Introduction

Cardiovascular disease is a leading cause of death worldwide. Nearly 2400 Americans die of cardiac causes each day, one death every 37 seconds.1 Thus the heart still reigns supreme -”foundation of their (animals) life, the sovereign of everything within them, the sun of their microcosm, that upon which all growth depends, from which all power proceeds”-William Harvey, 1628.

Effective myocardial function is primarily dependent on oxidative energy production. In humans, at a heart rate of 60–70 beats/min the oxygen consumption normalized per gram of myocardium is 20-fold higher than that of skeletal muscle at rest. As an adaptation to this high oxygen demand, the heart maintains a very high level of oxygen extraction of 70–80% compared with 30–40% in skeletal muscle.2 This is facilitated by the capillary density of 3000–4000/mm2, compared to 500–2000 capillaries/mm2 in skeletal muscle, and a tight regulation of the coronary blood flow.3 In the case of exercise-induced hypertrophy, the heart preserves the oxygen supply/demand matching the proportional increases in cardiac myocyte size and the extent of coronary microvasculature.3, 4 Different forms of hemodynamic stress (e.g. hypertension, aortic stenosis, coarctation of the aorta, mitral regurgitation and myocardial infarction, among others) increase intraventricular pressure or volume and lead to an hypertrophic response.5 A prolonged increase in the wall stress may result in progressive ventricular dilation and myocardial decompensation due to ongoing myocyte death and fibrosis, and, ultimately, to heart failure and death.6, 7 This pathological progression demonstrates a mismatch between oxygen supply and demand, as the extent of cardiomyocyte hypertrophy is not matched by a corresponding increase in the arterial blood supply.3

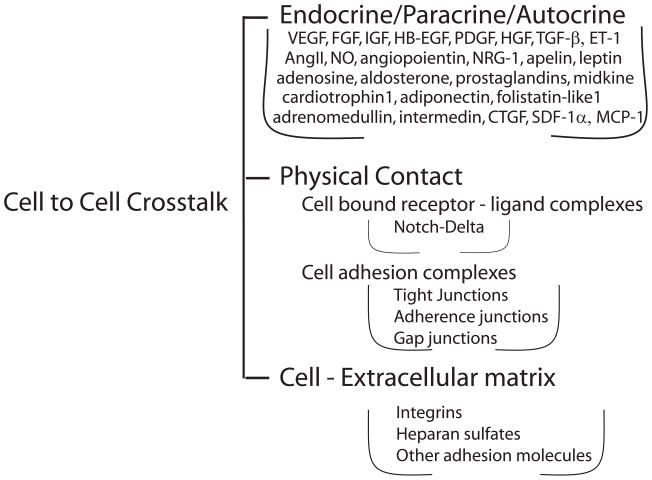

The human heart contains an estimated 2–3 billion cardiac muscle cells, but these account for less than a third of the total cell number in the heart. The balance includes a broad array of additional cell types, including smooth muscle and endothelial cells of the coronary vasculature and the endocardium, fibroblasts and other connective tissue cells, mast cells and immune system-related cells. Recently, pluripotent cardiac “stem cells” have also been identified in the heart. 8 These distinct cell pools are not isolated from one another within the heart, but instead interact physically and via a variety of soluble paracrine, autocrine and endocrine factors (summarized in Figure 1). Thus, to fully understand the biology and pathobiology of the heart the influences of these cellular crosstalks must be considered.

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of cell-cell communication modalities in the heart. Types of cell-cell cross-talk and their mediators. Abbreviations are the same as in the text.

In this review we will discuss new insights into molecular regulation of a myocardial hypertrophic response focusing on contribution of cell-cell crosstalk in the heart to this process.

1. Cardiac Myocytes

The differences among exercise vs. pressure-induced hypertrophy exemplify the profound importance of extrinsic factors as determinants of myocardial morphology and function. These factors can be either physical (myocardial wall tension, myocyte stretch, etc.) or molecular-chemical (growth factors, cytokines, and other circulating or locally produced bioactive molecules). In addition to directly affecting myocytes, the same factors can also affect the non-myocyte cell populations in the heart. Thus, in cardiac responses to a specific physiological or pathophysiological stimulus, intrinsic signaling pathways within the myocytes, as well as crosstalk between myocytes and other cell populations within the heart, play crucial and interdependent roles.

The sine qua non of myocardial hypertrophy is an increase in cardiac myocyte size rather than an increase in cell number.9 This increase in size is generally due to an increase in the number of sarcomere units within each myocyte. The alignment of these additional sarcomeres either in series or in parallel within the cell defines whether thicker, or more elongated myocytes result. Multiple intracellular signaling pathways and molecular effectors are involved in the regulation of cardiomyocyte hypertrophy, including G protein isoforms, calcineurin, insulin-like growth factor (IGF)-I, fibroblast growth factors (FGFs), transforming growth factor (TGF)-β, Ras GTPases, MAPK cascades, histone deacetylases (HDACs) and a repertoire of transcription factors (e.g. NFAT, GATA4, NF-κB, Mef-2, SRF).5 The ultimate result of the action of this panoply of players is the promotion of protein synthesis, assembly of additional sarcomeres, and activation of the fetal cardiac gene program (e.g. ANF, BNF, β-MHC).

The type of hypertrophy that results is likely determined by a complex cross-talk between these various intracellular signaling pathways, with a preponderance of specific signaling events directing specific patterns of cardiac hypertrophy. Recently, for example, physiological hypertrophy was linked with activation of the PI3K/Akt pathway by growth factors, whereas pathological hypertrophy was linked to neurohumoral signaling pathways induced by stress mediators such as angiotensin II (AngII) and endothelin 1(ET1) via G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) and the Gq heterotrimeric G protein. 5, 10

1.1. Cardiomyocyte to Cardiomyocyte Communication – Talking Among Themselves

There are many routes that allow cardiomyocyte-cardiomyocyte communications, including the secretion of autocrine factors, cell-cell propagation of depolarization fronts, and physical association via gap junctions and adhesion complexes. Autocrine communications are carried out by rich panoply of myocyte-secreted factors that include, among others, leptin, FGF and TGFβ family members, midkine, hepatocyte growth factor, endothelin-1, and SDF1α. The end result of secretion of these factors in the heart is then a combination of a cardiomyocyte-cardiomyocyte and cardiomyocyte-non-cardiomyocyte cell interactions.

The complexity of these interactions can be seen in studies of ET-1 signaling. A cardiomyocyte-specific deletion of ET-1 significantly attenuated thyroxin-induced cardiac hypertrophy, suggesting involvement of an autocrine circuit.11 However, cardiomyocyte-specific deletion of the ET-1A receptor had no effect on isoproterenol or Ang II-induce cardiac hypertrophy or dysfunction.12 Therefore, either the upregulation of cardiomyocyte ET-1B receptors or the action of ET-1 on alternative cell types in the heart is responsible for these observations. Nonetheless, given the pronounced role of cardiac myocytes as secretory cells, and the presence of myocytes receptors for these secreted factors, it is likely that many important cardiomyocyte-centered autocrine loops are operative in the heart.

Direct myocyte-myocyte communications via gap junctions are more straightforward in this regard. Gap junctions exist among most mammalian cell types, and allow cell-cell communication via the passage of ions and small solutes between them.13 In the heart, gap junctions and gap junction proteins of the connexin family have been shown to play a crucial role in determining impulse conduction and the heart morphogenesis.14 Global deletion of connexin 43 in mice causes neonatal death from conotruncal malformation and outflow obstruction.15 Both heterozygous as well as homozygous global deletion of connexin 40 in mice result in developmental defects in the heart, including double outlet right ventricle, tetralogy of Fallot, and various endocardial cushion defects.16 The specific importance of connexin 43 in myocardial gap junctions was further established by cardiomyocyte-specific deletion studies that demonstrated postnatal lethality with no survival of homozygous knockout pups beyond postnatal day 16.17 Interestingly, although no morphological abnormalities were noted in these mice during embryonic development, ventricular hypertrophy and outflow track abnormalities were observed after birth.

Gap junction remodeling, a set of molecular and functional changes that occur at the gap junction during myocardial hypertrophy, includes alteration in the expression and phosphorylation of specific connexins18 and lateralization of the gap junction from the intercalated disc.19 This results in altered impulse conduction, but may also include other, yet undefined, effects on cell-cell communication. Thus, not enough is currently known to prove or disprove the involvement of gap junction communications in myocardial hypertrophy.

