Abstract

Previous studies in ovine uterine arteries have demonstrated that sex steroid hormones upregulate ERK1/2 expression and downregulate PKC signaling pathway, resulting in the attenuated myogenic tone in pregnancy. The present study tested the hypothesis that chronic hypoxia during gesttation inhibits the sex steroid-mediated adaptation of ERK1/2 and PKC signaling pathways and increases the myogenic tone of uterine arteries. Uterine arteries were isolated from nonpregnant and near-term pregnant sheep that had been maintained at sea level (~300 m) or exposed to high altitude (3,801 m) hypoxia for 110 days. In contrast to the previous findings in normoxic animals, 17β-estradiol and progesterone failed to suppress PKC-induced contractions and the pressure-induced myogenic tone in uterine arteries from hypoxic animals. Western analyses showed that the sex steroids lost their effects on ERK1/2 expression and phospho-ERK1/2 levels, as well as the activation of PKC isozymes in uterine arteries of hypoxic ewes. In normoxic animals, pregnancy and the sex steroid treatments significantly increased uterine artery estrogen receptor α and progesterone receptor B expression. Chronic hypoxia selectively downregulated estrogen receptor α expression in uterine arteries of pregnant animals, and eliminated the upregulation of estrogen receptor α in pregnancy or by the steroid treatments observed in normoxic animals. The results demonstrate that in the ovine uterine artery chronic hypoxia in pregnancy inhibits the sex steroid hormone-mediated adaptation of decreased myogenic tone by downregulating estrogen receptor α expression, providing a mechanism linking hypoxia and maladaptation of uteroplacental circulation, and an increased risk of preeclampsia in pregnancy.

Keywords: hypoxia, pregnancy, steroids, uterine artery, myogenic tone

Introduction

Pregnancy is associated with a significant decrease in uterine vascular tone and an increase in uterine blood flow to meet the increasing metabolic demands of the mother and developing fetus. Pressure-dependent myogenic contraction is an important physiological mechanism in regulating basal vascular tone and organ blood flow, and decreased pressure-induced myogenic responses of the uterine arteries contribute significantly to the adaptation of uterine vascular hemodynamics in pregnancy.1–5 Recently, we have demonstrated a direct genomic effect of the sex steroid hormones, estrogen and progesterone, in upregulating the extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK1/2) expression and downregulating protein kinase C (PKC) signaling pathway, resulting in the attenuated myogenic tone of uterine arteries in pregnancy.6

Several studies in animal models suggest that a chronic reduction of uteroplacental perfusion leads to the characteristics of preeclampsia found in pregnant women, including hypertension, reduced glomerular filtration rate, proteinuria, intrauterine growth restriction, and endothelial dysfunction.7–9 Chronic hypoxia during gestation is a common stress to maternal cardiovascular homeostasis, and has profound adverse effects on uterine artery contractility, leading to the attenuation of pregnancy-induced increase in uterine blood flow and an increased risk of preeclampsia and fetal intrauterine growth restriction.10–15 Recently, we have demonstrated in sheep that long-term high altitude hypoxia during pregnancy significantly increases the pressure-dependent myogenic tone of resistance-sized uterine arteries by suppressing the ERK1/2 activity and increasing the PKC signaling pathway, leading to the increased Ca2+ sensitivity of myogenic mechanisms.16 The finding that chronic hypoxia eliminated the difference in the pressure-induced myogenic response of the uterine arteries between pregnant and nonpregnant animals16 is intriguing, and suggests that hypoxia inhibits the normal adaptation of uterine vascular myogenic responses during pregnancy. Herein, we present evidence that chronic hypoxia in pregnancy inhibits the sex steroid hormone-mediated adaptation of decreased myogenic tone in the uterine artery by downregulating estrogen receptor α (ERα) expression, providing a mechanism linking hypoxia and maladaptation of uteroplacental circulation, and an increased risk of preeclampsia in pregnancy.

Materials and Methods

An expanded Materials and Methods section is available in the online data supplement at http://hyper.ahajournals.org.

Tissue preparation and treatment

Uterine arteries were isolated from nonpregnant and near-term pregnant (~140 days gestation) sheep maintained at sea-level (altitude: ~300 m; PaO2: 102 ± 2 mmHg) or at high altitude (altitude: 3,801 m; PaO2: 60 ± 2 mmHg) for ~110 days. As described previously,6 arterial preparations were incubated in phenol red-free DMEM with 1% charcoal-stripped FBS for 48 hours at 37 °C in a humidified incubator with 5% CO2/95% air in the absence or presence of 17β-estradiol (E2β), progesterone, ICI 182,780, RU 486, propyl pyrazole triol (PPT), and diarylpropionitrile (DPN), respectively. To investigate the direct effect of hypoxia, some arterial rings obtained from normoxic animals were treated in a humidified incubator with either 21% or 10.5% O2 for 48 hours, as described previosuly.16 All procedures and protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee guidelines.

Measurement of plasma 17β-estradiol

Blood samples were collected from sheep and plasma E2β concentrations were measured by a radioimmunoassay (RIA), as reported previously.17

Measurement of myogenic tone

Pressure-dependent myogenic tone of resistance-sized uterine arteries were measured as described previously.6, 16

Contraction studies

Isometric tensions were measured in tissue baths at 37 °C, as described previously.6, 16

Real-time RT-PCR

mRNA abundance of estrogen receptor α (ERα) and β (ERβ) and progesterone receptor (PR) was determined by real-time RT-PCR, as described previously.18

Western blot analysis

Protein abundance of ERα, ERβ, PR, ERK1/2, and phospho-ERK1/2 was determined with Western blot analysis, as described previously.6, 16

Measurement of PKC isozyme translocation

Protein abundance of PKCα, βI, βII, δ, ε, and ζ in the cytosolic and particulate fractions was determined with Western blot analysis, as described previously.6, 16

Data analysis

Data were expressed as means ± SEM obtained from the number (n) of experimental animals given. Differences were evaluated for statistical significance (P < 0.05) by ANOVA or t-test, where appropriate.

