Abstract

BACKGROUND

Recent Breakthrough Series Collaboratives have focused on improving chronic illness care, but few have included academic practices, and none have specifically targeted residency education in parallel with improving clinical care. Tools are available for assessing progress with clinical improvements, but no similar instruments have been developed for monitoring educational improvements for chronic care education.

AIM

To design a survey to assist teaching practices with identifying curricular gaps in chronic care education and monitor efforts to address those gaps.

METHODS

During a national academic chronic care collaborative, we used an iterative method to develop and pilot test a survey instrument modeled after the Assessing Chronic Illness Care (ACIC). We implemented this instrument, the ACIC-Education, in a second collaborative and assessed the relationship of survey results with reported educational measures.

PARTICIPANTS

A combined 57 self-selected teams from 37 teaching hospitals enrolled in one of two collaboratives.

ANALYSIS

We used descriptive statistics to report mean ACIC-E scores and educational measurement results, and Pearson’s test for correlation between the final ACIC-E score and reported educational measures.

RESULTS

A total of 29 teams from the national collaborative and 15 teams from the second collaborative in California completed the final ACIC-E. The instrument measured progress on all sub-scales of the Chronic Care Model. Fourteen California teams (70%) reported using two to six education measures (mean 4.3). The relationship between the final survey results and the number of educational measures reported was weak (R2 = 0.06, p = 0.376), but improved when a single outlier was removed (R2 = 0.37, p = 0.022).

CONCLUSIONS

The ACIC-E instrument proved feasible to complete. Participating teams, on average, recorded modest improvement in all areas measured by the instrument over the duration of the collaboratives. The relationship between the final ACIC-E score and the number of educational measures was weak. Further research on its utility and validity is required.

KEY WORDS: chronic care, ambulatory care, graduate medical education, assessment, quality improvement

BACKGROUND

Calls for improvement in health care for patients with chronic illnesses abound1–5. Over the past decade, multiple improvement collaboratives have addressed the care gap in diverse practice settings6,7, but less is known about efforts to improve chronic illness care in academic practices where future physicians train8–10.

In 2005, the Institute for Improving Clinical Care of the Association of American Medical Colleges launched a national breakthrough series collaborative designed to train health care teams that included residents in training to improve the quality of care for patients with chronic illnesses. The collaborative used the Chronic Care Model (CCM) to structure targets for improvement (Table 1)11. Teaching hospitals with affiliated primary care residency training programs (internal medicine, family medicine, or pediatrics) were invited to participate. Participation required the formation of inter-professional teams, which included residents training in primary care disciplines, who would dedicate efforts to re-designing their academic practice sites to improve both clinical care delivery and the educational program.

Table 1.

Chronic Care Model Components

| GOAL: Productive interactions between activated patients and a prepared practice team lead to improved care that is safe, effective, timely, patient-centered, efficient, and equitable11 |

| Model elements and examples related to the larger health system |

| Health system component |

| • Visible support from organization’s leadership |

| • Incentives aligned with improved quality of chronic care delivery |

| Community resources component |

| • Linking patients and their families/caregivers to effective community programs |

| Model elements and examples related to the clinical practice level |

| Delivery system design component |

| • Team members have defined roles and tasks |

| • Planned visits are used to deliver evidence-based care |

| • Teams provide follow-up and care management |

| Decision support component |

| • Evidence-based guidelines are embedded in daily practice |

| • Specialist expertise is integrated into team care |

| • Guidelines and goals of care are shared with patients |

| Clinical Information Systems component |

| • Timely clinical reminders are built into the system |

| • Population data are used to monitor delivery system re-design |

| • Tracking of individual patients supports care planning |

| Self-management support component |

| • The patient’s role is central to managing the health condition |

| • Strategies to support patients' self-efficacy are integrated into care |

| • Patients are linked to community resources to provide ongoing support in meeting individual goals |

In breakthrough series collaboratives12, participating organizations commit to implementation of improvement strategies over a period of several months, alternating between ‘learning sessions’ where teams from participating organizations come together to learn about the chosen topic and to plan changes (e.g., optimizing care for chronic illnesses), and subsequent ‘action periods’ in which teams return to their organizations and test those changes in clinical settings. Most recently, this process has been applied to coordinate and accelerate efforts to improve chronic illness care. Multiple previous collaboratives have focused efforts on improving chronic illness care13, but few have included residency training practices in these efforts, and none have specifically addressed improving residency education in parallel with improving the delivery of clinical care.

