Abstract

This article describes how the social context of transculturation (cultural change processes) and transmigration (migration in which relationships are sustained across national boundaries) can directly influence use of mammography screening. The authors conducted semistructured interviews with Latino and Filipino academics and social service providers and with U.S.-born and immigrant Latinas and Filipinas to explore direct and indirect influences of social context on health behavior (Behavioral Constructs and Culture in Cancer Screening study). Iterative analyses identified themes of the transcultural domain: colonialism, immigration, discrimination, and therapeutic engagement. In this domain, the authors examine two key behavioral theory constructs, perceptions of susceptibility to illness and perceptions of benefits of preventive medical care. The findings raise concerns about interventions to promote mammography screening primarily based on provision of scientific information. The authors conclude that social context affects behavior directly rather than exclusively through beliefs as behavioral theory implies and that understanding contextual influences, such as transculturation, points to different forms of intervention.

Keywords: mammography screening, perceived benefits, perceived susceptibility, transculturation, health disparities

Health behavior theory predominantly relies on individual-focused cognitive models of rational decision making, which are explicitly abstracted from social context, to explain health related behavior (Glanz, Rimer, & Lems, 2002). However, many health behavior experts now question the presumed rationality of this process (Resnicow & Page, 2008). Two core constructs of the health behavior theories often used to explain and predict cancer screening behavior are perceived susceptibility (PS) and perceived benefits (PB). These constructs were developed for a generic U.S. population; however, little data exist on whether concepts of health, illness, susceptibility, and benefits are uniformly meaningful throughout the diverse U.S. population. For the most part, researchers have not explored the question of variable meanings or whether adaptations of the constructs are needed for specific subgroups (Glanz et al., 2002). Also missing from the behavioral theory literature is consideration of whether or how to take into account specific and powerful social contexts such as poverty and migration.

Social context, the conceptual framework for this study, is defined as the sociocultural forces that shape people's day-to-day experiences and that directly and indirectly affect health and behavior (Burke, Joseph, Pasick, & Barker, 2009; Pasick & Burke, 2008). These forces include historical, political, and legal structures and processes (e.g., colonialism and migration), organizations and institutions (e.g., schools and health care clinics), and individual and personal trajectories (e.g., family, community). Notably, these forces are co-constitutive, meaning they are formed in relation to each other. Our approach to understanding social context is inductive and is based in the social science disciplines of anthropology and sociology. Burke, Joseph, et al. (2009) describe this framework in detail and show how it complements and differs from dominant models such as social learning theory and the social ecological model, dominant models in the study of behavior and health outcomes.

BACKGROUND

The 5-year multimethod study described in this volume and on which this article is based (Behavioral Constructs and Culture in Cancer Screening study [3Cs]) arose from a series of trials (e.g., Hiatt et al., 1996) to increase mammography use in low-income, multiethnic communities. The results of the trials raised questions about the cross-cultural appropriateness of concepts and measures associated with the five behavioral theory constructs most commonly used to explain and influence cancer screening: (a) PB (beliefs about the positive outcomes associated with a behavior in response to a real or perceived threat; Rosenstock, 1974), (b) PS (an individual's belief about the likelihood of a health threat's occurrence or the likelihood of developing a health problem; M. H. Becker, 1974), (c) self-efficacy (the belief that a person has the ability to complete an action; Bandura, 1986), (d) intention (behavioral plans that enable attainment of a behavioral goal; Ajzen, 1991, 1996; Bandura, 1986), and (e) subjective norms (beliefs about the extent to which other people who are important to them think they should or should not perform particular behaviors; Fishbein & Ajzen, 1975). The 3Cs study was designed to assess the cultural appropriateness of these five behavioral theory constructs related to the practice of mammography screening among Filipinas and Latinas and to explore and describe the meanings and social context associated with each construct through inductive research methods.

Methods for the 3Cs study were chosen to foster a multidimensional understanding of the social context of women's lives and women's orientation to health and preventive practices such as mammography screening. These methods are detailed by Pasick, Burke, et al. (2009) and are summarized below. It is important that this study does not attempt to characterize or to compare Filipinas and Latinas. Rather, it explores sociocultural context in two immigrant populations whose experiences exemplify a range of differences from the U.S. European American middle-class mainstream. The similarities of these populations, in terms of social context (e.g., colonialism, immigration, discrimination, therapeutic engagement), are our focus in analyzing the appropriateness of the behavioral constructs examined in the 3Cs study. We chose these two groups because (a) they have low rates of breast cancer screening (Kagawa-Singer et al., 2007), (b) they were included in our quantitative study already under way and we had the most prior data collection and intervention experience with them, (c) they are well represented in the San Francisco Bay area, which is 4.8% Filipino and 19.4% Latino (Bay Area Census, 2000), and (d) both were represented by members of our team allowing for the important insider–outsider research perspectives (Kagawa-Singer, 2000). Most of the research that attempts to understand behavior and develop interventions is based on theories that were neither developed nor tested in these or other immigrant populations.

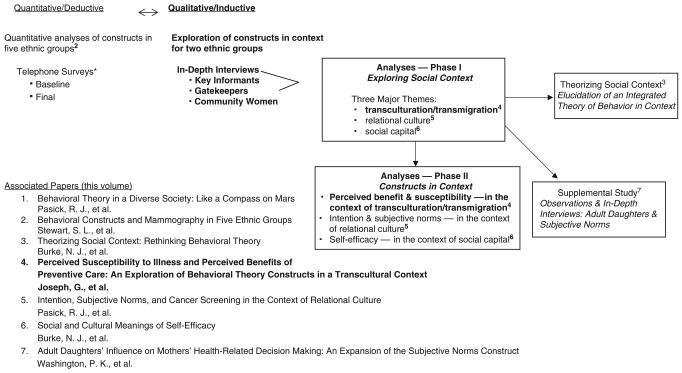

Among the findings of the 3Cs study was the identification of three overarching domains of social context that pervade daily life and were described throughout all the interviews. These are social capital (benefits that accrue from participation in social networks and groups), relational culture (the processes of interdependence and interconnectedness among individuals and groups and the prioritization of these connections above virtually all else), and transculturation and transmigration (cultural change processes and migration in which relationships are sustained across national boundaries, respectively). Although these domains are inextricably interconnected in complex ways with implications for all the constructs, for reporting purposes we identified the most significant context–construct linkages and conducted analyses to explore the meaning of self-efficacy in the context of social capital (Burke, Bird, et al., 2009), intention and subjective norms vis-à-vis relational culture (Pasick, Barker, et al., 2009), and PS and PB in the context of transculturation, the focus of this report. Figure 1 shows the 3Cs study design and the relationship of this analysis to the study as a whole.

Figure 1.

Behavioral Constructs and Culture in Cancer Screening (3Cs) study design and associated reports.