Cardiomyocyte-cardiomyocyte communication is clearly not the only context in which gap junctions and connexins play an important role in determining cardiac form and function. The developmental abnormalities associated with the loss of specific connexins during heart embryogenesis have been attributed, for example, to the role of gap junctions in the neural crest and neural tube.20, 21 In addition, gap junctions in the proepicardium are purported to play a role in coronary development and patterning.22

Although the role played by gap junctions in cell-cell communication has been best characterized in terms of communication between cells of the same type, gap junctions may also be involved in crosstalk between diverse cell types. They can form, for example, between cardiac myocytes and fibroblasts, and therefore could conceivably play a role in the crosstalk between these two cell types in the intact heart.23, 24 Myoendothelial gap junctions also form between smooth muscle cells and endothelial cells in blood vessel walls.25, 26 These may play a role in vascular physiology and remodeling, and may also be involved in specific pathological processes affecting the vasculature, such as atherosclerosis27, 28 or vascular remodeling responses to altered hemodynamic loads.29

The third type of cardiomyocyte-cardiomyocyte communication, communication via adhesion complexes, also involves cell-cell contact. Unlike gap junctions in which ions and small molecules are exchanged between cells, adhesion complex communications involve intracellular signaling cascades that are triggered by cell-cell or cell-matrix engagement of specific proteins in these complexes. This type of signaling can alter myocardial responses to growth factors thereby modulating cardiac growth and hypertrophy. These interactions are quite complex, and most emphasis currently is on the cell-matrix rather than cell-cell adhesion-based signaling. This subject is further discussed in a subsequent sections dealing with myocyte-matrix interactions and cross-talk.

Adhesion complexes, cell-cell interaction, and cell-matrix interaction often involve shared pathways and molecular machinery. For example, cardiac myocyte-specific deletion of vinculin, a multiligand protein that links the actin cytoskeleton to the cell membrane, leads to dilated cardiomyopathy and sudden death.30 However, it is also involved in connecting matrix adhesion to the intracellular cytoskeleton and in preservation of intercalated disc structure including organization of gap junctions and the distribution of connexin-43.

1.2. Myocytes-endothelium communications - monologues or dialogues?

As secretory cells, cardiac myocytes are the source of multiple paracrine signals that can affect the coronary vasculature. Some of these- ET1, FGF2, urocortin, adenosine and the enzyme heme oxygenase to name a few, regulate the vascular tone coordinating myocardial requirements for oxygen and nutrients with the blood flow. Endothelin 1 is a powerful vasoconstrictor, while adenosine and urocortin are equally powerful vasodilator. FGF2, in addition to its growth factor properties, has the ability to regulate vascular tone in as yet poorly understood manner.31 Finally, heme oxygenase can modify vascular tone via regulation of carbon monoxide levels.

In addition to the dynamic regulation of the vasculature, cardiomyocyte paracrine signaling can affect long term growth and development of coronary arterial, venous and lymphatic trees. Among these the most important are probably vascular endothelial growth factors (VEGFs) but others also playing a role include multiple FGF, PDGF and TGFβ families members, MCP-1, HGF, midkine, angiopoietins, and others, probably including several yet to be identified factors.

Cardiac myocyte-specific deletion of VEGF-A results in variable embryonic lethality and hypovascular thin-walled hearts suggesting a need for adequate coronary vasculature to complete myocardial morphogenesis.32 Those mice that do survive to adulthood have significant cardiac dysfunction and decreased myocardial vessel density. Of particular interest is the fact that although cardiac myocytes represent less than a third of all cells in the heart, cardiomyocyte-specific deletion of the VEGF-A gene results in a decrease in whole-heart VEGF mRNA synthesis to <15% of normal, underscoring the crucial role of cardiomyocytes as sources of this growth factor in the heart.

VEGF production is increased substantially in the ischemic myocardium 33 and the vasculature in ischemic heart exhibits greater sensitivity to VEGF- and other growth factor-induced vasodilation.34

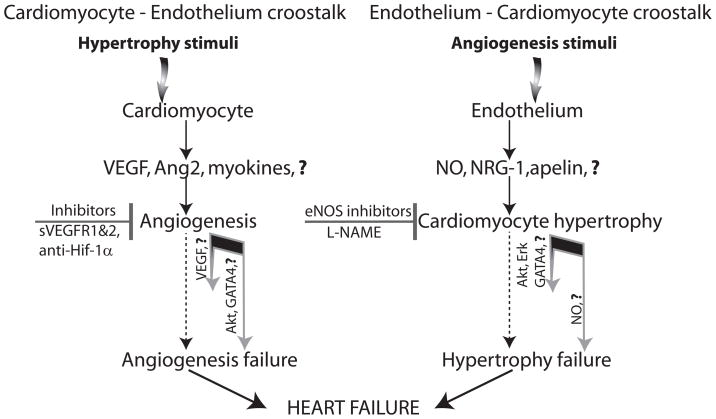

Cardiomyocyte-vascular signaling plays a critical role in the vascular adaptations that occur during myocardial hypertrophy and a failure of the vasculature growth to match the myocyte growth can lead to progressive cardiac dysfunction (Figure 2 left side). During hypertrophic growth, for example, there is a requirement for a commensurate growth of the coronary vasculature to provide adequate oxygen and nutrient delivery to the greater cardiac mass. In addition, a decrease in the vascular cell/myocyte ratio could theoretically also modify the biology of cardiac muscle by reducing the availability of paracrine factors derived from vascular cells that ‘speak to’ cardiac muscle (see below).

Figure 2.

Myocardial hypertrophy as result of cardiomyocyte – endothelium and endothelium – cardiomyocyte crosstalk. Hypertrophic programs can be activated by a direct myocyte stimulation such as pressure or volume overload (left side) or by an expansion of the cardiac vascular mass (right side). Myocyte-driven hypertrophic response includes production of angiogenic growth factors and other myocyte-derived molecules capable of stimulating endothelial expansion (myokines). The angiogenic response is crucial for normal function of the hypertrophic heart and its failure or imbalance in the extent of hypertrophic and angiogenic responses, leads to progressive deterioration of myocardial function and heart failure. On the other hand, increase in the endothelial cell mass in the normal heart can activate myocardial hypertrophy even in the absence of physical stimuli by secretion of nitric oxide, neuregulin (NRG-1) and putative “endokines” (endothelium-derived molecules capable of affecting myocytes). The excess of NO may result in heart failure due to its negative ionotropic properties

Exemplifying the importance of a balance between cardiac growth and vascular growth are studies done in genetically engineered mice in which cardiac hypertrophy was induced by expression of Akt1. During postnatal development, heart growth is significantly modulated by nutritional status and Akt1 signaling in response to growth factors.35 Transgenic overexpression of activated Akt1 in cardiomyocytes resulted in a varied spectrum of phenotypes from cardiac hypertrophy with preserved systolic function, to cardiac dilatation and failure.36 A crucial determinant of whether or not cardiac function is preserved during Akt1-induced hypertrophy is the ability of coronary angiogenesis to keep pace with the increase in cardiac mass. To demonstrate this in a more direct manner, a tetracycline-inducible cardiac myocyte-specific Akt1 transgenic mouse model was used. Short-term (2 weeks) cardiac myocyte-specific induction of Akt1 expression resulted in physiological hypertrophy that was accompanied by commensurate myocardial angiogenesis, driven in part by myocyte-derived VEGF and Angiopoientin-2.37 Akt1 activation for longer periods of time, however, resulted in a disproportional increase in cardiac mass relative to the extent of angiogenesis. This disproportion growth was associated with the development of heart failure, presumably on the basis of an inadequate blood supply to support the hypertrophic ventricle. This exemplifies the importance of coordination between cardiac muscle and the coronary vasculature is in the maintenance of cardiac function, and suggests that angiogenic adaptation is not limitless. 38 Whether this limitation is due to a hypertrophy-associated diminution in myocyte production of specific growth factors and cytokines, or, perhaps, to increased production of molecules with anti-angiogenesis activity, remains unclear.

Myocardial infarction is another clinical setting in which the importance of cardiac myocyte-derived factors influencing the vasculature is in evidence. In fact, there is strong evidence that an important mechanism whereby cell therapy may be beneficial after the infarction is by providing and replenishing growth factors and cytokines that can no longer be made by those cardiac myocytes that have been lost during infarction.

Paracrine and autocrine factors are involved in many aspects of cardiac repair after infarction, including maintenance and reparative growth of the coronary vasculature, remodeling of the extracellular matrix, and possibly maintenance of the viability of those cardiomyocytes that have survived in the infarct and peri-infarct zones. Exemplifying this is follistatin-like 1 (Fstl1), a secreted cardioprotective factor that is highly expressed in the myocardium in response to pressure overload and myocardial infarction.39 Fstl1 acts in autocrine/paracrine manner in a positive feedback loop that promotes myocyte survival through an Akt-mediated signal. Interestingly, Fstl1 expressed in skeletal muscle in the setting of hindlimb ischemia enhanced angiogenesis via an Akt-eNOS pathway.40 Fstl1 is different from other members of follistatin family that act as extracellular binding partners of TGF-β superfamily. Instead, Fstll exerts its cardiovascular protective effects by a receptor-mediated mechanism. A recent in vitro study identifies DIP2A (Disco-interacting protein 2 homolog A), a novel cell-surface receptor, as binding partner for Fstl1 and a mediator of Fstl-induced Akt activation in endothelial cells and cardiomyocytes. 41 These data suggest that Fstl1-DIP2A signaling is involved in cell communication in the heart and may also play an important role in mediating post-infarction coronary angiogenesis.

