Abstract

Background

Education about advance directives typically is incorporated into medical school curricula and is not commonly offered in residency. Residents' experiences with advance directives are generally random, nonstandardized, and difficult to assess. In 2008, an advance directive curriculum was developed by the Scott & White/Texas A&M University System Health Science Center College of Medicine (S&W/Texas A&M) internal medicine residency program and the hospital's legal department. A pilot study examining residents' attitudes and experiences regarding advance directives was carried out at 2 medical schools.

Methods

In 2009, 59 internal medicine and family medicine residents (postgraduate year 2–3 [PGY-2, 3]) completed questionnaires at S&W/Texas A&M (n = 32) and The University of Texas Medical School at Houston (n = 27) during a validation study of knowledge about advance directives. The questionnaire contained Likert-response items assessing attitudes and practices surrounding advance directives. Our analysis included descriptive statistics and analysis of variance (ANOVA) to compare responses across categories.

Results

While 53% of residents agreed/strongly agreed they had “sufficient knowledge of advance directives, given my years of training,” 47% disagreed/strongly disagreed with that statement. Most (93%) agreed/strongly agreed that “didactic sessions on advance directives should be offered by my hospital, residency program, or medical school.” A test of responses across residency years with ANOVA showed a significant difference between ratings by PGY-2 and PGY-3 residents on 3 items: “Advance directives should only be discussed with patients over 60,” “I have sufficient knowledge of advance directives, given my years of training,” and “I believe my experience with advance directives is adequate for the situations I routinely encounter.”

Conclusion

Our study highlighted the continuing need for advance directive resident curricula. Medical school curricula alone do not appear to be sufficient for residents' needs in this area.

Introduction

Education on advance directives is often incorporated into medical school curricula along with education on ethics and humanism, but formal curricula on advance directives are not commonly offered by residency programs. Residents' experiences with advance directives generally are random, nonstandardized, and difficult to assess. In 2008, an innovative advance directive curriculum was developed at Scott & White/Texas A&M University System Health Science Center College of Medicine (S&W/Texas A&M) through a unique collaboration between the internal medicine residency program and the hospital's legal department. An advance directive knowledge assessment tool was developed and is currently being validated at 2 medical schools. The purpose of this paper is 2-fold: (1) to describe the results of a programmatic needs assessment targeting learner attitudes and beliefs surrounding advance directive education and (2) to describe a new, competency-based curriculum in advance directive education for residents.

Background

Americans are living longer with increasing disability from chronic diseases.1 Medical advances have improved longevity in the United States, and life expectancy is now 77.7 years.2 In addition, significantly more trauma patients now survive previously fatal injuries owing to advances in medical technology and trauma care. Discussions over aggressive medical treatment are commonplace in health care settings, yet conversations regarding end-of-life care are relatively uncommon. Advance directives have been promoted by ethicists and lawyers, patient advocacy groups, and hospitals to enhance patient autonomy and ensure patients' wishes are followed at the end of life or in situations where they may not be competent to voice their personal decisions.3

Advance directive is a general term for a set of documents outlining a patient's wishes regarding medical decision-making surrounding the withholding or withdrawing of life-sustaining treatment and any institutional policies regarding the same. One such advance directive, the Durable Power of Attorney for Health Care4 or Medical Power of Attorney, allows patients to designate individuals to make health care treatment decisions for them when they are incapacitated. Advance directives come into play only when a patient's illness/condition is deemed terminal or irreversible, and the patient is not competent to make decisions for himself or herself.

A History of Advance Directives

In 1976, California passed The Natural Death Act, the first law of its kind in the United States.1,4 This was followed by the Texas Natural Death Act in 1977, which included language on living wills.5 In 1990, in the wake of the Quinlan and Cruzan Supreme Court cases, the US Congress passed the Patient Self-Determination Act, which required health care facilities accepting Medicare or Medicaid funds to inform patients in writing of their rights concerning consent to or refusal of medical treatment. This stipulated that patients may execute advance directives in order to protect their rights in the event of incapacity.1,4,6 According to Fine,5 by 1995, Texas had a number of laws affecting end-of-life care. In 1999, the Texas Advance Directives Act, which combined several of these laws into 1 statute, was passed.5 This law provides a number of provisions for patients to make their wishes known regarding end-of-life care, including the Directive to Physicians and Family or Surrogates, Medical Power of Attorney, and the Out-of-Hospital Do-Not-Resuscitate (DNR) form.7 The law stipulates that all hospitals, skilled nursing facilities, home and community support services or specialty care facilities make the forms available to patients.

