Abstract

Thermally responsive elastin-like polypeptides (ELPs) are a promising class of recombinant biopolymers for the delivery of drugs and imaging agents to solid tumors via systemic or local administration. This article reviews four applications of ELPs to drug delivery, with each delivery mechanism designed to best exploit the relationship between the characteristic transition temperature (Tt) of the ELP and body temperature (Tb). First, when Tt >> Tb, small hydrophobic drugs can be conjugated to the C-terminus of the ELP to impart the amphiphilicity needed to mediate the self-assembly of nanoparticles. These systemically delivered ELP-drug nanoparticles preferentially localize to the tumor site via the EPR effect, resulting in reduced toxicity and enhanced treatment efficacy. The remaining three approaches take direct advantage of the thermal responsiveness of ELPs. In the second strategy, where Tb < Tt < 42 °C, an ELP-drug conjugate can be injected in conjunction with external application of mild hyperthermia to the tumor to induce ELP coacervation and an increase in concentration within the tumor vasculature. The third approach utilizes hydrophilic-hydrophobic ELP block copolymers that have been designed to assemble into nanoparticles in response to hyperthermai due to the independent thermal transition of the hydrophobic block, thus resulting in multivalent ligand display of a ligand for spatially enhanced vascular targeting. In the final strategy, ELPs with Tt < Tb are conjugated with radiotherapeutics, injtect intioa tumor where they undergo coacervation to form an injectable drug depot for intratumoral delivery. These injectable coacervate ELP-radionuclide depots display a long residence in the tumor and result in inhibition of tumor growth.

Keywords: elastin-like polypeptide, biopolymer, hyperthermia, thermally responsive polymer, pH-controlled release, lower critical solution temperature, cancer therapy, micelles

1. Introduction

One of the primary goals of drug delivery for cancer therapy is to improve the therapeutic index of anticancer drugs by increasing the amount of drug delivered to the tumor site and decreasing its exposure to healthy tissues; the therapeutic index is defined as the ratio of LD50 to ED50, where the median lethal dose (LD50) is defined as the dose necessary to cause death in 50% of a population, and the minimum effective dose (ED50) is defined as the smallest dose able to induce the desired effect in 50% of a population. A large therapeutic index is preferable as it describes a situation in which the efficacious dose is far below the lethal dose. Unfortunately, many cancer chemotherapeutics are hydrophobic compounds with a MW of less than 500 Da that have suboptimal pharmacokinetics, significant systemic toxicity and a small therapeutic index. This low therapeutic index has two main causes: first, upon injection into the systemic blood circulation, only a small fraction of these low MW compounds accumulate in the body, while the bulk of the drug is rapidly cleared through the kidneys. Second, because the cellular toxicity of these molecules is correlated with drug concentration and length of exposure, both healthy cells and tumor tissue are subjected to the same distribution profile, resulting in similar toxicities. Although increasing the injected dose increases the amount of drug that reaches the tumor site, it also exacerbates undesirable side effects, whereas reducing the dose to minimize side effects makes the drug less effective. Furthermore, because many of these drugs are hydrophobic they are poorly soluble in water, which also limits the maximum solubility of the drug and hence the amount of therapeutically active drug able to reach the desired site of action.

Engineered drug carriers provide a means to improve the therapeutic index of anticancer drugs through conjugation of the drug to macromolecular carriers such as polymers [1, 2], proteins [3], and polysaccharides [4], or by encapsulation within liposomes [5], polymer micelles [6], and nanoscale polymer emulsions [7]. While these carriers also provide the opportunity for a range of delivery strategies, release mechanisms, targeting modalities, and pharmacokinetic profiles, the most important rationale for their use stems from the observation that these high molecular weight carriers improve accumulation within solid tumors compared to free drug via the enhanced permeability and retention (EPR) effect and reduce accumulation in healthy tissues [8, 9]. The EPR effect arises from the rapid pathological development of the tumor vasculature, which results in highly porous vessel walls lacking the tight junctions found in healthy tissue [10]. Thus, many macromolecular drug carriers that are excluded from healthy tissues are able to extravasate across the leaky tumor vasculature, while the lack of lymphatic drainage in tumor tissue leads to enhanced retention of these delivery vehicles.

Macromolecular polymers provide a wide array of advantages for drug delivery. First, they can extend the circulation half-life of the drug by simply increasing the apparent molecular weight of the drug [11]. This decreases the rate of clearance of the drug and of its nonspecific absorption into systemic tissues. Extending the plasma half-life also increases tumor exposure and can hence increase the amount of drug that accumulates in the tumor by the EPR effect. Second, these carriers can specifically target tumor tissue, passively through the EPR effect [12, 13], or actively via targeting ligands [14] or by the application of focused mild hyperthermia to tumors [15], thereby increasing the efficacy and reducing the systemic toxicity of the drug. Third, for drugs that are covalently conjugated to a polymer, the presence of a covalent link between the drug and polymer provides a cleavable tether that can be tailored to release the drug in response to an active trigger (e.g., low pH in endo-lysosomal compartments). In the case of low MW, hydrophobic drugs, conjugation to a soluble carrier can also increase the solubility of the drug in plasma by many orders of magnitude, enabling administration of a higher dose [1]. In some cases, covalent conjugation of the drug to the carrier can also stabilize the metabolically active drug, thereby further increasing efficacy. Fourth, the presence of a hydrophilic corona can impart “stealth” characteristics by preventing opsonization by immune tissues and degradation by proteases. Some polymeric carriers also enhance the cytotoxicity of a drug by overcoming the cellular multidrug resistance exhibited by many solid tumors [16-18].

This review exclusively focuses on one specific macromolecular carrier that we have been developing for cancer therapy for the past decade – elastin-like polypeptides (ELPs). ELPs are a class of temperature sensitive biopolymers based on the structural motif found in mammalian tropoelastin [19, 20]. ELPs consist of a repeated pentapeptide sequence (VPGXG)n, where X is any amino acid except proline. ELPs exhibit a thermodynamic inverse phase transition in aqueous solution at a specific temperature (Tt), below which ELPs are soluble and above which ELPs become insoluble and form a coacervate phase. This phase transition is completely reversible.

ELPs retain all the advantages of polymeric drug delivery systems, but also provide a number of additional benefits that are unique to genetically engineered biopolymers. First, because ELPs are composed of amino acids, they are non-toxic [21] and biodegradable [22]. Second, ELPs have a favorable pharmacokinetic profile [23]. Third, because ELPs are designed and synthesized using genetic engineering techniques [24], the molecular weights of ELPs can be precisely specified resulting in monodisperse polymers, parameters that are critical to tune the pharmacokinetics of polymers. In contrast the MW and polydispersity of synthetic polymers is difficult to control with the same level of precision as recombinant peptide polymers. Fourth, their composition can also be precisely encoded at the gene level. This has the consequence that the degree of hydrophobicity and the degree of ionization of an ELP can be precisely tuned, both of which impact its tissue distribution and sub-cellular uptake. Control over the ELP sequence also allows the numbers and locations of reactive sites for drug conjugation to be precisely specified, which allows the architecture of an ELP-drug conjugate to be controlled at the sequence level. Fifth, ELPs can be easily expressed at high yield (100-200 mg/L) from E. coli and rapidly purified by exploiting their phase transition behavior [25, 26].

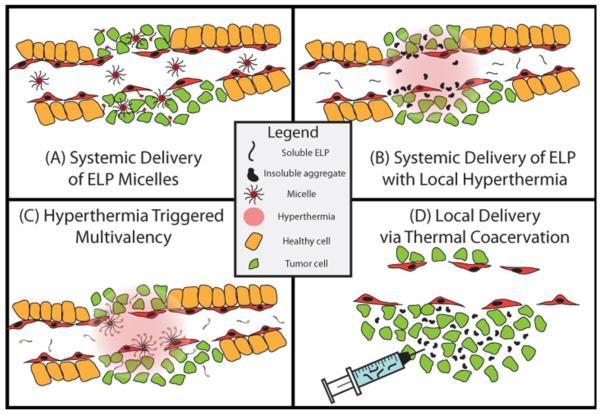

These properties of ELPs have provided the motivation for our group's development of ELP-derived drug carriers for both systemic and local delivery (Figure 1) using a number of different strategies. In the first and perhaps simplest “passive targeting” strategy, hydrophilic ELPs with a Tt much greater than body temperature (Tb) can be used as soluble, hydrophilic macromolecular carriers of conjugated drugs to take advantage of the EPR effect for systemic delivery [27]. In a second “thermal targeting” strategy that builds on the first approach, ELPs can be designed to exhibit a Tt between 37 °C and 42 °C; systemic delivery of these ELPs in combination with externally applied, local hyperthermia to a solid tumor leads to enhanced tumor accumulation as compared to passive EPR-driven accumulation [28]. This approach exploits the ELP phase transition to trigger the aggregation of drug carriers in the tumor vasculature. The formation of ELP microparticles that adhere to the tumor vasculature due to hydrophobic interactions enhances the concentration gradient between the vasculature and the tumor and increases ELP diffusion into the tumor once the aggregates dissolve upon return to normothermia. This approach successfully increases the tumor accumulation of the ELP-drug conjugate and decreases systemic toxicity; repetition of hyperthermia cycles results in a greater increase in tumor accumulation compared to an ELP control that does not go through its phase transition in this temperature window (Tt ≥≥ Th) [29]. Third, ELP block copolymers can be designed to form nanoparticle micelles specifically within the tumor vasculature in response to hyperthermia, resulting in multivalent display of ligands on the micelle corona [30]. Fourth, ELPs are useful vehicles for local delivery of drugs by intratumoral injection, as ELPs can be designed to be soluble and injectable at room temperature but to coacervate at physiological temperatures. Intratumoral injection of an ELP-radionuclide results in the in situ formation of an ELP depot that increases the length of exposure of the tumor to conjugated radiotherapeutics, and results in a significant tumor growth delay [31]. The remainder of this article discusses these four approaches in greater detail.

