Abstract

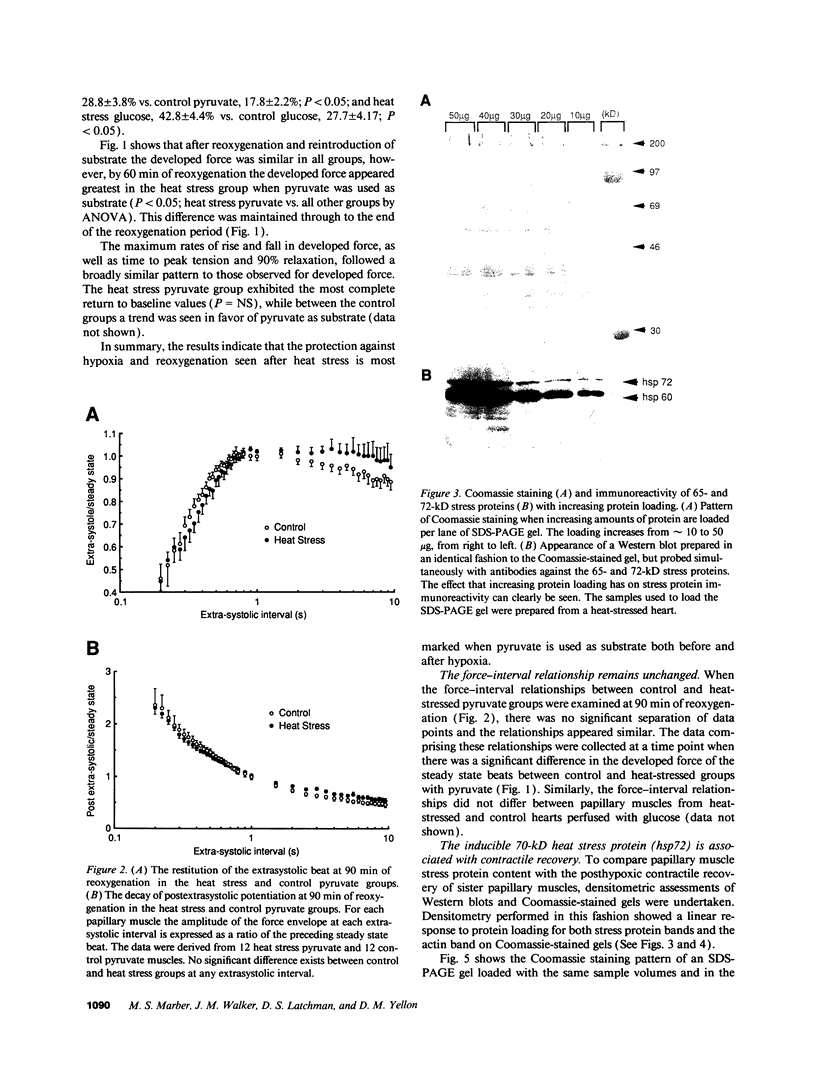

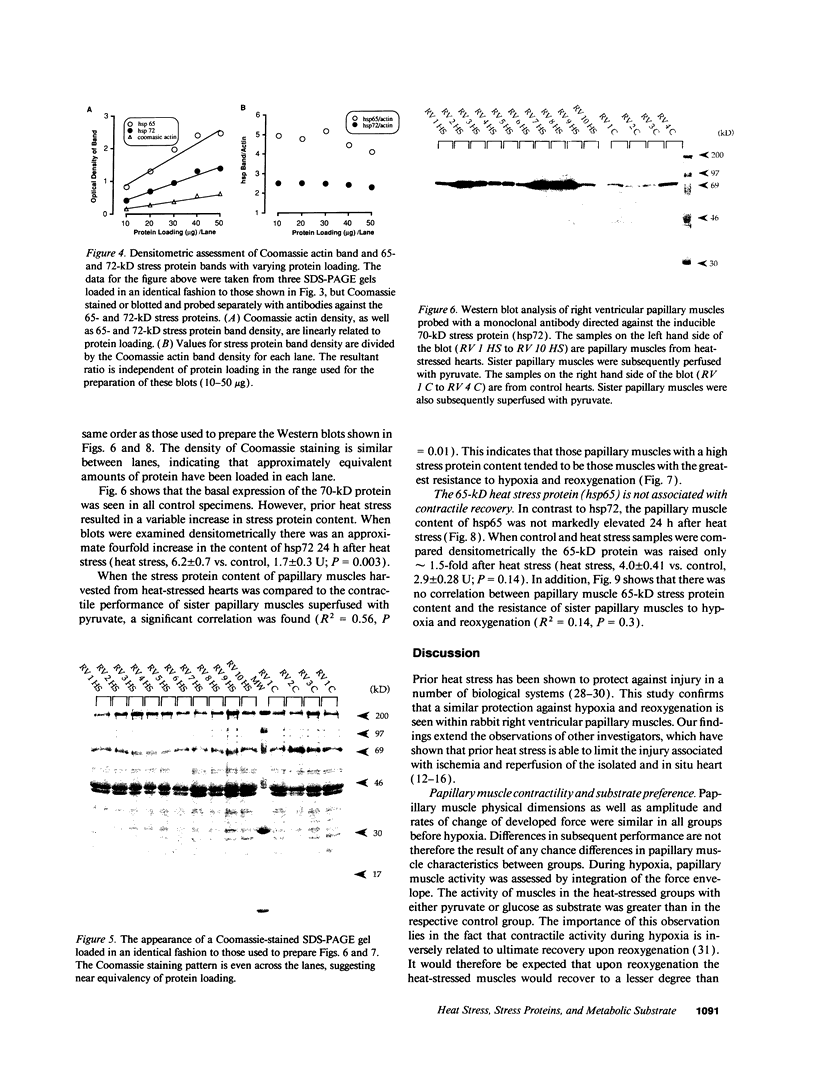

The aims of this study were to examine the effects of whole body heat stress and subsequent stress protein induction on glycolytic metabolism, mitochondrial metabolism, and calcium handling within the heart. The effect of heat stress on glycolytic and mitochondrial pathways was examined by measuring contractile performance in the presence of glucose and pyruvate, respectively. Calcium handling was assessed using force-interval relationships. Right ventricular papillary muscles taken from heat-stressed and control rabbit hearts were superfused with Kreb's solution containing either glucose or pyruvate and rendered hypoxic for 30 min. After reoxygenation, the greatest recovery of contractile function occurred in the heat-stressed muscles with pyruvate as substrate; there was, however, no difference in the force-interval relationship between the groups. The degree of contractile recovery was related to the content of the inducible 70-kD but not the 65-kD, heat stress protein. This study suggests that heat stress enhances the ability of rabbit papillary muscle to use pyruvate, but not glucose, after reoxygenation, and that the differences seen in contractility may be secondary to induction of the 72-kD stress protein.

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Allen D. G., Kurihara S. Calcium transients in mammalian ventricular muscle. Eur Heart J. 1980;Suppl A:5–15. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/1.suppl_1.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banijamali H. S., Gao W. D., MacIntosh B. R., ter Keurs H. E. Force-interval relations of twitches and cold contractures in rat cardiac trabeculae. Effect of ryanodine. Circ Res. 1991 Oct;69(4):937–948. doi: 10.1161/01.res.69.4.937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbe M. F., Tytell M., Gower D. J., Welch W. J. Hyperthermia protects against light damage in the rat retina. Science. 1988 Sep 30;241(4874):1817–1820. doi: 10.1126/science.3175623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavallini L., Valente M., Rigobello M. P. The protective action of pyruvate on recovery of ischemic rat heart: comparison with other oxidizable substrates. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1990 Feb;22(2):143–154. doi: 10.1016/0022-2828(90)91111-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng M. Y., Hartl F. U., Martin J., Pollock R. A., Kalousek F., Neupert W., Hallberg E. M., Hallberg R. L., Horwich A. L. Mitochondrial heat-shock protein hsp60 is essential for assembly of proteins imported into yeast mitochondria. Nature. 1989 Feb 16;337(6208):620–625. doi: 10.1038/337620a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chevalier B., Callens F., Charlemagne D., Delcayre C., Lompré A. M., Lelièvre L., Mercadier J. J., Moalic J. M., Mansier P., Rappaport L. Signal and adaptational changes in gene expression during cardiac overload. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1989 Dec;21 (Suppl 5):71–77. doi: 10.1016/0022-2828(89)90773-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chopp M., Chen H., Ho K. L., Dereski M. O., Brown E., Hetzel F. W., Welch K. M. Transient hyperthermia protects against subsequent forebrain ischemic cell damage in the rat. Neurology. 1989 Oct;39(10):1396–1398. doi: 10.1212/wnl.39.10.1396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper I. C., Fry C. H. Mechanical restitution in isolated mammalian myocardium: species differences and underlying mechanisms. