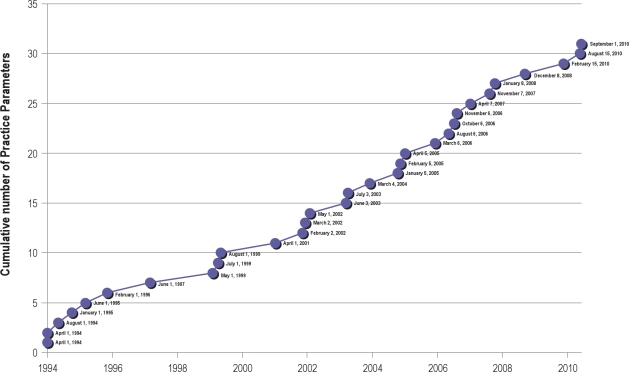

AS THE CURRENT DEBATE OVER HEALTH CARE REFORM INTENSIFIES AND THE MANDATE TO CONTROL EVER-ESCALATING HEALTH CARE COSTS MOVES TO the top of the political agenda, evidence based medicine is becoming increasingly recognized as a critical instrument to help manage these issues. Evidence based medicine may be globally defined as the judicious use of the best current evidence in making decisions about the care of the individual patient. While the term “evidence based medicine” (EBM) first appeared in the medical literature in 1990,1 traces of EBM origins date back to ancient Greek and Chinese medicine. The Standards of Practice Committee was founded in the early 1990s and produced some of the first evidence based practice guidelines in medical practice (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Cumulative practice parameter products of the Standards of Practice Committee

In the EBM world, “evidence” is generally considered to consist of published opinions and the results of various trials or studies regarding health care. Deciding what is “the best current evidence” necessitates development of a system that can be used to judge which published conclusions to trust more and which less. The last two decades have seen the emergence of a multitude of evidence grading systems with varying successes. The Standards of Practice Committee (SPC) of the American Academy Sleep of Medicine (AASM) has developed 31 practice parameter/best practices papers based on the systematic review of existing literature in an effort to provide diagnostic and treatment strategies for typical practitioners. The Oxford Levels of Evidence has been the primary grading system used by the SPC to grade evidence and assign recommendations. A significant advantage of this system is that it lends itself to many types of studies covering various aspects of the medical management of patients, including diagnosis as well as therapeutic interventions. However, inherent limitations in this system (as well as others) include the lack of a framework to separately evaluate the rigor of available evidence and the strength of recommendations. There has been an implicit implication that strong evidence leads to strong recommendations. This approach ignores the many other factors that are considered in developing recommendations, such as values, effect size, risks, costs, and alternative options. Such limitations may result in misinterpretation of the assigned recommendations by practitioners, insurance companies, and policy makers. In an effort to incorporate the strengths of preexisting grading systems while addressing their inadequacies, guideline developers, methodologists, and clinicians collaborated to form the Grades of Recommendation, Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) Working Group.2 Since then, a number of international and national professional organizations have adopted the GRADE system either in its original format or with some modifications for guideline development.

This document intends to explicate the advantages offered by the GRADE system over our previously used evidence assessment system and elucidate the modified GRADE system that is being adopted for implementation by the SPC and Task Forces commissioned by the AASM leadership.

THE IMPETUS FOR CHANGE

Early evaluation systems relied heavily on study design to determine the degree of confidence to invest in conclusions. Typically, observational studies will provide weaker confidence than randomized control trials because there are often more opportunities for the entry of bias. However when reviewing a study, other elements are likely to be of consequence and should be represented. In evaluating the evidence, the GRADE system recognizes not only study design, but also study quality, the directness with which the data addresses the clinically relevant question, the sample size, and the direction in which biases might have affected the conclusions. When looking at the totality of the evidence, randomized control trials start off at a “high” grade, observational studies (cohort studies, case control studies, interrupted time series analysis, and controlled before and after studies) are considered a “low” grade, and other study designs (unsystematic observational studies such as case reports/series) are initially designated as a “very low” grade. Studies can be upgraded or downgraded after evaluating serious limitations, biases, and uncertainty about directness. Furthermore, a body of evidence may be judged by taking into account the consistency of the conclusions from multiple studies, the effect size, and the influence reporting biases may have produced. The final overall quality of evidence across studies for a particular outcome are expressed as: (1) High—indicating that further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect; (2) Moderate—indicating that further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate; (3) Low—further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate; and (4) Very low—any estimate of effect is very uncertain.3

