Abstract

Objectives:

Internet usage has increased in recent years resulting in a growing number of documented reports of cyberbullying. Despite the rise in cyberbullying incidents, there is a dearth of research regarding high school students’ motivations for cyberbullying. The purpose of this study was to investigate high school students’ perceptions of the motivations for cyberbullying.

Method:

We undertook an exploratory qualitative study with 20 high school students, conducting individual interviews using a semi-structured interview protocol. Data were analyzed using Grounded Theory.

Results:

The developed coding hierarchy provides a framework to conceptualize motivations, which can be used to facilitate future research about motivations and to develop preventive interventions designed to thwart the negative effects of cyberbullying. The findings revealed that high school students more often identified internally motivated reasons for cyberbullying (e.g., redirect feelings) than externally motivated (no consequences, non-confrontational, target was different).

Conclusion:

Uncovering the motivations for cyberbullying should promote greater understanding of this phenomenon and potentially reduce the interpersonal violence that can result from it. By providing a framework that begins to clarify the internal and external factors motivating the behavior, there is enhanced potential to develop effective preventive interventions to prevent cyberbullying and its negative effects.

INTRODUCTION

Cyberbullying has been defined as a type of bullying that involves the use of communication technologies.1,2 Like traditional bullying, it is intentional and repetitive.3 Unlike in traditional bullying, researchers have not agreed that an imbalance of power is a necessary component.4 We identify the behavior’s unique characteristics as 1) the cyberbullies may be anonymous; 2) the perpetrators and targets are disassociated from the physical and social cues of a cyberbullying incident; and 3) adults may feel less empowered to intervene due to the role of technology.3 Examples of cyberbullying include sending harassing texts, instant messages, or e-mails.5

Researchers have begun to investigate motivations for cyberbullying.2,6 Two common and inter-related motivations include anonymity and the disinhibition effect.3,5–10,12,13 Mason described how anonymity breeds disinhibition due to the distance provided by electronic communication, normal self control can be lost or greatly reduced for potential bullies. Thus, anonymity can protect adolescents from the consequences of their actions in cyberspace.6,8 Some adolescents may feel free to do and say things they would never do in person.6,7 Raskaukas and Stoltz10 stated that cyberbullies were physically and emotionally removed from their victims; therefore, they did not experience the impact of their actions (i.e., disinhibition effect).

Additional motivations include homophobia, racial intolerance, and revenge.1,2,14 Adolescents reported engaging in cyberbullying because they gained satisfaction or pleasure from hurting their victims.1,2,8 While some cyber-perpetrators reported victimizing targets in order to feel better about themselves,10 others cyberbullied because the perpetrators believed they were provoked by their victims2 and sought revenge.1,4,12 In addition, some cyberbullies may torment their victims because they dislike the person1 or are jealous of them.8 Further, adolescents may cyberbully just “for fun.”9,11 This motivation differs from gaining pleasure by hurting others because adolescents who bully just for entertainment may not be concerned about whether or not their targets are hurt.

Rationale for Study

Despite preliminary efforts to investigate motivations for cyberbullying,1,2 there is a dearth of information on this topic,15 particularly among high school populations.16 The purpose of this study was to investigate high school students’ perceptions of the motivations for cyberbullying. We used qualitative methodology to provide an in-depth understanding of this phenomenon from the adolescents’ perspective.17

METHOD

Participants

Our research team used convenience, targeted, and snowball sampling techniques.16 Criteria for inclusion in this study required participants to be enrolled in high school and to have experience with technology. Recruitment procedures involved displaying flyers and daily public announcements. The sample was comprised of 20 students from one suburban high school. Their ages ranged from 15 to 19 [mean (M) = 18; standard deviation (SD) = 1.05] with grade levels from 10–12. The participant sample was ethnically diverse, including: 40% African American; 30% Caucasian; 15% Hispanic; 5% Asian; 5% Trinidadian; and 5% Middle Eastern. The gender breakdown was 35% female and 65% male. Ninety percent of the participants used a cell phone, 100% had a computer at home, 100% had internet access at home, and 90% reported having a social networking site profile. Participants reported four hours of daily technology usage.

Procedures and Instrumentation

A semi-structured individual interview format allowed the researchers to further investigate topics as necessary.18 Eight questions (e.g., “What contributes to threatening electronic communication?”) were asked to each student with follow-up questions (e.g., “What are the sender’s motivations?) posed as needed. Please contact the author for a copy of the interview protocol. Students age 18 and older signed consent forms prior to participating in the interview. Participants younger than 18 returned a signed parental consent form and completed an assent form prior to the interview. Students completed a demographic form on age, grade level, ethnicity and technology use. The one-on-one interviews ranged from 45 to 90 minutes. All forms and procedures were approved by the university Institutional Review Board.

