Abstract

High levels of the critical p53 inhibitor Mdm4 is common in tumors which retain a wild-type p53 allele, suggesting that Mdm4 overexpression is an important mechanism for p53 inactivation during tumorigenesis. To test this hypothesis in vivo, we generated transgenic mice with widespread expression of Mdm4. Two independent lines of transgenic mice, Mdm4Tg1 and Mdm4Tg15 developed spontaneous tumors, the most prevalent of which were sarcomas. To determine whether overexpression of Mdm4 also cooperated with p53 heterozygosity to induce tumorigenesis, we generated Mdm4Tg1 p53+/− mice. These mice had significantly accelerated tumorigenesis and a distinct tumor spectrum with more carcinomas and significantly fewer lymphomas than p53+/− or Mdm4Tg1 mice. Importantly, the remaining wild type p53 allele was retained in most Mdm4Tg1 p53+/− tumors. Mdm4 is thus a bona fide oncogene in vivo, and cooperates with p53 heterozygosity to drive tumorigenesis. These Mdm4 mice will be invaluable for in vivo drug studies of Mdm4 inhibitors.

Introduction

Inactivation of the p53 tumor suppressor is a critical step in tumorigenesis (1). p53 is mutated or deleted in many human cancers. Other tumors with wild-type p53 have defects in critical regulators of p53, such as p14 ARF and Mdm2 (2). Mdm2 inhibits p53 transcriptional activity and mediates the degradation of p53 through its E3 ubiquitin ligase activity (3–5). Amplification of the MDM2 gene occurs in 30–40% of human sarcomas and leukemias many of which retain wild-type p53 (6–8). Also, high levels of MDM2 are found in many other tumors (9, 10), and are associated with poor prognosis in patients with non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (11). In mice, overexpression of Mdm2 induces tumorigenesis in a wild-type p53 background (12). These data demonstrate that Mdm2 is an oncogene in vivo.

Another potential mechanism for disrupting the p53 pathway in tumorigenesis is through Mdm4, an Mdm2 homologue that also inhibits p53 function (13, 14). Mouse embryos lacking Mdm4 die during embryogenesis; however, this phenotype is completely rescued by loss of p53 (14–16). These data demonstrate that Mdm4 is a negative regulator of p53 that is not redundant with Mdm2. Overexpression of Mdm4 with HRasv12 transforms mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) suggesting a role in transformation (17). Additionally, MDM4 is highly expressed in a significant percentage of human tumors including 65% of retinoblastomas (18), 39% of head and neck squamous carcinomas (10), 19% of breast cancers, 19% of colon cancers, 18% of lung cancers (17), and 80% of adult pre-B lymphoblastic leukemia (19). Most retinoblastomas, and head and neck squamous carcinomas have wild type p53 (10, 18). These studies strengthen the argument that MDM4 is an oncogene.

Mdm4 also interacts with Mdm2 through its RING finger (20), which leads to its ubiquitination by Mdm2 and subsequent degradation by the 26S proteasome (21–23). DNA damage induces Mdm4 phosphorylation and subsequent ubiquitination and degradation, which is required for the p53-mediated DNA damage response (24–28). However, the role of Mdm4 overexpression in the p53-mediated DNA damage response in vivo is unclear.

To investigate the effects of Mdm4 overexpression in vivo, we generated transgenic Mdm4 mice using two strategies. Since previous studies show high levels of Mdm2 cause embryonic lethality in mice (12), we reasoned that high levels of Mdm4 might also lead to developmental phenotypes. We therefore created a conditional transgenic mouse (Mdm4Tg ) in which the Mdm4 transgene is expressed only upon deletion of a floxed enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP) cassette (Mdm4Tg1 ). Mdm4Tg1 mice were viable and developed spontaneous tumors. Another transgenic line, Mdm4Tg15, constitutively expressing Mdm4 also showed a cancer phenotype. Lastly, Mdm4Tg1 p53+/− mice showed significantly accelerated tumorigenesis with retention of wild type p53 in most tumors. Mdm4 overexpression also contributed to reduced p53 stability in response to stress. These transgenic Mdm4 mouse models show a direct role of Mdm4 overexpression in tumorigenesis in vivo, and serve as important models for drug screening and cancer therapy.

Material and Methods

Generation of Transgenic Mdm4 Mice

The transgenic Mdm4 mice were generated by pronuclear injection at The University of Texas M. D. Anderson Cancer Center Genetically Engineered Mouse Facility. The transgene was identified by PCR using primers: ALF, AGGGCGGGGTTCGGCTTCTGG and E4re, TCCCAAAAGATCTCCACCACAGTA. To delete EGFP, Mdm4Tg mice were mated with Zp3-Cre mice, and then with C57Bl/6J mice to generate Mdm4Tg1 mice.