Results

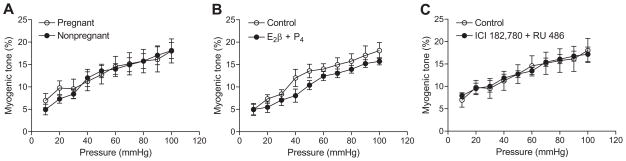

Chronic hypoxia abolishes the steroid hormone-mediated attenuation of pressure-dependent myogenic tone

In contrast to the previous finding in normoxic animals,6 in high altitude hypoxic animals there were no significant differences in the pressure-dependent myogenic tone of uterine arteries between pregnant and nonpregnant sheep (Figure 1A). The E2β (0.3 nmol/L) and progesterone (100.0 nmol/L) treatment for 48 hours did not alter uterine arterial myogenic responses in high altitude nonpregnant sheep (Figure 1B). In accordance, the treatment with the estrogen receptor antagonist ICI 182,780 (10.0 μmol/L) and progesterone receptor antagonist RU 486 (1.0 μmol/L) had no significant effects on myogenic responses of uterine arteries from high altitude pregnant animals (Figure 1C).

Figure 1. Effect of steroid hormones on the pressure-dependent myogenic tone of uterine arteries in high altitude hypoxic sheep.

The myogenic tone of uterine arteries was determined in the presence of 100.0 μmol/L of NG-nitro-L-arginine in nonpregnant and pregnant animals (A), in nonpregnant arteries treated with E2β (0.3 nmol/L) plus progesterone (P4; 100.0 nmol/L) or vehicle control for 48 hours (B), and in pregnant arteries treated with ICI 182,780 (10.0 μmol/L) plus RU 486 (1.0 μmol/L) or vehicle control for 48 hours in the presence of E2β plus P4 (C). Data are mean±SEM of 7 to 9 animals.

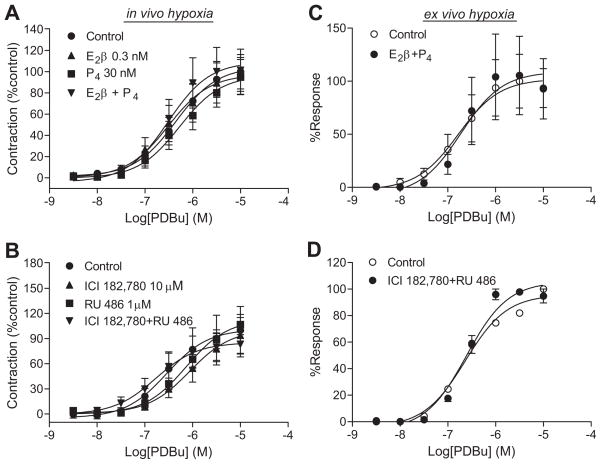

Chronic hypoxia inhibits steroid hormone-regulation of PKC-mediated contractions

In normoxic animals, E2β and progesterone caused a significant decrease in PKC-mediated contractions of the uterine arteries.6 In hypoxic animals, E2β and progesterone treatments had no significant effects on PDBu-induced contractions of the uterine arteries in nonpregnant sheep (Figure 2A). In accordance, ICI 182,780 and RU 486 did not alter the PDBu-induced contractions in pregnant animals (Figure 2B). To determine the direct effect of hypoxia on the inhibition of steroid hormone-regulation of PKC-induced contractions, uterine arteries isolated from low altitude normoxic nonpregnant and pregnant ewes were treated ex vivo with the steroid hormones and their receptor antagonists under either 21% O2 or 10.5% O2 for 48 hours before they were subjected to contraction studies. Similar to the findings in the arteries from high altitude hypoxic animals, the uterine arteries treated with prolonged hypoxia ex vivo lost the responses mediated by the sex steroid hormones (Figure 2C, 2D).

Figure 2. Effect of chronic hypoxia on the steroid hormones-mediated regulation of PDBu-induced contractions.

Uterine arteries were isolated from high altitude hypoxic nonpregnant (A) and pregnant (B) ewes, and from low altitude normoxic nonpregnant (C) and pregnant (D) animals and incubated under 10.5% O2. Nonpregnant arteries were treated with E2β, progesterone (P4), and E2β plus P4 or vehicle control for 48 hours, and pregnant vessels with ICI 182,780 plus RU 486 for 48 hours in the presence of E2β and P4. After the treatments, PDBu-induced contractions were determined. Data are mean±SEM of 7 to 19 high altitude animals, and 8 to 11 low altitude animals.

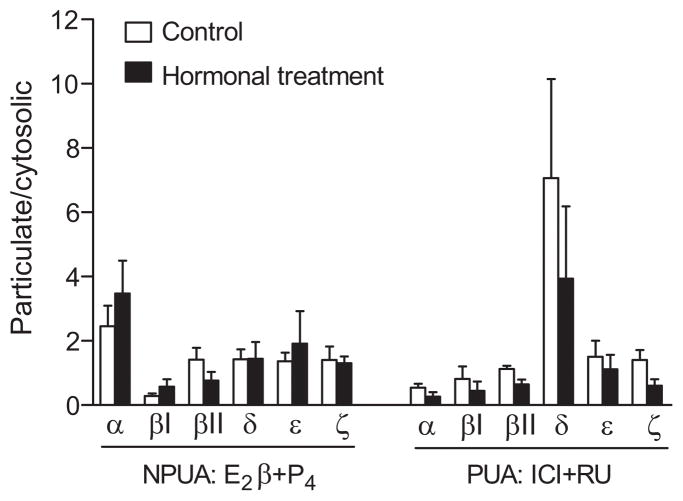

Chronic hypoxia diminishes steroid hormone-mediated PKC isozymes translocation

The sub-cellular distributions of PKC isozymes, α, βI, βII, δ, ε, and ζ, in cytosolic and particulate fractions in the uterine arteries after chronic treatments with E2β and progesterone or their receptor antagonists are shown in Figure 3. In contrast to the previous finding in normoxic animals that E2β and progesterone stimulated the membrane translocation of PKC α, ε, and ζ in the uterine arteries,6 E2β and progesterone failed to cause the membrane translocation in any of the six PKC isozymes in the uterine arteries of high altitude hypoxic nonpregnant sheep (Figure 3). Similarly, the ICI 183,780 and RU 486 treatment had no significant effects on the PKC isozymes translocation in the uterine arteries of hypoxic pregnant animals (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Effect of steroid hormones on PKC activities of uterine arteries in high altitude hypoxic sheep.

