Abstract

Among 224 African American adolescents (mean age 14), the associations between interracial, intraracial contact and school-level diversity on changes in racial identity over a 3-year period were examined. Youths were determined to be diffused, foreclosed, moratorium or achieved; and change or stability in identity status was examined. Contact with Black students, Black friends, and White friends predicted change in identity status. Further, in racially diverse schools, more Black friends were associated with identity stability. Students reporting low contact with Black students in racially diverse schools were more likely to report identity change if they had few Black friends. Students reporting high contact with Blacks in predominately White schools, identity was less likely to change for students with fewer White friends.

Intergroup contact theory suggests that under certain conditions, the more intergroup contact individuals have, the more likely they are to feel positive towards out-group members (Pettigrew, 1998). Indeed, research has shown that positive interactions with different-race individuals have been associated with outcomes such as reduction in prejudice (Molina & Wittig, 2006), increases in a sense of common identity (Nier, et al., 2001), and personal closeness (Tropp, 2007). In a meta-analytic review of studies that have examined the contact hypothesis, Pettigrew & Tropp (2006) reported that intergroup contact has a positive impact on reducing prejudice for members of the general out-group and not just specific members with whom an individual has had interactions. However, as Pettigrew writes (1998), “optimal intergroup contact provides insight about ingroups as well as outgroups” (pg. 72). Indeed, research suggests that in-group and out-group contact influence the development of racial identity (Alba & Nee, 2003; Portes & Rumbaut, 2001). The current study will address two gaps in the current literature on the effects of contact on adolescent development. First, the study will consider the influences of both intergroup and intragroup peer contact and friendships on changes in youth’s feelings about their own racial identity over time. Finally, this study will consider the opportunities that youth have for interracial and intraracial contact and friendships by examining how contact interact with school-level diversity to influence racial identity changes.

Racial Identity Development

Many scholars have discussed the importance of identity exploration and construction during adolescence (Erikson, 1968; Marcia, 1980; Phinney, 1993). Indeed, identity status models outline how the combination of identity exploration and commitment change as adolescents learn more about their racial group. Specifically, Marcia (1966) and Phinney (1992) offer a model of identity development where adolescents can be in one of four statuses: neither explored nor committed to their identity (diffused), committed to an identity without exploring (foreclosed), explored but have not committed (moratorium), or have both explored and committed to an identity (achieved). Inherent in this model is a pattern of linear progression from less to more advanced stages. Recently empirical work has lent some support to this theory finding that adolescents were more likely to report being in the less advanced statuses as compared to older adults (Yip, Seaton, & Sellers, 2006). Other research finds that even from one year to the next, adolescents report moving from one identity status to another (Seaton, Scottham, & Sellers, 2006). Thus, racial identity appears to be changing for minority youth during the adolescent period, but the empirical literature is less clear about antecedents to change in racial identity status.

Intergroup Contact and Racial Identity

There are many possibilities for what might precede changes in identity. One such consideration is social interactions with other-race peers. In one of the few studies examining the association between racial identity and intergroup contact, Lee and his colleagues found that among Koreans living in China, those who reported more social interactions with Chinese reported lower levels of ethnic identity when discrimination was frequent (Lee, Noh, Yoo, & Doh, 2007). In a study of African, Asian and European American adolescents, Hamm (2000) found that only for European Americans did having cross-race friendships have an association with ethnic identity. In particular, it was observed that having a cross-race friendship was associated with higher scores on importance and positive regard for one’s ethnicity. In a study of Latino adolescents, attending predominately non-Latino school was associated with stronger ethnic identity (Umana-Taylor, 2004). Together, these studies suggest intergroup contact may have important implications for identity development. However, since none of these studies employed longitudinal data, the nature of the relationship between contact and racial identity is unclear.

Intragroup Contact and Racial Identity

Although the contact hypothesis focuses primarily on the effects of intergroup contact, research has also examined the very important influence of intragroup interactions for youth development. For example, in a study of African American adolescents, Rowley and colleagues (Rowley, Burchinal, Roberts, & Zeisel, 2008) found that same-race friendships were associated with increased reports of racial discrimination. Although same-race friends were not linked to racial identity explicitly in that study, recent research suggests that discrimination is a form of social interaction that may then lead to the exploration of and commitment to one’s identity (Seaton, Yip, & Sellers, 2009). Specifically, theory suggests that experiences of racial discrimination may serve as encounters that cause individuals to rethink the role of race in their lives; a process that can occur anywhere in the developmental lifespan (Cross & Fhagen-Smith, 2001). In research that considered ethnic identity as an outcome, researchers found that having a stronger sense of ethnic identification was associated with more in-group peer interaction (Phinney, Romero, Nava, & Huang, 2001). In retrospective research on Black college students who attending predominately White high schools, it was observed that having positive same-race peer relationships was associated with more resolution in racial identity formation (Tatum, 2004). Therefore, it seems that having more same-race friends may be associated with changes in racial identity status over time. Taken together, the current empirical literature suggests that both intergroup and intragroup contact could be related to changes in racial identity.

School Diversity

Implicitly, intergroup contact theory suggests that individuals should have opportunity to interact with out-group members in everyday contexts. Indeed, scholars have discussed the importance of opportunity for contact in the context of macro-level variables such as diversity, in their discussion of intergroup contact theory (de Souza Briggs, 2007; Pettigrew, 2006). Since the primary context in which adolescents have contact with peers is school, this study considers school-level diversity as an indicator of the opportunities that youths have to interact with same- and different-race peers. Schools that are characterized by high diversity afford youths increased opportunity to interact with same- and different-race peers. Schools with low diversity, however, may only offer youths the opportunity to interact with same- or different-race peers, but not both. Therefore, the current study considers school-level diversity as an important third variable to consider in examining the association between contact and changes in racial identity.

Furthermore, even with the opportunity to interact with same- and different-race peers, adolescents may not actually interact with them. For one, there may be institutional barriers; for example, classes may be organized in a manner that is not conducive to interactions between students in different academic tracks (Kubitschek & Hallinan, 1998; Mickelson & Heath, 1999). Specifically, research suggests that academic tracks often differ by race (Schwarzwald & Cohen, 1982). Beyond academic divisions, in social interactions, it has also been observed that youths may self-segregate and befriend only same-race peers (Tatum, 1997). For example, a study of Dutch adolescents found that despite attending diverse schools where at least half of the students were not Dutch, 16% of the Dutch students reported having no contact with non-Dutch peers (Masson & Verkuyten, 1993). Outside of school, where students presumably have more choice about whether or not to engage in intergroup interactions, 45% of students reported little or no cross-ethnic interactions. In this same study, students reporting a more positive attitude about their racial group also reported less intergroup contact. In a study of Black and White 4th grade students, researchers found that students attending an integrated school were much more likely to mention race and ethnicity in discussions about self-concept than children attending predominately Black or White schools (Dutton, Singer, & Devlin, 1998). As such, it seems important to not only consider youths’ opportunities to interact with same- and different-race peers, but also behavioral indicators of whether or not youth actually make friends with same- and different-race peers.

