ABSTRACT

Clinician educators—who work at the intersection of patient care and resident education—are well positioned to respond to calls for better, safer patient care and resident education. Explicit lessons that address implementing health care improvement and associated residency training came out of the Academic Chronic Care Collaboratives and include the importance of: (1) redesigning the clinical practice as a core component of the residency curriculum; (2) exploiting the efficiencies of the practice team; (3) replacing “faculty development” with “everyone’s a learner;” (4) linking faculty across learning communities to build expertise; and (5) using rigorous methodology to design and evaluate interventions for practice redesign. There has been progress in addressing three thorny academic faculty issues—professional satisfaction, promotion and publication. For example, consensus criteria have been proposed for both faculty promotion as well as the institutional settings that nurture academic health care improvement careers, and the SQUIRE Publication Guidelines have been developed as a general framework for scholarly improvement publications. Extensive curricular resources exist for developing the expert faculty cadre. Curricula from representative training programs include quantitative and qualitative research methods, statistical methodologies appropriate for measuring systems change, organizational culture, management, leadership and scholarly writing for the improvement literature. Clinician educators—particularly those in general internal medicine—bear the principal responsibility for both patient care and resident training in academic departments of internal medicine. The intersection of these activities presents a unique opportunity for their playing a central role in implementing health care improvement and associated residency training. However, this role in academic settings will require an unambiguous development strategy both for faculty and their institutions.

Key words: clinician educators, patient care, physician training

LONG-STANDING CALLS FOR BETTER, SAFER PATIENT CARE AND PHYSICIAN TRAINING

More than a decade has passed since reports from the Institute of Medicine outlined paths to better and safer care1,2 as well as associated goals for health professions training.3 Moreover, a 2004 Society of General Internal Medicine Report on the Future of General Internal Medicine4 called for general internists to adopt and disseminate knowledge for better, safer patient care through adoption of the principles of continuous health care quality improvement, application of information technology, and effective clinical practice in teams.

Clinician educators are uniquely positioned to answer these calls because they serve at the nexus of patient care and medical education. On the other hand, their current portfolio of clinical and academic obligations is daunting even without the prospect of an additional expectation to be academic leaders of health care improvement.

FIVE LESSONS ON IMPLEMENTING HEALTH CARE IMPROVEMENT IN ACADEMIC SETTINGS

Findings from the 41 teams that successfully participated in the Academic Chronic Care Collaboratives (ACCC) offer examples of effective strategies for implementing health care improvement in academic settings.5 Clinician educators were most frequently the leaders of these teams that redesigned their resident practices. They faced similar challenges—limited budgets, high demands for clinical and teaching obligations, and the need to maintain career momentum. Five steps emerged from their experiences that offer lessons for consideration by others.

-

First, redesign the practice. The clinical practice itself provides a core component of both the formal and informal residency curricula.5 The teams that introduced the Chronic Care Model into their residency practices found that transforming the practice generally had to be completed before they could proceed to address formal curricular changes.5,6 Examples of such practice redesign included implementation of electronic systems (registries) to track and provide patient outcomes feedback to clinicians,7 introduction of group visits8 and patient scheduling that anticipated rather than reacted to patient needs.9

An early salutary discovery was that the ambulatory practice offered clinician educators a more manageable context for practice redesign than the inpatient setting. While still a daunting task, the faculty leader could more readily get his/her arms around the many organizational issues, for example, team-building, scheduling, records, etc.,8–10 compared to similar efforts in the more complicated inpatient environment that generally entails the overlapping stakeholder interests of the many clinical departments and hospital administrative domains.

The biggest dividend in addressing the clinical practice setting first is that residents ultimately can practice freed from many of the burdensome legacy systems that constantly require clinicians’ use of redundant work-arounds to achieve good care.9

Exploit the efficiencies of a team approach to change the care setting. While clinician educators generally led the ACCC teams, the task of transforming a resident practice is too great—and the process too complex—for any one “champion” to accomplish alone.11 Transforming the practice requires effective mustering of practice staff—faculty, residents, nurses and managerial staff—with the requisite diverse skills and knowledge to incorporate continuous improvement into patient care and education. And it particularly requires the investment of residents in the clinical care setting5—extending their role well beyond individual QI “projects” to include full ownership of the clinical outcomes.

Replace “faculty development before teaching the residents” with “everyone is a learner.” Eliminating wasteful processes—a basic principle of health care improvement—can also be applied to faculty development. The ACCC teams quickly recognized that all participants—faculty as well as residents—generally started at the same place when learning new techniques for improving care. In contrast to a more traditional, sequential approach of training faculty first, then presenting the curriculum to residents, all participants assumed the role of “learner” in the ACCC.5,6 This strategy builds teamwork into the improvement work, creates an opportunity for faculty to model continuous learning and improvement, and is the most rapid method for bringing the results of improved care processes to the patient.