*Access and Early Detection for the Underserved, Pathfinders (1998 to 2003), a mammography and Pap screening intervention trial under way when 3Cs began.

We begin by providing background on the constructs of PS and benefits, their applications in diverse communities, and their limitations. A brief explication of transculturation and transmigration follows. Together, these form a framework for assessing the relevance of the two constructs for foreign-born and first-generation Filipina and Latina immigrants.

Perceived Susceptibility and Perceived Benefits in Cancer Control Research

Two core constructs of the health belief model (HBM; Rosenstock, 1974) are PS and PB, and PB is also a component of “decisional balance” as “pros” in the transtheoretical model (Prochaska, 1979). These constructs, in combination with others such as perceived barriers and cues to action (Rosenstock, 2005) have been used to explain and predict individual health behavior and to inform and evaluate a multitude of health intervention strategies.

Studies and/or interventions that utilize PS and PB share the assumption (based on a model of rational action) that people will take action to prevent, to screen for, or to control illness if they (a) believe that they are susceptible to that illness, especially if they view the illness as potentially having serious consequences to them; (b) believe that by following a recommended health action (e.g., cancer screening), they would reduce their susceptibility to or the severity of the illness; and (c) believe that the benefits of taking the recommended action outweigh the perceived barriers or costs for doing so (Janz, Champion, & Stecher, 1995). These constructs also tacitly assume first that when presented in an appropriate manner people will believe in scientific principles (e.g., tumors start small, at the presymptomatic cellular level, where they are still treatable and grow to being untreatable because of natural biologic processes). A second assumption is that people trust that the health care system and that its health information messages (the primary intervention associated with PS and PB) will effectively serve them (i.e., the health care system has the will and ability to intervene equally successfully in this biologic process for everyone). Thus, an underlying assumption is that decisions about screening behaviors are reached through a deliberate reasoning process or “an analysis of susceptibility, potential actions, potential costs, and anticipated outcomes” (Katapodi, Lee, Facione, & Dodd, 2004, p. 389).

The health behavior theories that employ the constructs of PS and PB, particularly HBM (Rosenstock, 1974), are derived from a cognitive model of behavior (e.g., Bandura, 1986; Krumeich, Weijts, Reddy, & Meijer-Weitz, 2001). Hence, the constructs of PS and PB are based in a model of individual, rational decision making and personal agency that treats any form of context—social, cultural, political, economic, or historical—as a distal influence on beliefs. In her 1999 review of risk perception and risk communication research, Vernon concluded, “Attitudes and beliefs do not develop in a vacuum … an individual's choice is largely determined by social structural conditions” (p. 116). The major theorists who ascribe to the HBM model contend that these “background factors” are important only insofar as they affect the beliefs that determine behavior (Bandura, 1986). As such, they do not warrant the scrutiny that is devoted to more proximal beliefs and attitudes. We examine these assumptions in the context of transculturation and transmigration because little research has explored the meanings of PS and PB for diverse populations. Here, we use the term meanings not as correct or incorrect understandings of health information or attitudes or beliefs but rather as interpretations of benefits of medical intervention or susceptibility to an illness that are formed by and make sense within a given cultural and social context, often without conscious awareness. Although medical anthropology research shows that health and illness are conceived differently in various cultural and social groups (e.g., Helman, 2007; Kleinman, 1981), health behavior researchers have rarely explored the question of meaning or how social contexts shape meanings of health behavior for diverse population groups.

It is important that health behavior researchers have begun to confront the limitations of their theory in attempts to apply the constructs to diverse populations. Although perceived threat (combination of PS and perceived severity) has proved useful in the design of interventions to increase cancer screening with certain populations (e.g., Champion & Huster, 1995), findings are inconsistent across cultural and socioeconomic contexts; studies conducted with African Americans and Latinos have produced mixed results and suggest that the measures are not universally applicable (e.g., Duke, Gordon-Sosby, Reynolds, & Gram, 1994; Richardson et al., 1987). Champion and Scott (1997) adapted the HBM for African American women with culturally sensitive scales based on the conviction that “validity and reliability are population specific.” However, their findings and subsequently those of Wu and Yu (2003), who adapted Champion's scales for Chinese American women, indicated that although the internal and test–retest reliabilities of the revised scales were strong, the variance accounted for in predicting mammography behavior was inadequate. Ashing-Giwa (1999) found for African Americans and Emmons et al. (2005) for “working class and multiethnic populations” that HBM has limited relevance because of its lack of attention to social context.

Yarbrough and Braden's 2001 review of 16 descriptive studies employing HBM with regard to breast cancer screening behaviors (self-breast exam, clinical exam, or mammogram) concluded that the model cannot consistently predict screening behaviors such as mammography, in part because it does not account for the social meaning of breast cancer and cancer screening and does not define and describe contextual influences or essential factors influencing screening. Pasick and Burke (2008) observed that HBM constructs inadequately explain complex behavior because they “place narrowly defined determinants of behavior in a specific relationship to one another, entirely isolated from social context.” As a result they “shed little new light and point primarily to knowledge- and information oriented interventions” (p. 354).

Finally, for the deductive quantitative component of the 3Cs study, Stewart, Rakowski, and Pasick's (2009) assessment of the predictive validity of PB in five ethnic groups (African American, Chinese, Filipina, Latina, and White) found mixed results. This analysis used five components of PB (benefit of early detection, control over health, good for family, peace of mind, and lower mortality) and a PB summary score. Responses to all the component questions were overwhelmingly affirmative (i.e., the vast majority of women, regardless of ethnicity, answered yes), limiting the specificity of the measures as predictors of mammography (many women who agreed with the benefits of screening had not obtained a recent mammogram 2 years later). As a result, it was difficult to detect a statistically significant race/ethnic interaction, which would have been stronger evidence that this construct better predicts screening for one or more groups compared with the others. All five components predicted recent mammogram for women overall, and some of the benefits predicted screening among African American, Filipina, and/or White women. The belief that having a mammogram is good for one's family significantly predicted recent mammogram in the sample overall (odds ratio [OR] = 1.8, 95% confidence interval [CI] = 1.1, 2.8), but not for any of the ethnic groups. The PB of lower mortality significantly predicted screening only for Filipina women (OR = 3.6, 95% CI = 1.1, 11). No significant race/ethnicity interaction was found for any of the PB. The authors concluded that the decision to get a mammogram may be based on considerations other than the relationship of the test to breast cancer outcomes.

