Abstract

Objective

To analyze the relationship of legal status and employment conditions with health indicators in foreign-born and Spanish-born workers in Spain.

Methods

Cross-sectional study of 1,849 foreign-born and 509 Spanish-born workers (2008–2009, ITSAL Project). Considered employment conditions: permanent, temporary and no contract (foreign-born and Spanish-born); considered legal statuses: documented and undocumented (foreign-born). Joint relationships with self-rated health (SRH) and mental health (MH) were analyzed via logistical regression.

Results

When compared with male permanently contracted Spanish-born workers, worse health is seen in undocumented foreign-born, time in Spain ≤3 years (SRH aOR 2.68, 95% CI 1.09–6.56; MH aOR 2.26, 95% CI 1.15–4.42); in Spanish-born, temporary contracts (SRH aOR 2.40, 95% CI 1.04–5.53); and in foreign-born, temporary contracts, time in Spain >3 years (MH: aOR 1.96, 95% CI 1.13–3.38). In females, highest self-rated health risks are in foreign-born, temporary contracts (aOR 2.36, 95% CI 1.13–4.91) and without contracts, time in Spain >3 years (aOR 4.63, 95% CI 1.95–10.97).

Conclusions

Contract type is a health determinant in both foreign-born and Spanish-born workers. This study offers an uncommon exploration of undocumented migration and raises methodological issues to consider in future research.

Keywords: Emigration and immigration, Illegal migrants, Migrant workers, Employment, Contracts, Occupational health

Introduction

Migration is a growing global phenomenon with far from conclusively understood health effects. As trends continue to rise, the development of clear, certain explanations of migration-health mechanisms becomes increasingly urgent. This research demand is complicated, however, by methodological challenges inherent to studies of migrant populations in today’s society (Bloch 2007). Undocumented immigrants are not recorded in population databases, preventing the construction of a complete, accurate sampling frame. Legal status is a sensitive subject, as well, potentially leading to self-selection out of survey participation, skewing results and limiting the study of legal status effects on the interface between migration and health (Gushulak and MacPherson 2006). What is clear is that, regardless of methodological roadblocks, migration is an ever-present global phenomenon affecting the lives of too many to be ignored. Above all, the undocumented are extremely vulnerable to accidents, injuries, and psychosocial distress resulting from poor working conditions (Ahonen et al. 2009b; Akhavan et al. 2004; Lopez-Jacob et al. 2008; Simich et al. 2007) and marginal living conditions, associated with poverty, social exclusion, and discrimination (Agudelo-Suarez et al. 2009).

Although previous research on the healthy migrant effect explains a phenomenon of selective migration, migrants may still face potential health effects stemming from different situations than host populations, as well as unique economic and social factors in the labor market (Kandula et al. 2004). While the body of literature about migration and health in Spain is growing, studies about the health effects of working conditions are sparse. Moreover, it is necessary to research relevant occupational health determinants in immigrant populations in greater depth.

In addition to legal status, employment conditions are especially relevant to migration-health issues, as economic motivations to move are common. A review of the health effects of temporary employment shows increased risks of psychological morbidity and occupational injuries among temporary workers (Virtanen et al. 2005). Certain forms of temporary contracts have also been associated with negative health, varied by health outcome, sex, and social class, in another specific study of migrant populations in Spain (Borrell et al. 2008). While an understanding is emerging that work without a permanent job contract has negative health effects, it is far from conclusive, and remains to be further explored and refined in immigrant populations.

The ITSAL—Inmigración, Trabajo y Salud—Project (Garcia et al. 2009) is a collaboration between four Spanish universities and a trade union institute, looking at immigration, work and health. Set in Spain, the ITSAL Project takes advantage of the country’s recent immigration boom, with the foreign-born population increasing from 1% of the national population in 1996 to 12% in 2009 (Reher et al. 2008). The project’s large sub-sample of undocumented workers provides a rare opportunity to explore the largely unknown effects of legal status on health. The results from the project’s earlier qualitative phase establish precariousness of the immigrants’ situations, mainly due to work vulnerability, lack of rights and benefits, poverty and poor employment conditions. These factors have been linked with general health and mental health problems, and with increased occupational risk. Moreover, earlier ITSAL phases have highlighted the importance of identifying social determinants to help clarify the relationship between working conditions and health (Ahonen 2009; Porthé 2009).

The analyses presented here combine the better understood employment conditions with the largely untouchable legal status as conditions potentially significant to immigrant health. This novel approach allows us to observe the variation in health effects across a continuum of both legal status and employment conditions experienced by foreign-born workers in Spain. The objective of this study is to analyze this variation separately in males and females, gaining an additional perspective on the health effects of employment conditions, and making a first observation of the elusive relationship between legal status and health, with employment conditions in mind.

