Abstract

This study is a retrospective, case-control study involving 535 preterm infants examining the roles of sequence polymorphisms in genes that mediate host immune responses to bacterial infection in newborn infants. A total of 49 single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in 19 candidate genes including inflammatory cytokines (IL6, IL10, IL1B, TNF), cytokine receptors (IL1RN), toll-like receptors (TLR2, TLR4, TLR5) and cell surface receptors (CD14) were genotyped. Subjects were stratified into 3 groups (sepsis, suspected sepsis, control). The data were analyzed using a family-based transmission disequilibrium test. We found that birth weight, gestational age, duration of rupture of membranes, and presence of clinical chorioamnionitis were strongly associated with sepsis. Polymorphisms in TLR2 (rs3804099), TLR5 (rs5744105), IL10 (rs1800896), and PLA2G2A (rs1891320) genes were associated with sepsis. Allelic variants in PLA2G2A and TLR2 were associated with Gram-positive infections, while IL10 was associated with Gram-negative infections (p< 0.05). We conclude allelic variations in PLA2G2A, TLR2, TLR5, and IL10 may moderate the predisposition to sepsis in preterm infants.

INTRODUCTION

Neonatal sepsis is a major cause of morbidity and mortality among newborn infants occurring in 1% of term and up to 20% of very-low-birth-weight (VLBW) infants (1–3). The mortality rate varies from 3% to 50% in early-onset sepsis, and up to 40% in late-onset sepsis (2). Susceptibility factors for newborn infants to sepsis include maternal and environmental exposures, immune status, and inflammatory responses. These interacting factors can be modified by variation among individuals in gene function or expression that may have significant clinical implications.

The neonate is a unique host immunologically. Only a few studies have characterized the immune response of neonates to bacterial infection (4–8). Studies of the innate and adaptive immune responses in newborn infants, and in particular extremely preterm neonates, have suggested that there are both impaired neutrophil function and unique cytokine responses (5,6,8).

The pathophysiology of sepsis involves highly complex interactions between invading microorganisms, the innate and adaptive immune systems of the host, and multiple downstream events leading to organ dysfunction and death (9). Altered cellular signaling due to circulating cellular mediators contributes to dysregulation of immunity, tissue repair, and cellular stress responses (10). The typical initial response to bacterial infection is the recognition of pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) via cell surface receptors. Toll-like receptor-2 (TLR-2) appears to be involved in recognition of Gram-positive bacteria, and TLR-4 in the recognition of Gram-negative bacteria (11). IL1 receptor-associated kinase (IRAK) undergoes autophosphorylation following interaction with the TLR-MyD88 complex (12). Ultimately, this cascade results in the expression of specific cytokines. Proinflammatory mediators (IL-1B, IL-6, TNF-A and LTA) activate host defenses against pathogens. IL-1 receptor antagonist (IL-1RA) antagonizes the proinflammatory action of IL-1B. IL-10 is also a potent anti-inflammatory mediator, limiting the inflammatory response, thus preventing an excessive reaction which may itself cause organ damage and cell death (13).

Studies in twins suggest that host genetic factors significantly contribute to interindividual variation in susceptibility to infections (14,15). Genetic association studies have suggested that one or more candidate genes have a role in pathogenesis of sepsis (14,16). Recent evidence also supports the view that gene-environment interactions result in certain patients having heightened susceptibility to neonatal sepsis and provide insights into mechanisms of disease development (16–18).

Identification of genetic variations in the genes involved in bacterial-induced cellular response and those involved in the pathogenesis of sepsis may allow the development of new diagnostic tools, improved classification of sepsis, and more accurate predictors of patient outcomes. In this study, we examined the relationship between genetic variants in 19 genes involved in host responses to bacterial infection and sepsis in newborn infants.

METHODS

This study is a retrospective, case-control study involving preterm infants admitted to the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit of the University of Iowa Children’s Hospital from 2000–2007. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board for Human Research at University of Iowa. Parental consent was required for inclusion.

Subjects

Three groups of preterm infants (less than 37 weeks gestation) were defined in this study. The infected group (79 infants) consisted of those infants with symptoms and signs of sepsis: temperature instability, respiratory compromise, (increased oxygen requirement, respiratory distress, apnea, cyanosis), cardiovascular compromise (bradycardia, tachycardia, poor perfusion, hypotension), neurologic changes (hypotonia, lethargy, seizures), gastrointestinal compromise (feeding intolerance, abdominal distension, vomiting). These infants had positive cultures for blood, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), or urine and were treated with antibiotics for ≥7 days. The suspected sepsis group (254 infants) consisted of infants who had clinical signs of sepsis and received antibiotic treatment for ≥7 days but had sterile cultures for blood, CSF, or urine. The control group (202 infants) consisted of infants who never had a positive culture for blood, CSF, or urine and received no antibiotic therapy for ≥ 7 days at any time during their hospital stay. Exclusion criteria in this study removed infants with birth defects and from pregnancies affecting twins and higher multiples. Clinical and outcome data were abstracted from a Neonatal Intensive Care Database and the infants medical records. DNA was collected as part of an ongoing study (IRB-approved) of diseases in newborn infants. DNA was extracted from cord blood or buccal swabs for infants and from venous blood or buccal swabs for the parents. One or both parents were enrolled in this study along with their infants.

