Abstract

Objective

The purpose of this study was to improve the fund of knowledge, reduce cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk, and attain Healthy People 2010 objectives among women in model women's heart programs.

Methods

A 6-month pre/post-longitudinal educational intervention of high-risk women (n = 1310) patients at six U.S. women's heart programs consisted of comprehensive heart health counseling and use of American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology (AHA/ACC) Evidence-Based Guidelines as enhancement to usual care delivered via five integrated components: education/awareness, screening/risk assessment, diagnostic testing/treatment, lifestyle modification/rehabilitation, and tracking/evaluation. Demographics, before and after knowledge surveys, clinical diagnoses, laboratory parameters, and Framingham risk scores were also determined. Changes in fund of knowledge, awareness, and risk reduction outcomes and Healthy People 2010 objectives were determined.

Results

At 6 months, there were statistically significant improvements in fund of knowledge, risk awareness, and clinical outcomes. Participants attained or exceeded >90% of the Healthy People 2010 objectives. Proportions of participants showing increased knowledge and awareness of CVD as the leading killer of women, of all signs and symptoms of a heart attack, and calling 911 increased significantly (11.1%, 25.4%, and 34.6%, respectively). Health behavior counseling for physical activity, diet, and diabetes as CVD risk factors increased significantly (28.3%, 28.2%, and 12.5%, respectively). There was a statistical 4.1% increase in participants with systolic blood pressure (SBP) <140/90 mm Hg, a 4.7% decrease in participants with total cholesterol (TC) >240 mg/dL, a 4.5% decrease in participants with TC >200 mg/dL, a 5.9% decrease in participants with high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) <50 mg/dL, a 4.4% decrease in participants with HDL-C <40 mg/dL, and an 8.8% increase in diabetics with low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) <100 mg/dL.

Conclusions

CVD prevention built around a comprehensive heart care model program and AHA/ACC Evidence-Based Guidelines can be successful in improving knowledge and awareness, CVD risk factor reduction, and attainment of Healthy People 2010 objectives in high-risk women. Thus, these programs could have a dramatic and lasting impact on the health of women.

Introduction

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is the leading cause of death for women in the United States. According to American Heart Association (AHA) statistics (www.americanheart.org) and other sources, mortality attributable to CVD in women continues to outpace that in men.1,2 Compared with men, women have higher stroke mortality, higher morbidity after a heart attack, lower awareness of CVD, and a higher prevalence of risk factors for CVD, such as hypertension and hyperlipidemia.3–5 The higher mortality from myocardial infarction (MI) in women is attributable to older age and greater comorbidity at the time of MI in women compared with men. However, lack of awareness of threat remains a concern.6,7 A 2006 national survey conducted by the AHA found that 27% of women cite breast cancer as their greatest health threat, and only 21% of women believe their leading health threat to be CVD.3

Universal implementation and routine use of existing guidelines, specifically joint American Heart Association and American College of Cardiology (AHA/ACC) Evidence-Based Guidelines for CVD Prevention in Women, initially published in 20048 and subsequently revised in 2007,9 is needed, as women are still not benefiting equally from effective risk prevention strategies and lifesaving measures. CVD risk factors are prevalent in women yet often are unrecognized because of lack of appropriate screening and other factors. Two of three women have at least one of the following major CVD risk factors: high blood pressure, high cholesterol, diabetes, physical inactivity, and obesity.10,11 The association between diabetes and CVD is stronger in women than in men, and diabetes increases a woman's risk of developing CVD by 3–7 times, compared with 2–3 times in men.12 Hispanics have one of the highest rates of diabetes, and approximately 12% of adult African Americans have diabetes.

Differences in CVD outcomes and risk factor prevalence between women and men may be due, in part, to a lack of awareness among women and their physicians of the risks and symptoms for CVD in women5,10,13 and less aggressive use of treatments and preventive therapies for women than for men.13,14 Physicians rate women as lower risk for CVD than men, even when the men and women have similar risk scores by Framingham assessment,8,9 and counseling rates for exercise, nutrition, and weight reduction are suboptimal in women.14,15 In addition, women and healthcare providers are often ill-informed about the differences between male and female signs and symptoms for CVD, including for acute coronary syndromes.1,4,16–18

It is now well established that although the most common heart attack symptom in women and men is chest pain, important sex differences occur in chest pain and nonchest pain symptoms,1,19 complicating proper and timely recognition and evaluation of CVD in women. Minority women face additional health challenges directly related to personal behavior, access to healthcare, and genetics. For example, there are racial and ethnic disparities in CVD awareness, and African American women have the highest age-adjusted CVD death rate of any female race/ethnicity group in the United States.1,10,11 In 2005, the CVD death rate was 228.3/100,000 for African American women compared with 168.2/100,000 for white women and 172.3/100,000 for all women combined (www.womenshealth.gov/quickhealthdata/).

The purpose of the present CVD prevention study was to use a multifaceted intervention of comprehensive heart care involving medical screenings, health behavior counseling, risk behavior modification, and evidence-based guidelines for CVD prevention in women as enhancements to usual care to demonstrate what is achieved at model women's heart centers. The CVD prevention activities were built around a model of advocacy, resource knowledge, participant education, and implementation of the 2004 AHA/ACC Evidence-Based Guidelines for CVD Prevention in Women.8 Program activities were additionally designed to address Healthy People 2010 objectives (available at www.health.gov/healthypeople). We hypothesized that 6-month comprehensive CVD prevention programs implemented by women heart programs targeting high-risk women would attain 10 goals of Healthy People 2010 by providing screening and education, increasing knowledge and awareness of CVD (objective 12-2) and its attendant risk factors (objectives 5-5, 19-2, and 12-4), and reducing cardiovascular risk (objectives 1-31, 1-3b, 1-3c, 12-10, 12-16, and 22-2).

Materials and Methods

Performance sites

This study was sponsored by the U.S. Department of Human Health Services, Office on Women's Health (DHHS-OWH), with the goal of improving cardiovascular outcomes in high-risk women. To accomplish this goal, in 2005 OWH competed cooperative agreements for a program entitled “Improving, Enhancing and Evaluating Outcomes of Comprehensive Heart Care in High-Risk Women” to hospitals, clinics, and healthcare centers with existing women's heart healthcare programs. Six national participating study sites were selected as model women's heart programs as follows: each study site had access to large populations of high-risk women (racial and ethnic minority women aged ≥40 years) or partnered with community organization having such a network. Four of the study sites were academic medical centers and two were nonacademic institutions. A brief description of each study site and program is provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Description of Each Study Site and Women's Heart Program

| Name of program/URL | Academic/nonacademic | Number of women enrolled | Racial/ethnic minority women (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| The Heart of Woman (HOW) Program at Christ Community Health Service, Memphis, TN www.christcommunityhealth.org/ | Nonacademic | 177 | 98.9 |

| The Women's Cardiovascular Medicine Program at Columbia University, New York, NY www.cumc.columbia.edu/dept/cwh/ | Academic | 204 | 61.3 |

| The Women's Heart Center (WHC) at Fox Valley Cardiovascular Consultants, Aurora, IL www.foxvalleycardio.com | Nonacademic | 340 | 23.0 |

| The University of Minnesota Women's Heart Clinic, Minneapolis, MN www.ahc.umn.edu/wmhlth/ | Academic | 200 | 24.0 |

| The Yale New Haven Hospital Enhance Women's Heart Advantage Program www.ynhh.org/cardiac/heartadvantage.html | Academic | 200 | 31.5 |

| The Women's Cardiovascular Medicine Program at the University of California, Davis www.ucdmc.ucdavis.edu/internalmedicine/cardio/wcv_med_prog.html | Academic | 189 | 25.4 |

