Abstract

Cigarette smoking during pregnancy is a preventable risk factor associated with maternal and fetal complications. Bupropion is an antidepressant used successfully for smoking cessation in non-pregnant patients. Our goal is to determine whether it could benefit the pregnant patient seeking smoking cessation. The aim of this investigation was to determine the role of human placenta in the disposition of bupropion and its major hepatic metabolite, OH-bupropion. The expression of efflux transporters P-gp and BCRP was determined in placental brush border membrane (n = 200) and revealed a positive correlation (p < 0.05). Bupropion was transported by BCRP (Kt 3 μM, Vmax 30pmol/mg protein/min) and P-gp (Kt 0.5 μM, Vmax 6 pmol/mg protein*min) in placental inside out vesicles (IOVs). OH-bupropion crossed the dually-perfused human placental lobule without undergoing further metabolism, nor was it an efflux substrate of P-gp or BCRP. In conclusion, our data indicate that human placenta actively regulates the disposition of bupropion (via metabolism, active transport), but not its major hepatic metabolite, OH-bupropion.

Keywords: placenta, p-glycoprotein, breast cancer resistance protein, bupropion, smoking

I. Introduction

Cigarette smoking during pregnancy has been associated with spontaneous abortion, placental pathology, preterm labor, low birth weight, stillbirth, sudden infant death syndrome, and childhood developmental problems [1]. Approximately 13% of mothers report smoking during the last 3 months of pregnancy [2], and many find it hard to stop or reduce smoking without the aid of medication. The benefits of smoking cessation during pregnancy include significant increase in birth weight and reduction in risk of preterm birth, as well as long term health benefits to both mother and child [3].

Currently, there is no approved medical therapy for smoking cessation during pregnancy. Occasionally health care providers recommend the use of nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) for those pregnant women who desire to quit smoking and fail other non-pharmacotherapeutic interventions. However, maternal exposure to nicotine has also been associated with risk to the developing fetus and newborn. Prenatal exposure to nicotine in animals was associated with blunted newborn respiratory response and increased rate of death [4]; anxiety, hyperactivity, and cognitive impairment in offspring [5]; and vasoconstriction related to decreased uteroplacental blood flow [6]. In humans, congenital malformations were higher among women who used NRT (patch, gum, or inhaler) during the first trimester than with nonsmokers [7]. Due to concern over safety of the developing fetus exposed to NRT, the goal of investigations in our laboratory is to evaluate an alternative to NRT for smoking cessation during pregnancy.

Bupropion is an antidepressant used successfully for smoking cessation in non-pregnant patients [8]. Accordingly, bupropion may also offer therapeutic benefit for smoking cessation in pregnant patients. However, its safety as a medication to be used during pregnancy remains unclear. Bupropion is labeled as Category C by the US Food and Drug Administration (i.e., data from animal models revealed adverse effects and there are not adequate studies in humans), but potential benefits may warrant its use during pregnancy despite potential risks [9].

Preclinical investigations in our laboratory on the biodisposition of bupropion by human placenta revealed that it crosses from the maternal to fetal circulation [10], and that it is metabolized by placental tissue [11]. Placental transfer of bupropion from the maternal to fetal circulation was approximately 20% [10]. This is less than the 30–40% reported transfer of nicotine which diffuses freely across the placental tissue [12],[13],[14]. The lower placental transfer of bupropion could be explained, in part, by the activity of placental efflux transporters. We have demonstrated that efflux transporters P-glycoprotein (P-gp) and Breast Cancer Resistance Protein (BCRP) have an active role in the efflux of their substrates across placental apical membrane [15]. Bupropion may be a P-gp substrate, as suggested by its stimulation of ATP hydrolysis by P-gp expressing membranes [16]. However, a direct determination of its transport by P-gp and/or other transporters expressed in placental apical membrane has not been reported to date.

An earlier report from our laboratory provided evidence that bupropion is metabolized by placental tissue during its perfusion [11]. The major metabolites of bupropion (threo- and erythro-hydrobupropion) formed by the placental tissue were distinct from the major hepatic metabolite (OH-bupropion), suggesting the placenta has a unique role in regulating the metabolic fate of bupropion. However, since bupropion is extensively metabolized to OH-bupropion, with plasma metabolite levels exceeding those of the parent compound [17], this active metabolite will be present in the circulation of pregnant patients receiving bupropion for treatment. Thus, concern over potential fetal exposure to OH-bupropion should be taken into consideration and the role of the placenta in its biodisposition warrants further investigation.

Taken together, the goals of this investigation were to determine the role of the placenta in the active regulation (metabolism, efflux transport) of OH-bupropion disposition compared to its parent compound, bupropion. Information obtained will be necessary for evaluation the extent of fetal exposure to bupropion and OH-bupropion, and consequently the safety of bupropion as an alternative medication for smoking cessation therapy in pregnant patients.

2. Material and Methods

2.1 Chemicals

All chemicals were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO) unless otherwise mentioned. The murine monoclonal antibodies C219 and BXP-21 were purchased from Signet Laboratories (Dedham, MA). Actin (C-2) mouse monoclonal antibodies and goat antimouse horseradish peroxidase-conjugated antibody were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. (Santa Cruz, CA). [14C]-hydroxybupropion (specific activity, 56.9 mCi/mmol) was custom-synthesized by Synthese AptoChem Inc (Montreal, Canada). [3H]-bupropion (specific activity, 4 Ci/mmol) was custom-synthesized by PerkinElmer Life and Analytical Sciences Custom Synthesis Group. [3H]-antipyrine (specific activity, 20 Ci/mmol) was purchased from American Radiolabeled Chemicals Inc (St. Louis, Missouri).

2.2 Clinical Material

Term human placentas (37–41 weeks) obtained from uncomplicated pregnancies were included in the study. A staff of trained research nurses was responsible for transporting the placentas immediately after delivery to our laboratory according to a protocol approved by the Institutional Review Board of UTMB.

2.3 Preparation of Placental Brush Border Membrane Vesicles

Placental brush border membrane vesicles from human placenta were prepared using a protocol modified from Ushigome et al. [18] and previously described in our laboratory [19]. Affinity chromatography was used to enrich the proportion of inside out vesicles (IOVs) [20]. Vesicle composition (brush border membrane) was confirmed by alkaline phosphatase assay, and inside-out configuration was determined by acetycholinesterase assay [19].

