Abstract

Purpose

The pressor effect of caffeine has been established in young men and premenopausal women. The effect of caffeine on blood pressure (BP) remains unknown in postmenopausal women and in relation to hormone replacement therapy (HRT) use.

Materials and Methods

In a randomized, 2-week cross-over design, we studied 165 healthy men and women in 6 groups: men and premenopausal women (35–-49 yrs) vs. men and postmenopausal women (50–-64 yrs), with postmenopausal women divided into those taking no hormone replacements (HR), estrogen alone, or estrogen and progesterone. Testing during one week of the study involved 6 days of caffeine maintenance at home (80 mg, 3x/day) followed by testing of responses to a challenge dose of caffeine (250 mg) in the laboratory. The other week involved ingesting placebos on maintenance and lab days. Resting BP responses to caffeine were measured at baseline and at 45 to 60 min following caffeine vs placebo ingestion, using automated monitors.

Results

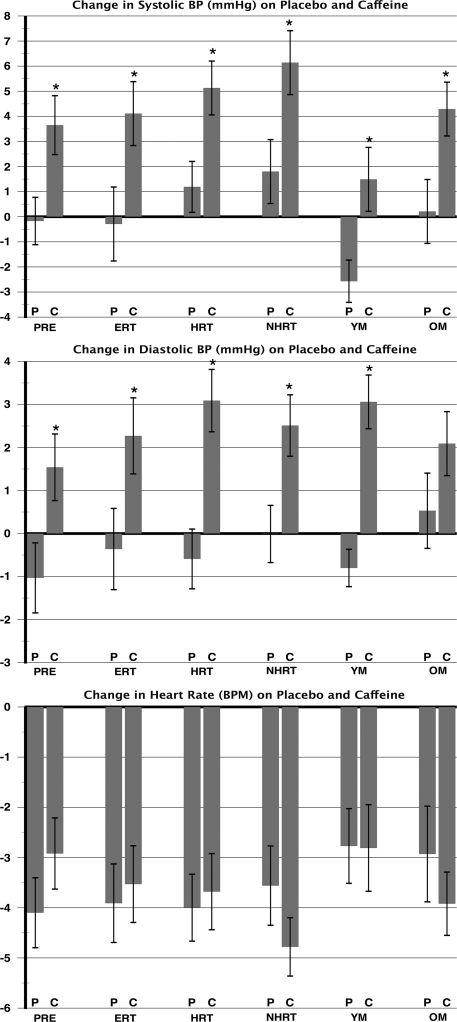

Ingestion of caffeine resulted in a significant increase in systolic BP in all 6 groups (4 ± .6, p < 0.01). Diastolic BP significantly increased in response to caffeine in all (3 ± .4, p < 0.04) but the group of older men (2 ± 1.0, p = 0.1). The observed pressor responses to caffeine did not vary by age.

Conclusions

Caffeine resulted in an increase in BP in healthy, normotensive, young and older men and women. This finding warrants the consideration of caffeine in the lifestyle interventions recommended for BP control across the age span.

Introduction

Caffeine is widely consumed by people of all ages. Men and women aged 35 to 64 yrs are among the highest consumers of caffeine,1 with an average intake of 250 mg/day, equivalent to 3 cups of brewed coffee. Because of its pervasive use, the effects of caffeine on the cardiovascular system should not be underestimated. The acute effect of caffeine on blood pressure (BP) is well documented, with increases in the range of 5 to 10 mmHg.2–5 In the laboratory setting, caffeine exerts its pressor effect through an increase in peripheral resistance in men and premenopausal women alike.6,7 Despite the popular belief that tolerance occurs with habitual consumption, numerous studies have demonstrated that tolerance to caffeine's pressor effects is incomplete following daily structured intake.8–10 Persistent increases in BP accompany caffeine ingestion, despite daily caffeine consumption in a large portion of caffeine consumers.9

