Abstract

In addition to playing a cardinal role in androgen production, LH also regulates growth and proliferation of theca-interstitial (T-I) cells. Here, we show for the first time that LH/human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) regulates T-I cell proliferation via the mammalian target of rapamycin complex 1 (mTORC1) signaling network. LH/hCG treatment showed a time-dependent stimulation of T-I cell proliferation and phosphorylation of protein kinase B (AKT), ERK1/2, and ribosomal protein (rp)S6 kinase 1 (S6K1), and its downstream effector, rpS6. Pharmacological inhibition of ERK1/2 signaling did not block the hCG-induced phosphorylation of tuberin, the upstream regulator of mTORC1 or S6K1, the downstream target of mTORC1. However, inhibition of AKT signaling completely blocked the hCG response. Furthermore, the AKT-specific inhibitor abolished forskolin (FSK)-stimulated phosphorylation of AKT, tuberin, S6K1, and rpS6. Human CG and FSK-mediated phosphorylation of AKT and downstream targets of mTORC1 were attenuated by inhibition of adenylyl cyclase. Pharmacologic targeting of mTORC1 with rapamycin also abrogated hCG or FSK-induced phosphorylation of S6K1, rpS6, and eukaryotic initiation factor 4E binding protein 1. In addition, hCG or FSK-mediated up-regulation of the cell cycle regulatory proteins cyclin-dependent kinase 4, cyclin D3, and proliferating cell nuclear antigen was blocked by rapamycin. These results were further confirmed by demonstrating that knockdown of mTORC1 using small interfering RNA abolished hCG-mediated increases in cell proliferation and the expression of cyclin D3 and proliferating cell nuclear antigen. Taken together, the present studies show a novel intracellular signaling pathway for T-I cell proliferation involving LH/hCG-mediated activation of the AKT/mTORC1 signaling cascade.

LH regulates the expression of cell cycle regulatory proteins in theca-interstitial cells through activation of PI3-kinase/AKT/mTORC1 signaling cascade.

Theca-interstitial (T-I) cells in the ovary secrete androgens, which are then converted to estrogens by the granulosa cells in the follicles (1,2). The synthesis of androgen by T-I cells is primarily regulated by LH, which, upon binding to the LH receptor, promotes increased steroid production through activation of a cAMP-dependent signal transduction cascade (3). Abnormal function of T-I cells has been shown to be associated with pathological conditions, such as polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS). The theca cells of the polycystic ovary produce high amounts of androgens, leading to anovulation (4,5). In most instances, the hypersecretion of androgens is associated with elevated levels of LH and insulin, and these conditions lead to increased T-I cell size and number (6), supporting the concept that ovarian hyperandrogenism is associated with an increased number of androgen-producing cells contributing to increased androgen production (7,8,9).

A growing body of evidence suggests that G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) activate multiple signaling pathways in steroidogenic cells (10,11,12,13,14,15). For example, FSH activates protein kinase B (AKT) downstream of phosphatidylinositol 3 kinase (PI3K) and MAPK pathways in granulosa cells (15,16,17,18). Furthermore, LH-mediated ERK activation has been shown to play a pivotal role in the regulation of steroidogenesis in bovine theca cells (19). LH has also been reported to stimulate the PI3K/AKT pathway in rat ovary (20). Because AKT has been identified as the upstream activator of mammalian target of rapamycin complex 1 (mTORC1), in the present study, we sought to determine whether the growth regulatory function of LH/human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) in T-I cells is mediated by the mTORC1 signaling pathway. Here, we provide evidence for the first time that LH/hCG can activate mTORC1 signaling by the AKT-dependent pathway and that mTORC1-mediated signaling plays a crucial role in hCG-induced T-I cell proliferation by up-regulating cyclin-dependent kinase 4 (CDK4), cyclin D3, and proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA) expression.

Results

HCG enhances cell proliferation and cyclin D1 and cyclin D3 mRNA expression

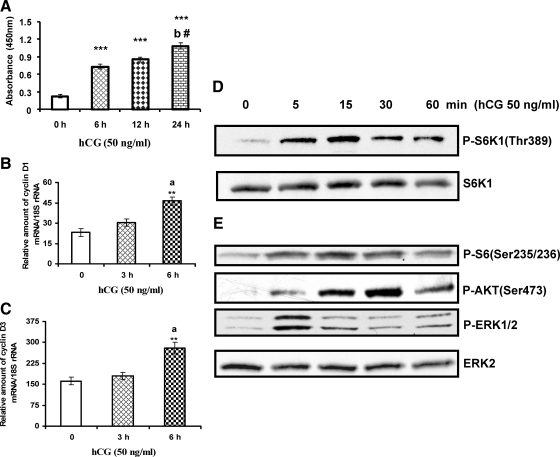

Cultured T-I cells isolated from immature rat ovaries were treated with hCG (50 ng/ml) for 0, 6, 12, and 24 h in the presence of bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU). The proliferation was assessed by BrdU incorporation as described in Materials and Methods. The results presented in Fig. 1A show that hCG promotes the incorporation of BrdU into newly synthesized DNA in T-I cells in a time-dependent manner, suggesting that LH/hCG stimulates T-I cell proliferation.

Figure 1.

Time-course study of hCG effect on cell proliferation, cyclin D1 and cyclin D3 mRNA expression, and phosphorylation (P) of S6K1, rpS6, AKT, and ERK1/2. Ovaries were collected from 25-d-old Sprague-Dawley rats. T-I cells were isolated by collagenase digestion, and cells were plated with McCoy’s medium. After a 24-h attachment, cells were treated with hCG (50 ng/ml) for different time periods. A, Cell proliferation was assessed by BrdU incorporation after 0, 6, 12, and 24 h. B and C, Total RNA was reverse-transcribed, and the resulting cDNA was subjected to real-time PCR using predesigned primers and probes for rat cyclin D1 and cyclin D3 as described in Materials and Methods. The graph in B shows changes in cyclin D1 mRNA expression normalized for 18S rRNA. The graph in C shows changes in cyclin D3 mRNA expression normalized for 18S rRNA. D and E, Cells were lysed using radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer and subjected to Western blot analysis using phospho-specific S6K1 (Thr389) antibody (D) and phospho-specific rpS6 (Ser235/236), phospho-AKT (Ser473), and phospho-ERK1/2 antibodies (E). The levels of S6K1 or ERK2 proteins were used as loading controls. Error bars represent mean ± se of three independent experiments, triplicate determinations in each. **, P < 0.01 and ***, P < 0.001 vs. control. a, Significant differences (P < 0.05) compared with 3-h hCG treatment; b and #, significant differences (P < 0.01 and P < 0.05) compared with hCG 6- and 12-h treatment, respectively. Blots in each panel are representative of three separate experiments.

Because hCG promotes cell proliferation, we next examined whether there is a difference in the pattern of cyclin D1 and cyclin D3 mRNA expression in response to hCG treatment, because D-type cyclins are components of the cell cycle machinery and govern progression through G1 phase in response to extracellular signals. Cyclin D1 and cyclin D3 mRNA have been shown predominantly in the T-I cells by in situ hybridization (21). In our experiments, cells were treated with hCG (50 ng/ml) for 0, 3, and 6 h. Total RNA was extracted, and the mRNA levels of cyclin D1 and cyclin D3 were determined by quantitative PCR. The results presented in Fig. 1, B and C, show a significant increase in mRNA levels of cyclin D1 and cyclin D3 in response to hCG treatment for 6 h. These results indicate that hCG stimulates mRNA expression of the cell cycle regulatory proteins cyclin D1 and cyclin D3.