Figure 1. ELP drug delivery strategies.

This figure depicts four strategies that use ELPs to deliver drugs to a solid tumor in vivo. (A) Drug attachment triggered self-assembly of an ELP into micelles. Hydrophobic drugs are attached to the C-terminus of a hydrophilic ELP to trigger the self-assembly of micelles. These micelles accumulate in the tumor by passive diffusion through the leaky tumor vasculature. (B) Thermal targeting of an ELP to a heated tumor by the phase transition triggered aggregation of the ELP in tumor vasculature. ELP-drug conjugates can be actively targeted to a tumor by using the ELP phase transition in combination with the application of mild hyperthermia to the tumor to trigger formation of micron sized aggregates of the ELP that adhere to the vessel walls. Upon cessation of hyperthermia, the aggregates dissolve, generating a large concentration gradient that drives the ELP that dissolves from the aggregates into the tumor. (C) Multivalent targeting of a solid tumor by thermally triggered self-assembly of a diblock ELP into micelles in a heated tumor. Focused mild hyperthermia of a solid tumor can be used to thermally trigger the self-assembly of diblock ELPs into micelles that display a tumor targeting ligand on the corona of the micelle. In ELP unimers, the ligand is monovalent and hence has low avidity, which does not lead to significant ELP uptake by cells. In the thermally triggered micelle state, multivalent presentation of the ligand leads to high avidity and greater uptake by cells. (D) Local delivery of an ELP that coacervates in a solid tumor upon intratumoral injection. An ELP with a Tt below body temperature can be directly injected into a tumor to form an insoluble coacervate which forms a long-lasting depot, which extends the exposure of a conjugated radiotherapeutic to the tumor.

2. Systemic delivery of soluble ELP micelles

Over the past few decades, a significant amount of research has focused on drug-loaded nanoparticles such as liposomes [5], micelles [6], and polymeric nanoparticles [32]. These systems generally display many of the favorable in vivo attributes of macromolecular carriers, such as a longer plasma half-life and greater accumulation in the tumor than free drug, while also increasing the solubility of the drug. Polymers can also be designed to form useful supramolecular systems with improved pharmacological profiles over those exhibited by polymer-drug conjugates. For example, in an aqueous environment, amphiphilic diblock polymers – polymers with spatially separated hydrophobic and hydrophilic segments – can self-assemble into micelles with a hydrophilic corona and a hydrophobic core. Polymer micelles are useful for drug delivery because the hydrophobic core can sequester and solubilize small, hydrophobic drugs [6] while the hydrophilic corona can prevent uptake by the reticular endothelial system [13]. The sub-100 nm size of polymer micelles enables efficient extravasation into tumors via the EPR effect [33]. Polymer micelles can encapsulate a wide range of drugs, and can be designed for triggered drug release [1, 6, 34].

Most previous studies have either focused on the physical encapsulation of drugs into diblock amphiphilic polymers that form micelles, or on the synthesis of polymer-drug conjugates where the drug is chemically attached to the polymer, but the polymer does not necessarily self-assemble into a nanoparticle that sequesters the drug. Both approaches have their advantages and disadvantages. Polymer micelles with physically encapsulated hydrophobic drug within the hydrophobic core can liberate the drug during micelle disassembly due to dilution below the critical micelle concentration (CMC), or via a programmed trigger. While the simplicity of physically encapsulated drugs is attractive, the types of drugs that can be encapsulated are strongly dependent on the material properties of the polymers that comprise the polymer micelle. In contrast, drug conjugates of synthetic polymers are more forgiving in the choice of drug and the degree of drug loading as a consequence of drug attachment to the polymer. However, these systems typically do not provide much control over the location and number of attached drugs along the polymer backbone, creating a polydisperse conjugate with a variable degree of drug loading that may or may not protect the drug from the environment during its transit though the body.

Seeking to combine the advantages of both systems, we sought to design a system wherein conjugation of a drug to a polymer drives its self-assembly into a nanoparticle. We hypothesized that the attachment of many copies of small hydrophobic molecules such as chemotherapeutics to the C-terminus of a hydrophilic ELP would impart the necessary amphiphilicity to drive self-assembly of the polypeptide-drug conjugate into nanoparticles [27]. To test this hypothesis, we first selected ELP[VA8G7]-160 as the ELP that would form the corona of the micelle, where the letters in brackets indicate the guest residue composition and the number indicates the number of pentapeptides. We chose this ELP because we previously showed that this ELP has the capacity to solubilize conjugated molecules in aqueous plasma [35], that it displays favorable pharmacokinetics (2.5% degradation/day in serum), and has an extended half-life in vivo (~9 hours) [23]. A short peptide consisting of Cys-(Gly-Gly-Cys)7 was appended to the C-terminus of the ELP to provide multiple, unique sites for drug attachment (cysteine residues), thus forming a chimeric peptide (CP) with a hydrophilic ELP segment followed by a short, cysteine-rich drug attachment segment. Diglycine spacers were included in the drug attachment segment to minimize steric hindrance between conjugated drug molecules.

Doxorubicin (Dox) was selected as the chemotherapeutic because it is a clinically effective hydrophobic drug with dose limiting side effects, including cardiomyopathy and congestive heart failure [36, 37]. Dox has shown a high level of effectiveness upon conjugation to macromolecular carriers in preclinical trials [38], and has been physically encapsulated in micelles [39-41]. We hypothesized that sequestration of Dox into the core of a micelle upon attachment to the Cys residues in the CP would therefore limit the toxicity to healthy tissues while targeting the drug to tumor tissues via the EPR effect. Dox was conjugated to n-ß-maleimidopropionic acid hydrazide tri-fluoroacetic acid (BMPH), an acid-labile hydrazone based linker containing a terminal maleimide, and was then conjugated to the CP via a maleimide-thiol reaction, thus utilizing the cysteine residues as conjugation sites. This pH-sensitive linker was chosen because it has been shown to selectively cleave [42-45] in the acidic environment of endosomes and lysosomes [46], enabling drug release from the polymer following cellular uptake and subsequent nuclear delivery. The purified conjugate had ~ 6 Dox molecules attached to each chimeric peptide (CP).

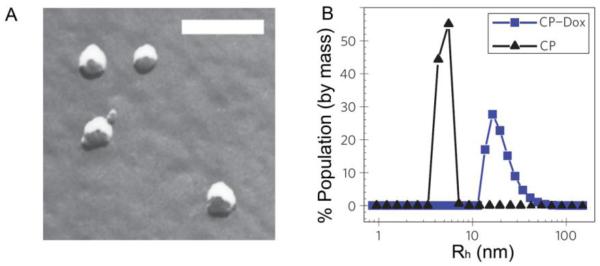

Genetically encoded synthesis of this CP was critical, as it allowed the drug attachment sites–multiple, evenly spaced cysteine residues– to be located on one end of the CP so that the site of drug conjugation was restricted to the C-terminus of the CP, and it also allowed the number of drug molecules conjugated per CP to be strictly controlled. Upon conjugation of multiple Dox molecules to the end of the CP (~6 out of a maximum of 8 attachment sites), the resulting amphiphilicity of the CP-Dox conjugate led to micelle formation, which was validated by freeze fracture scanning electron microscopy (ff-SEM) and dynamic light scattering (DLS) (Figure 2). Small spherical nanoparticles were observed by ff-SEM with a radius of 19.3 ± 0.9 nm (Figure 2A). DLS measurements confirmed the formation of a monomodal population of nanoparticles with a mean Rh = 21.1 ± 1.5 nm; in contrast, the unconjugated CP had an Rh of 5.5 ± 0.9 nm (Figure 2B). The 40 nm diameter of the CP-Dox nanoparticles is well below the 100 nm pore size found in the vasculature of most solid tumors [47], suggesting that these CP-Dox micelles should selectively extravasate and accumulate in tumors via the EPR effect. DLS of CP-Dox as a function of concentration indicated that the critical aggregation concentration for these nanoparticles is ~3 μM, suggesting long-term micelle stability in the blood, as the plasma concentration following injection in vivo was 125 μM CP. Further supporting the conclusion that these micelles are stable in blood, DLS measurements indicated that the CP-Dox micelles were stable for over 24 hours in the presence of 1 mM bovine serum albumin at physiological pH.

Figure 2. Characterization of CP-Dox nanoparticles.

CP-Dox nanoparticles characterized by: (A) freeze fracture scanning electron microscopy (bar = 200 nm) and (B) dynamic light scattering at 25 μM in PBS at 37 °C. DLS measures the distribution of hydrodynamic radii (Rh) [27].