Methods

A cross-sectional study was conducted to examine the relationship between work and health in foreign-born and native-born workers in Spain.

Data collection

Following qualitative investigation in 2006 (focus groups and in-depth interviews with 158 foreign-born workers) (Garcia et al. 2009), a 74-item questionnaire was developed to collect data related to sociodemographics, the migration process, occupational and economic variables, employment conditions, working conditions, occupational risk prevention activities, participation in trade unions, physical and mental health, and overall evaluation of individuals’ experiences working in Spain (questionnaire available upon request). A first version of the questionnaire was tested in a pilot study of 35 foreign-born workers, measuring and improving language comprehension, time to completion, and internal consistency of the tool. The final version of the questionnaire was used with foreign-born and Spanish-born workers in this study between April 2008 and February 2009.

The sample of foreign-born workers (n = 2,434) consists of individuals from Morocco, Ecuador, Romania, and Colombia (four of the most prevalent countries of origin of immigrants in Spain), living in Barcelona, Huelva, Madrid or Valencia (four Spanish cities with high proportions of foreign-born residents). Inclusion criteria include a minimum of 1 year living in Spain; a minimum of 3 months work history in Spain (excluding work as an athlete, artist, graduate student, or business executive); not holding Spanish citizenship; no marriage to a native Spaniard; and adequate Spanish language abilities to participate in the interview. Quota sampling methodology was used, with quotas set by nationality, gender, and area of residence in Spain. Interviews were conducted with a 55.8% response rate. The sample of Spanish-born workers consists of individuals between 20 and 40 years, and therefore to increase comparability in the analyses, the foreign-born sample was restricted to workers under 40 (n = 1,849) for this study.

The sample of Spanish-born workers (n = 509) was built to resemble the foreign-born sample according to gender, age, and area of residence in Spain. Sampling was done in neighborhoods with at least 15% of the population foreign-born, in the same four cities used in the foreign-born sample. These interviews were conducted with a 55.0% response rate.

All selected individuals within the inclusion criteria were invited to participate in the study and given an informational letter explaining their rights and guaranteeing individual confidentiality. Participation was voluntary, with consent implied by completion of the survey. Surveys (average duration 30 min) were administered by professional interviewers in locations commonly frequented by immigrants (associations that ceded their space, cultural centers, meeting rooms in urban hotels, and participants’ workplaces and homes). The interviewers received specific training in the survey’s objectives, trust-building techniques, and cultural/linguistic barrier management strategies. The responsibility for data quality control was shared between the contracted fieldwork organization (verification of the questionnaires’ content, logistic items and codification) and the research institutions (process supervision).

Variable definitions

Two outcome variables were used separately to assess health status: self-rated health (How would you rate your current health status?) and mental health (General Health Questionnaire—12). Each was dichotomized. Self-rated health was classified as good (original responses: good or very good) or poor (original responses: fair, poor, or very poor). Mental health was measured with the 12-item version of the General Health Questionnaire GHQ-12 (Goldberg and Williams 1996). Responses were rated and summed, and individuals with a score of 3 or higher were classified with high probability of a psychiatric disorder (presence of poor mental health yes/no). Both health measures have been extensively used and validated in previous studies (Goldberg et al. 1997; Idler and Benyamini 1997; Makowska et al. 2002).

Our main explanatory variable, legal/contract situation, combined information about legal status and employment conditions. In this study, legal status was defined by permission to work. The questionnaire asked, “Do you have permission to work in Spain?” with affirmative responses classifying individuals as documented and negative responses classifying individuals as undocumented. For the majority of non-EU foreign-born individuals in Spain, permission to work requires permission to reside (exceptions include workers who come under cross-country agreements and seasonal agricultural workers, who were excluded from our sample). However, permission to reside generally also requires a job offer, except in family reunification and other refugee and humanitarian circumstances (Spain 2000). We decided to collect data on permission to work, rather than permission to reside, to increase participation and confidence in the validity of responses. Employment conditions were defined by type of contract (none, temporary, or permanent).

Legal/contract situation divided our sample into seven subgroups: Spanish-born, permanently contracted; Spanish-born, temporarily contracted; Spanish-born, non-contracted; foreign-born, documented, permanently contracted; foreign-born, documented, temporarily contracted; foreign-born, documented, non-contracted; and foreign-born undocumented.

Sex, age (under 30, 30–39 years), highest achieved level of education (primary education, secondary, university), and sector of economic activity (agriculture, industry/utilities, construction, commerce, hospitality, transport/communication, business/finance, public administration/education/social services or domestic), monthly income (in Euros ≤600, 601–1,200, 1,201–1,800, >1,800) were also included in the analysis.

