Abstract

Sertoli cells are essential for testicular germ cell maintenance and survival. We made the unexpected observation that x-radiation (x-ray)–induced germ cell loss is attenuated by co-exposure with the Sertoli cell toxicant 2,5-hexanedione (HD). The mechanisms underlying this attenuation of germ cell apoptosis with reduced Sertoli cell support are unknown. The current study was performed to examine alterations in testicular gene expression with co-exposure to HD and x-ray. Adult male rats were exposed to HD (0.33 or 1%) in the drinking water for 18 days followed by x-ray (2 or 5 Gy), resulting in nine treatment groups. Testis samples were collected after 3 h and total messenger RNA was analyzed using Affymetrix Rat Genome 230 2.0 arrays. Normalized log2-expression values were analyzed using LIMMA and summarized using linear contrasts designed to summarize the aggregated effect, in excess of x-ray alteration, of HD across all treatment groups. These contrasts were compared with the overall linear trend expression for x-ray, to determine whether HD effects were agonistic or antagonistic with respect to x-ray damage. Overrepresentation analysis to identify biological pathways where HD modification of gene expression was the greatest was performed. HD exerted a significant influence on genes involved in cell cycle and cell death/apoptosis. The results of this study provide insight into the mechanisms underlying attenuated germ cell toxicity following HD and x-ray co-exposure through the analysis of co-exposure effects on gene expression, and suggest that HD pre-exposure reduces Sertoli cell supported germ cell proliferation thereby reducing germ cell vulnerability to x-rays.

Keywords: testis; x-radiation; 2,5-hexanedione; microarray; co-exposure

Environmental exposure to hazardous chemicals most often occurs as mixed exposures to more than one toxicant (Boekelheide, 2007). There is an emerging need for improved methods for risk assessment and a better understanding of toxicological consequences of mixed exposures. In addition to more traditional toxicological endpoints, microarray analysis is increasingly used as a tool for examining toxicological effects and mechanisms behind mixed exposures (Bartosiewicz et al., 2001; Hook et al., 2008; Rockett and Dix, 1999). These technologies are valuable because complex mixtures may interact in any number of ways, resulting in antagonistic, additive, or synergistic effects (Carpenter et al., 2002; Groten et al., 2001), complicating risk assessment of mixed exposures. When assessing mixture effects in the testis, there is the added complexity of the paracrine-interacting cell types that are necessary for successful spermatogenesis. Testicular toxicants may selectively target a single cell type, such as Sertoli cells or germ cells, with damage to either target resulting in germ cell apoptosis and spermatogenic failure.

Recent research in our laboratory has begun to investigate the consequences of mixed exposures in the testis. 2,5-hexanedione (HD) and x-radiation (x-ray) were used to establish an adult rat model of testicular co-exposure toxicity, which involves a 17-day priming exposure to HD in combination with half-body x-ray exposure on day 17 followed by necropsy 12 h later on day 18. X-radiation disrupts spermatogenesis by directly targeting germ cells. Exposure to x-ray causes free radical–induced DNA breaks in actively dividing spermatogonia, resulting in their apoptosis (Hasegawa et al., 1997). HD is a metabolite of the commonly used solvents n-hexane and methyl n-butyl ketone (2-hexanone) that causes Sertoli cell dysfunction by interfering with Sertoli cell microtubule assembly kinetics (Boekelheide et al., 2003). HD-induced testicular toxicity is unique in that there is a latency period between initiation of exposure and development of histopathologic alterations, with significantly altered testicular morphology apparent only after 2.5–3 weeks of exposure (reviewed by Boekelheide et al., 2003). The chemistry of HD partially explains the delayed toxicity, which is the result of a progression of subcellular events. HD interacts with tissue nucleophiles, including protein lysyl ϵ-amines, resulting in pyrrole formation and accumulation, followed by oxidation and cross-linking (reviewed by Boekelheide et al., 2003). At the end of an 18-day exposure period, as used in our co-exposure paradigm, HD-treated testes exhibit an increase in retained spermatid heads but no increase in germ cell apoptosis at the dose levels used (0.33 and 1%) (Moffit et al., 2007). More severe effects, such as vacuolization, decreased seminiferous tubule fluid formation, and germ cell apoptosis, are observed at later time points (4–5 weeks) after initiating exposure (Boekelheide et al., 2003). Sertoli cells are essential for germ cell maintenance and survival, yet surprisingly, the level of germ cell apoptosis in the testes of rats coexposed to HD and x-ray was significantly lower than that observed in rats exposed to x-ray alone. This HD-dependent attenuated germ cell death response was stage specific, with a significantly higher degree of apoptosis observed at stages II/III in x-ray alone compared with HD and x-ray combined exposure. These findings are reported in a companion paper by Yamasaki et al. (2010)

The goal of the current study was to improve our understanding of this attenuated co-exposure toxicity and identify potential mechanisms by examining global gene expression changes. Because HD pretreatment significantly altered the extent of acute x-ray–induced germ cell apoptosis, this study focused on the degree to which HD attenuated or enhanced the x-ray–induced deviation from the control level for both downregulated and upregulated gene expression. The primary goal of this data analysis approach was to determine if there is a trend toward enhancement or attenuation of x-ray–induced gene alterations by the priming exposure to HD, and to identify those genes that were either enhanced or attenuated. We found that HD significantly affected x-ray–induced expression of genes involved in cell cycle/cell division process, cell cycle/G1/S phase transition, and cell death/apoptosis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals.

Adult male Fischer 344 rats weighing 200–250 g were purchased from Charles River Laboratories (Wilmington, MA). Upon arrival, rats were acclimated for 1 week prior to use and maintained in a temperature- and humidity-controlled environment with a 12-h alternating dark-light cycle. All rats were housed in community cages with free access to water and Purina Rodent Chow 5001 (Farmer’s Exchange, Framingham, MA). The Brown University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee approved all experimental animal protocols in compliance with National Institute of Health guidelines.