Participants and recruitment

From the patient population of the participating women's heart programs, 1310 women were recruited and were enrolled in the study from January 2006 to June 2007. High-risk women in the following groups were targeted for the study: women aged >60 years, racial and ethnic minority women, and women who lived in rural communities. Each participating study site targeted an underrepresented population of women based on the organization's history of prior collaboration or direct programmatic delivery with the selected organization or group. However, all high-risk women were eligible to participate in the program regardless of race, religion, or age. Recruitment strategies included program announcements and advertisements, fliers, website announcements, and health professional referrals. The Human Subjects Review Panels of each of the participating study site organization or institutions approved this study, and all participants provided informed consent.

Study design and program implementation

This was a pre/post-evaluation of an educational intervention conducted between September 2005 and June 2008. Follow-up was conducted at 6 months. The 6-month outcomes were compared with Healthy People 2010 goals and objectives at baseline (preintervention) and at 6 months postintervention for women enrolled in the study by the participating women's heart centers. There was no control group. The women's heart centers enrolled all new patients coming into their clinics for care, and none of the study participants were women who were previously followed in the clinic. No historical data are available on the women's heart centers before the study intervention because all centers received funding to implement tracking on new patients, which prior to the award, they did not have.

The enhanced care program was based in part on an intervention that delivered care using ACC/AHA Evidence-Based Guidelines for CVD Prevention in Women, using cutoff points defined therein. It should be noted that the ACC/AHA Evidence-Based Guidelines were being routinely implemented and followed in the women's heart centers before the study intervention, but their efficacy was not being tracked. The grant allowed the heart centers to track guideline implementation and outcomes related to implementation. In addition, the grant permitted each women's heart center to enhance its existing educational efforts to ensure the guidelines were being followed.

The intervention also focused on heart health education about sex differences in CVD symptoms, risk factor prevalence, and CVD as the leading killer of women. Educational interventions included instruction on heart healthy recipes and food preparation. Recipes addressed race/ethnicity in their content (e.g., heart healthy soul food, Hispanic healthy cooking) and low sodium dietary goals and body mass index (BMI) goals for women. The heart centers implemented care with an awareness of gender issues in cardiac diagnostics (e.g., breast attenuation with nuclear myocardial perfusion imaging) and rehabilitation (e.g., addressing lower participation/higher dropout rates in women, different exercise for women and men).

The primary goal of the program was to provide a comprehensive continuum of services to reduce CVD risk among women and to attain Healthy People 2010 goals. The enhanced intervention had five components: (1) education and awareness, (2) screening and risk assessment, (3) diagnostic testing and treatment, (4) lifestyle modification and cardiac rehabilitation, and (5) tracking and evaluation. The key features of each component are briefly summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Summary of the Five Components of Enhanced Women's Heart Programs

| 1. Education and awareness | 2. Screening and risk assessment | 3. Diagnosis and treatment | 4. Lifestyle modification | 5. Tracking and evaluation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Goals | ||||

| Raise awareness of: CVD as no.1 killer of women Prevention and control of CVD risk factors Symptoms and signs of heart attack/stroke Seeking emergency care by calling 911 |

Stratified women into Framingham 10-year event risk categories (high, intermediate, and lower) | Employ an evidence-based strategy in diagnostic testing and treatment of women to improve identification and management of CVD risk factors | Motivate behavioral change | Assess overall success of program in attaining outcomes |

| Motivate heart healthy living | Assess cohort demographics | Attain Healthy People 2010 goals | Improve health outcomes | |

| Promote use of AHA/ACC Evidence-Based Guidelines | Optimize use of diagnostic testing as needed (e.g., electrocardiogram, treadmill) | Increase adherence and participation | ||

| Emphasis and approach | ||||

| Each of six major CVD risk factors: Smoking Diabetes Cholesterol Hypertension Obesity Physical activity |

Medical histories: CVD risk factors Personal history of CVD | Assessment of risk factors: History Laboratory data |

Preventive cardiology capabilities of each study site (weight management, monitored exercise, educational sessions and programs) | Evaluate each component of the intervention |

| Stress | Health behavior counseling for each of the six major risk factors | Treatment of risk factors: Education Therapeutic lifestyle changes Pharmacologic therapy | ||

| Signs and symptoms of heart attack and stroke | Height, weight, BMI | Monitoring of response to therapy (history and laboratory data) | Evaluate quantitative data | |

| Calling 911 | Blood pressure (systolic and diastolic) | |||

| Preventive Interventions | Fasting blood sugar | |||

| Healthy lifestyles and benefits | Fasting lipids: Total cholesterol, LDL-C HDL-C |

Promoting long-term (6-month follow-up) treatment targets | Demonstrate study outcomes measures | |

| Framingham Global Risk Score risk stratification | ||||

| Demographics | ||||

| Tools | ||||

| Educational sessions and materials,a seminars, lectures, conferences, fact sheets | Self-reports, medical histories, medical records, laboratory studies, Framingham risk calculator,b surveysc | Linear multistep process | Educational sessions and counseling Cardiac rehabilitation | Data tracking, maintenance, analysis, and coordinating center |

National Institute's of Health's Heart Truth Campaign (www.womenshealth.gov/hearttruth/), American Heart Association materials (www.americanheart.org), with selected materials from each model women's heart program.

Framingham risk calculator (www.nhlbi.nih/gov/guidelines/cholesterol).

Surveys adapted from two validated survey instruments: the National Health Interview Survey (National Center for Health Statistics) and the American Heart Association survey for tracking women's awareness of CVD.16,18

AHA/ACC, American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology; BMI, body mass index; CVD, cardiovascular disease; HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol.

Outcome variables and metrics

The programs were demonstration projects; thus, it was anticipated they would provide the evidence necessary to evaluate whether comprehensive women's heart healthcare programs are effective in lowering CVD risk in high-risk women and in attaining Healthy People 2010 objectives. A total of 21 education/awareness/clinical outcomes and suboutcomes were evaluated for the study CVD prevention intervention (Table 3). In selecting program outcomes, emphasis was placed on aligning outcomes and targets with the objectives and targets of Healthy People 2010 (www.health.gov/healthypeople).

Table 3.