Data Analysis

The students’ responses were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim. The researchers imported the transcriptions into Atlas-Ti 5.0, a software program designed for the management of qualitative data. Grounded theory20 was used due to the exploratory nature of this study and the limited literature available regarding the motivations for cyberbullying. The sample size of 20 was consistent with the recommended number of participants for studies using in-depth interviews and grounded theory.21

The research team developed the coding manual using an inductive-deductive process.22 Inductive coding involved the identification of codes from the current data set to develop an informed coding manual. Deductive coding used preexisting data, research, or theory to develop codes. A second researcher with expertise in the content area of cyberbullying, reviewed the coding manual, discussed disagreements to clarify definitions, and identified exemplar quotes. Once the coding manual was finalized, researchers independently coded interviews to establish inter-rater reliability (IRR).23 IRR is defined as the level of agreement among coders on identifying codes and subcodes within the interviews. In this study, researchers defined blocks for coding as question-and-answer responses. The researchers reached 95% IRR and discussed coding disagreements until 100% consensus was obtained. Coders determined that theoretical saturation20 had been achieved once information redundancy17 occurred. Researchers maintained an audit trail, which involved maintaining the raw records of data analysis.17

RESULTS

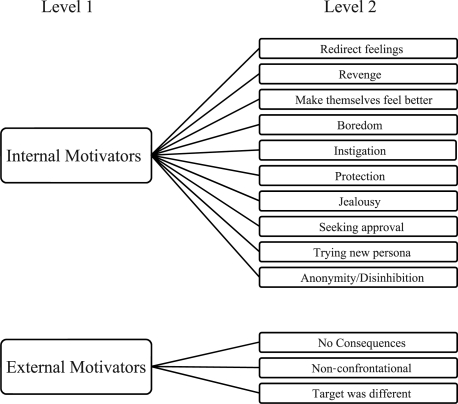

Level one codes (internal motivations, external motivations) emerged regarding high school students’ perceived motivations for cyberbullying (Figure 1). We identified level two codes under each level one code. Each code will be defined and presented with illustrative quotations from the students.

Figure 1.

Coding hierarchy

Internal Motivations

The level one theme, internal motivations, described high school students’ motivations for bullying that were perceived to be influenced by the cyberbully’s emotional state. There were ten level two codes (redirect feelings, revenge, make themselves feel better, boredom, instigation, protection, jealousy, seeking approval, trying out a new persona, anonymity/disinhibition effect) categorized as internal motivations.

The level two code, redirect feelings, described a motivation that involved previous hurtful experiences. The cyberbully may have been bullied or hurt in the past and in response bullied an innocent person online as a motivation to take their feelings out on someone else other than the perpetrator. A student stated: “You know, people have been doing it to me for so long, I deserved to be able to do it to someone.”

The level two code, revenge, described situations in which the cyberbully was provoked or angered and wanted to get back at the perpetrator. This code was different from redirect feelings because the cyberbully is going after the specific person who “wronged them” to feel better, rather than randomly targeting anyone vulnerable. A student admitted to cyberbullying, stating “I was really angry and he was not nice to me and he deserved it.”

The level two code, make themselves feel better, was defined as when the perpetrator cyberbullies someone else in an attempt to make themselves feel better. This code was differentiated from redirect feelings because the cyberbully may or may not have been hurt in the past and from revenge because the person may not have been provoked. One student stated, “Personally, that’s what I think, that’s why anybody tears a person down, to make themselves feel better.”

The level two code, boredom, was characterized by the fact that the cyberbully was motivated to victimize others in an effort to fill time or create entertainment. A student described that someone may be “bullying because they have nothing better to do.” Another student talked about youth online and how “they have nothing better to do than to go on the web, on a web video and just talk bad about it.”

The level two code, instigation, was defined as the use of cyberbullying to provoke a response out of someone else, sometimes with no specific reason given in order to feel better. One student reported that when a person that “…post[s] something like that [a bad rumor], like on a bulletin, they want someone to talk to.” Occasionally a student may cyberbully in response to events outside of the internet.

In the level two code, protection, the perpetrator was motivated to cyberbully others to be the toughest person and avoid being picked on by others. This student stated that “growing up in a rough part of town, they have been the predator of the area and that’s the only way they know how to survive so they prey on other people.”

The level two code, jealousy, was used when the person was motivated to bully someone else out of envy or resentment. One student reported that he talked to a girl whose boyfriend then became jealous. The student said “he [the boyfriend] gets jealous and says it all through MySpace.”