Vesicles were aliquoted and immediately stored at −80°C until use. ATP-dependent transport activity was verified an aliquot from each placental preparation, and those with low or no detectible ATP-dependent transport after thawing were excluded from the study. For experiments using multiple samples, apool was prepared using membrane preparations of 60 placentas obtained from uncomplicated term pregnancies. The large pool size reduces the confounding variable of inter-individual variation in the activity of transporters, and provides multiple and long-term use of the same lot of membranes.

2.4 Determination of P-gp and BCRP Protein Levels by Western Blot

The brush–border membranes were prepared as described above. The total protein concentration in all samples was determined by detergent-compatible Bradford protein assay (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA) using bovine serum albumin (10 to 100 μg total protein) as a standard.

Western blot quantification of P-gp protein expression was carried out using 7.5% SDS/polyacrylaminde gel electrophoresis. The amount of total placental apical membrane protein loaded on each well was 10 μg. At the end of electrophoresis, the gel was electroblotted on nitrocellulose membranes overnight at 4 °C and a constant potential of 25 V. Blots were probed with anti-P-gp mouse monoclonal antibodies (mAb C219) or anti-BCRP mouse monoclonal antibodies (mAb BXP-21) diluted 1:200 and secondary goat anti-mouse horseradish peroxidase-conjugated antibodies diluted 1:1000. Detection of the protein bands was carried out by spot densitometry and digital imaging of the enhanced chemiluminescence spots. The amount of expressed β-actin was used to normalize the amount of P-gp and BCRP in each loaded sample on the gel. A positive control consisted of human P-gp and BCRP membranes (Gentest Corporation).

2.5 Active Transport by Placental P-gp and BCRP

The direct measurement of transport was determined by measuring [3H]-bupropion or [14C]-OH-bupropion uptake into human placental IOVs. The protocol for the uptake assay is based on that for P-gp substrate, paclitaxel, described previously [19]. Each reaction was carried out in SHT buffer (10 mM HEPES-Tris, 250 mM sucrose) containing 4mM MgCl2 10 mM creatine phosphate, 100 μg/ml creatine phosphokinase, either 2 mM ATP or 3 mM NaCl, and placental BBMVs at a concentration of 0.05 μg/μL (7 μg total protein), in duplicates. The reaction was initiated by the addition of [3H]-bupropion or [14C]-OH-bupropion, at a final concentration ranging from 0.05 to 3 μM unless otherwise indicated. The reaction, carried out at 37°C, was terminated after 1 minute by the addition of 1 ml ice cold buffer, and vesicles were isolated using rapid filtration by a Brandel Cell Harvester using Whatman glass fiber filter strips (pore size 0.7 μM). The amount of radiolabeled drug retained was measured using liquid scintillation analysis, active transport was calculated as the difference in the presence and absence of ATP plus P-gp- or BCRP-selective inhibitor. P-gp-mediated transport (TP-gp) was measured in the presence and absence of P-gp-selective inhibitor, verapamil (600 μM) [21]. BCRP-mediated transport (TBCRP) was measured in the presence and absence of BCRP-selective inhibitor, 25 nM KO143 [22]. Kt and Vmax were determined by the least-squares fit of the data to the Michaelis-Menten equation. The reciprocal of radioligand uptake (1/uptake) was plotted vs the reciprocal of radioligand concentration in the incubation medium (1/c) for each experiment. The Kt and Vmax values for each experiment were obtained from the X and Y-intercepts, respectively, and pooled together to calculate the mean ± SEM.

2.6 Stimulation of P-gp and BCRP ATPase Activity by Bupropion

The interaction of bupropion with ABC transporters P-gp and BCRP was confirmed by stimulation of ATP hydrolysis in membranes expressing P-gp (Gentest) and BCRP (Solvo) by a protocol described in the product insert. Reactions were carried out in low-binding 96-well plates (Corning Costar, NY, USA). The reaction mixtures, in a final volume of 60 μl, contained 50mM Tris–Mes buffer (pH 6.8), 40μg P-gp membranes, bupropion (final concentration ranging 1–1000 uM), and 4mM Mg-ATP. After pre-warming at 37 °C for 3 min, the reactions were initiated by the addition of Mg-ATP. Verapamil and sulfasalazine served as positive control for stimulation of P-gp and BCRP ATPase, respectively. For each reaction, identical incubations containing 100mM orthovanadate, an inhibitor of ATP hydrolysis by ABC transporters, served as control for baseline ATPase activity. ATPase activity was quantified by determining the increase in Pi concentration that was subtracted from the activity generated in the presence of orthovanadate from the activity generated without orthovanadate to yield vanadate-sensitive ATPase activity.

2.7 Transplacental Transfer of OH-bupropion

The technique of dual perfusion of a placental lobule was used as previously described in our laboratory [23] and originally by Miller et al., [24]. Each placenta was perfused for an initial control period of 1 hour for determination of baseline viability and functional parameters (described below). Perfusion was terminated if: fetal arterial pressure exceeded 50 mmHg, volume loss in fetal circuit exceeded 2 ml/h, or if the pO2 difference between fetal vein and artery <60 mmHg (indicating inadequate perfusion overlap between the two circuits). The experimental period of 4 hours was initiated by the addition of OH-bupropion and 1.5 μCi of its [14C]-isotope to the maternal reservoir (final concentration of 470 ng/ml [25]. The non-ionizable, lipophillic marker compound antipyrine (AP) 20 μg/ml and its [3H]-isotope (1.5 μCi) were co-transfused with OH-bupropion to account for interplacental variations and to normalize the transfer of OH-bupropion. The perfusion system was used in its closed—closed configuration (re-circulation of perfusion medium).

Binding of [14C]-OH-bupropion to glassware, teflon and tygon type of tubing utilized in the perfusion system was determined by re-circulating drug in the model system in the absence of a placenta. Binding of [14C]-OH-bupropion to glassware and tubing was negligible.

Samples from the maternal artery and fetal vein, in 0.5 ml aliquots, were taken at 0, 5, 10, 15, 30, 45, 60, 90, 120, 150, 180, 210, and 240 minutes and the amount of radioactivity was determined in each sample by liquid scintillation spectrometry using both [3H] and [14C]- channels simultaneously (1900TR; Packard Instruments, Shelton, CT). The concentration of OH-bupropion in all samples was calculated after correcting for the specific activity as previously reported [23]. At the end of experiment, the perfused area was dissected from the adjoining placental tissue, weighed, and homogenized in a volume of saline equal to four times its weight. One ml of 1 M NaOH was added to 1 ml of the homogenate and the samples were incubated for 12 hours at 60°C in the dark to allow for luminescence decay. Scintillation cocktail (4 ml) was added to each sample and the concentration of each drug was determined.

