SUMMARY

Social indicators suggest that African American adolescents are in the highest risk categories of those contracting HIV/AIDS (CDC, 2001). The dramatic impact of HIV/AIDS on urban African American youth have influenced community leaders and policy makers to place high priority on programming that can prevent youth’s exposure to the virus (Pequegnat & Szapocznik, 2000). Program developers are encouraged to design programs that reflect the developmental ecology of urban youth (Tolan, Gorman-Smith, & Henry, 2003). This often translates into three concrete programmatic features: (1) Contextual relevance; (2) Developmental-groundedness; and (3) Systemic Delivery. Because families are considered to be urban youth’s best hope to grow up and survive multiple-dangers in urban neighborhoods (Pequegnat & Szapocznik, 2000), centering prevention within families may ensure that youth receive ongoing support, education, and messages that can increase their capacity to negotiate peer situations involving sex.

This paper will present preliminary data from an HIV/AIDS prevention program that is contextually relevant, developmentally grounded and systematically-delivered. The collaborative HIV/AIDS Adolescent Mental Health Project (CHAMP) is aimed at decreasing HIV/AIDS risk exposure among a sample of African American youth living in a poverty-stricken, inner-city community in Chicago. This study describes results from this family-based HIV preventive intervention and involves 88 African American pre-adolescents and their primary caregivers. We present results for the intervention group at baseline and post intervention. We compare post test results to a community comparison group of youth. Suggestions for future research are provided.

Keywords: Prevent youth exposure to HIV, contextual relevance, developmental groundedness, systemic delivery, Chicago African American youth, developmental ecology of urban youth

INTRODUCTION

Social indicators suggest that African American adolescents are in the highest risk for contracting HIV/AIDS (CDC, 2001). Nationally, African Americans account for over 57% of all new HIV infections (CDC, 2004). Similarly, AIDS is the fourth leading cause of death among African American young adults–a group likely to have been infected during their adolescent years (CDC, 2001), Notably, a significant majority of reported HIV infection occurs among African American adolescents and young adults living in urban neighborhoods in US cities. For example, in the city of Chicago (where the study discussed in this paper was conducted) over 60% of newly reported HIV-infections occur among African Americans living in the poorest census tracks of the city. Further, inner-city African American youth accounted for more than 50% of all reported adolescent cases of HIV in Chicago (Illinois Department of Public Health, 2001).

The dramatic impact of HIV on urban African American youth has influenced community leaders and policy makers to place high priority on programming that can prevent youth’s exposure to the virus (Pequegnat & Szapocznik, 2000). Program developers are encouraged to design programs that reflect the developmental ecology of urban youth (Tolan, Gorman-Smith, & Henry, 2003). This often translates into three concrete programmatic features: (1) Contextual relevance embedding messages and strategies specifically tailored for youth living in an urban context, many of whom are growing up in poverty-stricken communities with high levels of social toxicity. The multiple and co-occurring risks for these youth underscore the need to address risks holistically (Bell, Flay, & Paikoff, 2002). (2) Developmental-groundedness–recognizing that urban youth face significant different risks and challenges as they move from younger to more mature phases of adolescence. Many preadolescents are not actually engaged in sexual behavior (Paikoff, 1996), but are indirectly exposed to the same risk factors that are stronger lures for older youth. Older youth are often in more potent risk situations and hence decision-making about sexual choices become more complex. Correspondingly, prevention programs must prepare youth to recognize risk situations, as well as to negotiate situations once they are unfolding (Hains & Herrman, 1989). (3) Systemic Delivery–working in proximal systems in which youth decision making unfold. For most youth, these systems include family and peer contexts. Families are often considered to be urban youth’s best hope to grow up and survive multiple dangers in urban neighborhoods (Pequegnat & Szapocznik, 2000). Hence, centering prevention within families may ensure that youth receive ongoing support, education, and value messages that can increase their capacity to negotiate peer situations involving sex.