Nonpregnant uterine arteries (NPUA) were treated with E2β (0.3 nmol/L) plus progesterone (P4; 100.0 nmol/L) or vehicle control for 48 hours. Pregnant uterine arteries (PUA) were treated with ICI 182,780 (ICI; 10.0 μmol/L) plus RU 486 (RU; 1.0 μmol/L) or vehicle control for 48 hours in the presence of E2β plus P4. PKC isozymes in the cytosolic and particulate fractions were determined by Western blotting and expressed as a ratio of particulate:cytosolic fractions. Data are mean±SEM of 4 to 6 animals. *P<0.05 vs control.

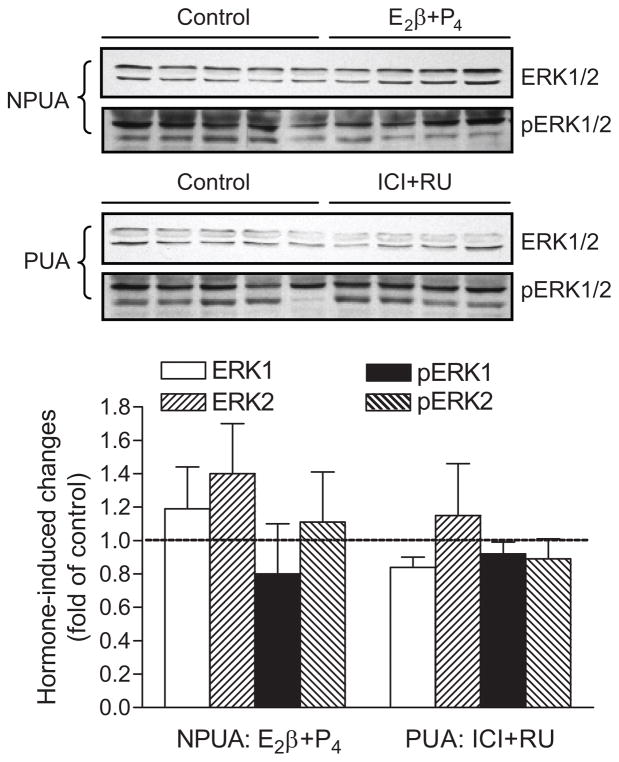

Chronic hypoxia eliminates steroid hormone-upregulation of ERK1/2 expression

As shown in Figure 4, ERK1/2 and phospho-ERK1/2 protein abundance was determined by Western blot analyses in the uterine arteries of high altitude hypoxic ewes. In contrast to the finding in normoxic animals,6 E2β and progesterone treatments had no significant effects on the protein abundance of ERK1/2 and phospho-ERK1/2 in the uterine arteries of hypoxic nonpregnant animals. In accordance, ICI 182,780 and RU 486 did not significantly alter ERK1/2 and phospho-ERK1/2 protein abundance in the uterine arteries of hypoxic pregnant animals.

Figure 4. Effect of steroid hormones on ERK1/2 protein abundance in uterine arteries in high altitude hypoxic sheep.

Nonpregnant uterine arteries (NPUA) were treated with E2β (0.3 nmol/L) plus progesterone (P4; 100.0 nmol/L) or vehicle control for 48 hours. Pregnant uterine arteries (PUA) were treated with ICI 182,780 (ICI; 10.0 μmol/L) plus RU 486 (RU; 1.0 μmol/L) or vehicle control for 48 hours in the presence of E2β plus P4. Protein abundance of total and phosphorylated ERK1/2 was determined by Western blotting. Data are mean±SEM of 5 animals. *P<0.05 vs control.

Chronic hypoxia downregulates ERα expression in uterine arteries

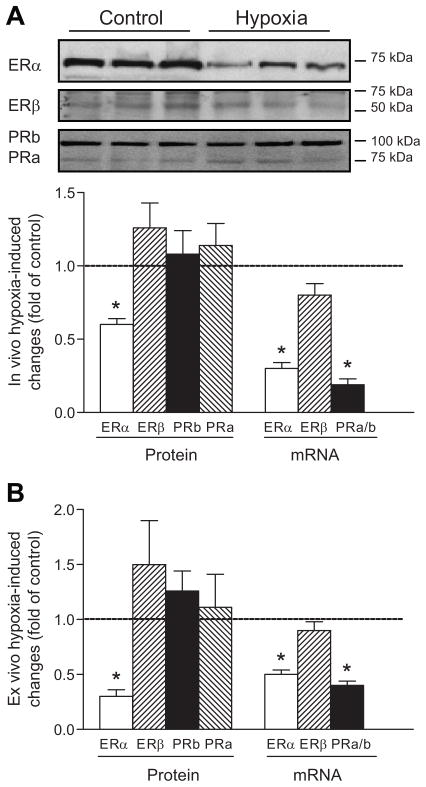

The expression and transcription levels of ERα, ERβ, and progesterone receptors in the vascular smooth muscle of uterine arteries were determined by Western analyses and real-time RT-PCR (Figure 5). In uterine arteries of pregnant animals, the mRNA and protein abundance of combined cytosolic and nuclear ERα, but not ERβ, was significantly decreased in high altitude hypoxic sheep, as compared to low altitude control animals (Figure 5A). In contrast, there was no significant difference in plasma E2β concentrations between low altitude control (81.9 ± 3.5 pg/ml) and high altitude hypoxic (82.3 ± 4.2 pg/ml) pregnant sheep. Interestingly, although progesterone receptor (A/B) mRNA levels were significantly decreased in the hypoxic animals, the protein abundance of progesterone receptor A and B was not significantly different in the uterine arteries between hypoxic and control animals (Figure 5A). To determine the direct effect of hypoxia on the expression of sex hormone receptors, uterine arteries isolated from low altitude normoxic pregnant ewes were treated ex vivo with 21% O2 or 10.5% O2 for 48 hours. Figure 5B shows that the ex vivo hypoxic treatment of uterine arteries produced the results similar to those found in high altitude hypoxic animals (Figure 5A).

Figure 5. Effect of chronic hypoxia on estrogen and progesterone receptor expression in uterine arteries of pregnant ewes.

