Abstract

Gliomas are among the most devastating adult tumors for which there is currently no cure. The tumors are derived from brain glial tissue and comprise several diverse tumor forms and grades. Recent reports highlight the importance of cancer-initiating cells in the malignancy of gliomas. These cells have been referred to as brain cancer stem cells (bCSC), as they share similarities to normal neural stem cells in the brain. The Notch signaling pathway is involved in cell fate decisions throughout normal development and in stem cell proliferation and maintenance. The role of Notch in cancer is now firmly established, and recent data implicate a role for Notch signaling also in gliomas and bCSC. In this review, we explore the role of the Notch signaling pathway in gliomas with emphasis on its role in normal brain development and its interplay with pathways and processes that are characteristic of malignant gliomas.

Keywords: angiogenesis, cancer stem cells, EGFR, glioma, Notch

Gliomas are one of the most lethal and treatment resistant types of human adult cancer. The tumors are thought to be derived from glial tissue and comprise ependymomas, oligodendrogliomas, and astrocytomas. Astrocytomas are further divided into grades I–IV of which grade I tumor are the least aggressive and grade IV tumors, glioblastoma multiforme (GBM), the most aggressive. GBM can arise either de novo (primary GBM) or develop from a pre-existing low-grade tumor (secondary GBM). Treatment of brain cancer is a considerable therapeutic challenge, and although patients with low-grade gliomas can survive for years, patients with GBM survive only for 1–2 years after diagnosis.1 Recently, a population of cells, capable of clonal growth in vitro and tumor formation in vivo, has been identified in gliomas.2,3 These cells are defined as brain cancer stem cells (bCSC) as they show profound similarity to normal neural stem cells (NSC). It has been hypothesized that these cells are involved in brain tumor progression, resistance to treatment, and ultimately tumor relapse.4

The Notch signaling pathway is involved in cell fate decisions during normal development and in the genesis of several cancers.5,6 The downstream effects of Notch signaling are highly tissue and time dependent, and Notch has been implicated both in the maintenance of neural progenitors and in the generation of glia during development of the brain.7 Furthermore, the Notch signaling pathway are known to be involved in the cellular response to hypoxia and angiogenesis,8,9 two processes that are characteristic of human gliomas, and especially GBM.10

In this review, we will first give an overview of the Notch signaling pathway and its involvement in cell fate decisions during development of the central nervous system (CNS). Then we will focus on the functional role of Notch signaling in human gliomas, with specific emphasis on astrocytomas and features such as growth factor signaling, bCSC, hypoxia, and angiogenesis, and possible ways of targeting this pathway for glioma therapy.

Notch Signaling Pathway

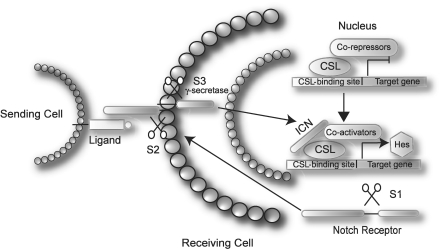

The Notch proteins (Notch 1–4) are transmembrane receptors produced as long polypeptides that are modified by several proteolytic cleavages before activation. The first cleavage, S1, occurs in the Golgi apparatus and is thought to be effected by a furin-like convertase.11 This generates a 180-kDa fragment containing most of the extracellular domain and a 120-kDa fragment corresponding to the transmembrane domain extending into the cytoplasm. The fragments stay noncovalently bound to each other and are inserted into the cell membrane as heterodimers (Fig. 1).12 Upon binding of ligand (i.e., Delta-like [Dll]-1, -3, and -4, and Jagged-1 and -2),13–17 a second cleavage, S2, takes place in the extracellular domain in close proximity to the cell membrane.18 This cleavage is performed by a member of the a disintegrin and metalloprotease domain (ADAM) family of metalloproteases called TACE (tumor necrosis factor-α converting enzyme, also known as ADAM17) and is believed to be required for exposure of the S3 activating cleavage site.19 The S3 activating cleavage is performed by the so-called γ-secretase complex.20 This releases the intracellular domain of Notch (ICN), which translocates to the nucleus and associates with the DNA-binding protein CSL (CBF, suppressor of hairless, LAG-1; also referred to as RBP-Jκ).21 In the absence of ICN, CSL interacts with corepressor complexes and functions as a transcriptional repressor.22 Once bound to CSL, ICN promotes dissociation of the corepressor complexes in favor of a transcriptional activating complex,23 thereby converting CSL from a transcriptional repressor to an activator.

Fig. 1.

Schematic overview of the canonical Notch signaling pathway. The Notch receptors are produced as large proteins that are cleaved (S1) and inserted in the membrane as heterodimers. Upon ligand binding, two consecutive cleavages occur (S2 and S3), which release the ICN. In the nucleus, ICN forms a multimeric protein complex together with CSL and co-activators, and initiates transcription of target genes. See text for further details.

Among the best characterized transcriptional targets of Notch signaling are proteins belonging to the Hairy/Enhancer of split (Hes-1 to -7) and Hey (Hey-1, -2, -L; also published as Hrt-1, -2, -3; Hesr-1, -2, -3; Herp-2, -1, -3; Chf-2, -1; or Gridlock) families of basic helix-loop-helix (bHLH) transcriptional repressors.24 A number of studies have suggested that Hes-1, -5, -7 and Hey-1, -2, -L are direct targets of Notch signaling.24 Both Hes and Hey proteins are involved in transcriptional repression, and it has been shown that they regulate the expression and the function of pro-neuronal bHLH proteins such as mammalian achaete-scute homologue-1 (Mash-1, Hash-1 in humans) and homologues of the Drosophila melanogaster atonal genes (eg, Math and Neurogenin).25

There is accumulating evidence for Notch signaling occurring through CSL but independently of Hes and Hey. Here, it is also worth mentioning cyclinD1,26 p21,27 and glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP),28 all of which contain CSL sites in their promoter regions. Furthermore, Notch signaling that is independent of CSL has also been reported.29

Notch Function in Cell Type Specification in the Brain

Notch has been associated with undifferentiated cells of the embryonic CNS, whereas its expression is reduced in the adult.30 In the CNS, Notch signaling is thought to maintain a pool of undifferentiated progenitors by inhibiting neuronal commitment and differentiation into neurons.31 The process by which Notch inhibits cells from adapting to a default cell fate, that is, maintaining a pool of multipotent progenitor cells, is called lateral inhibition; this process has been extensively studied in the peripheral nervous system of flies and vulva of worms.31 In this model, it has been suggested that Notch signaling occurs between adjacent cells in an initially homogenous progenitor pool expressing both Notch receptors and ligands. Stochastic events lead to increased ligand levels on one cell that activate Notch signaling in its neighbors. As Notch signaling is inhibitory for ligand expression in that same cell, initially small differences in receptor/ligand expression are amplified and one cell becomes signal sending (ie, ligand expressing) and the other one signal receiving (ie, receptor expressing). In the scenario of neural development, the signal-sending cell will differentiate into a neuronal precursor cell, whereas the signal receiving, and thus Notch-expressing cell, will stay as an uncommitted progenitor.30,31

It has recently been shown that Notch activation in some situations promotes a particular cell fate. As such, Notch has been assigned a role in inductive signaling, instructing cells toward a specific cell fate. This has been proposed to be the case in the differentiation of certain types of glia such as radial glia and astrocytes,32,33 whereas differentiation toward oligodendrocytes seems to be inhibited by Notch activation.34