Candidate genes

Nineteen candidate genes were selected for analysis including genes involved in the pathogenesis of inflammation and sepsis as well as in immune regulation. These genes encode pattern-recognition receptors (CD14, TLR2, TLR4, TLR5), intracellular signaling proteins (MyD88, IRAK1), proinflammatory cytokines (IL1B, IL1RN, IL6, TNF, LTA), antiinflammatory cytokines (IL10, IL10RA), chemokines (IL-8), bactericidal-permeability increasing protein (BPI), angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE), mannose binding lectin-2 (MBL2), and phospholipase A2 (PLA2G2A). All are located on autosomes except IRAK1which is located on the X chromosome.

Most of the SNPs represented functional variants or tagging SNPs characterized through the International HapMap Project. Eight SNPs had been implicated in sepsis predisposition in other studies: IL10 (rs1800872, rs1800896), IL1B (rs1143643), IL6 (rs1800795), MBL2 (rs5030737, rs7096206), CD14 (rs2569190), BPI (rs4358188) (17,19,20,21). The genes and SNPs investigated are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

List of Genes and SNPs.

| Gene | Chromosome | SNP | Gene | Chromosome | SNP |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IL10 | 1 | rs1800872 | IL6 | 7 | rs1800795 |

| rs1800896 | rs1554606 | ||||

| rs2222202 | TLR4 | 9 | rs1927911 | ||

| TLR5 | 1 | rs5744105 | rs2149356 | ||

| PLA2G2A2 | 1 | rs1891320 | rs4986791 | ||

| rs1891321 | rs1554973 | ||||

| rs955587 | MBL2 | 10 | rs1838065 | ||

| rs2307246 | rs5030737 | ||||

| IL1B | 2 | rs1143643 | rs7096206 | ||

| rs1143634 | rs930506 | ||||

| rs1143627 | IL10RA | 11 | rs2256111 | ||

| IL1RN | 2 | rs419598 | rs2229113 | ||

| rs315952 | rs11216666 | ||||

| MyD88 | 3 | rs7744 | rs17121510 | ||

| rs6853 | ACE | 17 | rs4968779 | ||

| IL8 | 4 | rs4073 | rs4293 | ||

| TLR2 | 4 | rs11938228 | rs4341 | ||

| rs3804099 | rs4351 | ||||

| rs3804100 | rs4267385 | ||||

| rs1585110 | rs8066114 | ||||

| CD14 | 5 | rs2569190 | BPI | 20 | rs1341023 |

| LTA | 6 | rs2229094 | rs5743507 | ||

| TNF | 6 | rs1799964 | rs4358188 | ||

| rs1800629 | IRAK1 | X | rs1059703 | ||

| IL6 | 7 | rs1880243 |

Genotyping

Genotyping for single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) markers was performed using the TaqMan genotyping system on an ABI 7900HT (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Following PCR amplification, allele determination was detected by end-point analysis using SDS software. Forty-nine SNPs in the 19 genes were genotyped. Genotyped data were entered into a Progeny database (Progeny Software, LLC, South Bend, IN, USA) for generation of datasets for analysis.

Statistical analysis

Non-random allele inheritance was assessed by transmission disequilibrium test (TDT) as implemented in the software Family Based Association Test (FBAT) (22,23). Alleles and genotypes at each marker were tested for association with sepsis. Haplotype analysis was performed for genes that had more than one SNP genotyped. Differences among the three study groups were evaluated for the following characteristics: 1) gender, type of delivery, duration of rupture of membranes, and clinical chorioamnionitis using chi-square tests and 2) gestational age, birth weight, days on mechanical ventilation, and total days on oxygen using tests of analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Tukey’s adjustment for multiple tests at the p=0.05 level. A multivariable logistic regression was conducted to adjust for gestational age in the TDT analysis. Principal component analysis was used to define a phenotype for TDT that was a composite of correlated data. Data are presented as mean with minimum and maximum values. P-values less than 0.05 were considered significant. Because this study is both hypothesis testing and hypothesis generating, less stringent p-values are also of interest. The statistical software SAS (SAS 9.1.3, SAS institute Inc, Cary, NC) was used.

RESULTS

Population Characteristics

A total of 535 newborn infants were enrolled in the study. Demographic and clinical characteristics of the three groups are described in Table 2.

Table 2.