Western Blot Analysis

Protein lysates prepared from HeLa and HepG2 cells, MEFs, tissues, and tumors were used for western blots. HeLa and HepG2 cells were originally obtained from ATCC in 2005, and aliquots were subsequently frozen in liquid nitrogen until time of use. The cells were cultured in Eagle's Minimum Essential media supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum as per ATCC recommendations. HeLa and HepG2 cells were authenticated by G-banded karyotyping analysis on 7/7/2010 by MD Anderson Cytogenetics Core Facility. Early passage MEFs generated from 13.5 day post coitum embryos and cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum were used for the analysis. In radiation experiments, 6–8 week-old wild-type and transgenic mice were irradiated at 6 Gy and then sacrificed at different time points. Antibodies used for western blots were: p53 (CM5, Novacastra, MA); p21(BD Biosciences, NJ); cleaved-caspase 3 (Cell Signaling, MA); Mdm4 antibody (MX82); actin, (Santa Cruz biotechnology Inc); vinculin, β-actin, and tubulin (Sigma, MO); Mdm2 (2A10) (Calbiochem, NJ).

Real Time quantitative PCR

Splenocytes were isolated by mashing spleens between the rough part of superfrost slides (Fisher Scientific) and suspended in warm RPMI media (10% Fetal Bovine serum). The cell mixture was then passed through a nylon fiber-filled mini-column (Wako, Japan). The cells were spun down and suspended in 5ml RBC lysis buffer (eBioscience) for 5 minutes. Total RNA was isolated from splenocytes, tissues, and MEFs using Trizol reagent (Invitrogen, CA), and then treated with DNase. cDNAs were made using first strand reverse transcriptase kit (GE Healthcare, UK). The p21, Mdm2, Puma and Gapdh primers were previously described (29). Mdm4 primers for RT-qPCR are: GGAAAAGCCCAGGTTTGACC; and GCCAAATCCAAAAATCCCACT.

LOH of p53 Allele Assay

Tumor DNA was digested with EcoRI and StuI, following a published protocol (30).

Statistical Analysis

Student’s t test and Kaplan-Meier survival analysis were performed using Prism 4 software (GraphPad Software, CA). Differences were considered significant at P<0.05.

Results

Transgenic mice express varying levels of Mdm4

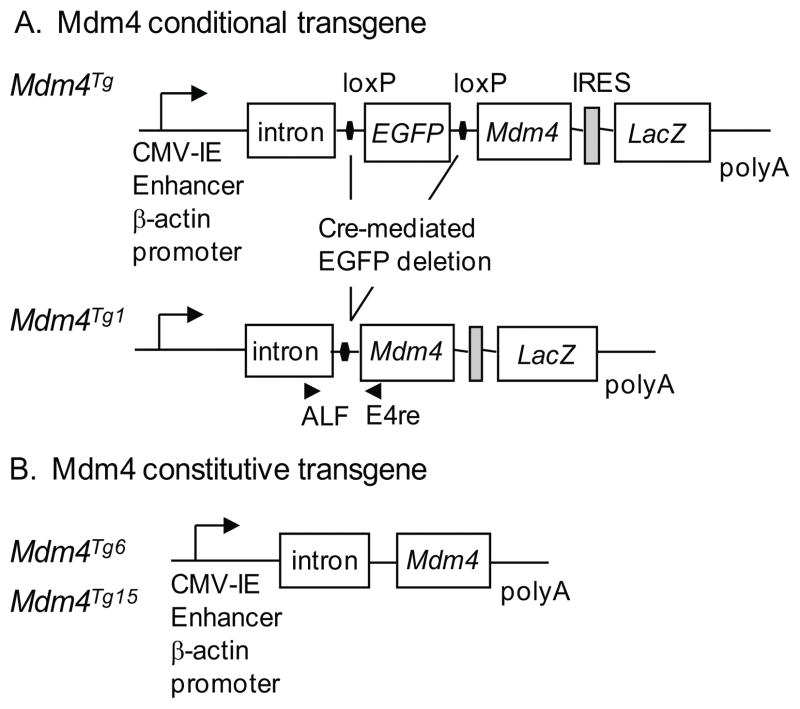

To prevent the potential toxic effects of Mdm4 overexpression on embryonic development, we first generated a conditional mouse model for Mdm4 overexpression. The Mdm4 transgene is driven by the cytomegalovirus (CMV) immediate-early (IE) enhancer, and the chicken β-actin promoter with an intron that drives widespread expression of genes in a number of transgenic models (31). The construct also contained EGFP flanked by loxP sites followed by the Mdm4 cDNA, an internal ribosome entry site (IRES), the lacZ gene and an SV40 polyA sequence (Figure 1). Using this conditional strategy, the entire transgene will be transcribed, and EGFP and lacZ will be translated into protein. Deletion of EGFP allows translation of Mdm4 and lacZ. Transgenic mice were generated and crossed to C57Bl/6J mice. Embryos were screened by whole-mount X-gal staining at embryonic day 13.5. We identified one transgenic line with intense and extensive X-gal staining (referred to as Mdm4Tg) (Supplemental Figure S1A). These mice were subsequently crossed with Zp3-Cre mice (also in a C57Bl/6J background) to delete the EGFP cassette in female germ cells (32), and crossed once again to C57Bl/6J mice to generate Mdm4Tg1 mice that were >87% C57Bl/6J. Detailed analysis of Mdm4Tg1 mice showed positive X-gal staining in the retina on postnatal day 2, and in the heart, kidney, and uterus at 2 months of age (Supplemental Figure S1B and 1C) suggesting that overexpression of the transgene continues throughout the mouse’s life span. In 2 month-old mice, expression of Mdm4 was also determined by real time (RT)-qPCR and western blotting in multiple organs. The heart, muscle, and intestine showed significantly higher expression of Mdm4 than wild type controls (Table 1 and Figure S1D).

