Abstract

Covalent functionalization of pristine graphene poses considerable challenges due to the lack of reactive functional groups. Herein, we report a simple and general method to covalently functionalize pristine graphene with well-defined chemical functionalities. It is a solution-based process where solvent-exfoliated graphene was treated with perfluorophenylazide (PFPA) by photochemical or thermal activation. Graphene with well-defined chemical functionalities was synthesized and the resulting materials were soluble in organic solvents or water depending on the nature of the functional group on PFPA.

Keywords: Graphene, Azides, Covalent functionalization, Photochemistry

Graphene, a material having a two-dimensional atomic layer of sp2 carbon, has emerged as a nanoscale material with a wide range of unique properties.1-3 In order to realize the many potential applications that graphene can offer, the availability of graphene with well-defined and controllable surface and interface properties is of critical importance. Despite the numerous studies on the properties and potentials of graphene, robust methods for producing chemically functionalized graphene are still lacking.4,5 The most common method for the covalent functionalization of graphene employs graphene oxide (GO),6 which is prepared by treating graphite particles with strong acids.7 The oxidation process produces various oxygen-containing species, the nature and density of which are difficult to control.

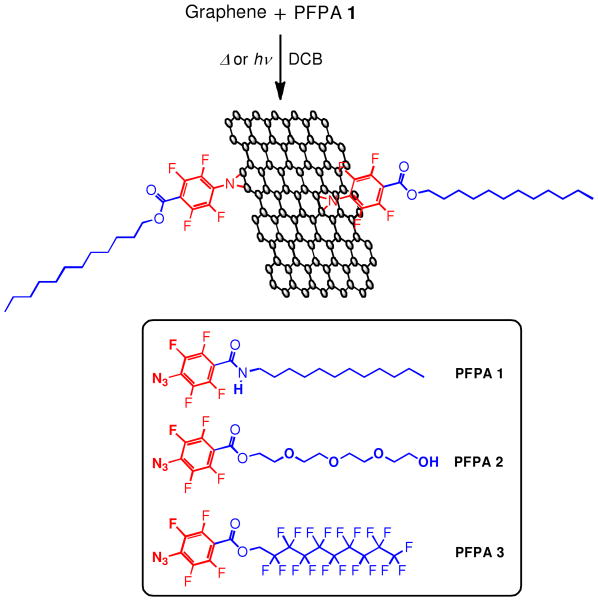

Covalent functionalization of pristine graphene poses considerable challenges due to its lack of reactive functional groups. Herein, we report a simple and general method for the covalent functionalization of pristine graphene. The approach is based on perfluorophenylazide (PFPA),8,9 which upon photochemical or thermal activation, is converted to the highly reactive singlet perfluorophenylnitrene that can subsequently undergo C=C addition reactions with the sp2 C network in graphene to form the aziridine adduct. We have confirmed the covalent bond formation between PFPA and graphene using X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy.10,11 By controlling the functional group on the PFPA (Scheme 1), graphene with well-defined chemical functionalities can be prepared in a single step using a simple solution-based process.

Scheme 1.

Functionalization of pristine graphene with PFPA.

PFPAs bearing alkyl (1), ethylene oxide (2), and perfluoroalkyl groups (3) (Scheme 1) were synthesized and used in this study (see Supporting Information for detailed synthesis and characterization of the compounds). These functional groups were chosen to impact the solubility and surface energy of the resulting graphene. Pristine graphene was prepared by exfoliating graphite in o-dichlorobenzene (DCB), a procedure that has been shown to produce graphene flakes in high yield.12 Sonication of graphite in DCB followed by centrifugation gave a well-dispersed graphene solution, which was collected and used in the subsequent reactions. These graphene flakes consisted primarily of four to five layers of graphene and thin graphite, as indicated by Raman spectroscopy and AFM.10 Covalent functionalization of graphene was accomplished by either thermal or photochemical activation. The thermal reactions were carried out by heating the graphene flakes with PFPA 1, 2 or 3 in DCB at 90 °C for 72 h. For the photochemical reactions, the graphene solution was mixed with PFPA 1, 2 or 3, sonicated for 10 min, and the resulting solution was irradiated under ambient conditions with a 450-W medium pressure Hg lamp for 60 min. In both cases, a large excess of PFPA compound was used to ensure complete functionalization of graphene. The product was then centrifuged and washed extensively with DCB and acetone to remove excess reagents, and was dried in vacuum.

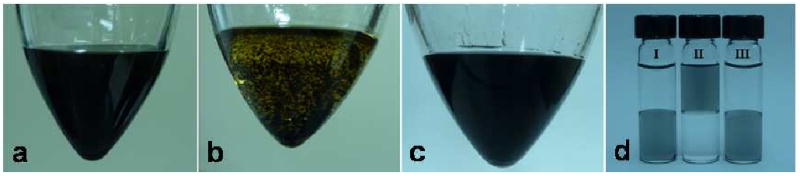

After graphene was functionalized with PFPA 1 and PFPA 3, the products were soluble in DCB, and homogeneous solutions were obtained (Figures 1a, 1c). In the reaction of PFPA 2 with graphene, however, the mixture was no longer homogeneous in DCB after the reaction. The product precipitated from the solution and was insoluble in DCB (Figure 1b). In fact, the product, after isolation from the reaction mixture and purification, was soluble in water instead (II, Figure 1d). On the other hand, the products functionalized with PFPA 1 and PFPA 3 were soluble in DCB and not in water (I and III, Figure 2c). These observations were strong evidence that graphene was indeed functionalized with the corresponding PFPA derivative. The solubility of graphene was thus drastically altered as a result of the chemical functionalization, and the functionalized graphene products dispersed well in the corresponding solvents. The solutions were stable, and no precipitates were observed after the solutions were set at ambient conditions for over 24 h.