The effects of OH-bupropion on placental tissue were evaluated by determining placental functional (human chorionic gonadotropin [hCG] release), and viability parameters (oxygen transfer and consumption) [23]. The concentration of hCG was determined by an IRMA kit (Diagnostics Production Corp, Los Angeles, CA). The amount of hCG released in control period (in absence of test drug) was set at 100% and samples assayed for hCG during the 4-hour experimental period were expressed as percentage of initial value. Control placentas were perfused for the 4 hour experimental period in the absence of OH-bupropion for comparison. Oxygen transfer and consumption were determined in samples collected every 15 minutes from both circuits and immediately analyzed for pH, pO2, and pCO2 by a blood gas analyzer (Instrumentation Laboratory, Lexington, MA).

2.8 Metabolism of OH-bupropion

At the end of the 4-hour experimental period, 20 ml of medium was collected from each of the maternal and fetal reservoirs, and 10g of the perfused tissue was excised, homogenized and used for extraction. Samples (2mL) were combined with 6mL of acetonitrile, shaken for 5min, and then centrifuged for 15min at 4°C. The supernatant was collected and dried under air stream at 40°C. The residue was reconstituted using 80uL of mobile phase, and 50uL was injected into HPLC system.

The detection of metabolites of OH-bupropion (if any) was achieved using an HPLC-Radioactive detector. The HPLC system consisted of a Waters 1525 Binary HPLC Pump, a 717 plus autosampler, β-RAM Model 4 (IN/US systems, Tampa, FLA), and controlled by Empower™2 chromatography Data Software (Waters, Milford, Mass). The mobile phase consisted of methanol and 10 mM ammonium acetate (pH=5.2, adjusted by 0.1M acetic acid). Elution was accomplished by isocratic elution with flow rate 1.0mL/min. The separation was achieved using a Waters Symmetry C18 column (150 × 4.6mm, 5μm) connected to a Phenomenex C18 guard column (4×3.0mm) at ambient temperature.

2.9 Statistical Analysis

Data are plotted as mean ± SEM unless otherwise indicated. Statistical significance was determined using a paired student’s t-test. A probability of p < 0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance.

3. Results

3.1 P-gp and BCRP expression in human placenta

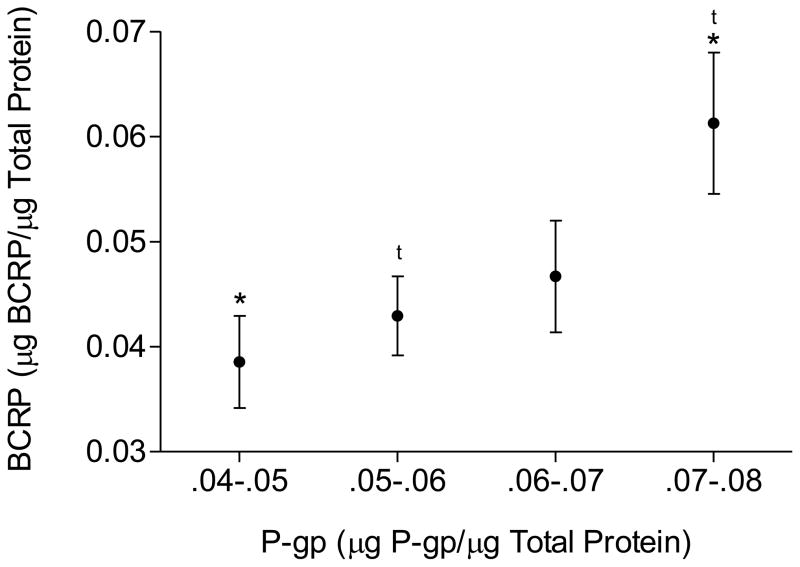

P-gp protein expression was determined in 200 individual samples of human placental brush border membranes. There was a positive correlation between P-gp and BCRP protein expression in human placenta (Figure 1, p < 0.001).

Figure 1.

P-gp and BCRP protein expression in human placentas as determined by western blot. The immunoblot (10 μg/lane) was probed with the monoclonal antibody C219 for P-gp, and monoclonal antibody BXP-21 for BCRP. Immunoreactive protein bands detected by immunoblotting were analyzed by densitometry. Expression was determined as a proportion of the total amount of β-actin present per lane. There was a positive correlation between protein expression of P-gp and BCRP (*, t = p<0.05).