Estrogen receptor α (ERα) and β (ERβ), progesterone receptor A (PRa) and B (PRb) protein and mRNA abundance was determined by Western blotting and real-time RT-PCR, respectively. A, Uterine arteries were isolated from low altitude normoxic (control) and high altitude hypoxic (hypoxia) pregnant ewes. B, Uterine arteries from low altitude normoxic pregnant ewes were treated under 21% O2 (control) or 10.5% O2 (hypoxia) for 48 hours. Data are mean±SEM of 5 animals. *P<0.05 vs control.

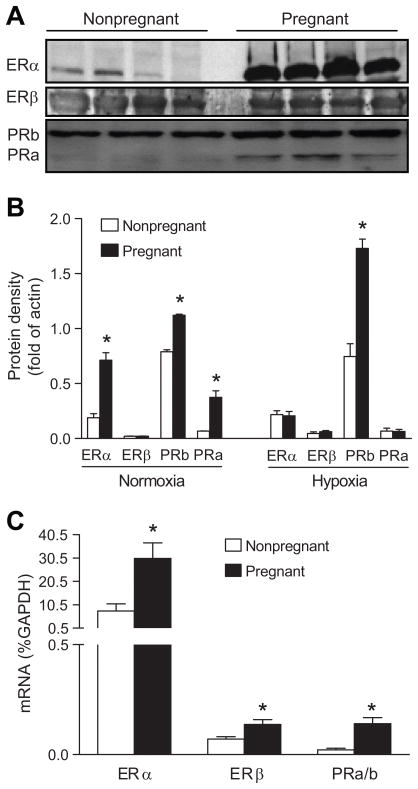

To determine the extent to which chronic hypoxia during gestation inhibits the normal adaptation of sex hormone receptor expression in the uterine artery, protein and mRNA abundance of estrogen and progesterone receptors was measured in uterine arteries of nonpregnant and pregnant sheep in both low altitude and high altitude groups. Western analyses showed that the expression of combined cytosolic and nuclear ERα, as well as progesterone receptors A and B were significantly greater in the uterine arteries of pregnant ewes as compared to that in nonpregnant state in low altitude animals (Figure 6A and 6B). In agreement, the mRNA levels for ERα and progesterone receptors were significantly upregulated in pregnant uterine arteries (Figure 6C). In contrast, there was a dissociation of increased ERβ mRNA levels, but no significant changes in the ERβ protein abundance in the uterine arteries of pregnant, as compared with nonpregnant, animals (Figure 6B and 6C). In the high altitude hypoxic group, pregnant animals demonstrated an increased expression of progesterone receptor B only, but not the others, as compared to their respective nonpregnant groups (Figure 6B).

Figure 6. Effect of pregnancy on estrogen and progesterone receptor expression in uterine arteries in low and high altitude ewes.

Estrogen receptor α (ERα) and β (ERβ), progesterone receptor A (PRa) and B (PRb) protein and mRNA abundance was determined by Western blotting and real-time RT-PCR, respectively. A, Uterine arteries were isolated from pregnant and nonpregnant ewes in low altitude. B, Uterine arteries were isolated from pregnant and nonpregnant ewes in low altitude (normoxia) and high altitude (hypoxia). C, Uterine arteries were isolated from pregnant and nonpregnant ewes in low altitude. Data are mean±SEM of 4 to 5 animals. *P<0.05 vs nonpregnant.

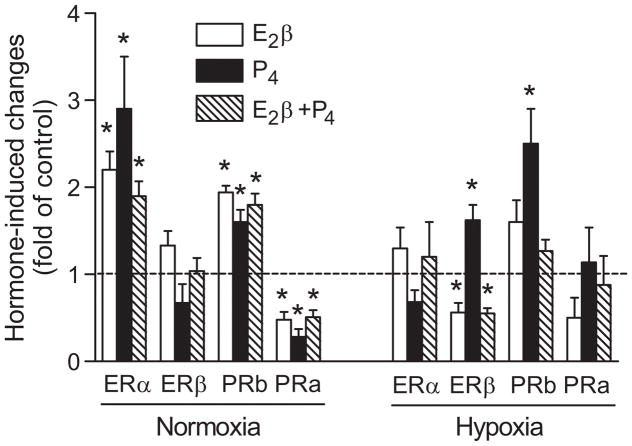

To examine further the role of sex hormones in the regulation of their receptors, uterine arteries isolated from nonpregnant ewes of low altitude and high altitude animals were treated ex vivo with sex steroid hormones under either 21% O2 or 10.5% O2 for 48 hours. In low altitude normoxic animals, the treatment of nonpregnant vessels with E2β, progesterone, and E2β plus progesterone, respectively, demonstrated a greater expression of ERα, progesterone receptor B and a reduced expression of progesterone receptor A, as compared to the untreated groups (Figure 7). In the uterine arteries of high altitude hypoxic animals, the steroid hormone treatments had no significant effects on the abundance of ERα and progesterone receptor A (Figure 7). Whereas E2β decreased ERβ expression, progesterone increased the expression of both ERβ and progesterone receptor B in the uterine arteries in hypoxic animals (Figure 7).

Figure 7. Effect of E2β and progesterone on estrogen and progesterone receptor expression in uterine arteries in low and high altitude ewes.

Uterine arteries were isolated from nonpregnant ewes in low altitude (normoxia) and high altitude (hypoxia) animals, and were treated with E2β (0.3 nmol/L), progesterone (P4; 100.0 nmol/L), and E2β plus P4 or vehicle control for 48 hours. Estrogen receptor α (ERα) and β (ERβ), progesterone receptor A (PRa) and B (PRb) protein and mRNA abundance was determined by Western blotting and real-time RT-PCR, respectively. Data are mean±SEM of 5 animals. *P<0.05 vs control.