The level two code, seeking approval, was defined as cyberbullying to gain approval or attention. For example, cyberbullies may bully others to impress their friends. One student reported that cyberbullies “want attention. They crave the attention, which is why they are arguing over something that’s so little and petty like that. In my opinion I guess it’s making them feel better to hear their friends’ opinions.”

The level two code, Trying out a new persona, was defined as wanting to represent himself or herself in a different way in cyberspace than he or she may be perceived in real life (e.g., tougher, cooler). In one example, a student stated:

I was just trying to seem bad and would never consider doing something like that to anyone, but it’s like I was really pissed off and I was like you ever say anything like that about me again I will kill you. It’s so funny to think about now.

The level two code, anonymity/disinhibition effect, was the final code for internal motivations. These two motivations were combined since we found that the ability to be anonymous has a direct effect on feelings of disinhibition. In Anonymity, either the cyberbully may not know his online victim or the perpetrator did not reveal his identity to the cybervictim. In the disinhibition effect the cyberbully feels that she can say or do things that she may not do face to face. A student described the anonymity/disinhibition effect:

If this person probably doesn’t even know me then they are not going to know who is saying those things about them, so they are probably going to have less inhibiting from saying more and doing more.

External Motivations

The level one code external motivations, was defined as the reasons for cyberbullying provoked by the characteristic of the cybervictim or by something specific to the situation. Three level two codes (no consequences, non-confrontational, target was different) were categorized as external motivations.

In the level two code, no consequences, the cyberbully feels that he or she can get away with cyberbullying without fear of ramifications, physical retaliation from the victim, a permanent consequence (e.g., jail time), or witnessing an emotional reaction from the victim. Examples included a student quoted saying, “Well, I don’t know the person and they’re not going to try to come beat me up if I say this to them. So I’ll say whatever I want to.”

The level two code, non-confrontational was identified when a cyberbully did not want to have a face-to- face encounter with the victim or expressed fear of actually facing the person. One student stated, “because they [cyberbullies] don’t like the confrontation.”

The level two code, target was different, referred to a cyberbullying motivation based on the victim appearing different, having a negative reputation, or standing out in a way that the cyberbully perceived as negative. When asked why cyberbullying happens, a student stated, “because somebody doesn’t like somebody else because the way they look or what people say about them.”

DISCUSSION

An important contribution of this study was the finding that high school students reported a range of internal and external motivations for cyberbullying (Figure 1). This illustration provides a framework to conceptualize motivations that may be useful for guiding future research and to develop preventive interventions designed to thwart the negative effects of cyberbullying. In this study internal motivations were associated with the perpetrators’ emotional states and external motivations were derived from factors specific to the situation or the target. This information may be helpful for adults working with perpetrators in developing preventive interventions to address the emotional state and internal needs (e.g., to feel better) of the cyberbully, as well as focusing on external motivators.

A significant finding was that the students in this study reported internal motivations with greater frequency than external motivations. In addition, although the anonymity/disinhibition effect was confirmed as a motivation for cyberbullying, it was mentioned less often than other internal motivations. This finding was interesting due to the emphasis in the literature on anonymity as a primary motivation for perpetrators.3,5–10,12,13 Further research is needed to investigate the reasons for these findings to enhance the understanding of motivations and to develop ideas about how adults and students can effectively intervene to prevent cyberbullying, particularly for vulnerable populations [e.g., lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender youth (LGBT)].

Another unique finding of this study was the discovery of motivations for cyberbullying not reported in the current literature (i.e., protection) or were not explicated in prior research (i.e., redirect feelings). For example, redirect feelings in this study emphasized the need of the perpetrator to release negative feelings rather than targeting a victim based on target characteristics. Protection was defined as the cyberbully wanting to protect himself/herself from being hurt so the perpetrator targeted others. Future research is needed to replicate and extend these findings.

LIMITATIONS

Because this was an exploratory study, future research is needed to continue to develop an understanding of the motivations for cyberbullying among high school students. The current sample included cyberbullies, cybervictims and bystanders. Future research should interview cyberbullies to confirm the initial findings from this study. The small sample from one suburban high school in the southeastern U.S. limits the generalizability of these findings and suggests the need for research to broaden the population of respondents and to include those from rural and urban settings, those with a wider age range, and those from diverse regions in the U.S. Males (65%) were overrepresented in this sample, prohibiting data analysis by gender. Future research is needed to systematically evaluate gender differences and similarities in the motivations for cyberbullying. Although this sample included heterosexual and gay students, it would be important for researchers to interview LGBT youth regarding their experiences with and their perceived motivations for cyberbullying. As the database about the motivations for cyberbullying continues to grow there will be a stronger basis for developing ideas for research about treatment and prevention of this behavior.