Toxicant exposure.

Using a previously established treatment protocol (Markelewicz et al., 2004), HD was administered in drinking water ad libitum for 18 days at concentrations of 0.33 and 1%. On day 18, animals (n = 4 for each treatment group) were exposed to half-body radiation at a single dose of 2 or 5 Gy by a dose rate of 0.31 Gy/min using a RT 250 Philips kVp x-ray machine (Philips, Hamburg, Germany). The dose rate was estimated using a Radcal radiation monitor, model 2026C (Monrovia, CA). At 3 h after treatment with x-ray, following continued HD exposure, rats were euthanized by CO2 asphyxiation and half of the right testis was homogenized in Tri Reagent (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO), snap frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80°C. The remaining testis tissue was fixed in neutral-buffered formalin for histological examination.

RNA isolation and microarray hybridization.

RNA was isolated from testes homogenized in Tri Reagent using the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) following manufacturer’s protocol. Complementary DNA (cDNA) was synthesized from 2.5 μg total RNA and purified using the Affymetrix One-Cycle Target Labeling and Control Reagents kit (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA) according to manufacturer’s protocol. Equal amounts of purified cDNA per sample were used as the template for subsequent in vitro transcription reactions for complementary RNA (cRNA) amplification and biotin labeling using the Affymetrix GeneChip IVT labeling kit (Affymetrix) included in the One-Cycle Target Labeling kit (Affymetrix). The cRNA was purified and fragmented according to the protocol provided with the GeneChip Sample Cleanup module (Affymetrix). All GeneChip arrays (Rat Genome 230 2.0 arrays) were hybridized, washed, stained, and scanned using the Complete GeneChip Instrument System according to the Affymetrix Technical Manual.

Microarray data analysis.

Affymetrix CEL files were preprocessed using the R package GCRMA from Bioconductor to obtain genome-level expression values. The probe-level raw intensities were background corrected by GCRMA, quantile normalized and then summarized into log2-expression measures by Robust Multiarray Analysis. The resulting gene expression values for each of 31,099 genes were merged with netaffx build 29 of Rat Genome 230 2.0 annotation file. Associations with exposure were subsequently analyzed using standard linear model techniques; however, specific contrasts were used to aid interpretation in the context of the co-exposure design. A 3 × 3 factorial study design was used to facilitate the detection of nonlinear effects of exposure and interactions of co-exposure on messenger RNA (mRNA) expression. Because nine model degrees-of-freedom were inherent in the design, multiple patterns of exposure were possible, with some hard to characterize (notably those involving both nonlinearities and interaction). In order to account for nonmonotonicity in gene responses and summarize the HD effects above and beyond x-ray, a saturated linear model was used. Univariate (gene-specific) linear models were fit using the R/Bioconductor package limma (Smyth, 2004). To summarize linear model results, in particular to simplify the inputs for gene-set pathway analysis, the effects of HD in excess of x-ray were aggregated as the sum of all HD effects over the nine exposure cells. This is equivalent to the sum of the HD effects in the six cells having nonzero HD exposure, and reduces to 3× the sum of the two HD main effects + the four interaction terms (using the standard ANOVA treatment parameterization with the unexposed group as the reference level). The resulting summary statistic has the interpretation of an estimated aggregate HD effect in excess of x-ray, for example, upregulation (positive) or downregulation (negative) by HD. Additionally, the overall linear trend in x-ray was summarized by fitting the equivalent saturated model reparameterized using polynomials in exposure dose (i.e., linear and quadratic terms for each exposure together with their interactions), and extracting the linear x-ray term. To control for multiple comparisons, Q-values representing false discovery rates (FDR) were computed from the collection of all 31,099 p values using the qvalue package in R (Storey and Tibshirani, 2003).

Pathways analysis.

Functional classification of the differentially expressed genes was performed using the Ingenuity Pathways Analysis (IPA) knowledgebase (Ingenuity Systems, Redwood City, CA, IPA 6 content version 1602). The highest and middle-level functional categories of Ingenuity’s “Molecular and Cellular Functions” were used to define the gene sets (Supplementary table 1). Pathways analysis was performed using a one-tailed Fisher’s exact test (i.e., testing only for overrepresentation and ignoring underrepresentation, the latter of which is not readily interpretable). Genes were considered to be significantly over- or underexpressed with HD exposure (in excess of x-ray), if the HD summary contrast described above had Q-value less than 0.05. Pathways were ranked by p value and those with the lowest p values were selected for qualitative comparison.

RESULTS

Overview

Rats were euthanized 3 h after x-ray, a time point prior to detection of germ cell apoptosis (Yamasaki et al., 2010), in order to identify early changes in gene expression that precede the histopathologic manifestations of injury. Previous characterization of these histopathologic manifestations of injury at later time points surprisingly revealed that the priming exposure to HD, a Sertoli cell toxicant, attenuated the x-ray–induced germ cell toxicity across all dose combinations (Yamasaki et al., 2010). Because this HD pretreatment significantly modified the extent of acute x-ray–induced germ cell apoptosis, we focused on HD modification of x-ray–induced gene expression alterations in order to get a global view of the HD effects on gene expression. To determine how HD contributes to the gene expression profile during co-exposure, the HD effects were summarized across all treatment groups. From this model, we were able to estimate the degree to which HD modifies the x-ray–induced gene expression alterations. After extracting this contrast of interest, overrepresentation analysis to test for pathway-specific effects of HD on top of x-ray was performed using a one-tailed Fisher’s exact test.