Figure 1.

Generation of Mdm4 transgenic mice. (A) The chicken β-actin promoter and intron with a cytomegalovirus (CMV) immediate-early (IE) enhancer drive expression of the Mdm4 cDNA upon deletion of EGFP which is flanked by loxP sites. An internal ribosomal entry site allows LacZ expression. A rabbit β-globin polyadenylation signal (poly A) was placed at the 3’ end. ALF and E4 mark the location of primers for genotyping. (B) A constitutive Mdm4 transgene driven by the chicken β-actin promoter and CMV IE enhancer was used to generate Mdm4Tg6 and Mdm4Tg15 lines.

Table 1.

Mdm4 expression levels*

| Tissues | Mdm4Tg1 | Mdm4Tg6 | Mdm4Tg15 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Spleen | 1.7±1.0 | 2.9±0.6 | 6.7±2.4 |

| Thymus | 1.5±0.4 | 2.6±0.6 | 3.1±1.1 |

| Muscle | 6.5±0.1 | 56.3±12.8 | 23.1±7.4 |

| Liver | 1.1±0.2 | 1.2±0.1 | 8.7±2.9 |

| Intestine | 2.1±0.1 | 8.4±1.7 | 16.8±4.2 |

| Kidney | 0.8±0.1 | 1.2±0.1 | 3.3±0.6 |

| Heart | 6.5±0.1 | 29.6±1.5 | 18.0±4.4 |

| Lung | 0.8±0.1 | 2.1±0.1 | 10.0±2.3 |

The expression levels were compared to tissues from wild type littermates as fold change determined by RT-qPCR

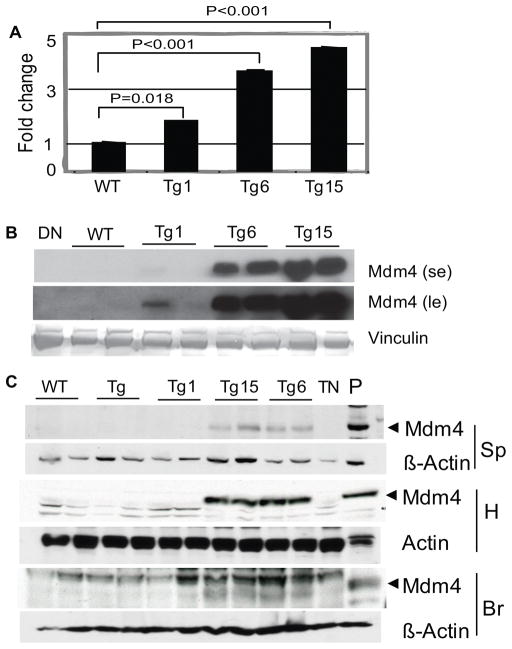

Since Mdm4 transgenic mice did not have obvious developmental defects, we subsequently used a constitutive strategy to drive Mdm4 overexpression (Figure 1B). We obtained two additional transgenic mouse lines, Mdm4Tg6 and Mdm4Tg15. RT-qPCR showed that both lines also had widespread expression of Mdm4 in mouse embryo fibroblasts (MEFs), spleen, thymus, lung, intestine, heart, muscle, liver (Mdm4Tg15 only), and kidney (Mdm4Tg15 only) (Figure 2A and Table 1). Western blot analysis of MEFs, spleen, heart, and brain tissues showed high levels of Mdm4 protein as well (Figure 2B and 2C). Mdm4 protein was not detectable in wild type spleen and heart tissues, and is barely visible in brain (data not shown). In general, expression of Mdm4 was higher in Mdm4Tg6 and Mdm4Tg15 MEFs and tissues than in Mdm4Tg1 samples (Figure 2). Western blots for Mdm2 and p53 were also performed and show undetectable levels of these proteins. All three transgenic lines contain a single copy of the transgene (Supplemental Figure S1E).

Figure 2.

Mdm4 overexpression in mouse tissues of different transgenic lines. (A) Mdm4 mRNA levels in MEFs from Mdm4Tg1, Mdm4Tg6 and Mdm4Tg15 lines were determined by RT-q PCR and plotted as fold change compared to Gapdh with wild type (WT) control set to 1. Three different MEF lines were analyzed for each genotype (p values were calculated by student t-test). (B) Mdm4 protein levels in MEFs from different lines were assayed by western blotting. se, short exposure; le, long exposure.(C) Western blots from various tissues of 2-month-old transgenic Mdm4Tg, Mdm4Tg1, Mdm4Tg6, and Mdm4Tg15 mice using an Mdm4 antibody. β-Actin antibodies were used to determine equal loading of the same blot except for heart (H) as that blot was run longer to eliminate overlap with a non-specific band. Sp, Spleen; Br, Brain; DN, protein lysate from double null (Mdm4−/− p53−/−) cells ; TN, protein lysate from triple null (Mdm2−/− Mdm4−/− p53−/−) cells; P: protein lysate from Mdm4Tg6 MEFs as positive control.