Utilizing this framework, this article will present preliminary data from an HIV/AIDS prevention program that is contextually relevant, developmentally grounded and systemically-delivered. The Collaborative HIV/AIDS Adolescent Mental Health Project (CHAMP) is aimed at decreasing HIV/AIDS risk exposure among a sample of African American youth living in a poverty-stricken, inner-city community in Chicago. The CHAMP Program is distinctive because of a high intensity researcher-community collaboration that became the vehicle for designing the developmentally timed, family-based HIV/AIDS prevention program customized for urban youth. CHAMP taps into the construct of contextual relevance by teaming with community members to design an intervention that is laden with symbols, vocabulary, and topics indigenous to the neighborhood where the intervention is being implemented. All CHAMP curriculum is delivered by age group with material specifically targeted to the developmental tasks of pre adolescence and early-adolescence respectively. This ensures developmental appropriateness of each group. Finally, CHAMP is systematically delivered in neighborhood schools with facilitators from the community. Additionally, families are recruited by their fellow community members. This strategy eases the possibility of distrust of university based researchers and ensures the longevity of the intervention as the community has a sense of ownership. In prior publications, Madison and colleagues (2000) describe the collaborative partnership framework that under girds the CHAMP approach to prevention. In addition, Baptiste et al. (2004) describe how researcher and community members collaborated to design and deliver programs targeting youth at two developmental nodes, pre and early adolescence.

THE CHAMP PRE-ADOLESCENT PROGRAM

The CHAMP preadolescent program was designed for urban African American youth ages 9–11, and is based on the idea that prevention should begin early, to equip youth to resist pressure to engage in unprotected sexual activity, and by extension prevent HIV risk exposure. The program involves having youth participate with parents and/or other adult caregivers who can steer them through pubertal changes, increases in romantic thoughts and feelings, and social pressure to engage in risky behavior, which may involve sexual activity. In a prior paper, we noted that while less than 3% of urban pre-adolescents report, actually engaging in sex, many have thought about it and are in sexual possibility situations–where youth are alone with other youth in private settings without adult supervision. (Paikoff, 1996), Therefore, our preadolescent program focuses on: (a) increasing parent/caregivers’ and youth comfort in discussing puberty and the development of romantic or sexual feelings; (b) reducing time spent in sexual possibility situations; (c) increasing parental effectiveness around supervision and monitoring of youth in general, and of sexual possibility situations, in particular; (d) clarifying family values about sexual choices; and (e) increasing parent and youth’s knowledge about risks related to HIV/AIDS.

The preadolescent program is structured as a Multiple Family Group (MFG) intervention in which 6–8 families participate together. MFGs are designed to increase inter and intra family support and mutual aid, to decrease stigma parents and youth may experience about being involved in a group discussing sensitive family issues, and to create supportive, parent and youth peer-groups to problem solve about prevention strategies. The twelve MFG sessions in the preadolescent program are structured comparably. Families first meet together for about twenty minutes to focus on the topic of the meeting. This is followed by simultaneous parent and youth break out sessions which last for approximately 45 minutes. Youth sessions are aimed at creating a peer microcosm to practice negotiation and refusal skills in peer pressure situations. Youth role play scenarios that typically occur in urban settings. Further, they practice strategies for handling these situations also for talking with their parents about them (see Madison et al., 2000; McKay et al., 2000 for a more complete description).

Simultaneously, parents are also holding related discussions. Parents discuss monitoring strategies to reduce sexual possibility situations and problem solve about strategies to help youth deal with social pressure in an urban context. Parents are encouraged to support each other within groups, and outside of groups around the idea that mutual-aid and encouragement can enhance parenting overall. Further, parents also prepare to discuss sensitive topics with their youth by talking with other group members and the CHAMP facilitators. Following parent and youth break out groups, each family holds a discussion to allow parents and youth to exchange ideas on the day’s topic and to make an action plan that would be implemented out-of-group. A detailed summary of the goals, topics and activities of each session in the preadolescent curriculum is included in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

The Champ Pre-Adolescent Program

| Session Topic | Session Objectives | Parent Group Activities | Child Group Activities | Family Interaction Tasks |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Session 1: Working Together to Keep Our Kids Safe! |