1.3. Transcriptional Co-Regulation of Cardiomyocyte Growth, Metabolism, and Coronary Vascular Growth

The many cellular “conversations” in the heart must be coordinated to ensure that cell-cell cross talk directs appropriate biological responses, and that various cell types respond in a harmonious fashion to altered environmental factors to which the heart may be exposed. Transcription factors can act as the orchestral conductors in this context, responding to external stimuli and paracrine messages from other cells, and altering the expression of paracrine and autocrine factors produced by the cell in which they reside. One example of such a transcription factor is the hypoxia-inducible factor HIF1α. HIF levels increase in response to hypoxia and ischemia altering the expression of numerous proteins including angiogenic factors, vasomotor tone-determining peptides, proteins that can alter the adhesion characteristics of the endothelium, and those that regulate cardiac myocyte glucose uptake and metabolism, and even those that promote cardiomyocyte survival.42, 43 Genes under transcriptional control by either HIF1 or HIF2α include all the glycolytic enzymes, the Glut1 glucose transporter, VEGF, PDGF-B, HGF, TGFβ1, iNOS, ET1, heme oxygenase, connective tissue growth factor (CTGF), and many others. As such, HIF mediated transcriptional responses coordinate a broad array of vascular and myocyte responses to ischemia.

Another example of a broad transcriptional regulator is GATA4, a transcription factor that modulates cardiomyocyte differentiation and adaptive hypertrophic response in the adult heart. Conditional transgenic expression of GATA4 in cardiomyocytes led to an augmentation of myocardial angiogenesis, increased coronary flow, and perfusion-dependent cardiac contractility.44 Interestingly, GATA4 transgene expression induced angiogenesis even at a low level of expression but only mice with high GATA4 expression showed increases in cardiac mass and myocyte size. This suggests that GATA4-induced angiogenesis was independent of hypertrophic response and that the absolute levels of GATA4 expression determined whether concomitant angiogenesis and hypertrophic cardiac growth occur together, or if angiogenesis occurs alone. The angiogenic effect was mediated in large measure by GATA4 enhanced VEGF-A expression in cardiomyocytes through direct regulation of the VEGF-A promoter, and was reversible with GATA4 cessation indicating that a constant elevation of GATA4 was required.44

2. The Endothelium

The vasomotor control of coronary arteries plays a critical role in maintaining an adequate supply of oxygen to the myocardium in response to physical exercise or hemodynamic stress. The ability of coronary vasculature to dilate and increase the blood flow in the heart results from a plethora of vasodilator and vasoconstrictor factors generated under neurohumoral, endothelial and metabolic influences. Endothelium releases nitric oxide (NO), ET1, Ang-II, prostaglandins, pro-and anticoagulant factors, and various growth factors including FGF, VEGF, and PDGF-BB that can affect numerous parameters of myocardial and vascular function. VEGF, in particular, is a very powerful vasodilator.45

In addition to its well understood role in regulation of vasomotor tone and thrombosis, endothelium plays a role in regulation of the heart size.46 Several studies support the notion that the increase in heart vasculature may not only support cardiomyocyte hypertrophy but may actually induce this process (Figure 2, right panel). For instance, thyroid hormone administration in rats increased vessel density in the heart that was later followed by an induction of a physiological hypertrophy and enhancement of ventricular systolic function.47 This angiogenic response to thyroxine treatment was related, in part, to an early upregulation of FGF2 expression.48

The link between angiogenesis and myocardial hypertrophy was addressed in another study in which an angiogenic peptide (PR39) conditionally expressed in myocardium induced myocardial hypertrophy in the absence of any external stimuli.49 PR39 transgene expression for 3 weeks in the adult mouse heart led to a significant increase in endothelial cell mass and endothelium/myocyte ratio with no changes in the heart size. However, 3 weeks later, there was a significant increase in the heart size that returned the endothelium/myocyte mass ratio to pre-stimulation levels. The heart enlargement was due to an increase in cardiomyocyte size and it was significantly but not completely prevented by concurrent treatment with an eNOS inhibitor L-NAME, thus indicating that an NO-dependent endothelium paracrine signal is responsible for about a half of the observed effect.49

The mechanism by which NO induces cardiomyocyte hypertrophy is not clear and is the subject of active investigations.50 One likely possibility is the role played by NO in the “N-end rule pathway”, a ubiquitin-dependent proteolytic degradation of intracellular proteins in which destabilization of N-terminal residues functions as an essential determinant of signal degradation. Recently, a negative regulator of G proteins type 4 (RGS4) was identified as a substrate for the N-end rule pathway that suggests NO may control Gαq-protein induced hypertrophic signaling by changes in RGS4 levels.51 It would be reasonable to hypothesize that that low NO levels favor RGS4 stabilization by preventing ubiquitin-dependent degradation and thereby blunting Gα-mediated signaling, while high NO levels, as a result, for example, of an increased endothelial cell mass, would favor RGS4 ubiquitination and de-repression of the hypertrophic program.

Transgenic overexpression of VEGF-B in the heart induced an increase in vessel diameters rather than an increase in vessel density that was also accompanied by increases in cardiomyocyte size and heart mass.52 The total myocardial endothelial mass appears to be an important regulator of heart function. A reduction in cardiac VEGF levels by a conditional cardiomyocyte-specific expression of a VEGF trap reduced vessel density leading to hypoperfusion and myocardial hibernation.53 The effect was reversible with the heart fully recovering once the VEGF trap expression was discontinued and the coronary vessel density returned to normal.

It is now well accepted that an increase in the capillary density is important for the development of physiological cardiac hypertrophy whereas a reduction of the capillary bed size underlies transition from a compensated to an uncompensated heart failure. VEGF trap administration during pressure overload accelerates heart failure progression presumably due to inhibition of compensatory growth of the vascular bed or, possibly, due to a reduction in size of the existing vasculature.54 Similarly, reduced VEGF expression during sustained pressure overload as a result of p53 expression-induced inhibitory effect on HIF-1α activity, contributes to functional decompensation of myocardial hypertrophy.55, 56 On the other hand, p53-deficient mice exposed to pressure overload demonstrate a robust compensatory hypertrophic response, improved systolic function and increased capillary density.55

Endothelium is also capable of secreting factors that support cardiomyocyte compensatory response to hemodynamic stress. One of these is neuregulin-1 (NRG-1), a member of the EGF family. The role played by NRG-1 in adult heart accidentally came to light when trastuzumab (Herseptin), an inhibitory antibody against NRG receptor ErbB2 used in the treatment of mammary carcinomas, was discovered to induce cardiomyopathy in treated patients. NRG/ErbB signaling is indispensable during cardiac and neuronal development.57, 58 In the adult heart NRG-1 expression is restricted to the endothelial cells adjacent to cardiomyocytes, whereas its tyrosine kinase receptors ErbB2 and ErbB4 are expressed on cardiomyocytes.59 In response to pressure overload NRG-1/ErbB expression first increases during the compensatory stage of concentric growth and then decreases as the heart begins to fail.59, 60

The link between these changes in NRG-1/ErbB expression and hypertrophy/heart failure progression is not clear. Potential mechanism include direct stimulation of cardiomyocyte hypertrophy via Erk1/2 and PI3-kinase/Akt pathways61, direct myocardial toxicity via mitochondrial and reactive oxygen species pathways 62 or possibly effects on the vasculature. A newly described mechanism of Erk1/2 autophosphorylation at Thr188 integrates a crosstalk between G protein signaling and NRG-1/ErbB pathway in response to pressure overload. As result of NRG-1 stimulation, activated ErbB recruits Gβα to Raf1-MAP kinase cascade that in turn causes intermolecular autophosphorylation of Erk1/2 at Thr188, Erk1/2 nuclear translocation and activation of hypertrophic growth program.63 Interestingly, increasing NRG-1/ErbB4 signaling by NRG-1 injection or ErbB4 expression may induce cardiomyocyte proliferation and promote myocardial regeneration after myocardial infarction. 64

Another recently identified important neurohumoral regulator secreted by the endothelium is apelin. Apelin acts via its GPCR receptor APJ and likely plays an important role in cardiovascular physiology and pathology by opposing actions of the rennin-angiotensin system.65 Thus, while AngII increases vascular tone and raises blood pressure, apelin promotes vasodilation through nitric-oxide dependent mechanism and its expression is induced in response to hypoxia in the ischemic heart.66, 67 In the heart, apelin is primarily expressed in the endothelium while APJ is expressed on cardiomyocyte, smooth muscle cells and endothelial cells suggesting a paracrine mode of signaling.68–71

Several reports suggest apelin contribution to the pathophysiology of human heart failure and associate its deficit with myocardial decompensation.68, 72–74 Interestingly, in a hypertensive cardiac hypertrophy the levels of apelin and APJ are maintained during compensated stage and decline as heart failure sets in.75 This may be due to an inhibitory effect of AngII since an AT1R blocker telmisartan restores apelin/APJ expression.