HCG stimulates activation of ribosomal protein (rp)S6 kinase 1 (S6K1) and rpS6

mTOR is a Ser-Thr kinase that belongs to the phosphoinositide 3-kinase-related kinase family. It consists of two distinct multiprotein complexes, mTORC1 and mTORC2 (22). mTORC1 positively regulates cell growth and proliferation. Because hCG promotes T-I cell proliferation and cyclin D1 and cyclin D3 mRNA expression, we examined the effect of hCG on S6K1 phosphorylation, because S6K1 is a downstream target of mTORC1 signaling. To test this, T-I cells were cultured with hCG (50 ng/ml) for different time intervals, and the phosphorylation of S6K1 was examined by Western blot analysis using a phospho-specific antibody that recognizes S6K1 phosphorylated at Thr389. The results show that within 5 min of hCG addition, S6K1 is robustly phosphorylated at Thr389, reaching maximal phosphorylation at 15 min (Fig. 1D). S6K1 is known to phosphorylate S6, a protein associated with ribosomal subunits that enables association of polyribosomes with mRNAs (23,24,25,26,27,28,29). To further confirm the functional significance of S6K1 activation by hCG, Western blot analysis was performed with phospho-specific antibody for rpS6 Ser 235/236. The results show that hCG treatment increases the phosphorylation of rpS6, the downstream target of S6K1 (Fig. 1E). These results established that hCG activates mTORC1 signaling in T-I cells.

To examine further the signaling pathways through which hCG stimulates S6K1, we assessed the upstream molecules of mTORC1 that are responsive to hCG treatment. Because GPCRs have been shown to activate multiple signaling pathways (10,11,12,13,14,15), the effect of hCG on the phosphorylation of AKT and ERK1/2 was tested. To investigate this, cultured cells were treated with hCG for different time periods. The presence of phospho-AKT was analyzed by immunoblot using an antibody specific for AKT phosphorylated at Ser473. The results show that the increase in AKT phosphorylation occurs rapidly by 15 min and is further augmented 30 min after hCG treatment. At 60 min, the extent of AKT phosphorylation is lower than that seen at 30 min. ERK1/2 phosphorylation is increased within 5 min after hCG (Fig. 1E). These results indicate that hCG treatment induces phosphorylation of both AKT as well as ERK1/2 in these cells.

Human CG stimulates tuberin (TSC2) phosphorylation and activation of S6K1 through an AKT-dependent pathway

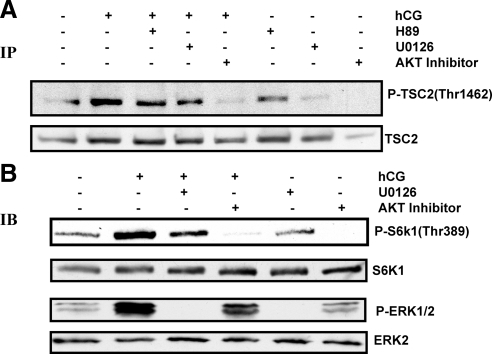

Because hCG treatment is known to activate the protein kinase A (PKA), ERK1/2, and AKT signaling pathways, pharmacological inhibitors of these pathways were used to determine the signaling pathway involved in hCG-mediated phosphorylation of TSC2, a known upstream regulator of mTORC1. AKT phosphorylation of TSC2 at Thr1462 has been shown to reverse its inhibitory effect on mTORC1 signaling (30,31,32). To examine this, cells were preincubated with PKA inhibitor (H89, 10 μm) or MAPK kinase (MEK) inhibitor (U0126, 10 μm) for 1 h or AKT-specific inhibitor (AKT inhibitor VIII, 5 μm) for 15 min, followed by stimulation with hCG for 15 min. Total TSC2 was immunoprecipitated from cell lysates, and Western blot analysis was performed using a TCS2 Thr1462 phospho-specific antibody. The results demonstrate that inhibition of PKA or MAPK pathway does not completely suppress TSC2 phosphorylation, whereas inhibition of AKT abolishes TSC2 phosphorylation (Fig. 2A). The inability of H89 to block TSC2 phosphorylation is consistent with the previous studies of Alam et al. (13), who showed that H89 failed to inhibit FSH and forskolin (FSK)-mediated phosphorylation of AKT and TSC2. Our results suggest that hCG-mediated activation of mTORC1 signaling occurs through the AKT-dependent pathway.

Figure 2.

Effect of PKA, MEK 1, and AKT inhibition on hCG-stimulated phosphorylation (P) of TSC2, S6K1, and ERK1/2. Cells were pretreated without or with 10 μm PKA inhibitor (H89) or MEK inhibitor (U0126) for 1 h or 5 μm AKT inhibitor VIII for 15 min, followed by hCG (50 ng/ml) treatment for 15 min. Control groups were treated with vehicle (dimethylsulfoxide). Total TSC2 was immunoprecipitated from the cell lysates, and Western blot analysis was performed using phospho-specific TSC2 (Thr1462). TSC2 protein expression served as an internal control (A). For B, cells were preincubated with MEK inhibitor or AKT inhibitor followed by hCG treatment for 15 min. The cell lysates were examined for phospho-specific S6K1 (Thr389) and phospho-ERK1/2 by Western blot analysis. Protein loading was monitored by stripping and reprobing the same blot with S6K1 and ERK2 antibodies. Results in each panel are representative of three separate experiments. IP, Immunoprecipitation; IB, immunoblot.

The effect of MEK and AKT inhibitors was also tested on the downstream targets of mTORC1 activation in response to hCG. T-I cells were preincubated with MEK inhibitor (U0126, 10 μm) for 1 h or AKT-specific inhibitor (AKT inhibitor VIII, 5 μm) for 15 min followed by hCG treatment for 15 min. The cell lysates were analyzed for S6K1Thr389 phosphorylation. The results presented in Fig. 2B show that, although the MEK inhibitor caused partial inhibition of S6K1 phosphorylation, the AKT inhibitor produced complete inhibition.

The inhibitory potential of MEK inhibitor was assessed by examining the phosphorylation of ERK1/2 under hCG-stimulated conditions. Figure 2B shows that treatment with hCG resulted in a robust elevation of ERK1/2 phosphorylation. Pretreatment with MEK inhibitor (U0126, 10 μm) abolished the hCG-mediated phosphorylation of ERK1/2. By contrast, pretreatment with AKT specific inhibitor (AKT inhibitor VIII, 5 μm) slightly reduced the phosphorylation of ERK1/2 in response to hCG. Taken together, these results suggest that, although hCG stimulates both AKT and ERK1/2 signaling, hCG-mediated mTORC1 activation is selectively regulated by an AKT-dependent signaling pathway and is independent of the ERK1/2 activation.