Analysis

Analyses were conducted to assess the relationship between legal/contract situation and both self-rated health and mental health. The distribution of included variables was computed for each legal/contract subgroup. Logistical regression models were then constructed to measure the relationship of legal/contract situation with each of the health outcomes of interest. All analyses were conducted separately for men and women; first crudely, and then adjusted for age, education, sector of economic activity and income. In the case of foreign workers, analyses were stratified for the time in Spain (≤3 years, >3 years). This stratification was done to control for the healthy migrant effect and the process of integration in the host country. The results were recorded as odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals. All calculations were computed using SPSS 15.

Results

Sex, age, education, economic activity, monthly income, and time in Spain varied across legal/contract situations, as seen in Table 1. Foreign-born undocumented workers were the youngest group; Spanish-born non-contracted workers were the oldest. Proportions of individuals with at secondary and university education were highest in permanently contracted workers (foreign-born and Spanish-born), and lowest in non-permanently contracted foreign-born workers (documented, temporarily contracted; documented non-contracted; and undocumented).

Table 1.

Distribution of each legal/contract situation across socio-demographic variables (ITSAL Project, Spain 2008)

| Spanish-born | Foreign-born | Total n (%) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Permanent contract n (%) | Temporary contract n (%) | No contract n (%) | Documented, permanent contract n (%) | Documented, temporary contract n (%) | Documented, no contract n (%) | Undocumented n (%) | ||

| Sex | ||||||||

| Male | 123 (51.0) | 112 (54.1) | 27 (44.3) | 275 (56.1) | 474 (62.7) | 91 (55.2) | 248 (56.6) | 1,350 (57.3) |

| Female | 118 (49.0) | 95 (45.9) | 34 (55.7) | 215 (43.9) | 282 (37.3) | 74 (44.8) | 190 (43.4) | 1,008 (42.7) |

| Age | ||||||||

| Under 30 | 89 (36.9) | 113 (54.6) | 19 (31.1) | 224 (45.7) | 370 (48.9) | 83 (50.3) | 287 (65.5) | 1,185 (50.3) |

| 30–39 | 152 (63.1) | 94 (45.4) | 42 (68.9) | 266 (54.3) | 386 (51.1) | 82 (49.7) | 151 (34.5) | 1,173 (49.7) |

| Education | ||||||||

| Primary, at most | 41 (17.0) | 52 (25.1) | 17 (27.9) | 92 (18.8) | 264 (34.9) | 57 (34.5) | 142 (32.4) | 665 (28.2) |

| Secondary | 109 (45.2) | 103 (49.8) | 28 (45.9) | 277 (56.5) | 389 (51.5) | 80 (48.5) | 229 (52.3) | 1,215 (51.5) |

| University | 91 (37.8) | 52 (25.1) | 16 (26.2) | 121 (24.7) | 101 (13.4) | 28 (17.0) | 65 (14.8) | 474 (20.1) |

| Economic sectors | ||||||||

| Agriculture | 3 (1.2) | 10 (4.8) | 0 | 10 (2.0) | 120 (15.9) | 20 (12.1) | 67 (15.3) | 230 (9.8) |

| Industry/utilities | 57 (23.7) | 23 (11.1) | 2 (3.3) | 53 (10.8) | 68 (9.0) | 6 (3.6) | 19 (4.3) | 228 (9.7) |

| Construction | 13 (5.4) | 35 (16.9) | 3 (4.9) | 95 (19.4) | 220 (29.1) | 30 (18.2) | 90 (20.5) | 486 (20.6) |

| Commerce | 48 (19.9) | 30 (14.5) | 18 (29.5) | 83 (16.9) | 79 (10.4) | 25 (15.2) | 29 (6.6) | 312 (13.2) |

| Hospitality | 15 (6.2) | 24 (11.6) | 13 (21.3) | 88 (18.0) | 98 (13.0) | 23 (13.9) | 94 (21.5) | 355 (15.1) |

| Transport/communication | 18 (7.5) | 13 (6.3) | 0 0 | 47 (9.6) | 41 (5.4) | 9 (5.5) | 12 (2.7) | 140 (5.9) |

| Business/finance | 42 (17.4) | 28 (13.5) | 10 (16.4) | 31 (6.3) | 46 (6.1) | 7 (4.2) | 22 (5.0) | 186 (7.9) |

| Public Admin./Educ/Social | 45 (18.7) | 44 (21.3) | 10 (16.4) | 50 (10.2) | 38 (5.0) | 6 (3.6) | 14 (3.2) | 207 (8.8) |