3.2 Bupropion and OH-Bupropion transport by P-gp and BCRP

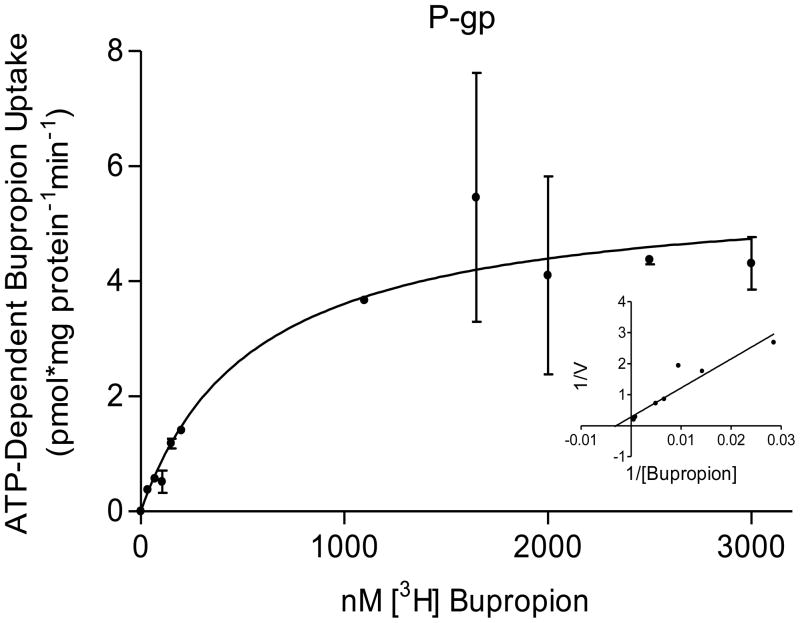

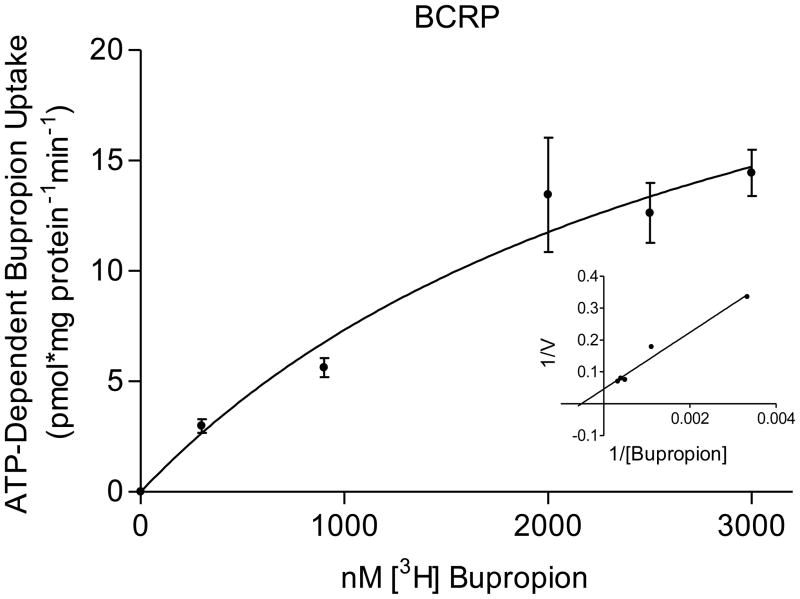

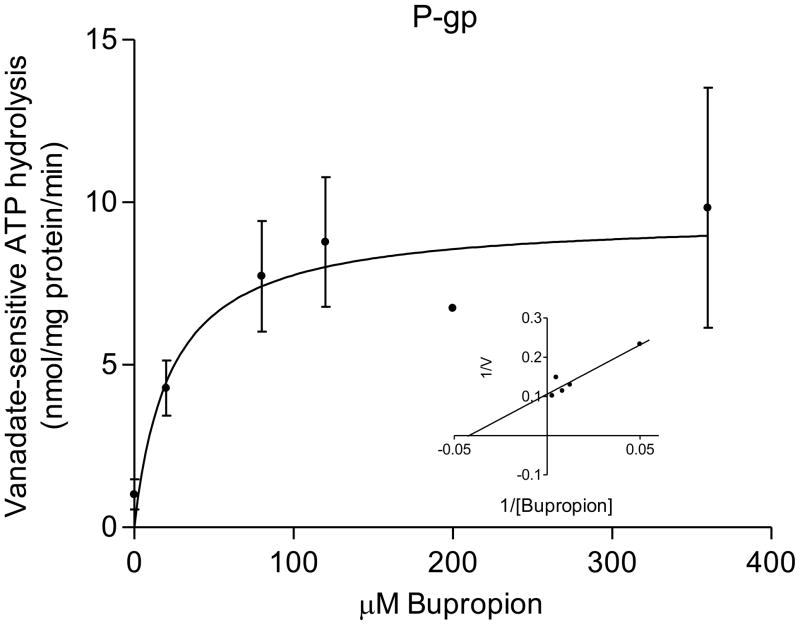

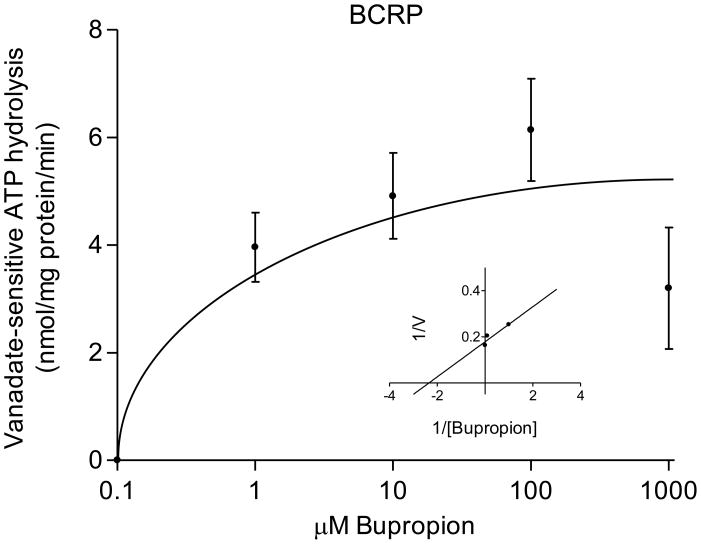

The transport of bupropion was ATP-dependent and partially inhibited in the presence of 600μM verapamil (selective for P-gp mediated transport) and 25nM KO143 (selective for BCRP). The kinetic parameters of its transport were: P-gp, Kt = 0.5 ± 0.2 μM bupropion and Vmax = 6 ± 0.7 pmol/mg protein/min; BCRP, Kt = 3 ± 2 μM bupropion; and Vmax = 30 ± 13 pmol/mg protein/min (Figure 2). The interaction of bupropion with P-gp and BCRP was confirmed by stimulation of ATP hydrolysis in insect cell membranes transfected with human P-gp or BCRP. Bupropion stimulated ATP hydrolysis by both P-gp and BCRP in a concentration-dependent manner (Figure 3). Bupropion stimulated ATPase activity with a Km of 23 ± 19 μM and Vmax of 9.5 ± 1.6 nmoles Pi/mg protein*min by P-gp; and a Km of 0.6 ± 0.4 μM and Vmax of 6 ± 0.8 nmoles Pi/mg protein*min by BCRP.

Figure 2.

Bupropion transport by P-gp and BCRP. Bupropion displayed ATP-dependent transport into placental IOVs by both P-gp and BCRP. (A) P-gp displayed apparent Kt of 0.5 ± 0.2 μM and Vmax = 6 ± 0.7 pmol/mg protein*min for bupropion transport (B) BCRP displayed apparent Kt of 3 ± 2 μM and Vmax = 30 ± 13 pmol/mg protein*min for bupropion transport, with Lineweaver-Burk plot (inset). Data are presented as mean ± SEM of 4–8 experiments in a pool of 60 placentas.

Figure 3.

Bupropion stimulation of ATP hydrolysis by P-gp and BCRP. Stimulation of ATPase activity, as measured by inorganic phosphate release in the presence and absence of ATPase inhibitor sodium orthovanadate (100 μM), was detected in baculovirus-transfected insect cells expressing human P-gp (A) and BCRP (B). Bupropion stimulated ATP hydrolysis by both P-gp and BCRP in a concentration-dependent manner, confirming that bupropion interacts with P-gp and BCRP.