3. The Fibroblasts

Cardiac fibroblasts account for two thirds of cell mass of the heart and produce the majority of extracellular matrix (ECM) proteins including fibronectin, laminin, collagen I and III in the interstitium and around the blood vessels. Fibroblasts can sense and respond to biomechanical stress.76 A number of humoral factors can affect fibroblast activation and deposition of ECM including AngII, ET-1, TGF-β, FGF2, and IGF-1.77–79 The resultant fibrosis can alter intercellular crosstalk and impair myocyte contractility, oxygenation, and metabolism. It can also result in fibroblasts differentiating into myofibroblasts, cells that express smooth muscle type contractile proteins and exhibit increased proliferative and secretory properties.80

In addition to stimulation of proliferation of resident fibroblasts, cardiac fibrosis may also result in endothelial cells undergoing endothelial-mesenchymal transformation (EndMT) and contributing in this manner to the total pool of cardiac fibroblasts.81 This process is mediated by TGF-β1 and can be inhibited by bone morphogenic protein 7 (BMP-7), a TGF-β superfamily member known to antagonize TGF-β signaling.81, 82

Bidirectional fibroblasts-cardiomyocytes crosstalk plays a pivotal role in myocardial hypertrophy. AngII, via AT1 receptor, induces TGF-β expression by cardiomyocytes and cardiac fibroblasts. TGF-β, in turn, promotes cardiac hypertrophy by activation of Smad proteins and TGFβ-activated kinase-1 (TAK1). At the same time, it also induces fibroblast proliferation and deposition of ECM proteins leading to fibrosis as described above.71 Recently, connective tissue growth factor (CTGF), a TGF-β activated factor, has been associated specifically with fibroblast proliferation and ECM production in the setting of myocardial fibrosis.83 CTGF is expressed by cardiac fibroblasts and cardiomyocytes and its expression is negatively regulated by two cardiac microRNAs (miRNAs), miR-133 and miR-30.84 While miR-133 is expressed specifically in cardiomyocytes, miR-30 is expressed in both cardiac fibroblasts and myocytes. MiR-133 knockout mice develop excessive fibrosis and heart failure while miR-133 knockdown also causes cardiac hypertrophy with impaired cardiac function.85, 86 These findings suggest that the reduction of miR-133 expression de-represses pro-hypertrophic program in cardiomyocytes and supports cardiomyocyte-cardiac fibroblasts crosstalk in promoting fibrosis in the heart.

Interestingly, while communications between cardiac fibroblasts and myocytes promote myocyte hypertrophy in the adult heart, they promote myocyte proliferation during embryonic development. The latter is thought to be mediated in part by embryonic cardiac fibroblasts secretion of fibronectin, collagen, and heparin-binding EGF-like growth factor that collaboratively interact and promote cardiomyocyte proliferation via β1- integrin signaling. 87 Thus, a switch in the fibroblast genetic program allows them to drive cardiomyocyte proliferation during embryonic development and myocyte hypertrophy in postnatal life.

4. Cell-Matrix Interaction and Adhesion-Associated Molecules in Cardiac Crosstalk

One of the most important ways of transducing a mechanical load to the ventricle is by altering cell adhesion to the extracellular matrix.88 Integrins, together with a number of associated cytoskeletal proteins, connect the sarcomeric contractile apparatus to the extracellular matrix across the plasma membrane and trigger intracellular signaling pathways that activate the cardiomyocyte hypertrophy program. Overexpression of a muscle-specific integrin isoform β1D in neonatal cardiomyocytes in vitro can augment the hypertrophic response induced by α1 adrenergic stimulation while suppression of integrin signaling inhibits it.89 Moreover, cardiac myocyte-specific deletion of β1 integrin results in an abnormal cardiac function and impaired compensatory response to pressure overload induced stress.90

Integrins work in concert with an array of effectors including focal adhesion kinase (FAK), tyrosine phosphatases such as Shp2, and small GTPases such as Ras and Rho that can activate Akt and MAPK signaling pathways. Thus Shp2 negatively controls FAK activation and limits hypertrophic growth by modulating the Akt/mTOR signaling pathway91, 92 while Cdc42, a member of the Rho family of small GTPases, can act as an antihypertrophic switch by activating JNK signaling thereby reducing NFAT transcriptional activity in response to pressure overload.93 Integrins can also signal via a FAK related non-kinase (FRNK) that has the ability to buffer FAK signaling, attenuating cardiac hypertrophy.94 Several adaptor molecules involved in integrin-mediated signal were shown to be essential for hypertrophic response. For example, melusin interaction with the integrin β1 cytoplasmic domain is required for phosphorylation of glycogen synthase kinase-3β that is needed for prevention of heart failure in response to chronic pressure overload.95

As the result of a crosstalk between integrin and growth factors signaling pathways a complex synergistic mechanism controls the hypertrophic process.96 Thus, Ang II and TGF-β stimulate integrin expression and localization,97 while integrins in turn regulate TGF-β expression.98 Furthermore, angiopoientin-1 (an endothelial cell-specific regulator of vessel maturation) reduces cardiac hypertrophy by binding to integrins and activating integrin-linked kinase (ILK) and Akt/MAPK pathways in cardiomyocytes.99

In addition, integrin-mediated cell adhesion can be modulated by membrane-associated proteins such as the ADAMs (a desintegrin and metalloprotease) that can cleave specific matrix proteins and mediate adhesion complex shedding. ADAMs can also modulate expression and function of growth factor receptors, and thus affect a wide variety of biological processes that are important in the heart, including angiogenesis and cardiac hypertrophy. Inhibition of ADAM12 function by a specific metalloproteinase inhibitor, for example, attenuates cardiac hypertrophy in mice, likely due to inhibition of ADAM12-mediated shedding of heparin binding epidermal growth factor receptor.100

5. Long Distance Cell-Cell Communications

A myocardial hypertrophic response and the transition to heart failure are not solely determined by cell-cell communications in the heart and are also controlled by endocrine signaling. While some of these, such as aldosterone and the renin-angiotensin system are well known, others are just beginning to be understood.

5.1. Adiponectin

Adiponectin, a circulating adipose tissue-derived cytokine that is down-regulated in patients with obesity, has been recently described as a cardioprotective factor.101, 102 This function of adiponectin in a hypertrophy-induced response to hemodynamic stress in the heart is related to increased AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) signaling and reduced activation of Erk pathway 103 While adiponectin may induce angiogenesis in the hindlimb ischemia model,104 no comparable effect has been observed in the myocardium suggesting that the protective effect of adiponectin in this setting is related to its effect on cardiomyocytes.103

From a clinical stand point the role of adiponectin in preventing heart failure is controversial. Although obesity is a risk factor for the development of heart failure, a higher BMI and lower adiponectin levels were associated with an improved prognosis in patients with established chronic heart failure105 while higher levels of plasma adiponectin were associated with a lower risk of myocardial infarction in men.106, 107

5.2 Calcitonin Gene-Related Peptide (CGRP)

Recent studies have begun describing important roles played by endogenous regulatory peptides members of CGRP family, adrenomedullin (AM) and intermedin/adrenomedullin-2 (IMD). 108, 109 The calcitonin/CGRP family of peptides, widely distributed in various peripheral tissues, including heart, lung, kidney, the vasculature as well as in the central nervous system, induce multiple biological effects. Adrenomedullin is primarily secreted by vascular cells and functions as a local autocrine or paracrine mediator, as well as a circulating hormone capable of inducing vasodilation, diuresis and cardioprotection.108, 110 In mouse embryos, AM deficiency leads to lethality due to vascular fragility, severe hemorrhage and edema.111 In vivo and in vitro studies that AM inhibits myocyte hypertrophy, fibroblast proliferation and ECM production and improves heart contractility.108 while systemic infusion of AM is protective and beneficial in myocardial infarction, heart and renal failure.112

IMD shares similar cellular and tissue distribution with AM and its predominant localization in hypothalamus, pituitary and in kidney is consistent with the role in central and peripheral regulation of water-electrolyte homeostasis.109 IMD gene expression is upregulated in the failing heart suggesting a possible anti-hypertrophic effect.113