Although BP responds acutely to caffeine in observational studies in and outside the lab. 8,10,11 epidemiological studies have usually revealed no association between reported coffee intake and chronic BP levels.12–15 In addressing this discrepancy between studies of acute administration and long-term BP regulation, we noted that the effects of caffeine are not well understood in specific subgroups. Larger increases in systolic and diastolic BPs were observed in response to caffeine in perimenopausal as compared to premenopausal women.16 This is not only triggered by the menopausal declines in ovarian hormone secretion17 but also by increasing age,18 higher body mass index (BMI),19 and changes in vascular compliance associated with menopause,20,21 which have been found to be associated with increased BP in the menopausal period, after controlling for ovarian hormone levels. Nevertheless, declines in ovarian hormone secretion are associated with increased BP.17 Thus, it is plausible that the presence of estrogen in normally cycling women may reduce the pressor effects of caffeine. Conversely, the lowering of estrogen levels in menopause might increase the effects of caffeine on BP. To our knowledge the pressor effects of caffeine have not been studied in postmenopausal women or classified according to hormone replacement therapy (HRT) use. Therefore we compared the effect of caffeine on BP in age-matched men and pre- and postmenopausal women, including those taking and not taking hormone replacements (HR). We hypothesized that men and postmenopausal women not taking HR would show the largest BP response to caffeine.

Materials and Methods

A total of 165 healthy men and women ages 35 to 64 yrs were recruited from the general populations of Buffalo, NY and Oklahoma City, OK. Subjects were stratified into 6 groups; men and premenopausal women (35–49 yrs) vs men and postmenopausal women (50–64 yrs), with postmenopausal women divided into those taking no hormone replacements (NHRT), estrogen alone (ERT), or estrogen and progesterone (HRT) (Table 1). All were nonsmokers, nonobese (BMI <30), and in good health by self-report and routine physical examination. Subjects were excluded if they had a history or displayed current evidence of heart disease, liver or renal disease, diabetes, severe asthma, or cerebrovascular disease. They had BP in the normotensive range (BP <135/85) at screening, regularly consumed 50 to 700 mg/day of caffeine by structured report, and used no prescription medications other than HRT in postmenopausal women. Subjects were screened for recent use of nonprescription medication and were instructed not to start any medications during the time they were enrolled in the study. Subjects were told to let us know if the need arose for the use of such medications, in which case their testing date was postponed. Premenopausal women were free from oral contraceptives and were not pregnant, as determined by urine pregnancy test (One Step Pregnancy Test, Inverness Medical Ltd., Beachwood Park, North Inverness, Scotland). Women were postmenopausal if they reported the absence of a menstrual period for the previous 12 months and had follicle stimulating hormone (FSH) levels in the postmenopausal range (>40 mIU/mL). Half of the subjects were tested in Buffalo, and half were tested in Oklahoma City. All participants signed a consent form approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Veterans Affairs Medical Center and the University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center in Oklahoma City, OK, and SUNY Buffalo, Buffalo, NY, and were paid for their participation.

Table 1.

Demographic and Baseline Differences by Group

| Variable Mean ± SE | ERT n = 25 | HRT n = 28 | NHRT n = 28 | PRE n = 28 | YM n = 28 | OM n = 28 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (yrs)* | 56 ± 0.78 | 57 ± 0.81 | 58 ± 0.76 | 42 ± 0.84 | 43 ± 0.98 | 56 ± 0.81 |

| BMI (kg/m2)* | 25.0 ± 0.54 | 24.9 ± 0.54 | 25.6 ± 0.51 | 25.0 ± 1.5 | 26.4 ± 0.41 | 25.8 ± 0.53 |

| FSH (mIU/ml)* | 43.9 ± 6.5 | 64.5 ± 4.7 | 72.3 ± 6.4 | 7.2 ± 1.1 | N/A | N/A |

| Caffeine intake (mg/day) | 342 ± 52 | 367 ± 43 | 393 ± 45 | 322 ± 46 | 371 ± 67 | 472 ± 52 |

| SBP (mmHg)* | 115 ± 2.8 | 110 ± 2.7 | 112 ± 2.8 | 105 ± 3.2 | 119 ± 3.2 | 118 ± 2.6 |

| DBP (mmHg)* | 67 ± 1.7 | 62 ± 1.7 | 65 ± 1.8 | 61 ± 2.1 | 73 ± 2.0 | 72 ± 1.6 |

| HR (beats/min) | 70 ± 1.9 | 68 ± 1.8 | 72 ± 1.9 | 66 ± 2.1 | 66 ± 2.2 | 66 ± 1.7 |

Significant group differences: *p < 0.05. Posthoc tests with Bonferroni corrections showed that for age, the PRE group differed from all groups except YM. For BMI, YM had a higher BMI than the PRE group. For SBP, premenopausal women had lower SBP than YM. For DBP, OM had higher DBP than PRE, HRT, and NHRT groups, whereas YM had higher DBP than PRE and HRT groups. BP and HR differences were adjusted for age.