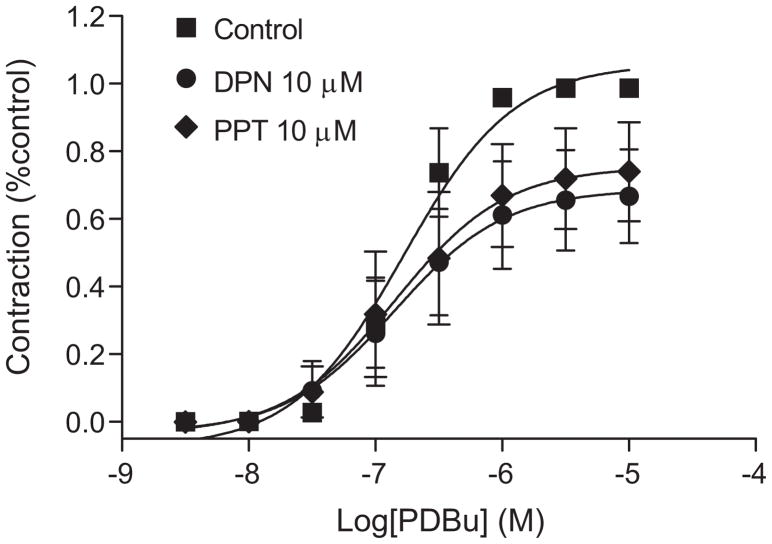

Effect of ERα and ERβ on PKC-mediated contractions

The role of ERα and ERβ in regulating PKC-mediated contractions of the uterine artery was examined in uterine arteries of nonpregnant animals treated ex vivo with selective ERα and ERβ agonists for 48 hours. As shown in Figure 8, the treatment with 10.0μmol/L of the selective ERα agonist, propyl pyrazole triol (PPT) significantly decreased the Emax (75.4 ± 8.9 vs 105.9 ± 5.0% control maximum, P < 0.05) of PDBu-induced contractions. Similarly, 10.0μmol/L of the selective ERβ agonist, diarylpropionitrile (DPN) also significantly reduced the Emax (68.8 ± 8.2 vs 105.9 ± 5.0% control maximum, P < 0.05).

Figure 8. Effect of selective estrogen receptor agonists on PDBu-induced contractions in uterine arteries.

Uterine arteries were isolated from low altitude nonpregnant ewes and were treated with propyl pyrazole triol (PPT; 10.0 μmol/L), diarylpropionitrile (DPN; 10.0 μmol/L) or vehicle control for 48 hours. Data are mean±SEM of 5 animals.

Discussion

The present study demonstrates for the first time that chronic hypoxia diminishes the inhibitory effect of sex steroid hormones on the pressure-dependent myogenic tone of uterine arteries in pregnancy. Estrogen plays a key role in regulating uterine blood flow.19–24 The finding that maternal plasma E2β levels were similar in low and high altitude pregnant ewes is consistent with the previous observations in guinea pigs in which plasma estrogen levels were unaltered by exposure to high altitude, although estrogen-specific responses were diminished in the uterine artery.25 These findings suggest that the hypoxia-mediated effects are imposed on the functional responsiveness of the uterine artery to sex steroid hormones. This is further supported by the present finding that exogenous E2β and progesterone treatments failed to regulate the pressure-dependent myogenic tone of uterine arteries in high altitude ewes.

Previous studies have demonstrated that E2β and progesterone suppress arterial myogenic contractions in women,26 and downregulate myogenic tone of uterine arteries in pregnant sheep.6 The lack of hormone-mediated myogenic responses in hypoxic animals is likely due to the loss of their inhibitory effects on PKC-induced contractions. This is consistent with our previous studies demonstrating that high altitude hypoxia significantly increased PKC-induced contractions in pregnant ewes, and abolished the differences in PKC-mediated uterine arterial contractions between nonpregnant and pregnant animals.16 PKC plays an important role in regulating pressure-dependent myogenic responses of resistance arteries,1, 27, 28 and a decrease in the PKC signaling pathway accounts for attenuated myogenic tone of the uterine artery in pregnancy.1, 29–34 In low altitude normoxic sheep, the genomic action of the sex hormones in attenuating the myogenic tone of uterine arteries is mediated by the down-regulation of the PKC signaling pathway in the vascular smooth muscle.6 Similar findings have been obtained in monkeys, showing that physiological concentrations of estrogen and progesterone have inherent effects in vascular smooth muscle cells, and that they suppress PKC activity and myogenic contractions of the coronary artery.35, 36 In contrast to the findings in the normoxic animals that E2β and progesterone significantly reduced the basal activity of PKCα, ε, and ζ in the uterine artery,6 the hormones had no significant effects on the activities of PKC isozymes determined in the hypoxic animals. In a previous study, we demonstrated that chronic hypoxia significantly increased the activity of PKCε in pregnant uterine arteries, and abolished the difference in the PKCε activity in the uterine arteries between nonpregnant and pregnant sheep.16 These findings suggest that chronic hypoxia during pregnancy inhibits the sex hormones-mediated downregulation of PKCε activity, resulting in increased PKC-mediated contractions and myogenic responses in uterine arteries.

The finding that E2β and progesterone had no effects on protein levels of total and phosphorylated ERK1/2 in the uterine arteries from high altitude hypoxic animals is intriguing, and suggests a possible upstream mechanism for the lost responses of PKC-induced contractions and myogenic tone to the sex hormones in the hypoxic animals. The previous studies have demonstrated that hormone-mediated increases in ERK1/2 gene expression act as an upstream signal in suppressing PKC-mediated contractions and myogenic tone of uterine arteries in pregnant animals.1, 6, 29 In addition to the genomic function in the nucleus, estrogens activate multiple signal transduction cascades, including ERK, in the extra-nuclear compartment, possibly through protein methylation of ERα.37 Unlike breast cancer cells in which increased ERK activity represses ERα, both ERα and ERK are upregulated and activated in the uterine artery of pregnant animals.6 The potential effect of ERK on ERα expression in the uterine artery remains to be determined. The finding that inhibition of ERK1/2 restored the sex hormone-mediated attenuation of PKC-induced contractions in uterine arteries,6 indicates a key role of ERK1/2 activation in the hormone-induced suppression of PKC activity and myogenic responses. Consistent with the present finding, the previous study demonstrated that high altitude hypoxia resulted in a significant decrease in ERK1/2 protein expression in uterine arteries of pregnant sheep, and abolished the difference in ERK1/2 levels between pregnant and nonpregnant ewes, as demonstrated in low altitude animals.16 This lack of the hormonal upregulation of ERK1/2 in uterine arteries of pregnant ewes in high altitude hypoxic animals is likely to result in the increased PKCε activity and PDBu-induced contractions in uterine arteries in the hypoxic animals, as demonstrated previously.16