Estimates of HD effects on gene expression

The 3 × 3 factorial study design of combined exposure to three different dose levels of HD (0, 0.33, and 1%) with three different dose levels of x-ray (0, 2, and 5 Gy), resulted in a total of nine different treatment groups: 0 HD/0 x-ray (control), 0 HD/2 Gy x-ray, 0 HD/5 Gy x-ray, 0.33 HD/0 x-ray, 0.33 HD/2 Gy x-ray, 0.33 HD/5 Gy x-ray, 1 HD/0 x-ray, 1 HD/2 Gy x-ray, 1 HD/5 Gy x-ray. Upon initial analysis, many genes were found to exhibit nonlinear trends; for example, the expression level for a gene was elevated at the low dose and decreased at the high dose. Consequently, it was necessary to summarize the HD effect in a way that accommodates nonmonotonicity. As described in the “Materials and Methods” section, a summary effect of HD in excess of x-ray was constructed by adding together the four interaction terms and 3× the sum of the two HD main effects (using the standard ANOVA treatment parameterization). The resulting statistic estimates the extent to which HD modifies gene expression above and beyond the x-ray–induced gene expression for each gene during co-exposure. This approach facilitates the identification of genes that exhibit HD modification of x-ray damage. Linear models were fit using LIMMA.

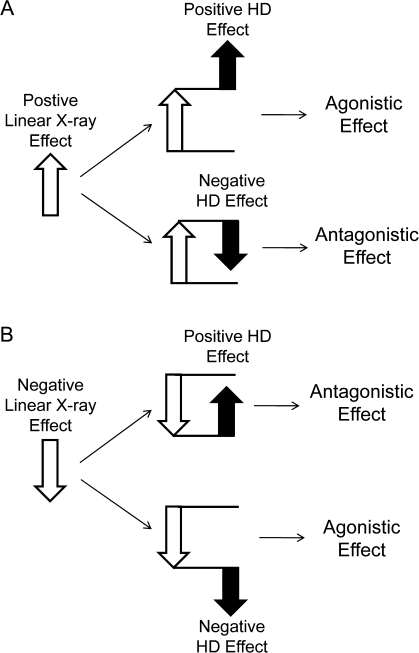

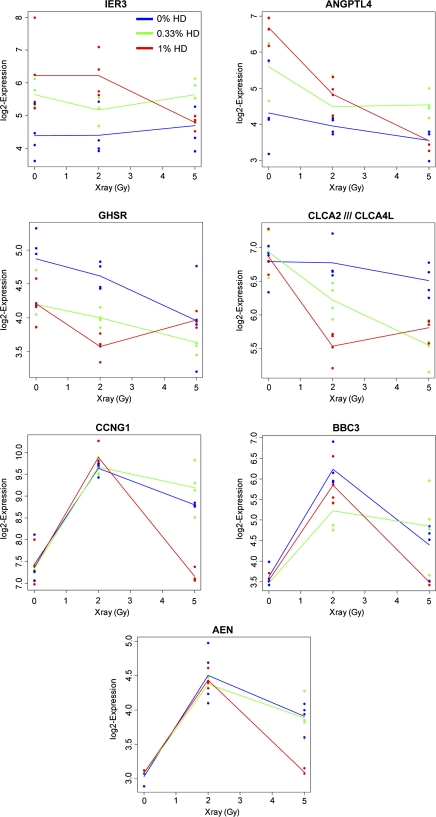

Significant modification of x-ray–induced gene expression alterations by HD pretreatment (FDR < 0.05) were observed for 55 genes (Table 1). X-ray linear effects on gene expression (obtained using polynomial parameterization of a saturated model, as described in the “Materials and Methods” section) are included to provide an indication of the expression induced by x-ray during co-exposure so that we can understand if the HD effect on top of x-ray is an attenuation or enhancement of these changes. A full list of all genes whose mRNA expression was significantly altered by x-ray can be found in Supplementary table 1. The type of interaction listed in Table 1 indicates how HD and x-ray together influence the expression of the gene. An agonistic interaction indicates that HD and x-ray alter the gene expression in the same way (either both increase or both decrease), which may be either additive or synergistic. An antagonistic interaction indicates opposing HD and x-ray effects, with one toxicant increasing gene expression, whereas the other decreases expression. These two different types of interactions are illustrated in Figure 1. Six of these genes were positively modified by HD. IER3 (immediate early response 3) and ANGPTL4 (angiopoietin-like 4) were the two genes most positively modified by HD. A negative modification of x-ray–induced gene alterations by HD was observed for the 49 other genes, with GHSR (growth hormone secretagogue receptor) and CLCA2 (chloride channel calcium activated 2) being strongly modified by HD in a negative way. Shown in Figure 2 are the gene expression profiles across all nine treatment groups for those four genes significantly modified by HD, as well as some representative genes significantly altered by x-ray during co-exposure (CCNG1, BBC3, and AEN). The example of ANGPTL4 expression in Figure 1 illustrates a negative linear x-ray effect on gene expression, showing a trend of decreasing gene expression as the x-ray dose increases from 0 to 5 Gy. However, a positive HD effect modifies ANGPTL4 gene expression, resulting in an attenuation of the x-ray–induced downregulation. Alternatively, CLCA2 demonstrates an enhancement of x-ray–induced downregulation with HD co-exposure.

TABLE 1.

