Abstract

Chronic oral anticoagulant treatment is obligatory in patients (class I) with mechanical heart valves and in patients with atrial fibrillation with CHADS2 score >1. When these patients undergo percutaneous coronary intervention with placement of a stent, there is also an indication for treatment with aspirin and clopidogrel. Unfortunately, triple therapy is known to increase the bleeding risk. For this group of patients, the bottom line is to find the ideal therapy in patients with indications for both chronic anticoagulation therapy and percutaneous intervention to prevent thromboembolic complications such as stent thrombosis without increasing the risk of bleeding. (Neth Heart J 2010;18:444–50.)

Keywords: Atrial Fibrillation, Triple Therapy, Dual Antiplatelet Therapy, Percutaneous Coronary Intervention, Mechanical Valves, Oral Anticoagulation

Chronic oral anticoagulant treatment is necessary in patients with mechanical heart valves and in patients with atrial fibrillation and CHADS 2 score >1, with deep venous thrombosis and pulmonary embolism.1,2 Many of these patients also have ischaemic heart disease. When these patients have to undergo percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) with stenting, there is also an indication for treatment with aspirin and clopidogrel.3 The number of these patients keeps on increasing due to a population that is getting older while life expectancy is increasing. However, triple therapy is known to increase the risk of bleeding complications.1,4,5 We also know that dual antiplatelet treatment and oral anticoagulant treatment are each associated with a nearly 15% risk of major or minor bleeding per year.6 It is still unknown what the best antithrombotic treatment is, when considering both thrombotic (e.g. stent thrombosis) and bleeding complications. Unfortunately, no prospective (randomised) data are available to solve this issue.

Rationale

Guidelines

The ACC/AHA/ESC 2006 guidelines for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation briefly address this issue: ‘Following PCI in patients with AF, there is a class IIb indication for the use of low-dose aspirin (less than 100 mg/day) and/or clopidogrel (75 mg/day) concurrent with anticoagulation use. This strategy has not been thoroughly evaluated and is associated with an increased risk of bleeding (Level of Evidence C)’. This guideline was established based on expert opinion and not on prospective randomised trials.1 In 2008 a detail was added: ‘In patients requiring warfarin, clopidogrel and aspirin therapy, an INR of 2.0 to 2.5 is recommended with low-dose aspirin (75 mg to 81 mg) and a 75 mg dose of clopidogrel’ (class IC).7 The 2008 ESC STEMI guidelines state the following: ‘In some patients, there is an indication for dual antiplatelet therapy and oral anticoagulation (e.g. stent placement and atrial fibrillation). In the absence of prospective randomised studies, no firm recommendations can be given. Triple therapy seems to have an acceptable risk-benefit ratio provided clopidogrel co-therapy is kept short and the bleeding risk is low.’ They also state that the combination of oral anticoagulants plus a short course of clopidogrel can be an alternative in patients with a higher risk of bleeding and that it is very important to avoid drug-eluting stents in patients who need oral anticoagulation.8

