Abstract

Purpose

Determine cosmetic outcome and toxicity profile of intraoperative radiation delivered prior-to tumor excision for patients with early stage breast cancer.

Methods

Patients age 48 or older with ultrasound-visible invasive ductal cancers <3 cm and clinically negative lymph nodes were eligible for treatment on this IRB approved phase II clinical trial. Treatment planning ultrasound was used to select an electron energy and cone size sufficient to cover the tumor plus a 1.5–2.0 cm circumferential margin laterally and a 1 cm deep margin with the 90% isodose line. The dose was prescribed to a nominal 15 Gy and delivered using a Mobetron electron irradiator prior to tumor excision by segmental mastectomy. Physician and patient assessed cosmetic outcome and patient satisfaction were determined by questionnaire.

Results

From March 2003 to July 2007, seventy-one patients were treated with IORT. Fifty-six patients were evaluable with a median follow-up of 3.1 years (minimum 1 year). Physician and patient assessment of cosmesis was “good or excellent” (RTOG-cosmesis scale) in 45/56 (80%) and 32/42 (76%) of all patients, respectively. Eleven patients who received additional whole breast radiation had similar rates of good or excellent cosmesis (40/48 or 83% and 29/36 or 81%, respectively). Grade 1 or 2 acute toxicities were seen in 4/71 (6%) patients. No grade 3 or 4 toxicities or serious adverse events have been seen.

Conclusion

Intraoperative radiotherapy delivered to an in situ tumor is feasible with acceptable acute tolerance. Patient and physician assessment of the cosmetic outcome is good to excellent.

Keywords: breast cancer, accelerated partial breast irradiation, intraoperative radiation

Introduction

The standard of care for women undergoing breast conservation therapy (BCT) is segmental mastectomy followed by whole breast radiotherapy (WBRT). Yet, 15–20% of women undergoing BCT in the United States do not receive WBRT (1, 2) due to the high cost of treatment (3), logistical difficulties involved in daily radiotherapy (4), and difficulty with transportation from home to treatment centers (5, 6). Multiple randomized trials demonstrate that the addition of WBRT following lumpectomy reduces the risk for in-breast relapse and improves overall survival (reviewed in (7)). Accelerated partial breast irradiation (APBI), which delivers a high dose of radiation per fraction over a shorter time frame may increase the proportion of women receiving BCT-related radiation by minimizing barriers to therapy.

Multiple techniques for delivering APBI exist including three-dimensional conformal radiotherapy, stereotactic body radiotherapy, interstitial catheter-based brachytherapy, endocavitary brachytherapy, or intraoperative radiotherapy (IORT). Each has advantages and disadvantages and requires a substantial clinical expertise such that the optimal technique remains uncertain. All rely on limiting the irradiated volume to the region of the breast felt to be at highest risk for local failure.

IORT can be used to deliver APBI in a single fraction at the time of tumor excision. Veronesi and colleagues have the largest experience with IORT. They perform a standard quadrantectomy, reapproximate the breast parenchyma using sutures, and deliver IORT with a mobile linear accelerator (8, 9). While originally used to deliver the “boost” radiation, they have used IORT as the sole modality for small, low risk tumors. Other approaches to IORT that have been employed include using a spherical applicator to irradiate the post-operative wound cavity using low energy photons (10) or using an iridium-192 source and a quadrangular silastic breast applicator to deliver intraoperative brachytherapy (11).

These approaches to IORT have been criticized for problems regarding radiation dose distribution and confirmation of target coverage. To address these issues, we modified the Veronesi technique to deliver radiation prior to tumor excision. Using a preoperative ultrasound we define the target and optimize the dosimetry. We have previously reported our initial experience and described our technique (12, 13). We now report the primary outcome, cosmesis, of our single-institution, prospective phase II trial.

Materials and Methods

Patient Selection

Patients age 48 or older with clinically node negative, infiltrating ductal carcinoma less than three centimeters in greatest diameter and visible by pre-operative breast ultrasound were eligible for this prospective study (Figure 1). Patients with multicentric disease, bilateral breast cancer, contraindications to BCT, skin or chest wall involvement, ductal carcinoma in situ, invasive lobular carcinoma, or who had received neoadjuvant chemotherapy or prior irradiation to the involved breast were not eligible. The primary endpoint was to determine the rate of Good or Excellent cosmesis as measured by the RTOG cosmetic rating scale. We also wanted to demonstrate acceptable toxicities and that IORT is not inferior to brachytherapy APBI in cosmetic outcome. Ipsilateral breast recurrence was evaluated as a secondary endpoint and will be reported separately.