Spontaneous tumorigenesis in Mdm4 transgenic mice

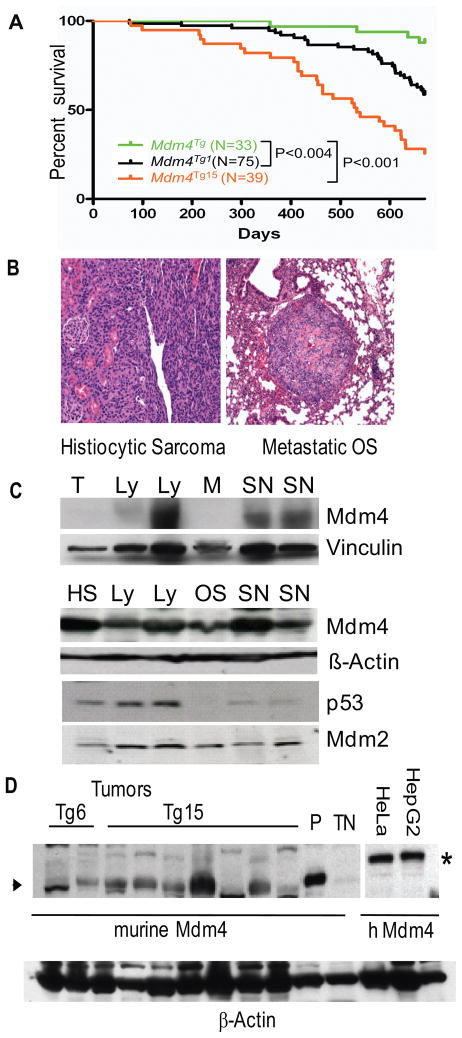

We monitored spontaneous tumorigenesis in Mdm4Tg1 mice, and observed that these mice developed tumors earlier than control Mdm4Tg mice with the EGFP transgene which did not express Mdm4 yet had the same integration site (Figure 3). Mdm4Tg1 mice developed a variety of tumors and died significantly faster than control Mdm4Tg mice (P < 0.004) (Figure 3A). Twenty-six percent of the Mdm4Tg1 mice (20/75) had tumors during the 18-month observation period, and 20% of these had more than one type of tumor. Tumor types observed were sarcomas (38%), lymphomas (33%), histiocytic sarcoma of macrophage origin (17%) (Figure 3B) and carcinomas (13%) (Table 2). One osteosarcoma metastasized to the lung (Table 2; Figure 3B and Supplemental Table 1). Mdm4 levels were higher in tumors as compared to normal tissues; for example, lymphoma vs normal thymus and sarcoma vs normal muscle (Figure 3C and Supplemental Figure 2). Six tumors which were well separated from the surrounding normal tissues had high levels of Mdm4 and Mdm2 by western blot analyses (Figure 3C). p53 was also high in five of six tumors (Figure 3C). The sequences of p53 cDNAs cloned from these six tumors were all wild type for p53. Additional studies of a second transgenic mouse line, Mdm4Tg15 (75% C57Bl/6J), also showed that these mice had shortened life spans and developed spontaneous tumors (P<0.0001 as compared to Mdm4Tg mice). Mdm4Tg15 mice developed 31% histiocytic sarcomas (including 2 metastases), 31% sarcomas (one tumor had metastasis to the spleen), 31% lymphomas, and 7% carcinomas. Four of eleven mice developed more than one type of tumor (Supplemental Table 1). Preliminary data from Mdm4Tg6 mice (3/29) indicated development of lymphomas and adenomas. Mdm4 protein levels were high in 5 of 7 Mdm4Tg15 tumors and both Mdm4Tg6 tumors by western blot analysis (Figure 3D). For comparison, protein lysates from HeLa, and HepG2 human tumor cell lines also showed high levels of Mdm4. These data indicated that overexpression of Mdm4 contributed to a tumor phenotype in mice.

Figure 3.

Spontaneous tumorigenesis in Mdm4Tg1 and Mdm4Tg15 Mice. (A) Kaplan-Meier survival curves for Mdm4Tg, Mdm4Tg1 and Mdm4Tg15 mice. (B) Hematoxylin and eosin staining of spontaneous tumors from Mdm4Tg1 mice: histiocytic sarcoma (20x), and a metastatic osteosarcoma to the lung (10x). (C) Western blots from Mdm4Tg1 tumors and normal tissues using Mdm4, p53, and Mdm2 antibodies. β-actin and vinculin antibodies were used as a control for loading. T, Thymus; M, Muscle; HS, Histiocytic sarcoma; Ly, Lymphoma; OS, Osteosarcoma; SN, Sarcoma, not otherwise specified. (D) Western blot analysis of Mdm4Tg6 and Mdm4Tg15 tumors, HepG2, and HeLa human tumor cell lines for comparison. Asterisk marks human MDM4 and arrowhead marks murine Mdm4 proteins. TN, protein lysate from triple null (Mdm2−/− Mdm4−/− p53−/−) cells; P: protein lysate from Mdm4Tg6 MEFs as positive control.