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1990 Apr;22(4):439–452. doi: 10.1016/0022-2828(90)91479-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Currie R. W., Karmazyn M., Kloc M., Mailer K. Heat-shock response is associated with enhanced postischemic ventricular recovery. Circ Res. 1988 Sep;63(3):543–549. doi: 10.1161/01.res.63.3.543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Currie R. W., Tanguay R. M. Analysis of RNA for transcripts for catalase and SP71 in rat hearts after in vivo hyperthermia. Biochem Cell Biol. 1991 May-Jun;69(5-6):375–382. doi: 10.1139/o91-057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Currie R. W., Tanguay R. M., Kingma J. G., Jr Heat-shock response and limitation of tissue necrosis during occlusion/reperfusion in rabbit hearts. Circulation. 1993 Mar;87(3):963–971. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.87.3.963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delcayre C., Samuel J. L., Marotte F., Best-Belpomme M., Mercadier J. J., Rappaport L. Synthesis of stress proteins in rat cardiac myocytes 2-4 days after imposition of hemodynamic overload. J Clin Invest. 1988 Aug;82(2):460–468. doi: 10.1172/JCI113619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dillmann W. H., Mehta H. B., Barrieux A., Guth B. D., Neeley W. E., Ross J., Jr Ischemia of the dog heart induces the appearance of a cardiac mRNA coding for a protein with migration characteristics similar to heat-shock/stress protein 71. Circ Res. 1986 Jul;59(1):110–114. doi: 10.1161/01.res.59.1.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donnelly T. J., Sievers R. E., Vissern F. L., Welch W. J., Wolfe C. L. Heat shock protein induction in rat hearts. A role for improved myocardial salvage after ischemia and reperfusion? Circulation. 1992 Feb;85(2):769–778. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.85.2.769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabiato A., Fabiato F. Calcium release from the sarcoplasmic reticulum. Circ Res. 1977 Feb;40(2):119–129. doi: 10.1161/01.res.40.2.119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gwathmey J. K., Slawsky M. T., Hajjar R. J., Briggs G. M., Morgan J. P. Role of intracellular calcium handling in force-interval relationships of human ventricular myocardium. J Clin Invest. 1990 May;85(5):1599–1613. doi: 10.1172/JCI114611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hightower L. E. Heat shock, stress proteins, chaperones, and proteotoxicity. Cell. 1991 Jul 26;66(2):191–197. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90611-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang P. J., Ostermann J., Shilling J., Neupert W., Craig E. A., Pfanner N. Requirement for hsp70 in the mitochondrial matrix for translocation and folding of precursor proteins. Nature. 1990 Nov 8;348(6297):137–143. doi: 10.1038/348137a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karmazyn M., Mailer K., Currie R. W. Acquisition and decay of heat-shock-enhanced postischemic ventricular recovery. Am J Physiol. 1990 Aug;259(2 Pt 2):H424–H431. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1990.259.2.H424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knowlton A. A., Brecher P., Apstein C. S. Rapid expression of heat shock protein in the rabbit after brief cardiac ischemia. J Clin Invest. 1991 Jan;87(1):139–147. doi: 10.1172/JCI114963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knowlton A. A., Eberli F. R., Brecher P., Romo G. M., Owen A., Apstein C. S. A single myocardial stretch or decreased systolic fiber shortening stimulates the expression of heat shock protein 70 in the isolated, erythrocyte-perfused rabbit heart. J Clin Invest. 