Genes Significantly Modified by HD Coexposure

| Gene symbol | Gene description | HD effect | Linear x-ray effect | Type of interaction |

| IER3 | Immediate early response 3 | 6.7233 | −0.0574 | Antagonistic |

| ANGPTL4 | Angiopoietin-like 4 | 6.0360 | −0.2983 | Antagonistic |

| CTGF | Connective tissue growth factor | 3.6301 | −0.1609 | Antagonistic |

| ERRFI1 | ERBB receptor feedback inhibitor 1 | 1.9441 | −0.0471 | Antagonistic |

| TLE3 | Transducin-like enhancer of split 3 (E(sp1) homolog, Drosophila) | 1.8419 | −0.0077 | Antagonistic |

| MLF2 | Myeloid leukemia factor 2 | 1.0791 | 0.0135 | Agonistic |

| CD53 | CD53 molecule | −0.3673 | 0.0063 | Antagonistic |

| SSRP1 | Structure-specific recognition protein 1 | −0.3705 | −0.0393 | Agonistic |

| THAP4 | THAP domain containing 4 | −0.4876 | −0.0301 | Agonistic |

| MBD3 | Methyl-CpG-binding domain protein 3 | −0.5390 | −0.0220 | Agonistic |

| PRKAG2 | Protein kinase, AMP-activated, gamma 2 noncatalytic subunit | −0.5841 | −0.0284 | Agonistic |

| CAMSAP1 | Calmodulin-regulated spectrin-associated protein 1 | −0.6200 | −0.0391 | Agonistic |

| RANBP10 | RAN-binding protein 10 | −0.7035 | 0.0026 | Antagonistic |

| NASP | Nuclear autoantigenic sperm protein (histone binding) | −0.7701 | −0.0432 | Agonistic |

| LRRC48 | Leucine-rich repeat containing 48 | −0.7934 | −0.0725 | Agonistic |

| GPI | Glucose phosphate isomerase | −0.8050 | −0.1152 | Agonistic |

| FBP1 | Fructose-1,6-bisphosphatase 1 | −0.8497 | −0.0416 | Agonistic |

| DHRSX | Dehydrogenase/reductase (SDR family) X-linked | −0.8555 | −0.0908 | Agonistic |

| JTV1 | JTV1 gene | −0.8961 | −0.0647 | Agonistic |

| RGD1306603 | — | −0.9134 | −0.0432 | Agonistic |

| ITPKA | Inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate 3-kinase A | −0.9262 | −0.0571 | Agonistic |

| RGD1311084 | Similar to 1700113K14Rik protein | −0.9977 | −0.0894 | Agonistic |

| RGD1309730 | Similar to RIKEN cDNA B230118H07 | −0.9983 | −0.0825 | Agonistic |

| PGAM2 | Phosphoglycerate mutase elevated 2 | −1.0061 | −0.0485 | Agonistic |

| DNMBP | Dynamin-binding protein | −1.0160 | −0.0360 | Agonistic |

| PASK | PAS domain containing serine/threonine kinase | −1.0413 | −0.0475 | Agonistic |

| MRPS11 | Mitochondrial ribosomal protein S11 | −1.0454 | −0.0264 | Agonistic |

| RCG_20380 | Hypothetical protein LOC100125367 | −1.0698 | −0.0177 | Agonistic |

| DDI2 | DDI1, DNA-damage inducible 1, homolog 2 (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) | −1.1447 | −0.0276 | Agonistic |

| CNTF | Ciliary neurotrophic factor | −1.1486 | −0.0537 | Agonistic |

| FOXK1 | Forkhead box K1 | −1.1508 | −0.0395 | Agonistic |

| H2AFJ | H2A histone family, member J | −1.1984 | −0.0711 | Agonistic |

| RNPEP | Arginyl aminopeptidase (aminopeptidase B) | −1.2364 | −0.0427 | Agonistic |

| HDDC3 | HD domain containing 3 | −1.2622 | −0.1110 | Agonistic |

| PRSS21 | Protease, serine, 21 (testisin) | −1.2652 | −0.0599 | Agonistic |

| SHANK3 | SH3 and multiple ankyrin repeat domains 3 | −1.2974 | −0.0321 | Agonistic |

| PITPNM1 | Phosphatidylinositol transfer protein, membrane-associated 1 | −1.3852 | −0.1325 | Agonistic |

| CYGB | Cytoglobin | −1.3958 | 0.0049 | Antagonistic |

| MAP3K11 | Mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase kinase 11 | −1.4775 | −0.1093 | Agonistic |

| PEX14 | Peroxisomal biogenesis factor 14 | −1.4910 | −0.0197 | Agonistic |

| DNAH1 | Dynein, axonemal, heavy chain 1 | −1.5618 | −0.1265 | Agonistic |

| COMP | Cartilage oligomeric matrix protein | −1.6105 | −0.0754 | Agonistic |

| LMOD2 | Leiomodin 2 (cardiac) | −1.6165 | −0.0933 | Agonistic |

| LOC499124 | Mouse zinc finger protein 14-like | −1.6318 | −0.0278 | Agonistic |

| CAPG | Capping protein (actin filament), gelsolin-like | −1.6775 | −0.1963 | Agonistic |

| COL6A1 | Collagen, type VI, alpha 1 | −1.7034 | −0.0436 | Agonistic |

| HSPB1 | Heat shock 27 kDa protein 1 | −2.0133 | −0.0698 | Agonistic |

| DPP7 | Dipeptidyl-peptidase 7 | −2.0200 | −0.1500 | Agonistic |

| MACROD1 | MACRO domain containing 1 | −2.0658 | −0.1446 | Agonistic |

| ALKBH2 | alkB, alkylation repair homolog 2 (Escherichia coli) | −2.1629 | −0.0629 | Agonistic |

| CFC1 | Cripton, FRL-1, cryptic family 1 | −2.5058 | −0.0155 | Agonistic |

| LOC683980 | Similar to keratinocytes associated protein 3 | −2.9492 | −0.1152 | Agonistic |

| LOXL1 | Lysyl oxidase-like 1 | −3.1699 | −0.1629 | Agonistic |

| CLCA2 /// CLCA4L | Chloride channel calcium activated 2 /// chloride channel calcium activated 4-like | −3.2185 | −0.3286 | Agonistic |

| GHSR | Growth hormone secretagogue receptor | −3.3223 | −0.0963 | Agonistic |

Note. The genes included in this table meet the significance threshold of FDR < 0.05 for the HD Effect. An agonistic interaction indicates an HD effect and x-ray effect in the same direction, whereas an antagonistic interaction indicates an HD effect and x-ray effect in opposing directions.