Advance Directive Education

The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) has not explicitly called for formal education on advance directives, but the professionalism competency stipulates that residents are expected to “demonstrate respect for patient privacy and autonomy.”8 The Alliance for Academic Internal Medicine stresses that internal medicine residents should be competent in skills related to advance directives and end-of-life care.9 Despite the mandate for competence in this area, Aylor et al6 found that 34% of 738 residents participating in a national survey indicated that they had not received any training on the efficacy or legality of advance directives, and 42% reported that they were not knowledgeable about local, state, and federal guidelines concerning these documents.

Only a handful of articles in the literature discuss educational interventions to enhance the advance directive knowledge of physicians. According to the Toller and Budge,10 doctors are often confused about the legal status of advance directives, and when these documents come into play. Aylor and colleagues6 noted that physicians' “limited understanding” (p. 5) of the legal status of advance directives has affected their usefulness in medical decision making. A number of authors have called for enhanced advance directive education, including increased experiential learning.10–13

In a study examining strategies to promote the use of advance directives in an internal medicine residency program, Sulmasy et al14 found that barriers to discussions of advance directives include lack of resident time and lack of continuity. Interventions in this study included lectures, videotapes of model advance directive discussions, and residents reviewing their own discussions with patients about advance directives. Alderman et al15 examined internal medicine residents' knowledge, skills, attitudes, and comfort with advance directives and reported that advance directive knowledge increased after an educational intervention that comprised a 90-minute didactic session and a video presentation of a model advance directive discussion.

The internal medicine residency programs at S&W/Texas A&M and The University of Texas Medical School at Houston (UTMSH) have not offered formal, structured advance directive education to residents. At UTMSH, the residents are provided a monthly didactic series on ethics and professionalism, but advance directives are only presented in general terms without formal intervention or feedback. Residents at both institutions typically learn about advance directives by observing senior colleagues at the bedsides—a common model within apprenticeship models of medical education.13 This article presents data from a pilot study, which is only the first step in a larger program of research addressing advance directive education.

Methods

Research Design

A prospective study aimed at examining residents' attitudes and experience regarding advance directives was undertaken as part of an ongoing advance directive knowledge assessment validation study at 2 Texas medical schools.

Participants

In 2009, 59 internal medicine and family medicine residents (postgraduate year–2 [PGY-2] residents, 29; PGY-3 residents, 28; 2 residents did not indicate year) were recruited from residency programs at S&W/Texas A&M and UTMSH for participation in this pilot study. Internal medicine and family medicine residents at S&W/Texas A&M (n = 32) and internal medicine residents at UTMSH (n = 27) participated in an ongoing advance directive knowledge assessment validation study and completed advance directive attitudes questionnaires during that time period. Age range of participants was 26 to 55 years.

Measurement Instrument

An advance directive attitudes questionnaire was created by an interdisciplinary research team at S&W/Texas A&M. The team comprised faculty from the S&W/Texas A&M Internal Medicine Residency Program Office, the Internal Medicine Medical Education Office, an attorney with the Texas A&M Health Science Center College of Medicine's Humanities Department, and an attorney with the Scott & White Memorial Hospital's Department of Risk Management. The questionnaire, which is being used as a programmatic needs assessment, contains demographic items and 7 Likert-scale questions probing attitudes and practices surrounding advance directives. The questionnaire was developed as part of an ongoing advance directive knowledge assessment validation study. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards at Scott & White Healthcare and The University of Texas Medical School at Houston and granted exemption from further oversight.

Data Analysis

Our analysis used descriptive statistics (SPSS 17.0, Chicago, IL) and calculation of frequencies on the questionnaire data to determine the number and percentage of residents endorsing the Likert-scale options for each item. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to compare questionnaire responses across residency categories. The P value was set at .05.