Table 2.

Tumor Spectra in Mdm4 transgenic mice

| Tumor Types | Mdm4Tg1 (N=24) | p53+/− (N=44) | Mdm4Tg1 p53+/− (N=44) | Mdm4Tg15 (N=13) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sarcoma | 9 (37%) | 30 (68%) | 28 (64%) | 4 (31%) |

| Hemangiosarcoma | 4 | 3 | 1 | 0 |

| Osteosarcoma | 11 | 15 | 18 | 0 |

| Sarcoma, NOS2 | 4 | 12 | 7 | 33 |

| Malignant peripheral Nerve sheath tumor | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Neurofibrosarcoma | 1 | |||

| Carcinoma | 3 (13%) | 2 (5%) | 5 (11%) | 1 (7%) |

| Adenocarcinoma | 2 | 1 | 4 | 0 |

| Spindle Cell Carcinoma | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Squamous Cell Carcinoma | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Hepatocellular Carcinoma | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Lymphoma | 8 (33%) | 10 (23%) | 5 (11%) | 4 (31%) |

| Histiocytic Sarcoma4 | 4 (17%)5 | 2 (5%) | 6 (14%) | 4 (31%)5 |

This Osteosarcoma had metastasis

Not Otherwise Specified

1 of 3 Sarcomas NOS had metastasis

Macrophage origin

2 of 4 Histiocytic Sarcomas had metastasis

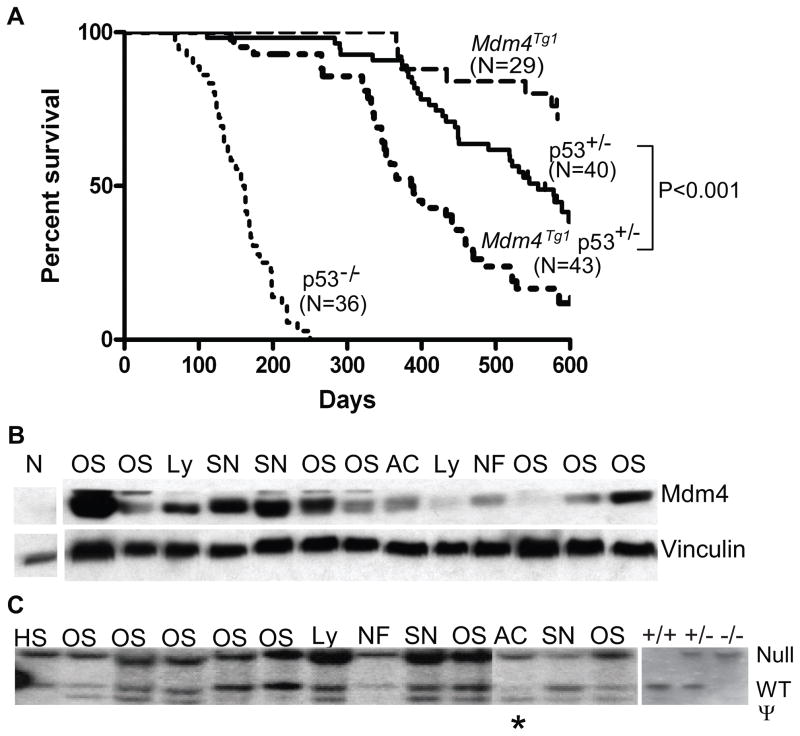

Tumors develop in p53 heterozygous mice at a modest rate resembling human cases of Li-Fraumeni syndrome (30, 33). In approximately half of these tumors, loss of one p53 allele is associated with loss of the second p53 allele. Tumors retaining wild type p53 likely acquire other changes to inactivate the pathway (30, 34). To test the hypothesis that Mdm4 overexpression cooperates with p53 heterozygosity to promote tumorigenesis, we crossed Mdm4Tg1 mice with p53 heterozygous mice (also in a C57Bl/6J background), and monitored spontaneous tumorigenesis. The median survival for the Mdm4Tg1 p53+/− mice was 388 days, which was significantly shorter than Mdm4Tg1 littermates in which <50% of the mice died during 18 months of observation, and p53+/− mice (578 days (P < 0.0001)) (Figure 4A). The Mdm4Tg1 p53+/− mice however lived longer than the p53−/− mice (median survival160 days) (Figure 4A). Additionally, 11% of the tumors (5/44) in Mdm4Tg1 p53+/− mice were carcinomas, which was higher than the percentage of carcinomas in p53+/− littermates (5%). Conversely, the percentage of double-mutant mice with lymphomas (11%) was significantly lower than that of the p53+/− mice (23%; P < 0.02) (Table 2). Interestingly, one Mdm4Tg1 p53+/− mouse had a neurofibrosarcoma, which has not been reported in p53+/− mice (Table 2). Western blot analysis of tumor lysates from Mdm4Tg1 p53+/− indicated that 11 of 13 tumors had high levels of Mdm4 (Figure 4B). We also selected 13 very well isolated tumors including 7 osteosarcomas to perform Southern blot analysis to determine whether these tumors had p53 loss of heterozygosity (LOH). Strikingly, only one of thirteen tumors showed p53 LOH (Figure 4C) compared to p53+/− mice in which approximately half of the tumors show LOH (30, 34). We also sequenced p53 from 7 tumors, 6 of which were wild type for p53. One tumor had a Val to Ala substitution at p53 amino acid 213 which is not one of the known loss-of-function mutations. These data suggest that overexpression of Mdm4 reduced the selective pressure for inactivating the wild type p53 allele in Mdm4Tg1 p53+/− tumors.