FIG. 1.

HD and x-ray interactions at the gene level. Gene expression alterations were summarized across all nine treatment groups and a linear x-ray effect (open arrows) and an HD effect (black arrows) on co-exposure gene expression were determined. On top of a positive linear x-ray effect (A), a positive HD effect represents an agonistic effect on gene expression, whereas a negative HD effect is an antagonistic effect on gene expression. Similarly, on top of a negative linear x-ray effect (B), a positive HD effect is antagonistic, whereas a negative HD effect is agonistic.

FIG. 2.

Co-exposure effects on gene expression. Relative gene expression following exposure to 0% (blue line), 0.33% (green line) or 1% HD (red line) in combination with 0, 2 or 5 Gy x-ray was determined by microarray analysis.

Pathways analysis

Overrepresentation analysis was performed to identify biological pathways where HD exhibits the greatest influence on gene expression. The molecular and cellular functions as defined from within the IPA knowledgebase were used to determine the gene sets used for further analysis. A total of 132 gene sets, generated by combining the highest and middle-level functional categories from Ingenuity, were used for pathways analysis (Supplementary table 2). A list of the Ingenuity-annotated pathways in which each of the 55 significantly HD-modified genes (Table 1) is known to participate is provided in Supplementary table 3. Setting the threshold for significance at FDR < 0.05 for the contrast extracted from linear model results, a one-tailed Fisher’s exact test was performed to identify pathways that were greatly influenced by HD and related to HD effects on x-ray damage during co-exposure. The one-sided p values listed in Table 2 represent nominal p values that have not been adjusted for multiple testing. Note, however, that there is substantial overlap in gene sets, which would result in correlation among test results and render many common forms of adjustment as overly conservative. An overall test of altered expression among Ingenuity-defined molecular and cellular function genes (“All Ingenuity Molecular and Cellular Function Pathways”), considered in isolation of the tests for overrepresentation in specific gene subsets, produces both nominal and adjusted p = 0.0073, thus suggesting significant disruption, by HD in excess of x-ray, of important cellular and molecular systems (Supplementary figure 1). Nominal p values for the remaining gene subsets are provided for the purpose of ranking biological pathways for exploratory discovery and hypothesis generation.

TABLE 2.

Biological Pathways Influenced by HD

| Pathway number | Pathway name | Odds ratio | p Value |

| — | All Ingenuity molecular and cellular function pathways | 2.0103 | 0.0073 |

| 18 | Cell cycle/cell division process | 2.7952 | 0.0130 |

| 22 | Cell cycle/G1/S phase transition | 6.8666 | 0.0378 |

| 26 | Cell death/apoptosis | 1.9380 | 0.0527 |

| 6 | Carbohydrate metabolism/metabolic process | 3.6211 | 0.0563 |

| 17 | Cell cycle/cell cycle progression | 2.5197 | 0.0591 |

| 81 | DNA replication, recombination, and repair/metabolism | 3.3731 | 0.0664 |

| 79 | DNA replication, recombination, and repair/fragmentation | 4.7104 | 0.0725 |

| 19 | Cell cycle/cell stage | 2.3598 | 0.0731 |

| 96 | Lipid metabolism/metabolism | 3.0340 | 0.0845 |

| 78 | DNA replication, recombination, and repair/degradation | 4.0847 | 0.0920 |

| 62 | Cellular development/hypertrophy | 4.0534 | 0.0932 |

| 71 | Cellular growth and proliferation/hypertrophy | 4.0534 | 0.0932 |

| 95 | Lipid metabolism/metabolic process | 2.8567 | 0.0966 |

| 42 | Cell signaling/protein kinase cascade | 2.6618 | 0.1126 |

| 72 | Cellular growth and proliferation/proliferation | 1.6778 | 0.1163 |

| 27 | Cell death/cell death | 1.6345 | 0.1166 |

| 7 | Carbohydrate metabolism/quantity | 3.3715 | 0.1256 |

| 61 | Cellular development/growth | 3.3498 | 0.1269 |

| 97 | Lipid metabolism/modification | 3.3283 | 0.1282 |

| 58 | Cellular development/developmental disorder | 3.2862 | 0.1308 |

The 20 most overrepresented pathways are listed in Table 2. These are predominantly involved in cell cycle, cellular growth and proliferation, DNA replication, recombination and repair, cell death, and lipid and carbohydrate metabolism. Heatmaps of the gene expression values of the top three pathways demonstrate the effect of HD co-exposure across the genes within the pathways (Supplementary figures 2–4). The pathways most affected by HD are cell cycle/cell division process (Supplementary fig. 2), cell cycle/G1/S phase transition (Supplementary fig. 3), and cell death/apoptosis (Supplementary fig. 4). Within the cell cycle/cell division process pathway, the most strongly upregulated genes include IER3, EGR1 (early growth response 1), and STAT3 (signal transducer and activator of transcription 3), whereas PITX2 (paired-like homeodomain 2), XRCC4 (x-ray repair complementing defective repair in Chinese hamster cells 4), and MAP3K11 (mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase kinase 11) are among those strongly downregulated. Similar genes fall in the cell cycle/G1/S phase transition pathway, with prominently affected genes including NFKBIA (nuclear factor of kappa light polypeptide gene enhancer in B cells inhibitor, alpha), JUN (jun oncogene), CDKN1A (cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 1A), and several cyclins (CCNA1, CCND1, and CCNE1). ANGPTL4, EGR1, CTGF (connective tissue growth factor), BBC3 (Bcl2-binding component 3), and HSPB1 (heat shock 27 kDa protein 1) are among the many affected genes involved in cell death/apoptosis.