Notch and Cancer

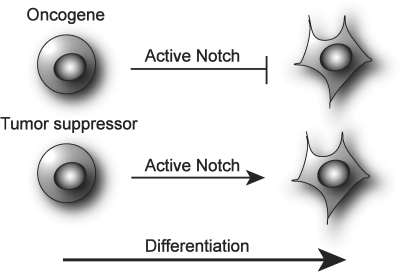

The outcome of Notch signaling in cancer is thought to reflect its role in normal development of a specific tissue/organ. In tissues, where Notch maintains a proliferative (Prol) precursor pool, and in which Notch activity has to be down-regulated in order for the cells to terminally differentiate, its aberrant activation will inhibit terminal differentiation and could lead to tumor formation. In this scenario, Notch is considered as an oncogene (Fig. 2).35 This is the case in T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (T-ALL), in which the link between activated Notch signaling and cancer first was described. In T-ALL, mutations or constitutive activation of Notch-1, which arise as a result of chromosomal translocation of the C-terminal part of the Notch-1 gene to the T-cell receptor β locus, lead to the expansion of immature T-cells and subsequent development of leukemia.36,37 In tissues, where an active Notch cascade is crucial for proper differentiation, it will function as a tumor suppressor as its inactivation would impede the cell differentiation. This is thought to be the case in mammalian skin where Notch activity has been linked to normal differentiation, and loss of function leads to development of basal-cell-carcinoma-like tumors.38 Furthermore, it is possible that different homologs of the Notch receptor, or its downstream effectors, play diverse roles in the formation of a specific tumor. Fan et al.39 proposed that Notch-1 and Notch-2 mediate opposing effects in the childhood brain tumor medulloblastoma. They showed that while Notch-2 clearly promoted tumorigenesis of medulloblastoma, Notch-1 was inhibitory for tumor growth. This most likely reflects the normal function of the two receptors in the brain, as Notch-2 has been shown to be involved in proliferation of neuronal precursors in the cerebral cortex, whereas Notch-1 has been detected in postmitotic cells.40,41 Thus, it is important to note that the different components of the Notch signaling cascade can play diverse roles in carcinogenesis, possibly reflecting their roles during normal development.

Fig. 2.

Notch as an oncogene or tumor suppressor. It is hypothesized that Notch functions as an oncogene in cells where Notch is activated to maintain an undifferentiated phenotype and has to be down-regulated in order for differentiation to occur. In contrast, in cells where Notch activity is required for differentiation to proceed, it is thought to function as a tumor suppressor as its absence maintains cells in an undifferentiated state.

Notch Signaling in Gliomas

Several studies during recent years have reported dysregulated Notch activity in human brain tumors. However, few studies have investigated the functional relevance in this tumor type. Thus, it is still not clear if, and how, Notch signaling affects glioma tumorigenesis and maintenance. In the following sections, we will summarize our current understanding of Notch signaling in gliomas.

Correlation of Notch Expression and Glioma Grade

Gliomas may arise from tumorigenic events within all steps of maturation from NSC to neurons or glia. Thus, it could be argued that gliomas arising from cells with different maturation grades may display diverse expression profiles of the Notch signaling cascade components, reflecting the cell of origin. It is also possible that these expression profiles could be used to distinguish gliomas of different grades, including primary and secondary GBM. In a study by Somasundaram et al.,42 it was shown that Hash-1 mRNA was elevated in grade II, III, and secondary GBM, whereas its expression was unchanged in primary GBM when compared with normal brain tissue. Furthermore, low-grade astrocytomas and secondary GBM expressed elevated levels of the Notch ligand, Dll-1, which is known to be under the transcriptional control of Hash-1.43 Primary GBM, however, displayed elevated Hes-1 expression indicating activated Notch signaling and offering a possible explanation for the low Hash-1 levels. Thus, it seems as inactive Notch signaling characterizes low-grade astrocytomas and secondary GBM, whereas Notch signaling is activated in primary GBM.

Phillips et al.44 classified tumors into 3 subgroups depending on gene expression, that is, proneural (PN), Prol, and mesenchymal (Mes). The survival within the PN group was markedly longer than that of the Prol and Mes subtypes, and thus, tumor subgroup was shown to have prognostic value independent of histological tumor grade. Nearly all grade III tumors belonged to the PN subgroup which was characterized by expression of neuroblast markers and markers of developing neurons. In line with Somasundaram et al., expression of Dll-1 and Hash-1 was identified in this tumor group, which also contained a subset of grade IV tumors, although the authors did not distinguish between primary and secondary GBM. Furthermore, Dll-3 was identified as a marker for PN tumors, and high Dll-3 levels correlated with a better prognosis in tumors expressing phosphatase and tensin homolog. Dll-3 has been shown to inhibit Notch signaling cell autonomously and promote neurogenesis while inhibiting glial differentiation.45 As such, Dll-3 expression could reflect a more differentiated neuronal phenotype. The correlation between Dll-3 and differentiation is, however, not a consistent finding, as another study showed Dll-3 expression in primary GBM along with a transcript profile indicative of NSC and Mes stem cell-like properties.46

Taken together, these studies imply that Notch signaling plays different roles in the tumorigenesis of low-grade astrocytomas and secondary GBM when compared with primary GBM, possibly indicating that these tumors originate from different precursor cells. As Notch signaling is involved in the differentiation of NSC into astroglia, it could be speculated that Notch would function as a tumor suppressor in low-grade astrocytomas and secondary GBM. However, since Notch signaling is also involved in maintaining an undifferentiated NSC pool and is activated in primary GBM, it is possible that it functions as an oncogene in primary GBM.

Aberrant Expression of Notch-Modulating Components in Human Gliomas

There are several proteins involved in modifying the activity and transcriptional output of Notch signaling. One of these proteins is neuralized (neu), which was originally identified to be involved in neurogenesis in Drosophila. Loss of function mutations in neu leads to extensive production of neurons at the expense of epidermal tissue,47 a phenotype which is similar to that of the Notch mutant. Indeed, neu has been shown to be involved in regulating the Notch signaling cascade as it promotes endocytosis and degradation of Delta.48 The outcome of this is still not clear, but it has been proposed that neu antagonizes the inhibitory effect of Delta on Notch signaling in the same cell, leading to activation of the Notch cascade. One of the genetic features of primary GBM is loss of heterozygosity at chromosome 10q, and consequently, this region has been extensively studied for tumor suppressor genes. By deletion mapping, Nakamura et al. identified a region at 10q25.1 that was frequently lost in grade III astrocytomas and GBM. In this region, they identified a gene with homology to Drosophila neu and which they designated as h-neu. Expression of h-neu was detected in normal brain tissue, whereas it was nearly absent in high-grade astrocytomas and glioma cell lines.49 Thus, h-neu might be a potential tumor suppressor whose inactivation could result in aberrant activation of the Notch signaling cascade thereby promoting development and growth of malignant astrocytomas.

Numb is a membrane-bound protein that is asymmetrically distributed during cell division of NSC and which is implicated in cell fate decisions of neuroepithelial cells. Numb has been shown to promote neuronal differentiation in Drosophila, whereas it has been assigned multiple roles in vertebrate neurogenesis (reviewed by Cayouette and Raff50). Numb has been shown to antagonize Notch signaling, which could explain some of the diverse observations of Numb activation since Notch signaling itself has varied effects on the neuroepithelial cells at different stages of development. Ligand of Numb protein X (LNX) is implicated in degradation of Numb leading to increased Notch signaling.51 Interestingly, LNX transcript has been shown to be down-regulated in human gliomas of various grades when compared with normal brain tissue.52 Furthermore, LNX was shown to interact with Numb indicating that LNX is able to modulate the activity of the Notch signaling cascade. However, the functional relevance of LNX down-regulation in the tumorigenesis of gliomas is still not known.

In conclusion, aberrant expression of proteins involved in modulating the Notch cascade may play important roles in the development of gliomas. If so, this might offer an explanation as to why there are so many inconsistent results regarding expression of the core components of the Notch signaling cascade in this tumor type.

