Abstract

Objective:

A growing body of literature suggests that intimate partner violence (IPV) occurs within same-sex relationships and that members of the Lesbian Gay Bisexual Transgender (LGBT) community face a number of unique challenges in accessing IPV-related services. This paper examines the use of an online survey, marketed through a popular social networking site, to collect data on the experience and perpetration of IPV among men who have sex with men (MSM) in the United States.

Methods:

Internet-using MSM were recruited through selective placement of banner advertisements on MySpace.com. Participants were eligible for the baseline survey if they were males ≥ 18 years of age, and reported at least one male sex partner in the last 12 months. In total 16,597 men responded to the ad, of which 11,681 were eligible for the study, and 5,602 completed the questionnaire; 543 men completed the follow-up survey, which included questions on the experience and perpetration of IPV. The final analysis sample was 402.

Results:

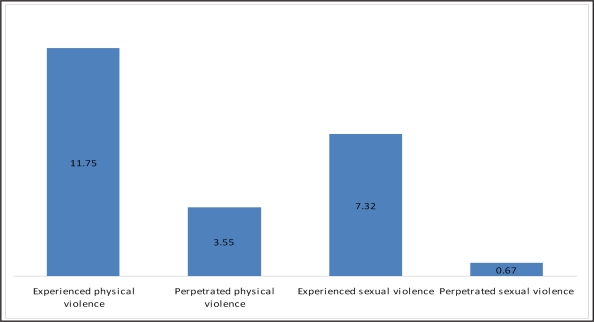

The prevalence of violence among the sample was relatively high: 11.8% of men reported physical violence from a current male partner, and about 4% reported experiencing coerced sex. Reporting of perpetration of violence against a partner was generally lower, with approximately 7% reporting perpetrating physical violence and less than 1% reporting perpetration of sexual violence.

Conclusion:

The results presented here find lower levels of experiencing both physical and sexual IPV than have been shown in previous studies, yet show relatively high levels of reporting of perpetration of IPV. Collecting IPV data through surveys administered through social networking sites is feasible and provides a new opportunity to reach currently overlooked populations in IPV research.

INTRODUCTION

Based on United States Census data, approximately 700,000 same-sex couples live together in the U.S.1 In many states, same-sex partnerships are not recognized legally, and thus couples may have limited or no access to traditional intimate partner violence (IPV) safeguards.2,3 In the scientific literature the most common depiction of intimate partner violence (IPV) involves a male batterer and a female victim. However, a growing body of literature suggests that IPV occurs within same-sex relationships and that members of the Lesbian Gay Bisexual Transgender (LGBT) community face a number of unique challenges in accessing IPV-related services.4,5 Additionally, a number of methodological issues have hampered research into IPV among LGBT individuals.6 These include a tendency to focus on lesbians, often to the exclusion of gay and bisexual men, a focus on child abuse and hate crimes to the exclusion of IPV, and a failure to use representative samples. The latter is due to the problems researchers have faced in recruiting representative samples, and many researchers have thus relied upon convenience samples recruited through LGBT publications, events and organizations.7,8 Moreover, victims of same-sex IPV may be hesitant to seek help, due to internalized or institutionalized homophobia, the nature of the abuse itself, or a perceived lack of useful resources resulting in underreporting of abuse.6,9–12 The existing evidence suggests that IPV affects approximately one-quarter to one-half of all same-sex relationships.5,8,9,13 These rates are similar to estimates of abuse in heterosexual relationships.9 Physical abuse seems to occur in a significant portion of abusive same-sex relationships. Elliot14 and De Vidas15 suggest that between 22–46% of lesbians have been in relationships featuring physical violence. McClennen et al.4 found that participants were often physically struck by their partners, and were coerced into substance abuse. Greenwood et al.16 reported that 22% of a sample of men who had sex with men (MSM) had been subject to physical abuse from an intimate partner. This paper examines the use of an online survey, marketed through a popular social networking site, to collect data on the experience and perpetration of IPV among self-identifying gay and bisexual men in the U.S. Online surveys have the potential to surmount many of the recruitment issues that have hampered previous attempts to quantify IPV among same-sex populations. The current study adds to the existing body of evidence on IPV among same-sex couples by using a larger sample size than has been used in previous studies, and by demonstrating how social networking sites can be used to collect thus type of data.

