenous substrate, polyprenol-18, in which cell lysates were used as the source of enzyme.

(F,F’) Polyprenol-18 spectrum after incubation in the reaction buffer without cell lysate. No polyprenol-19 or any forms of dolichol are evident.

(G,G’) After incubation with HEK293T cell lysate transfected with GFP, part of polyprenol-18 is elongated in polyprenol-19 and 28% is reduced to the corresponding dolichol.

(H,H’) In presence of lysate from cell over-expressing GFP-SRD5A3, 67% of the initial polyprenol is reduced to dolichol (arrows). Both cell lysates show similarly elongation of polyprenols.

DISCUSSION

Biological activity of SRD5A3

SRD5A3 sequence predicts a steroid 5-alpha steroid reductase domain, and some enzymes with this domain are able to reduce a variety of steroid hormones with a delta4,5, 3-oxo structure (Russell and Wilson, 1994). Mutation of the SRD5A2 gene in human causes male pseudohermaphroditism as a result of an enzymatic block of testosterone to dihydrotestosterone conversion (Andersson et al., 1991), mutation of the Srd5a1 gene in mice affects reproduction and parturition suggesting involvement in androgen metabolism (Mahendroo and Russell, 1999). Interestingly, a previous study suggested that cell extract containing over-expressed SRD5A3 was able to reduce testosterone to dihydrotestosterone (Uemura et al., 2008), albeit at a slow rate.

However, both our biochemical and clinical investigations in the patients with SRD5A3 mutations indicate that the nature of the substrate of the SRD5A3 enzyme is not related to the steroids. Our patients displayed no abnormal sexual abnormalities which would have suggested a primary defect of steroid metabolism. Moreover, karyotype analysis excluded the possibility of sex reversal in all (not shown). These observations lead us to hypothesize that the in vivo substrate of SRD5A3 could be a different lipid. Polyprenols share a common origin with cholesterol because they are also built from isoprene units.

Another enzyme with a predicted steroid 5-alpha reductase domain, Tsc13/GPSN2, has been shown to be an enoyl reductase involved in the elongation of very long chain fatty acids (Kohlwein et al., 2001). This study also illustrates that the predicted steroid 5-alpha reductase domain is involved in the reduction of a non-steroid lipid, and suggests that the full spectrum of lipid reduction mediated by steroid 5-alpha reductase-like enzymes need further evaluation.

Current models for dolichol biosynthesis

Several mechanisms have been proposed for the last steps of dolichol biosynthesis. One postulated an initial dephosphorylation of polyprenol diphosphate followed by reduction to Dol-P, then dephosphorylation of Dol-P to produce dolichol (Chojnacki and Dallner, 1988). However, several studies demonstrated the phosphorylation of dolichol as the major pathway for the production of Dol-P (Heller et al., 1992; Rossignol et al., 1983). A second proposal suggested that the final condensation reaction of Pol-PP uses isopentenol instead of isopentenyl-PP. In this reaction, Pol-PP is directly transformed to a one isoprene unit longer dolichol, thus circumventing the dephosphorylation steps (Ekstrom et al., 1987). The third proposal is the most widely accepted (Figure 5A) based on the finding of high concentrations of polyprenol during the initial phase of dolichol biosynthesis (Ekstrom et al., 1984) and the detection of a basal polyprenol reductase activity, in vitro (Sagami et al., 1993). However, the reductase postulated in this reaction had not been identified and thus these models could not be directly evaluated. Our results suggest that SRD5A3 is the polyprenol reductase, which is consistent with the last model, confirming that the reduction of polyprenol is the major pathway for dolichol biosynthesis.