Knowledge, Awareness, and Clinical Study Outcomes Assessed in Response to the Cardiovascular Disease Prevention Intervention

| 1. Increase proportion of women who are aware of all the symptoms and signs of a heart attack |

| 2. Increase proportion of women who are aware of calling 911 |

| 3. Increase proportion of women who are aware of all the symptoms and signs of a heart attack and of calling 911 |

| 4. Increase awareness of heart disease as the leading killer of women |

| 5. Increase proportion of women counseled about health behaviors: |

| Physical activity |

| Diet and nutrition |

| Smoking cessation (for smokers) |

| Diabetes education for (a) self-reported diabetics and (b) diagnosed diabetics |

| 6. Increase blood pressure control of hypertensive women. Definition: |

| (a) women previously diagnosed with hypertension with current SBP <140 or DBP <90 mm Hg, (b) women previously diagnosed with hypertension with current SBP <120 or DBP <80 mm Hg |

| 7. Reduce proportion of women with high TC: Definition: |

| (a) women with TC >240 mg/dL, (b) women with TC >200 mg/dL |

| 8. Increase proportion of women with diabetes who are (a) diagnosed and (b) have their diabetes under control. Definition: |

| (a) FBS >126 mg/dL, (b) FBS <126 mg/dL |

| 9. Reduce proportion of women who are obese. Definition: |

| (a) women with BMI >30 kg/m2, (b) mean BMI <30 kg/m2 |

| 10. Increase proportion of women engaging in physical activity for 30 min/day |

| 11. Increase proportion of women with CHD with LDL-C treated to <100 mg/dL |

| 12. Increase proportion of women with diabetes with LDL-C treated to <100 mg/dL |

| 13. Reduce the proportion of women with low HDL-C. Definition: |

| (a) HDL-C <40 mg/dl, (b) HDL-C <50 mg/dl |

CHD, coronary heart disease; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; FBS, fasting blood sugar; SBP, systolic blood pressure; TC, total cholesterol.

Data coordinating center, data management, and data analysis

The Women's Cardiovascular Medicine Program at the University of California, Davis, was the data coordinating center (DCC) for this program and performed all data and statistical analyses for the study. A unique joint data interface and database were developed for this program20 and stored in the UC Davis Clinical and Translational Science Center (CTSC). Data analysis was performed by the UC Davis Division of Biostatistics and Center for Health Services Research on a recharge basis. Study investigators agreed to share their data and findings with the DCC via a signed data sharing and use agreement. The analysis was conducted with data accumulated from six participating centers in the United States, pooled for all centers. Baseline and 6-month follow-up data from risk and knowledge assessments, screenings, diagnostic tests, treatment plans, and interventions were collected by study sites, entered into a local central database, and uploaded to the DCC using a unique numeric identifier for each participant and using defined templates and data definitions. Thus, the joint outcomes reports combine a summary of data from all programs into a final evaluation of the CVD programs.

Data were analyzed using SAS/STAT® software (SAS Institute, Inc.,). For analysis, survey answer choices were recoded to reflect presence or absence of knowledge/health state/behavior (e.g., 0, does not know all symptoms for heart attack; 1, knows all symptoms for heart attack; 0, not obese, 1, obese; 0, does not do regular moderate exercise, 1, does regular moderate exercise). Next, frequency tables were generated for demographic, clinical, and knowledge variables as well as subgroups (e.g., age, race/ethnicity, education, site), and the proportion of participants in each knowledge/health state/behavior was calculated at baseline. For quantitative variables, arithmetic means and standard deviations (SDs) were calculated. Change over time toward desirable knowledge, health state, and behavior was assessed descriptively by frequency tables, overall and by site, for status at baseline and at 6 months for participants with data at both times. For study outcomes that apply only to some participants (e.g., smoking cessation advice is relevant only for current smokers), analysis was restricted to those in the relevant group at baseline. Paired comparisons were used to test for change (McNemar's test for yes/no questions, paired t tests or Wilcoxon signed rank for interval-scaled items). Chi-square tests were used to determine for each outcome variable if there were differences across sites in the proportion of women who moved from high-risk status at baseline to the desired outcome at 6 months. All statistical significance tests were at the α = 0.05 level.

All definitions of outcome targets were based on Health People 2010 goals or other prespecified targets, including choice of cutoff points for continuous variables. Exact tests were used if sample sizes were too small to meet the asymptotic assumptions of chi-square tests. Tests of mean change assumed normality, but this assumption was validated graphically and with the Shapiro-Wilk test and secondary nonparametric analyses (Wilcoxon signed-rank tests) were planned in case of nonnormality.

Results

Participant characteristics

Table 4 shows the demographic characteristics of all participants at baseline and per site. Overall, more than half of the cohort (55.1%) was 40–60 years of age, and over a third (39.3%) were black or Hispanic (24.6% and 14.7%, respectively). Most participants resided in urban areas, were not college graduates (total of 60.2%), and had health insurance. Three quarters of participants had a yearly income <$75,000.

Table 4.

Baseline Demographics of Study Population

| |

Total cohort |

Site 1 |

Site 2 |

Site 3 |

Site 4 |

Site 5 |

Site 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |

1310 |

177 |

204 |

340 |

200 |

200 |

189 |

| Characteristic | % enrollees | ||||||

| Age, years, mean (range) | 55.7 (20–86) | 50.9 (20–85) | 57.7 (21–84) | 61.6 (23–85) | 50.8 (20–83) | 54.4 (35–82) | 54.3 (21–86) |

| <40 | 10.1 | 21.0 | 5.4 | 6.2 | 16.5 | 7.5 | 8.0 |

| 40–59 | 55.1 | 54.6 | 53.9 | 37.7 | 65.0 | 66.0 | 67.0 |

| 60+ | 34.7 | 24.4 | 40.7 | 56.2 | 18.5 | 26.5 | 25.0 |

| Race/ethnicity | |||||||

| Caucasian (non-Hispanic) | 55.7 | 0.6 | 38.7 | 76.2 | 67.0 | 68.0 | 63.5 |

| Black (non-Hispanic) | 24.6 | 98.3 | 9.8 | 5.9 | 16.5 | 22.0 | 16.4 |

| Hispanic | 14.7 | – | 44.1 | 15.3 | 10.0 | 9.0 | 6.9 |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 1.7 | – | 0.5 | 1.5 | 6.0 | – | 2.1 |

| American Indians/Alaska natives | 0.3 | 0.6 | 6.9 | 0.3 | 0.5 | 0.5 | – |

| Other | 1.8 | – | – | 0.3 | – | 0.5 | 3.7 |

| Unknown/missing | 1.3 | 0.6 | – | 0.6 | – | – | 7.4 |

| Education | |||||||

| Some high school or less | 11.8 | 15.8 | 29.4 | 12.9 | 1.0 | 6.5 | 4.2 |

| High school graduate | 22.7 | 48.0 | 9.8 | 22.7 | 19.0 | 24.0 | 15.3 |

| Some college, vocational, or technical school | 25.4 | 26.6 | 11.3 | 27.4 | 23.5 | 30.0 | 33.3 |