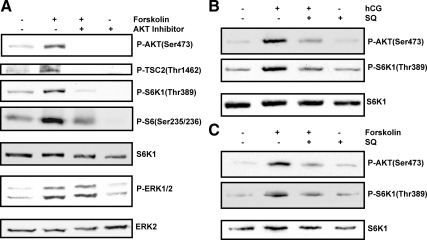

Phosphorylation of AKT, TSC2, S6K1, and rpS6 through cAMP-dependent activation of PI3K

Because LH/hCG is known to increase cAMP production, we sought to determine whether the effect of hCG on mTORC1 signaling pathway is mimicked by the pharmacological adenylate cyclase activator, FSK. To test this, cultured T-I cells were treated with FSK (10 μm) for 15 min. A second group of cultures was pretreated for 15 min with AKT-specific inhibitor (AKT inhibitor VIII, 5 μm) before incubation with FSK. The cell lysates were then examined for phospho-specific AKT, ERK1/2, TSC2, and downstream targets of mTORC1. As expected, FSK treatment increased the phosphorylation of AKT Ser473, TSC2 Thr1462, S6K1Thr389, and rpS6 Ser235/236, whereas pretreatment with AKT inhibitor abolished this activation, as shown in Fig. 3A. However, pretreatment with AKT inhibitor did not affect the FSK-mediated phosphorylation of ERK1/2. These results further confirm the involvement of the AKT-dependent phosphorylation of TSC2 and the activation of mTORC1 signaling in response to LH/hCG.

Figure 3.

Effect of AKT and adenylyl cyclase inhibitors on hCG and FSK-stimulated phosphorylation (P) of AKT and downstream targets of mTORC1. A, Cells were pretreated without or with AKT inhibitor VIII (5 μm) for 15 min followed by FSK (10 μm) treatment for 15 min. Control groups were treated with vehicle (dimethylsulfoxide). The cell lysates were then analyzed for phospho-specific AKT (Ser473), TSC2 (Thr1462), S6K1 (Thr389), rpS6 (Ser235/236), and ERK1/2 by Western blotting. B and C, Cells were pretreated without or with adenylyl cyclase inhibitor, SQ22536 (50 μm) for 30 min followed by hCG (B) or FSK (C) for another 15 min, and phosphorylation of AKT (Ser473) and S6K1 (Thr389) was examined by immunoblot analysis. Equal loading was monitored by stripping and reprobing the same blot with S6K1 or ERK2 antibodies. Results in each panel are representative of three separate experiments.

To provide further evidence for the involvement of cAMP in the activation of PI3K and mTORC1 signaling, we used a pharmacological adenylate cyclase inhibitor, SQ 22536, which is known to inhibit cAMP production. T-I cells were pretreated without or with adenylate cyclase inhibitor (SQ 22536, 50 μm) for 30 min followed by the addition of hCG or FSK for another 15 min. The cell lysates were analyzed for phosphorylation of AKT and downstream targets of mTORC1. The results presented in Fig. 3, B and C, show that hCG (B) and FSK (C) stimulated AKT Ser473 and S6K1Thr389 phosphorylation, whereas pretreatment with adenylate cyclase inhibitor attenuated this response. These results provide additional evidence that hCG-mediated activation of AKT and mTORC1 signaling proceed through cAMP-mediated activation of the PI3K/AKT/mTORC1 signaling cascade.

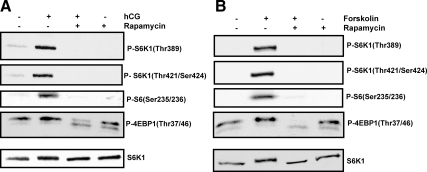

HCG or FSK-stimulated S6K1, rpS6, and eukaryotic initiation factor 4E binding protein 1 (4EBP-1) phosphorylation is sensitive to rapamycin

For the next set of experiments, we used the mTORC1 antagonist, rapamycin, to further validate that phosphorylation of S6K1 and 4EBP-1 occurs downstream of mTORC1 activation in hCG or FSK-stimulated cells. T-I cells were pretreated with mTORC1 inhibitor (rapamycin 20 nm) for 1 h followed by hCG or FSK for 15 min. Immunoblot analysis was performed using phospho-specific S6K1 Thr389, S6K1 Thr421/Ser424, rpS6 Ser235/236, and 4EBP-1 Thr37/46 antibodies. The results show that activation of the downstream effectors of mTORC1 in response to hCG or FSK was blocked by treatment with the mTORC1 inhibitor, rapamycin (Fig. 4, A and B).

Figure 4.

Effect of rapamycin on hCG and FSK-stimulated phosphorylation (P) of S6K1, rpS6, and 4EBP-1. A, T-I cells were pretreated without or with rapamycin (20 nm) for 1 h before treatment for 15 min with hCG (50 ng/ml). Control groups were treated with vehicle (dimethylsulfoxide). Cells were lysed and subjected to Western blot analysis using phosphorylation site-specific antibodies for S6K1 (Thr389), S6K1 (Thr421/Ser424), rpS6 (Ser235/236), and 4EBP-1(Thr37/46). B, Cells were pretreated with rapamycin (20 nm) for 1 h followed by FSK (10 μm) treatment for 15 min. Western blot analysis was performed using the above indicated phosphorylation site-specific antibodies. The levels of S6K1 protein were used as internal controls. Results in each panel are representative of three separate experiments.

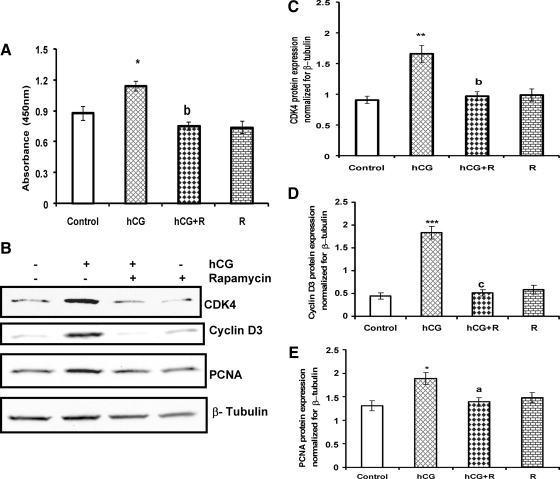

Human CG-induced T-I cell proliferation and cell cycle regulatory protein expression are rapamycin sensitive

The role of mTORC1 signaling in cell proliferation was examined by treating T-I cells with rapamycin (20 nm) for 1 h followed by hCG for 24 h in the presence of BrdU. The results presented in Fig. 5A show that hCG treatment increased BrdU incorporation, and this stimulatory effect was abrogated by the addition of the mTORC1 inhibitor, rapamycin. These results suggest that LH/hCG-stimulated cell proliferation occurs through the mTORC1-dependent signaling pathway.

Figure 5.

Effect of mTORC1 inhibition on hCG-stimulated cell proliferation and cell cycle regulatory protein expression. A, Cells were incubated with mTORC1 inhibitor (rapamycin, 20 nm) for 1 h followed by hCG treatment for 24 h. Control groups received vehicle (dimethylsulfoxide). Cells were labeled with BrdU, and cell proliferation was assessed by BrdU incorporation as described in Materials and Methods. B, Cells were pretreated without or with rapamycin (20 nm) for 1 h before treatment for 24 h with hCG (50 ng/ml). The cell lysates were analyzed by Western blotting for CDK4, cyclin D3 and PCNA, and for β-tubulin to verify equal protein loading. The graphs (C–E) represent densitrometric scans of CDK4, cyclin D3, and PCNA protein expression normalized for β-tubulin as seen in B. Blots are representative of one experiment, and the graphs represent the mean of three experiments. Error bars represent mean ± se. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; and ***, P < 0.001 vs. control. a–c, Significant differences (P < 0.05, P < 0.01, and P < 0.001, respectively) compared with hCG treatment. R, Rapamycin.