Results

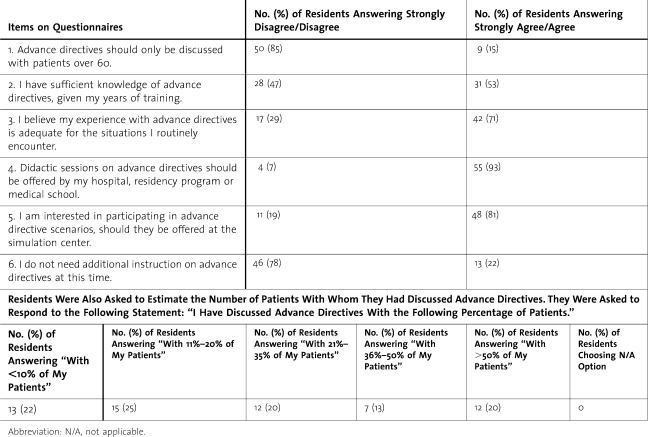

Results of the data analysis are reported in the table. The results for item 2 were split between those endorsing agree/strongly agree and strongly disagree/disagree, with 31 of 59 residents (53%) agreeing or strongly agreeing they had “sufficient knowledge of advance directives, given my years of training,” with 28 residents (47%) disagreeing or strongly disagreeing with the statement. For item 4, 55 residents (93%) agreed/strongly agreed that “didactic sessions on advance directives should be offered by my hospital, residency program or medical school.”

Table.

Results of Advance Directive Attitudes Questionnaire Given to Internal Medicine and Family Medicine Residents (n = 59) at 2 Medical Schools

Responses to the 7 questionnaire items were tested across years of training. Data from 57 participants were analyzed (n = 2, missing data). For this analysis, responses were assigned numerical values, with “strongly disagree” receiving a value of 1 and “strongly agree” receiving a value of 4. ANOVA indicated there were statistically significant differences between the ratings of 3 items.

For item 1, “Advance directives should only be discussed with patients over 60,” there was a statistically significant difference between ratings by PGY-2 residents (n = 29, M = 1.59, SD = .57) and ratings by PGY-3 residents (n = 28, M = 2.04, SD = .92) (F1,56 = 4.95, P < .03). For item 2, “I have sufficient knowledge of advance directives, given my years of training,” we found a statistically significant difference between ratings by PGY-2 residents (M = 2.34, SD = .67) versus PGY-3 residents (M = 2.79, SD = .57) (F1,56 = 7.16, P < .01). For item 3,“I believe my experience with advance directives is adequate for the situations I routinely encounter,” we also found a statistically significant difference between ratings by PGY-2 residents (M = 2.59, SD = .78) and PGY-3 residents (M = 2.96, SD = .51) (F1,56 = 4.67, P < .03).

Discussion

Patient choice does not appear to consistently play a role in medical decision-making at the end of life, and this has been associated with a weak understanding of advance directives by health care professionals6,10 and the reluctance of patients and/or family members to engage in end-of-life conversations.16 Advances in medical care and technology, an aging US population, and pressures from accreditation and academic organizations have increased the need to promote discussions of advance directives with patients.8,9

Our pilot study highlighted the need for the development of formal advance directive residency curricula and showed that residents desire more formal education and experiences covering advance directives, with 78% of respondents indicating they thought they needed additional instruction on advance directives, and 93% reporting they would welcome didactic sessions on advance directives. Third-year residents rated their knowledge of advance directives and their experience with them higher than PGY-2 residents, although both groups indicated they did not think their knowledge and experience gained during training were sufficient.

We are uncertain how to interpret the finding that PGY-2 residents were more likely to disagree or strongly disagree with item 1 (“Advance directives should only be discussed with patients over 60”) than PGY-3 residents. It is possible that the relatively positive ratings for this item may reflect the demographics of the patient population routinely seen by PGY-3 residents, or residents' limited experience in this area, further suggesting the need for enhanced education in advance directives.

Limitations of our pilot study include a relatively small sample from 2 institutions. The pilot study is part of a larger research effort that includes a validation study of an advance directive knowledge assessment tool and a study of the efficacy of hybrid simulation to prepare residents for code scenarios involving advance directive use.