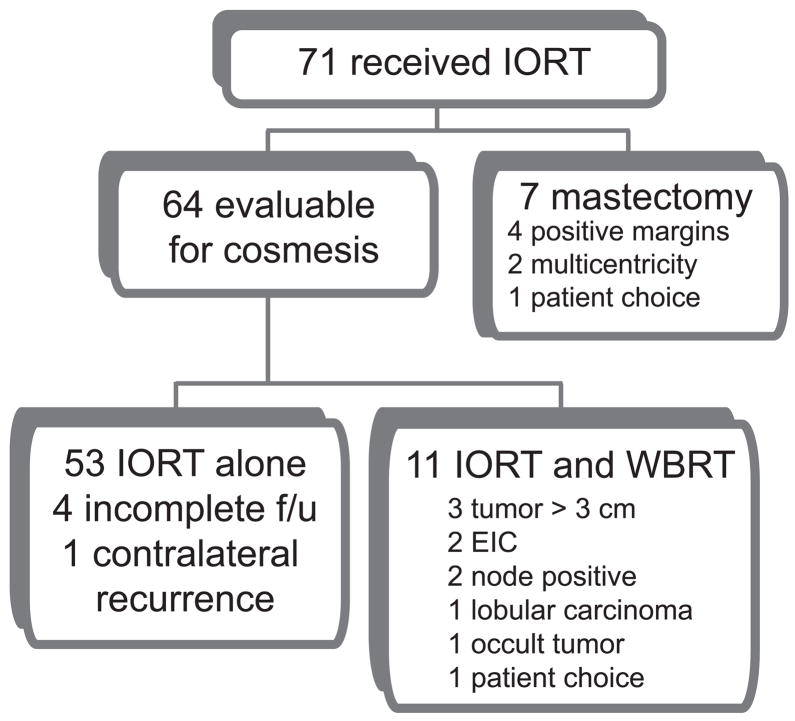

Figure 1.

Patient flow diagram.

Pre-operative, Surgical and Intra-operative Methods

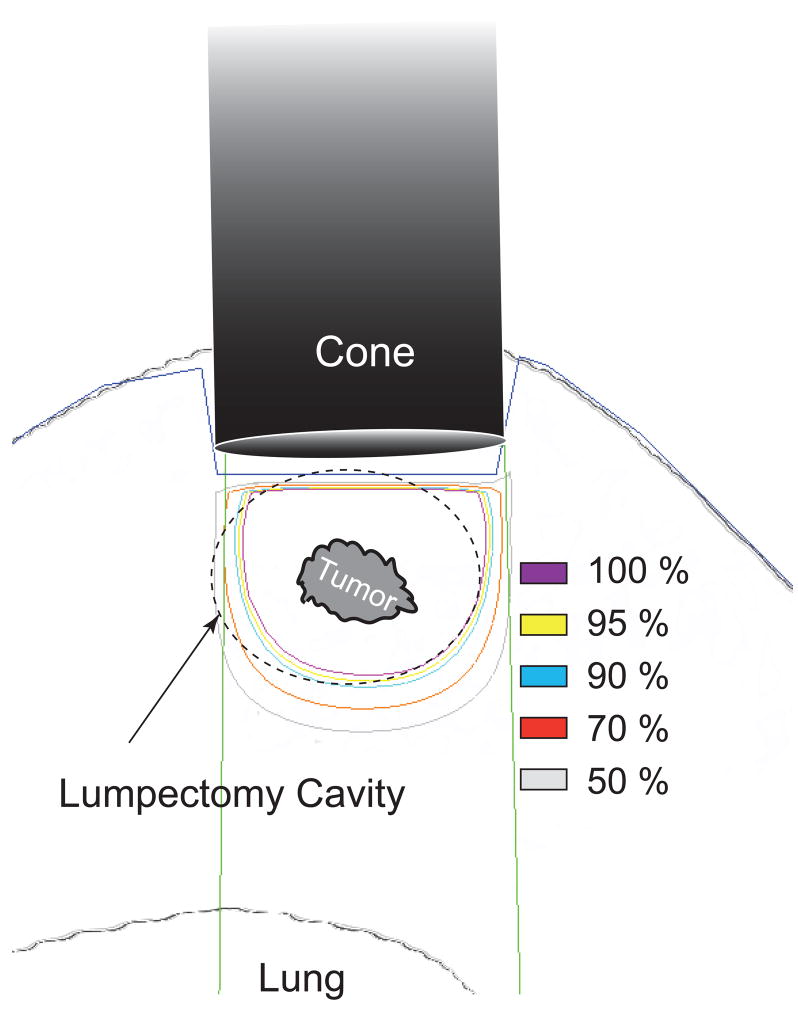

Briefly, ultrasound simulation is performed at the time of ultrasound-guided needle localization to determine the optimal angle of approach, minimize the skin-to-tumor distance, and maximize the tumor-to-lung distance. A cone necessary to encompass the tumor plus a 1.5–2.0 cm radial margin is selected. The depth from the skin to: 1) anterior tumor edge; 2) posterior tumor edge; and, 3) pleural surface are measured and an electron energy sufficient to deliver 1,500 cGy to the tumor is chosen (Figure 2). Chest wall dose was initially limited to 10 Gy, but revised to 15 Gy after Reitsamer reported no chest wall toxicity in patients treated with 10 Gy IORT electron boost and WBRT (14) and when our initial experience showed no acute toxicities following 10 Gy.