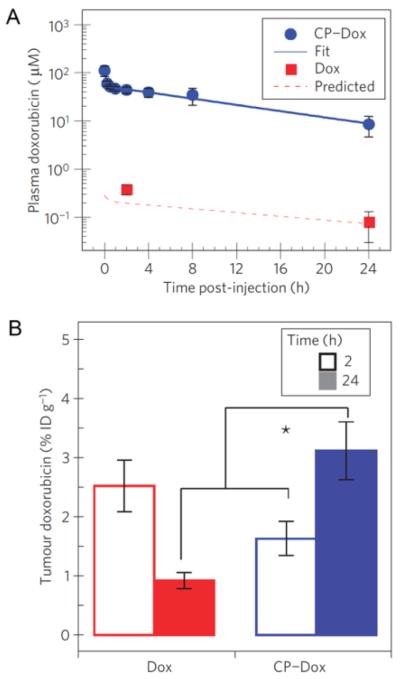

To evaluate the utility of CP-Dox as a drug delivery vehicle, mice were intravenously injected with CP-Dox or Dox (control), and the Dox concentration in plasma was measured over time (Figure 3A). The data were fit to a two compartment pharmacokinetic model, which yielded a CP-Dox terminal half-life of 9.3 ± 2.1 hours and a plasma AUC of 716 ± 139 μM h. This demonstrated a significant increase in plasma retention over free drug, which had an AUC of 4.7 μM h [48]. The biodistribution of CP-Dox versus Dox was also tested at 2 and 24 hours post injection (Figure 3B). CP-Dox showed a 3.5-fold increase in tumor concentration after 24 hours over free drug, and a 2.6-fold decrease in heart concentration after 24 hours. This decreased cardiac exposure is clinically significant, as Dox suffers from dose-limiting cardiomyopathy.

Figure 3. Plasma pharmacokinetics and tissue biodistribution.

(A) Plasma concentration of Dox as a function of time post-injection. Lines represent a two-compartment model fit. Error bars indicate the 95% confidence interval (n=5). (B) Dox concentration in tumor tissue. * p < 0.0005 Analysis of Variance, Tukey's HSD. Data are presented as mean ± SD [27].

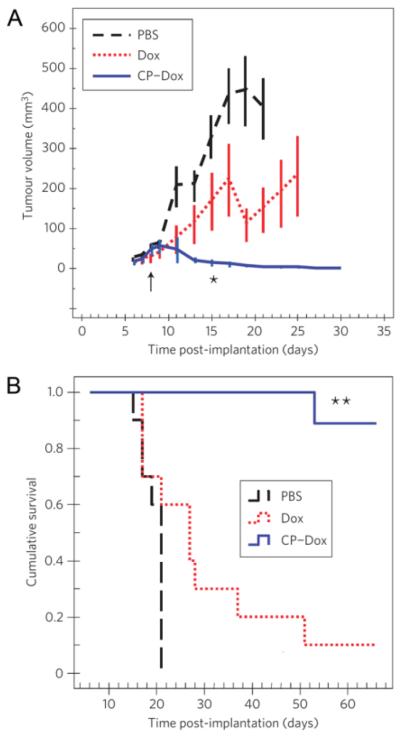

Next, a dose-escalation study revealed that the maximum tolerated dose (MTD) of CP-Dox was 20 mg/kg Dox, versus 5 mg/kg for free Dox. This increase is likely due to the reduced accumulation of CP-Dox in the heart. Then, CP-Dox was evaluated for its anti-tumor efficacy at its maximum tolerated dose (MTD). Mice with 8-day old dorsal subcutaneous C26 colon carcinomas were intravenously injected with CP-Dox at 20 mg/kg Dox, Dox at 5 mg/kg, or PBS. The tumor volume was measured for 30 days post tumor implantation, at which point CP-Dox, with an average tumor volume of 13 mm3, significantly outperformed Dox (166 mm3) and the PBS control (329 mm3) (Figure 4A). This tumor size reduction also correlated with mouse survival (Figure 4B). Median survival for PBS-treated mice was 21 days, which only increased to 27 days for the Dox treated mice. In contrast, eight of the nine CP-Dox treated mice experienced tumor-free survival until the end of the study, 66 days post tumor implantation.

Figure 4. Anti-tumor activity of CP-Dox nanoparticles.

(A,B) Tumor cells (C26) were implanted subcutaneously on the back of the mice on day zero. Mice were treated on day 8 (↑) at the MTD with PBS (n=10), free Dox (5 mg / kg BW; n=10), or CP-Dox (20 mg Dox equivalent/ kg BW; n=9). a) Tumor volume up to day 30 (for n > 6). Error bars represent the SEM. *indicates p= 0.03, 0.00002 for CP-Dox vs. Dox and CP-Dox vs. PBS (day 15), respectively (Mann Whitney). b) Cumulative survival of mice **indicates p = 0.0001, 0.00004 for CP-Dox vs. Dox and CP-Dox vs. PBS, respectively (Kaplan- Meier) [27].

3. Systemic delivery of ELP with local hyperthermia

While passive EPR tumor targeting effectively increases the amount of drug delivered to the tumor, the thermal responsiveness of ELPs can be exploited for active targeting to tumors by focused, local hyperthermia of solid tumors. Thermal targeting of ELPs is hence complementary to passive targeting. Because the Tt of ELPs is exquisitely sensitive to the ELP composition and MW, parameters that can be precisely specified at the gene level, ELPs can be rationally designed to exhibit a Tt that is intermediate between body temperature (Tb = 37 °C) and the upper limit of mild hyperthermia (Th = 42 °C). We therefore designed an ELP with a Tt between 37 °C and 42 °C (Th), so that the ELP remained soluble upon i.v. injection but underwent its phase transition and formed insoluble aggregates in a tumor that was heated locally to 42 °C.

We hypothesized that this approach would combine the favorable pharmacokinetics and passive targeting features of polymer drug carriers with increased accumulation of the thermally sensitive polymer-drug conjugate afforded by its local aggregation within a heated tumor. This approach is also attractive because it acts in concert with the benefits of mild hyperthermia for cancer therapy. Hyperthermia has been used clinically as both a stand-alone strategy and as an adjuvant for radiation therapy [49]. However, ablating tumor tissue requires high temperatures (> 43 °C) that can result in edema and necrosis in nearby tissues [50]. Although mild hyperthermia (40 °C - 43 °C) does not directly kill tissue, it has been shown to sensitize the tumor to chemotherapeutics as well as to increase vascular permeability and tumor blood flow compared with normal vasculature, thereby increasing the extravasation of macromolecules [51, 52]. From the perspective of clinical implementation, mild hyperthermia has been used on human patients as an adjunct to external beam radiotherapy and chemotherapy [49], so that the regulatory hurdles of implementing thermal targeting are likely to be far lower than other targeting modalities that have not been approved for human use.

There are a variety of clinical procedures by which a solid tumor can be specifically heated. Commonly used modalities for the delivery of focused, mild hyperthermia involve the use of microwaves, ultrasound [53], and radiofrequency waves to deliver heat to the surrounding tissue. For external heat delivery to a superficial tumor, microwave and radiofrequency applicators are generally placed on the surface using a contact medium. This provides control over the tumor temperature for depths up to a few centimeters, and thus is only used in situations where the tumors are easily accessible. Deeply seated tumors can be heated by internal interstitial methods that require surgery to insert probes within the tumor. This method is highly invasive as it requires meticulous placement of multiple heat applicators throughout the tumor. Endocavitary methods are used for tumors that are near body cavities such as the oesophagus, rectum, or prostate. The utilization of these body cavities for insertion into the tumor allows large probes with greater penetration depths than those used for interstitial insertion. Both endocavitary and interstitial treatments make use of microwave antennas, high intensity focused ultrasound transducers (HIFU), radiofrequency electrodes, or a number of other devices such as hot water tubes or ferromagnetic seeds in order to specifically focus heat on the tumor tissue [54].

The ELP phase transition temperature is sensitive to a number of variables, including the ELP guest residue composition, chain length, and polypeptide concentration – each of which must be considered when developing a carrier with the desired thermal properties. The first step in developing a thermally sensitive carrier with a Tt between Tb and Th was to generate multiple ELP libraries with varying guest residue compositions. Three ELP libraries were synthesized by recursive directional ligation (RDL) [24], expressed in E. coli and purified by multiple rounds of inverse transition cycling (ITC). The thermal transition behaviors of the ELPs in each library were quantified with respect to their chain length and ELP concentration. The Tt was shown to be inversely proportional to the chain length, so that short ELPs (10 kDa) have dramatically higher Tts than longer ELPs (60 kDa), consistent with previously published data from Urry et al. [55]. These results also confirmed that the Tt shows an inverse logarithmic dependence on ELP concentration [56]. The concentration dependence of the Tt is a critical design parameter because it can determine the ultimate fate of the polymer-drug conjugate. If the initial injected dose is too high, the Tt may be depressed below Tb, inducing precipitation and aggregation throughout the body instead of limiting the transition to the tumor vasculature. This undesirable outcome would not only decrease the dose delivered to the tumor, but would also increase systemic toxicity. If the injected dose of ELP is too low, however, the Tt may be elevated above Th, preventing thermally triggered aggregation in the tumor vasculature. Furthermore, the Tt will increase with time as the injected ELP is slowly cleared from the circulation by degradation and excretion, but because the dependence of Tt on concentration is logarithmic, the acceptable concentration range is large (one order of magnitude). This suggests that the ELP should remain in the appropriate concentration range to exhibit thermally triggered aggregation within a heated tumor for a reasonable amount of time, on the order of a few hours post-injection.

These studies narrowed the choice of the thermally sensitive ELP to ELP[V5A2G3-150] (ELP1; 59.4 kDa), which has a Tt between 37 °C and 42 °C at clinically relevant concentrations (3 – 30 μM) in mouse plasma [35]. ELP[V1A8G7-160] (ELP2, 61.1 kDa, 160 pentapeptides) was selected as a thermally insensitive control because it had a similar molecular weight to ELP1 but would not aggregate in the heated tumor vasculature, as its transition was above 55 °C within a similar concentration range.