SE, standard error; ERT, postmenopausal women taking estrogen therapy; HRT, postmenopausal women taking estrogen and progesterone therapy; NHRT, postmenopausal women not taking hormone replacement; PRE, premenopausal women; YM, young men; OM, older men; BMI, body mass index; FSH, follicle stimulating hormone; SBP, systolic blood pressure; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; HR, heart rate.

Study design, caffeine dosing, and compliance

In a randomized, 2-week crossover design, subjects consumed a placebo (3 inactive capsules) during home maintenance for 6 days and also consumed a placebo (1 inactive capsule) on day 7 in the lab. The other week involved ingestion of caffeine during home maintenance for 6 days (80 mg, 3x/day) and a 7th day of caffeine lab challenge (250 mg). The crossover conditions were counterbalanced. Home maintenance doses were supplied in bottles of identical gelatin capsules (College of Pharmacy, University of Oklahoma, Oklahoma City) containing either lactose or lactose mixed with 80 mg of U.S. Pharmacopeia (USP) caffeine (Professional Compounding Centers of America, Houston, TX). Subjects were instructed to eliminate all caffeine from their diet during the 2 weeks of the study. During home maintenance, subjects were instructed to take one capsule at 8:00 am, 1:00 pm, and 6:00 pm each day. Subjects were instructed to eliminate all caffeine from their diet during the 2 weeks of the study. Test day challenge doses were supplied in capsules containing either lactose or lactose mixed with 250 mg of USP caffeine (Gallipot, St. Paul, MN).

Lab protocol

The lab protocol included the following activities: breakfast that was designed to be consistent in nutritional value and quantity across test days, instrumentation for BP and heart rate (HR) measurement, a rest period (20 min), and predrug BP baseline (10 min), capsule, and postdrug response (60 min). BP was measured every 3 minutes during screenings and test sessions using a Dinamap 845 oscillometric vital signs monitor (Critikon, Tallahassee, FL). Compliance with home dosing was assessed by capsule counts, by caffeine assay of saliva specimens collected at home each day at 7:00 pm (Salivette®, Starstedt, Germany), and from a saliva specimen collected each morning upon entering the lab. Caffeine concentrations in saliva were measured by high performance liquid chromatography (Waters Corp., Milford, MA), following precipitation of proteins, using a methanol and water mobile phase and ultraviolet detection.22,23 Salivary caffeine concentrations are equivalent to those found in serum across a wide range of caffeine doses.24 Subjects found to be noncompliant by any of these criteria were dropped and replaced (n = 5).

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS (SPSS for Windows, rel. 12.0, SPSS, Chicago, IL). Baseline differences among groups were tested using the univariate analysis of variance (ANOVA), with posthoc comparisons using Holm's sequentially selective Bonferroni method. Age was adjusted for by using it as a covariate in the ANOVA models. Group differences in response to caffeine vs placebo were tested using ANOVA on each dependent variable in a 2 Drug × 2 Week × 6 Group design. Models were adjusted for age by using it as a covariate in the analyses. Significant main effects or interactions were followed by pairwise comparisons of response to caffeine vs response to placebo. Differences were deemed statistically significant if p < 0.05.