Functional Studies of Notch Signaling in Gliomas

One of the most extensive studies on Notch function in gliomas to date was performed by Purow et al.53 In this study, glioma cell lines were transfected with siRNA against Notch-1, which led to increased cell death, decreased cell proliferation, and a cell cycle block. Morphological changes were also observed as the cells grew extensions reminiscent of neurites, indicating a more differentiated phenotype. This change in morphology, along with up-regulation of the astrocytic marker GFAP, down-regulation of vimentin (an intermediate filament of Mes tissue), as well as decreased cell proliferation upon Notch-1 inhibition, has been corroborated by others.54 After injecting glioma cells expressing siRNA against Notch-1 intracranially into mice, they survived longer than control transfected mice.53 These results suggest that Notch-1 is involved in maintaining glioma cells in an undifferentiated, Prol state, and that its inhibition allows the cells to mature into a less aggressive phenotype. In addition, blocking the Notch-ligand interaction with Fc-conjugated Dll-1, resulted in decreased cell proliferation.53 Blocking either Dll-1 or Jagged-1 expression in glioma cell lines resulted in decreased viability in vitro, although the effect of inhibiting Dll-1 was the most pronounced. This was also observed in vivo where mice injected with siDll-1-transfected cells survived significantly longer than both control mice and mice injected with cells expressing siJagged-1.53 Hence, it is possible that the ligands themselves have transforming potential and thus play a role in gliomagenesis. As Notch-1 expression and activity was more pronounced in grade II and III gliomas than in GBM, whereas the opposite was observed for both Dll-1 and Jagged, it is possible that this pattern of expression is reflective of their roles during normal development (ie, where progenitor cells express either Notch or ligand when differentiating into a glial or neuronal cell fate. As such, GBM tumors would be more like neuronal precursors as judged by their expression of Notch ligands. However, this is in contrast to other studies, as described above, showing that low-grade astrocytomas express the ligands, whereas Notch signaling is activated in primary GBM.42,44 Still, the study by Purow et al.53 clearly shows that glioma cells are sensitive to modulation of the Notch signaling pathway both in vitro and in vivo, a notion that also has been confirmed by others.54–56

Corroborating the importance of Notch signaling in glioma, expression of the Notch target Hey-1 correlates with clinical outcome and survival; patients with Hey-1-negative GBM tumors have a 2-fold longer survival and longer median disease-free survival than patients with Hey-1-positive tumors.57 Furthermore, siRNA against Hey-1 resulted in decreased proliferation of glioma cells with high endogenous expression of Hey-1, whereas low Hey-1-expressing cells remained Prol.57 Interestingly, the two responsive cell lines used in this study are known to originate from GBM, whereas the unresponsive, and low Hey-1-expressing, cell line originates from a grade III astrocytoma. Moreover, Hey-1 correlated with tumor grade as it was more frequently expressed in GBM than in low-grade astrocytomas. It was thus suggested to be an unfavorable prognostic factor in GBM,57 again indicating that Notch signaling plays divergent roles in different types of gliomas.

Expression of the delta-like ligand (DLK, also referred to as pG2 and pref-1) was shown to be increased in gliomas, including a subset of GBM, when compared with normal brain tissue.58 DLK has been suggested to inhibit Notch signaling; however, since DLK lacks the DSL (delta/serrate/LAG-2) region important for ligand interaction with the Notch receptor, its relevance as a Notch ligand has been debated. Nevertheless, Hes-1 mRNA was down-regulated in glioma cells stably transfected with DLK or treated with DLK-conditioned media, indicating an inhibitory effect on Notch signaling.58 Furthermore, DLK-expressing cells grew faster than control cells, and cell cycle analyses showed an increase in cells in the S-phase along with proteins associated with proliferation. In addition, cells expressing DLK formed larger colonies in soft agar and showed increased migratory potential as well as loss of contact inhibition, indicating a more transformed phenotype. As DLK has been suggested to have an oncogenic role in undifferentiated tumors,59 it is possible that DLK may have a role in the progression of GBM.58 In general, inhibition of the Notch signaling cascade does not correlate with increased transformation, as activated Notch is involved in maintaining proliferation of undifferentiated cells. However, considering the role of Notch in terminal glial differentiation, its inhibition would indeed maintain committed glial precursor cells in an undifferentiated Prol state. Once again, this highlights the possibility that expression of Notch pathway components reflect what stage of development the tumors originate from, and also possibly different grades of glioma.

bCSC in Gliomas

Populations of NSC are found in the adult brain and are most abundant in the subventricular zone (SVZ).60 The NSC divide slowly, but give rise to faster dividing progenitor cells, which are committed to a certain lineage and proliferate until terminal differentiation. When grown in serum-free culture conditions in the presence of growth factors, NSC form floating aggregates, called neurospheres, that represent a clonal, single cell-derived cluster of proliferating cells,61,62 and which are used to characterize their self-renewing potential.63 In this Prol undifferentiated form, the cells express the NSC markers nestin and CD133.64,65 By adding serum or withdrawing growth factors, NSC will differentiate into neurons or glia cells, and hence they are multipotent.61

Several groups have reported the existence of neurosphere-forming cells in various grades of gliomas, including GBM.2,3,66–68 Sphere-forming glioma cells are reported to express CD133 and nestin68–70 and have been demonstrated to have multipotent potential, as they differentiate into cells expressing neuronal or glial cell markers upon growth factor depletion.2,3,68,69 In addition to these NSC characteristics, glioma-derived neurospheres or CD133+ cells are tumorigenic and when transplanted into SCID mice; secondary tumors are formed with phenotypic and cytogenetic similarities to the patient tumor from which they were originally derived.2,66–68 On the basis of being self-renewing, multipotent, and tumorigenic, glioma neurosphere-forming cells have been referred to as bCSC. Studies have shown that bCSC could be the cancer cell responsible for brain tumor progression and treatment resistance4,71,72 and may also be involved in tumor angiogenesis by consistently secreting the pro-angiogenic factor vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF).71 Together these findings have led to the theory that initiation of brain tumor growth, cancer progression and propagation, metastasis, treatment resistance, and relapse is governed by a defined cell subpopulation, namely the bCSC.

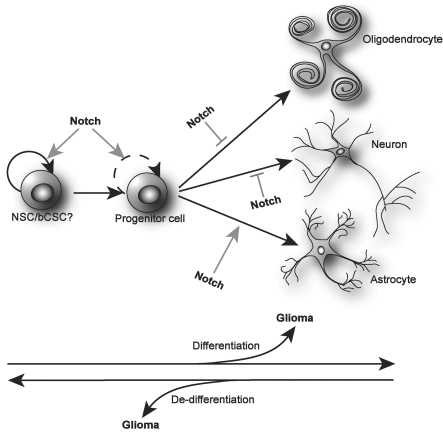

It has not yet been established whether bCSC originate from NSC or from de-differentiation of more mature tumor cells and, as such, are a result of tumor progression (Fig. 3). However, several studies indicate that bCSC originate from NSC.2,3,67,73,74

Fig. 3.

A simplified view of Notch in NSC and development of gliomas. Notch signaling is important for the self-renewal of NSC, and possibly bCSC. From these stem cells, progenitor cells arise that again will form more and more lineage restricted progenitors. In some of these developmental steps, Notch is involved in the self-renewing process of the progenitor cells. Finally, an active Notch cascade is involved in the terminal differentiation of astrocytes and, conversely, inhibits the final maturation of neurons and oligodendrocytes. The cell of origin for gliomas is currently not known. However, it is possible that gliomas might arise from transforming events in every developmental step from the NSC to mature CNS cells. It is also possible that de-differentiation of more mature cells may lead to gliomagenesis. As such the bCSC might be either the initiator of glioma growth or a result of glioma progression.

Notch Signaling in Brain Cancer Stem Cells

Components of the Notch signaling pathway are expressed in neurogenic areas of the adult CNS,75 such as the SVZ, were they maintain a pool of NSC,76 and as mentioned above, are involved in cell fate decisions. Studies have shown that Notch pathway components are expressed, and often found deregulated, in bCSC isolated from GBM and glioma cell lines indicating a role for Notch in bCSC.

In a study by Lee et al., it was shown that GBM cell lines established during NSC culturing conditions more closely shared the pheno- and genotypes of the original GBM tumor, than GBM cell lines established the traditional way in the presence of serum. Furthermore, the established NSC-cultured cell lines clustered together with normal NSC in a global gene expression profile.66 Interestingly, these cell lines expressed high levels of genes involved in CNS function and development, as well as stem cell-associated genes such as Notch-1 and -4 and Dll-1 and -3. On the basis of expression profiling, Gunther et al.70 divided nine cell lines established from GBM under serum-free conditions into two clusters: cluster 1 was classified as having multipotent and sphere-forming potential, CD133 expression, and high invasiveness, whereas cluster 2 had restricted differentiation potential, showed little or no CD133 expression, and was less tumorigenic. The transcripts were grouped according to their association with specific signaling pathways. Two of the transcript groups over-expressed in cluster 1 belonged to the Notch cascade, whereas none of the cluster-2 cell lines showed increased expression of these genes.70 The expression studies outlined above support the idea that Notch signaling plays a role in bCSC characteristics and tumor aggressiveness. This is further supported in a study by Ignatova et al. By culturing cells from glioma grade III–IV tumors under NSC conditions, they found a subset of cultures able to form clonal spheres. In serum-free culture conditions, the sphere cells were negative for Delta expression; however, when the cultures were exposed to serum and allowed to adhere, they gained Delta expression.69 As described above, Delta expression inhibits Notch signaling cell-autonomously and is seen in cells committed to the neuronal lineage where it drives the cell toward terminal neuronal differentiation. As such, it is tempting to speculate that the results of Ignatova et al. indicate that increased differentiation due to inhibited Notch signaling decreases tumorigenicity by reducing the bCSC pool and vice versa.