In an evolving and unique field such as sleep medicine where randomized control trials are not always feasible, our prior evidence grading system might underestimate the utility and impact of observational studies while overvaluing a low-quality RCT. The GRADE system offers simplicity, clarity, and transparency in grading the evidence and allows merit to be placed on well conducted observational studies—many of which have provided powerful epidemiological data to the mounting body of sleep literature.4

Box 1. Criteria for assigning grade of evidence11.

- Type of evidence

- Randomized trial High

- Observational study Low

- Any other evidence Very Low

- Decrease grade if:

- Serious (−1) or very serious (−2) limitation to study quality

- Important inconsistency (−1)

- Some (−1) or major (−2) uncertainty about directness

- Imprecise or sparse data (−1)

- High probability of reporting bias (−1)

- Increase grade if:

- Strong evidence of association – significant relative risk >2 (< 0.5) based on consistent evidence from two or more observational studies, with no plausible confounders (+1)

- Very strong evidence of association – significant relative risk of > 5 (< 0.2) based on direct evidence with no major threats to validity (+2)

- Evidence of a dose response gradient (+1)

- All plausible confounders would have reduced the effect (+1)

While there is a hierarchy of evidence such that higher quality studies that offer greater protection against bias and random error can be used more confidently, evidence alone is not sufficient to make clinical decisions, replace clinician experience, or reflect patient preference. The GRADE system recognizes and incorporates these other key factors in the process for developing recommendations. In the framework of GRADE, recommendations are made based on the quality of evidence as outlined above and combined with an examination of the following questions: first—does the intervention do more good than harm, and second—are the incremental health benefits worth the cost. In addressing the former, there is recognition that a value determination (either implicitly or explicitly) is placed on a particular outcome. Undeniably, different people will have different values, and it is often difficult to determine how much weight to assign to various outcomes. However the GRADE literature underscores that understanding the values of those affected will place practitioners on a stronger ground when making choices on behalf of or with those affected. The GRADE working group suggests the use of the following categorization to assess the issue of benefit versus harm: Net benefits = the intervention clearly does more good than harm; Trade-offs = there are important trade-offs between the benefits and harms; Uncertain trade-offs = it is not clear whether the intervention does more good than harm; and No net benefits = the intervention clearly does not do more good than harm. The GRADE method acknowledges that the balance between benefit and harm can vary with varying population or medical settings. The GRADE workgroup advocates that recommendations be made patient specific whenever possible.

Additionally, in order to improve the value of care provided ((outcomes + service + safety)/costs across time), the costs of delivering and not delivering diagnoses and therapies should be considered. The GRADE system offers the opportunity to integrate financial aspects into the decision-making process while not having them supersede other essential elements such as the quality of evidence or benefit/harm assessment. The GRADE working group suggests estimating costs of the intervention as well as costs for alternative therapies whenever possible. If feasible, these outcomes should be graded in a similar manner to other outcomes and considered explicitly alongside of benefit/harm determinations.

Compared to the current system of evidence evaluation being used by the SPC, the GRADE system is able to separate the quality of the evidence from the level of recommendation, concurrently incorporate the benefit/harm estimation into the evaluation, and consequently provide a more germane recommendation that reflects a more encompassing appraisal. An interesting example of how the GRADE system would alter the level of recommendation that was assigned employing our current system is noted for the use of pemoline in narcolepsy. The most recent practice parameter5 assigns an option level of recommendation as “Pemoline has rare but potentially lethal liver toxicity, is no longer available in the United States, and is no longer recommended for treatment of narcolepsy.” This level of recommendation choice was influenced by the relative scarcity of “high quality” evidence (i.e., no randomized, double-blind trials). With the GRADE system a recommendation assignment of standard would be given as (1) the harms may outweigh the benefit, (2) there are alternative safer options, and (3) because we place a very high value on patient safety. The GRADE system enables users to apply equal merit to the values/tradeoffs assessment and the evidence quality review when determining the level of recommendation. Most importantly, the process is transparent. In this example, although the quality of evidence essentially made pemoline an option level recommendation in terms of the effectiveness of the drug in narcolepsy, the superseding issue is that the medication is dangerous, and the committee would advise against its use. Our message regarding pemoline usage would probably have had greater clarity if we had used the GRADE system at that time.