Many teams participating in collaboratives use the Assessment of Chronic Illness Care (ACIC)14,15, an instrument developed and validated to identify deficiencies in their systems of care for chronic conditions and direct improvement efforts to address those gaps8. The ACIC survey is typically self-administered three times as a team-based group exercise: at the start, a midpoint, and the end of the collaborative. Scores are expected to improve as changes in the practice environment are implemented.

As work to improve chronic illness care moves to residency training sites, residency programs also need tools to help multidisciplinary, clinical teams identify gaps in their educational programs and to assist with continuous improvement in chronic illness care education. As part of the national chronic care collaborative, we developed and pilot-tested an educational survey modeled after the ACIC. Subsequently, the California Healthcare Foundation funded a chronic care collaborative in California teaching hospitals, which provided the opportunity to further test this instrument. We report here on the development and preliminary results of the Assessment of Chronic Illness Care Education or ACIC-E.

Our aim was to develop a survey that could help residency education programs and teaching practices identify curricular gaps in chronic care education and design efforts to address those gaps. As such, the survey is a needs assessment tool that can be used to identify and periodically monitor improvement efforts. Similar to the ACIC, the ACIC-E survey is self-administered as a team-based exercise in practices where residents provided care to patients with chronic illnesses applying the chronic care model. We hypothesized that teams’ self-rated scores on the ACIC-E would increase over time as they focused on improving their educational programs.

METHOD

Setting

Thirty-six self-selected quality improvement teams from 22 institutions participated in the national collaborative. Twenty-one self-selected teams from 15 institutions participated in the subsequent California collaborative; two teams from one institution combined for a final cohort of 20 teams. Individual teams generally consisted of a clinical practice champion, such as the medical director of the training practice, an education leader, such as the residency program director, residents in training at the practice site, and nurses, social workers, receptionists, medical assistants, and/or pharmacists from the practice. Most members of these teams attended the learning sessions to learn, plan changes, and assess progress. Team members in attendance at the learning sessions completed the ACIC-E survey as described below.

ACIC-E Development

As the leadership group for the national collaborative, we reviewed the constructs of the ACIC instrument and discussed parallel constructs for process improvement in education. We developed performance statements related to the six components of the Chronic Care Model: organization of health care (four statements), community linkages (three), self-management support (five), delivery system design (six), decision support (four), and clinical information systems (five). Four anchors describing graduated levels of performance from “little or none” to “fully implemented” were developed to represent various stages of improving educational efforts related to chronic illness care. Examples from the ACIC instrument and parallel constructs from the ACIC-E are shown in Table 2. Some constructs were directly translated from the ACIC to apply to educational settings. Others were developed to address unique educational challenges. As with the ACIC instrument, we used a 12-point numerical scale (0 to 11) for teams’ self-scoring. The higher point values indicated that the actions described in the anchors were more fully implemented. The instrument was designed to be completed as a team discussion exercise and take no more than 30 min to complete.

Table 2.

Examples from Assessing Chronic Illness Care (ACIC)14,15 and Assessing Chronic Illness Care Education (ACIC-E) Surveys (Appendix)

| ACIC survey | ACIC-E survey |

|---|---|

| ORGANIZATION OF HEALTHCARE DELIVERY SYSTEM | |

| Overall Organizational Leadership in Chronic Illness Care…does not exist or there is a little interest…is part of the system’s long-term planning strategy, receives necessary resources, and specific people are held accountable | Overalleducationleadership in chronic illness care…does not exist or there is a little interest (lowest anchor)…is reflected in the institution’s educational priorities, receives necessary resources, and specific training program leader(s) are held accountable for chronic care education (highest anchor) |