Researchers have addressed other limitations of HBM theory, such as its inability to account for affect and emotional responses to risk as well. For example, recent research in cognitive neuroscience examines how rational decision making combines with “experiential” or intuitive responses in risk perception and associated decision making. Although this affective, experiential component of risk perception has in common with ours an unconscious process or the influence of past experiences, Slovic, Finucane, Peters, and MacGregor (2004) attributed it to “ancient instincts” and “our evolutionary journey” without considering culture and social context. Decruyenaere, Evers-Kiebooms, Welkenhuysen, Denayer, and Claes (2000) attempted to address the emotional aspect of risk perception through the self-regulatory model of illness, which “suggests that health-related behaviors are influenced by a person's health threat representation that consists of an interacting cognitive and emotional part” (p. 528). In this case, the “emotional part” is limited to psychological factors, and again, sociocultural context is not explored as a potential influence on these emotional, cognitive, or behavioral responses to health issues (Decruyenaere et al., 2000).

Culture, Transculturation, and Transmigration

Social context includes both cultural and social determinants of health and health care decision making. We understand culture (in an anthropological sense) as the patterned process of people making sense of their world and the conscious and unconscious assumptions, expectations, and practices they call on to do so. The term patterned indicates that despite variation culture is not random; instead, there are consistencies within culture that are at the same time flexible and situationally responsive. Culture is the outcome of a group of people and their diverse, often overlapping, sometimes contradictory, creative attempts to make sense of their world and live in it (Bourdieu, 1990; Geertz, 1973). People bring culture into being as they go about making their world—the structures, institutions, rituals, and beliefs that reflect and (re)produce their sense-making activities.

Culture is not synonymous with ethnicity or race. Rather, culture is integral to all social structures and institutions (religion, politics, kinship, class dynamics), including social determinants of health such as poverty. Rather than a discrete, measurable “factor” with fixed or clear boundaries, culture is a process that changes over time and across space, whether groups are in contact or in isolation. As G. Becker and Newsom summarized,

Culture is constantly redefined and renegotiated, and it must be interpreted within the context of individual history, family constellation, and SES. … Without acknowledging both cultural background and social class, analyses of specific groups are incomplete and may overlook important influences that profoundly affect people's health. (p. 742)

Rationality is culturally and socially specific; a rational choice in one context may seem irrational or illogical in another. What is more, people do not necessarily choose behaviors in a conscious, rational manner. Some of the influences on their behavior are outside of their conscious awareness, rooted in historical and institutional precedents (Bourdieu, 1990). Thus, the meanings that people hold for practices such as mammography and cervical exams and concepts such as health and illness can vary dramatically across populations and contexts, shaping cognition and logic (Geertz, 1973; Kleinman, 1981). In other words, behavior and thought are shaped by contingent circumstances rather than predetermined (Lambert & McKevitt, 2002).

Transculturation, a framework developed in anthropology and cultural studies, accounts for the complexity, contingencies, and creativity or spontaneity (as opposed to predetermination) involved in cultural change processes (Coronil, 1995; Pratt, 1992). Although originally developed in Cuba in the 1930s to explain cultural transformations that occurred in the context of Cuba's history of Spanish colonization, African slavery, and U.S. imperialism (Ortiz, 1995), the concept of transculturation addresses some of the recent critiques of “acculturation”—a concept that has been used for decades in health research to ascertain the association among cultural change, health behavior, and health outcomes. Primarily measured through variables such as immigrant status and language of origin, the concept of acculturation assumes, problematically, that people move in a linear fashion from one discreet cultural identity to another, losing one culture in the adoption of another (Abraído-Lanza, Armbrister, Flórez, & Aguirre, 2006). In this implied continuum, definitions of the two poles (mainstream–White and marginal–ethnic minority) tend to be presumed rather than described, and a static notion of culture as equivalent to ethnicity/race is more often assumed than explored as a dynamic process (Hunt, Scheider, & Comer, 2004). In contrast, the concept of transculturation expands on acculturation to encompass multidimensional cultural transformations by accounting for structural (historical, economic, social, political) and cultural contexts (Abraído-Lanza et al., 2006) as well as the fluidity of identity formation (e.g., bicultural identity) that accompanies cultural change (Amaro & de la Torre, 2003).

Transmigration is a parallel concept and has been used in recent years in migration theory to describe immigrants' maintenance of connections between country of origin and destination country and the mutual influences of the social structures and commitments in both places (Basch, Glick Schiller, & Szanton Blanc, 1994; Schiller, Basch, & Blanc-Szanton, 1992).1 This model of transmigration contrasts with previous theories of migration in which it was understood that people were pushed from one location or pulled toward another in a unidirectional and complete fashion, with the sending and receiving locations remaining discrete. Implicit in the earlier model is the idea that people should or would shed one culture (signaled by language, food, festivities, identity) and replace it with another.

As anthropologists of migration have shown, the daily lives of immigrants are enmeshed with concerns based in their home countries. For example, in his description of migration between Chicago and Mexico, DeGenova (1998) showed that “remittances not only provide needed support to the immediate families of migrants … but also finance public works projects … build churches, sponsor festivals and develop soccer stadiums” in Mexico (p. 101). The circulation of money, commodities, human beings, and ideology, he argued, transforms both Mexico and the United States and blurs the distinction between the two (DeGenova, 1998). As a result of this ongoing interconnectedness, Mexican immigrants in the United States are

enmeshed (albeit to varying degrees) in the practical present and the imagined futures of countless agrarian communities across the Mexican countryside. And likewise, the innumerable local concerns of rural Mexico have a palpable presence in the every day lives of migrant workers in Chicago. (DeGenova, 1998, pp. 101-102)

Filipino immigrants to the United States are similarly enmeshed in the lives and practical realities of their home country. Rafael (1997) described how the Marcos regime coined the term balikbayan (back to country) in 1973 and enticed Filipino immigrants in the United States back to the Philippines as tourists with bargain airfares, tax breaks, and other incentives. The immigrants would return to the Philippines with balikbayan boxes, which they felt obliged to bring to their family (Rafael, 1997). Rafael argued that the balikbayan boxes are evidence of immigrant success but also represent the standardization of the Filipino as a hybrid—a mix of both neocolonial immigrant and national Filipino subject.

With this understanding of transculturation and transmigration, we assess the appropriateness of PS to illness and PB of preventive care for Filipinas and Latinas. After a brief description of our study method, we particularly focus on the implications of the powerful contextual processes of transculturation and transmigration for the main assumptions underlying PS and PB: trust in (scientific) information-based messages, trust in the health care system, and a deliberate, conscious decision-making process leading to positive behavior change.