Conclusion

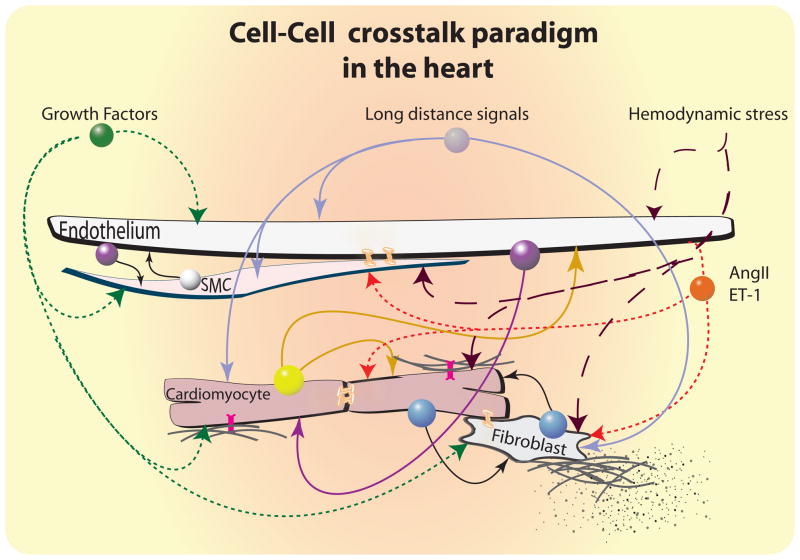

It is becoming evidently clear that in solid organs different cells types sense different stimuli and integrate their responses to them. Thus, no cell is an island, and this is particularly true in the heart. The many cellular “conversations” in cardiac tissues must be coordinated to ensure that the cell-cell crosstalk directs integrated biological responses to various stimuli (Figure 3). There are a number of communication channels that cells in the heart use to communicate with their neighbors. Of these, the most extensively studied are the paracrine and autocrine signaling that utilizes a long list of secreted factors such as VEGF, FGF, TGFβ, ET-1, AngII, PDGF, IGF, HGF, angiopoietins, NO, NRG-1, apelin, Fstl-1 and other. The cell-cell endocrine cross-talk from beyond heart boundaries using molecules such as adiponectin, and adrenomedullin/intermedin may also play a role in hypertrophic response and it is an important area of ongoing research. Other types of cell-cell communications that have been explored less extensively in the context of an integrative hypertrophic response include gap junctions-mediated cell-cell contacts, cell-matrix interactions and signaling through adhesion molecules including integrins that may modulate ventricular growth in crosstalk with circulating growth factors and other humoral mediators.

Figure 3.

Cellular crosstalk paradigms in the heart. A number of local and long-distance cell-cell communications contribute to maintenance of normal cardiac homeostasis and to responses to hypertrophic stimuli. These include paracrine/autocrine and endocrine signals, direct cell-cell contacts via gap junction, and cell- matrix interactions between cells of the coronary vasculature, cardiomyocytes, fibroblasts and probably other cell types, including tissue-resident stem cells. Perturbations in the balance of this network during sustained hemodynamic stress can lead to a variety of pathological sequelae, including heart failure due to inadequate vascular compensation for myocyte hypertrophy, and the development of cardiac fibrosis as a consequence of fibroblast proliferation and remodeling of the extracellular matrix.  Growth factors (e.g. IGF, FGF, HB-EGF, PDGF, HGF, VEGF, etc.);

Growth factors (e.g. IGF, FGF, HB-EGF, PDGF, HGF, VEGF, etc.);  Stress enhancers (e.g. AngII, ET-1, etc.);

Stress enhancers (e.g. AngII, ET-1, etc.);  Endothelium signals (e.g. NO, NRG-1, apelin, angiopoientin-1, prostacyclin, etc.);

Endothelium signals (e.g. NO, NRG-1, apelin, angiopoientin-1, prostacyclin, etc.);  SMC (e.g. VEGF, angiopoientin, etc);

SMC (e.g. VEGF, angiopoientin, etc);  Cardiomyocyte signals (e.g. Fslt-1, VEGF, FGF2, adenosine, etc.);

Cardiomyocyte signals (e.g. Fslt-1, VEGF, FGF2, adenosine, etc.);  Cardiomyocyte-Fibroblast signals (e.g. TGF-β, CTGF, etc.);

Cardiomyocyte-Fibroblast signals (e.g. TGF-β, CTGF, etc.);  endocrine signals (e.g. adiponectin, adrenomedullin, intermedin, aldosterone etc.);

endocrine signals (e.g. adiponectin, adrenomedullin, intermedin, aldosterone etc.);  integrins;

integrins;  connexins.

connexins.

One particularly important aspect of cell-cell interactions in the heart that is just beginning to be appreciated is the bi-directional signaling between the myocytes and the endothelium. A further understanding how changes in endothelial cell mass affect a paracrine hypertrophic signal would be of great interest in formulating new therapeutic angiogenesis approaches to the treatment of heart failure.

Acknowledgments

Funding Sources

Supported in part by American Heart Association Scientist Development Grant 0935107N (Dr Tirziu) and NIH grants HL75616 (Dr Giordano) and HL84619 and HL 53793 (Dr Simons) and NIH grants HL62289 and 53793 (MS).