|

|

|

Each family sits together

|

|

Session 2: Where Are We Going? Paperwork! |

|

|

|

|

|

Session 3: Talking and Listening To Each Other |

|

|

|

Each family sits together

|

|

Session 4: Keeping Track of Kids–Part 1 |

|

|

|

Each family sits together

|

|

Session 5: Keeping Track of Kids–Part 2 |

|

|

|

Each family sits together

|

|

Session 6: Who Can Help Us Raise Our Children? |

|

|

|

Each family sits together

|

|

Session 7: Rules Keep Kids Safe |

|

|

|

Each family sits together

|

|

Session 8: Growing Up: Talking About Puberty |

|

|

|

Each family sits together

|

|

Session 9: What We Need to Know About HIV/AIDS |

|

|

|

Each family sits together

|

|

Session 10: Growing Up: Preparing Kids for Adolescence |

|

|

|

Each family sits together

|

|

Session 11: Paperwork and More Paperwork! |

|

|

|

|

|

Session 12: A Celebration! |

|

|

|

|

FAMILY INFLUENCES ON HIV/AIDS RISK BEHAVIOR

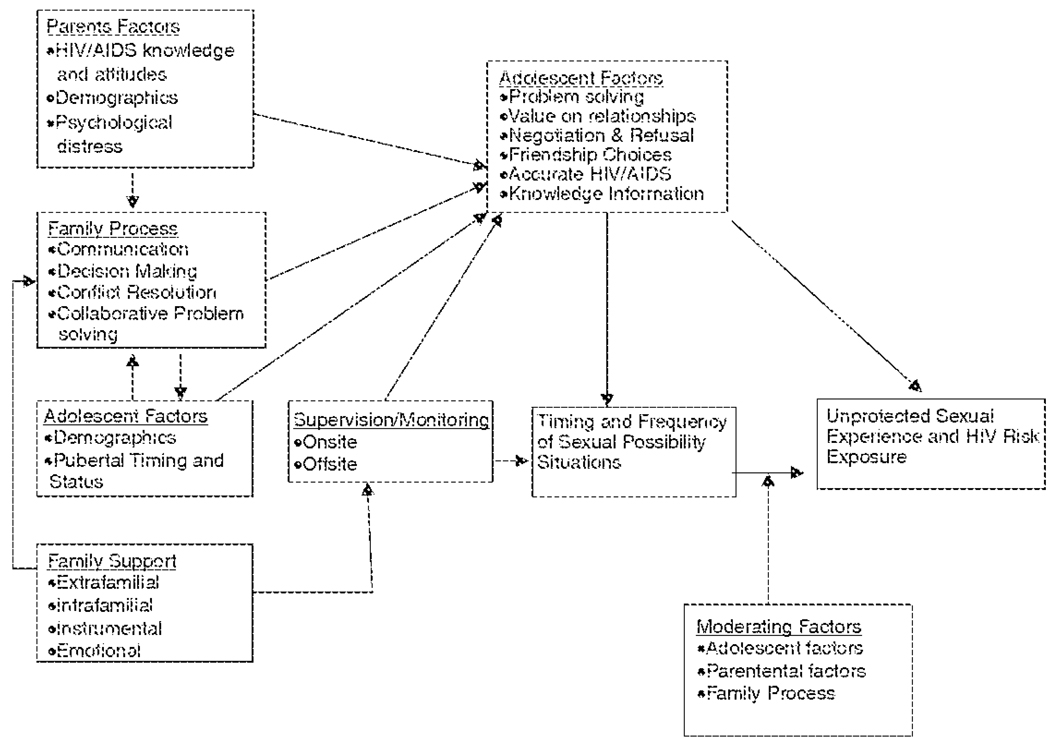

In this paper we focus on components of this conceptual model that relate to family influence on preadolescent HIV/AIDS risk exposure. Next, Figure 1 presents our conceptual model of family influences on HIV/AIDS risk behavior. Sexual possibility situations (hereafter abbreviated as SPSs), defined as private, mixed sex, unsupervised situations, represent one possible gateway to early sexual activity and HIV/AIDS risk exposure (Paikoff, 1996). As children mature into older adolescents, SPSs become more normative and developmentally appropriate as youth become interested in dating and romantic relationships. However, participation in SPSs at an early age represents a risk for younger children who are not cognitively or developmentally prepared for early sexual activity. Hence, the CHAMP intervention program encourages parents to improve their monitoring skills with the goal of reducing the number of opportunities that youth have to participate in SPSs. While the theoretical value of SPSs is clear, empirical support for the links between SPSs and actual sexual activity exists as well. DiLorio and colleagues (2004) found that SPS were associated with actual sexual behavior in a sample of 11 to 14 year old African American adolescents.

FIGURE 1.