These two constructs were then conjugated to rhodamine and intravenously injected into athymic mice containing 2-3 mm3 human ovarian carcinomas (SKOV-3) implanted within a dorsal skin flap window chamber. The window chamber model allows for real-time optical imaging within the vascular and extravascular space of the implanted tumor [57, 58]. The window chamber, which was connected to a temperature controlled water bath, was held at 34 °C (the subcutaneous temperature in mice) or placed under mild hyperthermia (42 °C). The window chamber was viewed under epi-illumination using fluorescence videomicroscopy, revealing that the rhodamine-labeled temperature sensitive ELP1 formed aggregates that attached to the vessel walls at 42 °C but not at 34 °C. The temperature insensitive ELP2 did not form aggregates at 42 °C. This study was the first demonstration that a thermally sensitive polymer could be designed to transition at a specific temperature in vivo.

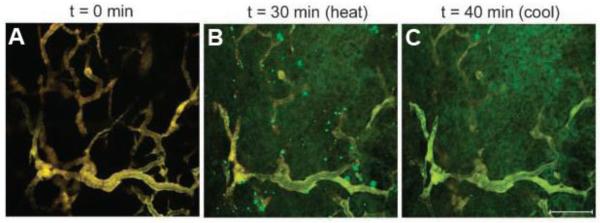

Dreher et al. further quantified the effect of mild hyperthermia on the biodistribution of ELP1 and ELP2 within the window chamber tumor model using intravital confocal fluorescence microscopy [29], which allowed imaging of the tumor with much better spatial resolution than conventional fluorescence microscopy. ELP1, labeled with Alexa-488 (green), and ELP2, labeled with Alexa-546 (red), were intravenously coinjected into the mice. Under normothermic conditions, both ELPs colocalized as soluble polymers within the tumor vasculature as seen by homogeneous yellow fluorescence, which was consistent with the fact that neither ELP was expected to undergo its phase transition under these conditions (Figure 5A). In implanted tumors that were heated to 41.5 °C, the temperature sensitive ELP1 formed bright green aggregates that adhered to the vessel wall and continued to grow in number and size throughout the 30 minute incubation period (Figure 5B). No red aggregates of ELP2 were observed, indicating that the aggregation of ELP1 was solely driven by its thermal phase transition. Upon cessation of hyperthermia, the green aggregates dissolved into the plasma, demonstrating the reversibility of the phase transition (Figure 5C). The more intense green color within the extravascular space of the tumor at the end of the experiment indicated that there was greater accumulation of the thermally sensitive ELP1 in the tumor due to its phase transition, when compared with the thermally insensitive control ELP2. These results qualitatively suggested that systemic injection of a thermally sensitive ELP in combination with mild hyperthermia of a tumor can increase its tumor accumulation beyond the passive accumulation of soluble ELP in a tumor that results from the EPR effect.

Figure 5.

Images of thermally sensitive ELP1 (green) and thermally insensitive ELP2 (red) in a solid tumor before, during, and after hyperthermia treatment. The vascular intensities of the ELPs in (A) were balanced to produce a yellow color. (A) 0 min, before heat application. (B) 41.5 °C, after 30 minutes of heat application. The green punctate fluorescence indicates aggregation of ELP1. (C) 37 °C, after 10 minutes of cooling. The absence of punctate fluorescence in (C) as compared to (B) demonstrates the reversibility of ELP1's phase transition. The bar represents 100 μm in all images [29].

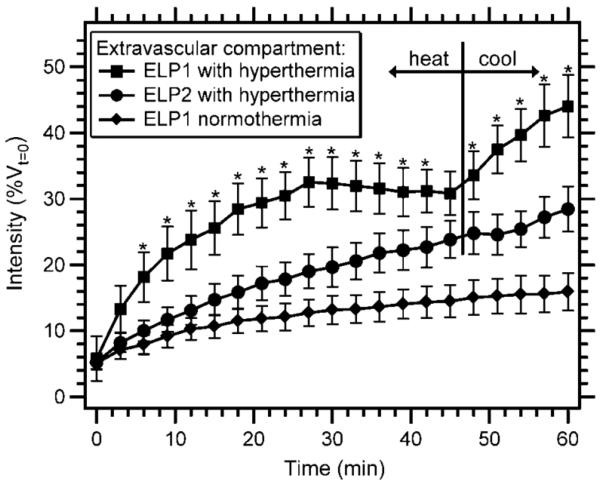

Dreher et al. then proceeded to quantitatively test the hypothesis that the dissolution of the particles upon cooling would result in an increased vascular concentration of ELP1 relative to its aggregated state prior to cessation of hyperthermia, providing an enhanced driving force for diffusion of the thermally sensitive polymer into the extravascular space. This hypothesis was tested by quantifying the distribution of ELPs in the extravascular space over the course of 45 minutes of hyperthermia followed by 15 minutes of normothermia. Mild hyperthermia resulted in a slightly higher rate of extravascular accumulation of the temperature sensitive ELP1 compared with the temperature insensitive ELP2 (Figure 6). However, upon cooling to 37 °C, the rate of extravasation of the thermally sensitive ELP1 rapidly increased, whereas the extravasation rate of the thermally insensitive ELP2 remained constant. After this single 60 minute cycle of hyperthermia and return to normothermia, ELP1 with hyperthermia showed a 1.6-fold increase in extravascular intensity over the thermally insensitive ELP2 with hyperthermia, and a 2.8-fold increase over ELP1 without hyperthermia. These experiments clearly showed that the increased vascular concentration of ELP1 aggregates that adhered to the vessel walls in the tumor during hyperthermia led to a higher rate of transvascular transport upon return to normothermia as the aggregates dissolved, and suggested that multiple cycles of hyperthermia would result in a further increase in tumor accumulation. Circumstantial confirmation of this hypothesis was provided by the observation that ELP1 could be successfully aggregated in the heated tumor vasculature over the course of three cycles of hyperthermia [29].

Figure 6.

Extravascular accumulation of a thermally sensitive ELP with hyperthermia treatment as a function of time. Data were normalized by the initial vascular intensity for each animal and expressed as a percentage of vascular intensity at t = 0 min. The tumor was not heated for the ELP1 normothermia control. The tumor was heated to 41.5 °C for the first 45 min and then cooled to 37 °C for the remaining 15 min for the ELP1 hyperthermia and ELP2 hyperthermia conditions. The data are expressed as mean ± SE. *, P<0.05, Fisher's PLSD for ELP1 with hyperthermia versus ELP2 with hyperthermia [29].

Stable radioisotope labeling methods have also been used to quantitatively analyze the biodistribution and pharmacokinetics of intravenously injected ELPs [23]. This method, based on homogeneous metabolic 14C labeling of the ELP during expression, enables facile tracking of the in vivo fate of the ELPs and their degradation products while avoiding artifacts resulting from premature cleavage of a conjugated radiolabel. ELP1 and ELP2 were both labeled using this method, and the pharmacokinetics of ELP1 were analyzed in mice, yielding a terminal plasma half-life of 8.4 hours.

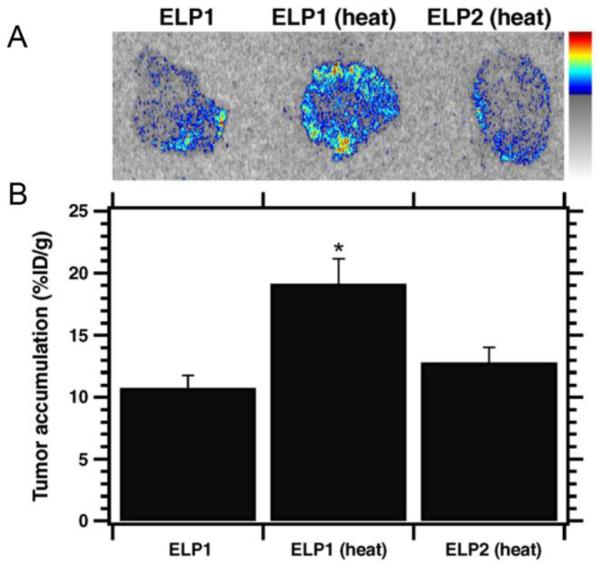

The two labeled ELPs were then injected into nude mice (Balb/c nu/nu) bearing flank FaDu xenografts, both with and without application of localized mild hyperthermia. After one hour, the tumors were resected and imaged using autoradiography (Figure 7A). A 1.8-fold increase in the tumor accumulation of ELP1 was observed in mice with tumors that were heated as compared to animals that were injected with the same ELP but whose tumors were not subjected to hyperthermia, and a 1.5-fold increase was observed for ELP1 with hyperthermia compared to ELP2 with hyperthermia (Figure 7B). Additionally, ELP1 with hyperthermia resulted in a more uniform distribution of ELP throughout the tumor than either control.

Figure 7.

(A) Autoradiography images of 20 μm tumor sections after 1 hr of hyperthermia treatment with 14C labeled ELP1 with and without heat, and 14C labeled ELP2 with heat. (B) Scintillation analysis of the tumor sections shows that ELP1 with heat results in significantly greater accumulation than either of the controls. Data are shown as mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05, Fisher's PLSD [23].