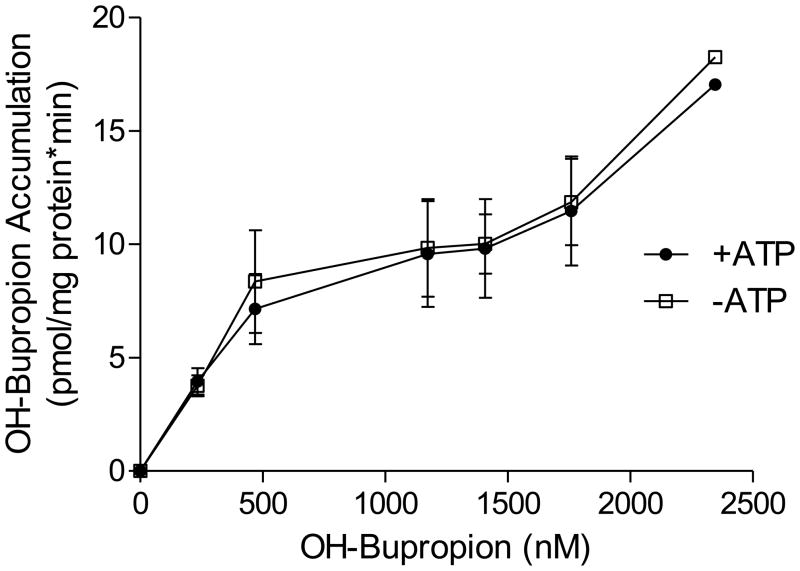

In contrast to bupropion, OH-bupropion accumulation in placental IOVs was similar in the presence and absence of ATP (Figure 4). Thus, OH-bupropion did not exhibit ATP-dependent transport by brush border membrane vesicles, ruling it out as a potential substrate of the ATP-dependent transporters P-gp and BCRP.

Figure 4.

OH-bupropion transport by placental IOVs. ATP-dependent transport of OH-Bupropion was determined by its accumulation in placental IOVs in the presence and absence of an ATP-regenerating system. The accumulation was similar in the presence and absence of ATP, indicating OH-bupropion is not a transported substrate of P-gp or BCRP in human placenta brush border membrane. The role of non-ATP-dependent transporters in OH-bupropion distribution cannot be ruled out at this time. Data are presented as mean ± SEM of 4 experiments in a pool of 60 placentas.

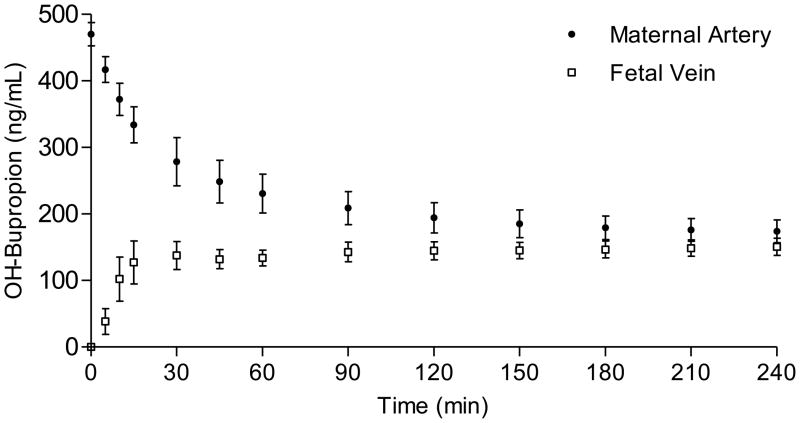

3.3 Transplacental Transfer of OH-Bupropion

[14C]-OH-bupropion was added to the maternal circuit at an initial concentration of 470 ± 17 ng/ml and was perfused using the closed-closed configuration for a period of 4 hours. OH-bupropion crossed the placenta in the maternal-to-fetal direction and appeared in the fetal circuit within 5 minutes of perfusion (Figure 5). The concentration of OH-bupropion in the fetal circuit at the end of the experimental period was 151 ± 13 ng/ml, which represents 32 ± 3% of its initial concentration in maternal circuit. Values for placental viability and functional parameters were unchanged during OH-bupropion perfusion and were within the range of control placentas.

Figure 5.

Placental transfer of OH-bupropion. [14C]-OH-bupropion added to the maternal circuit at initial concentration of 470 ± 17 ng/ml was perfused using closed-closed configuration for 4 hours. OH-bupropion appeared in the fetal circuit within 5 minutes of perfusion. The concentration of OH-bupropion in the fetal circuit at the end of experiment reached 151 ± 13 ng/ml, which represents 32 ± 3% of its initial concentration in maternal circuit.