DISCUSSION

In the present study, microarray analysis was used to identify changes in gene expression underlying the pathological changes that occur when adult rats are coexposed to HD and x-ray. In our previous study, it was found that an 18-day priming exposure to the Sertoli cell toxicant HD resulted in a surprising attenuation of x-ray–induced germ cell apoptosis. Sensitization with HD exposure appears to induce an adaptive response, which alters the sensitivity of germ cells to x-rays. Using integrated bioinformatic techniques to analyze dose-response and co-exposure effects on gene expression, we identified individual genes and biological pathways underlying this attenuated germ cell response.

When studying mixed exposures, it is common practice to compare the gene expression profile after co-exposure to the gene expression profiles after exposure to the individual components of the mixture. With our study design involving multiple dose levels of each toxicant, this type of comparison could not be easily performed because of the complexity introduced by the dose-dependent effects of co-exposure. The phenotypic response of attenuated apoptosis following co-exposure was most unique; therefore, we focused primarily on the gene expression profile of the co-exposure group, dissecting the contribution of each toxicant to the co-exposure response.

HD pretreatment attenuated the downregulation by x-rays of IER3, ANGPTL4, CTGF, and ERRFI1 among other genes. IER3 is an immediate early response gene that has been shown to have an anti-apoptotic function in some cell types, promoting cell survival (Wu, 2003). ANGPTL4 is an apoptosis survival factor for endothelial cells and also plays a role in lipid metabolism and insulin sensitivity (Kim et al., 2000; Xu et al., 2005). When secreted, CTGF stimulates proliferation of various cell types and extracellular matrix component production. CTGF can also be expressed as an intracellular protein in a cell cycle–dependent manner, causing cell cycle arrest (Kubota et al., 2000). CTGF can interact with integrins on the Sertoli cell surface and may regulate essential Sertoli cell-germ cell interactions (O'Donnell et al., 2009). ERRFI1 (ERBB receptor feedback inhibitor 1) is an immediate early response gene induced during periods of cell stress and can function as a tumor suppressor (Zhang and Vande Woude, 2007). HD pretreatment also exerted a significant negative effect on many genes. In this group of genes, nearly all negative modifications by HD were an enhancement of x-ray–induced downregulation. Several of these genes (e.g., NASP, HSPB1, and ALKBH2) are involved in DNA replication, recombination and repair as well as cell death/apoptosis (e.g., GPI, CNTF, MAP3K11, COMP, and HSPB1). These changes are not surprising because x-ray exposure results in DNA damage that ultimately results in germ cell apoptosis. HD pretreatment also enhances the x-ray–induced downregulation of several genes whose products are involved in cellular growth and proliferation/cell cycle (e.g., SSRP1, NASP, GPI, PITPNM1, MAP3K11, and LOXL1) and also carbohydrate and lipid metabolism (PITPNM1, GHSR, CYGB, GPI, FBP1, ITPKA, and CNTF). Changes in carbohydrate and lipid metabolism have implications for reduced Sertoli cell support of and communication with germ cells.

Some other genes that are strongly further downregulated by HD co-exposure are LOXL1, GHSR, and PRSS21 (protease, serine, 21). GHSR and LOXL1 exhibit some of the greatest negative HD effects and recent studies have begun to reveal a role for the products of these genes in the male reproductive system. LOXL1−/− male mice exhibit decreased fertility and decreased sperm production, although the mechanisms behind these effects are unknown (Wood et al., 2009). Ghrelin is the endogenous ligand for GHSR. Locally expressed ghrelin in the testis inhibits hCG- and cAMP-stimulated testosterone secretion in vitro and also causes a reduction in steroidogenic gene expression (Lorenzi et al., 2009). PRSS21, also called TEST1 or TESTISIN, is a serine protease expressed by premeiotic primary spermatocytes in the cytoplasm and on the plasma membrane and is suggested to be involved in germ cell maturation (Hooper et al., 1999). Whereas the exact role of TEST1 is not known, it may participate in proteolytic events necessary for germ cell migration, or in the exchange of soluble factors or cell surface interactions between germ cells and Sertoli cells (Hooper et al., 1999).

In addition to focusing on individual genes altered by HD on top of x-ray, pathways analysis was used to gain a better understanding of the molecular changes underlying the co-exposure response. Biological pathways with the greatest modification of gene expression by HD exposure were identified, and within these pathways several genes of interest were revealed. A significant influence of HD on genes involved in cell cycle was discovered. Looking at the genes within these pathways below the threshold of p < 0.05, most are negatively affected by HD, suggesting that there may be cell cycle arrest. HD-mediated attenuation of genes that promote cell proliferation may cause a reduction in germ cell proliferation, rendering them more resistant to x-ray exposure. HD-exposed rats exhibited increased duration of the spermatogenic cycle that was attributed to reduced progression of 5-bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU)-labeled cells (Rosiepen et al., 1995). Compromised Sertoli cell-mediated transport of germ cells may be the cause for decreased BrdU labeling during specific stages. However, impaired division of spermatogonia may also explain the reduction in BrdU-labeled germ cells. Among the other genes within these cell cycle–related gene sets, there is an HD-mediated enhancement of CDKN1A (cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 1A, p21), a cell cycle inhibitor that is controlled by p53. p53-dependent cell cycle arrest in response to cell stress is mediated by CDKN1A/p21, and this growth arrest mediated by p21 can inhibit apoptosis (Yu and Zhang, 2005). Alternatively, there is decreased expression of several cyclins (CCNA1, CCNB1, CCNE1, CCNG1, and CCND2) and other genes involved in the promotion of cell cycle progression following co-exposure. For example, NASP (nuclear autoantigenic sperm protein [histone binding]), which is decreased by HD, is regulated by the cell cycle and functions in the transport of histones to the nucleus of dividing cells (Richardson et al., 2000).