Facts

The challenge remains to find an adequate therapy for patients with both an indication for chronic oral anticoagulant use and for stent implantation. Four combinations are theoretically possible. First, the combined therapy of clopidogrel and aspirin proved unsafe because of an increased number of thromboembolic complications such as stroke.6,9,10 A second combination of oral anticoagulation therapy and aspirin is also unsafe because of a higher incidence of myocardial infarction and stent thrombosis.4,11,12 Because of this lack of effectiveness, it is recommended that the combination of oral anticoagulants and aspirin should not be prescribed.4,11-13 Clopidogrel, in combination with oral anticoagulant therapy, seems to be a promising option.13-15 Regarding the combination of oral anticoagulants and clopidogrel, there is insufficient evidence but further investigation is pending.13,16,17 This combination has a theoretical advantage that there are no local erosive effects of aspirin on the stomach and therefore the gastrointestinal bleeding risk should be lower. In the largest retrospective study so far, omitting aspirin did not lead to an excess of stroke, myocardial infarction or stent thrombosis.4,18 A possible pitfall is the fact that both clopidogrel and coumarin derivates such as acenocoumarol are metabolised by the hepatic cytochrome P450 system. Sibbing et al. showed that phenprocoumon significantly attenuates the antiplatelet effect of clopidogrel in an in vitro setting.19 The question remains as to whether this possible drug-drug interaction is also clinically important. Then there is the possibility of triple therapy. As expected, most studies report a higher bleeding risk.5,10,20-22 The combined number of minor and major bleeds in triple therapy patients varies up to 27.5%.5,10,13,23 Arguments in favour of triple therapy are low rates of stroke, myocardial infarction and stent thrombosis.14 Besides triple therapy itself other factors may be responsible for bleeding complications such as access site problems, the use of glycoprotein IIb/IIIa (GP IIb/IIIa) inhibitors, and excess use of peri-procedural heparins or low-molecular-weight heparins (LMWH).14 Of course, a history of intracranial bleeding is an absolute contraindication for triple therapy.14 In patients using triple therapy, the absolute bleeding risk can be minimised by using a radial approach, using bare metal stents (and thereby limiting the duration of clopidogrel therapy to a minimum of one month), using proton pomp inhibitors to limit bleeding of the gastrointestinal tract and avoiding the use of GP IIb/IIIa inhibitors.14 On the other hand, the safety of triple therapy has never been proven in a randomised trial.15 Second, the patients with an indication for chronic anticoagulant therapy are the ‘high-risk patients’ with many comorbidities. Adding dual antiplatelet treatment to the regimen of this vulnerable patient population already receiving oral anticoagulation for stroke prevention can increase the relative risk of life-threatening bleeds around tenfold.9 A common problem seems to be the underreporting of bleeding incidence. The current consensus was validated on the combination of 12 studies in which incidence of major bleeding was poorly reported.13 Therefore, triple therapy could be more dangerous than we think. A last argument is that this population largely consists of older people, many of them octogenarians. But, as we know, octogenarians are excluded from most studies. So guidelines/consensus reports cannot always apply to them. Many authors report a high rate of cardiac events in the oral anticoagulant group but this seems to be a reflection of a higher prevalence of high-risk features (diabetes, previous myocardial infarction, stroke, heart failure) at baseline.4,10,13,15

Patients in whom oral anticoagulants are contraindicated

In atrial fibrillation patients with a high stroke risk for whom vitamin K-antagonist therapy was unsuitable, the combination of clopidogrel and aspirin is known to reduce the risk of stroke while increasing bleeding risk.24 When these patients undergo PCI, logically the combination clopidogrel and aspirin should be continued.

Consensus

A consensus document on this topic was recently published13 in which it was recommended to treat patients with atrial fibrillation at intermediate or high risk undergoing coronary stenting with triple therapy, accepting the increased risk of major bleeding.13 This consensus was based on the combination of ten retrospective studies and two prospective registries.9,13 Lip, Zinn and Schomig also presented a pragmatic approach that is broadly similar to the Rubboli consensus.9,13,23,25 Triple therapy is usually advised, as short as possible until endothelialisation of the stent is complete and then clopidogrel is discontinued.9,13,23,25 In case of triple therapy treatment, it is advised to lower the target INR to 2.5 to 3.0 for mechanical heart valves and to 2.0 to 2.5 for other indications.23 All these recommendations take into account stroke risk, bleeding risk, the context of acute or elective stenting and the use of bare metal stents or drug-eluting stents. In every patient, a balance should be sought between bleeding and possible thromboembolic complications. The higher the patient’s bleeding risk, the more measures should be taken to avoid bleeding (radial approach, bare metal stent, no GP IIb/IIIa inhibitors, no peri-procedural bridging with low-molecular-weight heparins, use of proton pomp inhibitors).14 But the optimal treatment is currently undefined and therefore prospective randomised trials are needed and awaited.13,23