| College graduate | 16.2 | 6.2 | 8.8 | 12.7 | 33.0 | 18.0 | 20.1 |

| Postgraduate | 15.1 | 0.6 | 27.9 | 6.5 | 23.5 | 21.5 | 14.8 |

| Unknown/missing | 8.8 | 2.8 | 12.8 | 17.9 | – | – | 12.2 |

| Geographic area | |||||||

| Rural | 1.4 | 0.6 | – | – | 8.5 | – | – |

| Suburban | 16.8 | 2.8 | 22.6 | – | 43.0 | 41.5 | – |

| Urban | 55.6 | 96.1 | 76.0 | – | 48.5 | 58.5 | 100.0 |

| Unknown/missing | 26.3 | 0.6 | 1.5 | 100.0 | – | – | – |

| Health insurance status | |||||||

| Medicaid or state | 14.6 | 29.9 | 47.6 | 2.9 | 5.0 | 10.5 | a |

| Medicare | 17.0 | 17.6 | – | 40.9 | 9.5 | 17.0 | a |

| HMO or other commercial | 46.0 | 11.3 | 52.0 | 49.7 | 85.0 | 68.5 | a |

| Private pay | 0.6 | 1.1 | – | 1.8 | – | – | a |

| None | 3.9 | 24.3 | – | – | 0.5 | 3.5 | a |

| Other | 2.0 | 11.3 | – | 1.5 | – | 0.5 | a |

| Unknown/missing | 16.0 | 4.5 | 0.5 | 3.2 | – | – | 100.0 |

| Socioeconomic status (income/year) | |||||||

| Up to $19,999 | 17.2 | 83.1 | a | 13.2 | 0.5 | 16.0 | a |

| $20,000–$39,999 | 10.9 | 14.1 | a | 23.8 | 3.5 | 15.0 | a |

| $40,000–$74,999 | 13.1 | 2.8 | a | 26.2 | 15.5 | 23.0 | a |

| ≥$75,000 | 24.1 | – | a | 23.8 | 80.5 | 36.5 | a |

| Unknown | 34.8 | – | 100.0 | 12.9 | – | 9.5 | 100.0 |

Some data collection was designated by U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office on Women's Health, as optional and centers did not have to collect it.

The cardiovascular risk profile of the study cohort is shown in Table 5 and confirms a high-risk cohort. Over half of the women had an intermediate to high Framingham risk score for a future CVD event in the next 10 years. Nearly one quarter were diabetic, and 15% had established CVD. Furthermore, 4 of 10 women were hypertensive (42%), and on antihypertensive medications (41%), yet 34% reported poor blood pressure control: systolic blood pressure (SBP) ≥140 or diastolic blood pressure (DBP) ≥90 mm Hg. Over 38% of women were obese (BMI >30 kg/m2), with a mean cohort BMI of 32.2. Nearly 40% of women were hyperlipidemic with total cholesterol (TC) >200 mg/dL and high-density liproprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) <50 mg/dL.

Table 5.

Baseline Cardiovascular Risk Profile of Study Participants

| |

Total cohort % |

Site 1 |

Site 2 |

Site 3 |

Site 4 |

Site 5 |

Site 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic (risk variable) | (n = 1310) | % enrollees | |||||

| Framingham risk category | |||||||

| Low (<10% 10-year risk) | 44.9 | 7.3 | 41.7 | 30.3 | 82.0 | 68.0 | 40.2 |

| Intermediate (10%–20% 10-year risk) | 9.2 | 8.5 | 4.4 | 9.7 | 18.0 | 1.5 | 13.2 |

| High (>20% 10-year risk) | 42.5 | 42.4 | 49.5 | 60 | – | 17.0 | 43.4 |

| Unknown/missing | 12.6 | 41.8 | 4.4 | 0 | – | 13.5 | 3.2 |

| Diabetes Mellitus (self-report) | |||||||

| Yes | 23.6 | 28.8 | 49.5 | 25.9 | 5.5 | 10.0 | 20.5 |

| No | 72.1 | 70.1 | 50.5 | 72.1 | 94.5 | 90.0 | 56.1 |

| Unknown/missing | 4.3 | 1.1 | – | 2.1 | – | – | 23.4 |

| Diabetes mellitus (diagnosis/history) | |||||||

| Yes | 24.9 | 26.6 | 50.5 | 28.5 | 5.5 | 10.5 | 24.9 |

| No | 75.1 | 73.5 | 49.5 | 71.5 | 94.5 | 89.5 | 75.1 |

| Diabetes mellitus (FBS ≥126 mg/dL) | |||||||

| Yes | 10.2 | 11.3 | 20.6 | 12.1 | 4.0 | 3.0 | 9.0 |

| No | 64.7 | 35.0 | 71.6 | 80.9 | 93.5 | 26.0 | 66.1 |

| Unknown/missing | 25.1 | 53.7 | 7.8 | 7.1 | 2.5 | 71.0 | 24.9 |

| Hypertension (diagnosis/history) | |||||||

| Yes | 51.1 | 49.2 | 1.0 | 63.8 | 31.0 | 42.0 | 39.7 |

| No | 46.4 | 50.9 | 99.0 | 36.2 | 69.0 | 58.0 | 42.9 |

| Unknown/missing | 2.5 | – | – | – | – | – | 17.5 |

| Hypertension | |||||||

| SBP ≥140 or DBP ≥90 mm Hg | |||||||

| Yes | 30.9 | 35.0 | 34.8 | 36.8 | 31.0 | 23.0 | 20.6 |

| No | 65.2 | 61.6 | 59.3 | 63.2 | 69.0 | 77.0 | 61.9 |

| Unknown/missing | 3.9 | 3.4 | 5.9 | – | – | – | 17.5 |

| Hypertension | |||||||

| SBP ≥120 or DBP ≥80 mm Hg | |||||||

| Yes | 71.6 | 81.9 | 77.0 | 74.7 | 64.0 | 73.0 | 57.1 |

| No | 24.5 | 14.7 | 17.2 | 25.3 | 36.0 | 27.0 | 25.4 |

| Unknown/missing | 3.9 | 3.4 | 5.9 | – | – | – | 17.5 |

| CAD (diagnosis/history) | |||||||

| Yes | 15.0 | 10.0 | 1.0 | 34.7 | 2.5 | 6.5 | 22.2 |

| No | 85.0 | 90.4 | 99.0 | 65.3 | 97.5 | 93.5 | 77.8 |

| Hypercholesterolemia | |||||||

| TC >240 mg/dL | 12.2 | 13.3 | 10.4 | 10.8 | 30.3 | 57.4 | 63.2 |

| TC >200 mg/dL | 39.1 | 47.6 | 44.0 | 31.1 | 6.6 | 10.4 | 17.6 |

| HDL-C <40 mg/dL | 13.0 | 9.9 | 8.8 | 18.9 | 7.0 | 5.7 | 25.6 |

| HDL-C <50 mg/dL | 37.8 | 37.0 | 34.4 | 47.0 | 23.1 | 25.3 | 59.7 |

| Obesity | 50.3 | 80.7 | 38.8 | 49.4 | 35.0 | 44.7 | 61.0 |

| BMI (mean) | 30.8 | 36.3 | 29.1 | 30.3 | 28.3 | 30.5 | 32.1 |

CAD, coronary artery disease.