Cell cycle progression from G1 to the S phase is regulated by D-type cyclins, which modulate the activities of the cyclin-dependent kinases. Furthermore, rapamycin has been reported to block cell cycle progression at the G1 to S phase in a number of cell types (33,34,35,36). To determine the effect of rapamycin on cyclin D1 mRNA expression, T-I cells were preincubated with rapamycin (20 nm) for 1 h followed by the addition of hCG for 6 h. Total RNA was extracted, and the mRNA levels of cyclin D1 were determined by real-time PCR. The results indicate that hCG-stimulated cyclin D1 mRNA expression was reduced by addition of rapamycin (Supplemental Fig. 1, published on The Endocrine Society’s Journals Online web site at http://mend.endojournals.org).

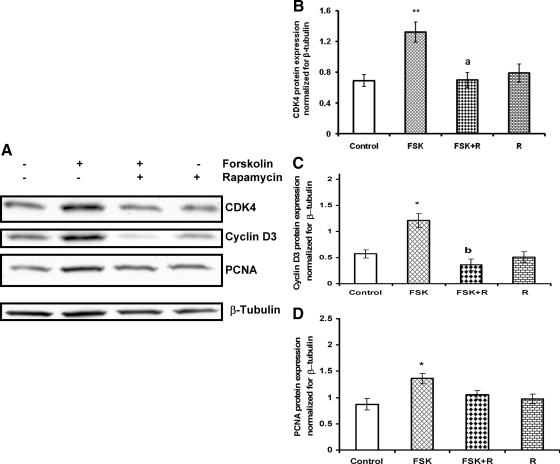

The effect of mTORC1 blockade on the expression of other cell cycle regulatory proteins was then examined. Cells were preincubated with the mTORC1 inhibitor rapamycin (20 nm) for 1 h, followed by hCG or FSK stimulation for 24 h. The cell lysates were examined for the cell cycle regulatory proteins CDK4, cyclin D3, and PCNA by Western blot analysis. The results demonstrated that, although hCG or FSK treatment alone caused significant increases in the expression of the cell cycle regulatory proteins (Figs. 5B and 6A, respectively), the addition of rapamycin strongly inhibited these increases, suggesting that hCG or FSK-stimulated cell cycle regulatory protein expression occurs through the mTORC1-dependent pathway (Figs. 5 and 6, respectively). Furthermore, we also examined the phosphorylation levels of AKT and downstream target of mTORC1 at 24-h treatment with hCG. The results show that the stimulatory effect on phosphorylation of AKT Ser473 and S6K1 Thr389 was also seen after 24 h exposure to hCG (Supplemental Fig. 2), although the extent of phosphorylation was lower at longer time periods when compared with that seen at 15-min hCG treatment (our unpublished data).

Figure 6.

Effect of rapamycin on FSK-stimulated cell cycle regulatory protein expression. A, Cells were pretreated without or with rapamycin (20 nm) for 1 h followed by FSK (10 μm) treatment for 24 h. Control groups were treated with vehicle (dimethylsulfoxide). The cell lysates were examined for CDK4, cyclin D3, and PCNA protein expression by Western blot analysis. The level of β-tubulin was used as loading control. The graphs (B–D) represent densitrometric scans of CDK4, cyclin D3, and PCNA protein expression normalized for β-tubulin. Blots are representative of one experiment, and the graphs represent the mean of three experiments. Error bars represent mean ± se. *, P < 0.05 and **, P < 0.01 vs. control. a and b, Significant differences (P < 0.05 and P< 0.01, respectively) compared with FSK treatment. R, Rapamycin.

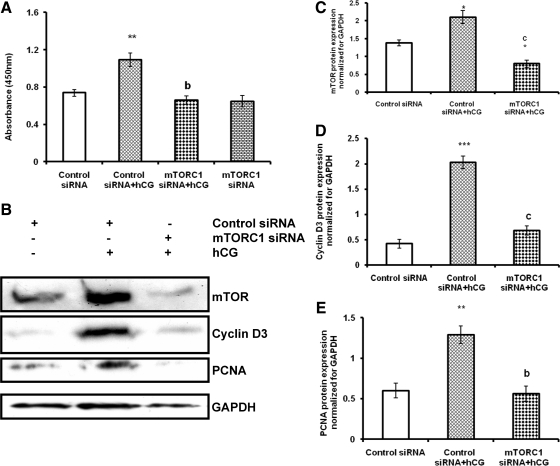

Small interfering RNA (siRNA)-mediated silencing of mTORC1 and its effect on cell proliferation and cell cycle regulatory proteins expression

To provide further evidence of mTORC1-mediated regulation of cell proliferation and cell cycle regulatory protein expression, T-I cells were transfected with mTORC1 siRNA to knockdown mTORC1 expression. To assess transfection efficiency, initial experiments were performed with green fluorescence protein vector transfection by electroporation. The transfection efficiency with green fluorescence protein was greater than 50% (Supplemental Fig. 3). After optimizing transfection efficiency, cells were transfected with control siRNA or mTORC1 siRNA for 48 h followed by hCG treatment for 24 h in the presence of BrdU. The results show that, as expected, hCG induces cell proliferation, whereas siRNA-mediated knockdown of mTORC1 significantly reduced the response to hCG (Fig. 7A). These results provide additional evidence that hCG-mediated activation of mTORC1 is necessary for T-I cell proliferation.

Figure 7.

mTORC1 siRNA inhibits hCG-induced cell proliferation and cell cycle regulatory protein expression. A, T-I cells were transfected with 100 nm of control siRNA or mTORC1 siRNA for 48 h and then labeled with BrdU in the presence or absence of hCG for 24 h. The cell proliferation was assessed by BrdU incorporation as described in Materials and Methods. B, Cells were transfected with control siRNA or mTORC1 siRNA for 48 h and then treated without or with hCG for another 24 h. Proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE (4–20%) and then immunoblotted with mTOR, cyclin D3, or PCNA antibodies. Protein loading was monitored by stripping and reprobing the same blot with antibody for GAPDH. The graphs (C–E) represent densitrometric scans of mTOR, cyclin D3, and PCNA protein expression normalized for GAPDH. Blots are representative of one experiment, and the graphs represent the mean of three experiments. Error bars represent mean ± se. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; and ***, P < 0.001 vs. control siRNA. b and c, Significant differences (P < 0.01 and P < 0.001, respectively) compared with control siRNA plus hCG treatment.

To determine whether siRNA-mediated silencing of mTORC1 inhibits cell cycle regulatory protein expression, cells were transfected with control siRNA or mTORC1 siRNA for 48 h followed by hCG treatment for 24 h. Cell lysates were analyzed for mTOR and cell cycle regulatory proteins by Western blot analysis. As shown in Fig. 7B, the level of mTOR expression was repressed in hCG-treated cells transfected with the siRNA targeting mTORC1, compared with hCG-treated cells with nontargeting siRNA or cells transfected with control siRNA alone. Furthermore, the knockdown of mTORC1 by mTORC1 siRNA abrogated hCG-induced cyclin D3 and PCNA protein expression. These results conclusively show that mTORC1 signaling plays an important role in hCG-mediated regulation of cell proliferative markers.