-

Develop high levels of improvement expertise. Many institutions that are in the initial stages of building faculty for the scholarship of health care improvement may lack local expertise and professional role models. These shortfalls can be overcome by taking advantage of resources available via the Internet, through learning collaboratives, and by participation in professional organizations that are committed to improving patient care. National collaboratives like the ACCC,5,7,12 and organizations such as the Academy for Healthcare Improvement,13 Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality,14 Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education15 and Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI),16 provide opportunities for widened professional associations outside a single institution.

Nevertheless, an established expert faculty cadre is as integral to health care improvement as it is for success in health services research, clinical epidemiology and other scholarly fields within general internal medicine. This expertise includes knowledge of quantitative and qualitative research methods, statistical methods for measurement of patient care and systems change—such as statistical process control—organizational culture, management, formal study of leadership and writing for the scholarly improvement literature.

Role models for successful academic careers in health care improvement and education can be found in the institutions that offer training programs in these fields. Examples include the VA National Quality Scholars Program,17–20 the IHI Fellowship Program,21 graduate level programs such as those offered by the Dartmouth Institute for Health Policy and Clinical Practice,22 and newly emerging residencies like the Leadership and Preventive Medicine Residency at Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center.23 Students and fellows in these programs generally work with faculty role models to design and implement major organizational improvement initiatives as part of advanced research required for successfully completing the program.

Use rigorous methodology to implement and evaluate interventions for practice redesign. Clinician educators in the ACCC who were more successful in redesign of practice sites and curricula were often the beneficiaries of senior colleagues in their institutions who offered mentorship in rigorous evaluation and publication. Frequently these senior mentors drew on successful careers in health services research for such guidance. In addition, successful mentoring frequently requires distance techniques for added efficiencies.24 To develop skills in critical analysis of redesign efforts, these ACCC site leaders took advantage of participation across sites using the collaborative model5,7,24 as well as local faculty mentoring.25

PROMISING NEWS ON THREE POTENTIALLY THORNY ISSUES: PROFESSIONAL SATISFACTION, PROMOTION AND PUBLICATION

The prospect of this emerging leadership role comes freighted with three potentially thorny issues: the negative impact of additional faculty burdens on professional satisfaction, the challenge of convincing promotions committees of its academic merit and the task of publication in a field that embodies new epistemologies—new ways of knowing. Fortunately there is promising news on all three fronts.

Professional satisfaction Professional satisfaction for clinician educators can vary in different institutions and is generally related to academic work conditions that are unique to their practice setting and academic institution. Johnson et al. conducted extensive ethnographic studies of the ACCC teams as the Academic Collaboratives progressed. Of interest, they have reported a prominent theme of work satisfaction or “joy in work” among those teams that were relatively more successful in the redesign of their patient care settings and resident education.26 While these are preliminary findings, the results of these qualitative studies suggest that enhanced work satisfaction may be a salutary professional outcome of participation in successful academic health care improvement.

Academic promotion If clinician educators are to have confidence in the potential rewards for valid scholarly work in health care improvement, consistent promotion criteria on a par with other faculty must be part of the culture and governance of their academic health centers.27 Selection criteria for participation in the ACCC included demonstration of a commitment by leadership to health care improvement as an institutional priority.5

Examples of similarly committed academic health centers can also be found among the 16 participating institutions in the earlier IHI Health Professions Education Collaborative (HPEC),28 5 of which also participated in the ACCC. This earlier collaborative was initiated to develop strategies for implementation of the AAMC Medical Schools Objectives Project Quality of Care Report.29

Model promotion criteria were developed in 2005 by HPEC faculty and senior leaders to serve as examples for promotions committees in institutions that sought to build a scholarly health care improvement faculty. They used a Delphi process that set a high bar and included expectations for funding, publication and scholarly reputation. Their previously unreported results are shown in Text box 1.

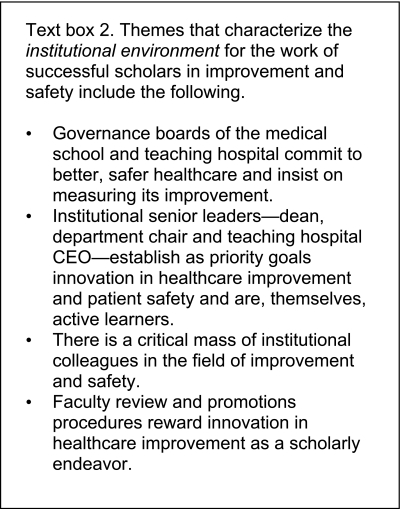

The HPEC employed a similar process to describe institutional criteria for medical centers where such successful academic careers could readily develop. These 16 institutions were themselves examples of such institutions and examined their own culture and academic environments to develop this short list (Text box 2). The overall list that emerged emphasizes again the importance of like-minded faculty peers and unequivocal institutional leadership.