Friendships

Therefore, another approach to evaluating the contact hypothesis (Pettigrew, 2007) includes research in the area of cross-race friendships. As an operationalization of the contact hypothesis, studies of cross-race friendships have lent support to the basic tenets of the theory. For example, research examining school-level racial diversity on friendship choices among high school students finds that the higher the proportion of same-race peers in a student’s school, the more likely he or she will be to have same-race friends (Kao & Joyner, 2006; Kao & Vaquera, 2006). Similarly, other research suggests that cross-race friendship are more likely in more racially diverse schools (Quillian & Campbell, 2003). Patterns for ethnicity are analogous, such that attending a school with more same-ethnicity peers also makes it more likely that students will report having more same-ethnicity friends (Kao & Joyner, 2006).

From a probabilistic point of view, it seems logical that the more opportunity one has to form cross-race friendships, the more likely the friendships will occur. However, research suggests that actual behavior patterns are less predictable. Research on Black and White school children has found that students in integrated and predominately White schools were more likely to report having cross-race friendships (Dutton, et al., 1998). In a study of Black and White students attending an integrated junior high school, most students reporting having a close other-race friend; however, only 28% of the sample reported having interactions with other-race friends off campus (DuBois & Hirsch, 1990). At the same time, research on adolescents has observed when one’s group represents a small minority in an otherwise homogenous school, the probability of same-race friendship increases (Quillian & Campbell, 2003). In a study with adults, using multilevel models that estimated the probability of establishing cross-race friendships given the relative proportions of different ethnic groups in one’s community, de Souza Briggs (2007) analyzed the friendship patterns of over 20,000 adults in the United States. These data suggested that the single greatest predictor of whether or not a European American adult reported having a cross-race friendship was the region of the country in which the individual resided. Even so, the actual rates of cross-race friendships fall short of the predicted probability (as estimated by a random choice model given the racial distribution of one’s local area) for all ethnic groups (de Souza Briggs, 2007). In other words, even though living in a more diverse area provided increased opportunity to form cross-race friendships, individual differences still account for whether or not people actually formed cross-race friendships.

The current study will examine the prospective effects of intergroup and intragroup contact and friendships on changes in racial identity status in a 3-year longitudinal sample of African American adolescents living in a predominately White mid-western town. Interracial and intraracial contact is operational zed in two ways: 1). as students’ reports of the proportion of other Black youth in their classes and clubs, and 2). as friendships, the number of close White and close Black friends each student reports. We hypothesize that interracial contact and intraracial contact may or may not have independent effects on whether youths’ racial identities change or remain stable. Instead, we do expect that contact and context will interact to determine whether there are changes in racial identity over time. For the purposes of this paper, context is operational zed as diversity using school-level information about the racial composition of each student’s school.

Method

Participants

These data are drawn from a 3-year longitudinal study of racial identity development, racial socialization, and psychological adjustment among African American adolescents residing in the Midwest. About 15% of residents in the school district reported being African American, while 54% reported being of European American descent. There were more females than males in the study (60%) and the median family income was reported by parents to be between $40,000–49,000. Although the median income for African American families in this community is greater than the national average range ($30,000 – $39,000), there is variation for the participants’ families.

Students began the study either in the 7th, 8th, 9th, or 10th grade (mean age = 13.83 years old, SD = 1.11), and were administered surveys once a year for 3 years. Students attended 10 schools in the same school district (six middle and four high schools). At all three time points, data were collected from both an adolescent and his/her primary caregiver. Five hundred and forty six students completed surveys during the first year of the study. In year 2, 379 of those students returned. A total of 260 adolescents completed all three time points. With the exception of 1 school, all schools were predominately White, therefore, for ease and consistency of interpretation, the predominately Black school was omitted from the analyses presented here. As such, the current study includes the 224 adolescents who had complete data at all 3 time points. To address whether the data were missing at random, chi-square and ANOVA analyses compared adolescents with complete data across the 3 time points to adolescents who were omitted from the current study for not having data at all 3 times points. Examining gender and racial identity variables, there were no significant differences between adolescents who completed all 3 waves of the study compared to those who only completed 1 or 2 waves (gender (χ2 (2) = 1.08, n.s.); exploration: F (2,543) = .28, n.s.; commitment: F (2, 543) = 2.49, n.s.)).

Procedure

The specific procedures for the longitudinal study have been described elsewhere (Seaton, et al., 2009). All adolescents identified as African American by the school district were contacted by phone or mail to participate in the study. At each survey administration, adolescents were asked to sign assent forms. Adolescents completed pencil and paper surveys in small groups after school and sessions lasted between 45 and 75 minutes. Students were compensated with $30, $40, and $50 gift certificates to the local mall, for each year of the study respectively.

Measures

Racial Identity

The Multigroup Ethnic Identity Measure (MEIM) is comprised of four subscales: affirmation and belonging, identity achievement, racial behaviors and other-group orientation (Phinney, 1992). The identity achievement subscale, which measured exploration and commitment, was used in the present study. The scale consists of items with responses ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 4 (strongly agree), such that higher scores represent strong endorsement of their respective constructs. Previous research using the MEIM reported a two-factor solution consisting of affirmation/belonging (affirmation, belonging and commitment items) and identity search (exploration and ethnic behavior items) (Phinney, 1992; Roberts, et al., 1999). However, previous work has not exclusively focused on the achievement subscale, which measures exploration and commitment (Phinney, 1992). Since the goal of the present study was to create the identity statuses from exploration and commitment levels, it was appropriate to separate the achievement subscale into exploration and commitment dimensions.

A confirmatory factor analysis was conducted to discern whether the achievement subscale consisted of two oblique latent factors with exploration and commitment items at all three time periods. The results indicate an average fit to the data for Time 1 (X2 = 25.19, df = 8, X2/df = 3.15, TLI = .82, CFI = .93 and RMSEA = .10), Time 2 (X2 = 18.49, df = 8, X2/df = 2.31, TLI = .91, CFI = .96 and RMSEA = .08) and Time 3 (X2 = 47.99, df = 8, X2/df = 5.99, TLI = .62, CFI = .86 and RMSEA = .15) providing an empirical justification for separating the achievement subscale of the MEIM into exploration and commitment indices.

Since analyses were conducted over a 3-year time frame to measure change in racial identity, it was important to establish that observed change be due to differences in youths’ reports and not measurement variance. In order to examine invariance, differences in the Chi Square statistic were examined over time for the unconstrained model, the constrained measurement weights model and the constrained measurement intercepts model. Differences in the Chi Square statistic involve comparing the change in X2 to a critical ratio. The test comparing the unconstrained model with the constrained measurement weights model was not significant, ΔX2 = 7.05, with the critical ratio equivalent to 15.51. The test comparing the unconstrained model with the constrained measurement intercepts model was not significant, ΔX2 = 28.75, with the critical ratio equivalent to 31.41. Thus, the results suggest that the confirmatory factor analytic models are invariant across time.

The resulting exploration subscale consists of four items rated on a four-point Likert scale, which range from strongly disagree to strongly agree (Time 1 M = 2.87, SD = .63; Time 2 M = 2.82, SD = .57, Time 3 M = 2.79, SD = .64), and a sample item includes “I think a lot about what being Black means for my life” (Time 1 α =.66; Time 2 α =.63; Time 3 α =.64). The commitment subscale has two items rated on a four-point scale (Time 1 M = 3.09, SD = .70; Time 2 M = 3.02, SD = .72, Time 3 M = 2.98, SD = .72) and a sample item includes “I understand pretty well what being Black means to me” (Time 1 α =.68; Time 2 α =.69; Time 3 α =.71).