Box 2. Final assessments of evidence of grade.

High (Level 4): Further research is very unlikely to change confidence in the estimate of effect

Moderate (Level 3): Further research is likely to have an important impact on the confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate

Low (Level 2): Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate

Very low (Level 1): Any estimate of effect is very uncertain

Another example may serve to illustrate these issues. In the recent “Practice Parameters for the Use of Autotitrating Continuous Positive Airway Pressure Devices for Titrating Pressures and Treating Adult Patients with Obstructive Sleep Apnea Syndrome: An Update for 2007,”6 the following parameter, probably the most pertinent of parameters in that paper, was issued at the “Option” level:

3.5. Certain APAP devices may be initiated and used in the self-adjusting mode for unattended treatment of patients with moderate to severe OSA without significant comorbidities (CHF, COPD, central sleep apnea syndromes, or hypoventilation syndromes). (Option)

The “Option” level was chosen because there of the heterogeneous nature of the available literature for review as regards patient types, devices, and the nature of outcomes studied. There was a lack of directness regarding the recommendation being addressed. In the GRADE formulation, the evidence would have been considered moderate in quality; the use of APAP would probably have been assessed as having uncertain trade-offs (comparing APAP with CPAP) but probable important net benefit compared with no CPAP or in selected patient types. The main risks of using APAP would be leaving patients incompletely treated, and this may be mitigated by selecting the right candidates (those without “congestive heart failure, significant lung disease such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, patients expected to have nocturnal arterial oxyhemoglobin desaturation due to conditions other than OSA (e.g., obesity hypoventilation syndrome), patients who do not snore (either naturally or as a result of palate surgery), and patients who have central sleep apnea syndromes”) and close and conscientious follow-up to ensure complete treatment. Thus, it is likely that using the GRADE method; the parameter would have received a “Guideline” level recommendation (vide infra).

HOW RECOMMENDATIONS WILL CHANGE IN FUTURE PRACTICE PARAMETERS OF THE AASM

The SPC has historically offered 3 levels of recommendations based primarily on quality of evidence graded per the Oxford Levels of Grading:

Prior AASM Levels of Recommendation and their Definitions

Standard: This is a generally accepted patient-care strategy that reflects a high degree of clinical certainty. The term standard generally implies the use of Level 1 evidence, which directly addresses the clinical issue, or overwhelming Level 2 evidence.

Guideline: This is a patient-care strategy that reflects a moderate degree of clinical certainty. The term guideline implies the use of Level 2 evidence or a consensus of Level 3 evidence.

Option: This is a patient-care strategy that reflects uncertain clinical use. The term option implies either inconclusive or conflicting evidence or conflicting expert opinion.

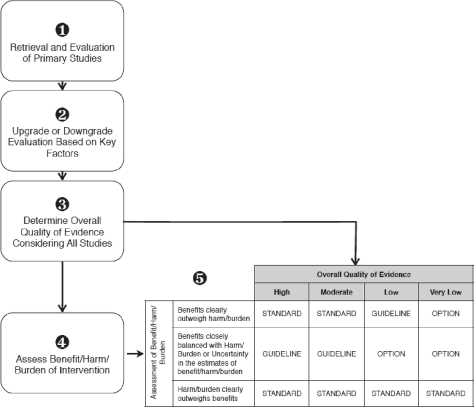

A strict implementation of the GRADE system classifies recommendations as being either strong (using phrases such as “we recommend,” “clinicians should”) or weak (“we suggest,” “clinicians might”), according to the balance of the benefits and downsides (harms, burden, and costs) after considering the quality of evidence. Adopting such GRADE recommendation wordings without modification may have far-reaching implications in view of current AASM accreditation recommendations for sleep centers and laboratories. Instead, we feel that adapting the GRADE system while maintaining the current SPC nosology for levels of recommendation could result in the most favorable combination. Thus, the new SPC recommendations will look the same, but will be informed by an evaluation using the GRADE system as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