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of the Study Groups.

| Characteristic | Sepsis (n=79) | Suspected (n=254) | Control (n=202) | p-value* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gestational age (weeks) (min, max) | 27.5 (23,36) | 31.7 (23,36) | 33.6 (27,36) | <0.0001 |

| Birthweight (grams) (min, max) | 1169 (328,3440) | 1858 (376,4400) | 2120 (606,4026) | <0.0001 |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 59 ** | 129 | 111 | 0.0009 |

| Female | 20 | 125 | 91 | |

| Race | ||||

| Caucasian | 58 | 205 | 176 ** | 0.001 |

| African-American | 10 ** | 17 | 4 | |

| Others (Asian, | 5 | 8 | 9 | |

| Not reported | 6 | 24 | 13 | |

| Ethnic status | ||||

| Non Hispanic or Latino | 63 | 185 | 143 | 0.92 |

| Hispanic or Latino | 7 | 17 | 13 | |

| Not reported | 9 | 52 | 46 | |

| Type of delivery | ||||

| C-section delivery | 57 ** | 135 | 109 | 0.007 |

| Vaginal delivery | 22 | 119 | 93 | |

| Rupture of membranes (ROM) | ||||

| Spontaneous | 30 | 102 | 72 | 0.55 |

| Artificial | 36 | 112 | 99 | |

| No data | 13 | 40 | 31 | |

| Duration of ROM | ||||

| < 6 hr | 14 ** | 38 | 31 | 5E-06 |

| 6–24 hr | 1 | 36 | 39 ** | |

| 25–48 hr | 0 | 6 | 7 | |

| > 48 hr | 13 ** | 40 ** | 10 | |

| No PROM | 30 | 66 | 49 | |

| No Data | 21 | 68 | 66 | |

| ROM (hours) (min, max) | 40.7 (0,408) | 83.2 (0,1488) | 31.8 (0,912) | 0.04 |

| Clinical chorioamnionitis | ||||

| Yes | 10 ** | 21 ** | 4 | 0.002 |

| No | 49 | 172 | 143 ** | |

| Unknown | 8 | 16 | 8 | |

| No data | 12 | 45 | 47 | |

| Ventilation days (min, max) | 34.2 (0,106) | 7.7 (0,104) | 1.6 (0,51) | <0.0001 |

| Supplemental oxygen days (min, max) | 72.6 (1,175) | 25.0 (0,258) | 8.6 (0,70) | <0.0001 |

p-values reported are from analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Chi-Square tests. ANOVA is used for gestational age, birth weight, days on ventilation, days on oxygen. All sepsis groups are significantly distinct from each other using Tukey’s adjustment for multiple tests at the p=0.05 level. For duration of ROM, only the suspected sepsis group is significantly distinct from the other sepsis groups using Tukey’s adjustment for multiple tests at the p=0.05 level. Other variables used Chi-Square tests to determine significant differences between the frequencies within the 3 sepsis subgroups.

Indicates the subgroup frequency that is overrepresented.

The mean gestational age and birth weight for infants with proven sepsis were 27.5 wk and 1169 g respectively. All infants with proven sepsis were preterm. The majority of subjects were Caucasian by parental report. Seventy-one infants were classified as late-onset sepsis (>72 hr), and eight infants had early-onset sepsis (<72 hr). The average age for the first episode of sepsis was 25 days. Forty one infants had positive blood cultures, 25 infants had positive blood and urine cultures, 12 infants had positive urine cultures, and one infant had a positive CSF culture. Forty-nine percent had a single episode with at least one positive culture, 29% of infants had 2 episodes, and 22% had 3 or more episodes during their hospital stay. These episodes were separated in time by at least 3 days, and infants started a new course of antibiotics for each episode. The predominant presenting clinical features of infection were increased apnea episodes (42%), increased oxygen requirement or increased need for assisted ventilation (15 %), and gastrointestinal signs (12%). In the infected group, one infant died due to a sepsis-related complication.

We found that birth weight and gestational age (GA) were strongly associated with risk of sepsis (p< 0.0001). The infection rate was inversely related to birth weight. Similarly, the infection rate was inversely related to GA. Seventy-three percent of the infants were ≤28 weeks, 14% of infants between 29–32 weeks, 13% of infants > 32 weeks. Many low-birth-weight neonates have complex medical problems and prolonged hospitalization. The risk of infection is increased in infants with increasing duration of ventilation. Infants with sepsis had a significantly longer duration of mechanical ventilation than those without sepsis (p< 0.0001). Birth weight and gestational age were inversely correlated with days on oxygen and days on ventilation (Table 2).

Pathogen Distribution

Gram-positive organisms (60%) were isolated more frequently than Gram-negative organisms (30%) in our population. Coagulase-negative staphylococcus (CONS) (50%) was the most commonly isolated organism from blood cultures, and Enterococcus species (25%) from urine cultures. The organisms causing sepsis in this investigation are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Distribution of the pathogens in 79 infants with sepsis (166 episodes)*

| Number | |

|---|---|

| Gram Positive Infection | |

| Coagulase negative Staphylococcus | 55 |

| Enterococcus | 29 |

| Staphylococcus aureus | 11 |

| Beta-hemolytic Streptococcus | 3 |

| Alpha-hemolytic Streptococcus | 1 |

| Gram Negative Infection | |

| Klebsiella species | 18 |

| Escherichia coli | 12 |

| Pseudomonas species | 6 |

| Serratia species | 2 |

| Citrobacter species | 5 |

| Haemophilus influenzae | 1 |

| Proteus mirabilis | 1 |

| Others§ | 5 |

| Fungal | |

| Candida (albican, rugosa, parapsilios) | 17 |

some patients had multiple episodes

Others included Enterobacter (cloacae, aerogenes), and Acinetobacter baumanii.