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: None

References

- 1.Lloyd-Jones D, Adams R, Carnethon M, De Simone G, Ferguson TB, Flegal K, Ford E, Furie K, Go A, Greenlund K, Haase N, Hailpern S, Ho M, Howard V, Kissela B, Kittner S, Lackland D, Lisabeth L, Marelli A, McDermott M, Meigs J, Mozaffarian D, Nichol G, O’Donnell C, Roger V, Rosamond W, Sacco R, Sorlie P, Stafford R, Steinberger J, Thom T, Wasserthiel-Smoller S, Wong N, Wylie-Rosett J, Hong Y. Heart disease and stroke statistics--2009 update: a report from the American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Circulation. 2009;119:480–486. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.191259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Duncker DJ, Bache RJ. Regulation of coronary blood flow during exercise. Physiol Rev. 2008;88:1009–1086. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00045.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hudlicka O, Brown M, Egginton S. Angiogenesis in skeletal and cardiac muscle. Physiol Rev. 1992;72:369–417. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1992.72.2.369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fagard R. Athlete’s heart. Heart. 2003;89:1455–1461. doi: 10.1136/heart.89.12.1455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Molkentin JD, Dorn GW., 2nd Cytoplasmic signaling pathways that regulate cardiac hypertrophy. Annu Rev Physiol. 2001;63:391–426. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.63.1.391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dorn GW., 2nd The fuzzy logic of physiological cardiac hypertrophy. Hypertension. 2007;49:962–970. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.106.079426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Diwan A, Dorn GW., 2nd Decompensation of cardiac hypertrophy: cellular mechanisms and novel therapeutic targets. Physiology (Bethesda) 2007;22:56–64. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00033.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bu L, Jiang X, Martin-Puig S, Caron L, Zhu S, Shao Y, Roberts DJ, Huang PL, Domian IJ, Chien KR. Human ISL1 heart progenitors generate diverse multipotent cardiovascular cell lineages. Nature. 2009;460:113–117. doi: 10.1038/nature08191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dorn GW, 2nd, Robbins J, Sugden PH. Phenotyping hypertrophy: eschew obfuscation. Circ Res. 2003;92:1171–1175. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000077012.11088.BC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Heineke J, Molkentin JD. Regulation of cardiac hypertrophy by intracellular signalling pathways. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2006;7:589–600. doi: 10.1038/nrm1983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shohet RV, Kisanuki YY, Zhao XS, Siddiquee Z, Franco F, Yanagisawa M. Mice with cardiomyocyte-specific disruption of the endothelin-1 gene are resistant to hyperthyroid cardiac hypertrophy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:2088–2093. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307159101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kedzierski RM, Grayburn PA, Kisanuki YY, Williams CS, Hammer RE, Richardson JA, Schneider MD, Yanagisawa M. Cardiomyocyte-specific endothelin A receptor knockout mice have normal cardiac function and an unaltered hypertrophic response to angiotensin II and isoproterenol. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:8226–8232. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.22.8226-8232.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Steinberg TH. Gap junction function: the messenger and the message. Am J Pathol. 1998;152:851–854. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lo CW. Role of gap junctions in cardiac conduction and development: insights from the connexin knockout mice. Circ Res. 2000;87:346–348. doi: 10.1161/01.res.87.5.346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Reaume AG, de Sousa PA, Kulkarni S, Langille BL, Zhu D, Davies TC, Juneja SC, Kidder GM, Rossant J. Cardiac malformation in neonatal mice lacking connexin43. Science. 1995;267:1831–1834. doi: 10.1126/science.7892609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gu H, Smith FC, Taffet SM, Delmar M. High incidence of cardiac malformations in connexin40-deficient mice. Circ Res. 2003;93:201–206. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000084852.65396.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Eckardt D, Kirchhoff S, Kim JS, Degen J, Theis M, Ott T, Wiesmann F, Doevendans PA, Lamers WH, de Bakker JM, van Rijen HV, Schneider MD, Willecke K. Cardiomyocyte-restricted deletion of connexin43 during mouse development. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2006;41:963–971. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2006.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Severs NJ, Bruce AF, Dupont E, Rothery S. Remodelling of gap junctions and connexin expression in diseased myocardium. Cardiovasc Res. 2008;80:9–19. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvn133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kieken F, Mutsaers N, Dolmatova E, Virgil K, Wit AL, Kellezi A, Hirst-Jensen BJ, Duffy HS, Sorgen PL. Structural and molecular mechanisms of gap junction remodeling in epicardial border zone myocytes following myocardial infarction. Circ Res. 2009;104:1103–1112. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.190454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Huang GY, Cooper ES, Waldo K, Kirby ML, Gilula NB, Lo CW. Gap junction-mediated cell-cell communication modulates mouse neural crest migration. J Cell Biol. 1998;143:1725–1734. doi: 10.1083/jcb.143.6.1725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu S, Liu F, Schneider AE, St Amand T, Epstein JA, Gutstein DE. Distinct cardiac malformations caused by absence of connexin 43 in the neural crest and in the non-crest neural tube. Development. 2006;133:2063–2073. doi: 10.1242/dev.02374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li WE, Waldo K, Linask KL, Chen T, Wessels A, Parmacek MS, Kirby ML, Lo CW. An essential role for connexin43 gap junctions in mouse coronary artery development. Development. 2002;129:2031–2042. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.8.2031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rook MB, van Ginneken AC, de Jonge B, el Aoumari A, Gros D, Jongsma HJ. Differences in gap junction channels between cardiac myocytes, fibroblasts, and heterologous pairs. Am J Physiol. 1992;263:C959–977. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1992.263.5.C959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xie Y, Garfinkel A, Weiss JN, Qu Z. Cardiac Alternans Induced by Fibroblast-Myocyte Coupling: Mechanistic Insights from Computational Models. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2009;297:H775–H784. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00341.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ming J, Li T, Zhang Y, Xu J, Yang G, Liu L. Regulatory effects of myoendothelial gap junction on vascular reactivity after hemorrhagic shock in rats. Shock. 2009;31:80–86. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0b013e31817d3eF2-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Beny JL, Pacicca C. Bidirectional electrical communication between smooth muscle and endothelial cells in the pig coronary artery. Am J Physiol. 1994;266:H1465–1472. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1994.266.4.H1465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kwak BR, Mulhaupt F, Veillard N, Gros DB, Mach F. Altered pattern of vascular connexin expression in atherosclerotic plaques. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2002;22:225–230. doi: 10.1161/hq0102.104125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brisset AC, Isakson BE, Kwak BR. Connexins in vascular physiology and pathology. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2009;11:267–282. doi: 10.1089/ars.2008.2115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cowan DB, Lye SJ, Langille BL. Regulation of vascular connexin43 gene expression by mechanical loads. Circ Res. 1998;82:786–793. doi: 10.1161/01.res.82.7.786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zemljic-Harpf AE, Miller JC, Henderson SA, Wright AT, Manso AM, Elsherif L, Dalton ND, Thor AK, Perkins GA, McCulloch AD, Ross RS. Cardiac-myocyte-specific excision of the vinculin gene disrupts cellular junctions, causing sudden death or dilated cardiomyopathy. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27:7522–7537. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00728-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhou M, Sutliff RL, Paul RJ, Lorenz JN, Hoying JB, Haudenschild CC, Yin M, Coffin JD, Kong L, Kranias EG, Luo W, Boivin GP, Duffy JJ, Pawlowski SA, Doetschman T. Fibroblast growth factor 2 control of vascular tone. Nat Med. 1998;4:201–207. doi: 10.1038/nm0298-201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Giordano FJ, Gerber HP, Williams SP, VanBruggen N, Bunting S, Ruiz-Lozano P, Gu Y, Nath AK, Huang Y, Hickey R, Dalton N, Peterson KL, Ross J, Jr, Chien KR, Ferrara N. A cardiac myocyte vascular endothelial growth factor paracrine pathway is required to maintain cardiac function. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:5780–5785. doi: 10.1073/pnas.091415198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li J, Brown LF, Hibberd MG, Grossman JD, Morgan JP, Simons M. VEGF, flk-1, and flt-1 expression in a rat myocardial infarction model of angiogenesis. Am J Physiol. 1996;270:H1803–1811. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1996.270.5.H1803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sellke FW, Wang SY, Stamler A, Lopez JJ, Li J, Li J, Simons M. Enhanced microvascular relaxations to VEGF and bFGF in chronically ischemic porcine myocardium. Am J Physiol. 1996;271:H713–720. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1996.271.2.H713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shiojima I, Yefremashvili M, Luo Z, Kureishi Y, Takahashi A, Tao J, Rosenzweig A, Kahn CR, Abel ED, Walsh K. Akt signaling mediates postnatal heart growth in response to insulin and nutritional status. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:37670–37677. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M204572200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Matsui T, Li L, Wu JC, Cook SA, Nagoshi T, Picard MH, Liao R, Rosenzweig A. Phenotypic spectrum caused by transgenic overexpression of activated Akt in the heart. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:22896–22901. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M200347200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shiojima I, Sato K, Izumiya Y, Schiekofer S, Ito M, Liao R, Colucci WS, Walsh K. Disruption of coordinated cardiac hypertrophy and angiogenesis contributes to the transition to heart failure. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:2108–2118. doi: 10.1172/JCI24682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Walsh K, Shiojima I. Cardiac growth and angiogenesis coordinated by intertissue interactions. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:3176–3179. doi: 10.1172/JCI34126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Oshima Y, Ouchi N, Sato K, Izumiya Y, Pimentel DR, Walsh K. Follistatin-like 1 is an Akt-regulated cardioprotective factor that is secreted by the heart. Circulation. 