METHOD

This study employed inductive qualitative methods and was designed to describe, from multiple perspectives, the broad web of direct and indirect influences in the lives of immigrant and U.S.-born Filipinas and Latinas living in the San Francisco Bay area (see Pasick, Burke, et al., 2009). We conducted in-person, open-ended interviews with three sets of respondents, all of whom were primary immigrants or first generation U.S. born: key informants (KIs; 5 Latino and 6 Filipino scholars in anthropology, sociology, psychology, theology, or public health and 1 psychiatrist) who were identified based on a combination of professional discipline and insights to their culture, community gate-keepers (GKs; 7 Latino and 7 Filipino social and health service providers and activists, chosen for their direct involvement with and broad knowledge of their community), and lay community women (CWs) of Mexican (15) and Filipino (14) ethnicity who were recruited through professional and community networks to “validate the conceptualization [of cultural processes] against the beliefs of the research community” (Hui & Triandis, 1986) and via snowball methods (Bernard, 1998). Each set of interviews (KIs, GKs, CWs) addressed similar domains and informed each subsequent round of interviews. These interviews were ethnographic in that we did not make the constructs the explicit focus of discussion. Rather, our questions primarily addressed the issues that respondents considered important when thinking about women's lives here in the United States, their health care in general, and, in the final stages of interviews, screening mammography in particular. Gradually, a multidimensional picture emerged of the daily relationships and activities of women in the contexts of family, community, and a wide array of sociopolitical, economic, and historical influences and ultimately the impact these contexts have on health decisions and practices. Although the conversations were wide ranging, they were always brought back to questions of decision making and, specifically, mammography (for list of questions, see Pasick, Burke, et al., 2009). An iterative and multidimensional analytic process led us to identify three major domains of social context: social capital, relational culture, and transculturation (see Figure 1). Finding that processes of cultural change—transculturation and transmigration—infused all the interviews, we analyzed the assumptions and meaning of PS and PB for congruence within this context. Informed consent was obtained from all respondents, and study protocols were reviewed and approved by the Committee on Human Research at the University of California, San Francisco.

RESULTS

Our KIs explained, and our GKs and CWs illustrated through descriptions of daily life from their respective vantage points, that transculturation among U.S. Latinas and Filipinas is a dynamic mixture of past and present, homeland and United States. This mixture was evident in various realms of their lives, including their experiences with the U.S. health care system, public schools, religious and spiritual practices, and health and wellness practices. These converged under five transculturation and transmigration themes: (a) colonialism, (b) immigration dislocation and disorientation, (c) immigration status, (d) discrimination, and (e) therapeutic engagement. We use the following additional abbreviations to indicate type of respondent: KI (key informant), GK (gatekeeper), and CW (community woman). A number (e.g., KI5, GK2, CW4) indicates the specific interview participant, with a 2 preceding the number for Filipina CWs (e.g., CW27).

Colonialism

Our concept of culture not only allows for but also expects the intermingling of influences from long ago with those of the here and now. Transcultural processes may begin with experiences of the United States in the home country, through collective memories of conquest and other historical encounters, the influence of colonialism and neocolonialism on education and health systems, the economy, popular culture, and the stories and remittances immigrants send back home.

Colonialism is a form of cross-cultural contact and cultural change (transculturation) in which direct political, economic, and sociocultural power is imposed by one population, usually a nation-state, on another. The exploitative relationship of colonial rule has complex and profound effects on the colonized, including economic underdevelopment, political instability, religious syncretism, the undervaluing of local mores and practices, and internalized oppression.

So you have an entire generation of Filipinos that were raised to believe that we are the little brown sisters, because the narrative of Manifest Destiny. And benevolent assimilation is very damaging … the psychic and epistemic consequences of this colonial relationship, it's what really defines the Filipino experience. At least for this generation. (KI4)

A history of colonialism (and neocolonialism, where power is wielded indirectly rather than through direct rule) is familiar to many immigrants and people of color in the United States. The Filipina anthropologist Espiritu (2003) wrote, “The relationship between the Philippines and the United States has its origins in a history of conquest, occupation and exploitation. A study of Filipino migration to the United States must begin with this history” (p. 1). Like the Philippines, Latin America was first colonized by the Spanish and then came under U.S. influence. Although the Philippines were directly colonized, Latinos in the United States are primarily from countries where the United States has wielded extensive influence, especially political and economic influence, often characterized as neocolonial. For Filipinas as well as Latinas, as this KI explained, (neo)colonization imbues a “less than” status.

Part of the psychology of being colonized is knowing deep within your soul that you're not really inferior … but you've been told, and you've been oppressed and your life and economic and social conditions have been structured so that it really almost convinces you that maybe you are indeed inferior. (KI4)

Experiences of colonization are integral to the challenges of immigration and discrimination experiences that may lead to unwillingness to encounter the health care system and distrust of those who operate it.

I'm trying to think of other things that might prevent desire to access the system … but I think the big thing is really just being intimidated because you don't have the knowledge because you don't have the connection, you don't have the confidence, and perhaps the feeling of, you know feeling inferior is part of it. Of not being good enough and maybe that's even the biggest problem. (KI4)

Immigration: Dislocation, Disorientation, and Disruption

Immigration involves profound experiences of dislocation, disorientation, and social isolation. Immigration of a colonized people both compounds and is compounded by such experiences. Experiences of dislocation, disorientation, and social isolation can limit knowledge of and access to the health care system and, in conjunction with the struggles created by colonialism, can create deep senses of illegitimacy, not belonging, and not being welcomed in many spheres of life, including health care.

Even in just the most basic ways—like you get on the bus and people will—people will contort into every position to not touch a stranger. … And I think there's that real loss of physical contact and just kind of feeling always being “off” on social cues and just not knowing what to do when you meet someone. (GK10)

This sense of being “off” on social cues reflects outwardly subtle but profoundly meaningful cultural differences that can be hard to name and therefore even harder to negotiate and that can discourage people from dealing with a new and potentially unwelcoming medical system.

[We] land in San Francisco … we don't even know the subway system here … there's no such thing in the Philippines … to even master how to get around. … And we're talking about [the] health field … where do you find doctors that could understand you? … In the Philippines, we were all schooled in the English language … but … over here … the accent is so different … so, we're not really being understood. (KI8)

“The reality of the accent,” as she put it, was an abrupt and unexpected recognition of difference. Although many Filipinos speak English—it was made a national language as a result of U.S. colonization—communication can still be difficult.

And you're trying to speaking in English, and you cannot do it fast enough, you can't do it simultaneously to [mentally translate], and you're surrounded by people that talk very fast … and talk very loudly and they're taller than you [laughter] … so I think part of our discomfort with the system is the overwhelming Whiteness of it and also the influence of norms, how different they are. (KI4)

As a result of such differences and discomfort, some of the women in our study chose to get their medical care in their home country. Travel back and forth and the maintenance of relationships in both countries (transmigration) made accessing care in the home country possible, and in some cases preferable.

Over there, they have access to health insurance and over here, they don't … they have in some cases, but they'd rather go over there. And maybe not only the access but the language … they will be more comfortable going to a doctor that speaks their own language. Or, if they have to pay, I think it's almost cheaper. Services are cheaper than here. I also have talked to some women that are from El Salvador and she … this woman was telling me, “Well, I go to El Salvador every year and I get all my screening over there.” Or some women just go to Tijuana. (GK1)

For one woman who routinely received care when visiting family in Mexico, the benefits of seeking mammography screening in the United States were not sufficient in light of the costs of learning the system and her lack of access. Her long-term relationship with her doctor in Mexico, along with the familiarity and comfort of getting care there, might have encouraged her to seek a mammogram there where she also obtained regular Pap tests. Another Latina woman, however, explained that, over time, her fear and intimidation gave way to confidence and, with that, the ability to seek health care in the United States and advocate for herself (Burke, Bird, et al., 2009).