Discussion

An increase in theca cell number and size is seen in pathological conditions, such as PCOS, which is the most common cause of infertility in women. The present studies provide new insights into the intracellular signaling cascade by which LH/hCG induces T-I cell proliferation. We show that activation of the LH/hCG receptor, a member of the GPCR family, is capable of cross talk with the PI3K/AKT pathway to activate mTORC1 signaling and stimulation of the proliferation cascade. Treatment with hCG or FSK leads to increased phosphorylation of AKT, TSC2, and activation of mTORC1 signaling. The activation of the downstream targets of mTORC1, S6K1, and 4EBP-1 in response to hCG or FSK treatment was abrogated by the mTORC1 inhibitor, rapamycin. Furthermore, LH/hCG-induced increases in cell proliferation and cell cycle regulatory proteins were abolished by treatment with rapamycin or siRNA-mediated knockdown of mTORC1.

Although the activation of the mTORC1 signaling pathway in response to growth factors has been established, the novelty of the present study is that this pathway is also engaged by ligands that stimulate the GPCR signaling pathway in T-I cells. It is now established that PI3K/AKT-mediated activation of mTORC1 signaling involves the participation of the tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC) (TSC1-TSC2) that functions downstream of AKT and upstream of mTORC1 to restrict cell growth and proliferation (37,38,39,40). The activation of AKT, the upstream regulator of mTORC1, by hCG or FSK resulted in inhibiting the activity of the tumor suppressor protein, TSC2 by phosphorylating at the Thr1462 residue, leading to activation of the mTORC1 signaling cascade. The finding that hCG or FSK treatment increased TSC2 phosphorylation at the Thr1462 residue and that the AKT inhibitor abolished this response, supports the notion that hCG stimulates TSC2 phosphorylation through an AKT-dependent pathway. The present findings are consistent with previous studies showing that AKT phosphorylation was up-regulated in the theca cells of PCOS ovaries and that AKT phosphorylation was further augmented by insulin treatment (41). AKT phosphorylation of TSC2 leads to a functional inactivation of the TSC1-TSC2 complex and results in mTORC1 activation, leading to phosphorylation of downstream targets S6K1 and 4EBP-1 and activation of mRNA translation (42,43,44). It has been shown that the activation of S6K1 stimulates translation and growth by phosphorylating rpS6 (44,45,46,47,48,49) and that the mitogenic stimulation of cells correlates with phosphorylation of S6K1 and rpS6 (50,51,52). The finding that treatment with hCG resulted in rapid phosphorylation of S6K1 and rpS6, and that this response was completely blocked by AKT inhibitor and by rapamycin, suggests that hCG-mediated phosphorylation and activation of PI3K/AKT and mTORC1 are necessary for its growth-promoting effect in T-I cells. Furthermore, hCG or FSK-induced phosphorylation of AKT and downstream target of mTORC1 is abrogated by adenylyl cyclase inhibitor, suggesting that cAMP plays a central role in this process.

Human CG treatment also induced 4EBP-1 phosphorylation. 4EBP-1, another well-characterized mTORC1 target, is a translational repressor, binding to the translation initiation factor 4E (eIF4E), which recognizes the 5′ cap of eukaryotic mRNA (24,45). Upon phosphorylation, 4EBP-1 releases from eIF4E, allowing eIF4E to assemble with other translation initiation factors to initiate cap-dependent translation. The mTORC1 pathway plays a key role in hypertrophic-hyperplasic growth and acts as a central regulator of protein synthesis and ribosome biogenesis by acting at transcriptional and translational levels (46,53). Because treatment with rapamycin abolished hCG and FSK-mediated S6K1/S6 and 4EBP-1 phosphorylation and also blocked cell cycle regulatory protein expression, our data therefore suggest that the downstream targets of mTORC1, S6K1/S6, and eIF4E participate in hCG-induced cell cycle regulatory protein expression in T-I cells. Thus, on the basis of our present findings, we speculate that the increases in T-I cell mass seen under pathological conditions, such as PCOS, might occur through overexpression of this pathway. Additionally, our results show that LH/hCG and FSK-mediated T-I cell proliferative markers are regulated by mTORC1-dependent increases in CDK4, cyclin D3, and PCNA expression. This is supported by the demonstration that suppression of mTORC1 by the pharmacological inhibitor, rapamycin, and the siRNA-mediated knockdown of mTORC1 reduced cell proliferation and expression of cell cycle regulatory proteins. Therefore, the reduction of cell cycle regulatory protein expression by rapamycin treatment or through siRNA-mediated knockdown of mTORC1 is supportive of a role for mTORC1 signaling in LH/hCG-induced T-I cell proliferation.

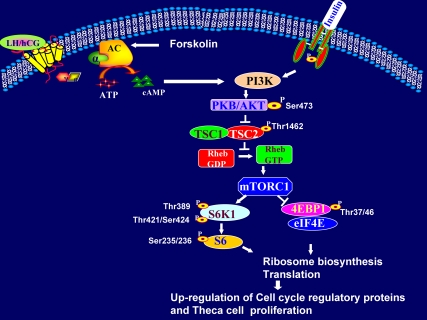

In summary, our results provide a novel intracellular signaling pathway, by which LH/hCG-mediated activation of cAMP/ PI3K/AKT/ mTORC1 cascade plays an essential role in T-I cell proliferation by up-regulating cell cycle regulatory proteins as shown in Fig. 8. Furthermore, the present findings extend our understanding of the intracellular signal diversity elicited by LH/hCG in target cells.

Figure 8.

A schematic model of LH/hCG-mediated mTORC1 signaling in T-I cells. The results of the present study support the schematic model in which LH/hCG signal triggers cAMP production, leading to activation of PI3K to promote AKT phosphorylation. This leads to inactivation of TSC2 by phosphorylating the Thr1462 residue and consequently the activation of mTORC1 signaling. mTORC1 enhances the phosphorylation of 4EBP-1 and S6K1, which activates the rpS6 and consequently increases the translational machinery. The cell cycle regulatory proteins CDK4, cyclin D3, and PCNA are up-regulated via increased translation. An increase in cell cycle regulatory proteins leads to theca cell proliferation.

Materials and Methods

Medium 199, McCoy’s 5A medium, l-glutamine, and HEPES buffer were purchased from Invitrogen/GIBCO (Carlsbad, CA). Penicillin-streptomycin was purchased from Roche Diagnostics (Indianapolis, IN). Collagenase (CLS I) and deoxyribonuclease I were obtained from Worthington Biochemical Corp. (Freehold, NJ). BSA and β-tubulin antibody were purchased from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, MO). Purified hCG was purchased from A. F. Parlow (Torrance, CA). FSK and SQ 22536 were obtained from BIOMOL Research Laboratories (Plymouth Meeting, PA). mTORC1 inhibitor, rapamycin, and antibodies against phosphorylated AKT (Ser473), phospho-TSC2 (Thr1462), phospho-S6K1 (Thr389), phosphorylated S6K1 (Thr421/Ser424), S6K1, phospho-4EBP-1 (Thr37/46), phosphorylated rpS6 (Ser235/236), cyclin D3, CDK4, and the mTOR siRNA kit were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Beverly, MA). Antibodies against TSC2, ERK2, PCNA, and phosphorylated ERK1/2 were obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc. (Santa Cruz, CA). Antiglyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) was obtained from Chemicon (Temecula, CA). Protein A and G agarose beads were purchased from Upstate Cell Signaling Solutions (Lake Placid, NY). MEK inhibitor U0126 was obtained from Promega (Madison, WI) and AKT inhibitor VIII and H89 were from Calbiochem (La Jolla, CA). Antimouse, antirabbit IgG horseradish peroxidase conjugates, enhanced chemiluminescence using the Femto Supersignal Substrate System and Restore Western blot stripping buffer were purchased from Pierce (Rockford, IL). Reagents, as well as the primers and probes for cyclin D1 and cyclin D3 mRNA, were from Applied Biosystems (Foster City, CA). All other reagents used were conventional commercial products.