Maternal History

Mode of delivery, duration of rupture of membranes, and presence of clinical chorioamnionitis were significantly associated with sepsis (Table 2).

Analytic Results

TDT analysis of 49 SNPs in 19 genes showed that PLA2G2A (rs1891320), TLR2(rs3804099), TLR5 (rs5744105), and IL10 (rs1800896) were associated with neonatal sepsis (p< 0.05). In the suspected group, PLA2G2A (rs1891320) and IL10RA (rs11216666) showed p-values less than 0.05, with borderline significance for MBL2 (rs7096206) and IL6 (rs1800795) in the same group (p= 0.05). Haplotype analysis revealed no significant association with sepsis for the SNPs of PLA2G2A gene and TLR2 (p> 0.05). The allele frequencies of the significant polymorphisms were next analyzed among the study groups. Infants with sepsis did not show a significantly different frequency of any allele compared with the control group.

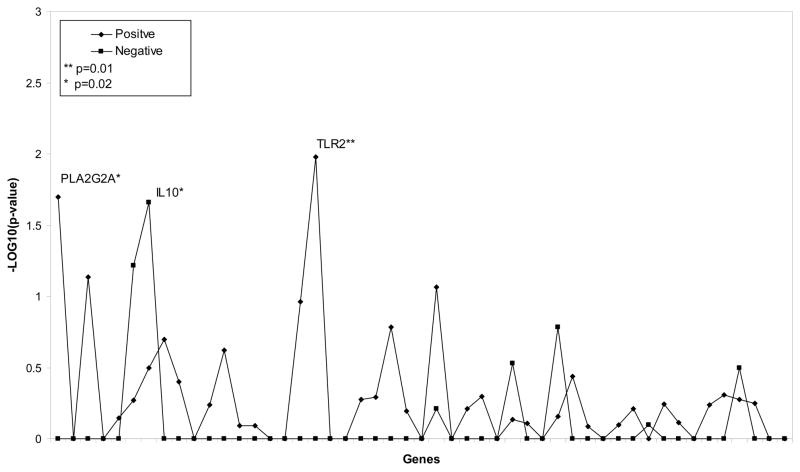

We further analyzed each SNP with respect to the type of bacterial infection. Using TDT, we found that allelic variation in IL10 (rs1800896) was significantly associated with Gram-negative infection (p= 0.02), while variations in TLR2 (rs3804099) and PLA2G2A (rs1891320) were associated with Gram-positive infection (p= 0.02, Figure 1). Allele frequency of the SNPs associated with Gram-positive and Gram-negative infections did not show any differences with the control group. Haplotype analysis of 2 variations in the TLR2 gene (rs3804099 and rs3804100) showed significant association with Gram-positive infections (p= 0.02). No other haplotype analysis yielded a significant association.

Figure 1.

SNPs Associated with Gram-positive (◆) and Gram-negative (■) infections.

** indicates p-values =0.01 and * indicates p-values of 0.02.

Analysis using spontaneous delivery as the phenotype revealed that the gene IL8 (rs4073) was significantly associated (p=0.004) with sepsis and this same SNP was also associated with the phenotype prematurity (p=0.03). When regression analysis using gestational age was done with sepsis as the affection status, none of the aforementioned SNPs showed association. However, variations in the IL10 gene (rs2222202; p=0.03) and the IL10RA gene (rs11216666; p=0.02) showed an association with gestational age.

In a final approach, we used principal components analysis to create another phenotype that was a combination of the four principal predictors of sepsis: gestational age (GA), birth weight (BW), the number of days on supplemental oxygen (DOO) and the number of days on the ventilator (DOV). The eigenvector (or direction of effect) created for all premature infants with data on the four principal predictors of sepsis is: −0.525, −0.467, +0.526, +0.479 for GA, BW, DOO and DOV respectively. The eigenvalue (strength of effect) for the first component was 3.04 and represented 76% of the variance. When performing principal components analysis on the 79 infants with sepsis, the eigenvalue was similar (3.21), the variance accounted for was similar (80%) and the eigenvector was similar in magnitude but opposite in direction (+0.521, +0.488, −0.526, −0.462 for GA, BW, DOO, and DOV respectively). When the principal component was calculated using all premature infants, TDT analysis identified a SNP in the MBL2 gene (rs1838065) with a p-value of 0.015 and together with rs5030737, a global haplotype p-value of 0.05. TDT analysis also identified a SNP in the TNF gene (rs1799964) with a p-value of 0.002 (T allele associated, 95 informative pedigrees) and a p-value of 0.003 for the genotype T/T (Figure 2). With the principal component calculated just on the infants with sepsis, TDT analysis identified 2 SNPs in the ACE gene (rs4341 and rs4351) with p-values of 0.02 and 0.04 respectively, with a haplotype p-value of 0.08.

Figure 2.