| Domestic personnel | 0 | 0 | 5 (8.2) | 32 (6.5) | 46 (6.1) | 39 (23.6) | 90 (20.5) | 212 (9.0) |

| Monthly income (Euros) | ||||||||

| ≤600 | 12 (5.0) | 32 (15.5) | 11 (18.0) | 28 (5.7) | 77 (10.2) | 37 (22.4) | 135 (30.8) | 332 (14.1) |

| 601–1,200 | 95 (39.4) | 111 (53.6) | 24 (39.3) | 318 (64.9) | 541 (71.6) | 96 (58.2) | 277 (63.2) | 1,462 (62.0) |

| 1,201–1,800 | 103 (42.7) | 47 (22.7) | 16 (26.2) | 116 (23.7) | 127 (16.8) | 19 (11.5) | 26 (5.9) | 454 (19.3) |

| >1,800 | 29 (12.0) | 15 (7.2) | 7 (11.5) | 27 (5.5) | 8 (1.1) | 13 (7.9) | 0 | 99 (4.2) |

| Time in Spain (for foreign-born, in years) | ||||||||

| ≤3 | – | – | – | 88 (18.0) | 137 (18.1) | 44 (26.7) | 270 (61.8) | 539 (29.2) |

| >3 | – | – | – | 402 (82.0) | 619 (81.9) | 121 (73.3) | 167 (38.2) | 1,309 (70.8) |

| Total | 241 (100) | 207 (100) | 61 (100) | 490 (100) | 756 (100) | 165 (100) | 438 (100) | 2,358 (100) |

Variation across sectors of economic activity is also seen in the table. As expected, the foreign-born workers in our sample are concentrated in agricultural and construction work, and our sample includes few Spanish-born workers in these sectors. In addition as expected, in our study, foreign-born workers were commonly temporarily contracted. Workers with permanent contracts had the highest salaries, and undocumented foreign-born workers had the lowest.