Animals

Sprague-Dawley female rats (25 d old) were purchased from Charles River Laboratories (Wilmington, MA). All the experimental protocols used in this study were approved by the University Committee on the Use and Care of Animals. Animals were housed in a temperature-controlled room with proper dark-light cycles as per the guidelines provided by the University Committee on the Use and Care of Animals. The animals were killed by CO2 asphyxiation. The ovaries were removed under sterile conditions and were processed immediately for the isolation of T-I cells.

Isolation and culture of T-I cells

The T-I cells were isolated, dispersed, and cultured following a protocol previously published from our laboratory (54,55). Briefly, freshly collected ovaries were placed in medium 199 containing 25 mm HEPES (pH 7.4), 2 mm l-glutamine, 1 mg/ml BSA, 100 U/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin. The ovaries were then freed from adhering fat and actively punctured with a 27-gauge needle under a dissecting microscope to release the granulosa and blood cells. The remaining ovarian tissue was then washed three times with medium to release any remaining granulosa cells. The tissue was then minced and incubated for 30 min at 37 C in the same medium, supplemented with 0.65 mg/ml collagenase type 1 plus 10 μg/ml deoxyribonuclease. The dispersion was encouraged by mechanically pipetting the ovarian tissue suspension with a 10-ml pipette. The T-I cells released by this digestion were centrifuged at 250 g for 5 min and washed in medium two times to eliminate remaining collagenase. The dispersed cells were then resuspended in McCoy’s 5A medium containing 2 mm l-glutamine, 1 mg/ml BSA, 100 U/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin and subjected to unit gravity sedimentation for 5 min to eliminate small fragments of undispersed ovarian tissue. Cell viability was assessed by trypan blue exclusion and was always above 90%. The dispersed cells were seeded in 60-mm plates (3 × 106 viable cells). The plated cells were maintained overnight in McCoy’s 5A medium containing 2 mm l-glutamine, 1 mg/ml BSA, 100 U/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin in a humidified atmosphere of 95% air-5% CO2 at 37 C. After allowing cells to attach, they were treated with hCG for different time intervals, and inhibitors were used as indicated in the figure legends.

BrdU cell proliferation assay

Cell proliferation was evaluated by measuring the incorporation of BrdU using BrdU immunoassay kits (Calbiochem). In brief, T-I cells were seeded into 96-well plates and cultured overnight with 0.1% BSA-containing McCoy’s medium. After attachment, cells were treated with hCG (50 ng/ml) for 0, 6, 12, and 24 h or pretreated with rapamycin for 1 h followed by hCG treatment for 24 h. Cells were labeled with BrdU during the above treatment periods. For experiments examining siRNA-mediated silencing of mTORC1 and its effect on hCG-induced cell proliferation, T-I cells were transfected with control siRNA (nontargeted) or mTORC1 siRNA (targeted) using a Nucleofector transfection reagent (Amaxa, Cologne, Germany), as per the manufacturer’s instructions. After transfection, cells were resuspended in 5% fetal bovine serum/McCoy’s medium and plated. Forty-eight hours later, the media were replaced with serum-free media for overnight culture and then labeled with BrdU and treated without or with hCG (50 ng/ml) for an additional 24 h. The reactions were terminated by removing the media, and cells were incubated with fixative/denaturing solution followed by BrdU antibody for 1 h at room temperature. Unbound antibody was washed, and then horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat antimouse IgG was added for 30 min at room temperature. After washing three times, substrate was added and incubated in the dark for 15 min. The plates were read using a spectrophotometric plate reader.

Real-time PCR

To examine the effect of hCG on cyclin D1 and cyclin D3 mRNA expression, cultured T-I cells were exposed to hCG (50 ng/ml) for 0, 3, and 6 h. The role of mTORC1 in hCG-mediated cyclin D1 mRNA expression was examined by pretreating the cells with or without rapamycin (20 nm) for 1 h, followed by hCG for 6 h. At the end of incubation, the cells were harvested, and total RNA was extracted using TRIzol reagent following the manufacturer’s instructions (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA). Aliquots of total RNA (50 ng) extracted from the control and treated groups were reverse-transcribed in a reaction volume of 20 μl using 2.5 μm random hexamer, 500 μm deoxynucleotide triphosphates, 5.5 mm MgCl2, 8 U ribonuclease inhibitor, and 25 U MultiScribe reverse transcriptase. The reactions were carried out in a PTC-100 (MJ Research, Watertown, MA) thermal controller (25 C for10 min, 48 C for 30 min, and 95 C for 5 min). The resulting cDNAs were diluted with water. The real-time PCR quantification was then performed using 5 μl of the diluted cDNAs in triplicate with predesigned primers and probes for rat cyclin D1 and cyclin D3 (TaqMan Assay on Demand Gene Expression products; Applied Biosystems). Reactions were carried out in a final volume of 25 μl using an Applied Biosystems 7300 real-time PCR system (95 C for 15 sec, 60 C for 1 min) after initial incubation for 10 min at 95 C. The changes in cyclin D1 and cyclin D3 expression were calculated using the standard curve method with 18S rRNA as the internal control.

Western blot analysis

After various treatments described in the respective figure legends, cell monolayers were washed with PBS and then were solubilized using radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer (PBS containing 1% Nonidet P-40, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, and 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate). Cell lysates were then sonicated and centrifuged for 10 min at 13,000 × g. The protein content of the supernatants was determined using BCA reagent (Pierce). Proteins (50 μg/lane) were separated by electrophoresis using 10% SDS-PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) before immunoblot analysis. Membranes were blocked in 5% fat-free milk in 20 mm Tris base (pH 7.45), 137 mm NaCl, and 0.1% Tween 20 (TBST) for 1 h at room temperature and then incubated overnight at 4 C with primary antibody in 5% fat-free milk/TBST. After three 5-min washes with TBST, membranes were incubated in appropriate horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies for 1 h at room temperature. After three 5-min washes with TBST, membrane-bound antibodies were detected with the Femto Supersignal Substrate System Western blotting detection kit (Pierce). Protein loading was monitored by reprobing the same blots with appropriate antibodies (loading control) as indicated in the figure legends.