METHODS

We recruited internet-using MSM through selective placement of banner advertisements on MySpace.com. The ads displayed men of differing races and ages, in order to attract participants from a range of backgrounds. During the recruitment period, advertisements were displayed to MySpace members based on self-reported demographic profile information. Exposures were made at random times of day to males ≥ 18 years logging into MySpace whose profile indicated a residence in the U.S. and who reported their sexual orientation as gay, bisexual, or unsure. Participants who clicked through the banner advertisements were taken to an internet-based survey. Six banner advertisements were used, all with similar text and graphical design. Two of the advertisements presented a white male model, two presented a black male model, and two presented an Asian male model. Participants referred to the survey site after clicking through were first screened for eligibility. Participants were eligible for the baseline study survey if they were males ≥ 18 years of age and reported at least one male sex partner in the last 12 months. Eligible participants were provided informed consent documents, and consenting participants were passed into an online survey. In the survey, participants were asked for relevant demographic information as well as questions about the use of the internet to meet sex partners, recent sexual risk behaviors, use of technology, HIV testing history, and interest in specific, new HIV prevention interventions. Participants were eligible for a follow-up study if in addition to the baseline eligibility criteria, they were ≤ 35 years of age, reported their race as white (non-Hispanic), Black (Hispanic or non-Hispanic), or who reported their ethnicity as Hispanic, and did not report being HIV sero-positive during the baseline survey. The follow-up study was restricted to men < 35, as one of the aims of the larger project was to look at HIV risk among young MSM. In total 16,597 men responded to the ad, of whom 11,681 were eligible for the study, and 5,602 completed the questionnaire; 543 men completed the follow-up survey. The follow-up survey included questions on the perpetration and experience of IPV. Men were asked if they had ever been physically hurt by their current male partner (“In the last 12 months has any partner been physically violent to you? This includes pushing, holding you down, hitting you with his fist, kicking, attempting to strangle, attacking with a knife, gun or other weapon?”), and if their current male partner had ever used physical force to force them to have sex when they did not want to (“In the last 12 months has any partner ever forced you to have sex when you were unwilling?”). Men were also asked if they had perpetrated either physical or sexual violence against any male partner. The analysis examines the reporting of both the experience and perpetration of physical and sexual IPV among a final sample of 402 MSM with complete data for all questions, and examines differences in the reporting of IPV across background characteristics. The research was reviewed and approved by Emory’s Institutional Review Board.

RESULTS

The final sample was predominantly young (18–24), Caucasian and with some college education (Table 1). The majority self-identified as homosexual, reported themselves to be HIV negative, although a large percentage reported recent unprotected anal sex. Figure 1 shows the prevalence of violence among the sample: 11.8% of men reported physical violence from a male partner, while around 4% reported experiencing coerced sex. Reporting of perpetration of violence was generally lower, with approximately 7% reporting perpetrating physical violence towards a male partner and less than 1% reporting perpetration of sexual violence towards a male partner. Table 1 shows variations in the reporting of experience and perpetration of physical and sexual IPV. The only significant variation in the reporting of experiencing physical IPV was across recent high-risk sex, with men who reported recent unprotected anal sex more likely to also report experiencing physical IPV. The reporting of sexual IPV experience varied significantly by age, with higher levels in the 18–24 and 30–35 age groups, and was again highest among men who reported recent unprotected anal sex. Reporting of perpetrating physical IPV was significantly higher among older men and among men who reported not having a recent STD test, while the reporting of perpetrating sexual IPV was higher among Black and bisexual men.

Table 1.