The attenuation of germ cell apoptosis was the most remarkable histopathologic observation following co-exposure to HD and x-ray, therefore it was not surprising that the cell death/apoptosis pathway was overrepresented among significant genes. Examining the genes within this pathway, as well as considering those genes significantly altered by x-ray exposure (Supplementary table 1), there is a strong trend toward attenuation of x-ray–induced proapoptotic genes by HD co-exposure. CCNG1 (cyclin G1), BBC3 (Bcl2-binding component 3), and AEN (apoptosis-enhancing nuclease) are all proapoptotic genes that were significantly increased by x-ray exposure with HD-mediated attenuation following co-exposure. HD co-exposure prevents the induction of CCNG1 caused by x-ray. CCNG1 is a transcriptional target of p53 that regulates p53 and its functions, including apoptosis (Kimura and Nojima, 2002). Under certain cellular conditions, CCNG1 can also negatively regulate p53 and promote cell growth rather than cell cycle arrest (Chen, 2002). As discussed earlier, a decrease in germ cell proliferation, which could be related to attenuated CCNG1 upregulation, may protect germ cells from x-ray. Attenuation of x-ray–induced BBC3 and AEN was also detected by gene array analysis. BBC3, also known as PUMA (p53-upregulated modulator of apoptosis), mediates p53-induced apoptosis by either preventing the action of the antiapoptotic proteins Bcl-2 and Bcl-XL, or by promoting p53 dissociation from Bcl-XL, allowing p53 to activate Bax (Wang et al., 2007). AEN enhances apoptosis following ionizing radiation through its DNase activity (Lee et al., 2005). BBC3/PUMA and AEN are increased by 1.7- and 3.2-fold, respectively, after exposure to 5 Gy x-ray, with their expression attenuated to control levels following co-exposure. These notable differences in induction between x-ray alone and co-exposure, along with the documented roles of BBC3/PUMA and AEN in the apoptotic pathways that are activated following radiation exposure, make these genes strong candidates for further investigation. In addition to these modifications of proapoptotic genes, there was HD-dependent enhancement of antiapoptotic genes. NFKBIA (nuclear factor of kappa light polypeptide gene enhancer in B cells inhibitor, alpha), better known as IκBα, functions to inhibit nuclear factor κB (NF-κB) proteins by sequestering them in the cytoplasm in an inactive state (Jacobs and Harrison, 1998) and is enhanced by co-exposure to HD. This enhancement would be expected to reduce apoptosis as NF-κB activation is proapoptotic in the irradiated testis (Rasoulpour and Boekelheide, 2007).

In conclusion, we have derived new insights into the mechanisms underlying the phenotypic effects of HD and x-ray co-exposure by investigating global gene expression in the testis, focusing on the influence of HD on x-ray–induced gene alterations. The less supportive environment induced by HD pretreatment results in adaptation of the germ cells and an increased resistance to subsequent insults by x-ray exposure. The modulation of gene expression caused by HD sensitization corresponds well with the phenotypic characteristics resulting from HD pretreatment. Particularly, the HD-dependent attenuation of several proapoptotic genes correlates with the attenuated germ cell apoptosis. Additional studies are underway to investigate these alterations in apoptotic genes, specifically BBC3/PUMA and AEN. In the current study, gene expression analysis was performed using RNA isolated from whole testis; however, the attenuated apoptosis is stage specific (Yamasaki et al., 2010). More focused studies investigating the expression of these apoptotic genes in specific stages by qRT-PCR, which is more sensitive than microarray analysis, will provide further insight into the current findings. In addition to these alterations in apoptotic genes, HD modulated several signaling pathways of interest, including cell cycle/cell division process and cell cycle/G1/S phase transition that may mechanistically explain this reduced apoptotic response. Abnormal Sertoli cell support of germ cells and altered communication between Sertoli cells and germ cells by HD pretreatment likely contribute to the attenuation of germ cell apoptosis. This may be due to a role of Sertoli cells in regulating germ cell apoptosis following DNA damage. Alternatively, reduced Sertoli cell support may result in decreased germ cell division and therefore, reduced vulnerability to x-rays that target actively dividing cells. Future studies will explore further this possible disruption of germ cell division by HD exposure.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary data are available online at http://toxsci.oxfordjournals.org/.

FUNDING

National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences at the National Institutes of Health (P42 ES013660 and T32 ES07272).

Supplementary Material

References

- Bartosiewicz M, Penn S, Buckpitt A. Applications of gene arrays in environmental toxicology: fingerprints of gene regulation associated with cadmium chloride, benzo(a)pyrene, and trichloroethylene. Environ. Health Perspect. 2001;109:71–74. doi: 10.1289/ehp.0110971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boekelheide K. Mixed messages. Toxicol. Sci. 2007;99:1–2. [Google Scholar]