Global outcomes

Before/after changes in outcomes were assessed at 6 months and compared to baseline for women who had data at both times (39%–61% of the original sample, depending on the outcome). Baseline characteristics for women with complete data were similar to those without (data not shown). Results summarize the proportion of women (% of enrollees) who increased or decreased in predetermined knowledge, awareness, and educational parameters, the proportion who attained reductions in clinical parameters, and the proportion that met or exceeded applicable Healthy People 2010 goals. Table 6 summarizes study results for knowledge and awareness of CVD as the leading killer or women; symptoms and taking appropriate action; health behavior counseling for CVD risk factor; intervention for each six of the major CVD risk factors; and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) target goal attainment for diabetics and women with established CVD.

Table 6.

Effects of Intervention on Cardiovascular Knowledge, Awareness, and Clinical Outcomes and Healthy People 2010 Goals

| |

Baseline |

6 months |

pavalue |

Targetb(%) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome (Healthy People 2010 goal number) | (% enrollees) | Target achieved | |||

| Knowledge and awareness | |||||

| All signs and symptoms of a heart attack (12-2) | 38.8 | 64.2 | <0.001 | >50 | Yes |

| Calling 911 (12-2) | 55.9 | 90.5 | <0.001 | NA | NA |

| All signs and symptoms and calling 911 (12-2) | 25.1 | 60.5 | <0.001 | NA | NA |

| Heart disease as #1 killer | 74.7 | 85.8 | <0.001 | >75 | Yes |

| Counseling, health behaviors | |||||

| Physical activity (1-3a) | 63.5 | 91.8 | <0.001 | >58 | Yes |

| Diet (1-3b) | 62.1 | 90.3 | <0.001 | >56 | Yes |

| Smoking cessation (if smoker) (1-3c) | 96.6 | 91.5 | 0.45 | >72 | Yes |

| Diabetes education (if self-report) | 61.0 | 73.5 | .001 | >60 | Yes |

| Risk factor control | |||||

| Obesity (BMI >30 kg/m2) (19-2) | 52.8 | 52.1 | 0.50 | <15 | No |

| Mean BMI (kg/m2) | 30.9 | 31.0 | 0.08 | NA | NA |

| Physical activity (30 min/day) (22-2) | 38.8 | 33.9 | 0.010 | >30 | Yes |

| BP control (<140/90 mm Hg) (12-20) | 33.4 | 37.5 | 0.026 | >50 | Yes |

| BP control (<120/80 mm Hg) | 10.0 | 11.6 | 0.66 | NA | NA |

| TC >240 mg/dL (12-14) | 13.3 | 8.6 | 0.001 | <17 | Yes |

| TC >200 mg/dL | 35.1 | 30.6 | <0.028 | NA | NA |

| HDL-C <40 mg/dL | 14.1 | 9.7 | 0.001 | NA | NA |

| HDL-C <50 mg/dL | 42.5 | 36.6 | <0.001 | NA | NA |

| Diabetes control, FBS <126 mg/dL | 52.5 | 52.5 | NA | NA | NA |

| Diabetes and CHD | |||||

| Diabetes diagnosed (5-4) | 94.8 | 91.6 | 0.21 | >80 | Yes |

| Diabetes and LDL-C <100 mg/dL | 44.8 | 53.6 | 0.039 | NA | NA |

| CHD and LDL-C <100 mg/dL (12-16) | 64.2 | 51.1 | 0.007 | NA | NA |

p value, baseline vs. 6-month comparisons; all analyses restricted to women with data at baseline and 6-month time points. McNemar test for comparing proportions, paired t test for means. For smoking question, only women who smoked at baseline were included; 24% of these women had quit smoking by the 6-month follow-up, including all women who did not report counseling on smoking prior to baseline. Women who no longer smoked were counted as receiving appropriate advice. For diabetes questions, only women who had a diagnosis of diabetes at baseline were included. For CHD, only women with CHD at baseline were included.

Targets based on targets set by objectives of Healthy People 2010, Office of Budget and Management measures for Department of Health and Human Services-Office on Women's Health, and RFA for Improving, Enhancing and Evaluating Outcomes of Comprehensive Heart Care in High-Risk Women (Federal Register, 2005; 70:36595). If the women were already at the HP 2010 target at baseline and remained so at the conclusion, the target, as defined by HP2010, was marked as achieved.

NA, not available.

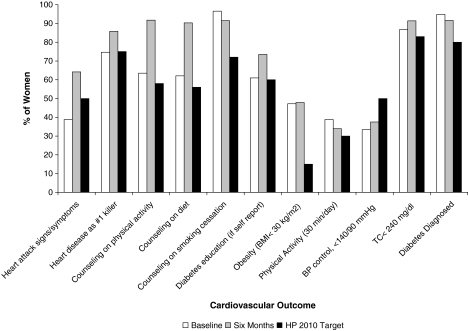

Overall, the 6-month intervention yielded significant improvement in all but 6 of the study's 21 joint outcomes and met nearly all Healthy People 2010 goals compared to baseline (Fig. 1). The study intervention was most successful in increasing knowledge and awareness outcomes (100% of outcomes attained), health behavior counseling for physical activity and a heart healthy diet, control of hypertensive and hyperlipidemic subjects, and LDL target goals of <100 mg/dl for diabetics and women with established CVD.

FIG. 1.

Effects of the intervention on attaining Healthy People 2010 and other study cardiovascular outcomes. Cardiovascular outcomes (percent of women attaining each outcome) at baseline and 6 months for women enrolled in the study. All comparisons are paired (preintervention and 6-month differences) for women with data at both time points. Outcomes definitions and Healthy People 2010 and other target goals were rescaled so that the direction of all cardiovascular outcome effects is positive (target goals defined in Table 6). BMI, body mass index; TC, total cholesterol.

Effect of intervention on knowledge and awareness of CVD, symptoms, and taking action

We assessed the participant's knowledge and awareness of (1) CVD as the leading killer of women, (2) the early warning symptoms and signs of a heart attack, and (3) accessing rapid emergency care by calling 911. Baseline knowledge and awareness were lowest for symptoms of a heart attack, with <40% identifying all symptoms and only a quarter knowing both the symptoms and to call 911 (Table 6). About three quarters knew that CVD is the leading killer of women and knew to call 911 for symptoms of a heart attack. All knowledge and awareness study outcomes improved significantly by 6 months (Fig. 1), and the applicable Healthy People 2010 goal was attained and exceeded (goal 12-2) (Table 6).

Effect of intervention on risk behavior counseling

We assessed the effect of the educational intervention on increasing the proportion of women who were asked or given advice by their healthcare provider in the last 12 months regarding the following four CVD risk interventions: (1) physical activity, (2) diet and nutrition, (3) smoking cessation for smokers, and (4) diabetes education and self-management for diabetics. At baseline, a relatively high proportion of participants had received prior health behavior counseling by a health professional for these CVD risk factors (61%–97% of participants, depending on the risk factor) (Fig. 1). As a result of the study intervention, however, there was an additional and significant increase in health behavior counseling for all outcomes, with counseling for diabetes, diet, and physical activity increasing by 12.5%, 28.2%, and 28.3%, respectively. Smoking cessation counseling was >90% at baseline. Thus, all the applicable Healthy People 2010 goals were met for this set of outcomes (goal 1-3a, 1-3b, and 1-3c) (Fig. 1).