Residual dolichol in SRD5A3 mutants

Dolichol was still detected in human, mouse and yeast SRD5A3/DFG10 mutants, suggesting the existence of another de novo biosynthetic pathway for dolichol production. The presence of dolichol in these mutants is not explained by dietary contribution, which was reported to be negligible in rat (Keller et al., 1982) and the nature of the mutations in human, mouse and yeast suggest that these organisms have null mutations for this gene. These observations indicate the existence of an alternative pathway for de novo synthesis of dolichol in eukaryotic cells. Disruption of LLO biosynthesis due to mutation in Dpagt1 in mouse results in embryonic lethality at E5 (Marek et al., 1999), a more severe phenotype than observed in Srd5a3 mutant mouse embryos, consistent with an alternative pathway. One candidate is the TSC13 gene, the only other gene in S. cerevisiae encoding a steroid 5-alpha reductase domain (Pfam database). We tested whether the tsc13 mutant had abnormal CPY glycosylation, and whether the dfg10/tsc13 double mutant showed further increase of the polyprenol/dolichol ratio, but found no effect of either (Figure S3), suggesting the alternative pathway for dolichol synthesis is independent of these genes. Interestingly, among the pathways activated in embryonic mouse mutants was the mevalonate pathway, including the isoprenoid biosynthetic enzymes (Table S1 and Table S2). This could suggest a positive feedback mechanism, which might help organisms overcome a partial block of these pathways.

Phenotypic spectrum resulting from disruption of dolichol metabolism

Tissues affected in patients with SRD5A3 mutations, such as nervous system, ocular structures, skin, or coagulation factors reflect sensitivity for alteration in N-glycosylation. Such congenital defects and the detection of a restricted expression pattern of Srd5a3 in mouse embryo suggest a spatial-temporal requirement during development. N-glycan number and branching regulate surface glycoprotein levels, affecting cell proliferation and differentiation (Lau et al., 2007). N-glycosylation may help regulate specific developmental pathways yet to be discovered.

Although we find defects in the N-glycosylation pathway, dolichol is also required for the synthesis of O-mannose linked glycans, C-mannosylation, and glycophospholipid anchor synthesis, and some of the pathology may derive from these defects, not explored here. Furthermore, little is known about the glycosylation-independent functions of dolichol, considered as a general membrane component in mammalian cells (Rip et al., 1985).

The pathogenesis and phenotypic specificity of CDGs deserves further investigations. However, our results point to an unsuspected role for a steroid reductase in the pathogenesis of one type of CDG, presumably mediated by a requirement for dolichol synthesis.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Genome mapping

All patients were enrolled according to approved human subjects protocol at respective institutions. DNA was extracted from peripheral blood leukocytes by salt extraction, genotyped with the Illumina Linkage IVb mapping panel (Murray et al., 2004) and analyzed with easyLINKAGE-Plus software (Hoffmann and Lindner, 2005). Parameters were set to autosomal recessive with full penetrance, and disease allele frequency of 0.001. Genomic regions with LOD scores over 2 were considered as candidate intervals. Linkage simulations were performed with Allegro 1.2c under the same parameters, with 5000 markers at average 0.64 cM intervals, codominant allele frequencies, and parametric calculations (Hoffmann and Lindner, 2005).

Mutation and CDG screening

We performed direct bidirectional sequencing of the five coding exons and splice junction sites of SRD5A3 via BigDye Terminator cycle sequencing (Applied Biosystems). We screened 31 patients with CDG-Ix and 7 patients from a cohort with CDG-Ix and either strong clinical overlap such as severe congenital eye malformation and/or indications for a dolichol-phosphate biosynthesis defect. Clinical description of patients 08–0486, 08–0487 and 07–0419 was previously reported, corresponding respectively to patients 3, 5 and 7 (Morava et al., 2008) and 25, 26 and 27 (Morava et al., 2009). CDG was diagnosed by affinity chromatography and mass spectrometry analysis of transferrin (O’Brien et al., 2007) or by using transferrin isoelectric focusing (de Jong et al., 1994).

GlcNAc-transferase assays in fibroblasts

Skin fibroblasts from the patients and controls were cultured in DMEM 10%FCS. Microsomal membranes were prepared as described (Thiel et al., 2002), and suspended in 20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.1, 10 mM MgCl2 and 1 mM DTT.

Assay I. To measure the transfer of GlcNAc from UDP-GlcNAc to endogenous lipid acceptor in microsomal membranes, the reaction contained 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 0.1 µCi UDP-[14C]GlcNAc (spec. activity 262 mCi/ mmol), 15 mM MgCl2, 0.8 mM DTT, 26% glycerol and 150 µg protein in a final volume of 60 µl. After 15 min at 24°C the reaction was stopped with chloroform/methanol (3/2, by vol.) and processed by phase partitioning (Sharma et al., 1982). Radioactive glycolipids were separated on silica gel 60 plates (Merck) developed in chloroform/methanol/water (65/25/4, by vol.). Radioactivity was detected and quantified by phosphorimager (Molecular Dynamics).