Four Phenotypes: a principal component of gestational age, birth weight, days on oxygen and days on ventilator for all infants (PrinComponent, ◆) and only for the 79 sepsis infants (SepsisPrinComp, ■), gestational age (Gest Age, ▲) and sepsis adjusted by gestational age (Gest Age Adj, ■). ** Three genes have p-values < 0.01: two for Principal Component (TNFA, p=0.003 and MBL2, p=0.01) and one for Gestational Age (BPI, p=0.008). Sepsis adjusted for gestational age was also significant for the same SNP in the MBL2 gene (p=0.01) but was not significant for raw Gestational Age. * Four other genes have p-values < 0.05: IL10, p=0.03; IL8, p=0.04; IL10RA, p=0.02; and ACE has 2 SNPs with p=0.02 and 0.04.

DISCUSSION

Despite the significant burden of sepsis, genetic association studies in newborn infants, especially in VLBW infants, are still limited in comparison to adults (20,24,25). This study used a candidate gene approach and, given the relatively large number of SNPs tested, was viewed as both hypothesis testing and hypothesis generating since the power to detect significant associations after accounting for multiple comparisons (p<0.001 would be the minimal significant p value under stringent testing) was limited by our sample size of just over 500 total cases. Less stringent p-values might be explored in the context of generating models to correlate clinical data and specific pathogens interactions. Large-scale population, careful study design, multi-center design, replication studies, repeated-confirmation are still needed to have accurate data. In this study, we identified a small number of genetic variations associated with sepsis in preterm infants.

The PLA2G2A gene is located on chromosome 1, and the protein it encodes mediates the hydrolysis of phospholipids. Group (G) IIA PLA2 is the most potent among mammalian secreted PLA2(s) against Gram-positive bacteria. Secreted phospholipase A2 enzyme (PLA2) is a mediator connecting innate and adaptive immunity and is upregulated in infections (26). sPLA2-IIA is transcriptionally induced by pro-inflammatory cytokines through the NF-kB pathway. Nevertheless, whether transcriptional synthesis of sPLA2- IIA is regulated by other signaling cascades has not been explored in detail (26). Elsbach and Weiss (27)found that GIIA PLA2, together with the bactericidal/permeability increasing protein kill Gram-negative bacteria. A number of prior studies have demonstrated in vitro and in vivo antibacterial properties associated with GIIA PLA2 (28,29). Our study shows that PLA2G2A rs1891320 was associated with Gram-positive sepsis. There is no data about the role of this specific SNP in PLA2G2A in infections in either neonatal or adult sepsis.

Toll-like receptors (TLRs) constitute a family of transmembrane proteins that recognize pathogen-associated molecular patterns. They play a fundamental role in innate immune responses. TLRs signal via a common pathway that leads to the expression of diverse inflammatory genes. Each TLR elicits specific cellular responses to pathogens using different intracellular adapter proteins. Recent studies have revealed the importance of the subcellular localization of TLRs in pathogen recognition and signaling (30). TLR signaling pathways are negatively regulated by a number of cellular proteins that attenuate inflammation. TLR2 is predominantly responsible for recognizing Gram-positive cell wall structures (31). Investigators have hypothesized that mutations in TLR2 could be associated with a diminished response to Gram-positive lipoproteins and place individuals at higher risk of Gram-positive infections (21). Sutherland and colleagues reported the association of TLR2 (rs4696480, T16933A) with the development of sepsis in adults (19). TLR5, which recognizes bacterial flagellin in Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria, plays an important role in mediating responses to this bacterial antigen through activating NF-kB and the release of proinflammatory cytokines (32). Studies suggest that TLR5 plays an important role in pulmonary epithelial responses and may increase susceptibility to pneumonia associated with flagellated organisms (33). Analysis of TLR5 (rs5744105) was significant in both sepsis and control groups. Hawn and colleagues (33)demonstrated that flagellated bacteria, but not nonflagellated bacteria, activate TLR5, indicating that flagellin is a specific ligand for TLR5. In our study, 23% of septic infants were infected with E. coli or P. aeruginosa, which are flagellated. In the control group, TLR5 had a p-value of 0.02. This finding raises the question as to whether TLR5 may play a role in preterm delivery, a pathologic process that is triggered in part by inflammatory pathways.

Our analysis of IL10 rs1800896 showed borderline significance (p= 0.05), while variation at position rs1800872 did not show significance. IL-10 is potent anti-inflammatory cytokine and a key regulator of immune response. Overproduction of either proinflammatory mediators or anti-inflammatory cytokines might lead to organ dysfunction and death (34). In sepsis, high IL-10 levels are associated with severity of infection in newborn infants (35,36). The IL10 gene 5′-flanking sequence has three SNPs upstream from the transcriptional start site, at positions −1082 (G/A: rs1800896), −819 (C/T), and −592 (C/A: rs1800872), that regulate IL10 expression (13). Because there is complete linkage disequilibrium between the polymorphisms at −592 and −819, the −819 variant was not evaluated. Baier et al (20)found an increased incidence of late-onset sepsis in VLBW infants with the IL10 rs1800896 AA genotype, while Treszl et al (24) found no association with susceptibility to sepsis in a small cohort of infants. Schaaf et al (37)in a study of septic shock showed that the IL10 (rs1800896) G allele is associated with increased IL-10 release, which could be a risk factor for septic shock in pneumococcal infection, while the IL10 (rs1800872) A allele is associated with lower stimulated IL-10 release and increased mortality.