A Conceptual Model of Family Influences on HIV/AIDS Risk Exposure

Sexual Possibility Situations and Peer Pressure

We used Situations of Sexual Possibility as our key intervention outcome and explored several key theoretical mediators addressed as targets of the intervention. At the level of the child, we investigated the role of peer pressure. As part of the intervention, the CHAMP program develops peer resistance skills in the youth. Numerous studies have demonstrated that youth who can refuse the unwanted pressure of peers are less likely to engage in risky behaviors (Billy & Udry, 1985; Keefe, 1992; Romer et al., 1993; Dahlberg, 1998; Kung & Farrell, 2000; Walker-Barnes & Mason 2001; Fuemmeler et al., 2002). We assessed how likely youth are to break off a friendship when faced with unwanted peer pressure. Since sexual risk often occurs in peer contexts, the child’s ability to refuse unwanted pressure and discontinue these friendships with pressuring peers is an important marker of the child’s assertiveness skills.

Sexual Possibility Situations and Family Processes

We also explored two elements of family process, as reported by the youth, who participated: parental control and family conflict. Parental control addresses who makes decisions in the family regarding key family issues. Paikoff et al. (1997) did not find an association between parental control and situations of sexual possibility. However, Kapungu et al. (in preparation), in a longitudinal study, found that boys of families with greater parental control were less likely to reach sexual debut in early adolescence. In terms of family conflict, McBride et al. (2003) found that both self-reported and observed family conflict at pre-adolescence, with some results moderated by pubertal development, predicted sexual debut at early adolescence. Early sexual debut has been linked to greater sexual risk because younger adolescents who are also less likely to use condoms and have greater numbers of lifetime partners (Rodrigue, Tercyak, & Lescano, 1997).

The constructs discussed here are only a portion of the key variables in the theoretical model. Each of the constructs is a component of the intervention and is hypothesized to change as a result of participation in the intervention. McKay and colleagues (2004) discuss findings related to key outcomes based on the report of parents in the same sample. Findings reveal that parents who participated in the intervention reported that they were more likely to make decisions in the family, had improvements in parental monitoring, as well as in family communication and comfort related to family communication. Hence these findings indicates the importance of increasing parents’ capacity for control and decision-making, as well as reducing family conflict so that parents may protect their developing teens. This paper builds on findings of McKay and colleagues (2004) by examining key outcomes based on the child’s report

METHODS

Participants

The CHAMP Family Program sample of youth and their families (n = 324) were identified to participate in the CHAMP Family Program at the end of the 1995/1996 school year. Youth attended one of four elementary schools, located adjacent to large, high rise subsidized housing projects and within 11 blocks of each other. All of these schools are 99% African American and over 90% poverty (as indicated by children’s qualification for free lunches). Approximately 75% of families in the community are female-headed households, and 63% of adult caregivers have not worked in the last year.

Of the 324 eligible 4th and 5th graders (92% of youth on class rosters at 4 elementary schools, all with active parent consent), 274 (85%) of their families could be located and invited to participate. We did not continue to track the remaining 15% of youth since they represented moves to other communities or whose address we were never able to determine. Approximately 73% of families located completed the entire CHAMP Family Program (n = 201). An additional 26 families completed pre/posttest assessments and some portion of the intervention (for a total of 86% of families located). Only the first three cohorts of youth and their families are included in the current study (n = 100).

Approximately 60% of the sample is female and 40% is male. Almost 76% of parents reported a family income of less than $14,000. Three quarters of adult caregivers completed high school and 8% of parent figures had attended some college. Approximately 17% of the adult caregivers are between the ages of 25 and 29 years, indicating that they were teenagers at the time of the target child’s birth.

Youth involved in the comparison group in the current study, consists of 315 non-overlapping 4th and 5th graders drawn from the same community during the 1993/1994 school year. This sample of youth and their families were involved in the CHAMP Family Study, a longitudinal examination of family and mental health factors related to HIV risk exposure during the transition to adolescence (and did not receive the preventative intervention). The longitudinal examination consisted of yearly interviews only. Of the 315 eligible youth, all parents were invited to learn more about the longitudinal study. Approximately 92% (n = 290) of parents responded to project outreach efforts. Two hundred sixty-four families (91% of contacted families) participated fully in a three-hour interview. From this sample of 4th and 5th grade children who completed questionnaires, we selected a random sample of 104 children to serve as a comparison sample. This comparison sample, which consisted of 60% girls and 40% boys, completed questionnaires with their female caregiver.