Clinical importance of bleeding after PCI

Why is reducing bleeding risk so important? Several studies have shown a link between major bleeding and a higher mortality rate.18,26-28 Relevant factors are the choice of vascular access (radial vs. femoral) and the choice of antithrombotic regimen.22 The importance of bleeding as an adverse event is also emphasised by the fact that bleeding is becoming part of a primary endpoint in recent PCI trials.17,26 But there is still a long way to go because different trials often use a different definition of major bleeding. The two best known are the Thrombolysis In Myocardial Infarction (TIMI) and GUSTO bleeding definitions (table 1).29,30 Rao et al. showed that the GUSTO bleeding score is the best predictor for overall outcome.31 This was probably due to the use of clinical criteria in the GUSTO bleeding definitions.31 For the long-term prognosis, Doyle et al. found that the risk of major femoral bleeding is as important as late bleeding events such as gastrointestinal or intracranial bleeding.32 There is also suspicion of a potentially harmful effect of blood transfusion.26 Possible mechanisms include microbial transmission and antibody reactions.26 After blood transfusion, an independent association with increased mortality was shown.26,32 The duration of storage of transfused blood could also be an independent risk factor.33 The question remains whether the bleeding events themselves or the associated comorbidity (advanced age, renal failure, triple therapy which are risk factors for bleeding) is responsible for the increased mortality. Thus, reducing bleeding risk and developing a strategy for more targeted and safer blood transfusions could also reduce mortality rates.26 Apart from the radial versus femoral approach, seven variables were identified to be associated with higher bleeding risk: age >55 years, female sex, glomerular filtration rate <60 ml/min, pre-existing anaemia, use of low-molecular-weight heparins <48 hours before PCI, use of GP IIb/IIIa inhibitors and the use of an intra-aortic balloon pump.34,35 Of course, the use of bare metal stents when indicated will reduce bleeding risk because the need of clopidogrel can be reduced to one month. This is also one of the measures mentioned by the 2008 ESC guidelines.8 Using proton pomp inhibitors could also help to limit bleeding from the gastrointestinal tract but there is some concern because omeprazole decreased platelet activity in an in vitro setting.36-39 This will be discussed in the next paragraph. An aid to facilitate decision-making for each individual patient is proposed in table 1.

| TIMI bleeding definitions29,31 | GUSTO bleeding definitions30,31 | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Major | Intracranial haemorrhage or a 5 g/dl decrease in the haemoglobin concentration or a 15% absolute decrease in the haematocrit | Severe | Either intracranial haemorrhage or bleeding that causes haemodynamic compromise and requires intervention |

| Minor | Observed blood loss: 3 g/dl decrease in the haemoglobin concentration or 10% decrease in the haematocritNo observed blood loss: 4 g/dl decrease in the haemoglobin concentration or 12% decrease in the haematocrit | Moderate | Bleeding that requires blood transfusion but does not result in haemodynamic compromise |

| Minimal | Any clinically overt sign of haemorrhage (including imaging) that is associated with a 3 g/dl decrease in the haemoglobin | Mild | Bleeding that does not meet criteria for either severe or moderate bleeding |

Ranitidine or proton pomp inhibitors?

Since most bleeding with triple therapy occurs in the gastrointestinal tract, protection of the gastric mucosa seems crucial. However, a possible interaction between certain proton pomp inhibitors (PPI) and clopidogrel might reduce the antiplatelet effect.4,5,13,21,38,40,41 By omitting aspirin, the combination of oral anticoagulants and clopidogrel has a theoretical advantage that there are no local erosive effects of aspirin on the stomach. Gilard et al. found that omeprazole decreased the effect of clopidogrel on platelets as tested by vasodilator-stimulated phosphoprotein (VASP) phosphorylation after seven days.38 However, in this study, there were no clinical endpoints and no clinical differences between the two groups after seven days, so any assumptions of an in vivo effect might be premature. In addition, a retrospective cohort study of 8205 patients showed concomitant use of clopidogrel and PPI after hospital discharge for acute coronary syndrome was associated with an increased risk of adverse outcomes suggesting that use of PPI may be associated with attenuation of benefits of clopidogrel.39 However, since these studies are retrospective, it is too early to draw any conclusions. A second possibility is that in acute coronary syndrome PPI are given to a high-risk population and that this could lead to a bias. In contrast to omeprazole, the intake of pantoprazole and esomesoprazole is not associated with impaired response to clopidogrel.42 An analysis of 13,809 patients undergoing acute and elective percutaneous coronary stenting in the TIMI-TRITON 38 and TIMI-TRITON 44 trials does not support the need to avoid concomitant use of PPI and clopidogrel or prasugrel.37 Bhatt recently presented the results of the COGENT trial in which patients after acute coronary syndrome were randomised to clopidogrel 75 mg + omeprazole 20 mg or clopidogrel 75 mg + placebo. These preliminary data show that the combination of omeprazole and clopidogrel is associated with a reduction in composite GI events when used in patients who are not at an especially high risk for GI bleeding.36 These data thus indicate that the concomitant use of omeprazole in patients on dual antiplatelet therapy (even in those who are not at high risk for GI bleeding) should not be avoided, but probably encouraged. These results also raise questions about the exact relationship between the in vitro platelet assays and the clinical outcomes.36 Further randomised prospective studies on this issue are also mandatory to solve the issue. We conclude that to this date, there is insufficient evidence to support the switch of proton pomp inhibitors to ranitidine.