The National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) Neonatal Research Network reported that Gram-negative bacteria continue to be the predominant pathogens associated with early-onset sepsis (38), while the vast majority of late-onset infections were caused by Gram-positive bacteria (1). In our study, we found that one IL10 polymorphism (rs1800896) was associated with Gram-negative infection, whereas TLR2 rs3804099 was associated with Gram-positive infections. A study done by Lorenz et al (21) demonstrated a link between a TLR2 rs5743708 polymorphism and severe staphylococcal infections. Sutherland et al. (19) examined another TLR2 SNP, TLR2 T-16933A (rs4696480), located 5′ of the TLR2 gene, in a cohort of patients with sepsis and found an association between the A allele and development of sepsis and Gram-positive cultures. Studies of the amino acid TLR2 Arg753Gln variant (rs5743708) (21,39) suggest that it may predispose individuals to certain Gram-positive infections. No data exist regarding the functional relevance of TLR2 rs3804099. Thus, overall, there is suggestive evidence that genetic variation in TLR2 might influence risks for sepsis, but future studies will need to clarify this potential relationship to determine if rs3804099 itself, or another SNP in association with it, play a causal role.

IL10RA rs11216666, IL6 rs1800795, and MBL2 rs7096206 were significant in the suspected sepsis group, but not the control group. IL6 is a pro-inflammatory cytokine associated with an increased occurrence of shock and death in septic patients. In our study IL6 rs1800795 showed borderline significance in the suspected sepsis group. A large meta-analysis (1323 subjects)to determine the association of the IL6 polymorphisms and the risk of sepsis in VLBW infants concluded that the available data are not consistent with more than a modest association (25).

Bactericidal/permeability increasing protein (BPI), found mainly in the azurophilic granules of neutrophils, plays an important role in the defense against Gram-negative infection and in resolution of endotoxin inflammatory reactions (40). Newborn neutrophils are deficient in BPI (5)and plasma levels tend to be lower in preterm infants (cord blood) than in full term infants (41). Our study did not show an association between the BPI polymorphism and susceptibility to sepsis. A reported association between a BPI polymorphism and sepsis in a pediatric population (42) suggests that examining BPI gene polymorphisms on a larger sample population of preterm and full term infants is indicated.

Since our study sample is defined as premature infants (< 37 weeks gestation) with sepsis, suspected sepsis or no sepsis, an important question is how to best adjust for gestational age. The condition of interest is sepsis, and perhaps the principal components method for defining phenotype is more appropriate since it incorporates degree of sepsis and seriousness of affection into the phenotype as demonstrated by the eigenvector values for days on ventilation and days on oxygen. The fact that most genes had some association with the phenotype of choice indicates that the inflammatory pathway may be involved but different underlying aspects of sepsis are being detected with differing methods. The availability of parental samples and the use of the TDT approach enabled us to eliminate or minimize the effect of ancestry on the results. Nevertheless, it remains possible that particular ancestral groups might have a greater or lesser contribution to the role of a specific SNP in sepsis.

In conclusion, this study of sepsis carried out an analysis of candidate genes in pathways regulating the immune response in a neonatal population. Our data demonstrated uncorrected associations between PLA2G2A (rs1891320), TLR2 (rs3804099), TLR5 (rs5744105) and IL10 (rs1800896) polymorphisms and sepsis. Our study is a step in the path of identification of host susceptibility to sepsis and will now require larger and more detailed gene/SNP combinations to be studied. Identification of relevant genetics risk factors can pave the way to a better understanding of pathophysiology and suggest new avenues for treatment and prevention.

Acknowledgments

Supported by NIH R01 HD052953-01, HD057192, March of Dimes #6 FY08 260 and #21 FY06 575. Dr. Abu Maziad was supported by a grant from the Egyptian Ministry of Higher Education

We thank the families who participated in the study; Susan Berends and Ligia Grindeanu for their help in data collection; research nurses Karen Johnson, Gretchen Cress, Laura Knosp, Nancy Krutzfield, and Ruthann Schrock; and the Murray laboratory group especially Keegan Kelsey, Diane Caprau, Cara Zimmerman, Emily Marcus, Susie McConnell, and Nancy Davin.