Results

Demographic and baseline differences by group

Table 1 presents the demographic, screening, and baseline data by group. Postmenopausal women had FSH values in the expected range. There were no significant group differences in habitual daily caffeine intake. All groups reported consuming caffeine equivalent to 3 to 4 cups of coffee/day in the diet. The sample was composed of a predominantly white population, and there were no significant differences in race across groups (χ2 = 41.2, p = 0.08). There were no differences in age among the 3 groups of postmenopausal women. Young men had the highest BMI compared to premenopausal women (F = 3.4, p = 0.006). There was a statistically significant overall group difference in systolic blood pressure (SBP); posthoc tests with corrections for multiple comparisons, adjusted for age, showed that premenopausal women had lower SBP compared to young men, with no significant differences among any of the other groups. On the other hand, older men had higher diastolic blood pressure (DBP) than women in the premenopausal, ERT, and HRT groups. Young men also had higher DBP than women in the premenopausal and HRT groups. There were no significant group differences in HR.

Effect of caffeine on BP

BP increased significantly following caffeine intake as compared to placebo (Week × drug interactions; SBP: F = 42.4, p < 0.0001 and DBP: F = 44.7, p < 0.0001). Pairwise contrasts of the change in BP after caffeine as compared to the change in BP after placebo revealed significant increases in SBP after caffeine compared to placebo in all 6 groups (Fig. 1). The DBP change after caffeine was significant in all groups except in the young men (p > 0.1). There were no significant differences in BP responses by HRT status, nor were there significant differences in HR responses to caffeine by group. Results of the repeated measures ANOVAs are displayed in Table 2. To distinguish the effects of age from that of hormonal status, we adjusted for age in the repeated measures analyses. There was no significant interaction effect of age with drug or week on SBP, DBP, or HR.

FIG. 1.

Change in blood pressure and heart rate in response to caffeine and placebo administration. BP, blood pressure; C, caffeine; P, placebo; PRE, premenopausal women; ERT, postmenopausal women taking estrogen therapy; HRT, postmenopausal women taking estrogen and progesterone therapy; NHRT, postmenopausal women not taking hormone replacement; YM, young men; OM, older men; BPM, beats per minute.

*Significant difference from placebo; responses per week, p < 0.05.

Table 2.

Summary of Repeated Measures ANOVAs (F-Values) for Week, Group, and Drug Manipulations

| Variablea | df | SBP | DBP | HR |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Week | 1,159 | 1.4 | 0.15 | 49.3* |

| Drug | 1,159 | 26.0* | 17.04* | 192.2* |

| Group | 1,159 | 6.3* | 12.34* | 0.91 |

| Week × group | 1,159 | 0.29 | 0.59 | 1.46 |

| Drug × group | 1,159 | 2.7* | 0.13 | 0.55 |

| Week × drug | 1,159 | 49.4* | 52.4* | 0.03 |

| Week × drug × group | 1,159 | 0.09 | 0.74 | 1.10 |

Week: placebo home maintenance vs caffeine home maintenance (80 mg/day for 6 days); drug: caffeine (250 mg) vs placebo administration in the laboratory; group: age, gender, and menopausal groups.

Significant F-values, p < 0.05.

ANOVA, analysis of variance; df, degrees of freedom; SBP, systolic blood pressure; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; HR, heart rate.

Discussion

The findings of this study confirm the expected pressor effects of caffeine and extend them across age and hormonal status groups. Caffeine ingestion (250 mg) resulted in average increases in SBP and DBP of 4 mmHg, compared to placebo, regardless of age, gender, menopausal, or hormonal status. This study was designed to closely mimic the effect of a morning caffeine dose in the regular consumer of caffeine. In previous studies by our group, a caffeine challenge was given after a week of placebo maintenance, thus maximizing caffeine's pressor effects.25 In this study, the caffeine challenge was given after a week of daily caffeine consumption. This pattern closely mimics actual caffeine consumption in the population, which increases the applicability of our findings. Moreover, our results demonstrate that a significant pressor response to caffeine persists despite daily consumption. It is commonly believed that daily caffeine consumption leads to pharmacologic tolerance, thus eliminating caffeine's pressor effect. However, this belief is not supported by findings from our laboratory8,9 or those of others.26 In a study of caffeine tolerance, we have demonstrated that in men and women aged 21 to 35 yrs persistent BP elevations occur both in laboratory and ambulatory settings, despite daily caffeine consumption.8,9