Because the Cronbach’s alphas for the exploration and commitment variables included significantly fewer items than the full-item MEIM, the Spearman-Brown Formula was used to calculate the estimated Cronbach’s alphas if the subscales included 12 items (equivalent to the full-item MEIM). The estimated Cronbach’s alphas are: exploration (Time 1 α =.83; Time 2 α=.83; Time 3 α=.85) and commitment (Time 1 α=.83; Time 2 α=.84; Time 3 α=.82). These coefficients are comparable to existing research employing the 12-item MEIM; for example, α=.82 (Roberts, et al., 1999), α=.75 (McMahon & Watts, 2002), and α=.82 (Bracey, Bamaca, & Umana-Taylor, 2004). Scores for each subscale were developed by averaging across the items, and higher scores are indicative of high levels of exploration or commitment.

Interracial contact

Two questions were asked: “Which of the following best describes the racial makeup of the students in most of your classes?” and “Which of the following best describes the racial makeup of the people in most of the clubs, teams, or other organizations you are currently involved in?” Responses included 1 (almost all White students), 2 (more White than Black students), 3 (same number of Black and White students), 4 (more Black than White students) to 5 (almost all Black students). These two items were averaged together to estimate contact (M = 2.37, SD = .92). Higher scores indicate more contact with same-race, Black youths.

Friendships

As another measure of contact (interracial and intraracial) we assessed youths’ reported friendships. “How many of your close friends are Black?” assessed intraracial close friendships. An analogous question, “How many of your close friends are White?” assessed interracial close friendships. Responses included 1 (None), 2 (A few), 3 (Half), 4 (Most) to 5 (All). To keep interracial and interracial friendships distinct, these items were kept separate and higher scores represent more close friendships with Black and White students (M = 3.07, SD = .78; M = 2.60, SD = .75, respectively).

School diversity index

The racial diversity of each school was obtained with archival data from the school district. The racial diversity of each student’s school was computed based on information about the percentage of African American, Asian, White, Hispanic, Middle Eastern, Native American, multiethnic and other students. Employing methods described in Juvonen and colleagues (2006), the racial diversity of each student’s school was computed based on information about the percentage of students in each racial group. Using information about the number of different racial/ethnic groups (g) and the proportion of individuals (p) who are members of each group (i), the index (DC) provides an estimate of the relative probability that two randomly selected students are from different racial/ethnic groups:

Higher scores (range from 0 to 1) indicate more diversity (i.e., presence of other racial minorities), whereas lower scores indicate less diversity (i.e., predominately White) and indicators were computed for all three time points (Time 1 M = .57, SD = .09; Time 2 M = .57, SD = .08; Time 3 M = .58, SD = .08).

Results

Correlations between the primary study variables are presented in Table 1. Among the Time 1 variables, reporting having more contact with Black students in classes and clubs was positively associated with reporting having more close Black friends, fewer close White friends, and higher school diversity. Reporting more close Black friends was associated with having fewer close White friends. Similar patterns were observed among the Time 2 variables. Among the Time 3 variables, one difference is noted: the composition of classes and clubs is no longer associated with the school diversity index. Examining the correlations across adjacent time points, Time 1 composition of classes and clubs is positively correlated with reports at Time 2. Time 1 composition of classes and clubs is also positively associated with having more close Black friends but negatively associated with having more close White friends. Reporting more close Black friends at Time 1 was positively associated with having more contact with Black students, more close Black friends, and fewer White close friends at Time 2. The number of close White friends reported at Time 1 was negatively associated with close Black friends at Time 2, but positively associated with close White friends at Time 2. School diversity at Time 1 was associated with more contact with Blacks; more close Black friends, and school diversity at Time 2. However, school diversity at Time 1 was negatively associated with close White friends at Time 2.

Table 1.

Correlation Between the Time 1, Time 2 and Time 3 Study Variables

| Time 1 | Time 2 | Time 3 | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | ||

| Time 1 | 1. Composition of classrooms and clubs |

-- | .27** | −.16** | .18* | .38** | .25** | −.27** | .02 | .36** | .28** | −.26** | .05 |

| 2. Close Black Friends |

-- | −.67** | .11 | .25** | .64** | −.54** | .00 | .27** | .64** | −.53** | −.03 | ||

| 3. Close White friends |

-- | −.07 | −.11 | −.59** | .66** | .03 | −.19** | −.56** | .55** | .04 | |||

| 4. School Diversity | -- | .22** | .18** | −.19* | .82** | .07 | .17 | −.22** | .75** | ||||

| Time 2 | 1. Composition of classrooms and clubs |

-- | .25** | −.19** | .19** | .37** | .31** | −.19** | .11 | ||||

| 2. Close Black Friends |

-- | −.64** | .05 | .28** | .62** | −.49** | .07 | ||||||

| 3. Close White friends |

-- | −.08 | −.26** | −.55** | .64** | −.02 | |||||||

| 4. School Diversity | -- | −.03 | .07 | −.11 | .84** | ||||||||

| Time 3 | 1. Composition of classrooms and clubs |

-- | .31** | −.32** | −.06 | ||||||||

| 2. Close Black Friends |

-- | −67** | .07 | ||||||||||

| 3. Close White friends |

-- | −.09 | |||||||||||

| 4. School Diversity | -- | ||||||||||||

p < .05,

p < .01

Examination of the Time 2 and Time 3 adjacent time points suggest that there was stability in composition of classes and clubs. There was also a positive association between composition and close Black friends, but a negative association with close White friends. Consistent with previous time points, there was a negative association between reports of close White friends and close Black friends between Time 2 and Time 3, but stability in reports of the same racial groups over time. Finally, stability was observed for reports of school diversity at Time 2 and Time 3. Looking over a 2-year period, having more Black students in classes and clubs at Time 1 was positively associated with the same variable at Time 3. And as with previous time points, Time 1 contact was positively associated with having more close Black friends and negatively associated with having close White friends. Having many close Black friends at Time 1 was associated with having many close Black friends at Time 3, fewer close White friends, and reporting more Blacks in classes and clubs. Again, stability was observed for having close White friends from Time 1 to Time 3, but it was also associated with having fewer close Black friends and reporting fewer Black students in classes and clubs. The school diversity index at Time 1 was positively associated with having more close Black friends at Time 3, as well as school diversity at Time 3. School diversity at Time 1 was negatively associated with reports of close White friends at Time 3. Since the school diversity index over the three time points was so highly correlated, a mean was computed of the 3 indices and this index was used for the analyses that follow.

Racial Identity Statuses

Before examining change in racial identity statuses, we first determined which racial identity clusters were present in the data. Consistent with racial identity status theory and with previous research (Yip, et al., 2006), we expected to find four identity statuses that reflect the diffused, foreclosed, moratorium, and achieved profiles. K Means cluster analyses were utilized to identify homogenous racial identity statuses among standardized exploration and commitment variables. K Means analyses are the most appropriate technique when there is a theoretical rationale for a specific number of clusters (Hair & Black, 2000). The specific statistical techniques used to create the four identity status groups have been described elsewhere (Yip, et al., 2006). Consistent with Phinney’s (1989) identity formation model, the data suggested the presence of four distinct identity profiles. The first profile had significantly lower scores on the exploration and commitment subscales and was classified as diffuse (Time 1 n=21; Time 2 n=31; Time 3 n=36). A second cluster reported lower scores on the exploration subscale and higher scores on the commitment subscale was classified as foreclosed (Time 1 n=48; Time 2 n=55; Time 3 n=28). A third cluster fit the description for moratorium, with higher scores on the exploration subscale and lower scores on the commitment subscale (Time 1 n=65; Time 2 n=74; Time 3 n=80). The final cluster was classified as achieved, with higher scores on both the exploration and commitment subscales (Time 1 n=77; Time 2, n=51; Time 3 n=67).