Figure 2.

Treatment delivery schematic. Target tissue is exposed by retracting the skin around the electron cone. An electron energy is chosen to provide 90% coverage to a point 1 cm deep to the tumor.

Following lymphatic mapping and sentinel lymphadenectomy, breast tissue overlying the tumor is exposed by making very thin skin flaps to adequately allow placement of the radiation cone. Skin edges are retracted from the radiation field and the radiation cone is positioned based on the angle of approach pre-determined by ultrasound guidance so that the edge is just abutting the breast tissue taking care not to compress or distort the breast tissue. Moist Raytek sponges are placed between the cone and the skin to act as a tissue-equivalent barrier able to absorb the low energy electrons scattered by the applicator itself.. The tumor is centered in the radiation field and placement is verified by the surgical and radiation oncologist. A mobile, self-shielded, linear accelerator (Mobetron, Intraop Medical, Norcross, GA) delivers the radiation following which the lumpectomy is performed in the standard fashion.

Post-operative treatment

Pathologic review confirming a priori defined features results in a recommendation for additional therapy. Patients with positive margins are recommended to undergo re-excision to negative margins or mastectomy. If an extensive intraductal component is present (i.e., DCIS representing >25% of the tumor and admixed-with and away-from the invasive component), tumor size is greater than 3 cm, or histology demonstrates infiltrating lobular carcinoma either WBRT (with IORT serving as boost) or mastectomy is recommended. Sentinel lymph-node positive patients underwent completion axillary lymph node dissection and either mastectomy or WBRT. Systemic therapy was recommended independent of the local therapy delivered.

Follow-up

Acute toxicity was evaluated 1 week and 3 months following IORT. Patients were evaluated every 3 months for the first 2 years, every 6 months for years 2–5, and annually thereafter for complications and recurrence. Cosmesis was assessed by both patient and physician written questionnaires using the RTOG breast toxicity scale and photographs taken at 6 months and annually.

Cosmesis and Toxicity Assessment

Cosmesis was assessed using a global cosmetic score that has been described by Wazer (15): EXCELLENT = perfect symmetry, no visible distortion or skin change; GOOD = slight skin distortion, retraction, or edema, any visible telangiectasia or mild hyperpigmentation; FAIR = moderate distortion of the nipple or breast symmetry, moderate hyperpigmentation, or prominent skin retraction, edema, or telangiectasia; POOR = marked distortion, edema, fibrosis, or severe hyperpigmentation. Cosmetic scoring was performed by a radiation oncologist, surgeon, or clinic nurse and scored as excellent, good, fair, or poor. Patient self-assessed cosmetic outcome was assessed by a similar scale. Patient satisfaction was assessed as: 1) totally satisfied, 2) not totally satisfied but would choose IORT again, 3) not totally satisfied and wound not choose IORT again, or 4) dissatisfied with IORT. Skin and subcutaneous toxicity were graded by a radiation oncologist according to common terminology criteria for adverse events (CTC-AE) version 3.0 (16). Toxicities directly, probably, or possibly related to the radiation were included.

Statistical Methods

The primary endpoint was to determine the physician assessment rate of Good or Excellent cosmesis as measured by the RTOG cosmetic rating scale. Patient assessment of cosmesis was also of interest. We were interested in comparing our cosmetic in situ IORT physician rate to the estimate of 85% for Good or Excellent outcomes, as reported in other trials of ABPI, to possibly demonstrate non-inferiority. We also monitored toxicity. In our study, we report on patients who required additional therapy, either mastectomy or WBRT, as well as patients who received only IORT, (given the somewhat slower than expected accrual).

To evaluate non-inferiority we set, a priori, a delta of 0.20 (or 20%), with a one-sided alpha level of 0.025. Therefore, to demonstrate non-inferiority, the lower bound of a 95% confidence interval for the difference in percentages needed to be greater than −20%. Exact 95% confidence intervals were calculated for each rate of interest (reported as percentages). Finally, we also report the weighted kappa statistic that measured the amount of agreement between physician and patient ratings at the 1 year time point. Statistical analyses were performed with SAS statistical software, Version 9.2, SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC.

This study was approved by the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (UNC) Committee on the Protection of the Rights of Human Subjects, UNC Institutional Review Board, and the Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center Protocol Review Committee.

Results

Patient characteristics

From March 2003 to July 2007, seventy-one patients underwent IORT on LCCC 0218 (Figure 1). As of June 30, 2009 median follow-up time was 3.1 years. Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics are reported (Table 1). Eighteen patients received additional therapy; eleven WBRT and seven mastectomy. Fifty-three patients were treated with IORT alone. Of those patients who received IORT, 32 were age 65 or older, 29 were ages 55–65, and 10 were ages 48–55. Our patient population had a similar age distribution to that of the comparison group from RTOG 95–17. In addition, we had slightly more patients with clinical T2 tumors (16/71 or 23% vs. 12%) and slightly fewer patients with lymph node positive disease than in the multi-institutional trial (7/71 or 10% vs. 20%) (17).