Effect of intervention on CVD risk factor control

We evaluated the effect of the intervention on each of six major CVD risk factors: obesity, physical activity, hypertension, diabetes, and cholesterol (TC and HDL-C). All clinical parameters were defined as summarized in Table 6. We observed a significant 4.1% increase in the proportion whose blood pressure was controlled and below hypertensive levels of SBP 140 mm Hg and DBP 90 mm Hg, although there was no significant change in the proportion controlled to levels of SBP ≤120 and DBP ≤80. We observed a significant 4.7% decrease in the proportion of women with TC >240 mg/dL and a significant 4.5% decrease in the proportion of women with TC >200 mg/dL. The proportion with HDL-C <50 mg/dL decreased significantly by 5.9%, and the proportion with HDL-C <40 mg/dL decreased significantly by 4.4%. At baseline, approximately half the participants were obese (BMI ≥30 kg/m2) and half of diabetics had poor glucose control (FBS ≥126 mg/dL); Following the 6-month intervention, we did not observe any significant reduction in these proportions. We did not observe an increase in the proportion of women who engaged in physical activity (regular, moderate physical activity for at least 30 minutes per day). Nonetheless, except for obesity and physical activity (goals 19-2 and 22-2), all the applicable Healthy People 2010 goals for this set of outcomes were attained (goals 5-4, 12-14, and 12-20) (Fig. 1). The mean changes, SD, and median changes in all categorical variables are provided in Table 7.

Table 7.

Changes in All Study Categorical Clinical Variables

| |

n |

Mean change (absolute value) |

Standard deviation |

Median change (absolute value) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | (baseline vs. 6 months difference) | |||

| Systolic blood pressure | 689 | −3.1 | 18.2 | −2.0 |

| Diastolic blood pressure | 688 | 0.4 | 10.8 | 0 |

| Total cholesterol | 513 | −7.8 | 38.4 | 0 |

| Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol | 521 | −7.1 | 31.3 | 0 |

| High-density lipoprotein cholesterol | 525 | 1.2 | 7.8 | 0 |

| Fasting blood sugar | 473 | −0.7 | 24.2 | 0 |

| Body mass index | 701 | −0.2 | 2.4 | 0 |

Effect of intervention on diabetes, CVD, and LDL-C targets

Established CVD and diabetes as a CVD risk equivalent are high-risk prognosticators for future CVD events. Accordingly, AHA/ACC guidelines for control of LDL-C levels in these groups are stricter, with desirable LDL-C levels <100 mg/dL.8,9 We, therefore, were interested in determining if these target levels were attained as a result of the study intervention. There was a significant increase in the proportion of women with diabetes and women with CVD who had their LDL-C treated to a goal of <100 mg/dL (10.7% and 4.7% increase, respectively), thereby attaining Healthy People 2010 goal 12-16. The percent of diabetics who were diagnosed at baseline was very high in our cohort (>90%); therefore, the Healthy People 2010 goal to increase the proportion of diabetics who are diagnosed (goal 5-4) was met at baseline (Fig. 1). However, compared to baseline, there was a slight but not statistically significant decline in the number of diabetics diagnosed category during the intervention period (94.8% to 91.6%).

Outcomes in completers and noncompleters

There was active follow-up of participants through the use of scheduled reminders, calls, automated reminder notes, and so on. However, in some cases women went back to their primary care physicians for follow-up, in some cases the follow-up information was not available, and in many cases it was not linked electronically to the women's heart centers. Overall, 60% of the women who initially enrolled in the study completed the 6-month follow-up period. Women failed to have a 6-month follow-up for a number of factors, including relocating, ill health, hospitalization, or becoming lost to follow-up.

We examined baseline clinical and demographic characteristics of completers (n = 793) compared with noncompleters (n = 517) for 18 characteristics: education about physical activity, education about diet/nutrition, awareness of signs/symptoms of heart attack, awareness of heart disease as leading killer, awareness of taking appropriate action by calling 911, awareness of signs/symptoms of heart attack and calling 911, TC >200, TC >240, BMI >30, exercise, HDL <40, HDL <50, FBS >126, diagnosis of diabetes, diabetes self-report, SBP ≥140 or DBP ≥90, SBP ≥120 or DBP ≥80, and diagnosis of CVD. Completers and noncompleters were overall very similar in their characteristics and differed in only 3 of 18 characteristics: CVD diagnosis: completers 17.3%, noncompleters 10.4% (p <0.001); awareness of calling 911: completers 49.2%, noncompleters 83.6% (p <0.001); diabetes diagnosis: completers 20%, noncompleters 26.3% (p <0.005). At baseline, women who made it to 6 months of follow-up (completers) had significantly more CVD and significantly less diabetes and knowledge of taking appropriate action by calling 911 than women who did not follow up (noncompleters).

Discussion

According to the recent AHA/ACC Guidelines for women, “more rigorous testing of the impact of guidelines themselves on prevention of risk factors, slowing the progression of risk factors, and reducing the burden of CVD is needed.”9 “The development and testing of effective methods to implement guidelines in various health-care settings, at work sites and in communities are also research priorities.”9 Therefore, the goal of this study was to demonstrate outcomes by six U.S. model women's heart centers after an intervention to improve and enhance comprehensive heart care in high-risk women using a multifaceted education, awareness, and clinical care intervention following AHA/ACC Evidence-Based Guidelines for Heart Disease Prevention in Women. Our results show that, at 6 months postintervention, study participants made improvements in most of the outcomes of the study, with statistically significant gains compared to baseline. It is worthwhile to mention that relatively modest mean changes may be significant when they are considered at a population level. In addition, all but one of the relevant Healthy People 2010 goals were attained. In this program, nearly half of the participants were at Healthy People 2010 goals preintervention. However, even those at goal demonstrated further gains.

In terms of specific study outcomes, the program was successful in increasing awareness of all the CVD knowledge outcomes (signs and symptoms of a heart attack, CVD as the leading killer of women, taking appropriate action by calling 911) and in increasing counseling for risk factor modification interventions for most of the cardiovascular risk factors studied, particularly physical activity and a heart healthy diet. Knowledge and awareness of CVD as the leading killer was very high at baseline in our cohort (75%) and nearly twice the current national average.7 Perhaps this is attributable to the sustained local efforts and impact of the participating women's heart programs in the communities they serve. As well, knowledge of CVD as the leading killer improved further to 90% during the study.