Few functional Notch studies in bCSC from gliomas have been published. In one study by Zhang et al., it was demonstrated that by stably transfecting a cell line with exogenous ICN they obtained a cell line, which grew significantly faster and had significantly higher colony- and sphere-forming abilities than the parental and control cell lines. The presence of bCSC was confirmed as the spheres tested positive for nestin and could differentiate into the three neural lineages, further indicating that active Notch signaling has a role in tumorigenicity and bCSC self-renewal.56 However, the most compelling evidence for Notch signaling in bCSC comes from a study in embryonal brain tumor medulloblastoma cells. When investigating medulloblastoma cell lines, Fan et al. found that the activity of the Notch signaling cascade was elevated in the CD133+ cell fraction. Inhibiting Notch-2 signaling resulted in diminished proliferation, increased neuronal differentiation, a reduced CD133+ cell fraction in vitro, and decreased tumorigenicity in vivo. In contrast, by activating Notch-2 signaling, they found that the CD133+ cell fraction was expanded. Similar results were obtained when characterizing the bCSC by their nestin expression in which an increase in apoptotic events upon Notch blockade was evident.77

Taken together, these data indicate strongly that bCSC may by the cell responsible for tumor formation and treatment failure. It is known that Notch signaling is important in maintaining normal NSC, and components of the Notch cascade have been found to be expressed aberrantly in bCSC and are indicated to support bCSC characteristics.

Notch and Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor Cross-Talk in Gliomas

Primary GBM is characterized by frequent over-expression and dysregulated activity of the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) as a result of amplification and/or mutation.78,79 EGFR signaling is involved in regulating cellular processes, such as proliferation, migration, and survival. Two of the signaling pathways downstream of EGFR are the RAS/MEK/ERK and PI3-K/AKT pathways. Several lines of evidence indicate that the Notch pathway is intimately coupled to signaling through EGFR, or downstream targets, in both normal development and in the onset and maintenance of cancer.80–83 In addition, the cross-talk between the Notch pathway and EGFR signaling has been revealed in tumor angiogenesis.84

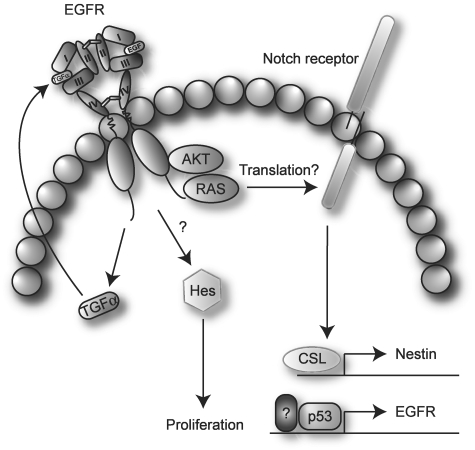

In the brain, EGFR is expressed in neurogenic regions such as the SVZ,85 and the Notch pathway has been implicated in regulating survival and proliferation of NSC through signaling pathways downstream of EGFR.86 Based on the established Notch/EGFR interplay in several other tumor types,80–83 the high frequency of dysregulated EGFR activity in GBM, and the importance of Notch signaling in neurogenesis, it may be assumed that these pathways interact also in glioma (Fig. 4). Indeed, RAS-transformed human astrocytes have been shown to express more Notch-1 than their untransformed counterparts and are also more sensitive toward γ-secretase inhibition and siRNA against Notch-1.54 Furthermore, inhibition of Notch signaling in these cells led to changes in cellular morphology and marker expression, indicative of glial differentiation, and a less aggressive phenotype. As it was possible to inhibit the growth of RAS-transformed astrocytes by blocking Notch activity, it was speculated that Notch played a role in the transformation process. However, introduction of ICN in immortalized astrocytes did not lead to transformation on its own, and over-expression of constitutively activated Notch in RAS-transformed astrocytes did not enhance tumorigenesis.54 These results are somewhat in contrast to a study by Shih et al.,87 who observed that expression of ICN together with K-RAS in glial progenitors induced periventricular lesions in the SVZ. These lesions showed an active proliferation and were positive for nestin expression. It was suggested that Notch is able to cooperate with K-RAS to produce lesions that are stem cell-like as judged from their location in the SVZ, their proliferation, and stem cell marker expression. Since neither ICN nor K-RAS alone were able to induce these lesions, the results indicate a synergistic effect on transformation. Furthermore, Notch-1 expression was induced by RAS and AKT in a mouse glioma model, possibly by increased translation, and even more intriguing, nestin was shown to be a direct transcriptional target of Notch.87,88 Thus, dysregulated RAS activation may induce Notch-1 which then drives the expression of nestin, maintaining progenitor characteristics, and ultimately induces oncogenic lesions in concert with RAS. When considering a stem cell origin for gliomas, these results are highly relevant as nestin positive progenitor cells in the SVZ might be blocked from terminal differentiation by the combined activation of Notch and RAS.

Fig. 4.

Schematic illustration of Notch and EGFR cross-talk in glioma. Activation of AKT and/or RAS induces expression of Notch, possibly by recruiting existing Notch mRNAs to polysomes and increasing translation. Notch drives the expression of Nestin and EGFR, in part through activation of p53. Signaling through EGFR up-regulates TGFα, which induces expression of Hes and leads to proliferation. The mechanism behind up-regulation of Hes by TGFα is currently not elucidated but has been suggested to occur without Notch activation. See text for further details.

It is important to emphasize that high RAS activity is not necessarily a consequence of deregulated EGFR, as several other growth factor receptors also signal through RAS and thus could interact with the Notch pathway. A direct link between Notch and EGFR in gliomas was, however, provided by Purow et al.89 who showed that EGFR is under the transcriptional control of Notch signaling. They further showed that EGFR and Notch-1 mRNA correlated significantly in high-grade astrocytomas not amplified for the EGFR gene. However, these results did not include the activation status of the Notch signaling pathway, and further studies are needed to investigate the relationship between the Notch and EGFR signaling pathways in vivo. Still, the observation that Notch is able to drive the expression of EGFR is intriguing.

EGFR itself has been suggested to induce TGF-α expression, thus providing an autocrine loop for EGFR activity (reviewed by Tang et al.90). Furthermore, TGF-α expression correlates with tumor grade, with the highest expression observed in high-grade gliomas.91 In a recent study, evidence was provided for TGF-α regulating the signaling output of the Notch cascade in glioma92 as has been shown earlier in neuroblastoma.81 TGF-α treatment of glioma cells resulted in increased proliferation and up-regulation of Hes-1 at both the transcriptional and translational level, as well as Hes-1 nuclear translocation. Hes-1 up-regulation was suggested to be independent of Notch-1, as both mRNA and protein expression of Notch-1 and RBP-Jκ were unaffected by TGF-α stimulation. However, as the activation of Notch-1 occurs post-transcriptionally, without affecting the level of either Notch-1 or RBP-Jκ mRNA, this conclusion has to be verified by other experiments. Furthermore, up-regulation of Hes-1 was independent of ERK1/2 activity, which is in contrast to what has been shown in other studies.81 However, the nuclear translocation of Hes-1 that was observed upon TGF-α stimulation was blocked by MEK1/2 inhibition, indicating that ERK1/2 activity is crucial for this process. As TGF-α enhances glioma proliferation and causes up-regulation and nuclear translocation of Hes-1, and since inhibition of γ-secretase down-regulates Hes-1 expression along with decreased glioma cell growth (which can be rescued by TGF-α in part), it is most likely that Hes-1 induced by TGF-α is crucial for glioma growth. However, the exact mechanism behind TGF-α-induced Hes-1 up-regulation needs further clarification.