Abbreviations

- BPI

bactericidal/permeability increasing protein

- IRAK

interleukin-1 receptor-associated kinases

- LPS

lipopolysaccharides

- MyD88

myeloid differentiation protein 88

- PAMPs

pathogen-associated molecular patterns

- PLA

phospholipase A

- SNP

single nucleotide polymorphism

- TLR

toll-like receptor

- TNF

tumor necrosis factor

- VLBW

very low birth weight

References

- 1.Stoll BJ, Hansen N. Infections in VLBW infants: studies from the NICHD Neonatal Research Network. Semin Perinatol. 2003;27:293–301. doi: 10.1016/s0146-0005(03)00046-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Klein JO. Bacterial sepsis and meningitis. In: Remington JS, Klein JO, editors. Infectious Diseases of the Fetus and Newborn Infant. 5. W.B Saunders Co; Philadelphia: 2001. pp. 943–998. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stoll BJ, Hansen N, Fanaroff AA, Wright LL, Carlo WA, Ehrenkranz RA, Lemons JA, Donovan EF, Stark AR, Tyson JE, Oh W, Bauer CR, Korones SB, Shankaran S, Laptook AR, Stevenson DK, Papile LA, Poole WK. Late-onset sepsis in very low birth weight neonates: the experience of the NICHD Neonatal Research Network. Pediatrics. 2002;110:285–91. doi: 10.1542/peds.110.2.285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wolach B. Neonatal sepsis: pathogenesis and supportive therapy. Semin Perinatol. 1997;21(1):28–38. doi: 10.1016/s0146-0005(97)80017-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Levy O, Martin S, Eichenwald E, Ganz T, Valore E, Carroll SF, Lee K, Goldmann D, Thorne GM. Impaired innate immunity in the newborn: newborn neutrophils are deficient in bactericidal/permeability-increasing protein. Pediatrics. 1999;104:1327–33. doi: 10.1542/peds.104.6.1327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Levy O. Innate immunity of the human newborn: distinct cytokine responses to LPS and other Toll-like receptor agonists. J Endotoxin Res. 2005;11(2):113–6. doi: 10.1179/096805105X37376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Levy O. Innate immunity of the newborn: basic mechanisms and clinical correlates. Nature Reviews Immunology. 2007;7:379–390. doi: 10.1038/nri2075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wynn JL, Neu J, Moldawer LL, Levy O. Potential of immunomodulatory agents for prevention and treatment of neonatal sepsis. J Perinatol. 2009;29(2):79–88. doi: 10.1038/jp.2008.132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hotchkiss RS, Karl IE. The pathophysiology and treatment of sepsis. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:138–50. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra021333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cohen J. The immunopathogenesis of sepsis. Nature. 2002;420:885–91. doi: 10.1038/nature01326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Medzhitov R. Toll-like receptors and innate immunity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2001;1:135–45. doi: 10.1038/35100529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Janeway CA, Jr, Medzhitov R. Innate immune recognition. Annu Rev Immunol. 2002;20:197–216. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.20.083001.084359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moore KW, de Waal Malefyt R, Coffman RL, O’Garra A. Interleukin-10 and the interleukin-10 receptor. Annu Rev Immunol. 2001;19:683–765. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.19.1.683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Härtel C, Schultz C, Herting E, Göpel W. Genetic association studies in VLBW infants exemplifying susceptibility to sepsis-recent findings and implications for future research. Acta Paediatr. 2007;96(2):158–65. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2007.00128.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bhandari V, Bizzarro MJ, Shetty A, Zhong X, Page GP, Zhang H, Ment LR, Gruen JR. Familial and genetic susceptibility to major neonatal morbidities in preterm twins. Pediatrics. 2006;117(6):1901–6. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-1414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Harding D. Impact of common genetic variation on neonatal disease and outcome. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2007;92:408–413. doi: 10.1136/adc.2006.108670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Papathanassoglou ED, Giannakopoulou MD, Bozas E. Genomic variations and susceptibility to sepsis. AACN Adv Crit Care. 2006;17:394–422. doi: 10.4037/15597768-2006-4006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Arcaroli J, Fessler MB, Abraham E. Genetic polymorphisms and sepsis. Shock. 2005;24:300–312. doi: 10.1097/01.shk.0000180621.52058.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sutherland AM, Walley KR, Russell JA. Polymorphisms in CD14, mannose-binding lectin, and toll-like receptor-2 are associated with increased prevalence of infection in critically ill adults. Crit Care Med. 2005;33:638–44. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000156242.44356.c5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Baier RJ, Loggins J, Yanamandra K. IL-10, IL-6 and CD14 polymorphisms and sepsis outcome in ventilated very low birth weight infants. BMC Med. 2006;4:10. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-4-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lorenz E, Mira JP, Cornish KL, Arbour NC, Schwartz DA. A novel polymorphism in the toll-like receptor 2 gene and its potential association with staphylococcal infection. Infect Immun. 2000;68:6398–6401. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.11.6398-6401.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Horvath S, Xu X, Laird NM. The family based association test method: strategies for studying general genotype-phenotype associations. Eur J Hum Genet. 2001;9:301–306. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5200625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Laird NM, Horvath S, Xu X. Implementing a unified approach to family-based tests of association. Genet Epidemiol. 