Another issue for clopidogrel, an inhibitor of platelet P2Y12 receptor, is there are data suggesting that genetics may affect drug responsiveness and efficacy. A reduced response to clopidogrel has been associated with the CYP2C19*2 allele, which causes loss of function in patients after stent placement and after myocardial infarction without ST elevation.43-45 Shuldiner et al. found people with the loss-of-function cytochrome (CYP) P4502C19*2 variant were twice as likely as those without the variant to sustain an ischaemic event in the year following PCI.44,46 Potentially, higher doses of clopidogrel could overcome this impaired antiplatelet response. Newer ADP receptor antagonists, such as prasugrel and ticagrelor, could be used instead of clopidogrel.44,46 The use of direct thrombin inhibitors or factor Xa inhibitors might also be a solution for this problem in the future.

Peri-procedural management

In patients receiving oral anticoagulant therapy, this therapy is often discontinued some days before a percutaneous intervention, exposing the patient to the risk of thromboembolic complications. Occasionally, the periods (before and after the intervention until a therapeutic INR is reached) are bridged with additional unfractionated heparin or low-molecular-weight heparins exposing the patient to excess bleeding risk. The risk is especially high when patients are given a short period of quadruple therapy after the intervention until a therapeutic INR is reached again. A possible solution to this problem is to consider a radial approach, in which anticoagulation therapy can be continued. In the BAAS study, it was shown that oral anticoagulant therapy started before coronary angioplasty can safely be continued peri-procedurally without an increase in bleeding episodes.47 It is clear that GP IIb/IIIa inhibitors added to triple therapy result in an unacceptably high bleeding risk and therefore should be avoided.14

Ongoing trials

The WOEST trial (What is the Optimal antiplatElet & anticoagulant therapy in patients with oral anticoagulation and coronary StenTing) is a prospective randomised international multicentre open-label trial that assesses the hypothesis that after PCI with stent implantation in patients on oral anticoagulant therapy, the combination of oral anticoagulation therapy and clopidogrel 75 mg/day is safe and superior to triple therapy treatment with respect to the prevention of thrombotic complications because of a reduction in bleeding risk. The primary outcome is the combination of TIMI and GUSTO minor and major bleeding events up to 30 days and one year. The secondary outcomes are major adverse cardiac events. The sample size is 496.17 The ISAR TRIPLE trial (Intracoronary Stenting and Antithrombotic Regimen: Testing of a Six-Week Versus a Six-Month Clopidogrel Treatment Regimen in Patients With Concomitant Aspirin and Oral Anticoagulant Therapy Following Drug-Eluting Stenting) is a trial in which 600 patients will be recruited. The aim of this study is to compare a six-week versus a six-month triple therapy after DES implantation. Primary endpoint is a combination of MACCE and major bleeding.48 The AFCAS trial (Management of Patients With Atrial Fibrillation Undergoing Coronary Artery Stenting) is an observational, multicentre, prospective registry including patients with atrial fibrillation undergoing PCI in which 1000 patients will be recruited. Follow-up time is 12 months. Primary endpoints are major haemorrhagic and thrombotic/thromboembolic complications including cardiac death, and secondary endpoints are major adverse cardiac events.49 All these prospective studies are expected to end before the end of 2012 and will help to define new guidelines for patients with chronic indication for chronic anticoagulation who need coronary stenting.