Assay II. To determine the transfer to exogenous Dol-P the reaction contained 3.6 µg Dol-P, 2.4 mM diheptanoyl-phosphatidylcholine, 38 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 0.1 µCi UDP-[14C]GlcNAc (spec. activity 262 µCi/ mmol), 11 mM MgCl2, 0.7 mM DTT, 25% glycerol and 150 µg protein in a final volume of 60 µl. Incubation and processing of the reaction was as in assay I.

Construction of DsRed-SRD5A3 and GFP-SRD5A3 expression plasmids

The ORF of SRD5A3 was amplified from a human fetal brain cDNA library and cloned in phrGFP II-N (Stratagene) and pDsRed2-C1 (Clontech) vectors. Site-directed mutagenesis was performed with QuickChange II site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene) according to manufacturer’s instructions.

Analysis of Srd5a3 Gt/Gt embryos, microarray experiments and quantitative PCRs

Frozen embryos (129/SvEvBrd × C57BL6/J mix) carrying a gene trap insertion in one allele of Srd5a3 were obtained from Lexicon and transferred in pseudo-pregnant female (Renard and Babinet, 1984). Genotyping was performed by PCR using yolk sac extracted DNA. Whole transcriptome analysis was performed using 44k Agilent genome oligo microarray kit with four embryos Srd5a3Gt/Gt and four littermate controls from two different litters. For these experiments, E8.5 embryos, which had not started the turning process and did not yet show morphological defect were chosen. Real-time PCR reactions were performed in the LightCycler 480 system (Roche) using the SYBR Green I Master Kit (Roche). Seven of the eight genes found misregulated with the microarray experiment and tested by real-time PCR were found to be comparably and significantly misregulated. Animals were used in compliance with approved institutional policies.

Mass spectrometry analysis of yeast and mouse samples

Lipid extraction (Bligh and Dyer, 1959) and LC-MS analysis was performed as described (Garrett et al., 2007). For quantitative measurements, nor-dolichol (Avanti Polar Lipids) (Garrett et al., 2007) was added to the sample before lipid extraction. For a detailed description, please see the Supplemental experimental procedures.

Analysis of plasma polyprenoids

Plasma (500 uL) samples from controls (n=10), all with normal transferrin isofocusing profile), CDG-I patients with known defect (n=4) and SRD5A3 patients (n=5) were subjected to saponification (Yasugi and Oshima, 1994) by addition of 5M KOH in water (500 uL) and MeOH (1500 uL) for 1h at 100°C under nitrogen atmosphere. Lipids were extracted with hexane (2× 1.5 mL), the organic phase was washed with 1.5 mL water and dried. Samples were dissolved in hexane-MeOH (100 uL, 1:2 v/v) and 5 uL was injected on a 50×2mm monolythic column (C18, Onyx) coupled to a Quattro LC-ESI Tandem mass spectrometer (MicroMass). Polyprenoids were eluted with a MeOH / Isopropanol gradient containing 1% 50 mM LiI. MRM transitions [Dol-n]Li+ => 162+ and [Pren-n]Li+ => [Pren-n-H2O]Li+ were used to calculate response areas/mL plasma of respectively dolichols and polyprenols (n=number of isopentenyl units) (D’Alexandri et al., 2006).

Polyprenol reduction assay

The assay was performed as a modification of the procedure described previously (Sagami et al., 1993). The reaction mixture consisted of 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 1 mM DTT, 50 mM KF, 20% glycerol, 1 mM MgCl2, 0.1% Triton-X100 and 4 µg/ml of polyprenol C90, previously dissolved in ethanol. After 15 minutes sonication in a bath apparatus, the reaction was started with the addition of 5 mM NADPH and 700 µg of crude cell-extract proteins, to a final volume of 250 µl. Reactions were incubated for 12h at 37°C. Samples were lipid extracted (Bligh and Dyer, 1959) after mixing with an internal standard of nor-dolichol, and analyzed by LC-MS.

