Abstract

Fat tissue, frequently the largest organ in humans, is at the nexus of mechanisms involved in longevity and age-related metabolic dysfunction. Fat distribution and function change dramatically throughout life. Obesity is associated with accelerated onset of diseases common in old age, while fat ablation and certain mutations affecting fat increase life span. Fat cells turn over throughout the life span. Fat cell progenitors, preadipocytes, are abundant, closely related to macrophages, and dysdifferentiate in old age, switching into a pro-inflammatory, tissue-remodeling, senescent-like state. Other mesenchymal progenitors also can acquire a pro-inflammatory, adipocyte-like phenotype with aging. We propose a hypothetical model in which cellular stress and preadipocyte overutilization with aging induce cellular senescence, leading to impaired adipogenesis, failure to sequester lipotoxic fatty acids, inflammatory cytokine and chemokine generation, and innate and adaptive immune response activation. These pro-inflammatory processes may amplify each other and have systemic consequences. This model is consistent with recent concepts about cellular senescence as a stress-responsive, adaptive phenotype that develops through multiple stages, including major metabolic and secretory readjustments, which can spread from cell to cell and can occur at any point during life. Senescence could be an alternative cell fate that develops in response to injury or metabolic dysfunction and might occur in nondividing as well as dividing cells. Consistent with this, a senescent-like state can develop in preadipocytes and fat cells from young obese individuals. Senescent, pro-inflammatory cells in fat could have profound clinical consequences because of the large size of the fat organ and its central metabolic role.

Keywords: aging, cellular senescence, diabetes, fat tissue, inflammation, obesity, preadipocyte

Introduction

Fat tissue is at the nexus of mechanisms and pathways involved in longevity, genesis of age-related diseases, inflammation, and metabolic dysfunction. Major changes in fat distribution and function occur throughout life. In old age, these changes are associated with diabetes, hypertension, cancers, cognitive dysfunction, and atherosclerosis leading to heart attacks and strokes (Guo et al., 1999; Lutz et al., 2008). Excess or dysfunctional fat tissue appears to accelerate onset of multiple age-related diseases, while interventions that delay or limit fat tissue turnover, redistribution, or dysfunction in experimental animals are associated with enhanced healthspan and maximum life span. For example, obesity leads to reduced life span and clinical consequences similar to those common in aging (Ahima, 2009). Conversely, life span is extended: (i) by caloric restriction [which preferentially leads to reduced visceral fat (Barzilai & Gupta, 1999; Masoro, 2006)]; (ii) in fat cell insulin receptor (FIRKO), insulin receptor substrate-1 (IRS-1), and S6 kinase-1 knockout mice [each of which has limited fat development (Bluher et al., 2003; Um et al., 2004; Selman et al., 2008, 2009)]; (iii) in growth hormone receptor knockout (GHRKO) mice [which have reduced IGF-1, delayed increase in the ratio of visceral to subcutaneous fat, and most likely reduced fat cell progenitor turnover (Berryman et al., 2008)]; (iv) with rapamycin treatment [which limits fat tissue development (Chang et al., 2009; Harrison et al., 2009)]; and (v) after surgical removal of visceral fat (Muzumdar et al., 2008). One reason why age-related changes in fat tissue function may entail such profound systemic consequences is that fat is frequently the largest organ in humans. Indeed, it constitutes over half the body in an alarmingly high and increasing number of people [e.g., in women, who have a higher percent body fat than men, with a body mass index (BMI) over 35 kg m−2].

Exciting new data are beginning to point to the cell biological and molecular mechanisms that determine how aging impacts fat tissue function and how this, in turn, leads to age-related disease. Lessons from what happens in obesity are especially illuminating. In particular, inflammatory processes linked to cellular senescence in fat tissue could be pivotal. Fat tissue is important in host defense, immunity, injury responses, and production of inflammatory cytokines and chemokines. It is rich in progenitors that can produce pro-inflammatory factors and that are susceptible to cellular senescence. We suggest the possibility that cellular injury responses, activation of innate immunity, accumulation of dysfunctional, dysdifferentiated progenitors [mesenchymal macrophage- and adipocyte-like default (MAD) cells (Kirkland et al., 2002)], and cellular senescence may all be within a spectrum of activated pro-inflammatory fates comprising an alternative differentiation state. Accumulation of senescent cells in fat with aging could be caused by increased generation of these cells owing to a combination of replicative, cytokine-induced, and metabolic stresses as well as reduced removal of senescent cells because of failure of immune cells from older individuals to respond efficiently to chemokines released by senescent cells. In cancer, these chemokines cause the immune system to hone in on senescent cells and the cancer cells around them, resulting in destruction of the cancer cells and removal of the senescent cells (Xue et al., 2007). Furthermore, there are indications that a senescent-like state can occur in nonreplicating, differentiated cells in fat tissue. If true, these points would challenge existing concepts about cellular senescence. To begin to address these hypotheses, relevant findings about aging, obesity, cellular senescence, and inflammation in fat tissue will be considered.

Fat tissue

Fat tissue function

In addition to storing energy, fat is important in immune and endocrine function, thermoregulation, mechanical protection, and tissue regeneration. The main role of fat is to store calorically dense fatty acids. These highly reactive, cytotoxic molecules are sequestered as less reactive triglyceride within fat droplets, protecting against systemic lipotoxicity [cytotoxicity owing to fatty acids and lipid metabolites; (Tchkonia et al., 2006a)]. To accommodate wide swings in nutrient availability, fat tissue is capable of rapid, extensive changes in size, especially subcutaneous fat, which is not subject to the anatomic constraints to growth that limit visceral fat. Growth is accomplished through changes in fat cell size or number that vary in magnitude among fat depots.

Adipose tissue is located strategically beneath the skin and around vital organs, where it protects against infection and trauma. Bacterial and fungal infections of fat are uncommon, and metastases are unusual, likely related to the innate and adaptive immune elements in fat tissue, as well as potentially high local fatty acid concentrations that are lethal to pathogens and nonadipose cell types (Tchkonia et al., 2006a). Dysregulated activation of fat tissue immune responses may predispose individuals to the metabolic dysfunction common in both obesity and aging.