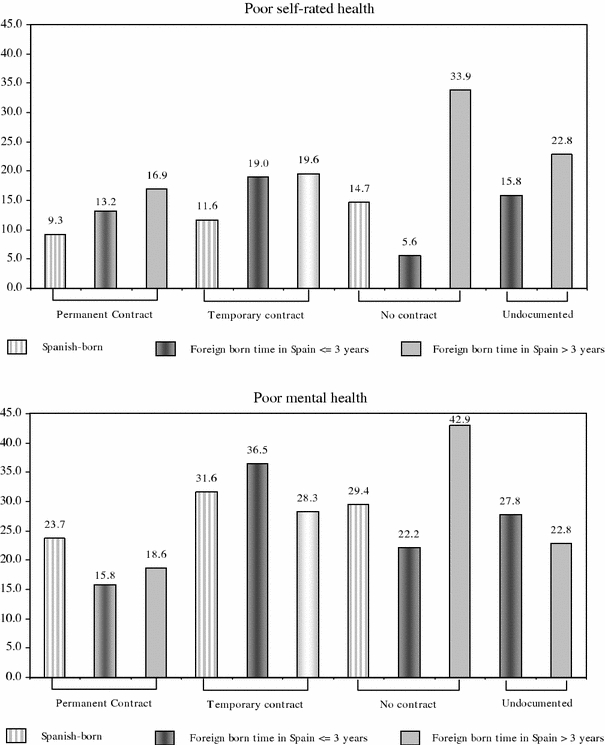

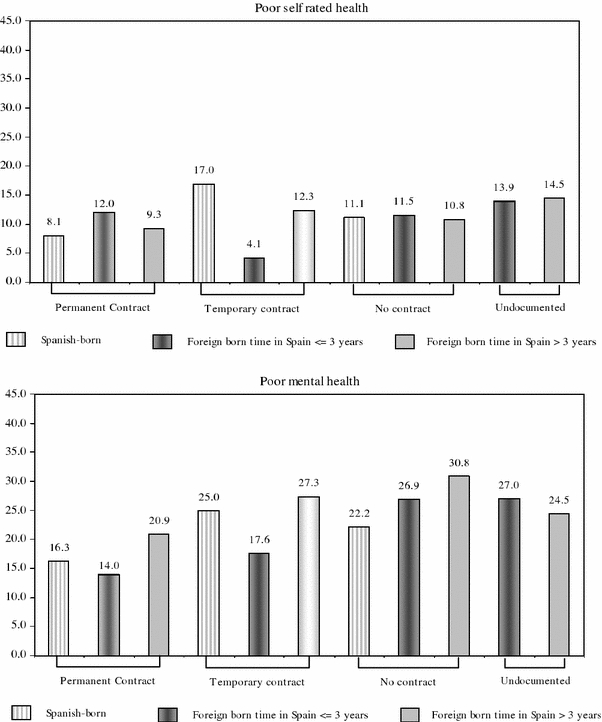

As seen in Figs. 1 and 2, the highest prevalence of both poor self-rated health (33.9%) and poor mental health (42.9%) were observed in foreign-born documented females without contracts who had lived in Spain for more than 3 years. A high prevalence of poor mental health (30.8%) was also observed in foreign-born males without contracts who had lived in Spain for more than 3 years. In recent immigrants (time in Spain ≤3 years), an elevated prevalence of both negative health outcomes are seen in female foreign-born workers with temporary contracts (poor self-rated health and poor mental health of 19 and 36.5%, respectively).

Fig. 1.

Prevalence of poor health outcomes by legal status/contract type in Spanish- and foreign-born workers (females)

Fig. 2.

Prevalence of poor health outcomes by legal status/contract type in Spanish- and foreign-born workers (males)

Tables 2 and 3 present the results of crude and adjusted analyses stratified by sex. Among females (Table 2), the highest risks of poor self-rated health were observed in foreign-born workers (time in Spain >3 years) without contracts (aOR 4.63, 95% CI 1.95–10.97) and with temporary contracts (aOR 2.36 CI 95% 1.13–4.91). In addition, interest with respect to self-rated health, we observed a gradient of risk by legal/contract situation from Spanish-born workers with contracts at the lowest risk to foreign-born workers without contracts at the highest (excluding recent immigrants without contracts). Significant differences in mental health were not achieved. However, the self-rated health of recent foreign-born workers without contracts and the mental health of foreign-born females with permanent contracts or no contracts tended to be better than that of Spanish-born females (although no statistical significance was achieved).

Table 2.

Comparison between legal status/contract type and two health outcomes of interest in females (ITSAL Project, Spain 2008)

| Legal/contract situation | Poor self-rated health | Poor mental health | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| cOR (95%CI) | aORa (95% CI) | cOR (95% CI) | aORa (95%CI) | |

| Spanish-born | ||||

| Permanent contract | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Temporary contract | 1.27 (0.53–3.08) | 1.18 (0.47–2.97) | 1.48 (0.81–2.72) | 1.20 (0.63–2.27) |

| No contract | 1.68 (0.54–5.21) | 1.32 (0.41–4.27) | 1.34 (0.57–3.14) | 1.11 (0.50–2.48) |

| Foreign-born, documented (time in Spain ≤3 years) | ||||

| Permanent contract | 1.47 (0.48–4.55) | 1.55 (0.49–4.85) | 0.60 (0.23–1.59) | 0.61 (0.29–1.27) |

| Temporary contract | 2.29 (0.95–5.54) | 2.06 (0.81–5.22) | 1.85 (0.95–3.60) | 1.46 (0.72–2.94) |

| No contract | 0.57 (0.69–4.72) | 0.53 (0.62–4.59) | 0.92 (0.28–3.02) | 0.71 (0.20–2.50) |

| Foreign-born, undocumented (time in Spain >3 years) | 1.82 (084–3.96) | 1.32 (0.57–3.01) | 1.24 (0.70–2.19) | 1.05 (0.56–1.98) |

| Foreign-born, documented (rest) | ||||

| Permanent contract | 1.99 (0.95–4.14) | 1.81 (0.85–3.84) | 0.74 (0.42–1.30) | 0.59 (0.32–1.07) |

| Temporary contract | 2.38 (1.18–4.81) | 2.36 (1.13–4.91) | 1.27 (0.76–2.13) | 0.99 (0.57–1.71) |

| No contract | 5.00 (2.18–11.47) | 4.63 (1.95–10.97) | 2.41 (1.22–4.75) | 1.93 (0.95–3.92) |

| Foreign-born, undocumented (rest) | 2.81 (1.20–6.90) | 2.53 (0.98–6.53) | 0.95 (0.45–2.01) | 0.73 (0.32–1.66) |

aAdjusted for age and education

Table 3.