Immunoprecipitation for TCS2

To study the effect of PKA, ERK, and AKT inhibition on hCG-stimulated phosphorylation of TSC2 (Thr1462), cultured T-I cells were preincubated with PKA inhibitor H89 (10 μm) or MEK inhibitor U0126 (10 μm) for 1 h and AKT inhibitor VIII (5 μm) for 15 min. These preincubations were followed by hCG (50 ng/ml) treatment for 15 min. Reactions were stopped by removing the media, and cells were lysed in 0.5 ml of lysis buffer [10 mm Tris (pH 7.5), 100 mm Nacl, 1% Nonidet P-40, 2 mm EDTA, 50 mm NaF, and protease inhibitors]. After centrifugation, supernatants were collected, and TSC2 was immunoprecipitated from lysates overnight at 4 C in a final volume of 500 μl containing anti-TSC2 antibody (1:100) and then incubated with protein A/G agarose beads (1:1) for additional 3 h at 4 C. Beads were washed four times with lysis buffer, and the immune complexes were boiled in 2× sample buffer and fractionated on 7.5% SDS-PAGEs.

siRNA-mediated silencing of mTORC1

T-I cells were transfected with control siRNA (nontargeted) or mTORC1 siRNA (targeted) using a Nucleofector transfection reagent (Amaxa), as per the manufacturer’s instructions. After transfection, cells were resuspended in 5% fetal bovine serum/McCoy’s medium and plated. Forty-eight hours later, media were replaced with serum-free medium for overnight culture and then treated without or with hCG (50 ng/ml) for an additional 24 h. mTOR, cyclin D3, and PCNA were measured by Western blot analysis using mTOR, cyclin D3, and PCNA antibodies.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was carried out using one-way ANOVA followed by the Tukey multiple comparison test using Prism software (GraphPad Prism, version 3.0; GraphPad, Inc., San Diego, CA). Values were considered statistically significant at P < 0.05. Each experiment was repeated at least three times, with similar results. Blots are representative of one experiment, and graphs represent the mean ± se of three replicates.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Helle Peegel, Dr. Pradeep Kayampilly, Dr. Bindu Menon, and Dr. Thippeswamy Gulappa for their critical reading of the manuscript and valuable comments.

Footnotes

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health Grant HD 38424.

Disclosure Summary: The authors have nothing to disclose.

First Published Online July 21, 2010

Abbreviations: AKT, Protein kinase B; BrdU, bromodeoxyuridine; CDK4, cyclin-dependent kinase 4; 4EBP-1, eukaryotic initiation factor 4E binding protein 1; eIF4E, translation initiation factor 4E; FSK, forskolin; GAPDH, antiglyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase; GPCR, G protein-coupled receptor; hCG, human chorionic gonadotropin; MEK, MAPK kinase; mTORC1, mammalian target of rapamycin complex 1; PCNA, proliferating cell nuclear antigen; PCOS, polycystic ovarian syndrome; PI3K, phosphatidylinositol 3 kinase; PKA, protein kinase A; rp, ribosomal protein; siRNA, small interfering RNA; S6K1, rpS6 kinase 1; TBST, Tris-buffered saline with Tween 20; T-I, theca-interstitial; TSC2, tuberin; TSC, tuberous sclerosis complex.