An unfamiliar situation, activity, person, setting, or, in more general terms, context gives rise to great fear or anxiety. Two KIs commented, “Not knowing what to expect is a terrifying thing” (KI7) and “Familiarity is a very important part in making the Filipino patient comfortable in any clinical situation. It's not a familiar procedure … machines, gas, medications were not in hinterland Philippines … medications are seen suspiciously … they'd rather go for their arbularyos (healers) with herbal therapies and prayers” (KI8).

Lack of familiarity also affects receptivity to health information. To be effective, the source must be familiar to the person being instructed and the information must resonate with their values. Two participants explained,

Because, if they're not familiar [with the system] … even if you tell them it's for the good of the family, it won't fly … and for somebody who … doesn't even know it can be done … they give up easily. (KI8)

The information has to be familiar … somewhere, you know, they need to be able to recognize it … decode stuff that you're throwing at them. It has to be proximate … real close in to their life space. (KI9)

Thus, the legitimacy or validity—and, hence, the influence—of information provided in or by this unwelcoming context may be drowned out by unfamiliarity. As Pasick, Barker, et al. (2009) note, “The messenger can be far more important than the message” (p. 102S).

Immigration Status

The literature (e.g., Echeverria & Carrasquillo, 2006) and our findings document how the political and legal distinctions made with regard to immigrants in the United States—as legal or illegal, documented or undocumented residents—affect health-seeking behavior. One undocumented Filipina described, for example, the fear of being reported to the immigration authorities and being deported and the sense of shame and inferiority that comes from constantly having to respond to questions about one's immigration status. At times, this outweighed the perception of benefits of a recommended health behavior.

Interviewer: So is the reason why you don't go to the doctor because … [pause] … you don't have time? Are there other reasons why?

Participant: Because in the first place, I don't have insurance. They will ask, “Your—do you have insurance? Do you have, are you le– [legal].” Sometimes they ask your Social Security [number] and everything. And I don't have that. So I, I know some hospital will refuse to check you. So I'm afraid of that. …

Interviewer: If, if someone were to tell you that, “Oh, you can go and get a mammogram,” in the next 12 months, would you go?

Participant: Yeah. As long as they will not ask lots of question about my, you know … [immigration status]. Yeah. I, I love to, because … that's for, you know … for my health. (CW213)

This woman perceived the benefits of mammography for her health but not in isolation from her social context—her immigration status, her understanding of how that affected her access to health care, and its implicit impact on her family.

Discrimination: “And Then You Deal With Discrimination … That's Real.” (KI8)

Closely connected to immigration status, but also independent of it, women in our study recounted disturbing tales of their vulnerability to discrimination and abuse as immigrants, ethnic minorities, non-English speakers, or those unfamiliar with the medical system. In various cases, medical providers were revealed as being ignorant, insensitive, and disrespectful.

I was desperate for them to give [my daughter] something for the pain, that he would say something, that he would produce a solution for that pain. And the conversation was, “Oh, Brenda. Why Brenda and not Lupe, Maria? … Where are you from?” I told him that we were from Mexico. … And he continued “Brenda? And why not Lupe or Maria or Juanita?” That is what the doctor said to me. I was desperate about my daughter and he was talking about why I hadn't named my daughter another name. (CW5)

Several women told stories that revealed their vulnerability as women to sexual abuse and manipulation by health care providers.

The doctor asked me to lie down on the table. … He wanted me to take off my clothes, and he locked the door from the inside. So I told him that I had to come back with someone because that did not seem right to me. … I had to get out of there, and it was a horrible experience because I think that he wanted to sexually abuse me. (CW9)

Women also reported discrimination on the basis of insurance status and income. One uninsured recent immigrant felt she was treated disrespectfully—not even given the information about her diagnosis or referred for affordable care—because her doctor made the assumption she could not pay for the treatment she needed. The doctor told her,

“I've already found your problem. But you can't pay. You can't pay. The medicine is very expensive and you can't pay.” I felt so bad. I left that office crying, crying, crying. I never went back to see that doctor. … He didn't tell me or guide me. … There are so many hospitals. … He could have said, “I cannot help you but you can go to such and such a place.” Now I know that there are other places, but when I first got here I didn't know. (CW13)

Fortunately, this woman figured out how to get care without the help of this physician, but it is likely that others in such situations do not. Thus, even women who feel susceptible to breast cancer and/or understand the potential benefits of a screening mammogram may not be getting mammograms to avoid feeling belittled or mistreated.

Therapeutic Engagement

Known as “medical pluralism” in medical anthropology, the combining of different traditions of therapeutic practices by one person or in one system is common through-out the world. Ideas and practices that combine elements of biomedicine and traditional or alternative health practices took many forms among our participants. Some respondents mentioned practices that were explicitly connected to their religious and spiritual identity, whereas others were based on home country practices (e.g., taking herbs or drinking teas) or complementary and alternative practices common in the San Francisco Bay area. In the context of this variety of healing practices, the PB of biomedicine is limited, good for some things, but not all. One participant, in discussing her expectations of doctors, articulated a division of labor between biomedicine and alternative practices: going to the doctor is good for diagnosis but not necessarily for treatment.

It's important to get [biomedical] tests and exams, to know what you have. If you don't want to take the medicine that the doctor prescribes, you can help yourself. … Natural medicine helps to fortify the parts of your body that are deteriorating. The doctor's medicine is killing the virus or the infection. They do their jobs differently. (CW11)

The mixed use of biomedical and alternative healing practices among our participants suggests that perceptions of susceptibility to illness and benefits of biomedical prevention practices such as mammography are complex manifestations of transcultural processes. The context of colonialism and immigration is, for many of our participants, woven tightly with a religious or spiritual orientation to the world, profoundly influencing the meanings of illness, life, death, and one's relationship to these processes. The integration of religious and spiritual orientations and practices that involved healing infused highly variable meanings into perceptions of susceptibility and benefits among our participants. Although biomedicine typically focuses on the individual body as the locus of disease (and hence locates susceptibility and benefits in behaviors that affect the body), other worldviews frame health and illness in terms of more transcendent or metaphysical phenomena such as balance (hot-cold, yin-yang) and social harmony (G. Becker, 2003; Kleinman, 1981). People with such orientations might locate the cause of illness (and hence susceptibility to illness) in relationships that are out of balance or disharmonious (see Pasick, Barker, et al., 2009) or in retribution for bad deeds or immoral behavior. Religious and spiritual orientations among our respondents—in part beliefs and in part an unconscious way of understanding the world—were not usually exclusive of beliefs in biomedicine. Recalling her reaction to being diagnosed with breast cancer, one Mexican American woman told us,

I'm a spiritual person. I'm a strong believer in a higher power, and in prayer. And I knew that I had no control. That was out of my hands. I was in the hands of good doctors, but they were also in the hands of a greater power. You know, of the Teacher, so … I gave in. I said, “I'm in your hands,” and the only thing I could do was have a positive attitude and take care of myself. (CW4)

In contrast to the “fatalism” so often discussed in public health and social science literature, this woman's religious orientation incorporated and was consistent with her use of biomedical interventions. Some of our KIs regarded the construct of “fatalism” as flawed precisely because it fails to account for structural circumstances such as poverty and colonialism.