Interracial/Intraracial Contact and School Diversity

The racial identity status variable assessed whether individuals changed over time. Individuals who remained in the same status over time were labeled as Constant, whereas individuals who changed identity status groups over time were labeled as Change. Employing these coding methods, we observed that between Time 1 and Time 2, 42% of the sample reported no change in their racial identity status whereas the remaining 58% reported a change in their identity status. Between Time 2 and Time 3, 36% of the sample reported remaining in the same identity status while 64% did not. Finally, over the 2-year period between Time 1 and Time 3, 38% of students reporting staying in the same identity status while 62% reported moving from one status to another.

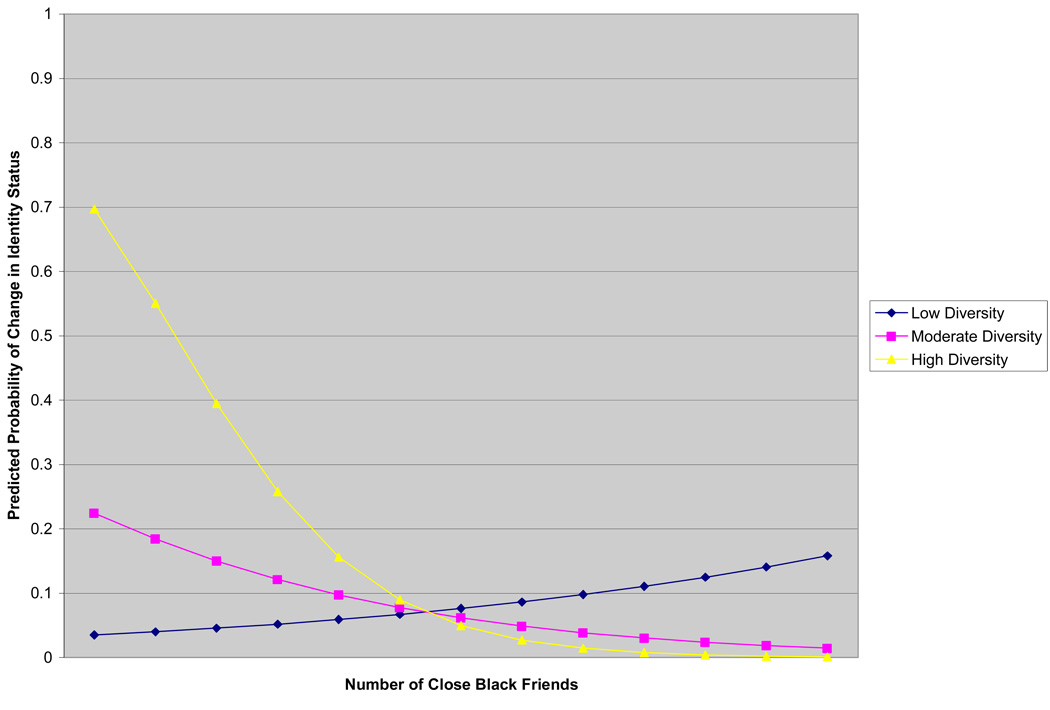

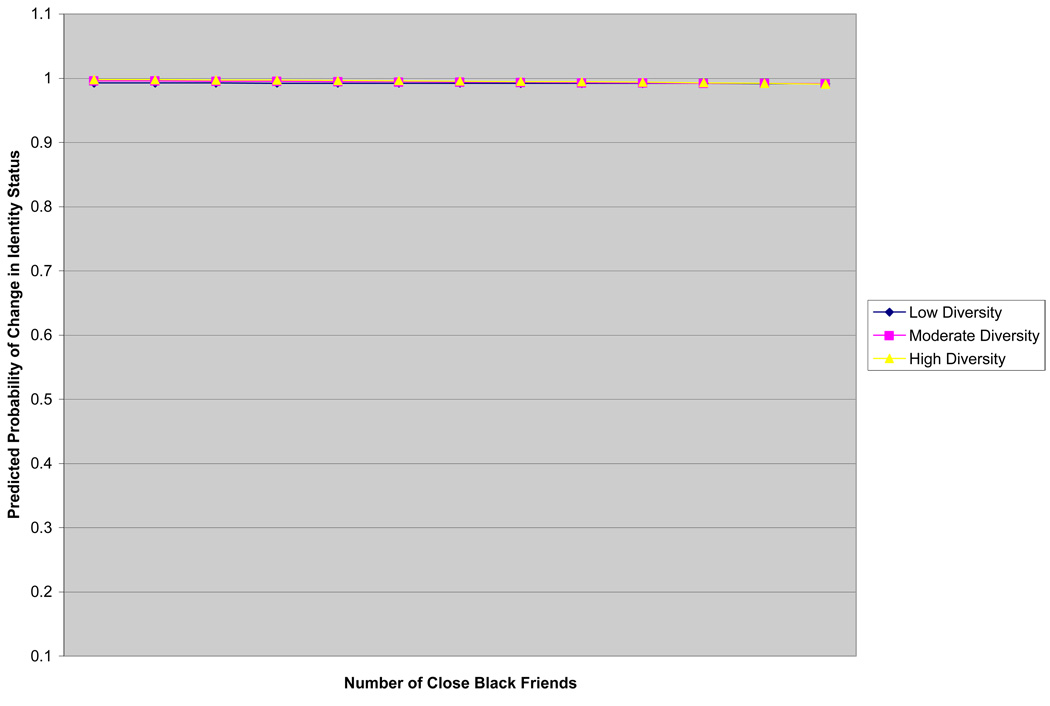

The next step was to examine how interracial and intraracial contact prospectively predicted the observed changes in identity status. As such, binomial logistic regression analyses were conducted where identity change from Time 1 to Time 2 was coded as 1, and identity stability from Time 1 to Time 2 was coded as 0. Student age and gender were included as covariates. School diversity (mean of Time 1, 2, 3), number of close White friends (Time 1), number of close Black friends (Time 1), contact with Black students in classrooms and clubs (Time 1), the three possible interactions of school diversity with each of the three other independent variables, and the two possible interactions between school diversity, contact and number of close Black and White friends were included as predictors (Table 2). A main effect of contact with Blacks in classrooms and clubs was observed such that more contact was associated with an increased likelihood of change in racial identity status. In addition, a 3-way interaction between contact, diversity and number of close Black friends was found which is illustrated jointly in Figures 1 and 2. To graph the 3-way interaction, a median split was computed for contact with Black students (Figure 1: Low Contact with Blacks; Figure 2: High Contact with Blacks). Among students who reported having low contact with Black students (Figure 1), those with few close Black friends who reported attending schools with higher diversity (i.e., presence of other minorities) reported being more likely to change their identity status from Time 1 to Time 2. On the other hand, among students who reported having high contact with Black students (Figure 2) school diversity and number of close Black friends had no association with the probability of identity change over time.