The question arises as to the mechanism by which chronic hypoxia during gestation might alter the sex hormone-mediated responses in uterine arteries. Consistent with the previous study,38 the present study demonstrated that ERα was the dominant receptor in the uterine artery. In contrast to the previous finding that ERβ but not ERα was increased in the vascular smooth muscle of uterine arteries in pregnant sheep,38 the present study demonstrated a greater abundance of ERα and ERβ mRNA and ERα protein in the uterine artery in pregnant animals. This may be because the cytosolic receptors were mainly determined in the previous study,38 whereas in the present study the combined cytosolic and nuclear hormonal receptors were measured. Although the conditions of ovarian cycle of luteal or follicular phases were not determined in nonpregnant animals in the present study, pregnancy is a stage of high steroid hormone concentrations. The potential effect of the ovarian cycle on the steroid hormone receptors needs to be further investigated. The physiological importance of a greater ERα expression in pregnancy has been demonstrated in human uterine arteries. This leads to a lower collagen concentration resulting in reduced tissue stiffness and increased distensibility of the uterine artery to accommodate the marked elevation in uterine blood flow.39 Similar findings were obtained in sheep showing a correlation of higher ERα levels (the present study) and the increased distensibility1 of the uterine artery in pregnant animals.

To our knowledge, the effect of pregnancy on progesterone receptors in the uterine artery has not been studied previously. The increased expression of progesterone receptor A and B in the uterine artery smooth muscle in pregnant animals is consistent with the role of progesterone in downregulating myogenic contractions of the uterine arteries in pregnancy.6 In several other tissues including the endometrium, progesterone may antagonize the actions of estrogen, but this does not occur in uterine arteries. Although the effect of progesterone in regulating uterine blood flow is less clear, and appears controversial in animal studies between the ovarian cycle and the pregnancy, it has been demonstrated that in the second half of pregnancy and at term, increases in uterine blood flow directly relate with progesterone concentrations and even more prominently with the sum of progesterone and estrogen.40, 41

Of interest, the present study demonstrates that high altitude hypoxic exposure during pregnancy suppresses ERα expression in the uterine artery, providing a mechanism for the hypoxia-induced inhibition of sex hormone-mediated responses in uterine arteries. Consistent with this finding, the diameter of uterine arteries and uterine blood flow were found to be significantly reduced in pregnant women residing at high altitude.14 This is most likely due to the direct effect of chronic hypoxia, given that the ex vivo prolonged hypoxic treatment of isolated uterine arteries from the normoxic ewes produced the similar effects on ERα expression as that found in uterine arteries in high altitude hypoxic animals. This is consistent with the finding that chronic hypoxia had a direct effect on increased PKC-induced contractions and myogenic responses of the uterine artery in pregnant ewes.16 The direct effects of steroid hormones in regulating the hormonal receptors in the vascular smooth muscle of uterine arteries demonstrated in the present study are consistent with the premise that ovarian steroids maintain and regulate expression of their own receptors, and are largely in agreement with the previous findings of the effect of in vivo hormonal treatments on steroid receptor expression in uterine arteries in sheep.38 Of interest, in high altitude hypoxic animals the hormonal-mediated upregulation of ERα expression was abolished, leading to no significant difference in the ERα density in uterine arteries between nonpregnant and pregnant animals. The mechanism(s) for the hypoxia-mediated loss of hormonal effects on the up-regulation of ERα expression in uterine arteries are not clear at present. Given the findings that chronic hypoxia increases global DNA methylation levels,42 and that ERα gene promoter contains CpG islands,43–45 it is plausible to speculate that increased promoter methylation may contribute to ERα gene repression in the uterine artery in response to chronic hypoxia. Indeed, it has been shown that hypermethylation of promoter CpG islands is associated with the loss of ERα expression and function.46–49 The finding that hypoxia decreased progesterone receptor mRNA but not protein abundance is intriguing, and suggests a compensatory upregulation of translation, supporting an essential role of progesterone receptors in maintaining the pregnancy.

It has been demonstrated that E2β confers its vascular protective effect primarily via ERα rather than ERβ.50, 51 However, it is unknown if ERα or ERβ, or both mediate the estrogen-induced downregulation of uterine artery myogenic responses and rise in uterine blood flow. The present study provides the first evidence that activation of either ERα or ERβ suppresses PKC-induced contractions and hence myogenic responses of uterine arteries. The two selective agonists, propyl priol triol and diproprionitrile have been widely used in studying the effects of ERα and ERβ. The present finding is somewhat different to the other studies showing that ERα, but not ERβ, is implicated in the regulation of myogenic responses in subcutaneous and mesenteric arteries.52, 53 However, the differences in the expression and function of estrogen receptors between uterine arteries and other systemic vessels have been well demonstrated.38 Given that both ERα and ERβ agonists suppress PKC-mediated contractions while only ERα but not ERβ is downregulated by chronic hypoxia, it is possible for ERβ to play a parallel or compensatory role to suppress the myogenic tone.

PERSPECTIVES

The present study demonstrates that chronic hypoxia inhibits the steroid hormone-mediated adaptation of ERK1/2 and PKC signaling pathways to cause an increase in the myogenic tone of uterine arteries in pregnancy. Although it may be difficult to translate the present findings directly to humans, the possibility that the hypoxia-mediated dysregulation of myogenic tone contributes to the maladaptation of uteroplacental circulation with a consequence of increased pregnancy complications provides a mechanistic understanding worthy of investigation in humans. This is because hypoxia during gestation is a common stress to maternal cardiovascular homeostasis, causing a reduction of uteroplacental perfusion and an increased risk of preeclampsia. Given that ERα is the predominant receptor in the estrogen-mediated protective effect of vascular remodeling, the novel finding of the hypoxia-induced down-regulation of ERα expression in the vascular smooth muscle is likely to have broader implications in addition to the regulation of vascular contractility. In addition, the potential epigenetic mechanism of DNA methylation in the hypoxia-mediated ERα gene repression in the vascular smooth muscle presents an intriguing area for the future investigation.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Sources of Funding: This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants HD31226 (L.D.L and L.Z.), HL89012 (L.Z.), HL83966 (L.Z.), and DA025319 (S.Y.).

Footnotes

Disclosures:

None.