Comparison between legal status/type of contract and two health outcomes of interest in males (ITSAL Project, Spain 2008)

| Legal/contract situation | Poor self-rated health | Poor mental health | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| cOR (95% CI) | aORa (95% CI) | cOR (95% CI) | aORa (95% CI) | |

| Spanish-born | ||||

| Permanent contract | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Temporary contract | 2.31 (1.02–5.21) | 2.40 (1.04–5.53) | 1.72 (0.90–3.26) | 1.53 (0.78–2.97) |

| No contract | 1.41 (0.36–5.52) | 1.24 (0.31–4.95) | 1.47 (0.53–4.11) | 1.62 (0.63–4.15) |

| Foreign-born, documented (time in Spain ≤3 years) | ||||

| Permanent contract | 1.54 (0.53–4.49) | 1.54 (0.53–4.56) | 0.84 (0.33-2.13) | 0.55 (0.28–1.08) |

| Temporary contract | 0.48 (0.13–1.79) | 0.55 (0.14–2.19) | 1.10 (0.51–2.36) | 1.09 (0.49–2.43) |

| No contract | 1.47 (0.38–5.78) | 1.36 (0.32–5.77) | 1.90 (0.71–5.11) | 2.05 (0.75–5.83) |

| Foreign-born, undocumented (time in Spain >3 years) | 1.82 (0.81–4.08) | 2.68 (1.09–6.56) | 1.91 (1.04–3.51) | 2.26 (1.15–4.42) |

| Foreign-born, documented (rest) | ||||

| Permanent contract | 1.16 (0.53–2.56) | 1.10 (0.50–2.44) | 1.36 (0.76–2.42) | 1.32 (0.74–2.35) |

| Temporary contract | 1.58 (0.77–3.22) | 1.80 (0.86–3.78) | 1.94 (1.13–3.48) | 1.96 (1.13-3.38) |

| No contract | 1.36 (0.49–3.79) | 1.15 (0.40–3.30) | 2.29 (1.12–4.66) | 2.07 (0.99–4.34) |

| Foreign-born, undocumented (rest) | 1.92 (0.83–4.44) | 2.06 (0.84-5.10) | 1.68 (0.88–3.20) | 1.49 (0.74–3.00) |

aAdjusted for age and education

In males (Table 3), undocumented foreign-born workers who lived in Spain ≤ 3 years (aOR 2.26, CI 95% 1.15–4.42) and foreign-born workers who lived >3 years and worked with temporary contracts (aOR 1.96, 95% CI 1.13–3.38) experienced the highest risk of mental health problems, relative to their Spanish-born permanently contracted counterparts. With respect to poor self-rated health, undocumented foreign-born workers who lived in Spain ≤ 3 years (aOR 2.68, CI 95% 1.09–6.56) and Spanish-born temporarily contracted workers (aOR 2.40, 95% CI 1.04–5.56) were at the highest risk. Documented foreign-born workers with temporary contracts and without contracts, as well as other undocumented foreign-born workers, experienced poor health outcomes, although they failed to reach statistical significance.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this study was the first to analyze the relationship between legal status, employment conditions, and immigrants’ health, providing an unprecedented look at the experiences of undocumented workers. In the findings presented, we see trends that worker health is more associated with employment conditions than legal status. This is reflected in the frequencies of both poor self-rated health and mental health across the seven legal/contract situation categories, in the odds ratio of mental health problems (male undocumented foreign-born workers, time in Spain ≤3 years; and male documented foreign-born workers with temporary contracts, time in Spain >3 years), and in the odds ratios of poor self-rated health (male Spanish-born workers with temporary contracts; male undocumented foreign-born workers, time in Spain <3 years; and female documented foreign-born workers, time in Spain >3 years, with temporary contracts or without contracts).

The observed association between employment conditions and health is supported by a recent review of relevant evidence (Benach et al. 2007), which highlighted the prevalence and health consequences of unfair and informal employment. Another recent study in Spain (Borrell et al. 2008) examined the influence of migration on health, and the role of employment conditions, along with social class and other factors. The authors found that migration affected self-rated health in both males and females, even after controlling for social class. Our findings regarding the effects of employment conditions on health agree with this existing literature. The less expected outcome—the relative importance of employment conditions over legal status—reemphasizes the effects of flexible employment in an already vulnerable population. Additional logistic regression models were constructed to compare Spanish-born and foreign-born workers with the same contract types and no statistically significant differences emerged between the two populations (data not shown).

Interestingly, we also observed variation in legal/contract situation’s effects by health measure between genders. In males, the 12-item mental health indicator was more associated with legal/contract situation than was the 1-item self-rated health measure. In females, the opposite was true, with self-rated health more sensitive than mental health to legal/contract situation. Similar differences have been observed in health outcome sensitivity to various factors among men and women in previous studies in Spain (Borrell et al. 2008; Rodriguez Alvarez et al. 2008). However, it is also important to study the influence of other potentially related variables, such as time since migration, working conditions (as they vary across social class and economic activity sectors), and perceived discrimination. Future research would be well guided to explore the health effects of these factors, as well as the potential effects of changes in individual immigrants’ social class between the origin and host societies.