These caregivers were also primarily biological mothers as well as grandmothers, aunts and older siblings. Approximately 57% of the youth comparison sample is female and 43% is male. Approximately 60% of the families are headed by unmarried mothers. Approximately 90% of families reside in federally subsidized housing apartments and have incomes less than $14,000. Approximately 46% of adult caregivers reported completing high school or GED. Fifty-four percent of adult caregivers were employed in the last year. A comparison between the experimental and comparison samples is provided in Table 2.

TABLE 2.

Comparison of Samples

| CHAMP Family Program (n = 201) |

Comparison (n = 264) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Males | 40% | 43% |

| Females | 60% | 57% |

| Percent Female Headed Household | 73% | 60% |

| Family Income < $14,000 | 76% | 90% |

| Adult Caregiver Employed | 70% | 54% |

Measures

Frequency in Situations of Sexual Possibility

This measure is derived from a gated behavioral interview developed by Paikoff (1995) that inquires about the amount of time the pre-adolescent spends in unsupervised, mixed sex, private situations–sexual possibility situations. This scale taps how often during the week that youth find themselves in these situations of sexual possibility. An index score is created by summing across three items answered by the child: how often, how long, and how many times the child is in unsupervised situations with children of opposite sex. DiIorio et al. (in press) using an index of SPS found an alpha reliability of .66. Higher scores indicate that a child is in a situation of sexual possibility more often.

Relationship Maintenance

This scale is completed by the pre-adolescent about whether they would keep or break off a friendship under 7 situations of pressure from a friend. Pressure situations include making fun of another friend, skipping school, smoking cigarettes, drinking alcohol, etc. Each item is answered using a 4 point Likert type scale that includes (1) Definitely would break off the friendship, (2) Probably would keep the friendship, (3) Probably would break off the friendship, and (4) Definitely would break off the friendship.

Parental Control

This questionnaire, completed by the pre-adolescent, asked questions related to 17 parenting issues (e.g., chores, bedtime, friends); responses were made on a 4-point Likert scale. For each parenting issue, youth were asked whether their parents (a) tell their child exactly what to do (restrictive control), (b) discuss the issue and then have the final say (firm control), (c) discuss the issue and then the child has the final say (responsive control), or (d) leave it up to the child to decide (low control). Scores can range from 17 to 68, higher scores indicating low control. Paikoff et al. (1997) found inter-item reliability was high (alpha = .76). The scale has been used previously with diverse adolescents (Holmbeck & O' Donnell, 1991).

Average Intensity of Discussion (Family Conflict)

Average intensity of discussion between parent and child was assessed using the Issues Checklist, brief version (Holmbeck & O'Donnell, 1991; Robin & Foster, 1989). Children indicated if they had discussed 17 possible issues (i.e., curfew, homework, choice of friends) with their caregivers during the past two weeks. For each issue discussed, participants indicated how many times the issue had been discussed in the past two weeks, and how “hot” (intensity) the discussions were using a five point Likert scale, which ranged from 1 (calm) to 5 (angry). Average intensity of discussions was calculated by computing the mean of the intensity ratings for the 17 issues discussed. Total scores ranged from 17–16, with higher scores indicating greater conflict. Inter-item reliability was .77 for the child report.

RESULTS

For each variable measured, we conducted paired t-tests of the pre and post data from the intervention group. Table 3 presents the results of these analyses (n = 88). On the Parental Control scale, there was a significant change in who makes the decisions in the family, t = 2.70, p < .01, such that on average, after receiving the intervention, parents were making more decisions in their families, as opposed to the children. On the Relationship Maintenance scale, which measured the child’s response to peer pressure, there was a significant change, t = −2.53, p < .01, such that children reported after receiving the intervention, they were more likely to break off a friendship in response to peer pressure. There were no significant pre-post changes in the Family Conflict measure or in the frequency of situations of sexual possibility for the intervention group.

TABLE 3.