Fat tissue produces hormones, including IL-6, angiotensin II, leptin, adiponectin, and IGF-1 (in response to GH), and activates hormones, for example glucocorticoids and sex steroids. It releases paracrine factors in an endocrine-like fashion by developing in target organs and releasing factors that impact their function. For example, fat in muscle regulates muscle glucose homeostasis and insulin responses (Abel et al., 2001). In addition to regional variation in fat tissue endocrine and paracrine factor production, differences in venous drainage contribute to the distinct metabolic effects of different fat depots. For example, omental and some regions of mesenteric fat drains directly into the liver through the portal vein.

Adipose tissue is involved in thermoregulation, both by preventing heat loss through its insulating effects and by generating heat in brown fat. Fat affords mechanical protection by developing at sites of mechanical stress or pressure. It forms a buffer that dissipates pressure over bony prominences, preventing skin breakdown. Fat is rich in mesenchymal progenitors that can give rise to multiple cell types, including fat cells (Cartwright et al., 2007). The multipotent progenitors resident in fat may promote tissue regeneration during wound healing.

Aging

Fat tissue mass increases through middle age and declines in old age (Visser et al., 2003; Raguso et al., 2006). Fat is redistributed among different fat depots over time, especially during and after middle age, when fat redistributes from subcutaneous to intra-abdominal visceral depots (Meunier et al., 1971; Kotani et al., 1994; Matsuzawa et al., 1995; Kyle et al., 2001; Raguso et al., 2006; Slawik & Vidal-Puig, 2006; Cartwright et al., 2007; Rabkin, 2007; Kuk et al., 2009). Consistent with this, the percent of meal fat stored in subcutaneous depots is lower in older than younger men and women, and abdominal circumference increases by 4.0 cm every 9 years in adult women (Hughes et al., 2004; Koutsari et al., 2009). In old age, fat is redistributed outside fat depots, accumulating in bone marrow, muscle, liver, and other ectopic sites. As in aging, genetic and acquired lipodystrophic syndromes are associated with fat tissue dysfunction, subcutaneous fat loss, increased visceral and ectopic fat, and metabolic syndrome [glucose intolerance, insulin resistance, central obesity, dyslipidemia, and hypertension (Garg & Agarwal, 2009)]. Metabolic syndrome in the elderly, in turn, is associated with increased inflammation, cardiovascular and all-cause mortality, cognitive impairment, and accelerated functional decline (Koster et al. 2010; Morley, 2004).

As in humans, mice and rats have fat redistribution and ectopic fat deposition with aging. This is delayed in mouse models with increased maximum life span because of growth hormone and/or insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) deficiency. While short-term growth hormone exposure decreases visceral fat by enhancing lipolysis, in animals with lifelong excess growth hormone, fat redistribution begins earlier, advances faster, and is associated with decreased life span (Berryman et al., 2004, 2009; Palmer et al., 2009). Removal of visceral fat enhances insulin sensitivity and extends maximum life span in rats (Barzilai et al., 1999; Muzumdar et al., 2008; Huffman & Barzilai, 2009). Conversely, decreased ability of subcutaneous adipocytes to store lipid, as occurs with aging, may contribute to metabolic complications by causing systemic lipotoxicity (Lelliott & Vidal-Puig, 2004; Carley & Severson, 2005; Unger, 2005; Uranga et al., 2005; Tchkonia et al., 2006a; Kuk et al., 2009). Thus, fat redistribution with aging occurs across species and is associated with age-related diseases, lipotoxicity, and reduced longevity, while retention of a high ratio of functioning subcutaneous to visceral fat is associated with enhanced longevity.

Substantial changes in fat tissue metabolic function occur during aging, with declines in insulin, lipolytic, and fatty acid responsiveness (Bertrand et al., 1980; Yu et al., 1982; Kirkland & Dax, 1984; Yki-Jarvinen et al., 1986; Silver et al., 1993; Gregerman, 1994; Kirkland & Dobson, 1997; Kirkland et al., 2002; Das et al., 2004; Tchkonia et al., 2006a). Together with preadipocyte dysfunction, impairments in ability to accumulate or mobilize lipid with aging reduce the dynamic range over which fat cells can store or release energy or respond to excess systemic lipotoxic fatty acids.

Fat tissue cytokines, including tumor necrosis factor-α (TNFα) and interleukin (IL-6), can increase with aging (Morin et al., 1997; Starr et al., 2009). Increased adiponectin, a cytokine that exists in several isoforms and that originates from fat as well as other tissues, has been associated with reduced risk of metabolic syndrome in the elderly (Lim et al. 2010; Stenholm et al., 2009). It is higher in centenarians and their offspring than the general population (Atzmon et al., 2008). However, increased adiponectin is associated with increased mortality in the elderly, perhaps related to production by the vascular system in atherosclerosis (Rizza et al. 2010; Poehls et al., 2009). More needs to be done to understand whether there are age-related changes in adiponectin production by cells in fat tissue and what the consequences are.

Immune effector abundance appears to change with aging in a fat depot-dependent manner. Macrophage abundance increases in subcutaneous fat with aging in mice (Jerschow et al., 2007). However, macrophage numbers that are already high in intra-abdominal fat of young mice do not increase further with aging (Harris et al., 1999; Jerschow et al., 2007). Little is known about the impact of aging on fat tissue lymphocyte, mast cell, or macrophage abundance in humans.

Brown fat generates heat through uncoupled mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation. Aging is associated with loss of brown fat as well as brown fat preadipocyte dysfunction in rodents (Gabaldon et al., 1998; McDonald & Horwitz, 1999; Gabaldon et al., 2003). This is delayed by caloric restriction (Valle et al., 2008). Brown fat also decreases with aging in humans, in whom it is interspersed with white fat in the neck and upper chest (Cypess et al., 2009). Decreased brown fat may contribute to thermal dysregulation and energy imbalance.