1991 Dec;88(6):2018–2025. doi: 10.1172/JCI115529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kukreja R. C., Hess M. L. The oxygen free radical system: from equations through membrane-protein interactions to cardiovascular injury and protection. Cardiovasc Res. 1992 Jul;26(7):641–655. doi: 10.1093/cvr/26.7.641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuzuya T., Hoshida S., Yamashita N., Fuji H., Oe H., Hori M., Kamada T., Tada M. Delayed effects of sublethal ischemia on the acquisition of tolerance to ischemia. Circ Res. 1993 Jun;72(6):1293–1299. doi: 10.1161/01.res.72.6.1293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laemmli U. K. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970 Aug 15;227(5259):680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis M. J., Grey A. C., Henderson A. H. Determinants of hypoxic contracture in isolated heart muscle preparations. Cardiovasc Res. 1979 Feb;13(2):86–94. doi: 10.1093/cvr/13.2.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li G. C., Werb Z. Correlation between synthesis of heat shock proteins and development of thermotolerance in Chinese hamster fibroblasts. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1982 May;79(10):3218–3222. doi: 10.1073/pnas.79.10.3218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Löw I., Friedrich T., Schoeppe W. Synthesis of shock proteins in cultured fetal mouse myocardial cells. Exp Cell Res. 1989 Feb;180(2):451–459. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(89)90071-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marber M. S., Latchman D. S., Walker J. M., Yellon D. M. Cardiac stress protein elevation 24 hours after brief ischemia or heat stress is associated with resistance to myocardial infarction. Circulation. 1993 Sep;88(3):1264–1272. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.88.3.1264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moalic J. M., Bauters C., Himbert D., Bercovici J., Mouas C., Guicheney P., Baudoin-Legros M., Rappaport L., Emanoil-Ravier R., Mezger V. Phenylephrine, vasopressin and angiotensin II as determinants of proto-oncogene and heat-shock protein gene expression in adult rat heart and aorta. J Hypertens. 1989 Mar;7(3):195–201. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller D. W., Topol E. J., Califf R. M., Sigmon K. N., Gorman L., George B. S., Kereiakes D. J., Lee K. L., Ellis S. G. Relationship between antecedent angina pectoris and short-term prognosis after thrombolytic therapy for acute myocardial infarction. Thrombolysis and Angioplasty in Myocardial Infarction (TAMI) Study Group. Am Heart J. 1990 Feb;119(2 Pt 1):224–231. doi: 10.1016/s0002-8703(05)80008-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norton P. M., Latchman D. S. Levels of the 90kd heat shock protein and resistance to glucocorticoid-mediated cell killing in a range of human and murine lymphocyte cell lines. J Steroid Biochem. 1989 Aug;33(2):149–154. doi: 10.1016/0022-4731(89)90288-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nowak T. S., Jr Protein synthesis and the heart shock/stress response after ischemia. Cerebrovasc Brain Metab Rev. 1990 Winter;2(4):345–366. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Opie L. H. Cardiac metabolism--emergence, decline, and resurgence. Part I. Cardiovasc Res. 1992 Aug;26(8):721–733. doi: 10.1093/cvr/26.8.721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pauly D. F., Kirk K. A., McMillin J. B. Carnitine palmitoyltransferase in cardiac ischemia. A potential site for altered fatty acid metabolism. Circ Res. 1991 Apr;68(4):1085–1094. doi: 10.1161/01.res.68.4.1085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perdrizet G. A., Kaneko H., Buckley T. M., Fishman M. A., Schweizer R. T. Heat shock protects pig kidneys against warm ischemic injury. Transplant Proc. 1990 Apr;22(2):460–461. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose D. W., Welch W. J., Kramer G., Hardesty B. Possible involvement of the 90-kDa heat shock protein in the regulation of protein synthesis. J Biol Chem. 1989 Apr 15;264(11):6239–6244. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schouten V. J., van Deen J. K., de Tombe P., Verveen A. A. Force-interval relationship in heart muscle of mammals. A calcium compartment model. Biophys J. 1987 Jan;51(1):13–26. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(87)83307-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seed W. A., Walker J. M. Review: Relation between beat interval and force of the heartbeat and its clinical implications. Cardiovasc Res. 1988 May;22(5):303–314. doi: 10.1093/cvr/22.5.303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharif M., Worrall J. G., Singh B., Gupta R. S., Lydyard P. M., Lambert C., McCulloch J., Rook G. A. The development of monoclonal antibodies to the human mitochondrial 60-kd heat-shock protein, and their use in studying the expression of the protein in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1992 Dec;35(12):1427–1433. doi: 10.1002/art.1780351205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith B. J., Yaffe M. P. A mutation in the yeast heat-shock factor gene causes temperature-sensitive defects in both mitochondrial protein import and the cell cycle. Mol Cell Biol. 1991 May;11(5):2647–2655. doi: 10.1128/mcb.11.5.2647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevenson M. A., Calderwood S. K. Members of the 70-kilodalton heat shock protein family contain a highly conserved calmodulin-binding domain. Mol Cell Biol. 1990 Mar;10(3):1234–1238. doi: 10.1128/mcb.10.3.1234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szekeres L., Papp J. G., Szilvássy Z., Udvary E., Vegh A. Moderate stress by cardiac pacing may induce both short term and long term cardioprotection. Cardiovasc Res. 1993 Apr;27(4):593–596. doi: 10.1093/cvr/27.4.593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welch W. J. Mammalian stress response: cell physiology, structure/function of stress proteins, and implications for medicine and disease. Physiol Rev. 1992 Oct;72(4):1063–1081. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1992.72.4.1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White F. P., White S. R. Isoproterenol induced myocardial necrosis is associated with stress protein synthesis in rat heart and thoracic aorta. Cardiovasc Res. 1986 Jul;20(7):512–515. doi: 10.1093/cvr/20.7.512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wier W. G., Yue D. T. Intracellular calcium transients underlying the short-term force-interval relationship in ferret ventricular myocardium. J Physiol. 1986 Jul;376:507–530. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1986.sp016167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wohlfart B. Relationships between peak force, action potential duration and stimulus interval in rabbit myocardium. Acta Physiol Scand. 1979 Aug;106(4):395–409. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.1979.tb06419.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Bilsen M., van der Vusse G. J., Snoeckx L. H., Arts T., Coumans W. A., Willemsen P. H., Reneman R. S. Effects of pyruvate on post-ischemic myocardial recovery at various workloads. Pflugers Arch. 1988 Dec;413(2):167–173. doi: 10.1007/BF00582527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]