References

- Magoffin DA 2002 The ovarian androgen-producing cells: a 2001 perspective. Rev Endocr Metab Disord 3:47–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magoffin DA 2005 Ovarian theca cell. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 37:1344–1349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leung PC, Steele GL 1992 Intracellular signaling in the gonads. Endocr Rev 13:476–498 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duleba AJ, Foyouzi N, Karaca M, Pehlivan T, Kwintkiewicz J, Behrman HR 2004 Proliferation of ovarian theca-interstitial cells is modulated by antioxidants and oxidative stress. Hum Reprod 19:1519–1524 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spaczynski RZ, Tilly JL, Mansour A, Duleba AJ 2005 Insulin and insulin-like growth factors inhibit and luteinizing hormone augments ovarian theca-interstitial cell apoptosis. Mol Hum Reprod 11:319–324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jakimiuk AJ, Weitsman SR, Navab A, Magoffin DA 2001 Luteinizing hormone receptor, steroidogenesis acute regulatory protein, and steroidogenic enzyme messenger ribonucleic acids are overexpressed in thecal and granulosa cells from polycystic ovaries. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 86:1318–1323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magoffin DA 2006 Ovarian enzyme activities in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Fertil Steril 86(Suppl 1):S9–S11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franks S 1995 Polycystic ovary syndrome. N Engl J Med 333:853–861 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azziz R 2003 Androgen excess is the key element in polycystic ovary syndrome. Fertil Steril 80:252–254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richards JS 2001 New signaling pathways for hormones and cyclic adenosine 3′,5′- monophosphate action in endocrine cells. Mol Endocrinol 15:209–218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood JR, Strauss 3rd JF 2002 Multiple signal transduction pathways regulate ovarian steroidogenesis. Rev Endocr Metab Disord 3:33–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunzicker-Dunn M, Maizels ET 2006 FSH signaling pathways in immature granulosa cells that regulate target gene expression: branching out from protein kinase A. Cell Signal 18:1351–1359 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alam H, Maizels ET, Park Y, Ghaey S, Feiger ZJ, Chandel NS, Hunzicker-Dunn M 2004 Follicle-stimulating hormone activation of hypoxia-inducible factor-1 by the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/AKT/Ras homolog enriched in brain (Rheb)/mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) pathway is necessary for induction of select protein markers of follicular differentiation. J Biol Chem 279:19431–19440 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arvisais EW, Romanelli A, Hou X, Davis JS 2006 AKT-independent phosphorylation of TSC2 and activation of mTOR and ribosomal protein S6 kinase signaling by prostaglandin F2α. J Biol Chem 281:26904–26913 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kayampilly PP, Menon KMJ 2007 Follicle-stimulating hormone increases tuberin phosphorylation and mammalian target of rapamycin signaling through an extracellular signal-regulated kinase-dependent pathway in rat granulosa cells. Endocrinology 148:3950–3957 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Robayna IJ, Falender AE, Ochsner S, Firestone GL, Richards JS 2000 Follicle-Stimulating hormone (FSH) stimulates phosphorylation and activation of protein kinase B (PKB/AKT) and serum and glucocorticoid-lnduced kinase (Sgk): evidence for A kinase-independent signaling by FSH in granulosa cells. Mol Endocrinol 14:1283–1300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeleznik AJ, Saxena D, Little-Ihrig L 2003 Protein kinase B is obligatory for follicle-stimulating hormone-induced granulosa cell differentiation. Endocrinology 144:3985–3994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andric N, Ascoli M 2006 A delayed gonadotropin-dependent and growth factor-mediated activation of the extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 cascade negatively regulates aromatase expression in granulosa cells. Mol Endocrinol 20:3308–3320 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tajima K, Yoshii K, Fukuda S, Orisaka M, Miyamoto K, Amsterdam A, Kotsuji F 2005 Luteinizing hormone-induced extracellular-signal regulated kinase activation differently modulates progesterone and androstenedione production in bovine theca cells. Endocrinology 146:2903–2910 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho CR, Carvalheira JB, Lima MH, Zimmerman SF, Caperuto LC, Amanso A, Gasparetti AL, Meneghetti V, Zimmerman LF, Velloso LA, Saad MJ 2003 Novel signal transduction pathway for luteinizing hormone and its interaction with insulin: activation of Janus kinase/signal transducer and activator of transcription and phosphoinositol 3-kinase/AKT pathways. Endocrinology 144:638–647 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robker RL, Richards JS 1998 Hormone-induced proliferation and differentiation of granulosa cells: a coordinated balance of the cell cycle regulators cyclin D2 and p27Kip1. Mol Endocrinol 12: 924–940 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guertin DA, Sabatini DM 2007 Defining the role of mTOR in cancer. Cancer Cell 12:9–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoki K, Ouyang H, Li Y, Guan KL 2005 Signaling by target of rapamycin proteins in cell growth control. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 69:79–100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tee AR, Blenis J 2005 mTOR, translational control and human disease. Semin Cell Dev Biol 16:29–37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma XM, Blenis J 2009 Molecular mechanisms of mTOR-mediated translational control. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 10:307–318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fingar DC, Salama S, Tsou C, Harlow E, Blenis J 2002 Mammalian cell size is controlled by mTOR and its downstream targets S6K1 and 4EBP1/eIF4E. Genes Dev 16:1472–1487 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruvinsky I, Meyuhas O 2006 Ribosomal protein S6 phosphorylation: from protein synthesis to cell size. Trends Biochem Sci 31:342–348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hay N, Sonenberg N 2004 Upstream and downstream of mTOR. Genes Dev 18:1926–1945 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson CJ, Schalm SS, Blenis J 2004 PI3-kinase and TOR: PIKTORing cell growth. Semin Cell Dev Biol 15:147–159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tee AR, Fingar DC, Manning BD, Kwiatkowski DJ, Cantley LC, Blenis J 2002 Tuberous sclerosis complex-1 and -2 gene products function together to inhibit mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR)-mediated downstream signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 99:13571–13576 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manning BD, Cantley LC 2003 United at last: the tuberous sclerosis complex gene products connect the phosphoinositide 3-kinase/AKT pathway to mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) signalling. Biochem Soc Trans 31:573–578 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoki K, Corradetti MN, Guan KL 2005 Dysregulation of the TSC-mTOR pathway in human disease. Nat Genet 37:19–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nourse J, Firpo E, Flanagan WM, Coats S, Polyak K, Lee MH, Massague J, Crabtree GR, Roberts JM 1994 Interleukin-2-mediated elimination of the p27Kip1 cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor prevented by rapamycin. Nature 372 :570–573 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Withers DJ, Seufferlein T, Mann D, Garcia B, Jones N, Rozengurt E 1997 Rapamycin dissociates p70(S6K) activation from DNA synthesis stimulated by bombesin and insulin in Swiss 3T3 cells. J Biol Chem 272:2509–25014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Y, Chen SY, Ross KN, Balk SP 2006 Androgens induce prostate cancer cell proliferation through mammalian target of rapamycin activation and post-transcriptional increases in cyclin D proteins. Cancer Res 66:7783–7792 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fingar DC, Blenis J 2004 Target of rapamycin (TOR): an integrator of nutrient and growth factor signals and coordinator of cell growth and cell cycle progression. Oncogene 23:3151–3171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao X, Zhang Y, Arrazola P, Hino O, Kobayashi T, Yeung RS, Ru B, Pan D, Gao X, Zhang Y, Arrazola P, Hino O, Kobayashi T, Yeung RS, Ru B, Pan D 2002 Tsc tumour suppressor proteins antagonize amino-acid-TOR signalling. Nat Cell Biol 4:699–704 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goncharova EA, Goncharov DA, Eszterhas A, Hunter DS, Glassberg MK, Yeung RS, Walker CL, Noonan D, Kwiatkowski DJ, Chou MM, Panettieri Jr RA, Krymskaya VP 2002 Tuberin regulates p70 S6 kinase activation and ribosomal protein S6 phosphorylation. A role for the TSC2 tumor suppressor gene in pulmonary lymphangioleiomyomatosis (LAM). J Biol Chem 277:30958–30967 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwiatkowski DJ, Zhang H, Bandura JL, Heiberger KM, Glogauer M, el-Hashemite N, Onda H 2002 A mouse model of TSC1 reveals sex-dependent lethality from liver hemangiomas, and up-regulation of p70S6 kinase activity in Tsc1 null cells. Hum Mol Genet 11:525–534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tee AR, Fingar DC, Manning BD, Kwiatkowski DJ, Cantley LC, Blenis J 2002 Tuberous sclerosis complex-1 and -2 gene products function together to inhibit mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR)-mediated downstream signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 99:13571–13576 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood JR, Nelson-Degrave VL, Jansen E, McAllister JM, Mosselman S, Strauss 3rd JF 2005 Valproate-induced alterations in human theca cell gene expression: clues to the association between valproate use and metabolic side effects. Physiol Genomics 20:233–243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoki K, Li Y, Zhu T, Wu J, Guan KL 2002 TSC2 is phosphorylated and inhibited by AKT and suppresses mTOR signalling. Nat Cell Biol 4:648–657 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manning BD, Tee AR, Logsdon MN, Blenis J, Cantley LC 2002 Identification of the tuberous sclerosis complex-2 tumor suppressor gene product tuberin as a target of the phosphoinositide 3-kinase/AKT pathway. Mol Cell 10:151–162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potter CJ, Pedraza LG, Xu T 2002 AKT regulates growth by directly phosphorylating Tsc2. Nat Cell Biol 4:658–665 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fingar DC, Richardson CJ, Tee AR, Cheatham L, Tsou C, Blenis J 2004 mTOR controls cell cycle progression through its cell growth effectors S6K1 and 4E-BP1/eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4E. Mol Cell Biol 24:200–216 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fingar DC, Salama S, Tsou C, Harlow E, Blenis J 2002 Mammalian cell size is controlled by mTOR and its downstream targets S6K1 and 4EBP1/eIF4E. Genes Dev 16:1472–1487 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tee AR, Blenis J, Proud CG 2005 Analysis of mTOR signaling by the small G-proteins, Rheb and RhebL1. FEBS Lett 579:4763–4768 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmelzle T, Hall MN 2000 TOR, a central controller of cell growth. Cell. 103:253–262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wullschleger S, Loewith R, Hall MN 2006 TOR signaling in growth and metabolism. Cell 124:471–484 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruvinsky I, Meyuhas O 2006 Ribosomal protein S6 phosphorylation: from protein synthesis to cell size. Trends Biochem Sci 31:342–348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandi HR, Ferrari S, Krieg J, Meyer HE, Thomas G 1993 Identification of 40 S ribosomal protein S6 phosphorylation sites in Swiss mouse 3T3 fibroblasts stimulated with serum.J Biol Chem 268:4530–4533 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou MM, Blenis J 1995 The 70 kDa S6 kinase: regulation of a kinase with multiple roles in mitogenic signaling. Curr Opin Cell Biol 7:806–814 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas G 2002 The S6 kinase signaling pathway in the control of development and growth. Biol Res 35:305–313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palaniappan M, Menon KMJ 2009 Regulation of sterol regulatory element binding transcription factor 1a by human chorionic gonadotropin and insulin in cultured rat theca-interstitial cells. Biol Reprod 81:284–292 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Q, Sucheta S, Azhar S, Menon KMJ 2003 Lipoprotein enhancement of ovarian theca-interstitial cell steroidogenesis: relative contribution of scavenger receptor class B (type I) and adenosine 5′-triphosphate- binding cassette (type A1) transporter in high-density lipoprotein-cholesterol transport and androgen synthesis. Endocrinology 144:2437–2445 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.