Background characteristics and prevalence of IPV

| % | % reporting experiencing physical IPV | % reporting experiencing sexual IPV | % reporting perpetrating physical IPV | % reporting perpetrating sexual IPV | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AGE | |||||

| 18–24 | 68.07 | 11.07 | 4.56 | 5.21 | 0.98 |

| 25–29 | 20.84 | 14.89 | 0 | 12.77 | 0 |

| 30–35 | 11.09 | 10 | 4 | 10 | 0 |

| RACE | |||||

| Hispanic | 37.47 | 15.38 | 3.55 | 8.88 | 0.59 |

| Black/ African American | 14.86 | 5.97 | 2.99 | 5.97 | 2.99 |

| White/ Caucasian | 47.67 | 10.07 | 3.72 | 6.51 | 0 |

| EDUCATION | |||||

| Less than high school/General Educational Development | 4.66 | 14.29 | 4.76 | 4.76 | 0 |

| High School/General Educational Development | 26.83 | 11.57 | 5.79 | 9.09 | 0.83 |

| Some college or higher | 68.51 | 11.65 | 2.59 | 6.8 | 0.65 |

| SEXUAL IDENTITY | |||||

| Bisexual | 19.07 | 9.3 | 3.49 | 4.65 | 2.33 |

| Homosexual | 80.93 | 12.33 | 3.56 | 7.95 | 0.27 |

| SEXUALLY TRANSMITTED DISEASE TEST IN LAST 12 MONTHS | |||||

| Yes | 38.58 | 12.07 | 4.02 | 5.42 | 0.57 |

| No | 61.42 | 11.60 | 3.25 | 10.34 | 0.72 |

| HUMAN IMMUNODEFICIENCY VIRUS SERO-STATUS | |||||

| Negative | 67.18 | 12.87 | 3.3 | 7.59 | 0.33 |

| Positive | 3.77 | 17.65 | 5.88 | 5.88 | 0 |

| Untested | 29.05 | 8.4 | 3.82 | 6.87 | 1.53 |

| LAST SEX WAS UNPROTECTED ANAL SEX | |||||

| Yes | 34.59 | 16.03 | 5.77 | 5.77 | 0 |

| No | 65.41 | 9.49 | 2.37 | 8.14 | 1.02 |

| NUMBER OF MALE SEX PARTNERS LAST 12 MONTHS | |||||

| None | |||||

| One | |||||

| Two-Five | |||||

| Six-Ten | |||||

| Eleven Plus | |||||

| FREQUENCY OF ATTENDING BARS | |||||

| Once a month or less | 74.94 | 10.65 | 2.96 | 7.4 | 0.59 |

| About once per week | 19.73 | 20.83 | 5.62 | 6.74 | 0 |

| About once per month | 5.32 | 13.48 | 4.17 | 8.33 | 1.12 |

Figure 1.

Reporting of experience and perpetration of physcial and sexual intimate partner violence among gay and bisexual men (n=402).

DISCUSSION

A small number of studies have suggested that the prevalence of IPV among same-sex couples in the U.S. is similar to that seen in heterosexual couples.16 Harms17 conducted a prevalence study that focused on gay and bisexual men, finding that 26% of respondents reported that they had experienced physical violence in their last relationship. The results presented here find lower levels of both physical and sexual IPV than have been shown in previous studies, yet show relatively high levels of reporting of perpetration of IPV. However, such previous studies have relied on convenience samples of clinic-based populations. The recruitment of LGBT individuals into studies of IPV has posed a challenge to researchers, due primarily to perceived difficulties in disclosing sexual orientation; as such, many previous studies have used convenience samples recruited through LGBT venues and publications.7 The results presented here demonstrate the feasibility of collecting IPV data through surveys administered via social networking sites, providing a new opportunity to reach currently overlooked populations in IPV research. The results also demonstrate some interesting variations in both the experience and perpetration of violence. Reporting of high-risk sex was associated with reporting of higher levels of experience of both physical and sexual IPV. This result likely reflects an association between risk-taking and vulnerability to IPV: gay men who report lower levels of victimization have been shown to also report lower levels of substance abuse, suicidality, and sexual risk-taking behaviors.18 The results show higher levels of perpetration of sexual IPV among Black and bisexual men. While these results may reflect an association between minority stress and acts of violence, the overall number of men reporting perpetrating sexual violence was low and these associations should be treated with caution.