Table 1.

Patient characteristics.

| Characteristic | Received IORT n=71 (%) |

|---|---|

| Median age (range) | 64 (48–92) |

| Clinical Staging | |

| cT1a | 2 (2.8%) |

| cT1b | 18 (25%) |

| cT1c | 35 (49%) |

| cT2 (<3cm) | 16 (23%) |

| cN0 | 71 (100%) |

| Grade | |

| I | 25 (35%) |

| II | 24 (34%) |

| III | 22 (31%) |

| Markers | |

| ER+ | 54 (76%) |

| PR+ | 50 (70%) |

| HER2+ | 8 (11%) |

| ER+, PR+, HER2− | 46 (65%) |

| “triple negative” | 12 (17%) |

Treatment Delivery

Treatment characteristics are shown in Table 2. Maximum prescribed dose to provide adequate target coverage was 23.7 Gy. Median dose delivered was 15 Gy. Median tumor diameter on ultrasound was 1.2 cm corresponding to the median cone size of 5.5 cm. Seven patients were found to have metastatic breast cancer in the sentinel node. Twenty women were recommended to undergo re-excision for close or positive margins (Table 3). Thirty-three received adjuvant hormonal therapy and 17 received adjuvant chemotherapy.

Table 2.

Treatment characteristics (n=71).

| Characteristic | Median | Range |

|---|---|---|

| Tumor diameter on ultrasound (cm) | 1.2 | 0.5 – 2.4 |

| Skin to anterior tumor depth (cm) | 1 | 0.3 – 2.6 |

| Skin to posterior tumor depth (cm) | 2.2 | 0.15 – 5.1 |

| Skin to pleura depth (cm) | 3.9 | 1.6 – 6.7 |

| Dose (Gy) dmax | 15 | 14.3 – 23.7 |

| energy (MeV) | n | |

| 6 MeV | 1 | |

| 9 MeV | 26 | |

| 12 MeV | 44 | |

| Cone Size (cm) | ||

| 4.0 cm cone | 4 | |

| 4.5 cm cone | 8 | |

| 5.0 cm cone | 22 | |

| 5.5 cm cone | 15 | |

| 6.0 cm cone | 21 | |

| 7.0 cm cone | 1 | |

Table 3.

Additional treatment received.

| Characteristic | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Re-excision | 20 (28%) |

| Systemic chemotherapy | 17 (24%) |

| Hormonal therapy | 39 (55%) |

Cosmetic Outcome

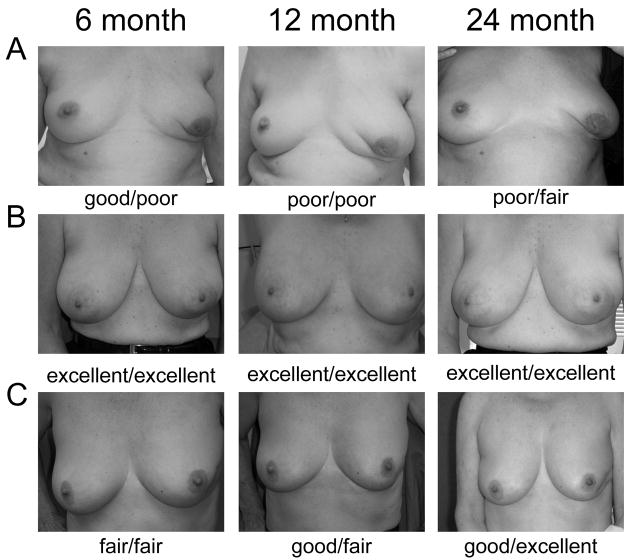

The primary endpoint of this study, cosmetic outcome was measured by both physician subjective evaluation and patient subjective evaluation. Representative examples of Good or Excellent and Fair or Poor outcomes are shown (Figure 3). At the 1 year follow-up visit, cosmetic outcome as assessed by physician was Good or Excellent in 45/56 or 80% (95% CI: 68–90%) of evaluable patients (Table 4). We expected that there would be somewhat worse cosmetic outcomes in the patients who received both IORT and WBRT. However, the rate of Good or Excellent cosmetic outcome in the entire cohort was not significantly different from that seen in those patients who received no WBRT, 40/48 (83%, 95% CI: 70–93%), or from those who did not undergo a re-excision 35/41 (85%, 95% CI: 71–94%). Cosmetic outcomes at the 2 year follow-up visit were similar to those at the 1 year visit (24/27, 89% G/E, 95% CI: 71–98%). While no statistically significant difference in cosmetic outcome over time was seen several patients subjectively demonstrated improved outcomes over time. We failed to detect a significant difference in cosmesis based on receipt of chemotherapy.

Figure 3.

Representative photographs of three patients who received only IORT (A and C) or IORT + WBRT (B) taken at the time of their 6 month, 1 year, and 2 year follow-up visit. Ratings shown represent physician (left) and patient (right) cosmetic outcome assessment.

Table 4.