Obesity

Obesity has been likened to an accelerated form of fat tissue aging (Ahima, 2009; Minamino et al., 2009; Tchkonia et al., 2009). Obesity causes premature death from many of the same causes as those common in elderly lean individuals: diabetes, heart attacks, strokes, cancer, and dementia (Bjorntorp, 1990; Denke et al., 1993, 1994; Colditz et al., 1995; Lean, 2000). Obesity and aging are both associated with chronic, low-grade inflammation and insulin resistance, increased local and circulating proinflammatory, chemotactic, and procoagulant proteins, and ectopic lipid deposition with lipotoxicity (Hotamisligil & Spiegelman, 1994; Samad et al., 1996, 1997; Vgontzas et al., 1997; Fried et al., 1998; Loffreda et al., 1998; Samad et al., 1998; Ferri et al., 1999; Visser et al., 1999; Perreault & Marette, 2001; De Pergola & Pannacciulli, 2002; Weyer et al., 2002; Sartipy & Loskutoff, 2003; Takahashi et al., 2003; Weisberg et al., 2003; Xu et al., 2003; Curat et al., 2004; Tchkonia et al., 2006a). This is especially true in massive or visceral obesity. As in aging, fat tissue adipogenic transcription factor expression is decreased in obesity, and inflammatory mediators, including TNFα and IL-6, are increased (Nadler et al., 2000; Xu et al., 2002; Weisberg et al., 2003; Xu et al., 2003; Nair et al., 2005; Jerschow et al., 2007). Much more is known about fat tissue dysfunction in obesity than aging. Analysis of processes causing fat tissue dysfunction in obesity could point to mechanisms contributing to metabolic dysfunction with aging and even the aging process itself.

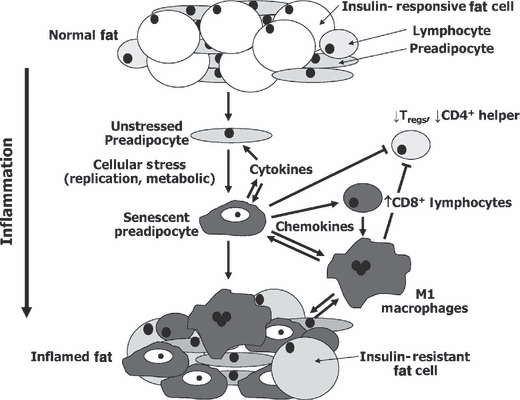

Events leading to fat tissue inflammation in obesity have been investigated by examining effects of high fat feeding in rodents (Fig. 1). These diets induce fat tissue inflammatory cytokine, chemokine, and extracellular matrix (ECM)-modifying protein production within days to weeks (Xu et al., 2003; Suganami et al., 2005; Nishimura et al., 2009). This is associated with shifts in T-lymphocyte subsets, rather than absolute numbers of T lymphocytes (Feuerer et al., 2009; Nishimura et al., 2009). High fat feeding results in an increased proportion of CD8+ effector T lymphocytes, with a progressive increase in cells releasing pro-inflammatory TH1 cytokines, relative to CD4+ helper cells and T regulatory cells [Tregs; (Feuerer et al., 2009; Nishimura et al., 2009; Winer et al., 2009)]. This also occurs in humans: CD8A is higher and Tregs are reduced in fat tissue from obese compared to lean humans (Feuerer et al., 2009; Nishimura et al., 2009). Fat tissue from obese mice induces CD8+ lymphocyte activation and proliferation in coculture (Nishimura et al., 2009), suggesting chemokines produced by fat could be upstream of changes in T-lymphocyte subsets. Fat also becomes infiltrated by mast cells as obesity develops in mice and humans (Liu et al., 2009). Mast cells contribute to production of IL-6, interferon-γ, and metabolic complications of obesity, including insulin resistance and fatty liver.

Fig. 1.

Hypothetical model of the chain of events culminating in fat tissue inflammation in obesity. Preadipocytes and fat tissue endothelial cells may acquire an activated, pro-inflammatory, senescent-like phenotype in response to repeated replication, fatty acids, toxic metabolites, chronically high IGF-1, glucose, or other stimuli (gray = inflamed). Inflammatory cytokines could spread this activated secretory phenotype from cell to cell and block full differentiation of preadipocytes into insulin-responsive fat cells, amplifying the process. Chemokines, cytokines, and ECM modifiers produced by pro-inflammatory cells might activate adaptive immune responses. Shifts from anti- to proinflammatory T-lymphocyte subsets and mast cell infiltration owing to cytokine and lymphokine production, toxic metabolites (including fatty acids and reactive oxygen species), and cytokines released by inflamed preadipocytes and endothelial cells may combine to promote M1 macrophage activation. The inflammatory cytokines could induce systemic effects, further impede adipogenesis, and promote fat cell lipolysis, releasing fatty acids that aggravate the fat tissue pro-inflammatory state and cause systemic lipotoxicity. Similar processes could be involved in age-related fat tissue dysregulation and metabolic dysfunction. Some of these processes appear to vary in extent among fat depots in obesity (Feuerer et al., 2009; Nishimura et al., 2009; Winer et al., 2009) as well as aging (Cartwright et al., 2010).

Following shifts in T-lymphocyte subsets and mast cell accumulation during development of obesity, fat becomes infiltrated by classically activated M1 macrophages (Weisberg et al., 2003; Xu et al., 2003; Kintscher et al., 2008; Liu et al., 2009; Lumeng et al., 2009; Nishimura et al., 2009). This is likely due to chemokines, including interferon-γ [from T lymphocytes, and mast cells (Kintscher et al., 2008; Liu et al., 2009; Sebastian et al., 2009; Winer et al., 2009)], monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 [MCP-1; from preadipocytes and other cell types (Gustafson et al., 2009)], RANTES [from preadipocytes, endothelial cells, and other cell types (Feuerer et al., 2009)], and RARRES2 [from preadipocytes (Kralisch et al., 2009)]. Little MCP-1 or RANTES is produced by fat cells themselves (Fain et al. 2009).

The stromal vascular fraction of adipose tissue (comprising preadipocytes, endothelial cells, immune cells, and other cell types) may be the main source of inflammatory cytokines and chemokines produced by fat (Fain et al. 2009; Wu et al., 2007; Gustafson et al., 2009). Macrophage infiltration owing to a high fat diet depends more on cells in the stromal vascular fraction of fat tissue than fat cells (Weisberg et al., 2003). Once activated, macrophages release yet more inflammatory cytokines that lead to further production of MCP-1 and other chemokines, inducing further macrophage infiltration and inflammation in a vicious cycle. A central question that has not been fully answered is: what cell types, metabolites, and/or antigens are upstream of the shifts in T-lymphocyte subsets and mast cell accumulation that precede macrophage infiltration?