Complicating the Glioma Picture: Notch Signaling in Hypoxia and Angiogenesis

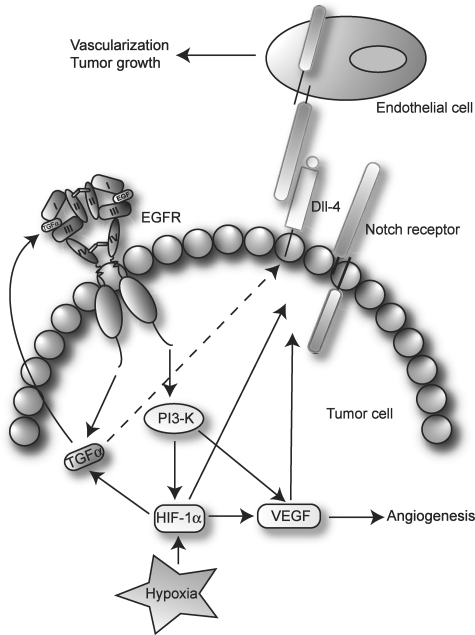

Solid tumors are unable to grow beyond a couple of millimeters without neo-vascularization providing oxygen and nutrients to the tumor cells. Extensive angiogenesis is a hallmark of GBM, and tumor vascularity is significantly correlated with poor survival.93 Furthermore, widespread areas of necrosis, as a result of hypoxia, are present. In response to hypoxia, the hypoxia inducible factors (HIF)-1α and -2α are stabilized and, as a consequence, pro-angiogenic factors (eg, VEGF) involved in the formation of new blood vessels, and growth factors such as TGF-α are up-regulated. Even if hypoxia elicits an angiogenic response in tumors such as GBM, tumor vessels are often malformed and occlusions are frequent, and as such intratumoral hypoxic areas will remain. There is growing evidence that the cellular response to hypoxia and the Notch signaling pathway are intimately connected both in normal cells and in cancer (for review see Poellinger and Lendahl9). For example, hypoxia has been shown to induce the expression of several components of the Notch signaling cascade, such as Notch-1, Hes-1, Hey-1, Dll-1, and Dll-4 (Fig. 5).9 It is well known that hypoxia promotes NSC self-renewal (for review see Zhu et al.94), and from a glioma perspective, the finding that Notch was required to maintain an undifferentiated state of NSC in the presence of hypoxia is intriguing.95 However, there are thus far no studies that highlight the interplay between Notch and hypoxia in glioma tumorigenicity.

Fig. 5.

Potential Notch and EGFR interaction in glioma angiogenesis. Hypoxia and EGFR both induce expression of TGFα, creating an autocrine loop for EGFR activation. Upon EGFR signaling and in response to hypoxia, HIF-1α and VEGF that are involved in angiogenesis are up-regulated. Furthermore, Notch receptors and ligands are induced by HIF-1α and VEGF. Dll-4 expression in glioma tumor cells activates Notch signaling in nearby endothelial cells leading to vascularization and tumor growth. See text for further details.

Accumulating data indicate that Notch signaling plays a significant role in tumor angiogenesis. Various genetic studies have highlighted the importance of Notch signaling for proper vascular formation during normal development (for review see Rehman and Wang8). For example, haplo-insufficiency of Dll-4 in mice results in embryonic lethality due to defective vascular development.96 Interestingly, Dll4 and VEGF are the only genes that are known to cause embryonic lethality due to malfunctional blood vessels in response to loss of a single allele. Expression of Dll-4 has been shown to be up-regulated in tumor vessels of several human tumors97 and its expression correlates with VEGF levels in clear cell-renal carcinoma.98 Furthermore, and as mentioned above, Dll-4 has been shown to be induced by hypoxia, and more specifically, by HIF-1α, VEGF, and bFGF.97–99 In addition, VEGF has been shown to induce expression of Notch-1 in arterial endothelial cells,99 indicating that pro-angiogenic factors activate Notch signaling, which in turn can promote angiogenesis (Fig. 5). Several studies have shown that blocking of Dll-4 in vivo leads to increased vessel density; however, the vessels are poorly functional with decreased perfusion, and as a result tumor growth is inhibited.100,101 In line with this, Dll-4 expression in a glioma xenograft model significantly enhanced tumor growth along with up-regulation of Dll-4 and Hes-1 mRNA in host endothelial cells.102 The tumors displayed decreased vessel density and number, although the vessels were larger and the tumors were better perfused than in control-transfected tumors, resulting in decreased intratumoral hypoxia and necrotic areas. These observations indicate that there is a role for Dll-4 in tumor vascularization. Dll-4 mRNA was shown to be present in tumor endothelial cells in 15 out of 20 human GBM examined, whereas expression was totally absent in control samples. Furthermore, Dll-4 was also detected in tumor cells in 4 of 20 cases. It is thus possible that tumor Dll-4 expression is able to activate Notch signaling in host endothelial cells as has been shown previously for other Notch ligands in head and neck squamous carcinoma cells.84 In this study, Jagged-1 expression in tumor cells activated Notch signaling in nearby endothelial cells, triggering capillary sprout formation and neo-vascularization.84 As Dll-4 is a HIF-1α and VEGF target, which are expressed in response to hypoxia and also in response to TGFα/EGFR signaling,103,104 it is likely that Dll-4 is a central player in glioma, possibly by activating Notch signaling and stimulating angiogenesis (Fig. 5). However, further research has to be performed to elucidate the function of Dll-4 in glioma malignancy. Nevertheless, Notch signaling does play a role in glioma angiogenesis, which has been further corroborated by Paris et al.105 who used various γ-secretase inhibitors in a glioma xenograft model. Here, they showed that γ-secretase inhibition reduced tumor volume with a concomitant decrease in vascularization. However, these effects cannot exclusively be attributed to reduced Notch activity as γ-secretase inhibitors also are involved in the processing of other proteins associated with the angiogenic response. Still, since Notch signaling plays such a fundamental role in normal angiogenesis and in the response to hypoxia, it is feasible that it is also involved in glioma pathogenesis, and especially GBM, since hypoxia and angiogenesis are so prominent in this tumor type.

Notch as a Therapeutic Target in Gliomas

On the basis of the observations regarding Notch in gliomas, its role in NSC/bCSC, hypoxia and angiogenesis, and its interplay with EGFR, the Notch signaling pathway may be a potential target for glioma therapy. Inhibition of Notch activation with γ-secretase inhibitors has been the most extensively used approach to target Notch and is also the most likely strategy for cancer therapy in the near future. Indeed, the γ-secretase inhibitor MK0752 (Merck) has recently been used in a phase I clinical trial for relapsed or refractory T-ALL, and another phase I study is currently recruiting patients with advanced breast cancer or other solid tumors that have failed at least one prior treatment regimen (http://www.clinicaltrials.gov). However, as γ-secretase inhibition affects all Notch receptors, it is difficult to anticipate the specific outcome on a particular cell type. As such, unwanted side effects using γ-secretase inhibitors have been observed. One of the most common side effects is metaplasia of goblet cells in the small intestine,106 which is alleviated by intermittent rather than continuous administration of the γ-secretase inhibitor, presumably by allowing proper differentiation of intestinal stem cells. Furthermore, γ-secretase inhibitors are not specific for Notch receptors and effects on other targets are to be expected. As reviewed above, several studies have investigated the effect of γ-secretase inhibition on glioma cells in vitro and in vivo, most of which showed an inhibitory effect on cell/tumor growth. γ-Secretase inhibitors may therefore be effective also when treating glioma patients. When considering the cross-talk between Notch signaling and the RAS/MEK/ERK and PI3-K/AKT pathways downstream of EGFR and their roles in experimental gliomas, it is tempting to speculate that simultaneous inhibition of several of these pathways could lead to improved treatment of glioma patients.