This study made several contributions to the literature regarding high school students’ motivations for cyberbullying that should promote greater understanding and potentially help reduce injury associated with the interpersonal violence that can result from cyberbullying. By providing a framework that begins to explicate the internal and external factors that may motivate cyberbullying, we can begin to develop effective preventive interventions to prevent the behavior and its negative effects. This investigation illustrates one way to use qualitative methodology to produce in-depth information on the motivations of cyberbullying in a local context (e.g., culture specificity) that may be a useful model for future research on this topic.22

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the youth who shared their stories about their lives in cyberspace.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: By the WestJEM article submission agreement, all authors are required to disclose all affiliations, funding sources, and financial or management relationships that could be perceived as potential sources of bias. Funding for this work was provided through the Center for School Safety, School Climate, and Classroom Management and the Educational Research Bureau in the College of Education at Georgia State University.

Reprints available through open access at http://escholarship.org/uc/uciem_westjem

REFERENCES

- 1.Hinduja S, Patchin JW. Offline consequences of online victimization: School violence and delinquency. J of School Viol. 2007;6(3):89–112. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Diamanduros T, Downs E, Jenkins SJ. The role of school psychologists in the assessment, prevention, and intervention of cyberbullying. Psych in the Schools. 2008;45(8):693–704. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dehue F, Bolman C, Völlink T. Cyberbullying: Youngsters’ experiences and parental perception. CyberPsych & Behav. 2008;11(2):217–23. doi: 10.1089/cpb.2007.0008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vandebosch H, Van Cleemput K. Defining cyberbullying: A qualitative research into the perceptions of youngsters. CyberPsych & Behav. 2008;11(4):499–503. doi: 10.1089/cpb.2007.0042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Katzer C, Fetchenhauer D, Belschak F. Cyberbullying: Who are the victims?: A comparison of victimization in internet chatrooms and victimization in school. J of Med Psych: Theories, Methods, and Applications. 2009;21(1):25–36. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mason KL. Cyberbullying: A preliminary assessment for school personnel. Psych in the Schools. 2008;45(4):323–48. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aricak T, Siyahhan S, Uzunhasanoglu A, et al. Cyberbullying among Turkish adolescents. CyberPsych & Behav. 2008;11(3):253–261. doi: 10.1089/cpb.2007.0016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kowalski RM. Cyber Bullying: Bullying in the Digital Age. Malden, MA: Blackwell; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li Q. New bottle but old wine: A research of cyberbullying in schools. Comput in Hum Behav. 2007;23:1777–91. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Raskauskas J, Stoltz AD. Involvement in traditional and electronic bullying among adolescents. Develo Psych. 2007;43:564–75. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.43.3.564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Slonje R, Smith PK. Cyberbullying: Another main type of bullying? Scandanavian J of Psych. 2008;49:147–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9450.2007.00611.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Smith PK, Mahdavi J, Carvalho M, et al. Cyberbullying: Its nature and impact in secondary school pupils. J Child Psychol Psych. 2008;49(4):376–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2007.01846.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Williams KR, Guerra NG. Prevalence and predictors of Internet bullying. J Adolesc Heal. 2007;41(6):S14–S21. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2007.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shariff S. Cyber-Bullying: Issues and Solutions for the School, the Classroom and the Home. London: Routledge; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ramirez A, Eastin MS, Chakroff J, et al. Towards a communication-based approach to cyber-bullying. In: Kelsey S, St. Amant K, editors. Handbook of Research on Computer Mediated Communications. 1–2. Hershey, PA: Information Science Reference/IGI Global; 2008. pp. 339–52. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ybarra ML, Mitchell KJ. Youth engaging in online harassment: Associations with caregiver-child relationships, Internet use, and personal characteristics. J Adolesc. 2004;27(3):319–36. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2004.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lincoln YS, Guba EG. Naturalistic inquiry. Thousands Oaks, CA: Sage; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schensul JJ, LeCompte MD, Nastasi BK, et al. Ethnographers’ toolkit, Book 3: Enhanced ethnographic methods. Walnut Creek, CA: AltaMira Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 19.LeCompte MD. Ethnographers’ toolkit, Book 3: Analyzing and interpreting ethnographic data. Walnut Creek, CA: AltaMira Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Strauss A, Corbin J. Basics of qualitative research: Grounded theory procedures and techniques. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications, Inc; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Creswell JW. Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five traditions. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nastasi BK. Advances in qualitative research. In: Gutkin TB, Reynolds CR, editors. The Handbook of School Psychology. 4th ed. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 23.LeCompte MD, Schensul JJ. Ethnographers’ toolkits, Book 5: Analyzing and interpreting ethnographic data. Walnut Creek, CA: AltaMira Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]