New medication

The search for newer and better medication is on: As mentioned above, ticagrelor (a reversible ADP receptor antagonist), and prasugrel (a more potent thienopyridine than clopidogrel but similarly an irreversible ADP receptor antagonist) could overcome the problem of the clopidogrel loss-of-function cytochrome (CYP) P4502C19*2 variant. The PLATO trial showed ticagrelor to significantly reduce the rate of death, myocardial infarction and stroke without increased bleeding as compared with clopidogrel in patients with acute coronary syndrome.50 This medication is currently not available for commercial use. Montalescot et al. showed that prasugrel is more effective than clopidogrel in patients with STEMI undergoing PCI.51 In this TRITON TIMI 38 substudy, an exclusion criterion was excess bleeding risk, so prasugrel does not seem to be an ideal candidate to combine with oral anticoagulant therapy. Recently a huge breakthrough was seen for the oral thrombin blocker dabigatran. In patients with atrial fibrillation, as compared with warfarin, administration of dabigatran was associated with lower rates of stroke and systemic embolism but similar rates of major haemorrhage. In this study patients with conditions that increased the risk for bleeding were excluded.52 So, this means additional randomised trials are needed to evaluate the combined use of dabigatran, aspirin and clopidogrel.

Conclusion

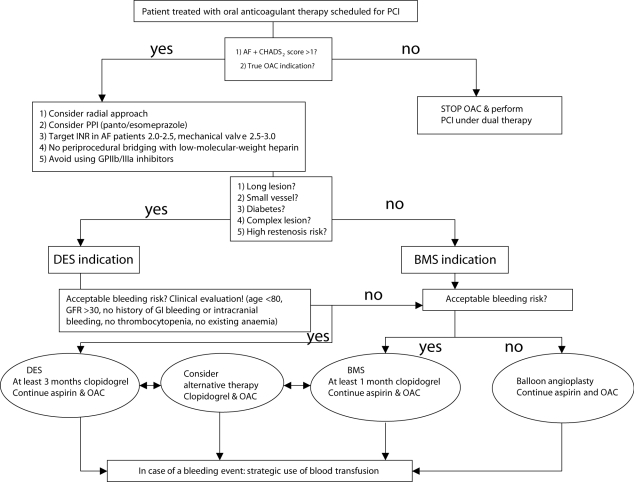

Chronic oral anticoagulant treatment is mandatory in patients with mechanical heart valves and in many patients with atrial fibrillation. When these patients undergo PCI with stenting, there is also an indication for treatment with aspirin and clopidogrel. However, triple therapy is known to increase the risk of bleeding complications. We have tried to identify all the possible pitfalls and propose a diagram (as shown in figure 1) as an aid for the treatment of these patients with complex combination of pathologies

Figure 1.

Individual approach to patients with indication for triple therapy.