Recently, anti-angiogenic therapies targeting factors, such as VEGF, have received much attention in cancer treatment. The humanized monoclonal anti-VEGF antibody bevacizumab (Avastin®) has been used in clinical trials at various institutions for the treatment of recurrent high-grade gliomas.107,108 Results show improved treatment outcomes, with more complete responses and partial responses than obtained with other second-line treatments. However, even though treatment was initially effective, drug resistance and re-growth of tumors have been observed.109 This is most likely due to activation of pro-angiogenic pathways other than VEGF. As Notch signaling, and especially Dll-4, is involved in tumor angiogenesis, it is likely that this pathway is involved in anti-VEGF resistance. Indeed, although initially responsive to bevacizumab, Dll-4-expressing U87MG glioma cells continued to grow at the same rate as control-treated tumors after terminating treatment.102 Blocking Notch signaling by using a soluble form of Dll-4 reduced tumor burden and prolonged survival of the Dll-4 expressing tumors. Most importantly, soluble Dll-4 inhibited growth of both bevacizumab-sensitive and -insensitive tumors indicating that targeting Notch in addition to VEGF would result in improved treatment outcome.

In conclusion, the Notch signaling pathway is involved in a plethora of cell fate decisions and cellular processes that are implicated in the tumorigenesis of gliomas. By targeting the Notch pathway, it may be possible to interfere with these processes leading to a better treatment outcome for patients, especially those with high-grade astrocytic gliomas. In addition, if Notch signaling plays a role in bCSC, and if these cells are crucial for glioma maintenance, it may be possible to target these tumor-initiating cells by inhibiting the Notch pathway.

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

Funding

This study was supported by Copenhagen University Hospital, the Danish National Board of Health (journal number: 2006-12103-254) and the Danish Cancer Society (journal number: DS08030).