Successful scholarly publication The strongest predictor—and perhaps the biggest hurdle—for promotion of clinician educators from assistant professor to associate professor is the number of published first-author peer-reviewed papers.27 The clinician educator who seeks to publish his/her original health care improvement work can find it a particularly daunting challenge because editors and reviewers frequently measure their submitted work by a yardstick designed for the randomized controlled trial.30 However, guidelines have been developed that offer a general framework for scholarly improvement publications—the SQUIRE Publication Guidelines (Standards for Quality Improvement Reporting Excellence).30 Adoption of SQUIRE by a growing number of journals—including the Journal of General Internal Medicine and Annals of Internal Medicine—may provide a useful opportunity for scholars who seek to publish outcomes of original quality improvement research.30–32

Finally, publication of reports that describe innovative residency curricula in quality improvement33 offers an additional opportunity for Clinician Educators.34–36 Moreover, the growing number of online sites that disseminate examples of such education innovation offer clinician educators additional opportunities for publication.13–16

CONCLUSION

There is a growing view that integrating health care improvement into patient care and resident training requires every health care professional to undertake continuous improvement for themselves, their care teams and their health systems.37 The role for clinician educators as leaders of such change offers opportunities for rewarding academic careers. Even more importantly, the benefits that can be realized—by health systems, faculty, residents, patients and society—goes a long way toward providing a significant response to society’s and the profession’s call for a defined path to better, safer care.1–4

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS AND FUNDING SOURCES

The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and the California HealthCare Foundation supported the Academic Chronic Care Collaboratives on which many of the conclusions for this Perspective were based.

Conflict of Interest None disclosed.

References

- 1.To err is human: Building a safer health system. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 1999. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Crossing the quality chasm: A new health system for the 21st century. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Health professions education: A bridge to quality. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Larson EB, Fihn ST, Kirk LM, Levinson W, Loge RV, Reynolds E, Sandy L, Schroeder S, Wenger N, Williams M. The future of general internal medicine: Report and recommendations from the Society of General Internal Medicine (SGIM) Task Force on the Domain of General Internal Medicine. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19:69–77. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2004.31337.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stevens DP, Bowen JL, Johnson JK, Woods DM, Provost LP, Holman HR, Sixta CS, Wagner EH. A multi-institutional quality improvement initiative to transform education for chronic illness care in resident continuity practices. J Gen Intern Med. 2010; 25:XX. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Bowen JL, Stevens DP, Sixta CS, Provost L, Johnson JK, Woods DM, Wagner EH. Developing measures of educational change for collaborative teams implementing the Chronic Care Model in teaching practices. J Gen Intern Med. 2010; 25:XX. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Toolkit for implementing the chronic care model in academic settings.http://www.ahrq.gov//populations/chroniccaremodel/. Accessed June 3, 2010.

- 8.Kirsh S, Watts S, Pascuzzi K, O’Day ME, Davidson D, Strauss G, Kern EO, Aron DC. Shared medical appointments based on the chronic care model: a quality improvement project to address the challenges of patients with diabetes with high cardiovascular risk. Qual Saf Health Care. 2007;16:349–353. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2006.019158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Warm EJ, Schauer DP, Diers T, Mathis BR, Neirouz Y, Boex JR, Rouan G. The ambulatory long-block: an Accreditation for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) Educational Innovations Project (EIP) J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23:921–926. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0588-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Warm EJ. Interval examination: the ambulatory long block. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25:750–752. doi: 10.1007/s11606-010-1362-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Damschroder LJ, Banaszak-Holl J, Kowalski CP, Forman J, Saint S, Krein SL. The role of the “champion” in infection prevention: results from a multisite qualitative study. Qual Saf Health Care. 2009;18:434–440. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2009.034199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Improving Chronic Illness Care Resources. http://www.improvingchroniccare.org/index.php?p=Resource_Library&s=159. Accessed June 3, 2010.

- 13.Academy for Healthcare Improvement Homepage. http://www.a4hi.org/. Accessed June 3, 2010.

- 14.AHRQ Health Care Innovations Exchange. Innovations and Tools to improve Quality and Reduce Disparities. http://www.innovations.ahrq.gov/qualitytools/listall.aspx. Accessed June 3, 2010.