Figure 4.

Acceleration of tumorigenesis in p53+/− mice by overexpression of Mdm4. (A) Kaplan-Meier survival curves for Mdm4Tg1, p53+/−, Mdm4Tg1 p53+/−, and p53−/− mice. (B) Western blots of Mdm4Tg1p53+/− tumor lysates using Mdm4 and vinculin antibodies. The first lane is a Mdm4−/− p53−/ − MEF control. (C) Southern blot analysis of Mdm4Tg1 p53+/− tumor DNA samples. The asterisk denotes sample with LOH. HS, Histiocytic sarcoma; OS, osterosarcoma; Ly, lymphoma; NF, Neurofibrosarcoma; SN, Sarcoma, not otherwise specified; AC, Mammary Adenocarcinoma; ψ, p53 pseudogene. p53 homozygous (+/+), heterozygous (+/−) and null (−/−) tail DNAs were used as controls for the southern blot.

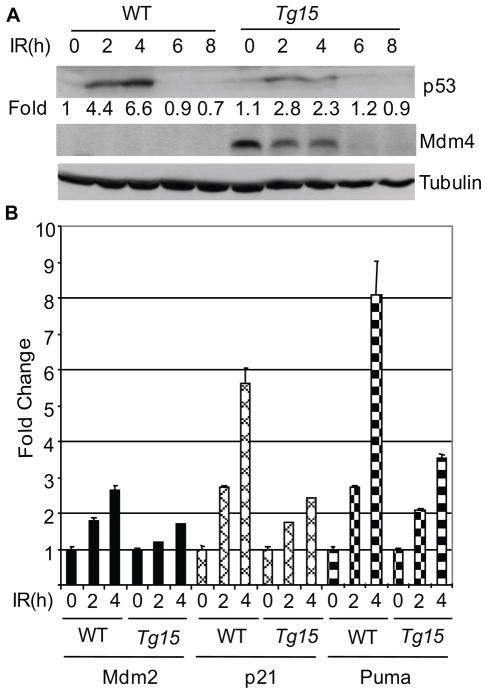

Overexpression of Mdm4 dampened p53 response after IR

The generation of mice with high levels of Mdm4 offered the opportunity to examine the effect on p53 mediated DNA damage response in vivo. To examine the effects of Mdm4 overexpression after DNA damage in vivo, we irradiated Mdm4Tg15 female mice. After IR, Mdm4 protein levels decreased in spleens of Mdm4Tg15 mice consistent with previous in vitro data (23, 28) (Figure 5A). Additionally, p53 was stabilized to a much lower extent in spleen samples of these transgenic mice than in wild-type littermates (Figure 5A and Figure S2). RT-qPCR experiments for activation of p53 downstream target genes showed Mdm2, p21, and Puma mRNA levels (35, 36) were induced to a lesser extend than in wild-type littermates after IR in splenocytes (Figure 5B). These data suggested that Mdm4 transgenic mice exhibit a dampened p53 response after IR.

Figure 5.

Overexpression of Mdm4 suppresses p53 response after ionizing radiation (IR). (A) A time course of p53 and Mdm4 protein levels in spleens of 6 week-old female mice irradiated with 6 Gy. A tubulin antibody was used as control. (B) Activation of p53 transcriptional targets Mdm2, p21, and Puma as measured by RT-qPCR in splenocytes from WT and Mdm4Tg15 mice after 6 Gy IR. Three mice were examined at each time point. h, hours.

Discussion

We generated transgenic mice with widespread expression of Mdm4. All transgenic lines with Mdm4 overexpression were viable and did not show obvious developmental defects. The two transgenic lines Mdm4Tg1 and Mdm4Tg15 examined developed spontaneous tumors (Table 2). This is direct evidence that Mdm4 is a bona fide oncogene that induces tumorigenesis in vivo. While Mdm4Tg1 tumors had high levels of Mdm4, they also had high levels of Mdm2 and p53. High Mdm2 levels are incompatible with p53 stability as Mdm2 is an E3 ubiquitin ligase for p53. Mdm4 cannot degrade p53 but can block Mdm2 access to p53 as they bind the same domain of p53 with similar affinities (37). Notably, Mdm4 overexpression in normal adult tissues in Mdm4Tg1 mice is patchy, but expression of Mdm4 in tumors was high, suggesting tumors arose from Mdm4 overexpressing cells.