Fat tissue distribution in obesity

Different fat depots make distinct contributions to the pro-inflammatory and clinical consequences of obesity and, potentially, aging. Visceral fat enlargement is more strongly associated with ectopic fat deposition, lipotoxicity, and metabolic disease than generalized obesity, especially in old age (Carr et al., 2004; Tchkonia et al., 2006a; Wannamethee et al., 2007; Gustafson et al., 2009; Thomou et al., 2010). Even otherwise lean individuals with relatively more intra- than extra-abdominal fat are at increased risk for diabetes and mortality (Pischon et al., 2008). Removing intra-abdominal fat reduces insulin resistance more profoundly than removing subcutaneous fat from rodents (Barzilai et al., 1999; Weber et al., 2000; Gabriely et al., 2002; Huffman & Barzilai, 2009). Removing large amounts of subcutaneous fat from humans does not improve insulin sensitivity (Klein et al., 2004). Subcutaneous fat expansion in obesity may actually be protective (Kim et al., 2007; Tran et al., 2008). Cytokine and chemokine production by different fat depots varies, with visceral fat being more pro-inflammatory (Samaras et al. 2010; Einstein et al., 2005; Tchkonia et al., 2006a; Huffman & Barzilai, 2009; Starr et al., 2009; Thomou et al., 2010). IL-6 levels are higher in visceral than subcutaneous fat in mice, and nutrient excess induces more visceral fat expression of TNFα and plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (PAI-1), a hemostatic factor associated with atherosclerosis [Einstein et al., 2005; Starr et al., 2009]).

Is obesity accelerated fat tissue aging?

While obesity is associated with accelerated development of diseases common in old age, mechanisms of fat tissue dysfunction in obesity differ from aging in important ways. Fat cell size is increased in many depots in obesity (Fried & Kral, 1987) and is associated with fat cell death and macrophage infiltration around the dying cells (Cinti et al., 2005). In aging, unlike obesity, this may not contribute substantially to inflammation, because fat cells are generally smaller in old than middle age (Bertrand et al., 1978, 1980). Whole fat tissue gene expression profiles differ in obesity from changes during development (Miard & Picard, 2008). Fat tissue transcripts that change during development (four compared with 12 month old mice) did not correlate well with transcripts affected by obesity (4- month-old obese compared to lean mice). This could be related to differences between changes in fat tissue cellular composition during development from those in obesity. For example, macrophage infiltration in visceral fat from young obese individuals is more impressive than lean old individuals (Weisberg et al., 2003; Xu et al., 2003; Wu et al., 2007).

Whether the basis of fat tissue dysfunction in obesity and aging is the same is more than academic. Clinical consequences of obesity are increasingly close to being amenable to novel interventions based on targeting inflammation and fat tissue cellular composition. For example, antibody-mediated CD8+ depletion reduces high fat diet-induced TNFα, IL-6, and M1 macrophage abundance and improves insulin responsiveness in mice (Nishimura et al., 2009). CD3 antibody restores Tregs, decreases pro-inflammatory M1 relative to anti-inflammatory M2 macrophages, increases antidiabetic IL-10, and reverses insulin resistance for over 4 months despite a high fat diet (Winer et al., 2009). Injection of an IL-2 antibody increases Tregs and anti-inflammatory IL10 in abdominal fat and decreases blood glucose in mice on a high fat diet (Feuerer et al., 2009). Transplantation of anti-inflammatory TH2 cells into lymphocyte-deficient mice reverses insulin resistance and MCP-1 owing to a high-fat diet (Winer et al., 2009). Reducing mast cells by genetic manipulation or pharmacologic stabilization with disodium chromoglycate reduces hepatic steatosis, circulating inflammatory cytokines and chemokines, angiogenesis, and insulin resistance in obese mice (Liu et al., 2009). Blocking TLR4 in cells originating from bone marrow or ablating CD11c+ macrophages reduces insulin resistance in obese mice (Patsouris et al., 2008; Saberi et al., 2009). To the extent that age-related fat tissue dysfunction is similar to obesity, analogous interventions might prevent clinical consequences of age-related fat tissue dysfunction.

Preadipocytes

Preadipocyte function

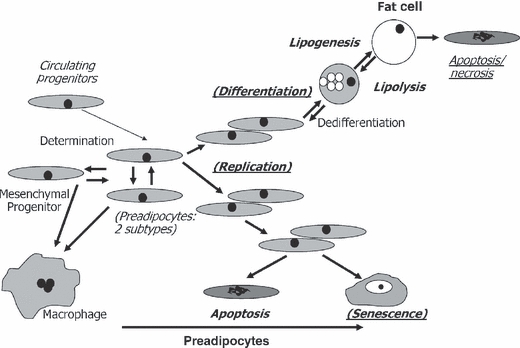

Preadipocytes comprise 15–50% of cells in fat, one of the largest progenitor pools in the body (Fig. 2). Preadipocytes replicate in response to mitogens, including IGF-1 (Boney et al., 2001; Sekimoto et al., 2005). They are mainly resident in fat depots, although a small pool of circulating fat cell progenitors exists (Crossno et al., 2006). Preadipocytes, in turn, may arise from or be the same as the multipotent mesenchymal progenitors (also referred to as adipose tissue stem cells) that tend to be aligned along fat tissue blood vessels in a pericyte-like fashion (Tang et al., 2008). Preadipocytes resident in different fat depots are distinct cell subtypes that differ in developmental gene expression and capacities for replication, differentiation, and apoptosis (Yamamoto et al. 2010; Kirkland et al., 1990; Tchkonia et al., 2001, 2002, 2006b, 2007b). These differences persist for at least 40 population doublings in strains made by expressing telomerase in single human preadipocytes from different fat depots. Regional differences in preadipocyte clonal capacities for replication and adipogenesis predict subsequent fat tissue growth (Wang et al., 1989).

Fig. 2.

Impact of aging, obesity, anatomic origin, and serial passage on cell dynamic mechanisms of fat tissue turnover. Up to 50% of cells in fat tissue are committed preadipocytes that arise from multipotent, slowly replicating mesenchymal progenitor cells and possibly circulating progenitors (Hong et al., 2005; Crossno et al., 2006). Preadipocyte numbers are maintained by replication. Preadipocytes can reversibly switch into a slowly replicating subtype, can become macrophage-like, and may be able to progress up or down the adipocytic lineage (Cousin et al., 1999; Charriere et al., 2003; Tchkonia et al., 2005; Gustafson et al., 2009). Preadipocytes are depleted by differentiation into fat cells, apoptosis, necrosis, and cellular senescence. Enlargement of fat cells (lipid accumulation) and maintenance of insulin responsiveness are tied to processes initiated during differentiation, including adipogenic transcription factor expression. Fat cells, especially large fat cells, can be removed by a process with features of both apoptosis and necrosis and that can induce inflammation. The balance among these cell dynamic properties determines preadipocyte and fat cell numbers. Cell dynamic processes that vary with aging are in bold, obesity are underlined, anatomic origin in Italics, and serial passage in parentheses. These differences persist for at least 40 population doublings in cloned preadipocytes in the case of anatomic origin, 16 in aging, and 8 in obesity.