4. Hyperthermia-triggered multivalency

A common method for improving drug accumulation beyond the EPR effect is to create macromolecular carriers with appended ligands, such as RGD, NGR, or folate, that target a specific cellular receptor or membrane protein that is upregulated by tumor cells or the tumor vasculature. This active targeting can result in an improvement in both the specificity of the drug for the tumor and its accumulation [14, 59-61]. However, the effectiveness of high affinity ligands is limited by their systemic toxicity, as their high affinity also promotes their interaction with the same receptor that is expressed in healthy tissues, albeit at lower levels [62, 63]. While multivalent ligand presentation can increase the avidity of receptor-ligand interactions, multivalent drug carriers experience the same problem of increased off-site targeting with increased affinity [59]. Therefore, the use of a stimulus to trigger tumor-specific multivalent display of a drug delivery vehicle could be an effective approach to enhance binding of the drug delivery vehicle in the tumor without increasing its accumulation in healthy tissues.

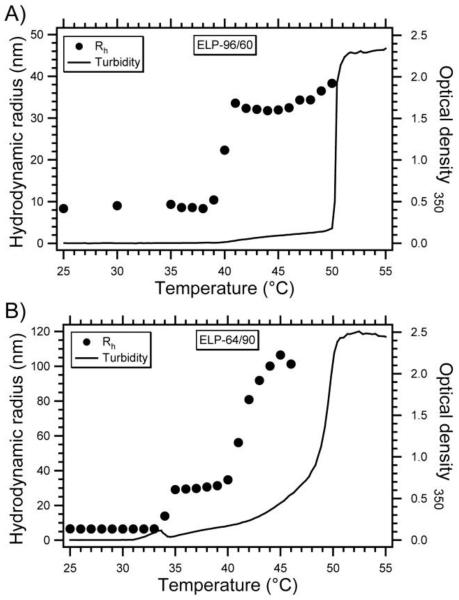

To this end, our group synthesized ELP block copolymers (ELPBCs) with an N-terminal ligand designed to self-assemble into multivalent micelles only in solid tumors that were subjected to mild hyperthermia [30]. The design of a diblock ELP with hydrophobic guest residues in the C-terminal block [V5] and hydrophilic guest residues in the N-terminal block [VA8G7] resulted in an ELP that exhibited independent thermal transitions of the two blocks, defined as Tt1 and Tt2, respectively. Turbidity profiles and dynamic light scattering (DLS) as a function of solution temperature demonstrated a three-stage thermal behavior of this class of diblock ELPs (Figure 8). At a temperature below the transition temperature of both blocks, these ELPs exist as soluble ”unimers”, with an Rh of 5 – 10 nm consistent with the size of a well-solvated polymer chain. At a solution temperature greater than Tt1 but below Tt2, the hydrophobic block undergoes its phase transition but the more hydrophilic block does not, imparting an amphiphilic character to the diblock ELP. This temperature-triggered amphiphilicity drives the self-assembly of these ELPBCs into monodisperse spherical micelles, which can be detected by UV-vis spectrophotometry as a small increase in turbidity (OD350nm < 0.1) and by dynamic light scattering, which reports a hydrodynamic radius (Rh) ranging from 30-40 nm depending on the overall molecular weight and the size ratio of the two blocks. Performing DLS and static light scattering (SLS) at multiple angles demonstrated that these nanoparticles are hard spherical micelles, a finding supported by cryo-transmission electron microscopy. Pyrene, a small molecule probe that fluoresces based upon the polarity of its local environment, was used to show that the critical micelle concentration (CMC) of these ELPBC micelles ranged from 4-8 μM, a level of stability that is suitable for i.v. drug delivery.

Figure 8. Thermally-triggered self-assembly of ELPBC micelles.

Optical density at 350 nm and hydrodynamic radius (Rh) of (A) 25 dμM ELP[VA8G7-96]/[V5-60] and (B) ELP[VA8G7-64]/[V5-90] in PBS versus temperature [30].

Above Tt2, the second block also goes through its phase transition, which abrogates the amphiphilicity of the diblock ELP and leads to the formation of polydisperse micron-sized aggregates. The temperature-triggered self-assembly of these diblock ELPBCs was controlled by the hydrophilic to hydrophobic block length ratio and the total chain length of the ELP. For example, longer ELPBCs had a lower Tt1 than a shorter ELPBC with the same block ratio, and Tt1 was also lower for ELPBCs of the same length but greater hydrophobic content. Likewise, the Rh was larger for nanoparticles formed from longer ELPs or those with greater hydrophobic content. These findings, together with the ability to tune each transition temperature at the sequence level, allowed us to design ELPBCs that self-assemble into micelles only under conditions of mild hyperthermia.

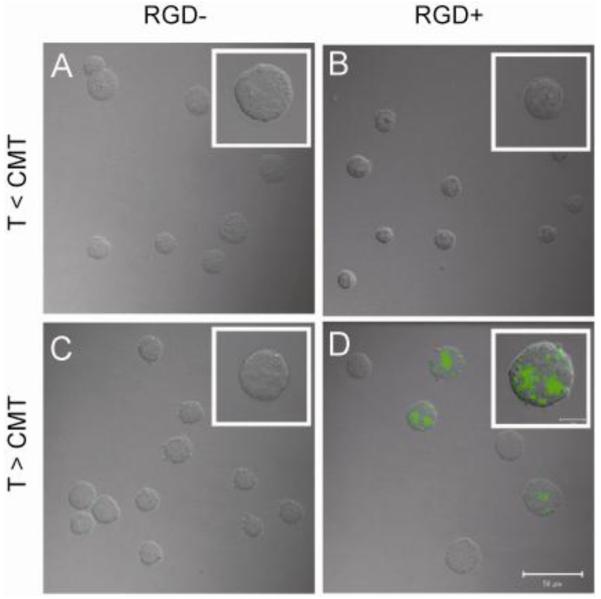

Genetically appending the peptide ligand to the hydrophilic sequence at the N-terminus ensured that the micelle surface displayed multiple copies of the targeting ligand, with the copy number estimated to range from 56-133 based upon the apparent molecular weight of the micelle as determined by SLS. Appending the RGD and NGR peptide ligands on the N-terminus of ELPBCs did not perturb self-assembly or the stability of the micelle. Thermally-triggered affinity modulation was then demonstrated using RGD-presenting ELPBCs and K562 human leukemia cells that were stably transfected to express the RGD-binding integrin αvβ3[64]. Flow cytometry demonstrated a 14-fold increase in uptake by integrin-expressing cells of the optimal RGD-ELPBC above its assembly temperature (CMT, or critical micelle temperature) compared with below its CMT. The same temperature increase only led to a 3-fold increase in uptake of the same polymer by integrin-negative cells, and both cell types demonstrated a 3-fold increase in uptake of ELPBCs with heat. Taken together, these results suggested that a ~5-fold increase in specificity of uptake was achieved by thermally-triggered multivalency, and demonstrated that this effect specifically depends on nanoparticle assembly, ligand presentation, and receptor expression. These effects were confirmed using confocal microscopy (Figure 9). Studies are in progress to quantitatively characterize the effect of hyperthermia on the tumor accumulation of ligand-presenting ELPBCs using window chamber microscopy in an effort to develop hyperthermia-triggered multivalent ligand display as an effective drug delivery strategy. In summary, ELPs present distinct advantages for thermally triggered multivalent targeting of tumor vasculature: genetically encoded synthesis of ELPs provides uniform block lengths, which in turn results in micelles with highly homogenous size distributions; ELP-peptide fusions on the genetic level allow peptide ligands to be easily encoded into the biopolymer sequence without the need for a separate conjugation step; and control over the ELP composition allows the thermally triggered self-assembly to be precisely tuned.

Figure 9. Thermally-triggered multivalency increases uptake of ELPBC micelles.

Alexa488-labeled ELP[VA8G7-64]/[V5-90] without (A,C) and with (B,D) an N-terminal RGD ligand were incubated at 10 μM for 1 h with K562 cells expressing αvβ3 below (A,B) and above (C,D) the CMT of the ELPBC. Confocal microscopy demonstrates that significant uptake only occurred when the RGD-presenting ELPBC was incubated above its CMT (D) [64].

5. Local delivery via thermal coacervation

Intratumoral (i.t.) drug delivery is an alternative to systemic drug delivery for therapy of solid tumors because it circumvents the problems inherent in systemic drug delivery –low tumor penetration, rapid drug clearance and exposure to healthy tissues– by retaining the anti-cancer therapeutic within the tumor for an extended period of time. This can potentially result in a high therapeutic concentration at the desired site of action and avoid the need for systemic administration and associated adverse effects [23, 31, 65-67]. I.t. administration is most clinically relevant in situations where surgery would have adverse complications [68, 69]; a reduction in tumor size is necessary prior to surgery; an eventual recurrence is likely, such as for glioblastomas [66]; or in situations where no more treatment options are available [70]. Intratumoral administration promotes optimal drug exposure by maximizing drug retention within the tumor. Therefore, a drug delivery depot that is injectable at room temperature but coacervates at body temperature represents a promising local delivery vehicle, particularly for radiotherapeutics, which are effective even in low concentrations.