Future Directions

Advance Directive Curriculum Development

In 2008, a formal advance directive curriculum was developed at S&W/Texas A&M, in collaboration between the Department of Risk Management, the Medical Ethics Committee, and legal counsel. The curriculum included didactic sessions and 3 hybrid scenarios using standardized patients and high-fidelity simulators, allowing faculty to observe residents' discussions of DNR orders with standardized patients and assess residents' ability to deal with ethical and legal considerations in end-of-life care.

The hybrid scenarios included an inpatient situation with an out-of-hospital DNR order; a patient with family members who revoke a DNR order; and a patient with family members who want to withdraw care, when the patient has a reversible condition. These scenarios allow residents to practice skills related to obtaining an advanced directive, following a previous order of an advanced directive, and work through family differences of opinion and conflicts. An important goal is to enhance knowledge of state law regarding advance directives. Exercises emphasize understanding and use of advance directives within the ACGME competency framework, with a focus on interpersonal and communication skills, professionalism, and systems-based practice. The scenario sessions are followed by a debriefing, which includes discussions of ethical and legal issues surrounding advance directives.

To date, the new advance directive hybrid curriculum has been piloted at S&W/Texas A&M. After participation in 2 scenarios, residents were asked if they felt the exercises were helpful in preparing them for future situations where advance directives come into play. Resident comments included the following:

“…[In] the first one [scenario], I allowed myself to be distracted and not actually take care of the patient. Yes, the patient needed to be coded, yes there was something we could have done. With the second one [scenario], I felt less distracted. I think I could have better managed the family member. It was good.”

“I was concentrating on the discussion with the family this time more than I was the code.… I was trying to do two things at once, so it was harder.”

“I think simulation is just an approximation of real life. In real life, when we're in there doing codes, you've got team members. And at least one team member has to take care of the family member, and the others have to take care of the patient. This [the simulation center] is the place you can practice looking up medicines, practice your seal, practice compressions, and then it's not as scary when you do it in real life.”

“It's better when we screw it up over here [in the simulation center]. Honestly.”

To our knowledge, this is the first report of the development and implementation of a hybrid high-fidelity advance directive curriculum for residents. Future efforts include continued collaborations with the Texas A&M College of Medicine's Department of Humanities and UTMSH, as well as continuing implementation of the advance directive curriculum at S&W/Texas A&M during the 2010–2011 academic year. Research on the efficacy of the advance directive curriculum will be undertaken during 2010–2011. Our validation study of the advance directive knowledge assessment tool is ongoing at S&W/Texas A&M and UTMSH.

Footnotes

Colleen Y. Colbert, PhD, is Senior Medical Educator and Assistant Professor, Internal Medicine Department, Scott & White/Texas A&M HSC College of Medicine (COM); Curtis Mirkes, DO, is Assistant Professor, Internal Medicine Department, and Associate Program Director, Scott & White/Texas A&M HSC COM Internal Medicine Residency Program; Paul E. Ogden, MD, is Professor, Associate Dean for Academic Affairs and Regional Chair of Internal Medicine, Texas A&M HSC College of Medicine; Mary Elizabeth Herring, JD, is an Attorney and Associate Professor in the Department of Humanities in Medicine, Texas A&M HSC College of Medicine; Christian Cable, MD, is Assistant Professor, Internal Medicine Department, and Program Director, Hematology/Oncology Fellowship Program, Scott & White/Texas A&M HSC COM; John D. Myers, MD, is Assistant Professor and Interim Vice Chair for Educational Affairs, Internal Medicine Department, and Program Director, Scott & White/Texas A&M HSC COM Internal Medicine Residency Program; Allison R. Ownby, PhD, is Director, Office of Educational Programs, and Assistant Professor, Department of Pediatrics, The University of Texas Medical School at Houston; Eugene Boisaubin, MD, is Professor, Internal Medicine Department, Associate Program Director, Internal Medicine Residency Training Program, Director, Ethics and Advocacy Core, NIH Center for Clinical and Translational Sciences, and Distinguished Teaching Professor of Medicine, The University of Texas Medical School at Houston; Ida Murguia, JD, is Assistant General Counsel, Scott & White Healthcare, Temple, TX; Mark A. Farnie, MD, is Associate Professor, Departments of Internal Medicine and Pediatrics, and Program Director for the Internal Medicine Residency Training Program and Internal Medicine/Pediatric Residency Training Program at The University of Texas Medical School at Houston; Mark Sadoski, PhD, is Distinguished Research Fellow, College of Education and Human Development, and holds joint appointments in the Texas A&M University Department of Teaching, Learning and Culture, the Department of Educational Psychology, and the College of Medicine's Office of Medical Education.