Preadipocyte metabolic and secretory profiles are distinct from differentiated fat cells and vary among fat depots (Kirkland et al., 1994, 2003; Tchkonia et al., 2007b). Preadipocytes express toll-like receptors and have full innate immune response capability (Lin et al., 2000; Chung et al., 2006; Vitseva et al., 2008). Preadipocytes with activated immune responses likely make a larger contribution than macrophages to age-related fat tissue dysfunction because of their numbers (Xu et al., 2002; Gustafson et al., 2009; Mack et al., 2009). Gene expression profiles of preadipocytes are closer to macrophages than fat cells (Charriere et al., 2003). TNFα and hypoxia induce preadipocytes to release cytokines and chemokines that activate endothelial cells and promote macrophage infiltration (Mack et al., 2009). Treatment of undifferentiated human preadipocytes with TNFα or lipopolysaccharide (LPS) induces CD68, MIP1α, IL-1β, and GM-CSF expression (Gustafson et al., 2009). Activated preadipocytes can even acquire a macrophage-like morphological phenotype (Cousin et al., 1999; Gustafson et al., 2009). Their plasticity and capacity to mount innate immune responses enable preadipocytes to participate in wound repair and defense against infection but also predispose them to contribute to fat tissue inflammation and dysfunction.

The main role of preadipocytes is to give rise to new fat cells. Following initiation of differentiation through signaling pathways activated by fatty acids, IGF-1, glucocorticoids, and other stimuli, a cascade of transcription factors underlies acquisition and maintenance of the fat cell phenotype (Lowell, 1999; Rosen, 2005). The key ‘bottleneck’ in this process is at the level of the adipogenic transcription factors, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ (PPARγ) and CCAAT/enhancer binding protein-α [C/EBPα; (Lin & Lane, 1994; Hu et al., 1995; Wu et al., 1995; Yeh et al., 1995; Wu et al., 1999; Farmer, 2005)]. PPARγ binds a ligand [e.g., endogenous or dietary lipids or thiazolidinedione (TZD) antidiabetic drugs], heterodimerizes with a ligand-bound retinoid receptor and then induces C/EBPα (Wu et al., 1996; Hamm et al., 2001). C/EBPα, in turn, further increases PPARγ expression (Clarke et al., 1997; Burgess-Beusse et al., 1999). C/EBPα and PPARγ cooperate in regulating downstream adipogenic genes (Hollenberg et al., 1997; El Jack et al., 1999). Sustained activity of both is necessary for development of fully functional, insulin-responsive fat cells and for downregulating the pro-inflammatory proclivities of preadipocytes.

Aging and preadipocyte function

Extensive changes in preadipocyte function occur with aging [Fig. 2; (Djian et al., 1983; Wang et al., 1989; Kirkland et al., 1990, 1993, 1994, 1997; Kirkland & Dobson, 1997; Kirkland & Hollenberg, 1998; Caserta et al., 2001; Karagiannides et al., 2001; Kirkland et al., 2002; Karagiannides et al., 2006b; Guo et al., 2007; Tchkonia et al., 2007a; Cartwright et al., 2010)]. These include declines in preadipocyte replication (Djian et al., 1983; Kirkland et al., 1990; Kirkland & Hollenberg, 1998; Schipper et al., 2008), decreased adipogenesis (Kirkland et al., 1990, 1993; Karagiannides et al., 2001, 2006b), increased susceptibility to lipotoxicity (Guo et al., 2007), and increased pro-inflammatory cytokine, chemokine, ECM-modifying protease, and stress response element expression (Tchkonia et al., 2007a; Cartwright et al., 2010). These changes progress at different rates and to different extents in preadipocytes from different fat depots (Djian et al., 1983; Kirkland et al., 1990; Schipper et al., 2008; Cartwright et al., 2010). They are inherent: age-dependent declines in replication and differentiation remain evident in most clones derived from single preadipocytes cultured in parallel from animals of different ages for over a month (Djian et al., 1983; Kirkland et al., 1990). However, these changes do not occur uniformly in every preadipocyte: occasional clones derived from old animals replicate and accumulate lipid like the majority of clones from young animals, and some clones from young animals behave more like cells from old animals (Kirkland et al., 1990).

C/EBPα, PPARγ, and their target genes are lower in preadipocytes cultured from older than younger humans and rats following exposure to differentiation medium (Karagiannides et al., 2001; Schipper et al., 2008). PPARγ and C/EBPα are reduced in fat tissue from various species in old age, including primates (Hotta et al., 1999; Karagiannides et al., 2001). These adipogenic transcription factors also decline in serially passaged human preadipocytes exposed to differentiation-inducing medium, with six population doublings being sufficient to detectably impair adipogenesis (Tchkonia et al., 2006b; Noer et al., 2009). Human preadipocyte replicative arrest occurs after approximately 35 population doublings.

The age-related impairment in adipogenesis occurs at a point between the early increase in C/EBPβ transcription and subsequent increases in PPARγ and C/EBPα (Karagiannides et al., 2001). Overexpressing C/EBPα restores capacity for lipid accumulation by preadipocytes from old individuals. Redundant mechanisms impede adipogenesis at this point, including increased expression of C/EBP homologous protein (CHOP) and an alternatively translated, short C/EBPβ isoform, C/EBPβ liver-activating protein (LIP), that lacks the full C/EBPβ-transactivating domain (Karagiannides et al., 2006b; Tchkonia et al., 2007a). Increased binding of CUG triplet repeat-binding protein (CUGBP) to the 5′ region of C/EBPβ mRNA with aging causes LIP to be translated (Karagiannides et al., 2006b). CUGBP activity, LIP, and CHOP are cellular stress responsive and induced by TNFα. Preadipocyte TNFα secretion, in turn, increases with aging (Tchkonia et al., 2007a). Thus, redundant, stress responsive, inherent processes impair adipogenesis with aging.