- 15.ACGME Outcome Project. Enhancing residency education through outcomes assessment. http://www.acgme.org/outcome/. Accessed June 3, 2010.

- 16.IHI Open School for Health Professions. http://www.ihi.org/IHI/Programs/IHIOpenSchool/. Accessed June 3, 2010.

- 17.Batalden PB, Stevens DP, Kizer KW. Knowledge for improvement: Who will lead the learning? Qual Manag Health Care. 2002;10:3–9. doi: 10.1097/00019514-200210030-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Splaine ME, Aron DC, Dittus RS, Kiefe CI, Landefeld CS, Rosenthal GE, Weeks WB, Batalden PB. A curriculum for training quality scholars to improve health and health care of veterans and the community at large. Qual Manag Health Care. 2002;10:10–18. doi: 10.1097/00019514-200210030-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Splaine ME, Ogrinc G, Gilman SC, Aaron DC, Estrada CA, Rosenthal GE, Lee S, Dittus RS, Batalden PB. The Department of Veterans Affairs National Quality Scholars Fellowship Program: experience from 10 years of training Quality Scholars. Acad Med. 2009;84:1741–1748. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181bfdcef. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.VA Quality Scholars Fellowship. http://www.vaqs.org/. Accessed June 3, 2010.

- 21.Fellowship Programs at the Institute for Healthcare Improvement. http://www.ihi.org/IHI/Programs/ProfessionalDevelopment/FellowshipPrograms.htm. Accessed June 3, 2010.

- 22.The Dartmouth Institute for Health Policy and Clinical Practice. Center for Education. http://tdi.dartmouth.edu/centers/education/degrees/ms/course-listings/. Accessed June 3, 2010.

- 23.Dartmouth-Hitchcock GME Programs. Leadership and Preventive Medicine Residency. http://gme.dartmouth-hitchcock.org/leadership.html. Accessed June 3, 2010.

- 24.Luckhaupt SE, Chin MH, Mangione CM, Phillips RS, Bell D, Leonard AC. Tsevat. Mentorship in academic general internal medicine. Results of a survey of mentors. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20:1014–1018. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.215.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wasserstein AG, Quistberg DA, Shea JA. Mentoring at the University of Pennsylvania: results of a faculty survey. J Gen Intern Med. 2007; 210-214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 26.Johnson JK, Woods DM, Stevens DP, Bowen JL, Provost LP, Sixta CS, Wagner EH. Joy and challenges in improving chronic care: Capturing daily experience of academic primary care teams. J Gen Intern Med. 2010; 25:XX. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.Beasely BW, Simon SD, Wright SM. A time to be promoted. The prospective study of promotion in academia. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21:123–129. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.00297.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.IHI Health Professions Collaborative. Selected Projects and Activities FY 2005. http://www.ihi.org/IHI/Topics/HealthProfessionsEducation/EducationGeneral/EmergingContent/IHIHealthProfessionsCollaborativeSelectedProjectsandActivitiesFY05.htm. Accessed June 3, 2010.

- 29.Contemporary issues in medicine: quality of care. Washington DC: Association of American Medical Colleges; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Davidoff F, Batalden P, Stevens D, Ogrinc G, Mooney S. Publication guidelines for quality improvement in health care: evolution of the SQUIRE project. Qual Saf Health Care. 2008;17(Suppl 1):i3–i9. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2008.029066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.SQUIRE Standards for Quality Improvement Reporting Excellence. http://squire-statement.org/. Accessed June 3, 2010.

- 32.Rubenstein LV, Hempel S, Farmer MM, Asch SM, Yano EM, Dougherty D, Shekelle PW. Finding order in heterogeneity: types of quality improvement intervention publications. Qual Saf Health Care. 2008;17:403–408. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2008.028423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Batalden P, Leach D, Swing S, Dreyfus H, Dreyfus S. General competencies and accreditation in graduate medical education. Health Aff (Millwood) 2002;21:103–111. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.21.5.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Boonyasai RT, Windish DM, Chakraborti C, Feldmon LS, Rubin H, Bass EB. Effectiveness of teaching quality improvement to clinicians. JAMA. 2007;298:1023–1037. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.9.1023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Batalden P, Davidoff F. Teaching quality improvement: The devil is in the details. JAMA. 2007;298:1059–1061. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.9.1059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Patow CA, Karpovich K, Riesenberg LA, Jaeger J, Rosenfeld JC, Wittenbreer M, Padmore JS. Residents’ engagement in quality improvement: a systematic review of the literature. Acad Med. 2009;84:1757–1764. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181bf53ab. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Batalden PB, Davidoff F. What is “quality improvement” and how can it transform healthcare? Qual Saf Health Care. 2007;16:2–3. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2006.022046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]