The p53-mediated DNA damage response was also dampened in Mdm4 overexpressing cells. After IR treatment, while Mdm4 levels in Mdm4Tg15 mice decreased with time (probably as a cellular response to activate p53), it remained higher than normal at early time points and suppressed transcription of Mdm2, p21, and Puma in splenocytes. Compared to wild type mice, mice overexpressing Mdm4 also showed reduced p53 stabilization after IR. These data are consistent with recently published data that show degradation of Mdm4 after IR is crucial for p53-mediated radiation response (28). High Mdm4 levels may delay the phosphorylation of p53 and therefore hinder p53 stabilization and activation after IR. Since the level of Mdm4 protein affects the radiation response, it may also affect the outcome of radiotherapy in cancer patients.

The median survival of Mdm4Tg1p53+/− mice at 388 days was significantly shorter than that of p53+/− mice at 578 days. Mdm4Tg1p53+/− mice also had significantly decreased lymphoma incidence and increased carcinoma incidence compared to p53+/− mice alone. These data indicate that Mdm4 overexpression not only cooperated with p53 heterozygosity to accelerate tumorigenesis but also altered tumor spectra. More importantly, Mdm4 overexpression in p53+/− mice allowed retention of wild type p53 in most tumors suggesting that overexpression of Mdm4 reduced the selective pressure to inactivate the wild type p53 allele.

Because blocking the inhibitory effects of Mdm4 is a clear therapeutic strategy for cancers with high Mdm4 levels and wild type p53 (38), our Mdm4 transgenic mice will be invaluable for testing the efficacy of Mdm4 inhibitors in vivo. Since human retinoblastomas express high levels of MDM4 and Mdm4Tg1 mice overexpress Mdm4 in the retina, it may be a great model to study the progression of the disease upon inactivation of other members of the Rb pathway (18). Also overexpression of Mdm4 inhibits the therapeutic effect of the Mdm2 inhibitor Nutlin3 (39, 40), indicating that this mouse model can also be useful to examine how overexpression of Mdm4 affects the efficacy of Mdm2 inhibitors.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Parant, and Jackson for helpful discussions. We thank Ana C. Elizondo-Fraire for technical assistance. This work was supported by an institutional research grant and the Center for Targeted Therapy Disease-Specific Grant Program from M. D. Anderson Cancer Center (to SX) and NIH grant CA47296 (to GL).