Table 2.

Logistic Regression Predicting Probability of Identity Status Change From Time 1 to Time 2

| B | SE | |

|---|---|---|

| Constant | .66 | 1.93 |

| Age | .03 | .13 |

| Gender | −.50 | .31 |

| School Diversity (mean Time 1, 2, 3) | 1.54 | 1.57 |

| Close White Friend - Time 1 | .11 | .25 |

| Close Black Friend - Time 1 | −.04 | .22 |

| Contact - Time 1 | .50** | .19 |

| School Diversity × Close White Friend - Time 1 | 1.00 | 2.65 |

| School Diversity × Close Black Friend - Time 1 | −.46 | 2.39 |

| School Diversity × Contact - Time 1 | 1.08 | 1.87 |

| School Diversity × Contact × White Friend – Time 1 | −5.62 | 3.29 |

| School Diversity × Contact × Black Friend – Time 1 | −6.49* | 3.05 |

p < .05,

p < .01

Figure 1.

Change from T1 to T2 with T1 Predictors: 3-way interaction between Close Black Friends, Contact, and Diversity – Low Contact with Blacks in Classes and Clubs

Figure 2.

Change from T1 to T2 with T1 Predictors: 3-way interaction between Close Black Friends, Contact, and Diversity – High Contact with Blacks in Classes and Clubs

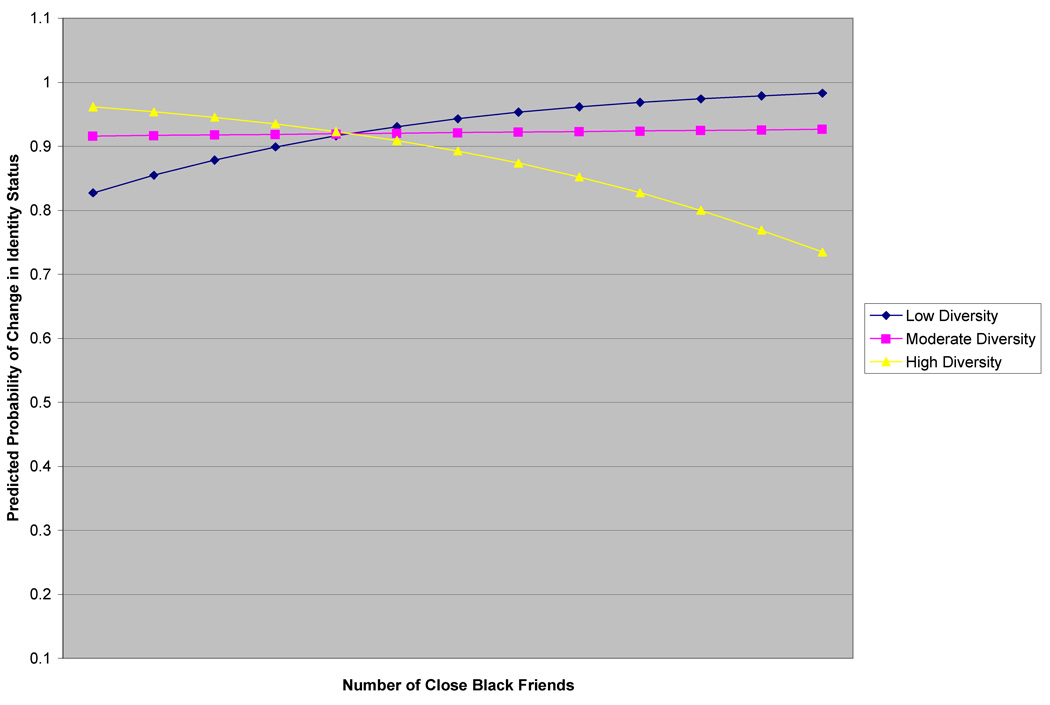

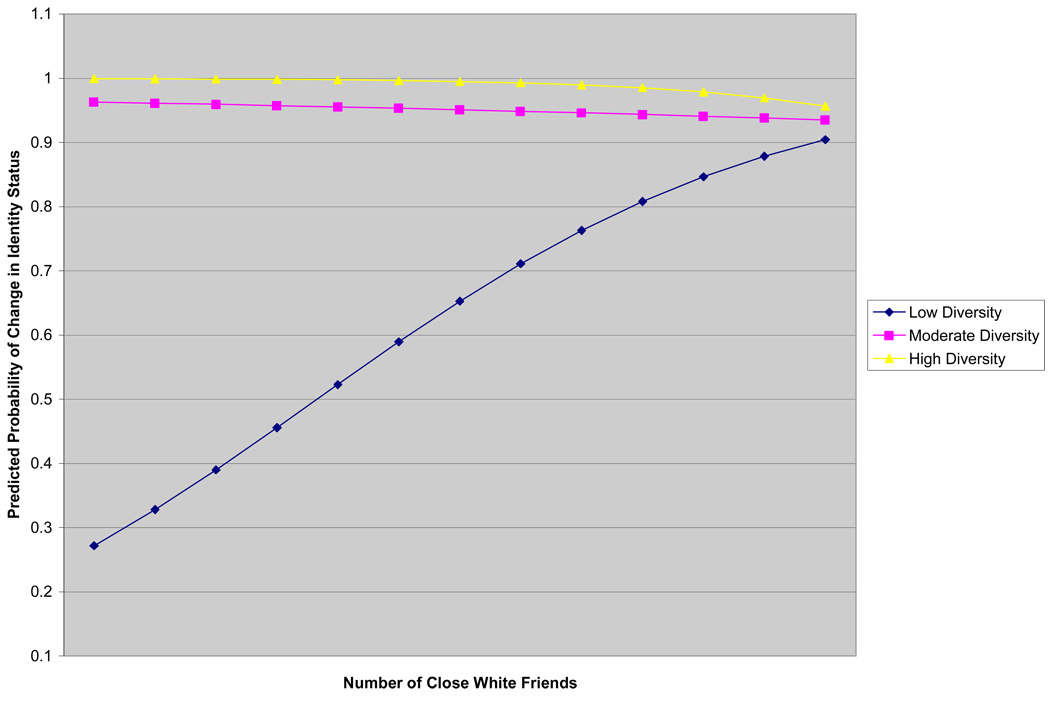

Examining the same relationships to predict change in racial identity from Time 2 to Time 3, there was evidence of a two-way interaction between school diversity and number of close Black friends (Table 3). As illustrated in Figure 3, as students reported an increase in number of close Black friends, students in low diversity schools (i.e., predominately White) reported being more likely to report a change in identity status from Time 2 to Time 3. For students attending high diversity schools (i.e., presence of other minorities), however, it seems that reporting more close Black friends was associated with a decreased likelihood of change in identity status.

Table 3.