| COMMUNITY LINKAGES | |

| Linking patients to outside resources…is not done systematically…is accomplished through active coordination between the health system, community service agencies, and patients | Learner assessment of patients’ community-based activities…relies upon patients or families bringing the concern or activity to the learner’s attention (lowest) to…is routinely accomplished by the care team as a task delegated to the most appropriate team member with follow-up to provide resources as needed to patients, and includes dedicated teaching activities to support learners in integrating these patient assessments in care planning (highest) |

| SELF-MANAGEMENT SUPPORT | |

| Self-management support…is limited to the distribution of information (pamphlets, booklets)…is provided by clinical educators affiliated with each practice, trained in patient empowerment and problem-solving methodologies, and see most patients with chronic illness | Self-management support strategies…are limited to the distribution of patient information (lowest) to…are provided by clinic staff affiliated with each practice, trained in patient empowerment and problem-solving methodologies, and systematically include learners in delivering this care (highest) |

| DECISION SUPPORT | |

| Provider education for chronic illness care…is provided sporadically…includes training all practice teams in chronic illness care methods such as population-based management and self-management support | Self-directed learning…is expected but initiated entirely by the learner without faculty guidance (lowest) to…is expected for all learners and includes structured teaching session on critical appraisal of the medical literature to address questions about chronic disease management, application of learning to questions arising in practice, learner-centered teaching sessions to report findings, and faculty role modeling of these behaviors (highest) |

| DELIVERY SYSTEM DESIGN | |

| Planned visits for chronic illness care…are not used…are used for all patients and include regular assessment, preventive interventions, and attention to self-management support | Planned visits for chronic illness care in the learners’ practice…are not used (lowest) to…are used for all patients inthe target population and include regular assessment, preventive interventions, and attention to self-management support with learners as integral members of the planned visit practice team (highest) |

| CLINICAL INFORMATION SYSTEM | |

| Registry (list of patients with specific conditions)…is not available…is tied to guidelines that provide prompts and reminders about needed services | Registry (list of patients with specific conditions) for practice…is not available…is tied to guidelines that provide prompts and reminders about needed services and regular performance reports to learners including discussion and reflection on disease management |

An initial instrument was drafted, discussed among the leadership group, and edits incorporated. We repeated this process until consensus was reached. The instrument was then pilot tested with one team enrolled in the national collaborative, resulting in further refinement to clarify directions and concepts, and improve the rating scale descriptors.

ACIC-E Pilot Testing

In 2005, the ACIC-E was mailed electronically to the education representative for each team enrolled in the national collaborative. Reminders were sent to maximize response. At the second learning session of the national collaborative, each team worked in small groups with other teams and a leadership group facilitator. Each team presented their own completed ACIC-E report and explained their self-ratings. Teams revised their self-reported ratings as necessary based on the group discussion. Not infrequently, their ratings were readjusted downwardly. This normative calibration process was designed to provide at least one external monitor of the self-reported results as well as to improve shared understanding of the statements and rating scale. Revised surveys were collected and recorded as baseline team assessments. We asked teams to complete the instrument two more times, at mid-point and at the end of the collaborative, using the same group discussion method described. We encouraged feedback about statements that were unclear. Minor edits were made to the survey to improve readability.

ACIC-E Implementation

In 2007, we implemented the ACIC-E instrument at the beginning of the California collaborative and collected baseline, mid-point, and end-of-collaborative self-ratings using the same process. In addition to completing the ACIC-E instrument, California teams were encouraged to improve their educational programs to better align residency curricula with their efforts to improve the delivery of chronic illness care, using educational measures developed and pilot tested in the national collaborative to monitor these educational improvements16. These educational measures, shown in Table 3, were designed for residency programs to have a simple way of knowing if a change in the curriculum resulted in improved resident exposure to, or performance of, learning objectives. Teams were asked to report monthly on the two required measures and as many optional measures as they desired, essentially building their own unique sets of education performance metrics.

Table 3.