Somehow the idea is that Latinos can't think about tomorrow because you know, God gave us today and that's it. … I think that the experiences of being poor in Latin America don't give you much option in life … if you're well off, you have access to good medical care, if you don't—the other 90%—you're pretty much gonna be a fatalist [laughs]. (KI2)

The belief in “God's will”—as it appears on a survey—might reflect a lack of control over health caused by scant resources or minimal access to health care. Under such conditions, “folk” or home remedies (e.g., chicken soup and herbal tea) or denial are viable, practical, and even protective options (Kagawa-Singer & Kassim-Lakha, 2003). Another KI explained how the context of colonialism contributed to “fatalism”:

There is a negative connotation attached to fatalism, and the Tagalog word is bahala na, but the anthropologists and social psychologists that have studied this, they said that this attitude is really a product of again, colonization. When you know that you are not in control of your circumstances, and so you kind of do everything you can and then you ask God to do the rest. Bahala na: you know, it's up to God. But whatever outcome he wants. I've already done what I need to do and there's nothing more I can do before I surrender it. (KI4)

Fatalism is giving up without really trying, but these respondents make clear that is not what is happening here. Rather the exact opposite occurs: “You kind of do every-thing you can [within your often limited means] and then you ask God to do the rest.” This Filipina KI also suggested that the acceptance of death as “just a part of life” put a different spin on medicine than in the United States.

So it's more about faith, faith that there is something bigger than medicine, there is some-thing bigger than you know, uh, surgery, but that also comes from the fact that we will accept death, uh, very well. That death is just a part of life. So it's not a death denying culture as much as it is in the U.S. (KI4)

Thus, understanding the combination of the historical context of colonialism, the meaning of poverty in everyday life, and culturally specific ideas about control, faith, and death affords quite a different reality than what is often described negatively and simply as fatalism. These observations are consistent with those of Trostle (2005), who wrote,

Anthropologists have long said that non-Western cultures explain misfortune partly through magic and witchcraft. Anthropologist E. E. Evans-Pritchard wrote in his classic book Witchcraft, Oracles and Magic among the Azande that his African village informants were perfectly capable of explaining that a raised granary collapsed because termites had eaten through the supports (Evans-Pritchard, 1937). But witchcraft explained why that particular granary collapsed just when that particular individual was seated underneath it enjoying the shade. (p. 163)

Biomedicine that diagnoses a woman's breast cancer is equivalent to talking about termites; spiritual belief, however, answers her questions about “Why me?” “Why now?” “Why this cancer?” just as it explains who was affected and why when a granary collapsed.

DISCUSSION

Our data raise significant questions about the universality of certain central assumptions embedded in health behavior theories; namely, that people will take action to prevent, to screen for, or to control illness if they (a) believe that they are susceptible to that illness, (b) believe that by following a recommended health action (e.g., cancer screening), they will reduce their susceptibility to or the severity of the illness, and (c) believe that the benefits of taking the recommended action outweigh the perceived barriers or costs for doing so (Janz et al., 1995, p. 47). Even more important, our findings raise significant doubts about two assumptions inherent to the constructs of PS and PB: first, that people trust that the health care system will effectively serve them, as demonstrated under the colonialism, immigration, and discrimination themes; and second, that people believe in and trust scientific principles and technical biomedical knowledge exclusively, over and above other healing beliefs and practices, as demonstrated by the therapeutic engagement theme.

In contrast to these assumptions, we conclude that beliefs about susceptibility to illness and benefits of preventive care are less significant or even antithetical in the face of the meanings of health and illness we have described. For the U.S.-born and immigrant Filipinas and Latinas in our study, the transcultural domains of colonialism, immigration, discrimination, and therapeutic engagement are key components of their social context that inform their everyday meanings of health and illness.

The history of colonialism, immigration status, and present-day discrimination shapes the worldviews and daily lives (including health practices) of the women in our study. They evaluate (consciously or not) the benefits of cancer screening such as mammography not only in relation to susceptibility but also and often more important in relation to social and legal structures (e.g., colonialism or citizenship) that shape experiences of immigration and discrimination. Even if a woman feels susceptible to breast cancer, the benefits of screening mammography may not (a) outweigh the fear of being deported if her undocumented migration status is discovered, (b) outweigh the cost of the humiliation and anger that result from the discrimination or plain confusion and incomprehension so often experienced at a doctor's office, or (c) be worth overcoming expectations that the screening or treatment will involve medical experimentation or other abuses of power.

Furthermore, our participants drew on traditional and alternative healing practices (some based in spiritual orientations) and biomedicine in a process of transculturation that influenced their perceptions of susceptibility to illness and their perceptions of benefits of biomedical interventions such as mammography. The varied understandings of how disease affects the body, and the body's susceptibility to illness, affect how women perceive the benefits of prevention and intervention measures. Our data demonstrate only a small part of the range of meanings and perceptions of the body and its susceptibility to cancer that relate to transculturation. Unconscious domains of social context (Burke, Joseph, et al., 2009) can powerfully shape perceptions of susceptibility to illness and benefits of preventive behaviors—and likely cannot be addressed by efforts to correct “misconceptions” with biomedical information alone. Furthermore, when asked why they have not gotten a mammogram, it is quite easy to point to lack of insurance, to claim that it is not needed “at my age” or “only if I find a lump.” It is a much greater challenge to capture in surveys the underlying distrust or therapeutic orientation that we describe here.

The framework of transculturation is relevant for forms of cultural contact and change that do not involve migration, and thus some of our findings may be valid for Anglo Americans, other immigrant groups, and African, Asian, Latino, and Native Americans. In certain contexts, for example, African Americans may negotiate “White America,” and people who have grown up in poverty may encounter unfamiliar practices, assumptions, and mores that they must negotiate when they enter the middle class (e.g., Bourgois, 2003).

Our findings suggest that the realities of transculturation and transmigration influence and shape perceptions of susceptibility to illness and of the benefits of biomedical health practices such as screening mammography, thus pointing out limitations of the constructs of PB and PS. The meaning of concepts such as susceptibility and benefits, like those of health and illness, are not universal and hence should not be uniformly and unquestioningly applied across diverse groups.