The program was effective in helping participants to attain improved cardiovascular risk profiles. In this regard, the intervention was most successful in control of systolic hypertension (SBP >140/90 mm Hg). This may reflect the fact that hypertension was the most prevalent cardiovascular risk factor in our study population (51%). Analysis of individual-level SBP changes were generally consistent across sites, with no evidence of site-to-site differences (data not shown). Control of hyperlipidemia (TC >240 mg/dL and TC >200 mg/dL) appeared improved in response to the intervention. It may be the case that blood pressure and lipids were affected by counseling for exercise and nutrition to a greater extent than were other risk factors over the 6-month intervention period. The program was successful in treating high-risk diabetic women to LDL-C target goals of <100 mg/dL. At the completion of the 6-month study period, 60% of diabetics met this cholesterol goal. We had more diabetics who were noncompleters than completers (26.3% vs. 20%), and this likely accounted for the small decline in the diabetes diagnosed category.

The program was least successful in addressing obesity, increasing physical activity, and raising the HDL-C of the study participants. The lack of effectiveness of the intervention in improving these risk factors is concordant with the findings of prior studies indicating that they are difficult to modify and require sustained and specific strategies.14,15,21–23 A longer period of clinical intervention and readiness for change may be more effective for modifying weight.22 Mean BMI varied substantially among sites (range 28.1–36.3 kg/m2). However, mean BMI showed no significant reduction overall, with no evidence of site-specific clinically meaningful differences in outcomes.

As previously mentioned, we did not observe an increase in the proportion of women who engaged in physical activity (regular, moderate physical activity for at least 30 minutes per day). Length of time, intensity of exercise, and frequency of exercise21 may each need to be evaluated separately to discern whether there are specific elements responsive to the type of intervention implemented in this study. Although we are not certain of the exact cause for the 5% decline in physical activity we observed, we considered the following: The women received more information and teaching on diet and nutrition than on exercise as interventions. This was generally the case for most if not all of the women's heart centers, as they had greater access to a dietitian than to an exercise physiologist, and this could, therefore, have been a factor. In addition, although we educated women about physical activity, motivation may have played a role in our results. We are not able to assess this, however, as we did not assess stage of change in this study. We also did not assess for comorbidities that may have limited ability to exercise, including worsening heart disease. The difference in exercise could be due to differences between completers and noncompleters. We performed chi-square analyses to test if there were differences in exercise for the two clinical characteristics (diabetics and CVD) that differed between completers and noncompleters. However, we did not find any statistical differences in exercise that were attributable to differences in diabetes or CVD prevalence between completers and noncompleters. There has been a national trend of a decline in physical activity in women, and the decline we observed over the 2-year period of the study may reflect this trend. Overall, women are at lower levels of physical activity than what is recommended. For example, the women and heart disease statistics of the AHA (www.americanheart.org/presenter.jhtml?identifier=3000090) indicate that only 28.9% of women have regular physical activity. We also looked at some age-adjusted Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS, www.cdc.gov/brfss/) results for California and the other states of the heart centers that participated in this study for exercise. On average, 22% of women in the women's heart centers states (range 19.2%–26.1%) had moderate physical activity, whereas well over 30% of women in our heart centers had moderate physical activity levels during the period of our study. Therefore, compared with AHA and BRFSS data, our cohort was in all cases more physically active, both at baseline and at the study conclusion.

Attainment of study follow-up was 60%, despite appointment reminders, phone calls to participants, announcements of educational activities, and feedback of progress and results. Many of the women who participated and continued in the program did so out of a strong desire to be a part of a clinical care delivery that was women centered and evidence based and that focused on their perception of an important health issue.

There were a number of lessons learned in the conduct of this study. When working with complex management systems, it is beneficial to align efforts with national guidelines and institutional resources to ensure that program implementation efforts are effective. CVD interventions for high-risk women should be designed to enhance the strengths of existing resources, should be inclusive of members of the target population during planning and implementation, and should identify race, culture, and gender as contributing factors to CVD. These strategies will help to ensure that high-risk women have a greater sense of accountability and self-worth in a program that was designed for them and that existing AHA/ACC Evidence-Based Guidelines for CVD prevention in women gain broader implementation.

The generalizability of our findings may be limited for several reasons. (1) The AHA/ACC Guidelines for CVD Prevention were revised and changed during the conduct of this program.10,14 Although the outcomes we studied were not substantially affected by the new guidelines, as clinical target goals remained largely unchanged, CVD risk categories were redefined and the role of the Framingham risk score was further specified. (2) We were unsuccessful in reaching sufficient numbers of women in rural settings because of geographic distance from study sites and established referral patterns, so that we are unable to determine if our findings have the same relevance to this group of women. (3) Although there was site heterogeneity in participant characteristics at baseline, at 6 months, the magnitude of outcome improvement was substantial across all sites (range 33%–100%, depending on the outcome). Nonetheless, the range in extent of improvement across sites warrants further study to determine differences in initial patient profiles as predictors of change. Caution also needs to be exercised in concluding that knowledge changes behavior. For example, in REACT,4 knowledge of heart attack symptoms increased, yet time to arrival in an emergency room did not. Furthermore, after cessation of a message, knowledge tends to decline quite rapidly.24 Additional limitations of our study include the following: participants were self-selected, there was a high noncompletion to usual care, and there was no information collected on medications. Because the AHA/ACC Evidence-Based Guidelines include the use of pharmacotherapy and pharmacotherapy was implemented in appropriate patients per the guidelines, medication use was not tracked separately.

In summary, the evolution of women's heart programs as institutional or community-based programs represents recognition of the need to address the major health threat to half of our population. The time has come to systematically address CVD in women and evaluate the importance of women's heart programs in this effort. The improved educational counseling and AHA/ACC Evidence-Based Care, delivered as a comprehensive program in women's cardiac centers via the five implementation components of this study, provide evidence that these demonstration projects are effective in positive CVD risk factor changes in high-risk women. Based on the combined experience of the six women's heart centers that formed part of this study, the incremental costs for these efforts are estimated to be relatively modest (approximately $92,267 per site and $70 per participant). Established Evidence-Based AHA/ACC Guidelines must be implemented and followed, and healthcare professionals, community and government organizations, and healthcare delivery systems must work in concert to stem the CVD epidemic in women. These approaches must, furthermore, be linear, integrated, and of high priority in healthcare policy and funding.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by cooperative agreement awards (HHCWH050001, HHCWH050002, HHCWH050003, HHCWH050004, HHCWH050005, and HHCWH050006) from The Office on Women's Health in the United States Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS/OWH) and the Office of Research on Women's Health at the National Institutes of Health (NIH/ORWH). This was also made possible by the Frances Lazda Endowment in Women's Cardiovascular Medicine to A.C.V. and grant number UL1 RR024146 from the National Center for Research Resources (NCRR) to UC Davis, a component of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), and NIH Roadmap for Medical Research. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official view of NCRR or NIH. Information on Reengineering the Clinical Research Enterprise can be found at nihroadmap.nih.gov/clinicalresearch/overview-translational.asp.