References

- 1.Fuster V, Ryden LE, Cannom DS, Crijns HJ, Curtis AB, Ellenbogen KA, et al.; ACC/AHA/ESC 2006 guidelines for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation-executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on practice guidelines and the European Society of Cardiology Committee for Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Revise the 2001 Guidelines for the Management of Patients with Atrial Fibrillation). Eur Heart J. 2006;16:1979-2030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bonow RO, Carabello BA, Kanu C, de Leon AC Jr, Faxon DP, Freed MD, et al. American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines; Society of Cardiovascular Anesthesiologists; Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions; Society of Thoracic Surgeons. ACC/AHA 2006 guidelines for the management of patients with valvular heart disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (writing committee to revise the 1998 Guidelines for the Management of Patients With Valvular Heart Disease): developed in collaboration with the Society of Cardiovascular Anesthesiologists: endorsed by the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions and the Society of Thoracic Surgeons. Circulation. 2006;114(5):e84-231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smith SC Jr, Feldman TE, Hirshfeld JW Jr, Jacobs AK, Kern MJ, King SB 3rd, et al. American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines; American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association/Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions Writting Committee to Update the 2001 Guidelines for Percutaneous Coronary Intervention. ACC/AHA/SCAI 2005 Guideline Update for Percutaneous Coronary Intervention--summary article: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (ACC/AHA/SCAI Writing Committee to Update the 2001 Guidelines for Percutaneous Coronary Intervention). Circulation. 2006;113:156-75. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Karjalainen PP, Porela P, Ylitalo A, Vikman S, Nyman K, Vaittinen MA, et al. Safety and efficacy of combined antiplatelet-warfarin therapy after coronary stenting. Eur Heart J. 2007;28:726-32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Orford JL, Fasseas P, Melby S, Burger K, Steinhubl SR, Holmes DR, et al. Safety and efficacy of aspirin, clopidogrel, and warfarin after coronary stent placement in patients with an indication for anticoagulation. Am Heart J. 2004;147:463-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Connolly S, Pogue J, Hart R, Pfeffer M, Hohnloser S, Chrolavicius S, et al.; ACTIVE Writing Group on behalf of the ACTIVE Investigators. Clopidogrel plus aspirin versus oral anticoagulation for atrial fibrillation in the Atrial fibrillation Clopidogrel Trial with Irbesartan for prevention of Vascular Events (ACTIVE W): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2006;367:1903-12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Antman EM, Hand M, Armstrong PW, Bates ER, Green LA, Halasyamani LK, et al. 2007 Focused Update of the ACC/AHA 2004 Guidelines for the Management of Patients With ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines: developed in collaboration With the Canadian Cardiovascular Society endorsed by the American Academy of Family Physicians: 2007 Writing Group to Review New Evidence and Update the ACC/AHA 2004 Guidelines for the Management of Patients With ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction, Writing on Behalf of the 2004 Writing Committee.Circulation. 2008;117:296-329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Van de Werf F, Bax J, Betriu A, Blomstrom-Lundqvist C, Crea F, Falk V, et al. Management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with persistent ST-segment elevation: the Task Force on the Management of ST-Segment Elevation Acute Myocardial Infarction of the European Society of Cardiology.Eur Heart J. 2008;23:2909-45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lip GY. Managing the anticoagulated patient with atrial fibrillation at high risk of stroke who needs coronary intervention. BMJ. 2008;337:a840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ruiz-Nodar JM, Marín F, Hurtado JA, Valencia J, Pinar E, Pineda J, et al. Anticoagulant and antiplatelet therapy use in 426 patients with atrial fibrillation undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention and stent implantation implications for bleeding risk and prognosis.J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;51:818-25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Leon MB, Baim DS, Popma JJ, Gordon PC, Cutlip DE, Ho KK, et al. A clinical trial comparing three antithrombotic-drug regimens after coronary-artery stenting. Stent Anticoagulation Restenosis Study Investigators. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:1665-71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rubboli A, Milandri M, Castelvetri, Cosmi B. Meta-analysis of trials comparing oral anticoagulation and aspirin versus dual antiplatelet therapy after coronary stenting. Clues for the management of patients with an indication for long-term anticoagulation undergoing coronary stenting. Cardiology. 