Logistic Regression Predicting Probability of Identity Status Change From Time 2 to Time 3

| B | SE | |

|---|---|---|

| Constant | 2.46 | 2.00 |

| Age | −.07 | .14 |

| Gender | −.50 | .32 |

| School Diversity (mean Time 1, 2, 3) | .60 | 1.72 |

| Close White Friend - Time 2 | .01 | .24 |

| Close Black Friend - Time 2 | −.21 | .22 |

| Contact - Time 2 | .18 | .17 |

| School Diversity × Close White Friend - Time 2 | −4.35 | 2.98 |

| School Diversity × Close Black Friend - Time 2 | −6.17* | 2.92 |

| School Diversity × Contact - Time 2 | .28 | 1.85 |

| School Diversity × Contact × White Friend – Time 2 | 2.42 | 3.01 |

| School Diversity × Contact × Black Friend – Time 2 | .14 | 1.99 |

p < .05

Figure 3.

Change from T2 to T3 with T2 Predictors: 2-way interaction between Diversity and Close Black Friends

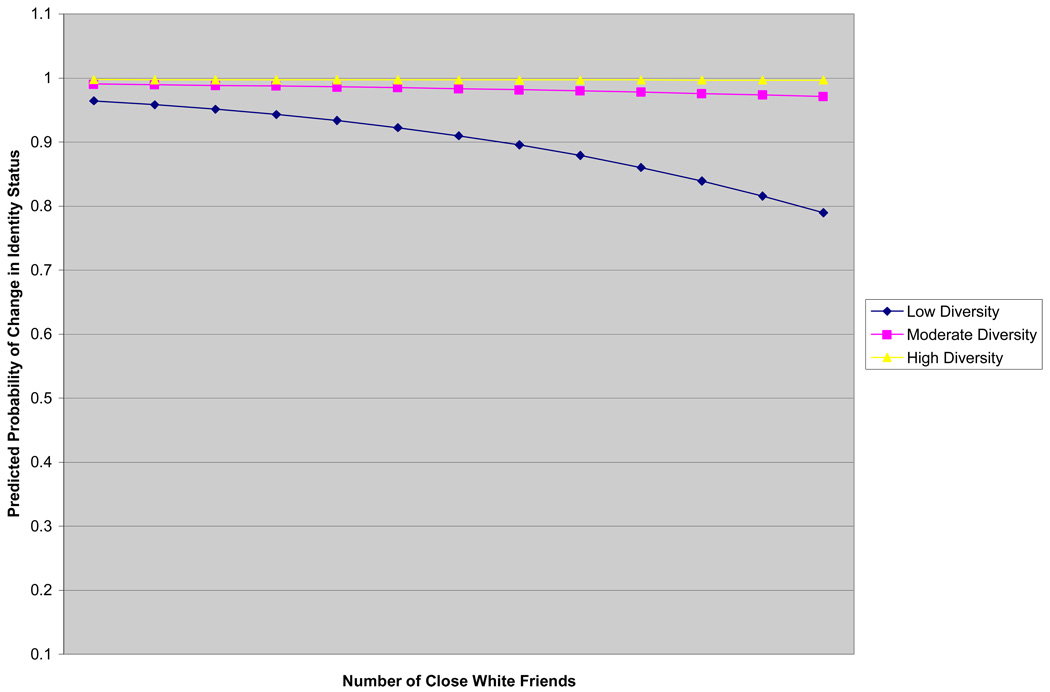

Analyses were also conducted examining change during the two-year period between Time 1 and Time 3, and unlike the previous set of analyses, an effect was observed for number of close White friends (Table 4). Namely, there was a main effect of number of close White friends where having more White friends was associated with an increased probability of identity change. As well, there was a main effect of having close Black friends associated with an increase likelihood of identity change. Finally, there was also evidence for a 3-way interaction between contact with Black students, school diversity and number of close White friends. To depict this interaction, the sample was divided using a median split of contact with Black students (Figures 4 & 5). As illustrated in Figure 4, student who reported low contact with Black students were less likely to report a change in their identity status if they attended low diversity schools (i.e., predominately White) and reported having many close White friends. Alternatively, among students reporting high contact with Black students (Figure 5), attending a predominately White school was associated with a decreased probability of identity change for adolescents reporting having few close White friends.

Table 4.

Logistic Regression Predicting Probability of Identity Status Change From Time 1 to Time 3

| B | SE | |

|---|---|---|

| Constant | 3.27 | 2.06 |

| Age | −.16 | .14 |

| Gender | −.32 | .32 |

| School Diversity (mean Time 1, 2, 3) | −.03 | 1.71 |

| Close White Friend - Time 1 | 1.01** | .31 |

| Close Black Friend - Time 1 | .81** | .28 |

| Contact - Time 1 | .10 | .18 |

| School Diversity × Close White Friend - Time 1 | 3.81 | 3.14 |

| School Diversity × Close Black Friend - Time 1 | 1.81 | 2.73 |

| School Diversity × Contact - Time 1 | −3.31 | 2.10 |

| School Diversity × Contact × White Friend – Time 1 | −8.24* | 3.92 |

| School Diversity × Contact × Black Friend – Time 1 | −5.42 | 3.42 |

p < .05,

p < .01

Figure 4.

Change from T1 to T3 with T1 Predictors: 3-way interaction between Close White Friends, Contact, and Diversity – Low Contact with Blacks in Classes and Clubs

Figure 5.

Change from T1 to T3 with T1 Predictors: 3-way interaction between Close White Friends, Contact, and Diversity – High Contact with Blacks in Classes and Clubs

Discussion

The current study explored how contact with Black students in classes and clubs, close friendships with Black and White students, and school-level diversity independently and jointly predict whether African American adolescents will report change or stability in their racial identity status over 1- and 2-year periods. The data suggested that there were independent effects of contact with Black peers, close White friends, and close Black friends. Interestingly, however, school-level diversity did not appear to have a main effect on the probability of change or stability in racial identity status. Instead, school diversity was observed to have a joint influence with close friendships and contact in classes and clubs. These results point to the active role that youths’ play in their own identity development. That is, the school setting does not shape racial identity development from a top-down approach; rather the adolescent creates his/her developmental context through choices like one’s close friendship network. To parallel the analyses, the results are discussed in the same order in which they were analyzed: first examining change between adjacent time points (i.e., T1 to T2, T2 to T3), then examining change over a 2-year period (i.e., T1 to T3).

Turning first to the change between T1 and T2, the results indicate a main effect of increased contact with Blacks in classrooms and clubs as linked to an increased likelihood of changing racial identity status among African American youth. This finding is consistent with other research indicating that racial identity was strengthened in the presence of same-race peers. For example, more in-group peer interactions were associated with a stronger sense of ethnic identification among diverse youth (Phinney, Horenczyk, Liebkind, & Vedder, 2001) and same-race peer relationships were associated with resolutions in racial identity formation among African American college students (Tatum, 2004). The present findings and past research suggest that increased contact with same-race peers is linked to changes in racial identity status over time. Though in the current study it is unknown if the nature of this change is progression or regression (as outlined in the identity status model (Marcia, 1966; Phinney, 1992)), change is occurring under the influence of Black peers suggesting that same-race peers have an important influence on racial identity development.