Bioinformatics

Phylogenetic tree representation was done using phylogeny (Dereeper et al., 2008). (http://www.phylogeny.fr/version2_cgi/index.cgi). Topology prediction was performed with TMHMM, a program for predicting membrane-spanning segments based on Hidden Markov Model (http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/TMHMM/). Pfam database was used to identify proteins with Steroid 5-alpha-reductase domain (PF02544) (http://pfam.sanger.ac.uk//family/PF02544).

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank G.R. Fink, A. Jansen, F. Karst, K. Gable, T.M. Dunn, R. Kolodner for providing yeast strains and helpful advice. We are grateful to J.H. Lin for valuable discussion. We thank D. Matern and the Mayo Clinic for providing complete results of patients’ transferrin analysis and also C. Sault for additional clinical results from family CVH-385. We thank UCSD microscope core (P30 NS047101 and DK80506) and BIOGEM core for help in imaging and microarray data analysis. A. de Rooij and K. Huyben are gratefully acknowledged for technical assistance. HHF is a Sanford Research Professor. He and BN are supported by the Rocket Fund, R01 DK55615 and the Sanford Children’s Health Research Center. Financial support from Euroglycanet (LSHM-CT2005-512131) to RW and Metakids and the Netherlands Brain Foundation to DL are kindly acknowledged. LL was supported by grants from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft and the Körber-Stiftung. The mass spectrometry facility in the Department of Biochemistry of the Duke University Medical Center and ZG are supported by the LIPID MAPS Large Scale Collaborative Grant number GM-069338 from NIH. VC is supported by a fellowship from FRM, and JGG is an Investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

SUPPLEMENTAL DATA

Supplemental data including three tables, six supplementary figures, and supplementary methods can be found with this article online at http://www.cell.com.