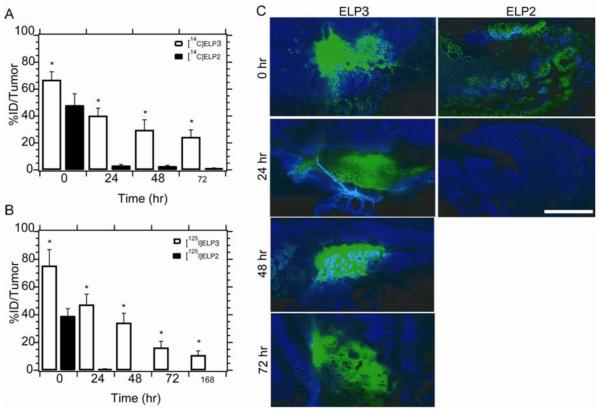

We investigated the feasibility of intratumoral therapy using ELPs by synthesizing two ELPs, both with a MW of ~50 kDa; one ELP (ELP3) was designed to have a Tt of 27 °C at our desired injection concentration of 500 μM, while the control ELP (ELP2) had a Tt of 63 °C at 500 μM. This latter ELP also served as the control for the thermal cycling experiments with systemically administered ELP described in the previous section. Both ELPs were labeled with 14C along the backbone of the polymer during expression, or radioiodinated via conjugation with a C-terminal tyrosine. Incubation in plasma revealed that thermally induced aggregation resulted in a significant decrease in the rate of 125I release of the thermally sensitive ELP3 relative to the thermally insensitive ELP2,with < 3% released from ELP3 after one week compared with ~ 30% from ELP2 over the same time period [31]. These results clearly suggested that the formation of a coacervate of ELP3 within the tumor retarded its deiodination, relative to soluble ELP2, which was avidly attacked by deiodinases in vivo. The 14C or 125I labeled polymers were then injected directly into FaDu (14C) or 4T1 (125I) tumors implanted subcutaneously (s.c.) in Balb/c nu/nu mice. The needle was placed at the center of the tumor, and injection of 20 μL was performed using a syringe pump at 4 μL/min. Tumor retention was monitored at 168 h following injection by sacrificing the animals, collecting their tumors, measuring their radioactivity, and expressing the retained activity as a percentage of the injected dose. The results presented in Figure 10 show that less than 5% of the thermally insensitive ELP2 remained in the tumor after 24 h, compared with over 40% of the thermally sensitive ELP3. Roughly 10% of ELP3 remained at one week following injection [31], at which time no ELP2 could be detected within the tumor. Analysis of these data using a one-compartment model indicated that ELP3 had a tumor half-life of 44 h compared with 8 h for the thermally insensitive ELP2, resulting in a 60-fold higher area under the curve of tumor exposure versus time [31]. Therefore, thermal coacervation of ELP following intratumoral injection successfully increased the exposure time of the radiotherapeutic, and decreased the release of active radiotherapeutics into the systemic circulation, in both tumor types.

Figure 10. Tumor retention of ELP coacervate.

(A) Tumor retention of 14C-ELPs following intratumoral administration to FaDu tumors implanted s.c. in Balb/c nu/nu mice. The radioactivity present in the tumor was measured using a beta-counter and expressed as the percentage of the injected dose. Data are presented as the mean, with error bars representing the SEM (n=8-10; *: p < 0.01, t-test). (B) Tumor retention of 125I-labeled ELPs following administration to 4T1 tumors as described above, measured using a gamma counter. (C) Fluorescence images of tumor sections following administration of ELPs labeled with Alexa-Fluor 488 (green), with Hoechst nuclear stain (blue) administered prior to sacrifice (scale bar = 100 μm) [31].

Next, ELPs labeled with Alexa-Fluor 488 by conjugation with a cysteine residue were injected as described to track the spatial distribution of the depot within the tumor. Following Hoechst administration, these tumors were collected, frozen in liquid nitrogen, sectioned, and imaged using a fluorescence microscope (Figure 10C). These results illustrate the rapid efflux of ELP2 out of the tumor and indicate that the spatial distribution of the ELP3 depot is consistent over time, suggesting the formation of a stable coacervate following intratumoral administration.

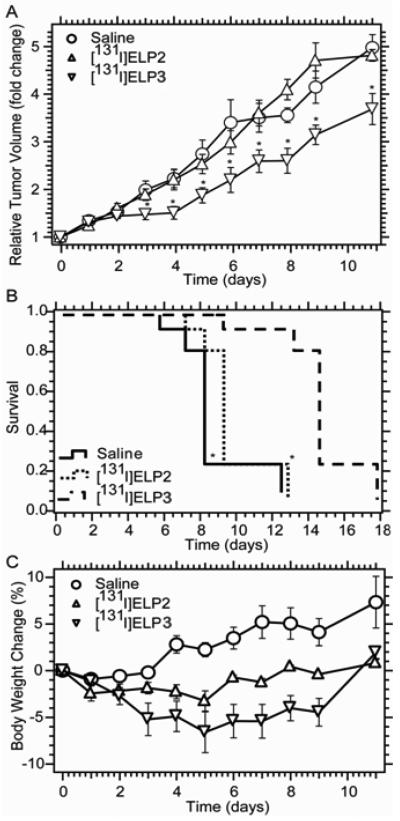

With these encouraging results in hand, the anti-tumor activity of thermally sensitive ELP3 labeled with the therapeutic radionuclide 131I was next examined. The thermally sensitive 131I-ELP3 demonstrated inhibition of 4T1 tumor growth versus mice treated with saline or radiolabeled thermally insensitive ELP2 (Figure 11A). The difference in tumor volume was significantly lower for the ELP3 group beginning on day 3 after treatment (p < 0.05, t-test). The tumor growth delay induced by 131I-ELP3 also correlated with mouse survival. It was found that the therapeutic prolonged survival for one week over saline administration (p < 0.01, Kaplan-Meier analysis; Figure 11B). Future work will seek to enhance this therapeutic effect by delivering higher radiotherapeutic doses, redesigning the ELP to prolong its tumor retention, and enabling multiple injections. It is important to note that this treatment was exceptionally well tolerated, with no animals displaying a body weight loss of more than 7% (Figure 11C). Also, collection of blood, heart, lungs, thyroid, liver, kidneys, spleen, muscle, and skin in the biodistribution study demonstrated no significant accumulation in any organs except for the tumor and thyroid, which is expected due to physiological iodine uptake by the thyroid [31]. Taken together, these results demonstrate that thermal coacervation of ELP represents a promising approach to local radiotherapy with low toxicity and a moderate efficacy that we believe can be significantly improved upon.

Figure 11. Antitumor efficacy of 131I-ELP coacervate.

(A) Relative volume of s.c. 4T1 tumors in Balb/c nu/nu mice following intratumoral administration of 131I-ELP3, 131I-ELP2-128, and saline, presented as the mean of n = 9 with error bars representing SEM (*: p < 0.05 vs. ELP2-128 or saline). (B) Kaplan-Meier analysis of survival, with 5x initial tumor volume defined as the endpoint. (C) Change in body weight following i.t. administration of 131I-ELP3, 131I-ELP2-128, or saline, presented as the mean of n = 9 with error bars representing SEM [31].

6. CONCLUSIONS

These studies demonstrate that elastin-like polypeptides are useful vehicles for both systemic and local drug delivery. Chimeric polypeptides derived from ELPs with hydrophobic drugs conjugated to the C-terminus self-assemble into nanoparticles that promote tumor regression in mouse models. Future work on systemic delivery of ELPs will focus on re-engineering chimeric drug-conjugated ELPs to shift their phase transition into the temperature range of mild hyperthermia in an effort to further enhance tumor accumulation. This development would combine the first and second modalities discussed in this review, thereby improving the efficacy of chimeric polypeptides by focusing accumulation of the drug carriers in the heated tumor. These chimeric polypeptides will also be conjugated with a variety of other chemotherapeutics to investigate the ability of this platform to deliver a range of drugs, and to explore synergistic effects between drugs that have complementary modes of action. In a third application of these polypeptides, hyperthermia-triggered multivalent display is a promising technique for enhancing the targeting of receptor-expressing cells, and work is in progress to characterize the effectiveness of this approach in vivo.

The fourth modality by which ELPs may be used for cancer therapy is intratumoral administration of an ELP-drug conjugate. We showed proof-of-principle of this approach by intratumoral administration of a radionuclide conjugated to a thermally sensitive ELP that coacervates at body temperature. Formation of an ELP coacervate led to increased retention of the ELP compared to a soluble ELP, which translated to a delay in tumor growth relative to controls. Future work will focus on enhancing this effect by increasing the amount of radiotherapeutic delivered per ELP, and by increasing the tumor retention by reengineering the ELP to enhance the stability of the coacervate within the tumor.

Each example described above takes advantage of the unique features of ELPs to improve drug delivery by a different mechanism. The precise, gene level control over the ELP sequence and MW enables the spatial distribution of drug attachment sites to be precisely specified along the ELP chain, thereby driving the self-assembly of the ELP-drug conjugate into nanoparticles that exhibit extended plasma circulation, high tumor accumulation, significantly greater tumor regression, and extended mouse survival compared to free drug. In the second approach we described, the ability to modulate the Tt enabled the design of an ELP that has a Tt between body temperature and 42 °C; this ELP showed enhanced accumulation in the tumor by thermally cycling between body temperature and 42 °C relative to a soluble ELP. In the third example, the thermal sensitivity of ELPs and precise control over the polymer sequence also enable construction of self-assembling block copolymers for hyperthermia-directed multivalent display. Thermal coacervation of ELP also enables formation of a long-lived radiotherapeutic depot following direct intratumoral administration, resulting in a one week tumor growth delay. In all cases, recombinant synthesis of ELP results in a monodisperse polymer with uniform properties, and these polymers are inherently biocompatible and biodegradable.