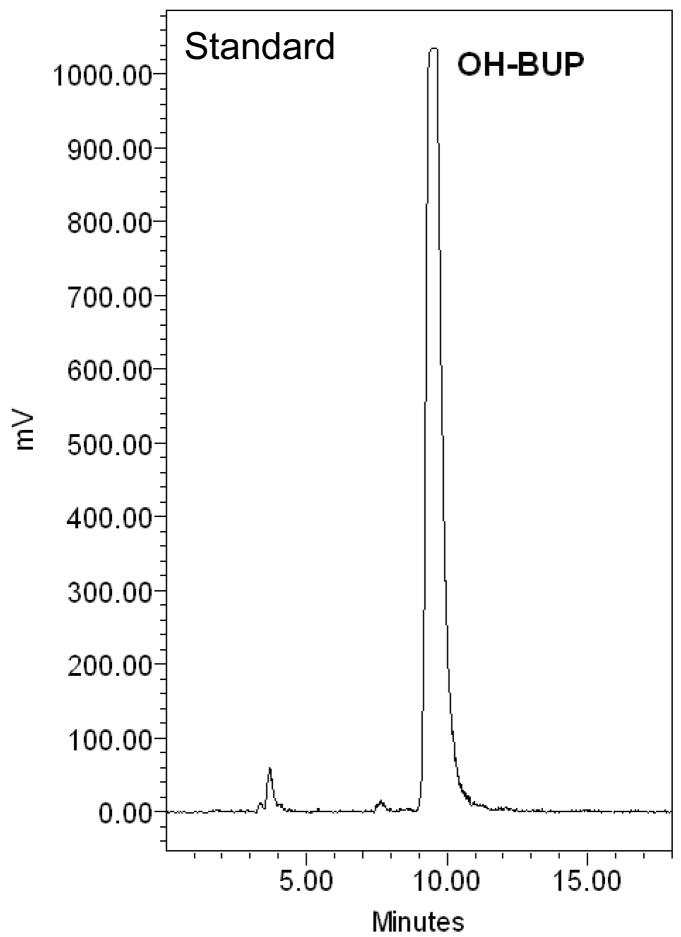

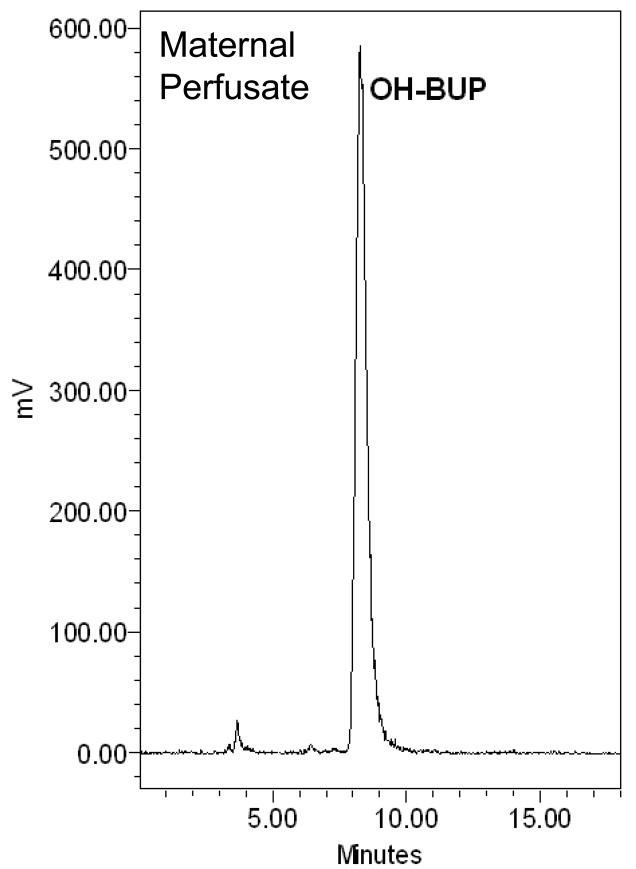

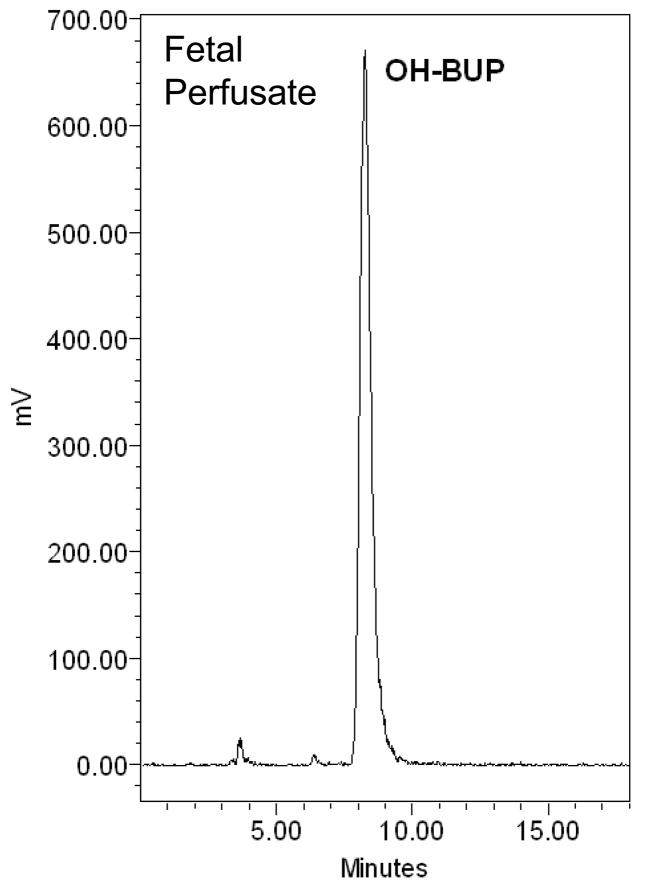

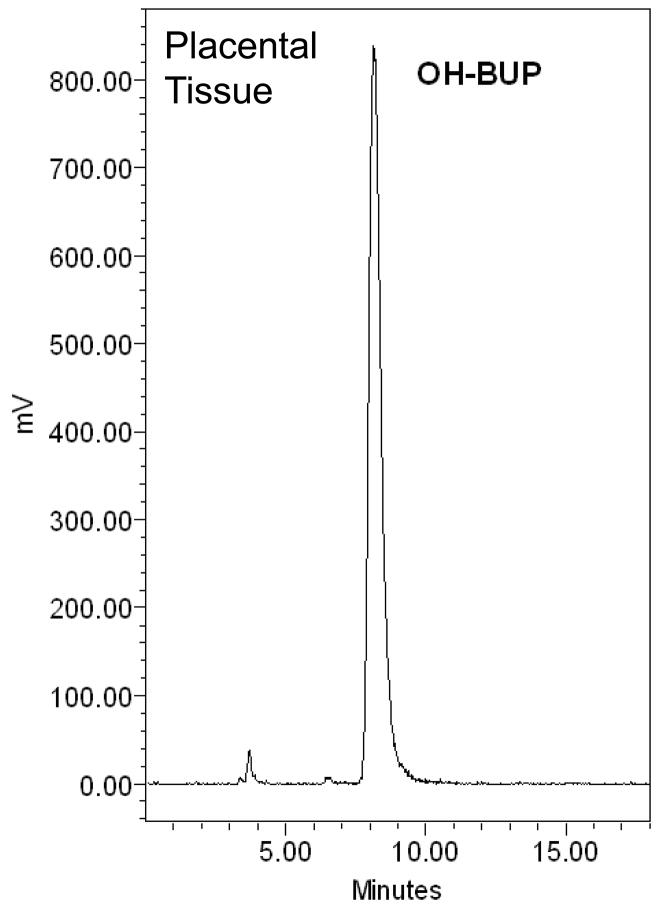

3.4 Metabolism of OH-Bupropion by Placental Tissue

The amount of [C14]-OH-bupropion in the perfusion medium was determined using a radioactive detector attached online to an HPLC system. Extraction of OH-bupropion for HPLC analysis was achieved with 80% recovery. The elution profile revealed one peak eluted at 10 minutes representing [C14]-OH-bupropion (standard compound shown in Figure 6.A). The single peak representing OH-bupropion was detected in both maternal and fetal circuits and the placental tissue after 4 hours of perfusion (Figure 6.B, C, D). These data indicate that OH-bupropion crosses the placenta without undergoing biotransformation by placental enzymes during the 4 hours of perfusion.

Figure 6.

OH-bupropion (OH-BUP) metabolism by placental tissue during perfusion. OH-bupropion was not metabolized by the placental tissue during 4 hours of perfusion. HPLC-Radioactive chromatograms of [C14]-OH-bupropion perfused in human placenta displaying A) [C14]-OH-bupropion (OH-BUP) standard, B) maternal perfusate at 240 minutes, C) fetal perfusate at 240 minutes, and D) sample of perfused placental tissue at 240 minutes.