Decreased adipogenic transcription factors could contribute to age-related declines in fat cell size, capacity to store lipid, and insulin responsiveness [both PPARγ and C/EBPα are required for fat cells to be insulin–responsive; (El Jack et al., 1999)]. These changes occur at different rates in different depots, with subcutaneous depots being particularly affected, potentially contributing to fat redistribution, lipodystrophy, ectopic lipid accumulation, lipotoxicity, and metabolic dysfunction. Even preadipocytes become susceptible to lipotoxicity because of fatty acids in old age, related to reduced expression of adipogenic transcription factors and enzymes required for processing fatty acids into triglycerides (Guo et al., 2007). Fatty acids also induce fat tissue cytokine release (Suganami et al., 2005), further impeding adipogenesis, leading to a downward spiral. While influences extrinsic to fat tissue, including systemic disease and changes in diet, activity, and hormones, likely contribute to fat dysfunction in old age, inherent, age-related changes in preadipocytes set the stage for fat tissue and systemic metabolic dysfunction.

Reduced PPARγ in mouse models is associated with lipodystrophy and reduced life span (Argmann et al., 2009). An increase in maximum life span owing to manipulating PPARγ would need to be demonstrated before concluding definitively that it is involved in progression of aging. On the other hand, gene knock-in replacement of C/EBPα with C/EBPβ results in increased mean and maximum life span together with leanness, resistance to diet-induced obesity, and increased energy expenditure (Chiu et al., 2004). Thus, age-related changes in preadipocyte and fat cell adipogenic transcription factors may contribute not only to morbidity, manipulating them may also prove to delay age-related dysfunction.

MAD cells

Generation of MAD cells potentially contributes to ectopic lipid accumulation in old age (Kirkland et al., 2002). Preadipocytes are closely related to other mesenchymal progenitors, including osteoblasts, muscle satellite cells, chondroblasts, and macrophages. In old age, muscle satellite cells, osteoblasts, and macrophages can sometimes dysdifferentiate into cells with an incomplete, adipocyte-like phenotype, with lipid accumulation and expression of the fat cell-specific fatty acid-binding protein, aP2, and PPARγ (but insufficient PPARγ for differentiation into fully functional, insulin-responsive fat cells). Failure to express sufficient levels of the transcription factors that direct uncommitted mesenchymal cells into becoming fully functional, specialized cells may contribute to their developing into partially differentiated adipocyte-like cells by default. In muscle, satellite cells from old mice acquire a partial adipocyte phenotype with more lipid accumulation and aP2, C/EBPα, and PPARγ expression than cells from young mice (Taylor-Jones et al., 2002). In bone, osteoblast formation from mesenchymal progenitors is decreased with aging, together with increased adipogenesis (Jilka et al., 1996; Rosen et al., 2009). These changes might contribute to age-related accumulation of fat in bone marrow and muscle as well as osteoporosis.

Preadipocytes in obesity

Increased fat cell size accounts for increased fat mass in mild obesity, while severe obesity leads to increased numbers of fat cells and preadipocytes, together with increased fat cell turnover because of apoptosis and/or necrosis (Shillabeer et al., 1990; Cinti et al., 2005; Lacasa et al., 2007; Strissel et al., 2007). Preadipocytes are driven to become new fat cells in massive obesity, especially in subcutaneous fat, with preadipocyte replicative history being increased (Cinti et al., 2005; Strissel et al., 2007; Thomou et al., 2010). Up to 10 fold more preadipocytes can be present in very massively obese than lean subjects (Table 1). Additionally, preadipocyte turnover is likely increased, because preadipocytes develop into new fat cells as fat cell number and removal increase (Cinti et al., 2005; Strissel et al., 2007).

Table 1.

Preadipocyte abundance is increased in obesity

| Nonobese | Obese | |

|---|---|---|

| Height (m) | 1.65 ± 0.02 | 1.70 ± 0.03 |

| Weight (kg) | 70 ± 6 | 241 ± 6 |

| BMI (m kg−2) | 25 ± 2 | 83 ± 2 |

| Estimated body fat (%) | 20 ± 2 | 58 ± 2 |

| Fat tissue (kg) | 14 ± 2 | 139 ± 5 |

| Preadipocytes per g (×104) | 45 ± 11 | 45 ± 6 |

| Preadipocytes/subject (×109) | 6.1 ± 2.2 | 63.1 ± 9.6 |

Preadipocyte numbers were determined in abdominal subcutaneous fat from five nonobese and 15 massively obese subjects [as in (Kirkland et al., 1994)]. Preadipocytes per g fat tissue differed little between nonobese and obese subjects, as noted by others (van Harmelen et al., 2003). Amount of fat tissue was increased considerably in the obese subjects, resulting in many more preadipocytes/obese subject. The obese subjects had 31 fold more senescent preadipocytes than nonobese subjects (95% confidence limits 13–71), based on preadipocytes/subject and the ratio of SA β–gal+ cells in obese/lean fat tissue (=3.04). Mean ± SEM are shown.

BMI, body mass index.

As in chronological aging and after serial passage in culture (both of which are associated with increased preadipocyte replicative histories), in obesity adipogenesis, C/EBPα, PPARγ, and their downstream targets are decreased in preadipocytes and fat tissue (Turkenkopf et al., 1988; Shillabeer et al., 1990; Permana et al., 2004; Nair et al., 2005; Dubois et al., 2006; Tchkonia et al., 2006b; Gustafson et al., 2009). Stromal vascular cells that are aP2+ (a downstream target of C/EBPα and PPARγ) are reduced in obese women (Tchoukalova et al., 2007). Impaired adipogenesis in obesity, associated with reduced downregulation of preadipocyte pro-inflammatory genes and restricted capacity to store excess fatty acid as triglyceride, may contribute to fat tissue inflammation, ectopic lipid accumulation, lipotoxicity, and insulin resistance, as occurs in aging (Unger, 2002; Xu et al., 2002; Listenberger et al., 2003; DeFronzo, 2004; Tchkonia et al., 2006a; Kim et al., 2007).