California Collaborative Teams’ Use of Education Measures

| Educational measures | Number of teams reporting (N, %) |

|---|---|

| REQUIRED | |

| Number of residents receiving, reviewing, and discussing at least one registry report for the practice population | 14 (70%) |

| Number of residents learning (and demonstrating) self-management support strategies | 14 (70%) |

| OPTIONAL | |

| Number of residents participating in health system teaching sessions | |

| Number of residents participating in teaching sessions that address registry creation, validation, and interpretation | |

| Number of residents analyzing the practice report and outlining an evidence-based improvement recommendation (e.g., portfolio entry) | |

| Number of residents participating in a PDSA9 cycle to test a change for the condition of interest | 8 (40%) |

| Number of residents actively participating on a practice improvement (QI) team over total residents in target learning population | 6 (30%) |

| Number of patients completing a P-ACIC10 in the target patient population | |

| Number of residents receiving the results summary of the P-ACIC | 5 (25%) |

| Number of residents with satisfactory completion of a Self-Management mini-CEX | |

| Number of residents setting self-directed learning action plans | |

| Number of residents completing their action plans, including teaching their colleagues how to use evidence to improve chronic disease management | |

| Number of residents reviewing scientific evidence and development process behind guidelines used in the practice | |

| Number of residents appraising the literature for clinical care guidelines and sharing findings with team members | |

| Number of residents identifying and answering a clinical question that arises in the delivery of care to the population of interest (and teaching others what was learned) | 5 (25%) |

| Number of residents documenting assessment of patients’ use of community-based support programs | |

| Number of residents identifying relevant community resources that meet an important need arising in the delivery of care to the population of interest, adding resources to repository, and teaching others what was learned | |

| Number of residents participating in a planned visit for the condition of interest (measure developed by the California collaborative teams) | 11 (55%) |

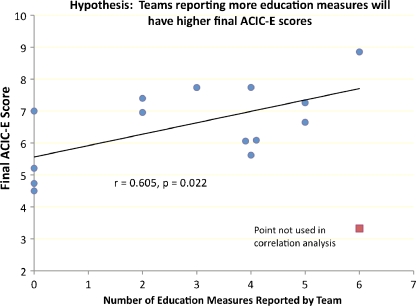

We hypothesized that the number of educational measures utilized and reported would be indicative of the level of a team’s engagement in educational improvement with more measures suggesting a more advanced stage of curricular integration of education with chronic care practice re-design. In contrast, teams facing significant barriers to chronic care practice re-design and curricular reform would make fewer changes in their curriculum and would have fewer measures to report. Since the ACIC-E was designed to assess the level of improvement of chronic care education, we hypothesized that teams with higher final ACIC-E scores would show evidence of more curricular change as reflected in more robust sets of education performance metrics.

Analysis

Mean ACIC-E scores at baseline, midpoint, and endpoint were calculated for the survey overall and for each component for both collaboratives. For the implementation collaborative (California), the numbers of team-specific monthly education reports were totaled, and the numbers of different education measures utilized by teams were counted. Teams were considered to have reported on a specific measure if they provided at least six monthly reports. The final team-specific ACIC-E scores were compared with the number of different educational measures utilized. All teams completing the final ACIC-E were included in the comparison. Pearson correlations were calculated for this comparison.

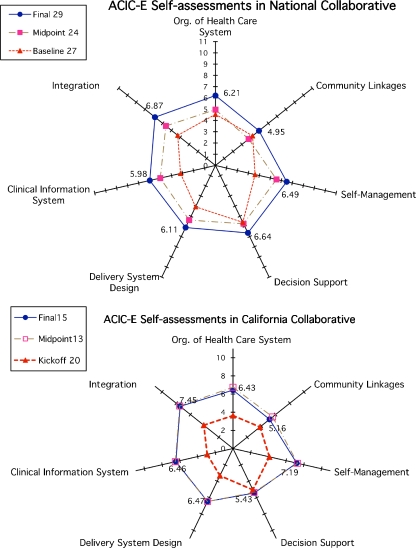

RESULTS

A total of 29 teams from the national collaborative and 15 teams from the California collaborative completed the final ACIC-E. For the California collaborative, 11 of 20 participating teams completed the survey at all three points in time (55%), 4 teams (20%) completed two surveys, and 5 teams (25%) completed only one survey (Fig. 1). Mean scores for each sub-scale chronic care component and the integration components of the ACIC-E for both collaboratives are shown in Figure 2. In all areas, teams reported moderate progress in implementing educational changes to improve chronic illness care. For both collaboratives, the lowest baseline performance rating overall was the use of clinical information systems to teach and improve chronic care, but attention to this gap resulted in the greatest improvement over time. In contrast, the highest baseline rating was in decision support, the use of evidence-based medicine to teach and support clinical care decisions, and practice guideline utilization, yet this area showed little improvement over time.