2000;19:S36–42. doi: 10.1002/1098-2272(2000)19:1+<::AID-GEPI6>3.0.CO;2-M. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Treszl A, Kocsis I, Szathmári M, Schuler A, Héninger E, Tulassay T, Vásárhelyi B. Genetic variants of TNF-[FC12]a, IL-1beta, IL-4 receptor [FC12]a-chain, IL-6 and IL-10 genes are not risk factors for sepsis in low-birth-weight infants. Biol Neonate. 2003;83:241–5. doi: 10.1159/000069484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chauhan M, McGuire W. Interleukin-6 (−174C) polymorphism and the risk of sepsis in very-low-birth-weight infants: meta-analysis. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2008;93:F427–9. doi: 10.1136/adc.2007.134205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jensen MD, Sheng W, Simonyi A, Johnson GS, Sun AY, Sun GY. Involvement of oxidative pathways in cytokine-induced secretory phospholipase A2-IIA in astrocytes. Neurochem Int. 2009;55:362–368. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2009.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Elsbach P, Weiss J, Franson RC, Beckerdite-Quagliata S, Schneider A, Harris L. Separation and purification of a potent bactericidal/permeability-increasing protein and a closely associated phospholipase A2 from rabbit polymorphonuclear leukocytes. J Biol Chem. 1979;254:11000–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Weinrauch Y, Elsbach P, Madsen L, Foreman A, Weiss J. The potent anti-Staphylococcus aureus activity of a sterile rabbit inflammatory fluid is due to a 14-kD phospholipase A2. J Clin Invest. 1996;97:250–7. doi: 10.1172/JCI118399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Huhtinen HT, Grönroos JO, Grönroos JM, Uksila J, Gelb MH, Nevalainen T, Laine VJ. Antibacterial effects of human group IIA and group XIIA phospholipase A2 against Helicobacter pylori in vitro. APMIS. 2006;114:127–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0463.2006.apm_330.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kumar H, Kawai T, Akira S. Toll-like receptors and innate immunity. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2009;30;388(4):621–5. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.08.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Takeda K, Akira S. Toll-like receptors in innate immunity. Int Immunol. 2005;17:1–14. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxh186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hayashi F, Smith KD, Ozinsky A, Hawn TR, Yi EC, Goodlett DR, Eng JK, Akira S, Underhill DM, Aderem A. The innate immune response to bacterial flagellin is mediated by Toll-like receptor 5. Nature. 2001;410:1099–1103. doi: 10.1038/35074106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hawn TR, Verbon A, Lettinga KD, Zhao LP, Li SS, Laws RJ, Skerrett SJ, Beutler B, Schroeder L, Nachman A, Ozinsky A, Smith KD, Aderem A. A common dominant TLR5 stop codon polymorphism abolishes flagellin signaling and is associated with susceptibility to Legionnaires’ disease. J Exp Med. 2003;198:1563–72. doi: 10.1084/jem.20031220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Del Vecchio A, Laforgia N, Capasso M, Iolascon A, Latini G. The role of molecular genetics in the pathogenesis and diagnosis of neonatal sepsis. Clin Perinatol. 2004;31:53–67. doi: 10.1016/j.clp.2004.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ng P, Li K, Wong RP, Chui K, Wong E, Li G, Fok TF. Proinflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokine responses in preterm infants with systemic infections. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2003;88:F209–13. doi: 10.1136/fn.88.3.F209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Romagnoli C, Frezza S, Cingolani A, De Luca A, Puopolo M, De Carolis MP, Vento G, Antinori A, Tortorolo G. Plasma levels of interleukin-6 and interleukin-10 in preterm neonates evaluated for sepsis. Eur J Pediatr. 2001;160:345–50. doi: 10.1007/pl00008445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schaaf BM, Boehmke F, Esnaashari H, Seitzer U, Kothe H, Maass M, Zabel P, Dalhoff K. Pneumococcal septic shock is associated with the interleukin-10-1082 gene promoter polymorphism. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003;168:476–80. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200210-1164OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stoll BJ, Hansen NI, Higgins RD, Fanaroff AA, Duara S, Goldberg R, Laptook A, Walsh M, Oh W, Hale E. Very low birth weight preterm infants with early onset neonatal sepsis: the predominance of Gram-negative infections continues in the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Neonatal Research Network, 2002–2003. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2005;24:635–9. doi: 10.1097/01.inf.0000168749.82105.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Moore CE, Segal S, Berendt AR, Hill AV, Day NP. Lack of association between Toll-like receptor 2 polymorphisms and susceptibility to severe disease caused by Staphylococcus aureus. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 2004;11:1194–1197. doi: 10.1128/CDLI.11.6.1194-1197.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schultz H, Weiss JP. The bactericidal/permeability-increasing protein (BPI) in infection and inflammatory disease. Clin Chim Acta. 2007;384:12–23. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2007.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nupponen I, Turunen R, Nevalainen T, Peuravuori H, Pohjavuori M, Repo H, Andersson S. Extracellular release of bactericidal/permeability-increasing protein in newborn infants. Pediatr Res. 2002;51:670–4. doi: 10.1203/00006450-200206000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Michalek J, Svetlikova P, Fedora M, Klimovic M, Klapacova L, Bartosova D, Elbl L, Hrstkova H, Hubacek JA. Bactericidal permeability increasing protein gene variants in children with sepsis. Intensive Care Med. 2007;33:2158–64. doi: 10.1007/s00134-007-0860-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]