References

- 1.Stupp R, Mason WP, van den Bent MJ, et al. Radiotherapy plus concomitant and adjuvant temozolomide for glioblastoma. N Engl J Med. 2005;10:987–996. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Galli R, Binda E, Orfanelli U, et al. Isolation and characterization of tumorigenic, stem-like neural precursors from human glioblastoma. Cancer Res. 2004;19:7011–7021. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-1364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Singh SK, Clarke ID, Terasaki M, et al. Identification of a cancer stem cell in human brain tumors. Cancer Res. 2003;18:5821–5828. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bao S, Wu Q, McLendon RE, et al. Glioma stem cells promote radioresistance by preferential activation of the DNA damage response. Nature. 2006;444:756–760. doi: 10.1038/nature05236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Artavanis-Tsakonas S, Rand MD, Lake RJ. Notch signaling: cell fate control and signal integration in development. Science. 1999;5415:770–776. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5415.770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Koch U, Radtke F. Notch and cancer: a double-edged sword. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2007;21:2746–2762. doi: 10.1007/s00018-007-7164-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gaiano N, Fishell G. The role of notch in promoting glial and neural stem cell fates. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2002;25:471–490. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.25.030702.130823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rehman AO, Wang CY. Notch signaling in the regulation of tumor angiogenesis. Trends Cell Biol. 2006;6:293–300. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2006.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Poellinger L, Lendahl U. Modulating Notch signaling by pathway-intrinsic and pathway-extrinsic mechanisms. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2008;18:449–454. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2008.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fischer I, Gagner JP, Law M, Newcomb EW, Zagzag D. Angiogenesis in gliomas: biology and molecular pathophysiology. Brain Pathol. 2005;4:297–310. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.2005.tb00115.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Logeat F, Bessia C, Brou C, et al. The Notch1 receptor is cleaved constitutively by a furin-like convertase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;14:8108–8112. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.14.8108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Blaumueller CM, Qi H, Zagouras P, Rtavanis-Tsakonas S. Intracellular cleavage of Notch leads to a heterodimeric receptor on the plasma membrane. Cell. 1997;2:281–291. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80336-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lindsell CE, Shawber CJ, Boulter J, Weinmaster G. Jagged: a mammalian ligand that activates Notch1. Cell. 1995;6:909–917. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90294-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Luo B, Aster JC, Hasserjian RP, Kuo F, Sklar J. Isolation and functional analysis of a cDNA for human Jagged2, a gene encoding a ligand for the Notch1 receptor. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;10:6057–6067. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.10.6057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gray GE, Mann RS, Mitsiadis E, et al. Human ligands of the Notch receptor. Am J Pathol. 1999;3:785–794. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)65325-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dunwoodie SL, Henrique D, Harrison SM, Beddington RS. Mouse Dll3: a novel divergent Delta gene which may complement the function of other Delta homologues during early pattern formation in the mouse embryo. Development. 1997;16:3065–3076. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.16.3065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shutter JR, Scully S, Fan W, et al. Dll4, a novel Notch ligand expressed in arterial endothelium. Genes Dev. 2000;11:1313–1318. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mumm JS, Schroeter EH, Saxena MT, et al. A ligand-induced extracellular cleavage regulates gamma-secretase-like proteolytic activation of Notch1. Mol Cell. 2000;2:197–206. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80416-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brou C, Logeat F, Gupta N, et al. A novel proteolytic cleavage involved in Notch signaling: the role of the disintegrin-metalloprotease TACE. Mol Cell. 2000;2:207–216. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80417-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.De SB, Annaert W, Cupers P, et al. A presenilin-1-dependent gamma-secretase-like protease mediates release of Notch intracellular domain. Nature. 1999;6727:518–522. doi: 10.1038/19083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jarriault S, Brou C, Logeat F, Schroeter EH, Kopan R, Israel A. Signalling downstream of activated mammalian Notch. Nature. 1995;6547:355–358. doi: 10.1038/377355a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kao HY, Ordentlich P, Koyano-Nakagawa N, et al. A histone deacetylase corepressor complex regulates the Notch signal transduction pathway. Genes Dev. 1998;15:2269–2277. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.15.2269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kurooka H, Honjo T. Functional interaction between the mouse notch1 intracellular region and histone acetyltransferases PCAF and GCN5. J Biol Chem. 2000;22:17211–17220. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M000909200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Iso T, Kedes L, Hamamori Y. HES and HERP families: multiple effectors of the Notch signaling pathway. J Cell Physiol. 2003;3:237–255. doi: 10.1002/jcp.10208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kageyama R, Ohtsuka T, Hatakeyama J, Ohsawa R. Roles of bHLH genes in neural stem cell differentiation. Exp Cell Res. 2005;2:343–348. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2005.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ronchini C, Capobianco AJ. Induction of cyclin D1 transcription and CDK2 activity by Notch(ic): implication for cell cycle disruption in transformation by Notch(ic) Mol Cell Biol. 2001;17:5925–5934. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.17.5925-5934.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rangarajan A, Talora C, Okuyama R, et al. Notch signaling is a direct determinant of keratinocyte growth arrest and entry into differentiation. EMBO J. 2001;13:3427–3436. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.13.3427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ge W, Martinowich K, Wu X, et al. Notch signaling promotes astrogliogenesis via direct CSL-mediated glial gene activation. J Neurosci Res. 2002;6:848–860. doi: 10.1002/jnr.10364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Martinez AA, Zecchini V, Brennan K. CSL-independent Notch signalling: a checkpoint in cell fate decisions during development? Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2002;5:524–533. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(02)00336-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Beatus P, Lendahl U. Notch and neurogenesis. J Neurosci Res. 1998;2:125–136. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4547(19981015)54:2<125::AID-JNR1>3.0.CO;2-G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lasky JL, Wu H. Notch signaling, brain development, and human disease. Pediatr Res. 2005 doi: 10.1203/01.PDR.0000159632.70510.3D. 5(pt 2) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nye JS, Kopan R, Axel R. An activated Notch suppresses neurogenesis and myogenesis but not gliogenesis in mammalian cells. Development. 1994;9:2421–2430. doi: 10.1242/dev.120.9.2421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Morrison SJ, Perez SE, Qiao Z, et al. Transient Notch activation initiates an irreversible switch from neurogenesis to gliogenesis by neural crest stem cells. Cell. 2000;5:499–510. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80860-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang S, Sdrulla AD, diSibio G, et al. Notch receptor activation inhibits oligodendrocyte differentiation. Neuron. 1998;1:63–75. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80515-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Maillard I, Pear WS. Notch and cancer: best to avoid the ups and downs. Cancer Cell. 2003;3:203–205. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(03)00052-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ellisen LW, Bird J, West DC, et al. TAN-1, the human homolog of the Drosophila notch gene, is broken by chromosomal translocations in T lymphoblastic neoplasms. Cell. 1991;4:649–661. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90111-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Weng AP, Ferrando AA, Lee W, et al. Activating mutations of NOTCH1 in human T cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Science. 2004;5694:269–271. doi: 10.1126/science.1102160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nicolas M, Wolfer A, Raj K, et al. Notch1 functions as a tumor suppressor in mouse skin. Nat Genet. 2003;3:416–421. doi: 10.1038/ng1099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fan X, Mikolaenko I, Elhassan I, et al. Notch1 and notch2 have opposite effects on embryonal brain tumor growth. Cancer Res. 2004;21:7787–7793. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-1446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Solecki DJ, Liu XL, Tomoda T, Fang Y, Hatten ME. Activated Notch2 signaling inhibits differentiation of cerebellar granule neuron precursors by maintaining proliferation. Neuron. 2001;4:557–568. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00395-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Irvin DK, Zurcher SD, Nguyen T, Weinmaster G, Kornblum HI. Expression patterns of Notch1, Notch2, and Notch3 suggest multiple functional roles for the Notch-DSL signaling system during brain development. J Comp Neurol. 2001;2:167–181. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Somasundaram K, Reddy SP, Vinnakota K, et al. Upregulation of ASCL1 and inhibition of Notch signaling pathway characterize progressive astrocytoma. Oncogene. 2005;47:7073–7083. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Castro DS, Skowronska-Krawczyk D, Armant O, et al. Proneural bHLH and Brn proteins coregulate a neurogenic program through cooperative binding to a conserved DNA motif. Dev Cell. 2006;6:831–844. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2006.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Phillips HS, Kharbanda S, Chen R, et al. Molecular subclasses of high-grade glioma predict prognosis, delineate a pattern of disease progression, and resemble stages in neurogenesis. Cancer Cell. 2006;3:157–173. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ladi E, Nichols JT, Ge W, et al. The divergent DSL ligand Dll3 does not activate Notch signaling but cell autonomously attenuates signaling induced by other DSL ligands. J Cell Biol. 2005;6:983–992. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200503113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tso CL, Shintaku P, Chen J, et al. Primary glioblastomas express mesenchymal stem-like properties. Mol Cancer Res. 2006;9:607–619. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-06-0005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Boulianne GL, de la CA, Campos-Ortega JA, Jan LY, Jan YN. The Drosophila neurogenic gene neuralized encodes a novel protein and is expressed in precursors of larval and adult neurons. EMBO J. 1991;10:2975–2983. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1991.tb07848.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lai EC. Protein degradation: four E3s for the notch pathway. Curr Biol. 2002;2:R74–R78. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(01)00679-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nakamura H, Yoshida M, Tsuiki H, et al. Identification of a human homolog of the Drosophila neuralized gene within the 10q25.1 malignant astrocytoma deletion region. Oncogene. 1998;8:1009–1019. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1201618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cayouette M, Raff M. Asymmetric segregation of Numb: a mechanism for neural specification from Drosophila to mammals. Nat Neurosci. 2002;12:1265–1269. doi: 10.1038/nn1202-1265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nie J, McGill MA, Dermer M, Dho SE, Wolting CD, McGlade CJ. LNX functions as a RING type E3 ubiquitin ligase that targets the cell fate determinant Numb for ubiquitin-dependent degradation. EMBO J. 2002;1–2:93–102. doi: 10.1093/emboj/21.1.93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chen J, Xu J, Zhao W, et al. Characterization of human LNX, a novel ligand of Numb protein X that is downregulated in human gliomas. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2005;11:2273–2283. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2005.02.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Purow BW, Haque RM, Noel MW, et al. Expression of Notch-1 and its ligands, Delta-like-1 and Jagged-1, is critical for glioma cell survival and proliferation. Cancer Res. 2005;6:2353–2363. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-1890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kanamori M, Kawaguchi T, Nigro JM, et al. Contribution of Notch signaling activation to human glioblastoma multiforme. J Neurosurg. 2007;3:417–427. doi: 10.3171/jns.2007.106.3.417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gao X, Deeb D, Jiang H, Liu Y, Dulchavsky SA, Gautam SC. Synthetic triterpenoids inhibit growth and induce apoptosis in human glioblastoma and neuroblastoma cells through inhibition of prosurvival Akt, NF-kappaB and Notch1 signaling. J Neurooncol. 2007;2:147–157. doi: 10.1007/s11060-007-9364-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zhang XP, Zheng G, Zou L, et al. Notch activation promotes cell proliferation and the formation of neural stem cell-like colonies in human glioma cells. Mol Cell Biochem. 