In this healthy nonhypertensive sample of men and women, caffeine's pressor effects did not vary by age, sex, or hormonal status. We had predicted that postmenopausal women not taking HR would potentially have larger BP responses to caffeine than their premenopausal counterparts. Premenopausal women have lower BP and greater vascular compliance than age-matched men27,28 and postmenopausal women.20 It might therefore be expected that premenopausal women would have negligible BP responses to caffeine. This was not the case in our study, where premenopausal women had significant elevations in BP in response to caffeine, despite their low resting baseline systolic and diastolic BP (104/61 mmHg). In addition, we expected postmenopausal women to have larger BP responses to caffeine compared to premenopausal women. In this sample, the BP responses of postmenopausal women were not significantly different from those of premenopausal women, regardless of hormone therapy (HT) use status. It has been suggested that the postmenopausal increase in BP is not because of the change in ovarian hormone levels but because of increasing age.18,29,30 Results have been contradictory, however, with some evidence that the increased BP associated with menopause is not explained by age.31–33 Controlling for age in our analyses did not change our findings. The present results therefore indicate that caffeine has consistent effects on BP in normotensive persons regardless of sex or hormonal status.

The pressor response to caffeine is greater in hypertensive and hypertension-prone subjects than in normotensive subjects.34 Unmedicated hypertensive patients have larger increases in diastolic BP after caffeine during exercise than do normotensive controls.35 Moreover, the pressor effects of caffeine are not diminished by the administration of antihypertensive medications.36 The magnitude of the pressor response observed in this study is of clinical significance, particularly if observed in hypertensive or borderline hypertensive subjects or in those otherwise at risk of developing hypertension. The pervasive consumption of caffeine across age groups and in practically all cultures makes its pressor effects of potential public health significance. The Hypertension Detection and Follow-up Program documented that a 5-mmHg reduction in BP was associated with a 20% reduction in 5-year mortality rates.37 Conversely, increases in BP of this magnitude, which are readily induced by caffeine consumption, may bear significant implications on morbidity and mortality. Despite the concern that caffeine might contribute to hypertension development, epidemiological studies have not found any consistent relationship between caffeine use and BP status. A possible reason for this set of inconsistent findings is that the population may vary in underlying responses to caffeine. Recent papers have identified an allelic variation in a gene controlling the cytochrome P450 metabolic pathway responsible for caffeine metabolism (CYP1A2 genotype). Persons possessing a slow metabolic profile, and consequently experiencing longer and greater caffeine exposure, have been shown to have a greater prevalence of hypertension38 and myocardial infarction39 associated with habitual caffeine intake with a graded dose-response effect. Thus, although caffeine acts acutely to increase BP, persons with impaired metabolism of caffeine and high levels of intake (>3 cups of coffee/day) may be at greater risk of negative cardiovascular consequences. The present study suggests that the pressor effects of caffeine, and the potential consequences of regular pressor episodes as seen here, are equal across sex, hormonal status, and age groups.

Conclusions

Caffeine consumption results in significant increases in BP in both laboratory and ambulatory settings8,9, the pressor effect is even larger in hypertensives,40 and the pressor effect is not diminished by chronic caffeine consumption.9,10 The present data indicate that caffeine produces increases in BP across age and gender groups. Future research should consider interventions to assess whether caffeine plays a role in BP regulation of uncontrolled hypertensive patients and whether lowering or eliminating caffeine intake would improve BP control in such patients.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NHLBI grant no. HL32050 and NIRR grant no. M01-RR14467 from the National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland. We gratefully acknowledge the efforts of Kathy Passanese and Bong Hee Sung for subject recruitment, testing, and data organization at SUNY Buffalo, New York.

Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Frary CD. Johnson RK. Wang MQ. Food sources and intakes of caffeine in the diets of persons in the United States. J Am Diet Assoc. 2005;105:110–103. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2004.10.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pincomb GA. Lovallo WR. Passey RB. Whitsett TL. Silverstein SM. Wilson MF. Effects of caffeine on vascular resistance, cardiac output and myocardial contractility in young men. Am J Cardiol. 1985;56:119–122. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(85)90578-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lovallo WR. Pincomb GA. Sung BH. Passey RB. Sausen KP. Wilson MF. Caffeine may potentiate adrenocortical stress responses in hypertension-prone men. Hypertension. 1989;14:170–176. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.14.2.170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lane JD. Caffeine and cardiovascular responses to stress. Psychosom Med. 1983;45:447–451. doi: 10.1097/00006842-198310000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.France C. Ditto B. Caffeine effects on several indices of cardiovascular activity at rest and during stress. J Behav Med. 1988;11:473–482. doi: 10.1007/BF00844840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Farag NH. Vincent AS. McKey BS. Whitsett TL. Lovallo WR. Hemodynamic mechanisms underlying the incomplete tolerance to caffeine's pressor effects. Am J Cardiol. 2005;95:1389–1392. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2005.01.093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.James JE. Gregg ME. Hemodynamic effects of dietary caffeine, sleep restriction, and laboratory stress. Psychophysiology. 2004;41:914–923. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.2004.00248.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Farag NH. Vincent AS. Sung BH. Whitsett TL. Wilson MF. Lovallo WR. Caffeine tolerance is incomplete: persistent blood pressure responses in the ambulatory setting. Am J Hypertens. 2005;18:714–719. doi: 10.1016/j.amjhyper.2005.03.738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lovallo WR. Wilson MF. Vincent AS. Sung BH. McKey BS. Whitsett TL. Blood pressure response to caffeine shows incomplete tolerance after short-term regular consumption. Hypertension. 2004;43:760–765. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000120965.63962.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.James JE. Chronic effects of habitual caffeine consumption on laboratory and ambulatory blood pressure levels. J Cardiovasc Risk. 1994;1:159–164. doi: 10.1177/174182679400100210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shepard JD. al'Absi M. Whitsett TL. Passey RB. Lovallo WR. Additive pressor effects of caffeine and stress in male medical students at risk for hypertension. Am J Hypertens. 2000;13:475–481. doi: 10.1016/s0895-7061(99)00217-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wilson PW. Garrison RJ. Kannel WB. McGee DL. Castelli WP. Is coffee consumption a contributor to cardiovascular disease? Insights from the Framingham study. Arch Intern Med. 1989;149:1169–1172. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Klatsky AL. Friedman GD. Armstrong MA. The relationships between alcoholic beverage use and other traits to blood pressure: a new Kaiser Permanente study. Circulation. 1986;73:628–636. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.73.4.628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Geleijnse JM. Habitual coffee consumption and blood pressure: an epidemiological perspective. Vasc Health Risk Manag. 2008;4:963–970. doi: 10.2147/vhrm.s3055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Noordzij M. Uiterwaal CS. Arends LR. Kok FJ. Grobbee DE. Geleijnse JM. Blood pressure response to chronic intake of coffee and caffeine: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Hypertens. 2005;23:921–928. doi: 10.1097/01.hjh.0000166828.94699.1d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Del Rio G. Menozzi R. Zizzo G. Avogaro A. Marrama P. Velardo A. Increased cardiovascular response to caffeine in perimenopausal women before and during estrogen therapy. Eur J Endocrinol. 1996;135:598–603. doi: 10.1530/eje.0.1350598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vongpatanasin W. Autonomic regulation of blood pressure in menopause. Semin Reprod Med. 2009;27:338–345. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1225262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Casiglia E. Tikhonoff V. Caffi S, et al. Menopause does not affect blood pressure and risk profile, and menopausal women do not become similar to men. J Hypertens. 2008;26:1983–1992. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e32830bfdd9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cifkova R. Pitha J. Lejskova M. Lanska V. Zecova S. Blood pressure around the menopause: a population study. J Hypertens. 2008;26:1976–1982. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e32830b895c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rajkumar C. Kingwell BA. Cameron JD, et al. Hormonal therapy increases arterial compliance in postmenopausal women. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1997;30:350–356. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(97)00191-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Waddell TK. Rajkumar C. Cameron JD. Jennings GL. Dart AM. Kingwell BA. Withdrawal of hormonal therapy for 4 weeks decreases arterial compliance in postmenopausal women. J Hypertens. 