2008;117:3099–3108. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.767673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ouchi N, Oshima Y, Ohashi K, Higuchi A, Ikegami C, Izumiya Y, Walsh K. Follistatin-like 1, a secreted muscle protein, promotes endothelial cell function and revascularization in ischemic tissue through a nitric oxide synthesis-dependent mechanism. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:32802–32811. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M803440200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ouchi N, Asaumi Y, Ohashi K, Higuchi A, Sono-Romanelli S, Oshima Y, Walsh K. DIP2A Functions as a FSTL1 Receptor. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:7127–7134. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.069468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Giordano FJ. Oxygen, oxidative stress, hypoxia, and heart failure. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:500–508. doi: 10.1172/JCI200524408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Semenza GL. HIF-1, O(2), and the 3 PHDs: how animal cells signal hypoxia to the nucleus. Cell. 2001;107:1–3. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00518-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Heineke J, Auger-Messier M, Xu J, Oka T, Sargent MA, York A, Klevitsky R, Vaikunth S, Duncan SA, Aronow BJ, Robbins J, Crombleholme TM, Molkentin JD. Cardiomyocyte GATA4 functions as a stress-responsive regulator of angiogenesis in the murine heart. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:3198–3210. doi: 10.1172/JCI32573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lopez JJ, Laham RJ, Carrozza JP, Tofukuji M, Sellke FW, Bunting S, Simons M. Hemodynamic effects of intracoronary VEGF delivery: evidence of tachyphylaxis and NO dependence of response. Am J Physiol. 1997;273:H1317–1323. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1997.273.3.H1317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tirziu D, Simons M. Endothelium as master regulator of organ development and growth. Vascul Pharmacol. 2009;50:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.vph.2008.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tomanek RJ, Busch TL. Coordinated capillary and myocardial growth in response to thyroxine treatment. Anat Rec. 1998;251:44–49. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0185(199805)251:1<44::AID-AR8>3.0.CO;2-E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tomanek RJ, Doty MK, Sandra A. Early coronary angiogenesis in response to thyroxine: growth characteristics and upregulation of basic fibroblast growth factor. Circ Res. 1998;82:587–593. doi: 10.1161/01.res.82.5.587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tirziu D, Chorianopoulos E, Moodie KL, Palac RT, Zhuang ZW, Tjwa M, Roncal C, Eriksson U, Fu Q, Elfenbein A, Hall AE, Carmeliet P, Moons L, Simons M. Myocardial hypertrophy in the absence of external stimuli is induced by angiogenesis in mice. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:3188–3197. doi: 10.1172/JCI32024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tirziu D, Simons M. Endothelium-driven myocardial growth or nitric oxide at the crossroads. Trends Cardiovasc Med. 2008;18:299–305. doi: 10.1016/j.tcm.2009.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hu RG, Sheng J, Qi X, Xu Z, Takahashi TT, Varshavsky A. The N-end rule pathway as a nitric oxide sensor controlling the levels of multiple regulators. Nature. 2005;437:981–986. doi: 10.1038/nature04027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Karpanen T, Bry M, Ollila HM, Seppanen-Laakso T, Liimatta E, Leskinen H, Kivela R, Helkamaa T, Merentie M, Jeltsch M, Paavonen K, Andersson LC, Mervaala E, Hassinen IE, Yla-Herttuala S, Oresic M, Alitalo K. Overexpression of vascular endothelial growth factor-B in mouse heart alters cardiac lipid metabolism and induces myocardial hypertrophy. Circ Res. 2008;103:1018–1026. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.178459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.May D, Gilon D, Djonov V, Itin A, Lazarus A, Gordon O, Rosenberger C, Keshet E. Transgenic system for conditional induction and rescue of chronic myocardial hibernation provides insights into genomic programs of hibernation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:282–287. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707778105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Izumiya Y, Shiojima I, Sato K, Sawyer DB, Colucci WS, Walsh K. Vascular endothelial growth factor blockade promotes the transition from compensatory cardiac hypertrophy to failure in response to pressure overload. Hypertension. 2006;47:887–893. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000215207.54689.31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sano M, Minamino T, Toko H, Miyauchi H, Orimo M, Qin Y, Akazawa H, Tateno K, Kayama Y, Harada M, Shimizu I, Asahara T, Hamada H, Tomita S, Molkentin JD, Zou Y, Komuro I. p53-induced inhibition of Hif-1 causes cardiac dysfunction during pressure overload. Nature. 2007;446:444–448. doi: 10.1038/nature05602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Dorn GW., 2nd Myocardial angiogenesis: its absence makes the growing heart founder. Cell Metab. 2007;5:326–327. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2007.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Meyer D, Birchmeier C. Multiple essential functions of neuregulin in development. Nature. 1995;378:386–390. doi: 10.1038/378386a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gassmann M, Casagranda F, Orioli D, Simon H, Lai C, Klein R, Lemke G. Aberrant neural and cardiac development in mice lacking the ErbB4 neuregulin receptor. Nature. 1995;378:390–394. doi: 10.1038/378390a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lemmens K, Segers VF, Demolder M, De Keulenaer GW. Role of neuregulin-1/ErbB2 signaling in endothelium-cardiomyocyte cross-talk. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:19469–19477. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M600399200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lemmens K, Doggen K, De Keulenaer GW. Role of neuregulin-1/ErbB signaling in cardiovascular physiology and disease: implications for therapy of heart failure. Circulation. 2007;116:954–960. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.690487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Baliga RR, Pimental DR, Zhao YY, Simmons WW, Marchionni MA, Sawyer DB, Kelly RA. NRG-1-induced cardiomyocyte hypertrophy. Role of PI-3-kinase, p70(S6K), and MEK-MAPK-RSK. Am J Physiol. 1999;277:H2026–2037. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1999.277.5.H2026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Gordon LI, Burke MA, Singh AT, Prachand S, Lieberman ED, Sun L, Naik TJ, Prasad SV, Ardehali H. Blockade of the erbB2 receptor induces cardiomyocyte death through mitochondrial and reactive oxygen species-dependent pathways. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:2080–2087. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M804570200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lorenz K, Schmitt JP, Schmitteckert EM, Lohse MJ. A new type of ERK1/2 autophosphorylation causes cardiac hypertrophy. Nat Med. 2009;15:75–83. doi: 10.1038/nm.1893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bersell K, Arab S, Haring B, Kuhn B. Neuregulin1/ErbB4 signaling induces cardiomyocyte proliferation and repair of heart injury. Cell. 2009;138:257–270. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.04.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ashley E, Chun HJ, Quertermous T. Opposing cardiovascular roles for the angiotensin and apelin signaling pathways. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2006;41:778–781. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2006.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Chun HJ, Ali ZA, Kojima Y, Kundu RK, Sheikh AY, Agrawal R, Zheng L, Leeper NJ, Pearl NE, Patterson AJ, Anderson JP, Tsao PS, Lenardo MJ, Ashley EA, Quertermous T. Apelin signaling antagonizes Ang II effects in mouse models of atherosclerosis. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:3343–3354. doi: 10.1172/JCI34871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sheikh AY, Chun HJ, Glassford AJ, Kundu RK, Kutschka I, Ardigo D, Hendry SL, Wagner RA, Chen MM, Ali ZA, Yue P, Huynh DT, Connolly AJ, Pelletier MP, Tsao PS, Robbins RC, Quertermous T. In vivo genetic profiling and cellular localization of apelin reveals a hypoxia-sensitive, endothelial-centered pathway activated in ischemic heart failure. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2008;294:H88–98. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00935.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Chen MM, Ashley EA, Deng DX, Tsalenko A, Deng A, Tabibiazar R, Ben-Dor A, Fenster B, Yang E, King JY, Fowler M, Robbins R, Johnson FL, Bruhn L, McDonagh T, Dargie H, Yakhini Z, Tsao PS, Quertermous T. Novel role for the potent endogenous inotrope apelin in human cardiac dysfunction. Circulation. 2003;108:1432–1439. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000091235.94914.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kleinz MJ, Davenport AP. Immunocytochemical localization of the endogenous vasoactive peptide apelin to human vascular and endocardial endothelial cells. Regul Pept. 2004;118:119–125. doi: 10.1016/j.regpep.2003.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kleinz MJ, Skepper JN, Davenport AP. Immunocytochemical localisation of the apelin receptor, APJ, to human cardiomyocytes, vascular smooth muscle and endothelial cells. Regul Pept. 2005;126:233–240. doi: 10.1016/j.regpep.2004.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Rosenkranz S. TGF-beta1 and angiotensin networking in cardiac remodeling. Cardiovasc Res. 2004;63:423–432. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2004.04.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Foldes G, Horkay F, Szokodi I, Vuolteenaho O, Ilves M, Lindstedt KA, Mayranpaa M, Sarman B, Seres L, Skoumal R, Lako-Futo Z, deChatel R, Ruskoaho H, Toth M. Circulating and cardiac levels of apelin, the novel ligand of the orphan receptor APJ, in patients with heart failure. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2003;308:480–485. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(03)01424-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Chong KS, Gardner RS, Morton JJ, Ashley EA, McDonagh TA. Plasma concentrations of the novel peptide apelin are decreased in patients with chronic heart failure. Eur J Heart Fail. 2006;8:355–360. doi: 10.1016/j.ejheart.2005.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Charo DN, Ho M, Fajardo G, Kawana M, Kundu RK, Sheikh AY, Finsterbach TP, Leeper NJ, Ernst KV, Chen MM, Ho YD, Chun HJ, Bernstein D, Ashley EA, Quertermous T. Endogenous regulation of cardiovascular function by apelin-APJ. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2009;297:H1904–1913. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00686.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Iwanaga Y, Kihara Y, Takenaka H, Kita T. Down-regulation of cardiac apelin system in hypertrophied and failing hearts: Possible role of angiotensin II-angiotensin type 1 receptor system. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2006;41:798–806. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2006.