2005;104:101-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rubboli A, Halperin JL, Airaksinen KE, Buerke M, Eeckhout E, Freedman SB, et al. Antithrombotic therapy in patients treated with oral anticoagulation undergoing coronary artery stenting. An expert consensus document with focus on atrial fibrillation.Ann Med. 2008;40:428-36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rubboli A, Halperin JL. Pro: 'Antithrombotic therapy with warfarin, aspirin and clopidogrel is the recommended regime in anticoagulated patients who present with an acute coronary syndrome and/or undergo percutaneous coronary interventions'.Thromb Haemost. 2008; 100:752-3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Roldán V, Marín F: Contra: 'Antithrombotic therapy with warfarin, aspirin and clopidogrel is the recommended regimen in anticoagulated patients who present with an acute coronary syndrome and/or undergo percutaneous coronary interventions'. Not for everybody.Thromb Haemost. 2008;100:754-5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dewilde W, Ten Berg JM. The Antithrombotic dilemma. Future Cardiology, 2007;3: 511-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dewilde W, Ten Berg JM. Trial design: WOEST Trial: What is the Optimal antiplatElet & anticoagulant therapy in patients with oral anticoagulation and coronary StenTing: Am Heart J. 2009;158:713-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yusuf S, Mehta SR, Chrolavicius S, Afzal R, Pogue J, Granger CB, et al.; Fifth Organization to Assess Strategies in Acute Ischemic Syndromes Investigators. Comparison of fondaparinux and enoxaparin in acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:1464-76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sibbing D, Morath T, Stegherr J, Braun S, Vogt W, Hadamitzky M, et al. Impact of concomitant oral anticoagulation with a coumarine derivate on the antiplatelet effects of clopidogrel [Presented at ESC 2009] Eur Heart J. 2009;30, abstract supplement, 884 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Buresly K, Eisenberg MJ, Zhang X, Pilote L. Bleeding complications associated with combinations of aspirin, thienopyridine derivatives, and warfarin in elderly patients following acute myocardial infarction. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165:784-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mattichak SJ, Reed PS, Gallagher MJ, Boura JA, O'Neill WW, Kahn JK. Evaluation of safety of warfarin in combination with antiplatelet therapy for patients treated with coronary stents for acute myocardial infarction. J Interv Cardiol. 2005;18:163-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gilard M, Blanchard D, Helft G, Carrier D, Eltchaninoff H, Belle L, et al.; STENTICO Investigators. Antiplatelet therapy in patients with anticoagulants undergoing percutaneous coronary stenting (from STENTIng and oral antiCOagulants [STENTICO]).Am J Cardiol. 2009;104:338-42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schömig A, Sarafoff N, Seyfarth M. Triple antithrombotic management after stent implantation: when and how?Heart. 2009;95:1280-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Connolly S, Pogue J, Hart RG, Hohnloser SH, Pfeffer M, Chrolavicius S, et al.; ACTIVE Investigators. Effect of clopidogrel added to aspirin in patients with atrial fibrillation.N Engl J Med. 2009;360:2066-78.19336502 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zinn A, Feit F. Optimizing antithrombotic strategies in patients with concomitant indications for warfarin undergoing coronary artery stenting.Am J Cardiol. 2009;104(5 Suppl):49C-54C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Doyle BJ, Rihal CS, Gastineau DA, Holmes DR Jr. Bleeding, blood transfusion, and increased mortality after percutaneous coronary intervention: implications for contemporary practice.J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;53:2019-27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stone GW, McLAurin BT, Cox DA, Bertrand ME, Lincoff AM, Moses JW, et al.; ACUITY Investigators. Bivalirudin for patients with acute coronary syndromes.N Engl J Med. 2006;355:2203-16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Moscucci M, Fox KA, Cannon CP, Klein W, López-Sendón J, Montalescot G, et al. Predictors of major bleeding in acute coronary syndromes: the Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events (GRACE).Eur Heart J. 2003;24(20):1815-23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chesebro JH, Knatterud G, Roberts R, et al. Thrombolysis In Myocardial Infarction (TIMI) trial, phase I: a comparison between intravenous tissue plasminogen activator and intravenous streptokinase. Clinical findings through hospital discharge. Circulation. 1987;76:142-54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.The Gusto Investigators. An international randomized trial comparing four thrombolytic strategies for acute myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 1993;329:673-82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rao SV, O'Grady K, Pieper KS, Granger CB, Newby LK, Mahaffey KW, et al. A comparison of the clinical impact of bleeding measured by two different classifications among patients with acute coronary syndromes.J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006 1;47:809-16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Doyle BJ, Ting HH, Bell MR, Lennon RJ, Mathew V, Singh M, et al. Major femoral bleeding complications after percutaneous coronary intervention: incidence, predictors, and impact on long-term survival among 17,901 patients treated at the Mayo Clinic from 1994 to 2005.JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2008;1:202-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Koch CG, Li L, Sessler DI, Figueroa P, Hoeltge GA, Mihaljevic T, et al. Duration of red-cell storage and complications after cardiac surgery.N Engl J Med. 2008;358:1229-39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nikolsky E, Mehran R Dangas G, Fahy M, Na Y, Pocock SJ, et al. Development and validation of a prognostic risk score for major bleeding in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention via the femoral approach.Am J Cardiol. 