Pre vs. Post Comparison of Intervention Group Only

| Variable | Pre | Post | t (df) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| M (S.D.) | M (S.D.) | |||

| Family Conflict | 1.95 (0.68) | 1.98(0.77) | −0.34 (87) | ns |

| Decision Making | 1.92 (0.47) | 1.77(0.52) | 2.70 (86) | .01 |

| Relationship Maintenance | 3.68 (0.32) | 3.77 (0.26) | −2.53 (85) | .01 |

| Frequency in SSP | 0.89 (2.98) | 0.35(1.69) | 1.51 (84) | .14 |

SSP = Situations of Sexual Possibility

We next compared the post-test scores from the intervention group to scores from the comparison group. These results are summarized in Table 4. The children in the intervention group reported significantly lower scores on the Parental Control scale, t = 5.60, p < .001, suggesting that the parents in the intervention group are making more decisions in their families than the parents in the comparison group. The children in the intervention group reported that they were in situations of sexual possibility significantly less often, t = 3.22, p < .01, n = 88, than children in the comparison sample (n = 315). Interestingly, children in the intervention group reported a significantly higher level of Family Conflict, t = −2.97,p < .01, than the comparison group. There was no significant difference between the intervention and comparison groups on the Relationship Maintenance scale.

TABLE 4.

Post Intervention vs. Comparison Group

| Intervention | Comparison | t (df) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | M (S.D.) | M (S.D.) | ||

| Family Conflict | 2.03 (0.81) | 1.71 (0.79) | −2.97 (219) | .01 |

| Decision Making | 1.79 (0.53) | 2.17 (0.47) | 5.60 (219) | .001 |

| Relationship Maintenance | 3.77 (0.26) | 3.84 (0.27) | 1.77 (188) | .08 |

| Frequency in SSP | 0.35 (1.69) | 1.67 (3.74) | 3.22 (187) | .01 |

DISCUSSION

Social indicators suggest that African American adolescents are in the highest risk categories of those contracting HIV/AIDS (CDC, 2001). One potential method of curtailing HIV transmission is via strategic community prevention programs. However, for these programs to be successful they must contain three concrete programmatic features: (1) Contextual relevance; (2) Developmental-groundedness; and (3) Systemic Delivery. Because families are considered be urban youth’s best hope to grow up and survive multiple dangers in urban neighborhoods (Pequegnat & Szapocznik, 2000), centering prevention within families may ensure that youth receive ongoing support, education, and value messages that can increase their capacity to negotiate peer situations involving sex. The CHAMP Family Program not only centers its prevention efforts at the family level in order to prevent early adolescent sexual debut, it is also designed and administered within the community to ensure cultural relevance and develop unique systems of care. Moreover, CHAMP is designed to meet the needs of children at various developmental levels to ensure that they acquire appropriate and viable strategies for social problem solving and family communication.

Results from this study suggest that participation in the CHAMP Family Program was positively associated with parental decision making within the family, thereby potentially improving the influence that parents have in their children’s lives. Results also revealed that youth reported an improvement in their abilities to resist peer pressure. Both of these findings suggest that changes in two key mechanisms related to risk taking were associated with participation in the intervention. We also found that relative to a comparison group, the children in the intervention group were in sexual possibility situations less often and had parents with higher levels of parental control in their families.

LIMITATIONS

As with any quasi-experimental design, our findings may be criticized for threats to internal validity. Specifically the intervention sample may have improved over time, regardless of the intervention. To address this threat we compared the intervention sample to a comparison group of similar adolescents from the same community. We were able to avoid a lack of comparability between the samples by comparing the samples across a number of dimensions to demonstrate their multiple similarities; the children from the two groups did not differ in terms of age or gender and attended the same schools. Their parents had similar levels of education, had similar levels of income and they lived in the same neighborhoods.

IMPLICATIONS FOR HIV PREVENTION RESEARCH

These results are promising given that multiple studies have shown that adolescents who are involved with their parents and interact about high-risk behavior have been found to more successfully negotiate peer pressure social situations and resist engaging in high-risk behavior than adolescents who do not communicate with their parents (Holtzman & Rubinson, 1995; Farrell & White, 1998; Romer et al., 1994; Pick & Palos, 1995; Hutchinson & Cooney, 1998; Somers & Paulson, 2000). Communicating with their adolescents may be one of the most effective ways caregivers can protect their adolescents from making poor decisions that may impact their lives (Mueller & Powers, 1990; Holtzman & Rubinson, 1995).