LIMITATIONS

The key limitations to the present results are small sample size and possible selection bias in both the decision to complete the questionnaire and the decision to answer the questions on IPV. Research on IPV among same-sex partners remained virtually non-existent until the 1990s, when the emergence of the HIV epidemic increased focus on the LGBT community.19 Kaschak11 refers to the “double closet” that surrounds IPV in same-sex relationships: the dual burden of shame and silence surrounding both the discussion of IPV and the discussion of sexuality; hence, it is possible that IPV may be under-reported.

CONCLUSION

The results presented here demonstrate high levels of IPV among gay and bisexual men and illustrate how an online survey coupled with social networking sites can be used to collect data on sensitive public health issues such as IPV. There is clearly a need for further research into issues surrounding IPV in same-sex male relationships, a population vulnerable to high levels of IPV, and to understand the complex relationships that exist between IPV, risk-taking and identity. Such information is vital for the development of effective interventions to reduce violence and improve health, in particular sexual health, among MSM in the U.S.

Footnotes

Reprints available through open access at http://escholarship.org/uc/uciem_westjem

Conflicts of Interest: By the WestJEM article submission agreement, all authors are required to disclose all affiliations, funding sources, and financial or management relationships that could be perceived as potential sources of bias. The authors disclosed none. This work was supported by the Emory Center for AIDS Research (P30 AI050409).

REFERENCES

- 1.Gay Demographics Census information on gay and lesbian couples. 2000. Available at: http://www.gaydemographics.org. Accessed October 17, 2006.

- 2.Aulivola M. Outing domestic violence: Affording appropriate protections to gay and lesbian victims. Family Court Review. 2004;42:162–77. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barnes PG. It’s just a quarrel. J of the American Bar Association. 1998;84:24–5. [Google Scholar]

- 4.McClennen JC. Domestic violence between same-gender partners recent findings and future research. J Interpers Violence. 2005;20(2):149–54. doi: 10.1177/0886260504268762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McClennen JC, Summers B, Vaugh C. Gay men’s domestic violence: Dynamics, help-seeking behaviors, and correlates. J Gay Lesbian Soc Serv. 2002;14(1):23–49. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Balsam KF, Fothblum ED, Beauchaine TP. Victimization over the life span: A comparison of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and heterosexual siblings. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2005;74(3):477–87. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.3.477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Halpern CT, Young ML, Waller MW, et al. Prevalence of partner violence in same-sex romantic and sexual relationships in a national sample of adolescents. J Adolesc Health. 2004;35:124–31. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2003.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Burke TW, Jordan ML, Owen SS. A cross-national comparison of gay and lesbian domestic violence. J Contemp Crim Justice. 2002;18:231–56. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Alexander CJ. Violence in gay and lesbian relationships. J Gay Lesbian Soc Serv. 2002;14(1):95–8. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Browning C. Silence on same-sex partner abuse. Alternate Routes. 1995;12:95–106. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kaschak E. Intimate betrayal: Domestic violence in lesbian relationship. Women and Therapy. 2001;23(3):1–5. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Peterman LM, Dixon CG. Domestic violence between same-sex partners: Implications for counseling. J Couns Dev. 2003;81(1):40–7. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pitts EL. Domestic violence in gay and lesbian relationships. Gay and Lesbian Medical Association Journal. 2000;4:195–6. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Elliott P. Shattering illusions: Same-sex domestic violence. J Gay Lesbian Soc Serv. 1996;4(1):1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 15.De Vidas M. Childhood sexual abuse and domestic violence: A support group for Latino gay men and lesbians. J Gay Lesbian Soc Serv. 1999;10(2):51–68. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Greenwood GL, Relf MV, Huang B, et al. Battering victimization among a probability-based sample of men who have sex with men. Am J Public Health. 2002;92:1964–9. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.12.1964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Harms B. Domestic violence in the gay male community. 1995. Unpublished master’s thesis, San Francisco State University, Department of Psychology.

- 18.Bontempo DE, D’Augelli AR. Effects of at-school victimization and sexual orientation on lesbian, gay or bisexual youths’ health behavior. J Adolesc Health. 2002;30(5):364–74. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(01)00415-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Renzetti CM. Violent betrayal: Partner abuse in lesbian relationships. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1992. [Google Scholar]