AASM adaptation of GRADE system for evaluation of evidence. Literature searches will reveal published articles that pertain to the clinical question being asked (Step 1). The quality of these studies will be assessed according to the GRADE recommendations (Step 2, see Box 1). The assessed articles will be examined as a whole to determine the overall quality of evidence pertaining to the clinical question (Step 3, see Box 2). The overall quality of evidence is then combined with the assessment of the balance of benefit/harm/burdens of the intervention using the matrix to determine a final strength that will be assigned to the recommendation in the standards of practice papers (Step 5).

As new Standards of Practice documents are developed, not only will the recommendations be followed by an indication of the strength of the recommendation as has always occurred (Standard, Guideline, Option), but where possible, values and tradeoffs will be explicitly outlined and taken into consideration along with the strength of the evidence in forming the recommendation. Meta-analytic techniques will be employed when possible. As comparative costs for tests and treatments become more transparent, these may also begin to influence the strength of recommendations.

UPCOMING PRACTICE PARAMETER PAPERS

It takes time to develop practice parameter papers, and some have been years in the making. Accordingly, although the transition to the GRADE system has commenced, some of the practice parameter papers that will be released over the coming 12 months may not be using the GRADE system. The update of Surgical Modifications of the Upper Airway for the Treatment of Obstructive Sleep Apnea and a parameter under development regarding treatment of Central Sleep Apnea will use GRADE, while forthcoming practice parameters regarding pediatric indications for polysomnography will not be using GRADE. While the AASM is committed to providing as much clarity and transparency as possible during this process, patience will be required from readers and members to minimize misinterpretation during the transition.

FINAL THOUGHTS

Though the SPC Practice Parameter papers have a proud history and have served to help form our field and benefit our patients, it is time to modify our grading and recommendation system. The new system promotes explicit consideration to worthwhile factors such as benefit/harm assessment and costs, more accurately assesses quality of evidence, and still provides transparency, simplicity, and clarity. Adapting the GRADE system to our uses permits continuity in our current accreditation standard. The GRADE system represents a promising development in EBM, however, as with any grading system, the GRADE system also has limitations. Differences in opinion between guideline developers and users regarding balance of benefits and downsides in recommendations could pose a significant problem. Furthermore, evaluation of costs is often imprecise. Additionally, the application of the GRADE system for assessment of diagnostic tests remains under development and needs to be investigated. Another challenge for the sleep medicine community will be formulation of metrics by which we may measure the value we are actually delivering to our patients and communities. Presumably, in so far as Practice Parameters represent what would be good for a majority of patients, our adherence to them might serve as one measure. As evidence based medicine evolves, these controversial issues need to be incorporated into the shifting paradigm.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

Dr. Aurora has indicated no financial conflicts of interest. Dr. Morgenthaler has received research support from ResMed.

REFERENCES

- 1.Eddy, DM “Practice policies: where do they come from?”. JAMA. 1990;263:1265. doi: 10.1001/jama.263.9.1265. 1269, 1272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. http://www.gradeworkinggroup.com.

- 3.Atkins D, Best P, Brist PA, et al. Grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ. 2004;328:1490. doi: 10.1136/bmj.328.7454.1490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bixler EO. Epidemiology of sleep disorders: clinical implications. Sleep Med Clin. 2009;4:1–98. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Morgenthaler TI, Kapur VK, Brown TM, et al. Practice parameters for the treatment of narcolepsy and other hypersomnias of central origin. An American Academy of Sleep Medicine Report. Sleep. 2007;30:1705–11. doi: 10.1093/sleep/30.12.1705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Morgenthaler TI, Aurora RN, Brown T, et al. Practice parameters for the use of autotitrating continuous positive airway pressure devices for titrating pressures and treating adult patients with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome: an update for 2007. An American Academy of Sleep Medicine Report. Sleep. 2008;31:141–7. doi: 10.1093/sleep/31.1.141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]