- Boekelheide K, Fleming SL, Allio T, Embree-Ku ME, Hall SJ, Johnson KJ, Kwon EJ, Patel SR, Rasoulpour RJ, Schoenfeld HA, et al. 2,5-hexanedione-induced testicular injury. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2003;43:125–147. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.43.100901.135930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter DO, Arcaro K, Spink DC. Understanding the human health effects of chemical mixtures. Environ. Health Perspect. 2002;110(Suppl. 1):25–42. doi: 10.1289/ehp.02110s125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X. Cyclin G: a regulator of the p53-Mdm2 network. Dev. Cell. 2002;2:518–519. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(02)00182-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groten JP, Feron VJ, Suhnel J. Toxicology of simple and complex mixtures. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2001;22:316–322. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(00)01720-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasegawa M, Wilson G, Russell LD, Meistrich ML. Radiation-induced cell death in the mouse testis: relationship to apoptosis. Radiat. Res. 1997;147:457–467. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hook SE, Skillman AD, Gopalan B, Small JA, Schultz IR. Gene expression profiles in rainbow trout, Onchorynchus mykiss, exposed to a simple chemical mixture. Toxicol. Sci. 2008;102:42–60. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfm293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hooper JD, Nicol DL, Dickinson JL, Eyre HJ, Scarman AL, Normyle JF, Stuttgen MA, Douglas ML, Loveland KA, Sutherland GR, et al. Testisin, a new human serine proteinase expressed by premeiotic testicular germ cells and lost in testicular germ cell tumors. Cancer Res. 1999;59:3199–3205. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs MD, Harrison SC. Structure of an IkappaBalpha/NF-kappaB complex. Cell. 1998;95:749–758. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81698-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim I, Kim HG, Kim H, Kim HH, Park SK, Uhm CS, Lee ZH, Koh GY. Hepatic expression, synthesis and secretion of a novel fibrinogen/angiopoietin-related protein that prevents endothelial-cell apoptosis. Biochem J. 2000;346(Pt 3):603–610. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura SH, Nojima H. Cyclin G1 associates with MDM2 and regulates accumulation and degradation of p53 protein. Genes Cells. 2002;7:869–880. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2443.2002.00564.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubota S, Hattori T, Shimo T, Nakanishi T, Takigawa M. Novel intracellular effects of human connective tissue growth factor expressed in Cos-7 cells. FEBS Lett. 2000;474:58–62. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(00)01573-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JH, Koh YA, Cho CK, Lee SJ, Lee YS, Bae S. Identification of a novel ionizing radiation-induced nuclease, AEN, and its functional characterization in apoptosis. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2005;337:39–47. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.08.264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorenzi T, Meli R, Marzioni D, Morroni M, Baragli A, Castellucci M, Gualillo O, Muccioli G. Ghrelin: a metabolic signal affecting the reproductive system. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2009;20:137–152. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2009.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markelewicz RJ, Jr, Hall SJ, Boekelheide K. 2,5-hexanedione and carbendazim co-exposure synergistically disrupts rat spermatogenesis despite opposing molecular effects on microtubules. Toxicol. Sci. 2004;80:92–100. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfh140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moffit JS, Bryant BH, Hall SJ, Boekelheide K. Dose-dependent effects of sertoli cell toxicants 2,5-hexanedione, carbendazim, and mono-(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate in adult rat testis. Toxicol. Pathol. 2007;35:719–727. doi: 10.1080/01926230701481931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Donnell L, Pratis K, Wagenfeld A, Gottwald U, Muller J, Leder G, McLachlan RI, Stanton PG. Transcriptional profiling of the hormone-responsive stages of spermatogenesis reveals cell-, stage-, and hormone-specific events. Endocrinology. 2009;150:5074–5084. doi: 10.1210/en.2009-0755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasoulpour RJ, Boekelheide K. NF-kappaB activation elicited by ionizing radiation is proapoptotic in testis. Biol. Reprod. 2007;76:279–285. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.106.054924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson RT, Batova IN, Widgren EE, Zheng LX, Whitfield M, Marzluff WF, O'Rand MG. Characterization of the histone H1-binding protein, NASP, as a cell cycle-regulated somatic protein. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:30378–30386. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M003781200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rockett JC, Dix DJ. Application of DNA arrays to toxicology. Environ Health Perspect. 1999;107:681–685. doi: 10.1289/ehp.99107681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosiepen G, Chapin RE, Weinbauer GF. The duration of the cycle of the seminiferous epithelium is altered by administration of 2,5-hexanedione in the adult Sprague-Dawley rat. J. Androl. 1995;16:127–135. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smyth GK. Linear models and empirical bayes methods for assessing differential expression in microarray experiments. Stat. Appl. Genet. Mol. Biol. 2004;3 doi: 10.2202/1544-6115.1027. Article3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storey JD, Tibshirani R. Statistical significance for genomewide studies. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2003;100:9440–9445. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1530509100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang P, Yu J, Zhang L. The nuclear function of p53 is required for PUMA-mediated apoptosis induced by DNA damage. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2007;104:4054–4059. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0700020104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood HM, Lee UJ, Vurbic D, Sabanegh E, Ross JH, Li T, Damaser MS. Sexual development and fertility of Loxl1-/- male mice. J. Androl. 2009;30:452–459. doi: 10.2164/jandrol.108.006122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu MX. Roles of the stress-induced gene IEX-1 in regulation of cell death and oncogenesis. Apoptosis. 2003;8:11–18. doi: 10.1023/a:1021688600370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu A, Lam MC, Chan KW, Wang Y, Zhang J, Hoo RL, Xu JY, Chen B, Chow WS, Tso AW, et al. Angiopoietin-like protein 4 decreases blood glucose and improves glucose tolerance but induces hyperlipidemia and hepatic steatosis in mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2005;102:6086–6091. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408452102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamasaki H, Sandrof MA, Boekelheide K. Suppression of radiation-induced testicular germ cell apoptosis by 2,5-hexanedione pretreatment. I. Histopathological analysis reveals stage-dependence of attenuated apoptosis. Toxicol. Sci. 2010 doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfq203. Advance Access published on July 8, 2010; doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfq203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu J, Zhang L. The transcriptional targets of p53 in apoptosis control. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2005;331:851–858. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.03.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang YW, Vande Woude GF. Mig-6, signal transduction, stress response and cancer. Cell Cycle. 2007;6:507–513. doi: 10.4161/cc.6.5.3928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.