Despite low C/EBPα and PPARγ, fat cell size is usually increased in obesity. Differentiating preadipocytes with low C/EBPα and PPARγ can still accumulate lipid when exposed to fatty acids but are insulin resistant and dysfunctional, consistent with accretion of the large, insulin-resistant, C/EBPα- and PPARγ-deficient fat cells in obesity that are associated with diabetes (Xie et al., 2006; Kim et al., 2007). Restricted capacity to increase fat cell number, with increases in fat cell size occurring instead, is associated with lipotoxicity and elevated diabetes risk (Dubois et al., 2006; Kim et al., 2007). Large fat cells in obesity may have restricted capacity to take up excess fatty acid because of: (i) low adipogenic transcription factor expression and consequently impaired machinery to process fatty acids; (ii) insulin resistance with inhibition of IRS-1 and Glut-4; (iii) increased lipolysis with fatty acid release owing to insulin resistance; (iv) instability from their large size, with increased risk of apoptosis/necrosis; and (v) high fat tissue concentrations of TNFα [which is lipolytic and anti-adipogenic; (Cinti et al., 2005; Xie et al., 2006; Gustafson et al., 2009)]. Fat cell dysfunction in obesity, coupled with reduced ability of preadipocytes to differentiate into fat cells, may contribute to failure to sequester fatty acids, systemic lipotoxicity, and insulin resistance.

Fat tissue cellular senescence and inflammation

Cellular senescence

Cellular senescence is considered to be an irreversible block to cell cycle progression in populations of otherwise replication-competent cells (Hayflick & Moorehead, 1961; Narita & Lowe, 2005; Beausejour & Campisi, 2007; Jeyapalan & Sedivy, 2008). Replicative senescence in hyperproliferative states, such as cancer or massive obesity, may constitute a defense against morbidity by removing dysfunctional or excess progenitors from replicating pools of cells (Campisi, 2000, 2004, 2005; Xue et al., 2007). The proportion of arrested cells in a population rises with increasing population doublings, rather than all cells becoming senescent at once (Martin-Ruiz et al., 2004; Passos et al., 2007). This is reflected in vivo in particular regions in different organs in old age, with a subset of cells, often less than 10%, expressing p16 and other markers and effectors of senescence (Krishnamurthy et al., 2004; Wang et al., 2009a). In addition to hyperproliferation, cellular senescence or stasis (Stress or Aberrant Signaling-Induced Senescence) can be induced by stresses: telomere shortening, disrupted chromatin, DNA damage, intense mitogenic signals, oncogene activation, metabolic stress, and stress owing to cell culture conditions (Sherr & DePinho, 2000; Narita et al., 2003; Martin-Ruiz et al., 2004; Campisi, 2005). As in replicative senescence, not all cells in a stressed population undergo stasis at the same time, implying that genetic, epigenetic, or paracrine/microenvironmental conditions confer susceptibility to senescence unequally within cell populations. This could be related to somatic drift among the individual cells in tissues (Martin, 2009). Features of cellular senescence include large, flattened cells, enlarged nucleoli, senescence-associated β-galactosidase [SA β-gal] positivity, and other markers and mediators of senescence, such as phospho-Ser15-p53/p21 and p16/hypophosphorylated Rb pathway component expression. Unlike p21, p16 activity appears to increase in nearly all cells as senescence progresses (Jeyapalan & Sedivy, 2008). SA β-gal+ cells are increased in hyperproliferative diseases [e.g., cancers, psoriasis, prostatic hypertrophy, atherosclerotic plaques; (Choi et al., 2000; Vasile et al., 2001; Narita & Lowe, 2005; Mimura & Joyce, 2006; Jeyapalan & Sedivy, 2008; Charalambous et al., 2007)].

Cellular senescence takes days to weeks to become fully established, with autocrine biochemical loops involving reactive oxygen species (ROS), IL-6, transforming growth factor-β, and other signals eventually resulting in focal accumulation of heterochromatin (Passos et al. 2010; Kuilman et al., 2008; Kuilman & Peeper, 2009; Passos et al., 2009). These heterochromatic foci can be identified by 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) staining and by the activated histones that contribute to DNA repair and stabilization, including γ-phosphorylated histone-2AX [γH2AX; (Wang et al., 2009a)]. In human replicative senescence, heterochromatic foci can be associated with telomeres (telomere-induced foci).

Cellular senescence leads to a senescent secretory phenotype with increased inflammatory cytokines, altered production of ECM-modifying proteases, and production of ROS (Freund et al.; Passos et al. 2010; Krtolica & Campisi, 2002; Parrinello et al., 2005; Xue et al., 2007; Coppéet al., 2008). Generation of cytokines, chemokines, and ECM modifiers by senescent cells leads to death of cells around them, tissue remodeling, and attraction of immune elements. Although senescent cells are often resistant to apoptosis (Campisi, 2003), activation of the immune system by senescent cells causes removal of nearby cells as well as the senescent cells themselves (Xue et al., 2007). Indeed, activation of innate immunity appears to be required for senescent cells to remove nearby cells. The innate immune response capacity of macrophages appears to be compromised with aging (Sebastian et al., 2009), potentially contributing to senescent cell accumulation in old age.

Cellular senescence and inflammation in obesity

Obesity and serial passage both entail repeated preadipocyte replication and cellular stress, as well as accumulation of senescent cells, including senescent preadipocytes and endothelial cells (Minamino et al., 2009; Tchkonia et al., 2009). Adipose tissue SA β-gal activity and p53 increase with BMI. Abundance of SA β-gal+ cells also increases in fat tissue in diabetes. Interestingly, p53 and p21 are increased in the fat cell fraction from subjects with diabetes (Minamino et al., 2009), suggesting a senescent-like state might occur in differentiated adipocytes, even though these cells are postmitotic and therefore would not fit the usual definition of senescence.

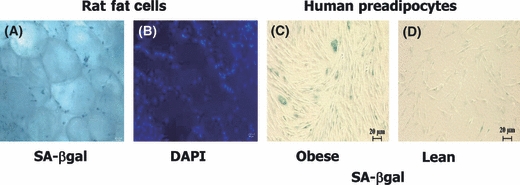

SA β-gal+ cells are more numerous in cultures of preadipocytes and endothelial cells isolated from young obese than lean rats and humans [Fig. 3; (Tchkonia et al., 2009)]. Extremely obese subjects can have a burden of over 30-fold more senescent preadipocytes than nonobese subjects (Table 1). These senescent progenitors in fat tissue might initiate the infiltration of immune cells that commonly occurs in obesity, a speculation that merits testing. Immune cells, in turn, could further activate the preadipocyte population into a pro-inflammatory state. Consistent with this possibility, coculture of 3T3-L1 preadipocytes with RAW264 macrophages without direct contact induces a pro-inflammatory state with increased TNFα expression in the preadipocytes (Suganami et al., 2005). Neutralizing anti-TNFα antibody prevents this.