IMPLICATIONS FOR PRACTICE

Our study indicates that theorists, practitioners, and interventionists should look beyond longstanding theories and the interventions that have emanated from cognition and individual-focused understandings of health behavior to take into account the social dislocation, discrimination, and legal status issues that are often part of being an immigrant or of recent immigrant ancestry in this country.

Implications for Theorists

Our findings suggest that it is critical for theorists to address the complexity of social life and health behavior in their models and frameworks for assessing the effects of PB and PS on cancer screening behavior. This may require modification or expansion of these constructs to include dimensions of social and cultural context of diverse populations not previously considered. Further study will be required to assess how such measures would be operationalized and measured without losing the complexity identified in the present article and other articles in this volume.

Implications for Practitioners

It is fundamental to welcome newcomers via community health workers who can forge trusting relationships, as illustrated by the delivery of care in community health centers (Frick & Regan, 2001). Within these contexts, familiarity with U.S. health care practices and systems is not assumed, and communication of caring and mutual understanding can serve as a highly effective basis for invitations to attend to cancer screening (Farquhar, Michael, & Wiggins, 2005). In addition, community-based organizations (e.g., faith organizations) should be integrally involved in supporting and delivering health promotion and should be formally connected to the health care system via trusted community workers and community leaders. Such organizations and the people who staff them are likely to share and/or understand the social context of immigration—the history of colonialism, immigration status, and discrimination and the role of religious and spiritual worldviews in therapeutic practices. In these ways, breast cancer education can better account for and incorporate the social context of immigration.

Implications for Interventionists

Clearly, information-based interventions, which may be effective for some population segments, should not compose the sole approach to screening promotion for women of immigrant origins. Following the lead in tobacco, mammography promotion interventions should go beyond a presentation of ostensibly neutral facts (Balbach, 2006). It is important for those who deliver health interventions to have an understanding of their clients beyond the particular health behavior (e.g., not just as smokers or people who are overweight or behind on screenings), but as people with complex life stories and circumstances that affect the meaning of health and health-related behavior.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by the National Cancer Institute (Grant RO1CA81816, R. Pasick, principal investigator).

This supplement was supported by an educational grant from the National Cancer Institute, No. HHSN261200900383P.

Footnotes

The state of living simultaneously enmeshed in life in two or more nations is referred to as transnationalism in this literature.

Contributor Information

Galen Joseph, Galen Joseph, Department of Anthropology, History, and Social Medicine, University of California, San Francisco..

Nancy J. Burke, Nancy J. Burke, Helen Diller Family Comprehensive Cancer Center and Department of Anthropology, History, and Social Medicine, University of California, San Francisco..

Noe Tuason, Noe Tuason, Helen Diller Family Comprehensive Cancer Center, University of California, San Francisco..

Judith C. Barker, Judith C. Barker, Department of Anthropology, History, and Social Medicine, University of California, San Francisco..

Rena J. Pasick, Rena J. Pasick, Helen Diller Family Comprehensive Cancer Center, University of California, San Francisco..

References

- Abraído-Lanza AF, Armbrister A, Flórez KR, Aguirre A. Toward a theory-driven model of acculturation in public health research. American Journal of Public Health. 2006;96:1342–1346. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.064980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen I. The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes. 1991;50:179–211. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen I. The social psychology of decision making. In: Higgins ET, Kruglanski AW, editors. Social psychology: Handbook of basic principles. Guilford Press; New York: 1996. pp. 297–328. [Google Scholar]

- Amaro H, de la Torre A. Public health needs and scientific opportunities in research on Latinas. American Journal of Public Health. 2003;92:525–529. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.4.525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashing-Giwa K. Health behavior change models and their socio-cultural relevance for breast cancer screening in African American women. Women's Health. 1999;28(4):53–71. doi: 10.1300/J013v28n04_04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balbach ED. How the health belief model helps the tobacco industry: Individuals, choice, and “information. Tobacco Control. 2006;15(Suppl. 4):iv–37. doi: 10.1136/tc.2005.012997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Prentice Hall; Englewood Cliffs, NJ: 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Basch L, Glick Schiller N, Szanton Blanc C. Nations unbound: Transnational projects, postcolonial predicaments, and deterritorialized nation-states. Gordon & Breach; Langhorne, PA: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Bay Area Census San Francisco Bay area. 2000 Retrieved from http://www.bayareacensus.ca.gov/bayarea.htm.

- Becker G. Cultural expressions of bodily awareness among chronically ill Filipino Americans. Annals of Family Medicine. 2003;1:113–118. doi: 10.1370/afm.39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker G, Newsom E. Socioeconomic status and dissatisfaction with health care among chronically ill African Americans. American Journal of Public Health. 2003;93:742–748. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.5.742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker MH, editor. The health belief model and personal health behavior. Health Education Monographs. 1974;2:324–508. [Google Scholar]

- Bernard HR. Handbook of methods in cultural anthropology. Altamira; Walnut Creek, CA: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu P. The logic of practice. Stanford University Press; Stanford, CA: 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Bourgois P. In search of respect: Selling crack in el barrio. Cambridge University Press; New York: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Burke NJ, Bird JA, Clarke MA, Rakowski W, Guerra C, Barker JC, et al. Social and cultural meanings of self-efficacy. Health Education & Behavior. 2009;36(Suppl. 1):111S–128S. doi: 10.1177/1090198109338916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke NJ, Joseph G, Pasick RJ, Barker JC. Theorizing social context: Rethinking behavioral theory. Health Education & Behavior. 2009;36(Suppl. 1):55S–70S. doi: 10.1177/1090198109335338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Champion VL, Huster G. Effect of interventions on stage of mammography adoption. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 1995;18:169–187. doi: 10.1007/BF01857868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Champion VL, Scott CR. Reliability and validity of breast cancer screening belief scales in African American women. Nursing Research. 1997;46(6):331–337. doi: 10.1097/00006199-199711000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coronil F. Introduction. In: Ortiz F, editor. Cuban counterpoint: Tobacco and sugar. Duke University Press; Durham, NC: 1995. pp. ix–lvi. [Google Scholar]

- Decruyenaere M, Evers-Kiebooms G, Welkenhuysen M, Denayer L, Claes E. Cognitive representations of breast cancer, emotional distress and preventive health behaviour: A theoretical perspective. Psycho-Oncology. 2000;9(6):528–536. doi: 10.1002/1099-1611(200011/12)9:6<528::aid-pon486>3.0.co;2-#. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeGenova N. Race, space, and the reinvention of Latin America in Mexican Chicago. Latin American Perspectives. 1998;25(5):87–116. [Google Scholar]