Figure 1.

Distribution of mean Assessment of Chronic Illness Care Education (ACIC-E) self-assessment scores for California Collaborative teams at kickoff, mid-point, and final survey time points.

Figure 2.

Collaborative teams’ self-assessment using the Assessment of Chronic Illness Care Education (ACIC-E)*. *Legend indicates number of teams completing the instrument at three points during the collaborative. Data points are mean scores for each sub-component of the ACIC-E for all reporting teams. For the national collaborative, the first assessment was done at the second learning session (“baseline”); for the California collaborative, the first assessment was done at the initial meeting called the “Kickoff” session.

The California collaborative teams’ use of education measures is shown in Table 3. Fourteen teams (70%) reported monthly results for the required education measures on use of registries and self-management support. In addition, a subset of teams utilized education measures for monitoring participation in planned visits, answering clinical questions and teaching others, assessing patients’ perceptions of chronic illness care in the practice, participation in improvement work, and inclusion on quality improvement teams (mean 4.3 measures per team).

Of the 15 California collaborative teams that completed the final ACIC-E, 11 reported from 2 to 6 different education measures (mean 2.44). Three other teams reported a mean of 5 measures, but could not be included in the correlation analysis because they did not complete the final ACIC-E survey. Two teams completed neither reports nor the final survey. The relationship between the final ACIC-E summary score and the number of educational measures the 15 teams reported was weak when all teams were included (R2 = 0.06, p = 0.376). A single team reported a high number of educational measures, but self-rated poorly on the instrument (six measures, summary score 3.32). When this team was removed from the analysis, the probability of correlation improved (R2 = 0.37, p = 0.022) (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Relationship between final ACIC-E self-assessment score and number of educational measures reported for 15 California collaborative teams.

DISCUSSION

This report describes our efforts to develop a self-rating instrument to assist teams with identifying and directing improvement efforts in their residency educational programs for chronic care. The instrument proved feasible to complete, and participating teams, on average, recorded improvement in almost all areas measured by the tool over the duration of the collaborative. Greatest improvement was seen in novel areas for traditional training programs such as using population disease registries to monitor the quality of care delivered or including patient self-management as a core component of health care delivery. As expected, most residency programs routinely use multiple methods to teach and reinforce use of evidence-based decision-making. Less progress was noted in this area.

In the California collaborative, little improvement was noted between the mid-point and final ACIC-E self-assessments. Because of prior health care improvement efforts in the state, several of these teams were more prepared to initiate improvement at the start of the collaborative and probably realized more easily obtained changes by the mid-point of the collaborative. In contrast, the national collaborative included teams from across the US with considerable variation in readiness for change. Progress was more incremental for these teams.

Over the 18-month time period of the collaborative, programs improved self-ratings to the mid-range of the ACIC-E 12-point scale for all components, leaving plenty of room for continual curricular monitoring and improvement. Further study is required to determine if the ACIC-E components represent valuable educational aims, if the changes in scores we observed represent educationally meaningful change, and if reaching scores in the highest range is related to superior quality of chronic illness care education.

The ACIC-E instrument uses generic language in reference to ‘learners.’ Although the purpose of the collaboratives was to facilitate educational change in primary care residency training programs where the targeted learners are residents, it can be used and studied in other health professions' training settings aiming to improve chronic illness care education.

The relationship between the final ACIC-E scores and the number of educational measures that teams from the California collaborative chose to report was weak and improved when a single outlier was removed from the analysis. This outlier completed two of three ACIC-E surveys with little change in low self-ratings (Fig. 3, Team F) yet reported the highest number of education measures (six) used by any team. This finding is unexplained. Future research should include qualitative investigation of such outliers to better understand how teams are interpreting both the ACIC-E and the education measures.