The analyses yield surprising results regarding the relative health status of undocumented migrants, especially in females and foreign-born workers who have lived in Spain longer. These quantitative findings counter those of the earlier associated qualitative study, as well as those of other qualitative studies (Ahonen et al. 2009b; Simich et al. 2007). Although we cannot conclusively explain these differences, one potential explanation involves a possible relationship between legal status and time since migration. Immigrants who enter a host country undocumented and transition to a documented status have a longer history of cumulative precarious experiences than do more recent still-undocumented migrants. The change in documentation status may improve their situation, but they are still in vulnerable positions, and may retroactively be feeling the effects of their previous experiences as undocumented migrants. It is also conceivable that the transition to a more stable documented status acts as a catalyst for the expression of the effects of their previous more precarious situations.

All findings presented here should be interpreted with consideration of the study design constraints. As previously noted, migration research presents a variety of methodological issues, and this study is not without limitations. First, legal status is a sensitive issue for foreign-born subjects, with the potential for a perceived risk of legal consequences and/or deportation. To reduce the potential non-response bias and/or false responses, we chose to define legal status as permission to work rather than permission to reside. As this introduces the issue of measures of legal status, it is noted that findings presented here relate to undocumented workers; the degree to which undocumented worker and undocumented resident populations overlap, as well as a comparison and contrast of health effects between the two groups, requires future research. The time in Spain stratified analysis adds a dimension to the documented and undocumented overall situation. Time in Spain is considered to control for the healthy migrant, establishing differences between recent immigrant workers and the rest of the immigrants. However, sample size limitations prevent us from reaching reasonable statistical power, and it still insufficiently corrects for the “healthy immigrant effect” (which takes more than 3 years to disappear). Further analyses highlighting this situation and carried out in different immigrant groups would help in clarifying this situation.

Second, our sampling methods may compromise the external validity of the findings. The data for this study were collected under quota sampling methodology. The hidden nature of immigrant populations, especially the undocumented subgroup, has prevented a complete accurate description of the population of interest, prohibiting representative random sampling. Quota sampling offers a means to analyze across key demographic variables to try to get a meaningful look at heath of undocumented foreign-born populations (Bloch 2007). However, the potential effects on the ability to extrapolate findings to a larger population should be noted. In addition, it is important to take sample size limitations into account. A larger sample size would improve our statistical power. Nevertheless, characteristics of the immigrant population may be sufficiently represented by the included participants, given the nature of the research and the selected explanatory variables.

Finally, the cross-sectional nature of the data reduces the ability to assess causality in the observed relationships. We cannot be sure if working without contracts negatively affects workers’ health or if poor health status somehow acts as a limiting factor in attaining a job contract. The literature surrounding the healthy immigrant effect, however, supports health changes with time in the host country (Newbold 2005), boosting our confidence of the relationship’s direction and the conclusions drawn from our findings.

Accepting the above limitations, this study adds an examination of a large sample of undocumented immigrants to the existing literature on migration and health. We introduce a new combined analysis of employment conditions together with legal status to assess factors relevant to immigrants’ health. While the concrete findings should be interpreted considering the afore-mentioned limitations, we do get a glimpse into the growing global phenomenon of undocumented migration, about which much remains undiscovered. Although our population of interest’s hidden nature necessitated our deviation from ‘gold standard’ sampling methodology, the extent to which our findings agree with those of the preceding qualitative study (Ahonen et al. 2009a) increases our confidence in our current results. In both ITSAL phases, the importance of employment conditions, specifically contracts, emerged from the analyses. In the qualitative study, legal status also stood out as a factor increasing worker vulnerability and exploitation, while in this quantitative phase, legal status is observed as a less influential factor to health. An exploration of the assessment of legal status, and its effects on employment conditions and health outcomes has begun here, and future investigation would be well guided to continue to expand upon it towards more absolute understanding.

It should also be noted that this study was conducted at the end of an economic cycle with high rates of employment. It will be interesting to see how the situation changes as the upcoming economic dynamics impact a job market that already excludes many foreign-born workers, with 28.4% unemployment, as compared to 17.4% in Spanish-born workers (Spanish National Institute of Statistics, INE 2008).

This study presents an attempt to handle the methodological limitations inherent to migration research, and serves to aid the development of migration research methodology. Methodology developed from these experiences will potentially produce more generalizable findings via representative samples and inclusion of other representative collectives in Spain. Future research would be well guided to continue to explore the relationship between legal status, employment conditions, and health in immigrant workers. Other possible factors to consider include specific contract-related factors, such as duration, oral versus written nature, and the qualitative meaning of contract types in various economic sectors. This research can also be more rigorously compared with the existing knowledge of the effects of employment conditions on health (in general populations) to distill immigration-related health changes, and to help guide societal development, accommodating immigrants’ needs and protecting the rights and health of all people.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all participants in the study for sharing their time and experiences. The study was funded partially by Fondo de Investigaciones Sanitarias [Spanish Fund for Health Research] grant numbers FIS PI050497, PI052334, PI061701. Emily Sousa was funded by a grant from the Center for Research on Occupational Health at Universitat Pompeu Fabra.