In addition to this main effect, contact with Blacks in classes and clubs also appeared to interact with school diversity and number of close Black friends to predict change or stability in racial identity between the first and second year of the study. Specifically, African American youth with few close Black friends in high diversity settings were more likely to change their racial identity status from Time 1 to Time 2. Recall that low diversity settings are characterized as predominately White schools while high diversity settings offer the presence of both same and different race peers. We suggest that this finding indicates a mismatch between the adolescent’s choice of friends and what the context allows with respect to opportunities for forming friendships. As suggested by the correlations between close Black and White friends, it seems that youth with few Black friends may have more White friends, but the increased numbers of Blacks in classes and clubs affords new opportunities for racial encounters. Nigresence theory posits that racial encounters result in individuals reevaluating the role that race plays in their lives, which results in an advanced and nuanced racial identity for African Americans (Cross & Fhagen-Smith, 2001). Nigresence theory suggests that racial encounters may be negative (e.g., racially discriminatory experiences) or positive (e.g., making the soccer team); therefore, youth with few Black friends may be experiencing positive encounters as they come into increased contact with their African American peers. These encounters may be more probable in high diversity settings given the increased numbers of other African American youth, and they may result in increased exploration or commitment which would be coded as a change in racial identity status in the current study.

Turning to the analyses examining predictors of the change from T2 to T3, the data indicate interactive effects between school diversity and having more close Black friends. Specifically, in high diversity settings, youths who reported having many close Black friends also reported that their racial identity statuses were less likely to change. The findings suggest that intraracial friendships have differential influences on racial identity development depending on the level of diversity in the setting. One explanation for this finding is that low diversity settings increase the likelihood of negative interactions (i.e., discriminatory treatment due to minority status) which may be linked to racial identity changes. Previous research indicates that greater school diversity was related to less positive perceptions of the general school climate (Benner, Graham, & Mistry, 2008) given that discrimination is believed to be maximized in evenly mixed racial contexts (Sigelman, Bledsoe, Welch, & Combs, 1996). Additional research indicates that perceptions of racially discriminatory acts by peers were associated with increased identity exploration levels over time among African American youth (Pahl & Way, 2006). Thus, low diversity levels may be associated with more perceptions of discrimination among African American youth, and these perceptions of racial discrimination may be influencing the increased likelihood of changing racial identity status groups. A second explanation is the quality of contact that African American youth have with Black and White friends. Diverse settings afford Black youth more opportunities to have White friends but previous research suggests that ethnic minorities had less positive interactions with White friends than with friends of their same racial background (Shelton & Richeson, 2006). Yet, African American children who had more contact with Black friends considered the contact to be positive in that it helped prepare them for discriminatory treatment (Rowley, et al., 2008). Thus, the nature of the interactions is distinct depending on the race of the friends and research suggests that less positive contact increases with more White friends. As such, these interactions may influence the degree to which African American youth change their racial identity status groups.

Lastly, examining change over a 2-year period from T1 to T3, the data suggested an interaction between context, contact with Black students and close friendships with White students. It appears that being in a predominantly White setting is an important factor for racial identity change when African American youth report having a lot of White friends but little contact with Blacks in their classes and clubs. Similarly, a predominantly White setting matters when youth have few close White friends and a lot of contact with Blacks in their classes and clubs. In both groups, youths are in predominately White settings, but one group associates with a lot of White friends while the other group does not, and there is a decreased likelihood of racial identity change in both scenarios. One explanation is related to a tenet of the Contact Hypothesis, which posits that more intergroup contact results in more attention toward out-group members (Pettigrew, 1998). The nature of the predominately White setting may result in increased awareness and attention to interactions with White out-group as opposed to Black in-group members. Hence, this focus may decrease the probability of change in the racial identity status groups among African American youth since exploration and commitment related to being African American are minimized. The present findings are contrary to previous research conducted with White (Hamm, 2000) and Latino youths (Umana-Taylor, 2004) showing that cross-race friendships were influential for ethnic identity. In the present sample, students reported that about “half” of their friends were of each group on both the close Black friend and close White friend variable. Therefore, it seems as though most of the students in this sample did have both in-group and out-group friendships regardless of the diversity of the school. Despite this similarity, it seems that only close friendships with same-race peers interacted with school diversity to influence changes in youths’ racial identity over time. This may be true because this study was conducted in a predominately White town, so the significance and meaning of close Black friends was more influential for changes in racial identity; a finding consistent with prior research (Phinney, Romero, et al., 2001; Tatum, 2004).

Although the current study offers a more nuanced and detailed examination of the relationships between contact, context and identity change, there are a few limitations that require consideration. Although cluster analysis provides a valuable method for classifying individuals, the technique is sample dependent. An additional limitation concerns the lack of assessment for previous development in that cluster analysis does not account for previous exploration or commitment levels. Another consideration is that the current study only examined how school-based peer interactions and diversity influence racial identity outcomes and research suggests that only 28% of youths who report out-group friends in school also report having out-group friends outside of school (DuBois & Hirsch, 1990). Therefore, it would seem important for future research to consider interracial and interracial interactions that occur outside of the school context. In addition, the time period for change is unclear given that the data were collected once a year. Despite the fact that the observed changes in identity status at one- and two-year intervals are consistent with developmental theories suggesting adolescence is an important time for identity exploration and construction (Erikson, 1968), data collected at smaller intervals might suggest more stability and/or change. Similarly, data collected during smaller time intervals might provide more information about how antecedents (i.e., school diversity) are related to subsequent changes in identity status. It should also be noted that the sample size was too small to allow for more detailed analyses to identify subgroups of identity change trajectories (e.g., regressing from achieved to foreclosed vs. regressing from achieved to moratorium). For example, it is plausible that the interaction of school diversity and Black friends may be associated with specific trajectories. It is also important for future research to consider the content and quality of interracial and intraracial interactions and how these dimensions contribute to youths’ thoughts and feelings about their racial group membership. Finally, the current study only examines the racial dimension of adolescents’ identity development and does not capture the possibility that while adolescents may not be changing in their levels of commitment and exploration of their racial identity, they could be changing in terms of developing a bicultural or multicultural perspective.

Nevertheless, the current study represents an important and unique contribution to the racial identity development literature by assessing intergroup and intragroup contact and school diversity as antecedents of change. While the Contact Hypothesis posits that contact will have a positive impact on reducing prejudice and bias toward out-group members (Pettigrew & Tropp, 2006), the results suggest that intergroup contact has important implications for racial identity development among African American youth. Specifically, school diversity and having Black friends influence whether African American youth change racial identity status groups or remain stable across time. As racial identity has been shown to be an important construct for African American and minority youth, the present study advances our understanding of key antecedents for this integral developmental process.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grants from the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH 5 R01 MH061967-03) and the National Science Foundation (BCS-9986101) awarded to the third author.

Contributor Information

Tiffany Yip, Fordham University.