Our findings may be the result of the small number of participating teams, the relatively short observation period, teams’ varying interpretation of the anchors on the ACIC-E components, or teams lack of attention to optional reporting of educational measures. Although the educational measures were developed in direct relationship to the goal of developing, implementing, and improving curricula using the chronic care model, the ACIC-E instrument self-ratings may be more related to barriers in the educational environment than to specific curricular design elements targeted by the educational measures. Further, the educational measures themselves may not be a valid reflection of educational improvement efforts.

Our study has several limitations. First, we relied on self-report and teams likely interpreted their performances differently. We attempted to minimize these differences through referent setting group discussion of each result at every collaborative meeting. It is possible that team members did not reach consensus in determining their survey responses, allowing more assertive team members to dominate decisions. Since teamwork is a vital component for improving chronic care and working in collaboratives, we purposefully chose the team approach for completing surveys. Use of the ACIC-E was just as much an intervention (engaging teams in setting priorities and working on specific changes) as a measurement tool. The consensus discussion was essential for getting all team members onboard for working on changes to their education programs. Second, not all teams completed all three ACIC-E surveys. The results may represent what is possible in more highly functioning teams rather than a true average of participating teams. Third, we had a small sample of teams in the California collaborative for testing the relationship between the instrument and reported educational measures. A larger sample may yield different results.

Further research on the usefulness of the ACIC-E as a tool that can assist improvement teams and educational programs in identifying chronic care curricular gaps and monitor improvement efforts to address those gaps is needed.

Acknowledgement

The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and the California Healthcare Foundation generously supported the academic chronic care collaboratives that served as the basis for this work.

Conflict of Interest None disclosed.

APPENDIX

![]()

References

- 1.Crossing the Quality Chasm: a New Health System for the Twenty-first Century. Washington: National Academy Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stevens DP, Wagner EH. Transforming residency training in chronic illness care—now. Acad Med. 2006;81:685–687. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200608000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jackson GL, Weinberger M. A decade with the chronic care model: some progress and opportunity for more. Med Care. 2009;47:929–931. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181b63537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bodenheimer T, Chen E, Bennett H. Confronting the growing burden of chronic disease: can the US health care workforce do the job? Health Aff. 2009;28:64–74. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.28.1.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Foote SM. Next steps: how can Medicare accelerate the pace of improving chronic care? Health Aff. 2009;28:99–102. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.28.1.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chin MH, Drum ML, Guillen M, et al. Improving and sustaining diabetes care in community health centers with the disparities collaboratives. Med Care. 2007;45:1135–1143. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31812da80e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wagner EH, Austin BT, Korff M. Organizing care for patients with chronic illness. Milbank Q. 1996;74:511–544. doi: 10.2307/3350391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Landis SE, Schwarz M, Curran DR. North Carolina family medicine residency programs’ diabetes learning collaborative. Fam Med. 2006;38:190–195. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Warm EJ, Schauer DP, Diers T, et al. The ambulatory long-block: an Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) Educational Innovations Project (EIP) J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23:921–926. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0588-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dipiero A, Dorr DA, Kelso C, Bowen JL. Integrating systematic chronic care for diabetes into an academic general internal medicine resident-faculty practice. JGIM. 2008;23:1749–1756. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0751-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wagner EH, Austin BT, Davis C, Hindmarsh M, Schaefer J, Bonomi A. Improving chronic illness care: translating evidence into action. Health Aff. 2001;20:64–78. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.20.6.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Institute for Healthcare Improvement. The Breakthrough Series: IHI’s Collaborative Model for Achieving Breakthrough Improvement. 2003.

- 13.Coleman K, Austin BT, Brach C, Wagner WH. Evidence on the chronic care model in the new millennium. Health Aff. 2009;28:75–85. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.28.1.75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bonomi AE, Wagner EH, Glasgow RE, VonKorff M. Assesment of Chronic Illness Care (ACIC): a practical tool to measure quality improvement. Health Serv Res. 2002;37:791–820. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.00049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.http://improvingchroniccare.org/index.php?p=Survey_Instruments&s=165 (ACIC 3.5, accessed March 23, 2010)

- 16.Bowen JL, Stevens DP, Sixta CS, et al. Developing measures of educational change for collaborative teams implementing the Chronic Care Model in teaching practices. JGIM 2010; doi:10.1007/s11606-010-1358-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]