While the drug delivery strategies described above take advantage of the thermal responsiveness of ELPs, another promising future direction is to engineer these peptide polymers to respond to other intrinsic gradients that exist in vivo such as the small < 1 pH unit difference that exists between normal tissue and solid tumors [71, 72], and the larger pH difference between the cytoplasm and the endo-lysosomal compartments within cells [73]. In order to explore the feasibility of exploiting these intrinsic triggers of the ELP phase transition, we are currently synthesizing acidic, glutamic acid-rich ELPs that exhibit a decreasing Tt in response to low pH and basic, histidine-rich ELPs that display an increasing Tt in response to low pH. The dual thermal- and pH-sensitivity of these ELPs will be exploited in the design the next generation of “smart” drug delivery vehicles that are capable of undergoing a physical change in response to two orthogonal triggers: an intrinsic, chemical trigger such as the low extracellular pH found in hypoxic solid tumors or the low endosomal and lysosomal pH following cellular uptake, and an extrinsic, thermal trigger such as the application of mild hyperthermia.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Duncan R. Polymer conjugates as anticancer nanomedicines. Nature Reviews Cancer. 2006;6(9):688–701. doi: 10.1038/nrc1958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vasey PA, Kaye SB, Morrison R, Twelves C, Wilson P, Duncan R, Thomson AH, Murray LS, Hilditch TE, Murray T, Burtles S, Fraier D, Frigerio E, Cassidy J, I.I.I.C. Canc Res Campaign Phase Phase i clinical and pharmacokinetic study of pk1 n-(2-hydroxypropyl)methacrylamide copolymer doxorubicin : First member of a new class of chemotherapeutic agents - drug-polymer conjugates. Clinical Cancer Research. 1999;5(1):83–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chuang VTG, Kragh-Hansen U, Otagiri M. Pharmaceutical strategies utilizing recombinant human serum albumin. Pharmaceutical Research. 2002;19(5):569–577. doi: 10.1023/a:1015396825274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vandamme TF, Lenourry A, Charrueau C, Chaumeil J. The use of polysaccharides to target drugs to the colon. Carbohydrate Polymers. 2002;48(3):219–231. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Allen TM. Liposomes - opportunities in drug delivery. Drugs. 1997;54:8–14. doi: 10.2165/00003495-199700544-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kataoka K, Harada A, Nagasaki Y. Block copolymer micelles for drug delivery: Design, characterization and biological significance. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2001;47(1):113–31. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(00)00124-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Odonnell PB, McGinity JW. Preparation of microspheres by the solvent evaporation technique. Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews. 1997;28(1):25–42. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(97)00049-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yasuhiro Matsumura HM. A new concept for macromolecular therapeutics in cancer chemotherapy: Mechanism of tumoritropic accumulation of proteins and the antitumor agent smancs. Cancer Research. 1986;46:6387–6392. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Maeda H, Bharate GY, Daruwalla I. Polymeric drugs for efficient tumor-targeted drug delivery based on epr-effect. European Journal of Pharmaceutics and Biopharmaceutics. 2009;71:409–419. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpb.2008.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yuan F, Dellian M, Fukumura D, Leunig M, Berk DA, Torchilin VP, Jain RK. Vascular permeability in a human tumor xenograft: Molecular size dependence and cutoff size. Cancer Research. 1995;55:3752–3756. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Seymour LW, Miyamoto Y, Maeda H, Brereton M, Strohalm J, Ulbrich K, Duncan R. Influence of molecular-weight on passive tumor accumulation of a soluble macromolecular drug carrier. European Journal of Cancer. 1995;31A(5):766–770. doi: 10.1016/0959-8049(94)00514-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gabizon A, Catane R, Uziely B, Kaufman B, Safra T, Cohen R, Martin F, Huang A, Barenholz Y. Prolonged circulation time and enhanced accumulation in malignant exudates of doxorubicin encapsulated in polyethylene-glycol coated liposomes. Cancer Research. 1994;54(4):987–992. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Matsumura Y, Maeda H. A new concept for macromolecular therapeutics in cancer-chemotherapy - mechanism of tumoritropic accumulation of proteins and the antitumor agent smancs. Cancer Research. 1986;46(12):6387–6392. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Allen TM. Ligand-targeted therapeutics in anticancer therapy. Nature Reviews Cancer. 2002;2(10):750–763. doi: 10.1038/nrc903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chilkoti A, Dreher MR, Meyer DE, Raucher D. Targeted drug delivery by thermally responsive polymers. Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews. 2002;54(5):613–630. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(02)00041-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bidwell GL, Davis AN, Fokt I, Priebe W, Raucher D. A thermally targeted elastin-like polypeptide-doxorubicin conjugate overcomes drug resistance. Investigational New Drugs. 2007;25(4):313–326. doi: 10.1007/s10637-007-9053-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Minko T, Kopeckova P, Pozharov V, Kopecek J. Hpma copolymer bound adriamycin overcomes mdr1 gene encoded resistance in a human ovarian carcinoma cell line. Journal of Controlled Release. 1998;54(2):223–233. doi: 10.1016/s0168-3659(98)00009-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ryser HJP, Shen WC. Conjugation of methotrexate to poly(l-lysine) increases drug transport and overcomes drug-resistance in cultured-cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1978;75(8):3867–3870. doi: 10.1073/pnas.75.8.3867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gray WR, Sandberg LB, Foster JA. Molecular model for elastin structure and function. Nature. 1973;246(5434):461–6. doi: 10.1038/246461a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tatham AS, Shewry PR. Elastomeric proteins: Biological roles, structures and mechanisms. Trends Biochem Sci. 2000;25(11):567–71. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(00)01670-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Urry DW, Parker TM, Reid MC, Gowda DC. Biocompatibility of the bioelastic materials, poly(gvgvp) and its gamma-irradiation cross-linked matrix - summary of generic biological test-results. Journal of Bioactive and Compatible Polymers. 1991;6(3):263–282. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shamji MF, Betre H, Kraus VB, Chen J, Chilkoti A, Pichika R, Masuda K, Setton LA. Development and characterization of a fusion protein between thermally responsive elastin-like polypeptide and interleukin-1 receptor antagonist: Sustained release of a local antiinflammatory therapeutic. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56(11):3650–61. doi: 10.1002/art.22952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu WE, Dreher MR, Furgeson DY, Peixoto KV, Yuan H, Zalutsky MR, Chilkoti A. Tumor accumulation, degradation and pharmacokinetics of elastin-like polypeptides in nude mice. Journal of Controlled Release. 2006;116(2):170–178. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2006.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Meyer DE, Chilkoti A. Genetically encoded synthesis of protein-based polymers with precisely specified molecular weight and sequence by recursive directional ligation: Examples from the elastin-like polypeptide system. Biomacromolecules. 2002;3(2):357–367. doi: 10.1021/bm015630n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Meyer DE, Chilkoti A. Purification of recombinant proteins by fusion with thermally-responsive polypeptides. Nat Biotechnol. 1999;17(11):1112–5. doi: 10.1038/15100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Trabbic-Carlson K, Liu L, Kim B, Chilkoti A. Expression and purification of recombinant proteins from escherichia coli: Comparison of an elastin-like polypeptide fusion with an oligohistidine fusion. Protein Sci. 2004;13(12):3274–84. doi: 10.1110/ps.04931604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.MacKay JA, Chen M, McDaniel JR, Liu W, Simnick AJ, Chilkoti A. Self-assembling chimeric polypeptide-doxorubicin conjugate nanoparticles that abolish tumours after a single injection. Nat Mater. 2009;8(12):993–9. doi: 10.1038/nmat2569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Meyer DE, Shin BC, Kong GA, Dewhirst MW, Chilkoti A. Drug targeting using thermally responsive polymers and local hyperthermia. J Control Release. 2001;74(1-3):213–24. doi: 10.1016/s0168-3659(01)00319-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dreher MR, Liu W, Michelich CR, Dewhirst MW, Chilkoti A. Thermal cycling enhances the accumulation of a temperature-sensitive biopolymer in solid tumors. Cancer Res. 2007;67(9):4418–24. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-4444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dreher MR, Simnick AJ, Fischer K, Smith RJ, Patel A, Schmidt M, Chilkoti A. Temperature triggered self-assembly of polypeptides into multivalent spherical micelles. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2008;130(2):687–694. doi: 10.1021/ja0764862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liu W, Mackay JA, Dreher MR, Chen M, McDaniel JR, Simnick AJ, Callahan DJ, Zalutsky MR, Chilkoti A. Injectable intratumoral depot of thermally responsive polypeptide-radionuclide conjugates delays tumor progression in a mouse model. J Control Release. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2010.01.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Soppimath KS, Aminabhavi TM, Kulkarni AR, Rudzinski WE. Biodegradable polymeric nanoparticles as drug delivery devices. Journal of Controlled Release. 2001;70(1-2):1–20. doi: 10.1016/s0168-3659(00)00339-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ishida O, Maruyama K, Sasaki K, Iwatsuru M. Size-dependent extravasation and interstitial localization of polyethyleneglycol liposomes in solid tumor-bearing mice. International journal of pharmaceutics. 1999;190(1):49–56. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5173(99)00256-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kataoka K, Kwon GS, Yokoyama M, Okano T, Sakurai Y. Block-copolymer micelles as vehicles for drug delivery. Journal of Controlled Release. 1993;24(1-3):119–132. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Meyer DE, Kong GA, Dewhirst MW, Zalutsky MR, Chilkoti A. Targeting a genetically engineered elastin-like polypeptide to solid tumors by local hyperthermia. Cancer Res. 2001;61(4):1548–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Minotti G, Menna P, Salvatorelli E, Cairo G, Gianni L. Anthracyclines: Molecular advances and pharmacologic developments in antitumor activity and cardiotoxicity. Pharmacol. Rev. 2004;56(2):185–229. doi: 10.1124/pr.56.2.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Singal PK, Iliskovic N. Doxorubicin-induced cardiomyopathy. N. Engl. J. Med. 1998;339(13):900–905. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199809243391307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kopecek J, Kopeckova P, Minko T, Lu ZR. Hpma copolymer-anticancer drug conjugates: Design, activity, and mechanism of action. European Journal of Pharmaceutics and Biopharmaceutics. 2000;50(1):61–81. doi: 10.1016/s0939-6411(00)00075-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bae Y, Nishiyama N, Fukushima S, Koyama H, Yasuhiro M, Kataoka K. Preparation and biological characterization of polymeric micelle drug carriers with intracellular ph-triggered drug release property: Tumor permeability, controlled subcellular drug distribution, and enhanced in vivo antitumor efficacy. Bioconjugate Chem. 2005;16(1):122–130. doi: 10.1021/bc0498166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Greish K, Sawa T, Fang J, Akaike T, Maeda H. Sma-doxorubicin, a new polymeric micellar drug for effective targeting to solid tumours. Journal of Controlled Release. 2004;97(2):219–230. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2004.03.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kataoka K, Matsumoto T, Yokoyama M, Okano T, Sakurai Y, Fukushima S, Okamoto K, Kwon GS. Doxorubicin-loaded poly(ethylene glycol)-poly(beta-benzyl-l-aspartate) copolymer micelles: Their pharmaceutical characteristics and biological significance. Journal of Controlled Release. 2000;64(1-3):143–153. doi: 10.1016/s0168-3659(99)00133-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chytil P, Etrych T, Konak C, Sirova M, Mrkvan T, Rihova B, Ulbrich K. Properties of hpma copolymer-doxorubicin conjugates with ph-controlled activation: Effect of polymer chain modification. Journal of Controlled Release. 2006;115(1):26–36. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2006.06.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Furgeson DY, Dreher MR, Chilkoti A. Structural optimization of a “Smart” Doxorubicin-polypeptide conjugate for thermally targeted delivery to solid tumors. Journal of Controlled Release. 2006;110(2):362–369. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2005.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pechar M, Braunova A, Ulbrich K, Jelinkova M, Rihova B. Poly(ethylene glycol) - doxorubicin conjugates with ph-controlled activation. Journal of Bioactive and Compatible Polymers. 2005;20(4):319–341. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vetvicka D, Hruby M, Hovorka O, Etrych T, Vetrik M, Kovar L, Kovar M, Ulbrich K, Rihova B. Biological evaluation of polymeric micelles with covalently bound doxorubicin. Bioconjugate Chem. 2009;20(11):2090–2097. doi: 10.1021/bc900212k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gerweck LE, Seetharaman K. Cellular ph gradient in tumor versus normal tissue: Potential exploitation for the treatment of cancer. Cancer Research. 1996;56(6):1194–1198. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kong G, Braun RD, Dewhirst MW. Hyperthermia enables tumor-specific nanoparticle delivery: Effect of particle size. Cancer Research. 2000;60(16):4440–4445. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lopes de Menezes DE, Mayer LD. Pharmacokinetics of bcl-2 antisense oligonucleotide (g3139) combined with doxorubicin in scid mice bearing human breast cancer solid tumor xenografts. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2002;49(1):57–68. doi: 10.1007/s00280-001-0385-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dewhirst MW, Prosnitz L, Thrall D, Prescott D, Clegg S, Charles C, MacFall J, Rosner G, Samulski T, Gillette E, LaRue S. Hyperthermic treatment of malignant diseases: Current status and a view toward the future. Semin Oncol. 1997;24(6):616–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pisani LJ, Ross AB, Diederich CJ, Nau WH, Sommer FG, Glover GH, Butts K. Effects of spatial and temporal resolution for mr image-guided thermal ablation of prostate with transurethral ultrasound. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2005;22(1):109–18. doi: 10.1002/jmri.20339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Feyerabend T, Steeves R, Wiedemann GJ, Richter E, Robins HI. Rationale and clinical status of local hyperthermia, radiation, and chemotherapy in locally advanced malignancies. Anticancer Res. 1997;17(4B):2895–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Needham D, Dewhirst MW. The development and testing of a new temperature-sensitive drug delivery system for the treatment of solid tumors. Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews. 2001;53(3):285–305. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(01)00233-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Frenkel V. Ultrasound mediated delivery of drugs and genes to solid tumors. Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews. 2008;60(10):1193–1208. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2008.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wust P, Hildebrandt B, Sreenivasa G, Rau B, Gellermann J, Riess H, Felix R, Schlag PM. Hyperthermia in combined treatment of cancer. Lancet Oncology. 2002;3(8):487–497. doi: 10.1016/s1470-2045(02)00818-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Urry DW, Trapane TL, Prasad KU. Phase-structure transitions of the elastin polypentapeptide-water system within the framework of composition-temperature studies. Biopolymers. 1985;24(12):2345–56. doi: 10.1002/bip.360241212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Meyer DE, Chilkoti A. Quantification of the effects of chain length and concentration on the thermal behavior of elastin-like polypeptides. Biomacromolecules. 2004;5(3):846–51. doi: 10.1021/bm034215n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Algire GH. An adaptation of the transparent chamber technique to the mouse. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 1943;4:1–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Menger MD, Laschke MW, Vollmar B. Viewing the microcirculation through the window: Some twenty years experience with the hamster dorsal skinfold chamber. European Surgical Research. 2002;34(1-2):83–91. doi: 10.1159/000048893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Peer D, Karp JM, Hong S, Farokhzad OC, Margalit R, Langer R. Nanocarriers as an emerging platform for cancer therapy. Nature Nanotechnology. 2007;2:751–760. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2007.387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lu Y, Low PS. Folate-mediated delivery of macromolecular anticancer therapeutic agents. Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews. 2002;54(5):675–693. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(02)00042-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Torchilin VP. Targeted pharmaceutical nanocarriers for cancer therapy and imaging. The AAPS Journal. 2007;9(2):128–147. doi: 10.1208/aapsj0902015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Caplan MR, Rosca EV. Targeting drugs to combinations of receptors: A modeling analysis of potential specificity. Annals of Biomedical Engineering. 2005;33(8):1113–1124. doi: 10.1007/s10439-005-5779-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Mauriz JL, Gonzalez-Gallego J. Antiangiogenic drugs: Current knowledge and new approaches to cancer therapy. Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences. 2008;97(10):4129–4154. doi: 10.1002/jps.21286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Simnick AJ, Valencia CA, Liu R, Chilkoti A. Morphing low-affinity ligands into high-avidity nanoparticles by thermally triggered self-assembly of a genetically encoded polymer. ACS nano. 4(4):2217–27. doi: 10.1021/nn901732h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bier J, Benders P, Wenzel M, Bitter K. Kinetics of 57co-bleomycin in mice after intravenous, subcutaneous and intratumoral injection. Cancer. 1979;44(4):1194–1200. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197910)44:4<1194::aid-cncr2820440405>3.0.co;2-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Tomita T. Interstitial chemotherapy for brain tumors: A review. Journal of Neuro-Oncology. 1991;10(1):57–74. doi: 10.1007/BF00151247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wang Y, Hu JK, Krol A, Li Y-P, Li C-Y, Yuan F. Systemic dissemination of viral vectors during intratumoral injection. Molecular Cancer Therapy. 2003;2:1233–1242. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Celikoglu F, Celikoglu SI, York AM, Goldberg EP. Intratumoral administration of cisplatin through a broncoscope followed by irradiation for treatment of inoperable non-small cell obstructive lung cancer. Lung Cancer. 2006;51(2):225–236. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2005.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Nakase Y, Hagiwara A, Kin S, Fukuda K.-i., Ito T, Takagi T, Fujiyama J, Sakakura C, Otsuji E, Yamagishi H. Intratumoral administration of methotrexate bound to activated carbon particles: Antitumor effectiveness against human colon carcinoma xenografts and acute toxicity in mice. The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 2004;311:382–387. doi: 10.1124/jpet.104.069450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Chen S, Yu L, Jiang C, Zhao Y, Sun D, Li S, Liao G, Chen Y, Fu Q, Tao Q, Ye D, Hu P, Khawli LA, Taylor CR, Epstein AI, Ju DW. Pivotal study of iodine-131-labeled chimeric tumor necrosis treatment radioimmunotherapy in patients with advanced lung cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2005;23(7):1538–1547. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.06.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Cardone RA, Casavola V, Reshkin SJ. The role of disturbed ph dynamics and the na+/h+ exchanger in metastasis. Nature reviews. 2005;5(10):786–95. doi: 10.1038/nrc1713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Engin K, Leeper DB, Cater JR, Thistlethwaite AJ, Tupchong L, McFarlane JD. Extracellular ph distribution in human tumours. Int J Hyperthermia. 1995;11(2):211–6. doi: 10.3109/02656739509022457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.El-Sayed MEH, Hoffman AS, Stayton PS. Smart polymeric carriers for enhanced intracellular delivery of therapeutic macromolecules. Expert Opinion on Biological Therapy. 2005;5(1):23–32. doi: 10.1517/14712598.5.1.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]