2008;1–2:101–108. doi: 10.1007/s11010-007-9589-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hulleman E, Quarto M, Vernell R, et al. A role for the transcription factor HEY1 in glioblastoma. J Cell Mol Med. 2009;13:136–146. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2008.00307.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yin D, Xie D, Sakajiri S, et al. DLK1: increased expression in gliomas and associated with oncogenic activities. Oncogene. 2006;13:1852–1861. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Laborda J, Sausville EA, Hoffman T, Notario V. dlk, a putative mammalian homeotic gene differentially expressed in small cell lung carcinoma and neuroendocrine tumor cell line. J Biol Chem. 1993;6:3817–3820. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lee A, Kessler JD, Read TA, et al. Isolation of neural stem cells from the postnatal cerebellum. Nat Neurosci. 2005;6:723–729. doi: 10.1038/nn1473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Reynolds BA, Weiss S. Clonal and population analyses demonstrate that an EGF-responsive mammalian embryonic CNS precursor is a stem cell. Dev Biol. 1996;1:1–13. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1996.0090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Svendsen CN, ter Borg MG, Armstrong RJ, et al. A new method for the rapid and long term growth of human neural precursor cells. J Neurosci Methods. 1998;2:141–152. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0270(98)00126-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Engstrom CM, Demers D, Dooner M, et al. A method for clonal analysis of epidermal growth factor-responsive neural progenitors. J Neurosci Methods. 2002;2:111–121. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0270(02)00074-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kukekov VG, Laywell ED, Suslov O, et al. Multipotent stem/progenitor cells with similar properties arise from two neurogenic regions of adult human brain. Exp Neurol. 1999;2:333–344. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1999.7028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Uchida N, Buck DW, He D, et al. Direct isolation of human central nervous system stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;26:14720–14725. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.26.14720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lee J, Kotliarova S, Kotliarov Y, et al. Tumor stem cells derived from glioblastomas cultured in bFGF and EGF more closely mirror the phenotype and genotype of primary tumors than do serum-cultured cell lines. Cancer Cell. 2006;5:391–403. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.03.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Singh SK, Hawkins C, Clarke ID, et al. Identification of human brain tumour initiating cells. Nature. 2004;7015:396–401. doi: 10.1038/nature03128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Yuan X, Curtin J, Xiong Y, et al. Isolation of cancer stem cells from adult glioblastoma multiforme. Oncogene. 2004;58:9392–9400. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ignatova TN, Kukekov VG, Laywell ED, Suslov ON, Vrionis FD, Steindler DA. Human cortical glial tumors contain neural stem-like cells expressing astroglial and neuronal markers in vitro. Glia. 2002;3:193–206. doi: 10.1002/glia.10094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Gunther HS, Schmidt NO, Phillips HS, et al. Glioblastoma-derived stem cell-enriched cultures form distinct subgroups according to molecular and phenotypic criteria. Oncogene. 2008;20:2897–2909. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Bao S, Wu Q, Sathornsumetee S, et al. Stem cell-like glioma cells promote tumor angiogenesis through vascular endothelial growth factor. Cancer Res. 2006;16:7843–7848. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-1010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Liu G, Yuan X, Zeng Z, et al. Analysis of gene expression and chemoresistance of CD133+ cancer stem cells in glioblastoma. Mol Cancer. 2006;5:67. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-5-67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Globus JH, Kuhlenbeck H. The subependymal cell plate (matrix) and its relationship to brain tumors of the ependymal type. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 1944;1:1–35. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Shiras A, Chettiar ST, Shepal V, Rajendran G, Prasad GR, Shastry P. Spontaneous transformation of human adult nontumorigenic stem cells to cancer stem cells is driven by genomic instability in a human model of glioblastoma. Stem Cells. 2007;6:1478–1489. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2006-0585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Stump G, Durrer A, Klein AL, Lutolf S, Suter U, Taylor V. Notch1 and its ligands Delta-like and Jagged are expressed and active in distinct cell populations in the postnatal mouse brain. Mech Dev. 2002;1–2:153–159. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(02)00043-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Yoon K, Gaiano N. Notch signaling in the mammalian central nervous system: insights from mouse mutants. Nat Neurosci. 2005;6:709–715. doi: 10.1038/nn1475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Fan X, Matsui W, Khaki L, et al. Notch pathway inhibition depletes stem-like cells and blocks engraftment in embryonal brain tumors. Cancer Res. 2006;15:7445–7452. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-0858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Tohma Y, Gratas C, Biernat W, et al. PTEN (MMAC1) mutations are frequent in primary glioblastomas (de novo) but not in secondary glioblastomas. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 1998;7:684–689. doi: 10.1097/00005072-199807000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Wong AJ, Bigner SH, Bigner DD, Kinzler KW, Hamilton SR, Vogelstein B. Increased expression of the epidermal growth factor receptor gene in malignant gliomas is invariably associated with gene amplification. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1987;19:6899–6903. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.19.6899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Fitzgerald K, Harrington A, Leder P. Ras pathway signals are required for notch-mediated oncogenesis. Oncogene. 2000;37:4191–4198. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Stockhausen MT, Sjolund J, Axelson H. Regulation of the Notch target gene Hes-1 by TGFalpha induced Ras/MAPK signaling in human neuroblastoma cells. Exp Cell Res. 2005;1:218–228. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2005.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Weijzen S, Rizzo P, Braid M, et al. Activation of Notch-1 signaling maintains the neoplastic phenotype in human Ras-transformed cells. Nat Med. 2002;9:979–986. doi: 10.1038/nm754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Miyamoto Y, Maitra A, Ghosh B, et al. Notch mediates TGF alpha-induced changes in epithelial differentiation during pancreatic tumorigenesis. Cancer Cell. 2003;6:565–576. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(03)00140-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Zeng Q, Li S, Chepeha DB, et al. Crosstalk between tumor and endothelial cells promotes tumor angiogenesis by MAPK activation of Notch signaling. Cancer Cell. 2005;1:13–23. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Weickert CS, Webster MJ, Colvin SM, et al. Localization of epidermal growth factor receptors and putative neuroblasts in human subependymal zone. J Comp Neurol. 2000;3:359–372. doi: 10.1002/1096-9861(20000731)423:3<359::aid-cne1>3.0.co;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Androutsellis-Theotokis A, Leker RR, Soldner F, et al. Notch signalling regulates stem cell numbers in vitro and in vivo. Nature. 2006;7104:823–826. doi: 10.1038/nature04940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Shih AH, Holland EC. Notch signaling enhances nestin expression in gliomas. Neoplasia. 2006;12:1072–1082. doi: 10.1593/neo.06526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Rajasekhar VK, Viale A, Socci ND, Wiedmann M, Hu X, Holland EC. Oncogenic Ras and Akt signaling contribute to glioblastoma formation by differential recruitment of existing mRNAs to polysomes. Mol Cell. 2003;4:889–901. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00395-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Purow BW, Sundaresan TK, Burdick MJ, et al. Notch-1 regulates transcription of the epidermal growth factor receptor through. Carcinogenesis. 2008;5:53–925. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgn079. 918 pp. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Tang P, Steck PA, Yung WK. The autocrine loop of TGF-alpha/EGFR and brain tumors. J Neurooncol. 1997;3:303–314. doi: 10.1023/a:1005824802617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Schlegel U, Moots PL, Rosenblum MK, Thaler HT, Furneaux HM. Expression of transforming growth factor alpha in human gliomas. Oncogene. 1990;12:1839–1842. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Zheng Y, Lin L, Zheng Z. TGF-alpha induces upregulation and nuclear translocation of Hes1 in glioma cell. Cell Biochem Funct. 2008;6:692–700. doi: 10.1002/cbf.1494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Birlik B, Canda S, Ozer E. Tumour vascularity is of prognostic significance in adult, but not paediatric astrocytomas. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 2006;5:532–538. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2990.2006.00763.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Zhu LL, Wu LY, Yew DT, Fan M. Effects of hypoxia on the proliferation and differentiation of NSCs. Mol Neurobiol. 2005;1–3:231–242. doi: 10.1385/MN:31:1-3:231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Gustafsson MV, Zheng X, Pereira T, et al. Hypoxia requires notch signaling to maintain the undifferentiated cell state. Dev Cell. 2005;5:617–628. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2005.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Gale NW, Dominguez MG, Noguera I, et al. Haploinsufficiency of delta-like 4 ligand results in embryonic lethality due to major defects in arterial and vascular development. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;45:15949–15954. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0407290101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Mailhos C, Modlich U, Lewis J, Harris A, Bicknell R, Ish-Horowicz D. Delta4, an endothelial specific notch ligand expressed at sites of physiological and tumor angiogenesis. Differentiation. 2001;2–3:135–144. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-0436.2001.690207.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Patel NS, Li JL, Generali D, Poulsom R, Cranston DW, Harris AL. Up-regulation of delta-like 4 ligand in human tumor vasculature and the role of basal expression in endothelial cell function. Cancer Res. 2005;19:8690–8697. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Liu ZJ, Shirakawa T, Li Y, et al. Regulation of Notch1 and Dll4 by vascular endothelial growth factor in arterial endothelial cells: implications for modulating arteriogenesis and angiogenesis. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;1:14–25. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.1.14-25.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Noguera-Troise I, Daly C, Papadopoulos NJ, et al. Blockade of Dll4 inhibits tumour growth by promoting non-productive angiogenesis. Nature. 2006;7122:1032–1037. doi: 10.1038/nature05355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Ridgway J, Zhang G, Wu Y, et al. Inhibition of Dll4 signalling inhibits tumour growth by deregulating angiogenesis. Nature. 2006;7122:1083–1087. doi: 10.1038/nature05313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Li JL, Sainson RC, Shi W, et al. Delta-like 4 Notch ligand regulates tumor angiogenesis, improves tumor vascular function, and promotes tumor growth in vivo. Cancer Res. 2007;23:11244–11253. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-0969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Semenza GL. Targeting HIF-1 for cancer therapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2003;10:721–732. doi: 10.1038/nrc1187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Maity A, Pore N, Lee J, Solomon D, O'Rourke DM. Epidermal growth factor receptor transcriptionally up-regulates vascular endothelial growth factor expression in human glioblastoma cells via a pathway involving phosphatidylinositol 3'-kinase and distinct from that induced by hypoxia. Cancer Res. 2000;20:5879–5886. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Paris D, Quadros A, Patel N, DelleDonne A, Humphrey J, Mullan M. Inhibition of angiogenesis and tumor growth by beta and gamma-secretase inhibitors. Eur J Pharmacol. 2005;1:1–15. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2005.02.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Wong GT, Manfra D, Poulet FM, et al. Chronic treatment with the gamma-secretase inhibitor LY-411,575 inhibits beta-amyloid peptide production and alters lymphopoiesis and intestinal cell differentiation. J Biol Chem. 2004;13:12876–12882. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M311652200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Vredenburgh JJ, Desjardins A, Herndon JE, et al. Phase II trial of bevacizumab and irinotecan in recurrent malignant glioma. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;4:1253–1259. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-2309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Poulsen HS, Grunnet K, Sorensen M, et al. Bevacizumab plus irinotecan in the treatment patients with progressive recurrent malignant brain tumours. Acta Oncol. 2008;48:52–58. doi: 10.1080/02841860802537924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Bergers G, Hanahan D. Modes of resistance to anti-angiogenic therapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2008;8:592–603. doi: 10.1038/nrc2442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]