Figure 1.

Reaction mixture after graphene was treated with PFPA a) 1, b) 2, and c) 3 by thermal reaction. d) Graphene functionalized with PFPA 1 (I), 2 (II), and 3 (III) in the mixed solvents of water (top layer) and DCB (bottom layer).

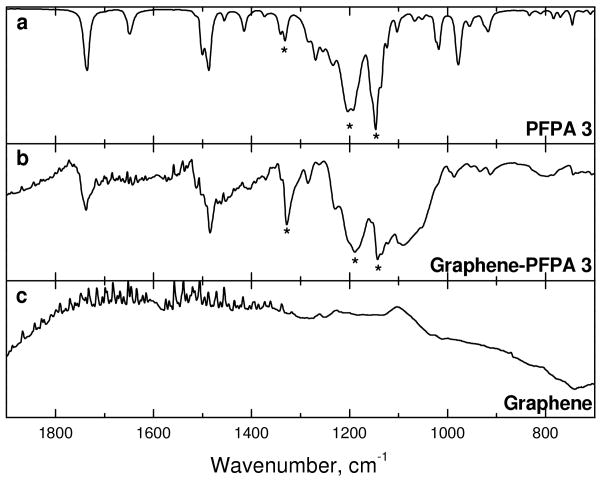

Figure 2.

FT-IR spectra of a) PFPA 3, b) PFPA 3-functionalized graphene, and c) pristine graphene.

The successful functionalization of graphene was further confirmed by FT-IR spectroscopy. Figure 2b shows the IR spectrum of the graphene functionalized with PFPA 3. The intense absorption bands at 1340 cm-1 and 1140-1200 cm-1 in PFPA 3 (marked with *, Figure 2a) are the axial CF2 stretching and asymmetric CF2 stretching vibrations, respectively.13 These fingerprints, as well as the ester absorption at 1730 cm-1, were observed in the graphene functionalized with PFPA 3 (Figure 2b). These peaks were absent in the pristine graphene that had not been functionalized (Figure 2c). Taken together, the results demonstrate that the graphene was indeed functionalized with PFPA 3.

In conclusion, we have developed a simple, general, and powerful method to derivatize pristine graphene using PFPAs. The functionalization was a solution-based process, carried out by thermal or photochemical activation. The functional group on the PFPA introduced well-defined chemical functionalities and rendered the resulting graphene soluble in organic solvents or in water. The method developed is readily applicable to different forms of graphene regardless of its size, shape, or configuration. The ability to control the chemical functionalities, to fine-tune the solubility and surface properties of graphene greatly enhances the processability of graphene-based materials. The functional groups can be furthermore derivatized with additional molecules and materials, opening up a myriad of opportunities in grapheme-based materials synthesis and nanodevice fabrication.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Oregon Nanoscience and Microtechnologies Institute (ONAMI) and ONR under the contract N00014-08-1-1237, and NIH (2R15GM066279, R01GM080295).

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available: General Instrumentations, experimental section and synthesis of PFPAs. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.Geim AK, Novoselov KS. Nat Mater. 2007;6:183–191. doi: 10.1038/nmat1849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Geim AK. Science. 2009;324:1530–1534. doi: 10.1126/science.1158877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Allen MJ, Tung VC, Kaner RB. Chem Rev. 2010;110:132–145. doi: 10.1021/cr900070d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Park S, Ruoff RS. Nat Nanotech. 2009;4:217–224. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2009.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Loh KP, Bao QL, Ang PK, Yang JX. J Mater Chem. 2010;20:2277–2289. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dreyer DR, Park S, Bielawski CW, Ruoff RS. Chem Soc Rev. 2010;39:228–240. doi: 10.1039/b917103g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hummers WS, Offeman RE. J Am Chem Soc. 1958;80:1339. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Leyva E, Platz MS, Persy G, Wirz J. J Am Chem Soc. 1986;108:3783–3790. doi: 10.1021/ja00284a049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yan M. Chem Eur J. 2007;13:4138–4144. doi: 10.1002/chem.200700317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu LH, Zorn G, Castner DG, Solanki R, Lerner MM, Yan M. J Mater Chem. 2010;20:5041–5046. doi: 10.1039/C0JM00509F. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu LH, Yan M. Nano Lett. 2009;9:3375–3378. doi: 10.1021/nl901669h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hamilton CE, Lomeda JR, Sun Z, Tour JM, Barron AR. Nano Lett. 2009;9:3460–3462. doi: 10.1021/nl9016623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Frey S, Heister K, Zharnikov M, Grunze M, Tamada K, Colorado R, Graupe M, Shmakova OE, Lee TR. Isr J Chem. 2000;40:81–97. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.