REFERENCES

- Aebi M, Hennet T. Congenital disorders of glycosylation: genetic model systems lead the way. Trends Cell Biol. 2001;11:136–141. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(01)01925-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aggarwal S, Thareja S, Verma A, Bhardwaj TR, Kumar M. An overview on 5alpha-reductase inhibitors. Steroids. 2009 doi: 10.1016/j.steroids.2009.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Gazali L, Hertecant J, Algawi K, El Teraifi H, Dattani M. A new autosomal recessive syndrome of ocular colobomas, ichthyosis, brain malformations and endocrine abnormalities in an inbred Emirati family. Am J Med Genet A. 2008;146:813–819. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.32114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alber T, Kawasaki G. Nucleotide sequence of the triose phosphate isomerase gene of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Mol Appl Genet. 1982;1:419–434. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersson S, Berman DM, Jenkins EP, Russell DW. Deletion of steroid 5 alpha-reductase 2 gene in male pseudohermaphroditism. Nature. 1991;354:159–161. doi: 10.1038/354159a0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behrens NH, Leloir LF. Dolichol monophosphate glucose: an intermediate in glucose transfer in liver. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1970;66:153–159. doi: 10.1073/pnas.66.1.153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bligh EG, Dyer WJ. A rapid method of total lipid extraction and purification. Can J Biochem Physiol. 1959;37:911–917. doi: 10.1139/o59-099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chavan M, Lennarz W. The molecular basis of coupling of translocation and N-glycosylation. Trends Biochem Sci. 2006;31:17–20. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2005.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chojnacki T, Dallner G. The biological role of dolichol. Biochem J. 1988;251:1–9. doi: 10.1042/bj2510001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Alexandri FL, Gozzo FC, Eberlin MN, Katzin AM. Electrospray ionization mass spectrometry analysis of polyisoprenoid alcohols via Li+ cationization. Anal Biochem. 2006;355:189–200. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2006.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Jong G, van Noort WL, van Eijk HG. Optimized separation and quantitation of serum and cerebrospinal fluid transferrin subfractions defined by differences in iron saturation or glycan composition. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1994;356:51–59. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-2554-7_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dereeper A, Guignon V, Blanc G, Audic S, Buffet S, Chevenet F, Dufayard JF, Guindon S, Lefort V, Lescot M, et al. Phylogeny.fr: robust phylogenetic analysis for the non-specialist. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:W465–W469. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eklund EA, Freeze HH. The congenital disorders of glycosylation: a multifaceted group of syndromes. NeuroRx. 2006;3:254–263. doi: 10.1016/j.nurx.2006.01.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekstrom TJ, Chojnacki T, Dallner G. Metabolic labeling of dolichol and dolichyl phosphate in isolate hepatocytes. J Biol Chem. 1984;259:10460–10468. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekstrom TJ, Chojnacki T, Dallner G. The alpha-saturation and terminal events in dolichol biosynthesis. J Biol Chem. 1987;262:4090–4097. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeze HH. Genetic defects in the human glycome. Nat Rev Genet. 2006;7:537–551. doi: 10.1038/nrg1894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garrett TA, Guan Z, Raetz CR. Analysis of ubiquinones, dolichols, and dolichol diphosphate-oligosaccharides by liquid chromatography-electrospray ionization-mass spectrometry. Methods Enzymol. 2007;432:117–143. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(07)32005-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grunewald S, Matthijs G. Congenital disorders of glycosylation (CDG): a rapidly expanding group of neurometabolic disorders. Neuropediatrics. 2000;31:57–59. doi: 10.1055/s-2000-7487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haeuptle MA, Hennet T. Congenital disorders of glycosylation: an update on defects affecting the biosynthesis of dolichol-linked oligosaccharides. Hum Mutat. 2009;30:1628–1641. doi: 10.1002/humu.21126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasilik A, Tanner W. Carbohydrate moiety of carboxypeptidase Y and perturbation of its biosynthesis. Eur J Biochem. 1978;91:567–575. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1978.tb12710.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helenius A, Aebi M. Intracellular functions of N-linked glycans. Science. 2001;291:2364–2369. doi: 10.1126/science.291.5512.2364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann K, Lindner TH. easyLINKAGE-Plus--automated linkage analyses using large-scale SNP data. Bioinformatics. 2005;21:3565–3567. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaeken J, Hennet T, Matthijs G, Freeze HH. CDG nomenclature: time for a change! Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1792:825–826. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2009.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaeken J, Matthijs G. Congenital disorders of glycosylation: a rapidly expanding disease family. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet. 2007;8:261–278. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genom.8.080706.092327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones MB, Rosenberg JN, Betenbaugh MJ, Krag SS. Structure and synthesis of polyisoprenoids used in N-glycosylation across the three domains of life. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1790:485–494. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2009.03.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller RK, Jehle E, Adair WL., Jr The origin of dolichol in the liver of the rat. Determination of the dietary contribution. J Biol Chem. 1982;257:8985–8989. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohlwein SD, Eder S, Oh CS, Martin CE, Gable K, Bacikova D, Dunn T. Tsc13p is required for fatty acid elongation and localizes to a novel structure at the nuclear-vacuolar interface in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21:109–125. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.1.109-125.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau KS, Partridge EA, Grigorian A, Silvescu CI, Reinhold VN, Demetriou M, Dennis JW. Complex N-glycan number and degree of branching cooperate to regulate cell proliferation and differentiation. Cell. 2007;129:123–134. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.01.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahendroo MS, Russell DW. Male and female isoenzymes of steroid 5alpha-reductase. Rev Reprod. 1999;4:179–183. doi: 10.1530/ror.0.0040179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marek KW, Vijay IK, Marth JD. A recessive deletion in the GlcNAc-1-phosphotransferase gene results in peri-implantation embryonic lethality. Glycobiology. 1999;9:1263–1271. doi: 10.1093/glycob/9.11.1263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morava E, Wosik H, Karteszi J, Guillard M, Adamowicz M, Sykut-Cegielska J, Hadzsiev K, Wevers RA, Lefeber DJ. Congenital disorder of glycosylation type Ix: review of clinical spectrum and diagnostic steps. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2008;31:450–456. doi: 10.1007/s10545-008-0822-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morava E, Wosik HN, Sykut-Cegielska J, Adamowicz M, Guillard M, Wevers RA, Lefeber DJ, Cruysberg JR. Ophthalmological abnormalities in children with congenital disorders of glycosylation type I. Br J Ophthalmol. 2009;93:350–354. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2008.145359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mosch HU, Fink GR. Dissection of filamentous growth by transposon mutagenesis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 1997;145:671–684. doi: 10.1093/genetics/145.3.671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishikawa A, Mizuno S. The efficiency of N-linked glycosylation of bovine DNase I depends on the Asn-Xaa-Ser/Thr sequence and the tissue of origin. Biochem J. 2001;355:245–248. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3550245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien JF, Lacey JM, Bergen HR., 3rd Detection of hypo-N-glycosylation using mass spectrometry of transferrin. Curr Protoc Hum Genet. 2007 doi: 10.1002/0471142905.hg1704s54. Chapter 17, Unit 17 14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renard JP, Babinet C. High survival of mouse embryos after rapid freezing and thawing inside plastic straws with 1–2 propanediol as cryoprotectant. J Exp Zool. 1984;230:443–448. doi: 10.1002/jez.1402300313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rip JW, Rupar CA, Ravi K, Carroll KK. Distribution, metabolism and function of dolichol and polyprenols. Prog Lipid Res. 1985;24:269–309. doi: 10.1016/0163-7827(85)90008-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz-Canada C, Kelleher DJ, Gilmore R. Cotranslational and posttranslational N-glycosylation of polypeptides by distinct mammalian OST isoforms. Cell. 2009;136:272–283. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.11.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell DW, Wilson JD. Steroid 5 alpha-reductase: two genes/two enzymes. Annu Rev Biochem. 1994;63:25–61. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.63.070194.000325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sagami H, Igarashi Y, Tateyama S, Ogura K, Roos J, Lennarz WJ. Enzymatic formation of dehydrodolichal and dolichal, new products related to yeast dolichol biosynthesis. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:9560–9566. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.16.9560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sagami H, Kurisaki A, Ogura K. Formation of dolichol from dehydrodolichol is catalyzed by NADPH-dependent reductase localized in microsomes of rat liver. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:10109–10113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma CB, Lehle L, Tanner W. Solubilization and characterization of the initial enzymes of the dolichol pathway from yeast. Eur J Biochem. 1982;126:319–325. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1982.tb06781.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sidbury R, Paller AS. What syndrome is this? CHIME syndrome. Pediatr Dermatol. 2001;18:252–254. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1470.2001.018003252.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swiezewska E, Danikiewicz W. Polyisoprenoids: structure, biosynthesis and function. Prog Lipid Res. 2005;44:235–258. doi: 10.1016/j.plipres.2005.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thiel C, Schwarz M, Hasilik M, Grieben U, Hanefeld F, Lehle L, von Figura K, Korner C. Deficiency of dolichyl-P-Man:Man7GlcNAc2-PP-dolichyl mannosyltransferase causes congenital disorder of glycosylation type Ig. Biochem J. 2002;367:195–201. doi: 10.1042/BJ20020794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vermeer S, Kremer HP, Leijten QH, Scheffer H, Matthijs G, Wevers RA, Knoers NA, Morava E, Lefeber DJ. Cerebellar ataxia and congenital disorder of glycosylation Ia (CDG-Ia) with normal routine CDG screening. J Neurol. 2007;254:1356–1358. doi: 10.1007/s00415-007-0546-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vleugels W, Haeuptle MA, Ng BG, Michalski JC, Battini R, Dionisi-Vici C, Ludman MD, Jaeken J, Foulquier F, Freeze HH, et al. RFT1 deficiency in three novel CDG patients. Hum Mutat. 2009;30:1428–1434. doi: 10.1002/humu.21085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wigley WC, Prihoda JS, Mowszowicz I, Mendonca BB, New MI, Wilson JD, Russell DW. Natural mutagenesis study of the human steroid 5 alpha-reductase 2 isozyme. Biochemistry. 1994;33:1265–1270. doi: 10.1021/bi00171a029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yasugi E, Oshima M. Sequential microanalyses of free dolichol, dolichyl fatty acid ester and dolichyl phosphate levels in human serum. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1994;1211:107–113. doi: 10.1016/0005-2760(94)90144-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.