2007;99:1055-61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chase A, Fretz EB, Warburton WP, Klinke WP, Carere RG, Pi D, et al. Association of the arterial access site at angioplasty with transfusion and mortality: the M.O.R.T.A.L study (Mortality benefit Of Reduced Transfusion after percutaneous coronary intervention via the Arm or Leg).Heart. 2008;94:1019-25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bhatt D, Cryer B, Constant C, Cohen M., Lanas A, Schnitzer T, et al. The COGENT trial. Presented at TCT 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 37.O' Donoghue ML, Braunwald E, Antman EM, Murphy SA, Bates ER, Rozenman Y, et al. Pharmacodynamic effect and clinical efficacy of clopidogrel and prasugrel with or without a proton-pump inhibitor: an analysis of two randomised trials.Lancet. 2009;374:989-97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gilard M, Arnaud B, Cornily J, Le Gal G, Lacut K, Le Calvez G, et al. Influence of omeprazole on the antiplatelet action of clopidogrel associated with aspirin: the randomized, double-blind OCLA (Omeprazole CLopidogrel Aspirin) study.J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;51:256-60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ho PM, Maddox TM, Wang L, Fihn SD, Jesse RL, Peterson ED, et al. Risk of adverse outcomes associated with concomitant use of clopidogrel and proton pump inhibitors following acute coronary syndrome.JAMA. 2009;301:937-44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Khurram Z, Chou E, Minutello R, Bergman G, Parikh M, Naidu S, et al. Combination therapy with aspirin, clopidogrel and warfarin following coronary stenting is associated with a significant risk of bleeding.J Invasive Cardiol. 2006;18:162-4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Porter A, Konstantino Y, Iakobishvili Z Shachar L, Battler A, Hasdai D. Short-term triple therapy with aspirin, warfarin, and a thienopyridine among patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention.Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2006;68:56-61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Siller Matula JM, Spiel AO, Lang IM, Kreiner G, Christ G, Jilma B. Effects of pantoprazole and esomeprazole on platelet inhibition by clopidogrel.Am Heart J. 2009;157:148.e1-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Freedman JE, Hylek EM. Clopidogrel, genetics, and drug responsiveness.N Engl J Med. 2009;360:411-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mega JL, Close SL, Wiviott SD, Shen L, Hockett RD, Brandt JT, et al. Cytochrome p-450 polymorphisms and response to clopidogrel.N Engl J Med. 2009;360:354-62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Simon T, Verstuyft C, Mary-Krause M, Quteineh L, Drouet E, Méneveau N, et al.; for the French Registry of Acute ST-Elevation and Non-ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction (FAST-MI) Investigators: Genetic determinants of response to clopidogrel and cardiovascular events.N Engl J Med. 2009;360:363-75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shuldiner AR, O'Connell JR, Bliden KP, Gandhi A, Ryan K, Horenstein RB, et al. Association of cytochrome P450 2C19 genotype with the antiplatelet effect and clinical efficacy of clopidogrel therapy.JAMA. 2009;302:849-57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.ten Berg JM, Hutten BA, Kelder JC, Verheugt FW, Plokker HW. Oral anticoagulant therapy during and after coronary angioplasty the intensity and duration of anticoagulation are essential to reduce thrombotic complications. Circulation. 2001;103:2042-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schömig A. ISAR-TRIPLE: Triple therapy in Patients on Oral Anticoagulation After Drug Eluting Stent Implantation: trial design: www. Clinicaltrial.gov. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Airaksinen JKE.AFCAS: Management of Patients With Atrial Fibrillation Undergoing Coronary Artery Stenting: www. Clinicaltrial.gov. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wallentin L, Becker RC, Budaj A, Cannon CP, Emanuelsson H, Held C, et al.; PLATO Investigators. Ticagrelor versus clopidogrel in patients with acute coronary syndromes.N Engl J Med. 2009;361:1045-57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Montalescot G, Wiviott SD, Braunwald E, Murphy SA, Gibson CM, McCabe CH, et al.; TRITON-TIMI 38 investigators. Prasugrel compared with clopidogrel in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention for ST-elevation myocardial infarction (TRITON-TIMI 38): double-blind, randomised controlled trial.Lancet. 2009;373:723-31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Connolly SJ, Ezekowitz MD, Yusuf S, Eikelboom J, Oldgren J, Parekh A, et al.; RE-LY Steering Committee and Investigators. Dabigatran versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation.N Engl J Med. 2009;361:1139-51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]