- Duke SS, Gordon-Sosby K, Reynolds KD, Gram IT. A study of breast cancer detection practices and beliefs in Black women attending public health clinics. Health Education Research. 1994;9:331–342. doi: 10.1093/her/9.3.331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Echeverria SE, Carrasquillo O. The roles of citizenship status, acculturation, and health insurance in breast and cervical cancer screening among immigrant women. Medical Care. 2006;44(8):788–792. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000215863.24214.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emmons KM, Stoddard AM, Fletcher R, Gutheil C, Suarez EG, Lobb R, et al. Cancer prevention among working class, multiethnic adults: Results of the Healthy Directions-Health Centers Study. American Journal of Public Health. 2005;95:1200–1205. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.038695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espiritu YL. Home bound: Filipino American lives across cultures, communities and countries. University of California Press; Berkeley: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Farquhar SA, Michael YL, Wiggins N. Building on leadership and social capital to create change in 2 urban communities. American Journal of Public Health. 2005;95:596–601. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.048280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fishbein M, Ajzen I. Belief, attitude, intention, and behavior: An introduction to the theory of research. Addison-Wesley; Reading, MA: 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Frick KD, Regan J. Whether and where community health centers users obtain screening services. Journal of Healthcare for the Poor and Underserved. 2001;12(4):429–445. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2010.0787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geertz C. The interpretation of cultures. Basic Books; New York: 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Glanz K, Rimer BK, Lems F. Health behavior and health education. 3rd ed. John Wiley; New York: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Helman C. Culture, health & illness. 5th ed. Trans-Atlantic; Philadelphia: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Hiatt RA, Pasick RJ, Perez-Stable EJ, McPhee S, Engelstad L, Lee M, et al. Pathways to early cancer detection in the multiethnic population of the San Francisco Bay area. Health Education Quarterly. 1996;23(S):S10–S27. [Google Scholar]

- Hui CH, Triandis HC. Individualism–collectivism: A study of cross-cultural researchers. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology. 1986;17(2):225–248. [Google Scholar]

- Hunt LM, Scheider S, Comer B. Should acculturation be a variable in health research? A critical review of research on U.S. Hispanics. Social Science & Medicine. 2004;59:973–986. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2003.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janz N, Champion V, Stecher V. The health belief model in theory at a glance: A guide for health promotion practice (NIH 95-3896) National Institute of Health, National Cancer Institute; Bethesda, MD: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Kagawa-Singer M. Improving the validity and generalizability of studies with under-served U.S. populations expanding the research paradigm. Annals of Epidemiology. 2000;10(8 Suppl.):S92–S103. doi: 10.1016/s1047-2797(00)00192-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kagawa-Singer M, Kassim-Lakha S. A strategy to reduce cross-cultural miscom-munication and increase the likelihood of improving health outcomes. Academic Medicine. 2003;78(6):577–587. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200306000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kagawa-Singer M, Pourat N, Breen N, Coughlin S, Abend McLean T, McNeel TS, et al. Breast and cervical cancer screening rates of subgroups of Asian American women in California. Medical Care Research and Review. 2007;64(6):706–730. doi: 10.1177/1077558707304638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katapodi MC, Lee KA, Facione NC, Dodd MJ. Predictors of perceived breast cancer risk and the relation between perceived risk and breast cancer screening: A meta-analytic review. Preventive Medicine. 2004;38:388–402. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2003.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleinman A. Patients and healers in the context of culture. University of California Press; Berkeley: 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Krumeich A, Weijts W, Reddy P, Meijer-Weitz A. The benefits of anthropological approaches for health promotion research and practice. Health Education Research. 2001;16:121–130. doi: 10.1093/her/16.2.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambert H, McKevitt C. Anthropology in health research: From qualitative methods to multidisciplinarity. BMJ. 2002;325(7357):210–213. doi: 10.1136/bmj.325.7357.210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ortiz F. Cuban counterpoint: Tobacco and sugar. Duke University Press; Durham, NC: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Pasick RJ, Barker JC, Otero-Sabogal R, Burke NJ, Joseph G, Guerra C. Intention, subjective norms, and cancer screening in the context of relational culture. Health Education & Behavior. 2009;36(Suppl. 1):91S–110S. doi: 10.1177/1090198109338919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasick RJ, Burke N. A critical review of theory in breast cancer screening promotion across cultures. Annual Review of Public Health. 2008;29:351–368. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.29.020907.143420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasick RJ, Burke NJ, Barker JC, Joseph G, Bird JA, Otero-Sabogal R, et al. Behavioral theory in a diverse society: Like a compass on Mars. Health Education & Behavior. 2009;36(Suppl. 1):11S–35S. doi: 10.1177/1090198109338917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pratt ML. Imperial eyes: Travel writing and transculturation. Routledge; New York: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Prochaska JO. Systems of psychotherapy: A transtheoretical analysis. Brooks-Cole; Pacific Grove, CA: 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Rafael V. Your grief is our gossip: Overseas Filipinos and other spectral presences. Public Culture. 1997;9:267–291. [Google Scholar]

- Resnicow K, Page SE. Embracing chaos and complexity: A quantum change for public health. American Journal of Public Health. 2008;98:1382–1389. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.129460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson J, Marks G, Solis J, Collins L, Virba L, Hisserich J. Frequency and adequacy of breast cancer screening among elderly Hispanic women. Preventive Medicine. 1987;16:761–774. doi: 10.1016/0091-7435(87)90016-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenstock IM. Historical origins of the health belief model. Health Education Monograph. 1974;2:328–335. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenstock IM. Why people use health services. Milbank Quarterly. 2005;83:4. [Google Scholar]

- Schiller NG, Basch L, Blanc-Szanton C. Transnationalism: A new analytic frame-work for understanding migration. Annals of New York Academy of Sciences. 1992;645:1–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1992.tb33484.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slovic P, Finucane ML, Peters E, MacGregor DG. Risk as analysis and risk as feelings: Some thoughts about affect, reason, risk, and rationality. Risk Analysis. 2004;24(2):311–322. doi: 10.1111/j.0272-4332.2004.00433.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart SL, Rakowski W, Pasick RJ. Behavioral constructs and mammography in five ethnic groups. Health Education & Behavior. 2009;36(Suppl. 1):36S–54S. doi: 10.1177/1090198109338918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trostle JA. Epidemiology and culture. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge, UK: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Vernon S. Risk perception and risk communication for cancer screening behaviors: A review. Journal of the National Cancer Institute Monographs. 1999;25:101–119. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jncimonographs.a024184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu T, Yu M. Reliability and validity of mammography screening beliefs question-naire among Chinese American women. Cancer Nursing. 2003;26(2):131–142. doi: 10.1097/00002820-200304000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yarbrough SS, Braden CJ. Utility of health belief model as a guide for explaining or predicting breast cancer screening behaviours. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2001;33(5):677–688. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2001.01699.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]