References

- 1.Xiao D, Buchholz JN, Zhang L. Pregnancy attenuates uterine artery pressure-dependent vascular tone: role of PKC/ERK pathway. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2006;290:H2337–H2343. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01238.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grandley RE, Conrad KP, McLaughlin MK. Endothelin and nitric oxide mediate reduced myogenic reactivity of small renal arteries from pregnant rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2001;280:R1–R7. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.2001.280.1.R1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Veerareddy S, Cooke CL, Baker PN, Davidge ST. Vascular adaptations to pregnancy in mice: effects on myogenic tone. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2002;283:H2226–H2233. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00593.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kublickiene KR, Cockell AP, Nisell H, Poston L. Role of nitric oxide in the regulation of vascular tone in pressurized and perfused resistance myometrial arteries from term pregnant women. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1997;177:1263–1269. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(97)70048-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kublickiene KR, Kublickas M, Lindblom B, Lunell NO, Nisell H. A comparison of myogenic and endothelial properties of myometerial and omental resistance vessels in late pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1997;176:560–566. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(97)70548-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Xiao D, Huang X, Yang S, Zhang L. Direct Chronic Effect of Steroid Hormones in Attenuating Uterine Arterial Myogenic Tone. Role of Protein Kinase C/Extracellular Signal–Regulated Kinase 1/2. Hypertension. 2009;54:352–358. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.109.130781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Crew JK, Herrington JN, Granger JP, Khalil RA. Decreased endothelium-dependent vascular relaxation during reduction of uterine perfusion pressure in pregnant rat. Hypertension. 2000;35:367–372. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.35.1.367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Khalil RA, Granger JP. Vascular mechanisms of increased arterial pressure in preeclampsia: lessons from animal models. Am J Physiol Regulatory Integrative Comp Physiol. 2002;283:29–45. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00762.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Walsh SK, English FA, Johns EJ, Kenny LC. Plasma-mediated vascular dysfunction in the reduced uterine perfusion pressure model of preeclampsia: A microvascular characterization. Hypertension. 2009;54:345–351. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.109.132191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Julian CG, Galan HL, Wilson MJ, Desilva W, Cioffi-Ragan D, Schwartz J, Moore LG. Lower uterine artery blood flow and higher endothelin relative to nitric oxide metabolite levels are associated with reductions in birth weight at high altitude. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2008;295:R906–R915. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00164.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Keyes LE, Armaza JF, Niermeyer S, Vargas E, Young DA, Moore LG. Intrauterine growth restriction, preeclampsia, and intrauterine mortality at high altitude in Bolivia. Pediatr Res. 2003;54:20–25. doi: 10.1203/01.PDR.0000069846.64389.DC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Palmer SK, Moore LG, Young D, Cregger B, Berman JC, Zamudio S. Altered blood pressure course during normal pregnancy and increased preeclampsia at high altitude (3100 meters) in Colorado. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1999;180:1161–1168. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(99)70611-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.White M, Zhang L. Effects of chronic hypoxia on maternal vascular changes during pregnancy. High Alt Med Biol. 2003;4:157–169. doi: 10.1089/152702903322022776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zamudio S, Palmer SK, Droma T, Stamm E, Coffin C, Moore LG. Effect of altitude on uterine artery blood flow during normal pregnancy. J Appl Physiol. 1995;79:7–14. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1995.79.1.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zamudio S, Palmer SK, Dahms TE, Berman JC, Young DA, Moore LG. Alterations in uteroplacental blood flow precede hypertension in preeclampsia at high altitude. J Appl Physiol. 1995;79:15–22. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1995.79.1.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chang K, Xiao D, Huang X, Longo LD, Zhang L. Chronic hypoxia increases pressure-dependent myogenic tone of the uterine artery in pregnant sheep: role of ERK/PKC pathway. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2009;296:H1840–H1849. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00090.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Geng C, Mao C, Wu L, Cheng Y, Liu R, Chen B, Chen L, Xu Z. Cholinergic signal activated renin angiotensin system associated with cardiovascular changes in the ovine fetus. J Perinat Med. 2010;38:71–76. doi: 10.1515/JPM.2010.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Meyer K, Zhang H, Zhang L. Direct effect of cocaine on epigenetic regulation of PKCε gene repression in the fetal rat heart. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2009;47:504–511. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2009.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Magness RR, Rosenfeld CR. Local and systemic estradiol-17 beta: effects on uterine and systemic vasodilation. Am J Physiol. 1989;256:E536–E542. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1989.256.4.E536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Magness RR, Parker CR, Jr, Rosenfeld CR. Systemic and uterine responses to chronic infusion of estradiol-17 beta. Am J Physiol. 1993;265:E690–E698. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1993.265.5.E690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Magness RR, Phernetton TM, Gibson TC, Chen DB. Uterine blood flow responses to ICI 182 780 in ovariectomized oestradiol-17beta-treated, intact follicular and pregnant sheep. J Physiol. 2005;565:71–83. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.086439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gibson TC, Phernetton TM, Wiltbank MC, Magness RR. Development and use of an ovarian synchronization model to study the effects of endogenous estrogen and nitric oxide on uterine blood flow during ovarian cycles in sheep. Biol Reprod. 2004;70:1886–1894. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.103.019901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ford SP, Christenson RK. Blood flow to uteri of sows during the estrous cycle and early pregnancy: local effect of the conceptus on the uterine blood supply. Biol Reprod. 1979;21:617–624. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod21.3.617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ford SP, Reynolds LP, Magness RR. Blood flow to the uterine and ovarian vascular beds of gilts during the estrous cycle or early pregnancy. Biol Reprod. 1982;27:878–885. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod27.4.878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rockwell LC, Keyes LE, Moore LG. Chronic Hypoxia Diminishes Pregnancy-associated DNA Synthesis in Guinea Pig Uteroplacental Arteries. Placenta. 2000;21:313–319. doi: 10.1053/plac.1999.0487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kublickiene K, Fu XD, Svedas E, Landgren BM, Genazzani AR, Simoncini T. Effects in postmenopausal women of estradiol and medroxyprogesterone alone and combined on resistance artery function and endothelial morphology and movement. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93:1874–1883. doi: 10.1210/jc.2007-2651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Davis MJ, Hill MA. Signaling mechanisms underlying the vascular myogenic response. Physiol Rev. 1999;79:387–423. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1999.79.2.387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Osol G, Laher I, Cipolla M. Protein kinase C modulates basal myogenic tone in resistance arteries from the cerebral circulation. Circ Res. 1991;68:359–367. doi: 10.1161/01.res.68.2.359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Xiao D, Zhang L. ERK MAP kinases regulate smooth muscle contraction in ovine uterine artery: effect of pregnancy. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2002;282:H292–H300. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2002.282.1.H292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Xiao D, Zhang L. Adaptation of uterine artery thick- and thin- filament regulatory pathway to pregnancy. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2005;288:H142–H148. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00655.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kanashiro CA, Cockrell KL, Alexander BT, Granger JP, Khalil RA. Pregnancy-associated reduction in vascular protein kinase C activity rebounds during inhibition of NO synthesis. Am J Physiol. 2000;278:R295–R303. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.2000.278.2.R295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Magness RR, Rosenfeld CR, Carr BR. Protein kinase C in uterine and systemic arteries during ovarian cycle and pregnancy. Am J Physiol. 1991;260:E464–E470. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1991.260.3.E464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Farley DB, Ford SP. Evidence for declining extracellular calcium uptake and protein kinase C activity in uterine arterial smooth muscle during gestation in gilts. Biol Reprod. 1992;46:315–321. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod46.3.315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ford SP. Control of blood flow to the gravid uterus of domestic livestock species. J Anim Sci. 1995;73:1852–1860. doi: 10.2527/1995.7361852x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Miyagawa K, Rosch J, Stanczyk F, Hermsmeyer K. Medroxyprogesterone interferes with ovarian steroid protection against coronary vasospasm. Nat Med. 1997;3:324–327. doi: 10.1038/nm0397-324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Minshall RD, Miyagawa K, Chadwick CC, Novy MJ, Hermsmeyer K. In vitro modulation of primate coronary vascular muscle cell reactivity by ovarian steroid hormones. FASEB J. 1998;12:1419–1429. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.12.13.1419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Le Romancer M, Treilleux I, Bouchekioua-Bouzaghou K, Sentis S, Corbo L. Methylation, a key step for nongenomic estrogen signaling in breast tumors. Steroids. 2010;75:560–564. doi: 10.1016/j.steroids.2010.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Byers MJ, Zangl A, Phernetton TM, Lopez G, Chen DB, Magness RR. Endothelial vasodilator production by ovine uterine and systemic arteries: ovarian steroid and pregnancy control of ER-alpha and ER-beta levels. J Physiol. 2005;565:85–99. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.085753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lydrup ML, Ferno M. Correlation between estrogen receptor α expression, collagen content and stiffness in human uterine arteries. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2003;82:610–615. doi: 10.1080/j.1600-0412.2003.00209.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Caton D, Kalra PS. Endogenous hormones and regulation of uterine blood flow during pregnancy. Am J Physiol. 1986;250:R365–R369. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1986.250.3.R365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ford SP, Reynolds LP, Farley DB, Bhatnagar RK, Van Orden DE. Interaction of ovarian steroids and periarterial alpha 1-adrenergic receptors in altering uterine blood flow during the estrous cycle of gilts. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1984;150:480–484. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(84)90424-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Watson JA, Watson CJ, McCrohan AM, Woodfine K, Tosetto M, McDald J, Gallagher E, Betts D, Baugh J, O'Sullivan J, Murrell A, Watson RW, McCann A. Generation of an epigenetic signature by chronic hypoxia in prostate cells. Hum Mol Genet. 2009;18:3594–3604. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddp307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kastner P, Krust A, Turcotte B, Stropp U, Tora L, Gronemeyer H, Chambon P. Two distinct estrogen-regulated promoters generate transcripts encoding the two functionally different human progesterone receptors forms A and B. EMBO J. 1990;9:1603–1614. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1990.tb08280.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sasaki M, Kaneuchi M, Fujimoto S, Tanaka Y, Dahiya R. Hypermethylation can selectively silence multiple promoters of steroid receptors in cancers. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2003;202:201–207. doi: 10.1016/s0303-7207(03)00084-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yang H, Chen CM, Yan P, Huang THM, Shi H, Burger M, Nimmrich I, Maier S, Berlin K, Caldwell CW. The androgen receptor gene is preferentially hypermethylated in follicular non-Hodgkin's lymphomas. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9:4034–4042. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ottaviano YL, Issa JP, Parl FF. Methylation of the estrogen receptor gene CpG island marks loss of estrogen receptor expression in human breast cancer cells. Cancer Res. 1994;54:2552–2555. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Iwase H, Omoto Y, Iwata H. DNA methylation analysis at distal and proximal promoter regions of the oestrogen receptor gene in breast cancers. Br J Cancer. 1999;80:1982–1986. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6690631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lau KM, LaSpina M, Long J, Ho SM. Expression of estrogen receptor ER alpha and ER beta in normal and malignant prostatic epithelial cells: Regulation by methylation and involvement in growth regulation. Cancer Res. 2000;60:3175–3182. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nojima D, Li LC, Dharia A. CpG hypermethylation of the promoter region inactivates the estrogen receptor-beta gene in patients with prostate carcinoma. Cancer. 2001;92:2076–2083. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20011015)92:8<2076::aid-cncr1548>3.0.co;2-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pare G, Krust A, Karas RH, Dupont S, Aronovitz M, Chambon P, Mendelsohn ME. Estrogen receptor-alpha mediates the protective effects of estrogen against vascular injury. Circ Res. 2002;90:1087–1092. doi: 10.1161/01.res.0000021114.92282.fa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Karas RH, Schulten H, Pare G, Aronovitz MJ, Ohlsson C, Gustafsson JA, Mendelsohn ME. Effects of estrogen on the vascular injury response in estrogen receptor alpha, beta (double) knockout mice. Circ Res. 2001;89:534–539. doi: 10.1161/hh1801.097239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kublickiene K, Svedas E, Landgren BM, Crisby M, Nahar N, Nisell H, Poston L. Small artery endothelial dysfunction in postmenopausal women: in vitro function, morphology, and modification by estrogen and selective estrogen receptor modulators. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90:6113–6122. doi: 10.1210/jc.2005-0419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Douglas G, Cruz MN, Poston L, Gustafsson JA, Kublickiene K. Functional characterization and sex differences in small mesenteric arteries of the estrogen receptor-beta knockout mouse. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2008;294:R112–R120. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00421.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.