4. Discussion

The goal of this investigation was to determine human placental biodisposition of OH-bupropion, including metabolism and efflux by active transporters, in comparision to its parent compound bupropion. Previous reports from our laboratory and others revealed that bupropion is extensively metabolized by placental tissue [11] and appears to be a substrate of placental efflux transporters [16]. This led us to hypothesize that the placenta “actively regulates” the maternal-fetal distribution of bupropion. To date, the placental permeability of its active hepatic metabolite OH-bupropion, which plasma concentration may exceed that of bupropion, remained unknown.

Due to their localization and active role in efflux at the placental brush border membrane [15], the trophoblast transporters P-gp and BCRP were characterized by their protein expression and interaction with bupropion. P-gp protein expression positively correlated with that of BCRP in human placenta. It has been previously reported that P-gp substrates are capable of inducing its gene expression [26]. Thus, the evidence that P-gp and BCRP have overlapping substrates and positive correlation of protein levels suggest that their gene expression may regulated similarly in human placenta.

The ATP-dependent transport of bupropion by P-gp and BCRP was determined using placental brush border IOVs with inhibition by both verapamil (P-gp selective inhibitor) and KO143 (BCRP selective inhibitor). In our system, bupropion has higher affinity for transport by P-gp (as evidenced by lower Kt), while BCRP exhibits greater total transport activity (Vmax). These data indicate that P-gp and BCRP may work in parallel to extrude bupropion from the placenta, but with distinct roles. P-gp may be the first line of defense in fetal protection by transporting bupropion from the fetal-to-maternal direction (its high affinity represents transport occurs at low bupropion concentrations). BCRP may serve as a second line of defense when bupropion concentrations are elevated in the placental tissue.

In contrast to bupropion, ATP-dependent transport of OH-bupropion was not detected, i.e., the accumulation of the compound by placental IOVs was unchanged in the presence and absence of ATP. Since both P-gp and BCRP require ATP binding/hydrolysis as a source of energy for active transport, lack of ATP-dependence in OH-bupropion accumulation rules out the involvement of these transporters in its placental disposition. Furthermore, OH-bupropion crossed the placenta without undergoing metabolism by the placental tissue. The urinary glucuronide conjugates of OH-bupropion have been previously identified [27]. However, the single peak detected in placental tissue, maternal, and fetal perfusate matched that of the standard compound, OH-bupropion, indicating that placental glucuronidation of this compound during perfusion did not occur.

The concentration of OH-bupropion detected in the fetal circuit following perfusion, reaching approximately 32% of its initial concentration in the maternal circuit, is similar to the placental transfer of freely-diffusible compounds nicotine and antipyrine (30–40% transfer) [12],[13],[14]. Taken together, the lack of involvement of active efflux transport or metabolism of OH-bupropion suggests that, unlike the parent compound bupropion, the placenta does not actively regulate the biodisposition of this metabolite. Additionally, since OH-bupropion is present in the circulation of patients treated with bupropion [17], its fetal exposure in pregnant patients is likely and should be taken into consideration.

Evaluation of pharmacotherapy for the pregnant patient seeking smoking cessation involves weighing the risk to benefit ratio of bupropion (and its major metabolites). Although its use during pregnancy is restriced to FDA Category C, up to 30% of physicians have been reported to discuss pharmacotherapy for smoking cessation during pregnancy, with up to 10% of pregnant women reporting use of some form of it [28]. Therefore, the plausibility of bupropion being described to pregnant patients for smoking cessation warrants investigation of its safety. Although OH-bupropion did not appear to adversely affect placental viability and functional parameters, the toxicity of this active metabolite cannot be ruled out. Hydroxybupropion demonstrates significant pharmacologic activity, and it has been suggested that it has a role in the neurological side effects associated with bupropion [29],[30]. On the other hand, if this major metabolite has a significant role in the therapeutic effects of bupropion, it may promote abstinence from smoking in pregnant patients. If exposure to bupropion or its metabolites indeed promotes abstinence from smoking during pregnancy, it may pose less risk of fetal toxicity than the contents of cigarette smoke which includes thousands of compounds including carcinogens [31].

In conclusion, this investigation has demonstrated that the role of the placenta differs in its regulation of biodisposition between bupropion and its metabolite, OH-bupropion. P-gp and BCRP, coexpressed in human placental brush border membrane, are involved in the fetal-to-maternal efflux of bupropion. Furthermore, in contrast to bupropion, its major active metabolite OH-bupropion does not appear to be a substrate of placental metabolic enzymes or brush border efflux transporters. Future investigations should evaluate the genetic and environmental factors associated with bupropion pharmacokinetics in the pregnant patient, and their relation to its safety and efficacy as a smoking cessation agent.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Perinatal Research Division for their assistance, and the Publication, Grant, & Media Support of the UTMB Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology. Supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse Grant R01DA024094 to TN.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Sarah J. Hemauer, Email: sjhemaue@utmb.edu.

Svetlana L. Patrikeeva, Email: svpatrik@utmb.edu.

Xiaoming Wang, Email: xiawang1@utmb.edu.

Doaa R. Abdelrahman, Email: doredaab@utmb.edu.

Gary D.V. Hankins, Email: ghankins@utmb.edu.

Mahmoud S. Ahmed, Email: maahmed@utmb.edu.

Tatiana N. Nanovskaya, Email: tnnanovs@utmb.edu.

References

- 1.Rogers JM. Tobacco and pregnancy. Reprod Toxicol. 2009 Sep;28(2):152–60. doi: 10.1016/j.reprotox.2009.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.England LJ, Grauman A, Qian C, Wilkins DG, Schisterman EF, Yu KF, Levine RJ. Misclassification of maternal smoking status and its effects on an epidemiologic study of pregnancy outcomes. Nicotine Tob Res. 2007 Oct;9(10):1005–13. doi: 10.1080/14622200701491255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lumley J, Oliver SS, Chamberlain Cl. Interventions for promoting smoking cessation during pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004:CD001055. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001055.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Slotkin TA. If nicotine is a developmental neurotoxicant in animal studies, dare we recommend nicotine replacement therapy in pregnant women and adolescents? Neurotoxicology and Teratology. 2008;30:1–19. doi: 10.1016/j.ntt.2007.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pauly JR, Slotkin TA. Maternal tobacco smoking, nicotine replacement and neurobehavioural development. Acta Paediatrica. 2008;97:1331–1337. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2008.00852.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Xiao D, Huang X, Yang S, Zhang L. Direct effects of nicotine on contractility of the uterine artery in pregnancy. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 2007;322:180–185. doi: 10.1124/jpet.107.119354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Morales-Suarez-Varela MM, Bille C, Christensen K, Olsen J. Smoking habits, nicotine use, and congenital malformations. Obstet and Gynecol. 2006;107:51–57. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000194079.66834.d5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hurt RD, Sachs DP, Glover ED, Offord KP, Johnston JA, Dale LC, et al. A comparison of sustained-release bupropion and placebo for smoking cessation. New England Journal of Medicine. 1997;337:1195–1202. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199710233371703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.ZYBAN® (bupropion hydrochloride) Sustained-Release Tablets Prescribing Information. [Last accessed April 14, 2010.];The US Food and Drug Administration website. 2010 Available at: http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2009/020711s032s033lbl.pdf.