Eleanor K. Seaton, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill

Robert M. Sellers, University of Michigan

References

- Alba R, Nee V. Rethinking the American mainstream: Assimilation and contemporary immigration. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Benner AD, Graham S, Mistry RS. Discerning direct and mediated effects of ecological structures and processes on adolescents' educational outcomes. Developmental Psychology. 2008;44(3):840–854. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.44.3.840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bracey JR, Bamaca MY, Umana-Taylor AJ. Examining ethnic identity and self-esteem among biracial and monoracial adolescents. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2004;33(2):123–132. [Google Scholar]

- Cross WE, Jr, Fhagen-Smith P. Patterns of African American identity development: A life span perspective. In: Jackson B, Wijeyesinghe C, editors. New perspectives on racial identity development: A theoretical and practical anthology. New York, NY: New York University Press; 2001. pp. 243–270. [Google Scholar]

- de Souza Briggs X. 'Some of my best friends are….': Interracial friendships, class, and segregation in America. City & Community. 2007;6(4):263–290. [Google Scholar]

- DuBois DL, Hirsch BJ. School and neighborhood friendship patterns of Blacks and Whites in early adolescence. Child Development. 1990;61(2):524–536. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1990.tb02797.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutton SE, Singer JA, Devlin AS. Racial identity of children in integrated, predominantly White, and Black schools. Journal of Social Psychology. 1998;138(1):41–53. doi: 10.1080/00224549809600352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erikson E. Identity: Youth and Crisis. New York: Norton; 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Hair JFJ, Black WC. Cluster Analysis. In: Grimm LG, Yarnold PR, editors. Reading and Understanding More Multivariate Statistics. Washington, D.C: American Psychological Association; 2000. pp. 147–205. [Google Scholar]

- Hamm JV. Do birds of a feather flock together? The variable bases for African American, Asian American, and European American adolescents' selection of similar friends. Developmental Psychology. 2000;36(2):209–219. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juvonen J, Nishina A, Graham S. Ethnic Diversity and Perceptions of Safety in Urban Middle Schools. Psychological Science. 2006;17(5):393–400. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2006.01718.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kao G, Joyner K. Do Hispanic and Asian Adolescents Practice Panethnicity in Friendship Choices? Social Science Quarterly. 2006;87(1):972–992. [Google Scholar]

- Kao G, Vaquera E. The Salience of racial and ethnic identification in friendship choices among Hispanic adolescents. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 2006;28(1):23–47. [Google Scholar]

- Kubitschek WN, Hallinan MT. Tracking and students' friendships. Social Psychology Quarterly. 1998;61(1):1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Lee RM, Noh C-Y, Yoo HC, Doh H-S. The psychology of diaspora experiences: Intergroup contact, perceived discrimination, and the ethnic identity of Koreans in China. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2007;13(2):115–124. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.13.2.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcia JE. Development and validation of ego-identity status. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1966;3:551–558. doi: 10.1037/h0023281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcia JE. Identity in adolescence. In: Adelson J, editor. Handbook of adolescent psychology. New York, NY: Wiley; 1980. pp. 159–187. [Google Scholar]

- Masson CN, Verkuyten M. Prejudice, ethnic identity, contact and ethnic group preferences among Dutch young adolescents. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 1993;23(2):156–168. [Google Scholar]

- McMahon SD, Watts RJ. Ethnic identity in urban African American youth: Exploring links with self-worth, aggression, and other psychosocial variables. Journal of Community Psychology. 2002;30:411–431. [Google Scholar]

- Mickelson RA, Heath D. The effects of segregation and tracking on African American high school seniors' academic achievement. Journal of Negro Education. 1999;68(4):566–586. [Google Scholar]

- Molina LE, Wittig MA. Relative Importance of Contact Conditions in Explaining Prejudice Reduction in a Classroom Context: Separate and Equal? Journal of Social Issues. 2006;62(3):489–509. [Google Scholar]

- Nier JA, Gaertner SL, Dovidio JF, Banker BS, Ward CM, Rust MC. Changing interracial evaluations and behavior: The effects of a common group identity. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations. 2001;4(4):299–316. [Google Scholar]

- Pahl K, Way N. Longitudinal trajectories of ethnic identity among urban Black and Latino adolescents. Child Development. 2006;77(5):1403–1415. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00943.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pettigrew TF. Intergroup contact theory. Annual Review of Psychology. 1998;49:65–85. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.49.1.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pettigrew TF. The Advantages of Multilevel Approaches. Journal of Social Issues. 2006;62(3):615–620. [Google Scholar]

- Pettigrew TF. Future directions for intergroup contact theory and research. International Journal of Intercultural Relations. 2007;32:187–199. [Google Scholar]

- Pettigrew TF, Tropp LR. A meta-analytic test of intergroup contact theory. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2006;90(5):751–783. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.90.5.751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phinney JS. Stages of ethnic identity in minority group adolescents. Journal of Early Adolescence. 1989;9:34–49. [Google Scholar]

- Phinney JS. The Multigroup Ethnic Identity Measure: A new scale for use with diverse groups. Journal of Adolescent Research. 1992;7(2):156–176. [Google Scholar]

- Phinney JS. A three-stage model of ethnic identity development in adolescence. In: Bernal ME, editor. (1993). Ethnic identity: Formation and transmission among Hispanics and other minorities. SUNY series, United States Hispanic studies. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press; 1993. pp. 61–79. [Google Scholar]

- Phinney JS, Horenczyk G, Liebkind K, Vedder P. Ethnic identity, immigration, and well-being: An interactional perspective. Journal of Social Issues. 2001;57(3):493–510. [Google Scholar]

- Phinney JS, Romero I, Nava M, Huang D. The role of language, parents, and peers in ethnic identity among adolescents in immigrant families. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2001;30(2):135–153. [Google Scholar]

- Portes A, Rumbaut RG. Legacies: The story of the immigrant second generation. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Quillian L, Campbell ME. Beyond black and white: The present and future of multiracial friendship segregation. American Sociological Review. 2003;68(4):540–566. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts RE, Phinney JS, Masse LC, Chen YR, Roberts CR, Romero A. The structure of ethnic identity of young adolescents from diverse ethnocultural groups. Journal of Early Adolescence. 1999;19(3):301–322. [Google Scholar]

- Rowley SJ, Burchinal MR, Roberts JE, Zeisel SA. Racial identity, social context, and race-related social cognition in African Americans during middle childhood. Developmental Psychology. 2008;44(6):1537–1546. doi: 10.1037/a0013349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarzwald J, Cohen S. Relationship between academic tracking and the degree of interethnic acceptance. Journal of Educational Psychology. 1982;74(4):588–597. [Google Scholar]

- Seaton EK, Scottham KM, Sellers RM. The Status model of racial identity development in African American adolescents: Evidence of structure, trajectories and well-being. Child Development. 2006;77(5):1416–1426. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00944.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seaton EK, Yip T, Sellers RM. A longitudinal examination of racial identity and racial discrimination among African American adolescents. Child Development. 2009;80(2):406–417. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01268.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shelton JN, Richeson JA. Ethnic minorities' racial attitudes and contact experiences with White people. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2006;12(1):149–164. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.12.1.149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sigelman L, Bledsoe T, Welch S, Combs MW. Making contact? Black-White social interaction in an urban setting. American Journal of Sociology. 1996;101(5):1306–1332. [Google Scholar]

- Tatum BD. "Why are all the Black kids sitting together in the cafeteria? " and other conversations about race. Basic Books; 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tatum BD. Family Life and School Experience: Factors in the Racial Identity Development of Black Youth in White Communities. Journal of Social Issues. 2004;60(1):117–135. [Google Scholar]

- Tropp LR. Perceived discrimination and interracial contact: Predicting interracial closeness among Black and White Americans. Social Psychology Quarterly. 2007;70(1):70–81. [Google Scholar]

- Umana-Taylor AJ. Ethnic identity and self-esteem: examining the role of social context. Journal of Adolescence. 2004;27(2):139–146. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2003.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yip T, Seaton EK, Sellers RM. African American racial identity across the lifespan: Identity status, identity context and depressive symptoms. Child Development. 2006;77(5):1503–1516. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00950.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]