Conflict of interest statement

None.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Footnotes

This paper belongs to the special issue “Health of ethnic minorities in Europe”.

References

- Agudelo-Suarez A, et al. Discrimination, work and health in immigrant populations in Spain. Soc Sci Med. 2009;68:1866–1874. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.02.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahonen EQ (2009) Immigrants, work and health: a qualitative study. Dissertation, University Pompeu Fabra

- Ahonen EQ, et al. Invisible work, unseen hazards: the health of women immigrant household service workers in Spain. Am J Ind Med. 2009;53:405–416. doi: 10.1002/ajim.20710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahonen EQ, et al. A qualitative study about immigrant workers’ perceptions of their working conditions in Spain. J Epidemiol Commun Health. 2009;63:936–942. doi: 10.1136/jech.2008.077016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akhavan S, et al. Health in relation to unemployment and sick leave among immigrants in Sweden from a gender perspective. J Immigr Health. 2004;6:103–118. doi: 10.1023/B:JOIH.0000030226.59785.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benach J, Muntaner C, Santana V (2007) Employment condition knowledge network (EMCOMET). Employment condition and health inequalities. Final Report to the WHO Commission on Social Determinants of Health

- Bloch A. Methodological challenges for national and multi-sited comparative survey research. J Refug Stud. 2007;20:230–247. doi: 10.1093/jrs/fem002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Borrell C, et al. Immigration and self-reported health status by social class and gender: the importance of material deprivation, work organisation and household labour. J Epidemiol Commun Health. 2008;62:e7. doi: 10.1136/jech.2006.055269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia AM, et al. Occupational health of immigrant workers in Spain [ITSAL Project]: key informants survey. Gac Sanit. 2009;23:91–97. doi: 10.1016/j.gaceta.2008.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg D, Williams P. General health questionnaire 12: user guide to the distinct versions. Spain: Mason; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg DP, et al. The validity of two versions of the GHQ in the WHO study of mental illness in general health care. Psychol Med. 1997;27:191–197. doi: 10.1017/S0033291796004242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gushulak BD, MacPherson DW. The basic principles of migration health: population mobility and gaps in disease prevalence. Emerg Themes Epidemiol. 2006;3:3. doi: 10.1186/1742-7622-3-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Idler EL, Benyamini Y. Self-rated health and mortality: a review of twenty-seven community studies. J Health Soc Behav. 1997;38:21–37. doi: 10.2307/2955359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kandula NR, Kersey M, Lurie N. Assuring the health of immigrants: what the leading health indicators tell us. Annu Rev Public Health. 2004;25:357–376. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.25.101802.123107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Jacob MJ, et al. Occupational injury in foreign workers by economic activity and autonomous community (Spain 2005) Rev Esp Salud Publica. 2008;82:179–187. doi: 10.1590/S1135-57272008000200004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makowska Z, et al. The validity of general health questionnaires, GHQ-12 and GHQ-28, in mental health studies of working people. Int J Occup Med Environ Health. 2002;15:353–362. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newbold KB. Self-rated health within the Canadian immigrant population: risk and the healthy immigrant effect. Soc Sci Med. 2005;60:1359–1370. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.06.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porthé V (2009) Precarious employment in immigrants in Spain and its relationship with health: a qualitative approximation. Dissertation, Universitat Pompeu Fabra

- Reher D et al (2008) Immigrant National Survey Report (ENI-2007)

- Rodriguez Alvarez E, et al. Sociodemographic variables and lifestyle as predictors of self-perceived health in immigrants in the Basque Country [Spain] Gac Sanit. 2008;22:404–412. doi: 10.1157/13126920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simich L, Wu F, Nerad S. Status and health security: an exploratory study of irregular immigrants in Toronto. Can J Public Health. 2007;98:369–373. doi: 10.1007/BF03405421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spain (2000) Ley Orgánica 4/2000, de 11 de enero, sobre derechos y libertades de los extranjeros en España y su integración social

- Spanish National Institute of Statistics—INE—Survey of the Active Population (EPA, 2008—4th Quarter) http://www.ine.es/

- Virtanen M, et al. Temporary employment and health: a review. Int J Epidemiol. 2005;34:610–622. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyi024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]