Twelve month cosmetic outcome.

| Physician | Patient | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All, % (n=56) | no WBRT, % (n=48) | All, % (n=42) | no WBRT, % (n=36) | |

| Excellent | 59% (33) | 64% (31) | 43% (18) | 50% (18) |

| Good | 21% (12) | 19% (9) | 33% (14) | 31% (11) |

| Fair | 18% (10) | 17% (8) | 14% (6) | 11% (4) |

| Poor | 2% (1) | 0% (0) | 10% (4) | 8% (3) |

Patient-assessed cosmetic outcome was Good or Excellent in 32/42 or 76% (95% CI: 61–88%) of all patients (Table 4). Again, no significant difference between women who did not receive WBRT (29/36 G/E, 81%, 95% CI: 64–92%) or those who did not need a re-excision (26/31 G/E, 84%, 95% CI: 66–95%) was seen. No significant difference in cosmetic self-assessment over time was seen (data not shown). Physician and patient assessments of cosmetic outcomes showed moderate to almost substantial agreement as measured by the weighted kappa statistic of 0.60 (95%CI: 0.42–0.77).

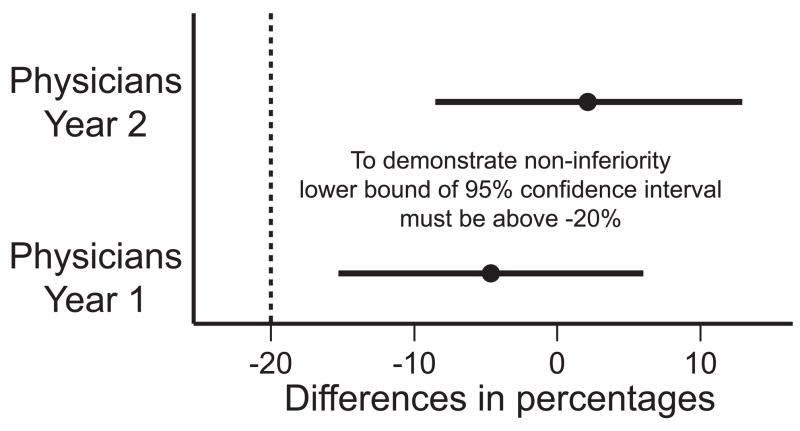

We were able to demonstrate the non-inferiority in physician assessment of Good or Excellent outcomes, both in 1 year and 2 year rates, when compared to the ‘a priori’ hypothesized rate of 85%. The 1 year rate was 45/56 or 80%. The 2 year rate was 34/39 or 87%. The difference in percentages (this study’s the 1 year and 2 year rates, with 85%) were −5% (95% CI: −15-6%) and 2% (95% CI: −8–13%) respectively. To demonstrate non-inferiority, the lower bound of a 95% confidence interval for the difference in percentages needed to be greater than −20%. Both were, with the 1 year lower bound of −15, and the 2 year lower bound of −8 being larger than −20. (Figure 4)

Figure 4.

Non-inferiority has been demonstrated by when comparing this study’s 1 and 2 year physician cosmetic assessment to the hypothesized rate of 85%. The lower bounds of the 95% confidence interval are above the ‘a prior’ set boundary of −20%.

Patient satisfaction

At 1 year follow-up, 35/40 or 88% (95% CI: 73–95%) of patients reported that they were “totally satisfied” with the IORT experience and only 2/40 patients or 5% (95% CI: 1–17%) stated that they would not choose IORT again (Table 5). The rate of totally satisfied patients was similar for those who received only IORT (32/35 or 91%, 95% CI: 77–98%) and those who did not require a re-excision (27/30 or 90%, 95% CI: 73–98%).

Table 5.

Twelve month patient satisfaction.

| Patient Satisfaction, % (n=40) | |

|---|---|

| Totally satisfied | 87% (35) |

| Not totally satisfied would choose IORT again | 8% (3) |

| Not totally satisfied would NOT choose IORT again | 5% (2) |

| Dissatisfied | 0% (0) |

Toxicities

There were no grade 3 or 4 toxicities and no serious adverse events related to the IORT. Grade 1 or 2 toxicity was seen in 4/71 or 6% (95% CI: 2–14%) of all patients (Table 6). Difficulty with wound healing and rib fractute was assessed prospectively. No patient had difficulty with wound healing noted, and no rib fractures have been observed in either the group that received IORT or the group that received IORT + WBRT. One of two women who underwent subsequent mastectomy with reconstruction had failure of a deep inferior epigastric perforator reconstruction necessitating an additional surgical procedure before obtaining a satisfactory reconstruction.

Table 6.

Toxicity profile associated with IORT

| Toxicity | # of patients | Grade |

|---|---|---|

| hematoma | 3 | 1 |

| breast pain | 1 | 2 |

Discussion

There are several potential techniques for giving IORT for early stage breast cancer. A spherical applicator delivering 30 to 50 kV x-rays (Intrabeam) has resulted in good or excellent cosmetic results in over 90% with tumor bed fibrosis noted in 27% of patients in one study (18, 19). A second method utilizes high dose rate brachytherapy with a custom applicator and has been pioneered by Sacchini and colleagues (11). Using a more quantitative photography based scoring system, about two-thirds of patients in this study had good cosmetic outcomes (20).