The authors acknowledge the following contributing investigators, research staff at each lead site, data coordinating staff, and others. The benefits and positive impact of the program activities are the direct result of the efforts of these organizations and individuals as follows:

DHHS-OWH: Suzanne Haynes, Ph.D., Senior science advisor; Lacy Koppelman, MSPH, Public health advisor. Christ Community Health Services: Shantelle Leatherwood, M.H.A., Principal investigator; Georgia Oliver, M.S., co-investigator; David Pepperman, M.D., Co-investigator; Richard Thomas, Ph.D., Co-investigator. Columbia University Medical Center: Elsa-Grace V. Giardina, M.D., Principal investigator; Elaine M. Fleck, M.D., Co-investigator; Amanda F. Ascher, M.D., Co-investigator; Bernadette Boden-Albala, Ph.D., Co-investigator; Stella M. Yala, M.D., Project coordinator; Darlene Castro, B.A., Project coordinator. Yale New Haven Medical Center: Gail D'Onofrio, M.D., M.S., Principal investigator; JoAnne Micale Foody, M.D., Co-principal investigator; Basmah Safdar, M.D., Co-investigator; Charlotte Hickey, R.N., M.S., Data and clinical coordinator; Zhenqui Lin, Ph.D., Statistician. University of Minnesota: Anne L. Taylor, M.D., Principal investigator; Becky Gams, R.N., M.S., C.N.P., Project coordinator; Carol Barron, R.N., Project coordinator; Lynn Hoke, N.P., R.N., M.S.N., Nurse specialist. Fox Valley: Santosh K. Gill, M.D., M.B.A., Principal investigator; Bonnie M. Resch, R.N., B.S., Research coordinator. University of California, Davis: Investigator Team: Amparo C. Villablanca, M.D., Principal investigator and director, Women's Cardiovascular Medicine Program; Seleda Williams, M.D., M.P.H., Collaborating investigator and public health medical officer, California Department of Health Services; Dianne Hyson, Ph.D., M.S., R.D., Collaborating investigator and assistant professor and director of the Didactic Program in Dietetics at California State University, Sacramento; Liana Lianov, M.D., M.P.H., Collaborating investigator and medical officer MediCal Managed Care, California Department of Health Services; University of California, Davis data team and staff: Christina Slee, Research assistant and data analyst; Cris Warford, Research assistant; Hassan Baxi, B.S., Data manager/computer programmer; Kent Anderson, B.S., Database architect; Susan Long, B.S., Clinical research coordinator; Pamela Nelson, Administrative assistant; Maureen Calpo, Administrative assistant.

Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Chen W. Woods SL. Puntillo KA. Gender differences in symptoms associated with acute myocardial infarction: A review of the research. Heart Lung. 2005;34:240–247. doi: 10.1016/j.hrtlng.2004.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chobanian AV. Bakris GL. Black HR, et al. Seventh report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure. Hypertension. 2003;42:1206–1252. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000107251.49515.c2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Christian AH. Rosamond W. White AR. Mosca L. Nine-year trends and racial and ethnic disparities in women's awareness of heart disease and stroke: An American Heart Association national study. J Womens Health. 2007;16:68–81. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2006.M072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goff DC., Jr. Mitchell P. Finnegan J, et al. Knowledge of heart attack symptoms in 20 U.S. communities. Results from the Rapid Early Action for Coronary Treatment Community Trial. Prev Med. 2004;38:85–93. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2003.09.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mosca L. Grundy SM. Judelson D, et al. Guide to preventive cardiology for women. AHA/ACC scientific statement Consensus panel statement. Circulation. 1999;99:2480–2484. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.99.18.2480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mosca L. Ferris A. Fabunmi R. Robertson RM. Tracking women's awareness of heart disease: An American Heart Association national study. Circulation. 2004;109:573–579. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000115222.69428.C9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mosca L. Mochari H. Christian A, et al. National study of women's awareness, preventive action, and barriers to cardiovascular health. Circulation. 2006;113:525–534. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.588103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mosca L. Appel LJ. Benjamin EJ, et al. Evidence-based guidelines for cardiovascular disease prevention in women. Circulation. 2004;109:672–693. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000114834.85476.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mosca L. Banka CL. Benjamin EJ, et al. Evidence-based guidelines for cardiovascular disease prevention in women: 2007 update. Circulation. 2007;115:1481–1501. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.181546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lethbridge-Cejku M. Schiller JS. Bernadel L. Summary health statistics for U.S. adults: National Health Interview Survey, 2002. Vital Health Stat. 2004;10:1–151. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rosamond W. Flegal K. Furie K, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2008 update: A report from the American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Circulation. 2008;117:e25–146. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.187998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huxley R. Barzi F. Woodward M. Excess risk of fatal coronary heart disease associated with diabetes in men and women: Meta-analysis of 37 prospective cohort studies. BMJ. 2006;332:73–78. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38678.389583.7C. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grady D. Chaput L. Kristof M. Results of systematic review of research on diagnosis and treatment of coronary heart disease in women. Evid Rep Technol Assess (Summ) 2003:1–4. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Masuo K. Mikami H. Ogihara T. Tuck ML. Weight reduction and pharmacologic treatment in obese hypertensives. Am J Hypertens. 2001;14:530–538. doi: 10.1016/s0895-7061(00)01279-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lyznicki JM. Young DC. Riggs JA. Davis RM. Obesity: Assessment and management in primary care. Am Fam Physician. 2001;63:2185–2196. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McSweeney JC. Cody M. Crane PB. Do you know them when you see them? Women's prodromal and acute symptoms of myocardial infarction. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2001;15:26–38. doi: 10.1097/00005082-200104000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Disparities in adult awareness of heart attack warning signs and symptoms—14 states. MMWR. 2008;57:175–179. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Patel H. Rosengren A. Ekman I. Symptoms in acute coronary syndromes: Does sex make a difference? Am Heart J. 2004;148:27–33. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2004.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lutfiyya MN. Cumba MT. McCullough JE. Barlow EL. Lipsky MS. Disparities in adult African American women's knowledge of heart attack and stroke symptomatology: An analysis of 2003–2005 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance Survey data. J Womens Health. 2008;17:805–813. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2007.0599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Villablanca AC. Baxi H. Anderson K. Novel data interface for evaluating cardiovascular outcomes in women. In: Dwivedi AN, editor. Handbook of research on information technology management and clinical data administration in healthcare. Hershey: IGI Global; 2009. pp. 34–53. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Frank LL. Sorensen BE. Yasui Y, et al. Effects of exercise on metabolic risk variables in overweight postmenopausal women: A randomized clinical trial. Obes Res. 2005;13:615–625. doi: 10.1038/oby.2005.66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Logue EE. Jarjoura DG. Sutton KS. Smucker WD. Baughman KR. Capers CF. Longitudinal relationship between elapsed time in the action stages of change and weight loss. Obes Res. 2004;12:1499–1508. doi: 10.1038/oby.2004.187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tinker LF. Patterson RE. Kristal AR, et al. Measurement characteristics of 2 different self-monitoring tools used in a dietary intervention study. J Am Diet Assoc. 2001;101:1031–1040. doi: 10.1016/S0002-8223(01)00254-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stellefson ML. Hanik BW. Chaney BH. Chaney JD. Factor retention in EFA: Strategies for health behavior researchers. Am J Health Behav. 2009;33:587–599. doi: 10.5993/ajhb.33.5.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]