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.MacKenna D, Summerour SR, Villarreal FJ. Role of mechanical factors in modulating cardiac fibroblast function and extracellular matrix synthesis. Cardiovasc Res. 2000;46:257–263. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(00)00030-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Manabe I, Shindo T, Nagai R. Gene expression in fibroblasts and fibrosis: involvement in cardiac hypertrophy. Circ Res. 2002;91:1103–1113. doi: 10.1161/01.res.0000046452.67724.b8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Bujak M, Frangogiannis NG. The role of TGF-beta signaling in myocardial infarction and cardiac remodeling. Cardiovasc Res. 2007;74:184–195. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2006.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Bouzegrhane F, Thibault G. Is angiotensin II a proliferative factor of cardiac fibroblasts? Cardiovasc Res. 2002;53:304–312. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(01)00448-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Tomasek JJ, Gabbiani G, Hinz B, Chaponnier C, Brown RA. Myofibroblasts and mechano-regulation of connective tissue remodelling. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2002;3:349–363. doi: 10.1038/nrm809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Zeisberg EM, Tarnavski O, Zeisberg M, Dorfman AL, McMullen JR, Gustafsson E, Chandraker A, Yuan X, Pu WT, Roberts AB, Neilson EG, Sayegh MH, Izumo S, Kalluri R. Endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition contributes to cardiac fibrosis. Nat Med. 2007;13:952–961. doi: 10.1038/nm1613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Potenta S, Zeisberg E, Kalluri R. The role of endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition in cancer progression. Br J Cancer. 2008;99:1375–1379. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Chen MM, Lam A, Abraham JA, Schreiner GF, Joly AH. CTGF expression is induced by TGF- beta in cardiac fibroblasts and cardiac myocytes: a potential role in heart fibrosis. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2000;32:1805–1819. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.2000.1215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Duisters RF, Tijsen AJ, Schroen B, Leenders JJ, Lentink V, van der Made I, Herias V, van Leeuwen RE, Schellings MW, Barenbrug P, Maessen JG, Heymans S, Pinto YM, Creemers EE. miR-133 and miR-30 regulate connective tissue growth factor: implications for a role of microRNAs in myocardial matrix remodeling. Circ Res. 2009;104:170–178. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.182535. 176p following 178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Care A, Catalucci D, Felicetti F, Bonci D, Addario A, Gallo P, Bang ML, Segnalini P, Gu Y, Dalton ND, Elia L, Latronico MV, Hoydal M, Autore C, Russo MA, Dorn GW, 2nd, Ellingsen O, Ruiz-Lozano P, Peterson KL, Croce CM, Peschle C, Condorelli G. MicroRNA-133 controls cardiac hypertrophy. Nat Med. 2007;13:613–618. doi: 10.1038/nm1582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.van Rooij E, Olson EN. Searching for miR-acles in cardiac fibrosis. Circ Res. 2009;104:138–140. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.192492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Ieda M, Tsuchihashi T, Ivey KN, Ross RS, Hong TT, Shaw RM, Srivastava D. Cardiac fibroblasts regulate myocardial proliferation through beta1 integrin signaling. Dev Cell. 2009;16:233–244. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2008.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Lal H, Verma SK, Foster DM, Golden HB, Reneau JC, Watson LE, Singh H, Dostal DE. Integrins and proximal signaling mechanisms in cardiovascular disease. Front Biosci. 2009;14:2307–2334. doi: 10.2741/3381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Ross RS, Pham C, Shai SY, Goldhaber JI, Fenczik C, Glembotski CC, Ginsberg MH, Loftus JC. Beta1 integrins participate in the hypertrophic response of rat ventricular myocytes. Circ Res. 1998;82:1160–1172. doi: 10.1161/01.res.82.11.1160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Shai SY, Harpf AE, Babbitt CJ, Jordan MC, Fishbein MC, Chen J, Omura M, Leil TA, Becker KD, Jiang M, Smith DJ, Cherry SR, Loftus JC, Ross RS. Cardiac myocyte-specific excision of the beta1 integrin gene results in myocardial fibrosis and cardiac failure. Circ Res. 2002;90:458–464. doi: 10.1161/hh0402.105790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Marin TM, Clemente CF, Santos AM, Picardi PK, Pascoal VD, Lopes-Cendes I, Saad MJ, Franchini KG. Shp2 negatively regulates growth in cardiomyocytes by controlling focal adhesion kinase/Src and mTOR pathways. Circ Res. 2008;103:813–824. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.179754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Martin KA, Hwa J. Shp shape: FAKs about hypertrophy. Circ Res. 2008;103:776–778. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.186452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Maillet M, Lynch JM, Sanna B, York AJ, Zheng Y, Molkentin JD. Cdc42 is an antihypertrophic molecular switch in the mouse heart. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:3079–3088. doi: 10.1172/JCI37694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.DiMichele LA, Hakim ZS, Sayers RL, Rojas M, Schwartz RJ, Mack CP, Taylor JM. Transient expression of FRNK reveals stage-specific requirement for focal adhesion kinase activity in cardiac growth. Circ Res. 2009;104:1201–1208. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.195941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Brancaccio M, Fratta L, Notte A, Hirsch E, Poulet R, Guazzone S, De Acetis M, Vecchione C, Marino G, Altruda F, Silengo L, Tarone G, Lembo G. Melusin, a muscle-specific integrin beta1-interacting protein, is required to prevent cardiac failure in response to chronic pressure overload. Nat Med. 2003;9:68–75. doi: 10.1038/nm805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Ross RS. Molecular and mechanical synergy: cross-talk between integrins and growth factor receptors. Cardiovasc Res. 2004;63:381–390. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2004.04.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Thibault G, Lacombe MJ, Schnapp LM, Lacasse A, Bouzeghrane F, Lapalme G. Upregulation of alpha(8)beta(1)-integrin in cardiac fibroblast by angiotensin II and transforming growth factor-beta1. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2001;281:C1457–1467. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.2001.281.5.C1457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Wang D, Sun L, Zborowska E, Willson JK, Gong J, Verraraghavan J, Brattain MG. Control of type II transforming growth factor-beta receptor expression by integrin ligation. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:12840–12847. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.18.12840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Dallabrida SM, Ismail NS, Pravda EA, Parodi EM, Dickie R, Durand EM, Lai J, Cassiola F, Rogers RA, Rupnick MA. Integrin binding angiopoietin-1 monomers reduce cardiac hypertrophy. Faseb J. 2008;22:3010–3023. doi: 10.1096/fj.07-100966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Asakura M, Kitakaze M, Takashima S, Liao Y, Ishikura F, Yoshinaka T, Ohmoto H, Node K, Yoshino K, Ishiguro H, Asanuma H, Sanada S, Matsumura Y, Takeda H, Beppu S, Tada M, Hori M, Higashiyama S. Cardiac hypertrophy is inhibited by antagonism of ADAM12 processing of HB-EGF: metalloproteinase inhibitors as a new therapy. Nat Med. 2002;8:35–40. doi: 10.1038/nm0102-35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Ouchi N, Shibata R, Walsh K. Cardioprotection by adiponectin. Trends Cardiovasc Med. 2006;16:141–146. doi: 10.1016/j.tcm.2006.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Hopkins TA, Ouchi N, Shibata R, Walsh K. Adiponectin actions in the cardiovascular system. Cardiovasc Res. 2007;74:11–18. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2006.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Shibata R, Ouchi N, Ito M, Kihara S, Shiojima I, Pimentel DR, Kumada M, Sato K, Schiekofer S, Ohashi K, Funahashi T, Colucci WS, Walsh K. Adiponectin-mediated modulation of hypertrophic signals in the heart. Nat Med. 2004;10:1384–1389. doi: 10.1038/nm1137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Shibata R, Ouchi N, Kihara S, Sato K, Funahashi T, Walsh K. Adiponectin stimulates angiogenesis in response to tissue ischemia through stimulation of amp-activated protein kinase signaling. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:28670–28674. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M402558200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Kistorp C, Faber J, Galatius S, Gustafsson F, Frystyk J, Flyvbjerg A, Hildebrandt P. Plasma adiponectin, body mass index, and mortality in patients with chronic heart failure. Circulation. 2005;112:1756–1762. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.530972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Pischon T, Girman CJ, Hotamisligil GS, Rifai N, Hu FB, Rimm EB. Plasma adiponectin levels and risk of myocardial infarction in men. Jama. 2004;291:1730–1737. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.14.1730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Schulze MB, Shai I, Rimm EB, Li T, Rifai N, Hu FB. Adiponectin and future coronary heart disease events among men with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes. 2005;54:534–539. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.2.534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Kato J, Tsuruda T, Kitamura K, Eto T. Adrenomedullin: a possible autocrine or paracrine hormone in the cardiac ventricles. Hypertens Res. 2003;26 (Suppl):S113–119. doi: 10.1291/hypres.26.s113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Bell D, McDermott BJ. Intermedin (adrenomedullin-2): a novel counter-regulatory peptide in the cardiovascular and renal systems. Br J Pharmacol. 2008;153 (Suppl 1):S247–262. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0707494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Nishikimi T, Matsuoka H. Cardiac adrenomedullin: its role in cardiac hypertrophy and heart failure. Curr Med Chem Cardiovasc Hematol Agents. 2005;3:231–242. doi: 10.2174/1568016054368241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Ichikawa-Shindo Y, Sakurai T, Kamiyoshi A, Kawate H, Iinuma N, Yoshizawa T, Koyama T, Fukuchi J, Iimuro S, Moriyama N, Kawakami H, Murata T, Kangawa K, Nagai R, Shindo T. The GPCR modulator protein RAMP2 is essential for angiogenesis and vascular integrity. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:29–39. doi: 10.1172/JCI33022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Ishimitsu T, Ono H, Minami J, Matsuoka H. Pathophysiologic and therapeutic implications of adrenomedullin in cardiovascular disorders. Pharmacol Ther. 2006;111:909–927. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2006.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Hirose T, Totsune K, Mori N, Morimoto R, Hashimoto M, Nakashige Y, Metoki H, Asayama K, Kikuya M, Ohkubo T, Hashimoto J, Sasano H, Kohzuki M, Takahashi K, Imai Y. Increased expression of adrenomedullin 2/intermedin in rat hearts with congestive heart failure. Eur J Heart Fail. 2008;10:840–849. doi: 10.1016/j.ejheart.2008.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]