APBI with intraoperative electrons is based on work initially done giving an intraoperative boost treatment (21, 22). The Milan group, led by Veronesi, adopted this approach (23), but began using higher doses as a sole modality (9). Their technique differs in several important ways from ours. First, the surgical approach used is quadrantectomy an approach requiring significant clinical expertise to juxtapose the circumferential resection margins and other areas of subclinical disease into the target area prior to radiation delivery. In our study, the majority of patients underwent segmentectomy, an approach usually associated with better cosmetic outcomes than quadrantectomy (24). We have chosen to irradiate the tumor in situ using an approach that we believe allows better targeting of the tumor and normal tissues. Finally, they mobilize the remaining mammary gland to place an aluminum shield posterior to the tumor bed to minimize the dose of radiation received by the lung. Due to our desire to avoid manipulation of the tumor prior to radiation, we opted to treat without placement of a retromammary shield instead limiting the chest wall dose to 15 Gy. Clinical results on nearly 600 patients who received only IORT with a median follow-up of 2 years showed mild fibrosis in 3% of patients and lyponecrosis in 2.5% (8). Toxicity of our method (6% grade 1 or 2) is comparable to those described by Veronesi and colleagues.

Although nearly a quarter of our patients received subsequent systemic chemotherapy following surgical management and IORT we have not seen any patients with radiation recall reactions and did not note worse cosmetic outcomes as has been reported following other APBI techniques (25, 26). We have not seen any patients with lyponecrosis, perhaps due to limiting the volume of normal breast tissue irradiated by performing IORT prior to resection of the tumor.

Cosmetic outcomes with WBRT can be highly variable. The Danish Breast Study reported 72% excellent/satisfactory results while the Lyon and EORTC trials reported 85–90% excellent/good results (27–29). The most widely available technique for APBI is three-dimensional conformal radiotherapy (3D-CRT). In several published series, good/excellent cosmesis has been seen in about 90% of patients (30, 31). Interstitial catheter-based brachytherapy results in highly variable cosmesis; some groups report good/excellent cosmesis in most patients (17, 26, 32, 33) while others note poor cosmesis in up to 50% of patients (34, 35). Endocavitary brachytherapy, a technique popularized by the Mammosite device results in a good/excellent cosmetic result in 85–95% of patients (36, 37).

One difficulty in trials assessing cosmetic outcome is that there are no globally accepted, objective, quantifiable determinants of breast aesthetics. To allow valid comparisons to the RTOG studies we used the RTOG global cosmetic score as assessed by the treating physician (15). Because patient preference is an important factor in choosing among possible treatments, we also assessed patient satisfaction using a similar scale. Overall, about 90% of patients had a good or excellent cosmetic result after two years of follow-up. Consistent with what others have reported (19), we saw moderate to substantial agreement between physician and patient assessment of cosmetic outcome. In contrast to what has been reported by others (32, 38), no significant change in cosmetic outcome over time was seen; although some individual patients did have changes in cosmesis. This may be due to the smaller volume of irradiated tissue remaining after the completion of the surgical procedure.

An important aspect of APBI is patient convenience, comfort, and acceptance of the outcome. In our study, nearly all patients reported that they would choose IORT again, and over 80% of patients reported being totally satisfied with the process.

No wound healing complications were seen following IORT. Delivering radiation prior to tumor excision results in a relatively small volume of treated breast tissue that remains in situ. While this may result in better cosmesis, it may also result in an increased risk of local recurrence, an issue we continue to study and which will be reported separately.

There are several advantages to our technique of delivering IORT. We are able to directly visualize the target volume, avoid excessive irradiation of normal tissues, and minimize irradiation of healthy lung. The lack of perturbation of the tumor bed minimizes the risk of tumor dissemination along tissue planes, enabling us to use a small margin, reminiscent of pre-operative vs. post-operative radiotherapy of sarcomas. We can take advantage of a theoretical radiobiological advantage of a short treatment course (39) and deliver radiation on the day of surgery, avoiding the need for 4 to 6 weeks of post-operative radiation. A technique with such good patient acceptance and cosmetic outcomes may encourage more women to undergo BCT and to complete all recommended therapy if it proves as efficacious as standard therapy.

There are several disadvantages associated with our approach. First, because we perform IORT at the time of surgery some women will need additional surgical therapy and/or will not be appropriate candidates for APBI and/or BCT. Women were told of this possibility as part of the consent process. In all, seven women underwent a mastectomy and eleven received standard WBRT with the IORT serving as the boost, thus shortening the time required for external beam radiation by 5–8 days. Women who required a re-resection typically underwent this procedure within 3–4 weeks of IORT, before radiation fibrosis had a chance to make the procedure more technically difficult.