1999;17:413–418. doi: 10.1097/00004872-199917030-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Christensen HD. Whitsett TL. Measurements of xanthines and their metabolites by means of high pressure liquid chromatography. In: Hawk GL, editor. Biological/biomedical applications of liquid chromatography science. New York: Marcel Dekker; 1979. pp. 507–538. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Scott NR. Chakraborty J. Marks V. Determination of caffeine, theophylline and theobromine in serum and saliva using high-performance liquid chromatography. Ann Clin Biochem. 1984;21:120–124. doi: 10.1177/000456328402100208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee TC. Charles BG. Steer PA. Flenady VJ. Saliva as a valid alternative to serum in monitoring intravenous caffeine treatment for apnea of prematurity. Ther Drug Monit. 1996;18:288–293. doi: 10.1097/00007691-199606000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Farag NH. Vincent AS. McKey BS. Al'Absi M. Whitsett TL. Lovallo WR. Sex differences in the hemodynamic responses to mental stress: effect of caffeine consumption. Psychophysiology. 2006;43:337–343. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.2006.00416.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.James JE. Critical review of dietary caffeine and blood pressure: a relationship that should be taken more seriously. Psychosom Med. 2004;66:63–71. doi: 10.1097/10.psy.0000107884.78247.f9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Burt VL. Whelton P. Roccella EJ, et al. Prevalence of hypertension in the US adult population. Results from the third national health and nutrition examination survey, 1988–1991. Hypertension. 1995;25:305–313. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.25.3.305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wiinberg N. Hoegholm A. Christensen HR, et al. Twenty-four-hour ambulatory blood pressure in 352 normal Danish subjects, related to age and gender. Am J Hypertens. 995;8:978–986. doi: 10.1016/0895-7061(95)00216-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Casiglia E. d'Este D. Ginocchio G, et al. Lack of influence of menopause on blood pressure and cardiovascular risk profile: a 16-year longitudinal study concerning a cohort of 568 women. J Hypertens. 1996;14:729–736. doi: 10.1097/00004872-199606000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Portaluppi F. Pansini F. Manfredini R. Mollica G. Relative influence of menopausal status, age, and body mass index on blood pressure. Hypertension. 1997;29:976–979. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.29.4.976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Staessen J. Fagard R. Lijnen P. Amery A. [The influence of menopause on blood pressure] Arch Belg. 1989;47:118–122. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Staessen JA. Ginocchio G. Thijs L. Fagard R. Conventional and ambulatory blood pressure and menopause in a prospective population study. J Hum Hypertens. 1997;11:507–514. doi: 10.1038/sj.jhh.1000476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zanchetti A. Facchetti R. Cesana GC. Modena MG. Pirrelli A. Sega R. Menopause- related blood pressure increase and its relationship to age and body mass index: the SIMONA epidemiological study. J Hypertens. 2005;23:2269–2276. doi: 10.1097/01.hjh.0000194118.35098.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lovallo WR. Al'Absi M. Blick K. Whitsett TL. Wilson MF. Stress-like adrenocorticotropin responses to caffeine in young healthy men. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1996;55:365–369. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(96)00105-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sung BH. Lovallo WR. Pincomb GA. Wilson MF. Effects of caffeine on blood pressure response during exercise in normotensive healthy young men. Am J Cardiol. 1990;65:909–913. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(90)91435-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Smits P. Hoffmann H. Thien T. Houben H. van't Laar A. Hemodynamic and humoral effects of coffee after beta 1-selective and nonselective beta-blockade. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1983;34:153–158. doi: 10.1038/clpt.1983.145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.MacMahon S. Peto R. Cutler J, et al. Blood pressure, stroke, and coronary heart disease. Part 1: Prolonged differences in blood pressure: prospective observational studies corrected for the regression dilution bias. Lancet. 1990;335:765–774. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(90)90878-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Palatini P. Ceolotto G. Ragazzo F, et al. CYP1A2 genotype modifies the association between coffee intake and the risk of hypertension. J Hypertens. 2009;27:1594–1601. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e32832ba850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cornelis MC. El-Sohemy A. Kabagambe EK. Campos H. Coffee, CYP1A2 genotype, and risk of myocardial infarction. JAMA. 2006;295:1135–1141. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.10.1135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lovallo WR. Pincomb GA. Sung BH. Everson SA. Passey RB. Wilson MF. Hypertension risk and caffeine's effect on cardiovascular activity during mental stress in young men. Health Psychol. 1991;10:236–243. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.10.4.236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]