By discussing possible high-risk situations and appropriate negotiation skills, parents may be able to increase the likelihood that their adolescent will implement these skills outside of the family unit. Ideally these discussions will lead to increased confidence for the adolescent and subsequent perceived self efficacy in social situations.

The multiple and co-occurring risks for urban youth underscore the need to address HIV risk holistically (Bell, Flay, & Paikoff, 2001) Future studies in the area of HIV prevention could benefit from implementing programs that embed messages and strategies specifically tailored for youth living in an urban context, many of whom are growing up in poverty-stricken communities with high levels of social toxicity, thus providing and element of contextual relevance to the inter- vention. Moreover, recognizing that urban youth face significantly different risks and challenges as they move from younger to more mature phases of adolescence requires researchers to cultivate developmentally grounded interventions that prepare youth to recognize risk situations, as well as to negotiate situations according to their current level of skills (Hains & Herrman, 1989). Finally, researchers should design interventions that will be delivered in the proximal systems in which youth decisions unfold. For most youth these include family and peer systems. More specifically, interventions that actively involve family members and strategies that enhance protective family processes are needed.

It is important to note that results indicating greater levels of family conflict in this study’s intervention group relative to the comparison group were unexpected. We speculate that a finer analysis of this finding might indicate that the overall level of conflict among the intervention families may have been raised because they were addressing difficult issues more frequently than the comparison sample.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the following persons: Emily Folk, Tariq Qureshi and Michelle Ernst for their assistance with the data. The authors are grateful to our community facilitators and mental health interns who tirelessly collected the data and conducted the group sessions. Thanks especially to the CHAMP children and parents who gave their time by participating.

Funding from the National Institute of Mental Health (R01 MH 63662) and the W. T. Grant Foundation is gratefully acknowledged. Dorian Traube is currently a pre-doctoral fellow at the Columbia University School of Social Work supported by a training grant from the National Institutes of Mental Health (5T32MH014623-24).

Footnotes

COPYRIGHT NOTICE: The copy law of the United States (Title 17 U.S. Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted material. Under certain conditions specified in the law, libraries and archives are authorized to furnish a photocopy or other reproduction. One of these specified conditions is that the photocopy or reproduction is not to be “used for any purpose other than private study, scholarship or research”. Note that in the case of electronic files, “reproduction” may also include forwarding the file by email to a third party. If a user makes a request for, or later uses a photocopy or reproduction for purposes in excess of “fair use”, that user may be liable for copyright infringement. USC reserves the right to refuse to process a request if, in its judgment, fulfillment of the order would involve violation of copyright law. By using USC’s Integrated Document Delivery (IDD) services you expressly agree to comply with Copyright Law.

REFERENCES

- Baptiste D, Paikoff P, McKay M, Madison-Boyd S, Bell C, Coleman D The CHAMP Board. Behavior Modification. 2. Vol. 29. CA: Sage; 2004. Collaborating with an urban community to develop an HIV/AIDS prevention program for Black youth and families; pp. 370–416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell CC, Flay B, Paikoff R. Strategies for Health Behavioral Change. In: Chunn J, editor. The Health Behavioral Change Imperative: Theory, Education, and Practice in Diverse Populations. New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers; 2002. pp. 17–40. [Google Scholar]

- Billy JOG, Udry JR. The influence of male and female best friends on adolescent sexual behavior. Adolescence. 1985;XX(77):21–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control. Atlanta: Center for Infectious Disease Control; HIV/AIDS surveillance report. 2001

- Dahlberg LL. Youth violence in the United States: Major trends, risk factors, and approaches. American Journal of Prevention Medicine. 1998;14(4):259–272. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(98)00009-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiLorio C, Dudley WN, Soet JE, McCarty F. Sexual possibility situations and sexual behaviors among young adolescents: The moderating role of protective factors. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2004;35(6):11–20. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2004.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuemmeler BF, Taylor LA, Metz AEJ, Brown RT. Risk-taking and smoking tendency among primarily African American school children: Moderating influences of peer susceptibility. Journal of Clinical Psychology and Medical Settings. 2002;9(4):323–330. [Google Scholar]

- Hains AA, Herrman LP. Social cognitive skills and behavioral adjustment of delinquent adolescents in treatment. Journal of Adolescence. 1989;12(3):323–328. doi: 10.1016/0140-1971(89)90082-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutchinson MK, Cooney TM. Patterns of parent-teen sexual risk communication: Implications for intervention. Family Relations. 1998;47(2):185–194. [Google Scholar]