We would like to acknowledge the assistance of Mr Glen Cryer, BA, Manager of the Scott & White Publications Office, and June Lubowinski, MLS, MA, Public Services Librarian at Scott & White Hospital, for their assistance with this article.

References

- 1.Wilkinson A., Wenger N., Shugarman L. R. Rand Corporation. Literature review on advance directives. US Department of Health and Human Services; prepared for the Office of Disability, Aging and Long-Term Care Policy, Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation. Available at: http://aspe.hhs.gov/daltcp/reports/2007/advdirlr.pdf. Published June 2007. Accessed April 19, 2010.

- 2.Centers for Disease Control. FastStats: life expectancy (data are for the U.S.) Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/lifexpec.htm. Accessed April 19, 2010.

- 3.Schicktanz S. Interpreting advance directives: ethical considerations of the interplay between personal and cultural identify. Health Care Anal. 2009;17(2):158–171. doi: 10.1007/s10728-009-0118-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Markus K. The law of advance directives: legal documents can ease end-of-life decisions. Available at: http://www.scu.edu/ethics/publications/iie/v8n1/advancedirectives.html. Accessed April 19, 2010.

- 5.Fine R. L. The Texas Advance Directives Act of 1999: politics and reality. HEC Forum. 2001;13(1):59–81. doi: 10.1023/a:1011249928196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aylor A. L., Koen S., MacLaughlin E. J., Zoller D. Compliance with and understanding advance directives in trainee doctors. J Miss State Med Assoc. 2009;50(1):3–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.State of Texas. The Advance Directives Act. Available at: http://www.statutes.legis.state.tx.us/DOCS/HS/htm/HS.166.htm. Accessed April 28, 2010.

- 8.Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. ACGME Outcome Project—Common Program Requirements: general competencies. Available at: http://www.acgme.org/outcome/comp/compCPRL.asp. Accessed May 25, 2010.

- 9.Alliance for Academic Internal Medicine (AAIM) The “core” of internal medicine: core competencies and core content. Available at: http://www.im.org/PolicyAndAdvocacy/PolicyIssues/Education/Documents/FINALCoreCompetenciesandCoreContent.pdf. Published November 25, 2007. Accessed April 19, 2010.

- 10.Toller C. A., Budge M. M. Compliance with and understanding of advance directives among trainee doctors in the United Kingdom. J Palliat Care. 2006;22(3):141–146. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Buss M. K., Alexander G. C., Switzer G. E., Arnold R. M. Assessing competence of residents to discuss end-of-life issues. J Palliat Med. 2005;8(2):363–371. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2005.8.363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Deep K. S., Green S. F., Griffith C. H., Wilson J. F. Medical residents' perspectives on discussions of advanced directives: can prior experience affect how they approach patients? J Palliat Med. 2007;10(3):712–720. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2006.0220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Furman C. D., Head B., Lazor B., Casper B., Ritchie C. S. Evaluation of an educational intervention to encourage advance directive discussions between medicine residents and patients. J Palliat Med. 2006;9(4):964–967. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2006.9.964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sulmasy D. P., Song K. Y., Marx E. S., Mitchell J. M. Strategies to promote the use of advance directives in a residency outpatient practice. J Gen Intern Med. 1996;11(11):657–663. doi: 10.1007/BF02600156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Alderman J. S., Nair B., Fox M. D. Residency training in advance care planning: can it be done in the outpatient clinic? Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2008;25(3):190–194. doi: 10.1177/1049909108315301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Emanuel L. L. Advance directives. Ann Rev Med. 2008;59(1):187–198. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.58.072905.062804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]