Abbreviations

- MEFs

mouse embryonic fibroblasts

- IE

Immediate Early

- LOH

Loss of heterozygosity

- IR

ionizing radiation

- Gy

Gray

References

- 1.Vogelstein B, Lane D, Levine AJ. Surfing the p53 network. Nature. 2000;408:307–10. doi: 10.1038/35042675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Attardi LD, Jacks T. The role of p53 in tumour suppression: lessons from mouse models. Cellular & Molecular Life Sciences. 1999;55:48–63. doi: 10.1007/s000180050269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Haupt Y, Maya R, Kazaz A, Oren M. Mdm2 promotes the rapid degradation of p53. Nature. 1997;387:296–9. doi: 10.1038/387296a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Honda R, Tanaka H, Yasuda H. Oncoprotein MDM2 is a ubiquitin ligase E3 for tumor suppressor p53. FEBS Lett. 1997;420:25–7. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(97)01480-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kubbutat MH, Jones SN, Vousden KH. Regulation of p53 stability by Mdm2. Nature. 1997;387:299–303. doi: 10.1038/387299a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Iwakuma T, Lozano G. MDM2, an introduction. Molecular Cancer Research: MCR. 2003;1:993–1000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Watanabe T, Hotta T, Ichikawa A, et al. The MDM2 oncogene overexpression in chronic lymphocytic leukemia and low-grade lymphoma of B-cell origin. Blood. 1994;84:3158–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhou M, Yeager AM, Smith SD, Findley HW. Overexpression of the MDM2 gene by childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia cells expressing the wild-type p53 gene. Blood. 1995;85:1608–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Evans SC, Viswanathan M, Grier JD, Narayana M, El-Naggar AK, Lozano G. An alternatively spliced HDM2 product increases p53 activity by inhibiting HDM2. Oncogene. 2001;20:4041–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Valentin-Vega YA, Barboza JA, Chau GP, El-Naggar AK, Lozano G. High levels of the p53 inhibitor MDM4 in head and neck squamous carcinomas. Hum Pathol. 2007;38:1553–62. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2007.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moller MB, Nielsen O, Pedersen NT. Oncoprotein MDM2 overexpression is associated with poor prognosis in distinct non-Hodgkin's lymphoma entities. Mod Pathol. 1999;12:1010–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jones SN, Hancock AR, Vogel H, Donehower LA, Bradley A. Overexpression of Mdm2 in mice reveals a p53-independent role for Mdm2 in tumorigenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:15608–12. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.26.15608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shvarts A, Steegenga WT, Riteco N, et al. MDMX: a novel p53-binding protein with some functional properties of MDM2. Embo J. 1996;15:5349–57. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Migliorini D, Denchi EL, Danovi D, et al. Mdm4 (Mdmx) regulates p53-induced growth arrest and neuronal cell death during early embryonic mouse development. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:5527–38. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.15.5527-5538.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Parant J, Chavez-Reyes A, Little NA, et al. Rescue of embryonic lethality in Mdm4-null mice by loss of Trp53 suggests a nonoverlapping pathway with MDM2 to regulate p53. Nat Genet. 2001;29:92–5. doi: 10.1038/ng714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Finch RA, Donoviel DB, Potter D, et al. mdmx is a negative regulator of p53 activity in vivo. Cancer Res. 2002;62:3221–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Danovi D, Meulmeester E, Pasini D, et al. Amplification of Mdmx (or Mdm4) directly contributes to tumor formation by inhibiting p53 tumor suppressor activity. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:5835–43. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.13.5835-5843.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Laurie NA, Donovan SL, Shih CS, et al. Inactivation of the p53 pathway in retinoblastoma. Nature. 2006;444:61–6. doi: 10.1038/nature05194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Han X, Garcia-Manero G, McDonnell TJ, et al. HDM4 (HDMX) is widely expressed in adult pre-B acute lymphoblastic leukemia and is a potential therapeutic target. Mod Pathol. 2007;20:54–62. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3800727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Marine JC, Jochemsen AG. Mdmx and Mdm2: brothers in arms? Cell Cycle. 2004;3:900–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pan Y, Chen J. MDM2 promotes ubiquitination and degradation of MDMX. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:5113–21. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.15.5113-5121.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.de Graaf P, Little NA, Ramos YF, Meulmeester E, Letteboer SJ, Jochemsen AG. Hdmx protein stability is regulated by the ubiquitin ligase activity of Mdm2. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:38315–24. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M213034200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kawai H, Wiederschain D, Kitao H, Stuart J, Tsai KK, Yuan ZM. DNA damage-induced MDMX degradation is mediated by MDM2. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:45946–53. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M308295200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen L, Gilkes DM, Pan Y, Lane WS, Chen J. ATM and Chk2-dependent phosphorylation of MDMX contribute to p53 activation after DNA damage. Embo J. 2005;24:3411–22. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pereg Y, Shkedy D, de Graaf P, et al. Phosphorylation of Hdmx mediates its Hdm2- and ATM-dependent degradation in response to DNA damage. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:5056–61. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408595102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Okamoto K, Kashima K, Pereg Y, et al. DNA damage-induced phosphorylation of MdmX at serine 367 activates p53 by targeting MdmX for Mdm2-dependent degradation. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:9608–20. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.21.9608-9620.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jin Y, Dai MS, Lu SZ, et al. 14-3-3gamma binds to MDMX that is phosphorylated by UV-activated Chk1, resulting in p53 activation. Embo J. 2006;25:1207–18. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang YV, Leblanc M, Wade M, Jochemsen AG, Wahl GM. Increased radioresistance and accelerated B cell lymphomas in mice with Mdmx mutations that prevent modifications by DNA-damage-activated kinases. Cancer Cell. 2009;16:33–43. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Xiong S, Van Pelt CS, Elizondo-Fraire AC, Liu G, Lozano G. Synergistic roles of Mdm2 and Mdm4 for p53 inhibition in central nervous system development. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:3226–31. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0508500103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jacks T, Remington L, Williams BO, et al. Tumor spectrum analysis in p53-mutant mice. Current Biology. 1994;4:1–7. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)00002-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Niwa H, Yamamura K, Miyazaki J. Efficient selection for high-expression transfectants with a novel eukaryotic vector. Gene. 1991;108:193–9. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(91)90434-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lewandoski M, Wassarman KM, Martin GR. Zp3-cre, a transgenic mouse line for the activation or inactivation of loxP-flanked target genes specifically in the female germ line. Current Biology. 1997;7:148–51. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(06)00059-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Donehower LA, Godley LA, Aldaz CM, et al. Deficiency of p53 accelerates mammary tumorigenesis in Wnt-1 transgenic mice and promotes chromosomal instability. Genes Dev. 1995;9:882–95. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.7.882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Venkatachalam S, Shi YP, Jones SN, et al. Retention of wild-type p53 in tumors from p53 heterozygous mice: reduction of p53 dosage can promote cancer formation. Embo J. 1998;17:4657–67. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.16.4657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nakano K, Vousden KH. PUMA, a novel proapoptotic gene, is induced by p53. Mol Cell. 2001;7:683–94. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00214-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yu J, Zhang L, Hwang PM, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B. PUMA induces the rapid apoptosis of colorectal cancer cells. Mol Cell. 2001;7:673–82. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00213-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bottger V, Bottger A, Garcia-Echeverria C, et al. Comparative study of the p53- mdm2 and p53-MDMX interfaces. Oncogene. 1999;18:189–99. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wade M, Wahl GM. Targeting Mdm2 and Mdmx in cancer therapy: better living through medicinal chemistry? Mol Cancer Res. 2009;7:1–11. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-08-0423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hu B, Gilkes DM, Farooqi B, Sebti SM, Chen J. MDMX overexpression prevents p53 activation by the MDM2 inhibitor Nutlin. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:33030–5. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C600147200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Patton JT, Mayo LD, Singhi AD, Gudkov AV, Stark GR, Jackson MW. Levels of HdmX expression dictate the sensitivity of normal and transformed cells to Nutlin-3. Cancer Res. 2006;66:3169–76. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-3832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.