- 10.Earhart AD, Patrikeeva S, Wang X, Reda Abdelrahman D, Hankins GD, Ahmed MS, Nanovskaya T. Transplacental transfer and metabolism of bupropion. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2010 May;23(5):409–16. doi: 10.1080/14767050903168424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang X, Abdelrahman DR, Zharikova OL, Patrikeeva SL, Hankins GD, Ahmed MS, Nanovskaya TN. Bupropion metabolism by human placenta. Biochem Pharmacol. 2010 Jun 1;79(11):1684–90. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2010.01.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sastry BVR, Owens LK. Regional and differential sensitivity of umbilico-placental vasculature to hydroxyltryptamine, nicotine and ethyl alcohol. Trophoblast Res. 1987;2:289–304. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pastrakuljic A, Schwartz R, Simone C, Derewlany LO, Knie B, Koren G. Transplacental transfer and biotransformation studies of nicotine in the human placental cotyledon perfused in vitro. Life Sci. 1998;63:2333–2342. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(98)00522-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nekhayeva IA, Nanovskaya TN, Pentel PR, Keyler DE, Hankins GD, Ahmed MS. Effects of nicotine-specific antibodies, Nic311 and Nic-IgG, on the transfer of nicotine across the human placenta. Biochem Pharmacol. 2005 Nov 25;70(11):1664–72. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2005.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hemauer SJ, Patrikeeva SL, Nanovskaya TN, Hankins GD, Ahmed MS. Role of human placental apical membrane transporters in the efflux of glyburide, rosiglitazone, and metformin. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010 Apr;202(4):383.e1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2010.01.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang JS, Zhu HJ, Gibson BB, Markowitz JS, Donovan JL, DeVane CL. Sertraline and its metabolite desmethylsertraline, but not bupropion or its three major metabolites, have high affinity for P-glycoprotein. Biol Pharm Bull. 2008 Feb;31(2):231–4. doi: 10.1248/bpb.31.231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bondarev ML, Bondareva TS, Young R, Glennon RA. Behavioral and biochemical investigations of bupropion metabolites. Eur J Pharmacol. 2003 Aug 1;474(1):85–93. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(03)02010-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ushigome F, Koyabu N, Satoh S, Tsukimori K, Nakano H, Nakamura T, et al. Kinetic analysis of P-glycoprotein-mediated transport by using normal human placental brush-border membrane vesicles. Pharm Res. 2003;20(1):38–44. doi: 10.1023/a:1022290523347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hemauer SJ, Patrikeeva SL, Nanovskaya TN, Hankins GD, Ahmed MS. Opiates inhibit paclitaxel uptake by P-glycoprotein in preparations of human placental inside-out vesicles. Biochem Pharmacol. 2009 Nov 1;78(9):1272–8. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2009.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Awasthi S, Singhal S, Srivastava SK, Zimniak P, Bajpai KK, Saxena M, et al. Adenosine triphosphate-dependent transport of doxorubicin, daunomycin, and vinblastine in human tissues by a mechanism distinct from the P-glycoprotein. J Clin Invest. 1994;93(3):958–965. doi: 10.1172/JCI117102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tsuruo T, Lida H, Tsukagoshi S, Sakurai Y. Overcoming of vincristine resistance in P388 leukemia in vivo and in vitro through enhanced cytotoxicity of vincristine and vinblastine by verapamil. Cancer Res. 1981;41(5):1967–1972. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Benyahia B, Huguet S, Declèves X, et al. Multidrug resistance-associated protein MRP1 expression in human gliomas: chemosensitization to vincristine and etoposide by indomethacin in human glioma cell lines overexpressing MRP1. J Neurooncol. 2004;66(1–2):65–70. doi: 10.1023/b:neon.0000013484.73208.a4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nanovskaya TN, Deshmukh S, Brooks M, Ahmed MS. Transplacental transfer and metabolism of buprenorphine. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2002;300(1):26–33. doi: 10.1124/jpet.300.1.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Miller RK, Wier PJ, Zavislan J, Maulik D, Perez-D’Gregorio R, et al. Human dual placental perfusions: criteria for toxicity evaluations. In: Heindel JJ, Chapin RE, editors. Methods in toxicology. 1993. pp. 205–45. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hsyu PH, Singh A, Giargiari TD, Dunn JA, Ascher JA, Johnston JA. Pharmacokinetics of bupropion and its metabolites in cigarette smokers versus nonsmokers. J Clin Pharmacol. 1997 Aug;37(8):737–43. doi: 10.1002/j.1552-4604.1997.tb04361.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang X, Meng M, Gao L, Liu T, Xu Q, Zeng S. Permeation of astilbin and taxifolin in Caco-2 cell and their effects on the P-gp. Int J Pharm. 2009;378(1–2):1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2009.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Petsalo A, Turpeinen M, Tolonen A. Identification of bupropion urinary metabolites by liquid chromatography/mass spectrometry. Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom. 2007;21(16):2547–54. doi: 10.1002/rcm.3117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Oncken CA, Kranzler HR. What do we know about the role of pharmacotherapy for smoking cessation before or during pregnancy? Nicotine Tob Res. 2009 Nov;11(11):1265–73. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntp136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Martin P, Massol J, Colin JN, Lacomblez L, Puech AJ. Antidepressant profile of bupropion and three metabolites in mice. Pharmacopsychiatry. 1990;23:187–194. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1014505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sanchez C, Hyttel J. Comparison of the effects of antidepressants and their metabolites on reuptake of biogenic amines and on receptor binding. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 1999;19:467–489. doi: 10.1023/A:1006986824213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Talbot P. In vitro assessment of reproductive toxicity of tobacco smoke and its constituents. Birth Defects Res C Embryo Today. 2008 Mar;84(1):61–72. doi: 10.1002/bdrc.20120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]