We have reported here the cosmetic results of our trial of IORT of in situ tumors for women with early stage breast cancer. Regarding the primary endpoint of our trial, cosmetic outcome was not inferior in our study to that expected based on the RTOG 95-17 trial. We eagerly await the results of the large randomized trial of APBI vs. BCT. While this will shed light on the role of APBI, it is not designed to determine an optimal treatment method. Instead, it is likely that each of the techniques will be used based on institutional resources and clinical expertise. Targeting the tumor in situ results in: immediate completion of BCT for the majority of women and acceptable cosmetic results.

Acknowledgments

Supported by UNC/Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center, Sisko, Rodney and Ruth James Foundation. RJK has been designated a B. Leonard Holman Pathway Fellow by the American Board of Radiology and is supported by a Radiological Society of North America Research Resident Grant.

Footnotes

Meeting presentation: ASCO 2008 Annual Meeting

Conflicts of Interest: The authors report no potential conflicts of interest related to this manuscript.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Morrow M, White J, Moughan J, et al. Factors predicting the use of breast-conserving therapy in stage I and II breast carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:2254–2262. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.8.2254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nattinger AB, Hoffmann RG, Kneusel RT, et al. Relation between appropriateness of primary therapy for early-stage breast carcinoma and increased use of breast-conserving surgery. Lancet. 2000;356:1148–1153. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02757-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McGinnis LS, Menck HR, Eyre HJ, et al. National Cancer Data Base survey of breast cancer management for patients from low income zip codes. Cancer. 2000;88:933–945. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mandelblatt JS, Hadley J, Kerner JF, et al. Patterns of breast carcinoma treatment in older women: patient preference and clinical and physical influences. Cancer. 2000;89:561–573. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nattinger AB, Kneusel RT, Hoffmann RG, et al. Relationship of distance from a radiotherapy facility and initial breast cancer treatment. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2001;93:1344–1346. doi: 10.1093/jnci/93.17.1344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Athas WF, Adams-Cameron M, Hunt WC, et al. Travel distance to radiation therapy and receipt of radiotherapy following breast-conserving surgery. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92:269–271. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.3.269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Clarke M, Collins R, Darby S, et al. Effects of radiotherapy and of differences in the extent of surgery for early breast cancer on local recurrence and 15-year survival: an overview of the randomised trials. Lancet. 2005;366:2087–2106. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67887-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Veronesi U, Orecchia R, Luini A, et al. Full-dose intraoperative radiotherapy with electrons during breast-conserving surgery: experience with 590 cases. Ann Surg. 2005;242:101–106. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000167927.82353.bc. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Intra M, Gatti G, Luini A, et al. Surgical technique of intraoperative radiotherapy in conservative treatment of limited-stage breast cancer. Arch Surg. 2002;137:737–740. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.137.6.737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vaidya JS, Baum M, Tobias JS, et al. Targeted intra-operative radiotherapy (Targit): an innovative method of treatment for early breast cancer. Ann Oncol. 2001;12:1075–1080. doi: 10.1023/a:1011609401132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sacchini V, Beal K, Goldberg J, et al. Study of quadrant high-dose intraoperative radiation therapy for early-stage breast cancer. Br J Surg. 2008;95:1105–1110. doi: 10.1002/bjs.6208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ollila DW, Klauber-Demore N, Tesche LJ, et al. Feasibility of Breast Preserving Therapy with Single Fraction In Situ Radiotherapy Delivered Intraoperatively. Ann Surg Oncol. 2006 doi: 10.1245/s10434-006-9154-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stitzenberg KB, Klauber-Demore N, Chang XS, et al. In vivo intraoperative radiotherapy: a novel approach to radiotherapy for early stage breast cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2007;14:1515–1516. doi: 10.1245/s10434-006-9152-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Reitsamer R, Peintinger F, Kopp M, et al. Local Recurrence Rates in Breast Cancer Patients Treated with Intraoperative Electron-Boost Radiotherapy Versus Postoperative External-Beam Electron-Boost Irradiation. Strahlenther Onkol. 2004;180:38–44. doi: 10.1007/s00066-004-1190-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wazer DE, DiPetrillo T, Schmidt-Ullrich R, et al. Factors influencing cosmetic outcome and complication risk after conservative surgery and radiotherapy for early-stage breast carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 1992;10:356–363. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1992.10.3.356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Trotti A, Byhardt R, Stetz J, et al. Common toxicity criteria: version 2.0. an improved reference for grading the acute effects of cancer treatment: impact on radiotherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2000;47:13–47. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(99)00559-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kuske RR, Winter K, Arthur DW, et al. Phase II trial of brachytherapy alone after lumpectomy for select breast cancer: toxicity analysis of RTOG 95–17. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2006;65:45–51. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2005.11.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kraus-Tiefenbacher U, Bauer L, Scheda A, et al. Long-term toxicity of an intraoperative radiotherapy boost using low energy X-rays during breast-conserving surgery. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2006;66:377–381. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2006.05.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vaidya JS, Wilson AJ, Houghton J, et al. Cosmetic outcome after targeted intraoperative radiotherapy (TARGIT) for early breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2003;82:1039. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Beal K, McCormick B, Zelefsky MJ, et al. Single-Fraction Intraoperative Radiotherapy for Breast Cancer: Early Cosmetic Results. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2007;69:19–24. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2007.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dobelbower RR, Merrick HW, Eltaki A, et al. Intraoperative electron beam therapy and external photon beam therapy with lumpectomy as primary treatment for early breast cancer. Ann Radiol (Paris) 1989;32:497–501. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Merrick HW, 3rd, Battle JA, Padgett BJ, et al. IORT for early breast cancer: a report on long-term results. Front Radiat Ther Oncol. 1997;31:126–130. doi: 10.1159/000061177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gatzemeier W, Orecchia R, Gatti G, et al. Intraoperative radiotherapy (IORT) in treatment of breast carcinoma--a new therapeutic alternative within the scope of breast-saving therapy? Current status and future prospects. Report of experiences from the European Institute of Oncology (EIO), Mailand. Strahlenther Onkol. 2001;177:330–337. doi: 10.1007/pl00002415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fagundes MA, Fagundes HM, Brito CS, et al. Breast-conserving surgery and definitive radiation: a comparison between quadrantectomy and local excision with special focus on local-regional control and cosmesis. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1993;27:553–560. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(93)90379-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wazer DE, Kaufman S, Cuttino L, et al. Accelerated partial breast irradiation: an analysis of variables associated with late toxicity and long-term cosmetic outcome after high-dose-rate interstitial brachytherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2006;64:489–495. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2005.06.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Arthur DW, Koo D, Zwicker RD, et al. Partial breast brachytherapy after lumpectomy: low-dose-rate and high-dose-rate experience. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2003;56:681–689. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(03)00120-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Blichert-Toft M, Rose C, Andersen JA, et al. Danish randomized trial comparing breast conservation therapy with mastectomy: six years of life-table analysis. Danish Breast Cancer Cooperative Group. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 1992:19–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Romestaing P, Lehingue Y, Carrie C, et al. Role of a 10-Gy boost in the conservative treatment of early breast cancer: results of a randomized clinical trial in Lyon, France. J Clin Oncol. 1997;15:963–968. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1997.15.3.963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Curran D, van Dongen JP, Aaronson NK, et al. Quality of life of early-stage breast cancer patients treated with radical mastectomy or breast-conserving procedures: results of EORTC Trial 10801. The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC), Breast Cancer Co-operative Group (BCCG) Eur J Cancer. 1998;34:307–314. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(97)00312-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vicini FA, Chen P, Wallace M, et al. Interim Cosmetic Results and Toxicity Using 3D Conformal External Beam Radiotherapy to Deliver Accelerated Partial Breast Irradiation in Patients With Early-Stage Breast Cancer Treated With Breast-Conserving Therapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2007;69:1124–1130. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2007.04.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Formenti SC, Truong MT, Goldberg JD, et al. Prone accelerated partial breast irradiation after breast-conserving surgery: preliminary clinical results and dose-volume histogram analysis. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2004;60:493–504. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2004.04.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chen PY, Vicini FA, Benitez P, et al. Long-term cosmetic results and toxicity after accelerated partial-breast irradiation: a method of radiation delivery by interstitial brachytherapy for the treatment of early-stage breast carcinoma. Cancer. 2006;106:991–999. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Baglan KL, Martinez AA, Frazier RC, et al. The use of high-dose-rate brachytherapy alone after lumpectomy in patients with early-stage breast cancer treated with breast-conserving therapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2001;50:1003–1011. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(01)01547-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wazer DE, Berle L, Graham R, et al. Preliminary results of a phase I/II study of HDR brachytherapy alone for T1/T2 breast cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2002;53:889–897. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(02)02824-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Poti Z, Nemeskeri C, Fekeshazy A, et al. Partial breast irradiation with interstitial 60CO brachytherapy results in frequent grade 3 or 4 toxicity. Evidence based on a 12-year follow-up of 70 patients. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2004;58:1022–1033. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2003.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dragun AE, Harper JL, Jenrette JM, et al. Predictors of cosmetic outcome following MammoSite breast brachytherapy: a single-institution experience of 100 patients with two years of follow-up. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2007;68:354–358. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2006.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chao KK, Vicini FA, Wallace M, et al. Analysis of Treatment Efficacy, Cosmesis, and Toxicity Using the MammoSite Breast Brachytherapy Catheter to Deliver Accelerated Partial-Breast Irradiation: The William Beaumont Hospital Experience. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2007;69:32–40. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2007.02.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Benitez PR, Chen PY, Vicini FA, et al. Partial breast irradiation in breast conserving therapy by way of intersitial brachytherapy. Am J Surg. 2004;188:355–364. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2004.06.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Herskind C, Steil V, Kraus-Tiefenbacher U, et al. Radiobiological aspects of intraoperative radiotherapy (IORT) with isotropic low-energy X rays for early-stage breast cancer. Radiat Res. 2005;163:208–215. doi: 10.1667/rr3292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]