- Holmbeck GN, O’Donnell K. Discrepancies between perceptions of decision making and behavioral autonomy. New Directions for Child Development. 1991;51:51–69. [Google Scholar]

- Holtzman D, Rubinson R. Parent and peer communication effects on AIDS-related behavior among U.S. high school students. Family Planning Perspectives. 1995;27(6):235–247. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Illinois Department of Health. [Retrieved 8/12/04];2001 http://www.idph.state.il.us/

- Kapungu CK, Holmbeck GN, Paikoff RL. Longitudinal association between parenting practices and early sexual risk behaviors among urban African American adolescents: The moderating role of gender. (in preparation) [Google Scholar]

- Keefe K. Perceptions of normative social pressure and attitudes toward alcohol use: changes during adolescence. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1992 January;:46–54. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1994.55.46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kung EM, Farrell AD. The role of parents and peers in early adolescent substance use: an examination of mediating and moderating effects. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2000;9(4):509–528. [Google Scholar]

- Madison SM, McKay MM, Paikoff RL, Bell CC. Basic research and community collaboration: Necessary ingredients for the development of a family-based HIV prevention program. AIDS Education and Prevention. 2000;12:281–298. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McBride CK, Paikoff RL, Holmbeck GN. Individual and familial influences on the onset of sexual intercourse among urban African American adolescents. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2003;71(1):159–167. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.71.1.159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKay M, Paikoff R, Baptiste D, Bell C, Coieman D, Madison S, McKinney L CHAMP Collaborative Board. “Family-level impact of the CHAMP Family Program: A community collaborative effort to support urban families and reduce youth HIV risk exposure.”. Family Process. 2004;43(1):79–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.2004.04301007.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKay M, Baptiste D, Coleman D, Madison S, Paikoff R, Scott R. Preventing HIV risk exposure in urban communities: The CHAMP Family Program. In: Pequegnat W, Szapocznik Jose, editors. Working with families in the era of HIV/AIDS. California: Sage Publications; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Mueller KE, Powers WG. Parent-child sexual discussion: perceived communicator style and subsequent behavior. Adolescence. 1990;XXV(98):469–482. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paikoff RL, McKay M. The Chicago HIV Prevention adolescent mental health project (CHAMP) family-based intervention. National Institute of Mental Health, Office on AIDS and William. T. Grant Foundation; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Paikoff RL, Parfenoff SH, Greenwood GL, McCormick A. Parenting, parent-child relationships, and sexual possibility situations among urban African American preadolescents: Preliminary findings and implications for HIV prevention. Journal of Family Psychology. 1997;11:11–22. [Google Scholar]

- Paikoff RL. Early heterosexual debut: Situations of sexual possibility during the transition to adolescence. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 1996;65:389–401. doi: 10.1037/h0079652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pequegnat W, Szapocznik J, editors. Working with Families in the Era of HIV/AIDS. CA: Sage publications; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Pick S, Palos PA. Impact of the family on the sex lives of adolescents. Adolescence. 1995;30(119):667–675. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robin AL, Foster SL. Negotiating parent-adolescent conflict. New York: Guilford Press; 1989. Self-report measures; pp. 295–328. [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigue JR, Tercyak KP, Lescano CM. Health promotion in minority adolescents: emphasis on sexually transmitted diseases and the human immunodeficiency virus. In: Wilson DK, Rodrigue JR, Taylor WC, editors. Health-promoting and health-compromising behaviors among minority adolescents. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 1997. pp. 87–105. [Google Scholar]

- Romer D, Black M, Ricardo I, Feigelman S, Kalijee L, Galbraith J, et al. Social influences on the sexual behavior of youth at risk for HIV exposure. American Journal of Public Health. 1993;84(6):977–985. doi: 10.2105/ajph.84.6.977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tolan PH, Gorman-Smith D, Henry DB. The developmental ecology of urban males’ youth violence. Developmental Psychology. 2003;39(2):274–291. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.39.2.274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker-Barnes CJ, Mason CA. Perceptions of risk factors for female gang involvement among African American and Hispanic women. Youth and Society. 2001;32(3):303–326. [Google Scholar]