Fig. 3.

Senescent preadipocytes can accumulate in fat tissue of even young individuals. Freshly isolated, whole perirenal fat tissue isolated from 2-month-old obese male Zucker rats was assayed for senescence-associated β-galactosidase (A; SA β-gal) or stained with DAPI to show nuclei (B; representative of N = 3 animals). Preadipocytes cultured from young obese rats had senescent-associated heterochromatic foci. Senescent cells are also increased in high fat-fed mice, express p53 (Minamino et al., 2009), and are less frequent in age-matched ad libitum fed controls. Human preadipocytes from an obese young adult subject were SA β-gal positive (C; age 21 years.; body mass index [BMI] 50; representative of six obese subjects), while fewer preadipocytes cultured from a lean subject were senescent (D; age 26 years.; BMI 23; representative of nine lean subjects). Nevertheless, occasional senescent cells were found in preadipocytes cultured from all nine young, lean subjects.

A high burden of senescent cells in obesity could have substantial clinical impact because: (i) senescent cells restricted to a single tissue can have widespread systemic effects (Keyes et al., 2006); (ii) many of the pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines released by these cells are associated with development of diabetes and metabolic disease; and (iii) fat is frequently the largest organ in humans. Consistent with this, upregulating p53 in fat cells and macrophages induces senescence and increases insulin resistance and inflammatory cytokines in mouse fat (Minamino et al., 2009). Conversely, expressing dominant-negative p53 in fat cells and macrophages confers protection against the insulin resistance and increased fat tissue cytokines, macrophage infiltration, and SA β-gal activity caused by high fat diets (Minamino et al., 2009). Thus, cellular senescence owing to high p53 and the resulting pro-inflammatory secretory phenotype could contribute to morbidity associated with obesity.

Diabetes itself is associated with cellular senescence in fat tissue. Fat tissue from diabetic humans has increased SA β-gal activity and p53, TNFα, and MCP-1 expression (Minamino et al., 2009). Other fat tissue disorders, such as lipodystrophy in patients with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection treated with certain antiretroviral drugs, cause fat redistribution, diabetes, and metabolic syndrome. The antiretrovirals stavudine and zidovudine cause senescence, with SA β-gal positivity, senescent morphology, and increased p16 and p21, in cultured human fibroblasts and 3T3-F442A murine preadipocytes (Caron et al., 2008). Fat tissue from patients with HIV who are on these drugs can contain senescent cells. Induction of senescence in 3T3-F442A preadipocytes, which are an immortal cell line, indicates these agents can induce preadipocyte senescence independently of replicative history. Cyclo-oxygenase-2 decreases in parallel with induction of senescence by these antiretrovirals, suggesting an association with oxidative stress. Consistent with this, exposure of human preadipocytes to H2O2 causes increased levels of p53, TNFα, and MCP-1 (Minamino et al., 2009).

Fat tissue inflammation and cellular senescence with aging

As in obesity, aging is frequently associated with increased fat tissue and circulating pro-inflammatory cytokines, including TNFα and IL-6 (Morin et al., 1997; Starr et al., 2009). Increased pro-inflammatory cytokine release by preadipocytes activates adjacent cells into a pro-inflammatory state: TNFα exposure increases preadipocyte TNFα mRNA (Mack et al., 2009). Although TNFα and hypoxia also increase preadipocyte cytokines that promote endothelial cell-monocyte adhesion and macrophage infiltration (Mack et al., 2009), macrophages do not appear to be a major source of pro-inflammatory cytokines with aging in fat tissue (Wu et al., 2007). Capacity of macrophages to be activated into a pro-inflammatory state by chemokines and cytokines generally declines with aging (Sebastian et al., 2009). While macrophages increase in particular fat depots with aging, these increases are less impressive than in obesity, and macrophage numbers do not increase at all in some fat depots with aging (Harris et al., 1999; Jerschow et al., 2007). This is consistent with the possibility that fat cells and preadipocytes could be the main sources of the increased fat tissue inflammatory cytokines and chemokines with aging. Preadipocytes from old rats release more TNFα than from young rats, with extent of TNFα release by preadipocytes from old animals being similar to macrophages (Tchkonia et al., 2007a). IL-6 expression is also higher in preadipocytes from old than younger rats (Cartwright et al., 2010). Preadipocytes from old rats and the cytokines they produce can impede adipogenesis in nearby fat cells, potentially contributing to age-related lipodystrophy and fat redistribution (Tchkonia et al., 2007a; Gustafson et al., 2009).

Age-related increases in fat tissue inflammatory cytokine and chemokine expression vary among fat depots (Starr et al., 2009; Cartwright et al., 2010). Basal IL-6, complement factor 1q, and MMP3 and MMP12 increase with aging in extraperitoneal but not intraperitoneal rat preadipocytes (Cartwright et al., 2010). Increases in IL-6 caused by treatment with LPS are sixfold higher in visceral (epididymal) and 33-fold higher in interscapular subcutaneous fat from old (27 months) than younger (6 months) mice (Starr et al., 2009). Thus, the extent of the age-related increase in IL-6 response is 5- to 10-fold greater in subcutaneous than visceral fat, suggesting that age-related changes in fat tissue function are more extensive in subcutaneous than visceral fat. Consistent with this, preadipocyte pro-inflammatory cytokine, chemokine, and ECM modifier production is greater in extra- than intra-peritoneal fat in old age (Cartwright et al., 2010). These differences among depots in the trajectory of age-related preadipocyte dysfunction may contribute to disproportional loss of subcutaneous fat.

Age-related changes in fat tissue inflammatory profiles resemble those in obesity, in which senescent preadipocytes and endothelial cells accumulate, as well as the senescent secretory phenotype reported in skin fibroblasts and other cell types in vitro [Table 2; (Krtolica & Campisi, 2002; Parrinello et al., 2005; Xue et al., 2007; Coppéet al., 2008; Minamino et al., 2009; Tchkonia et al., 2009; Cartwright et al., 2010)]. SA β-gal activity and p16 reactivity are increased in fat tissue of mice with accelerated aging phenotypes owing to hypomorphism of the Bubr1 gene (Baker et al., 2006) and after several generations of telomerase deficiency (Minamino et al., 2009). Importantly, p16Ink4a ablation prevents accumulation of senescent cells in BubR1 hypomorphic mice, implicating p16Ink4a in establishing the senescent phenotype in this model (Baker et al., 2008). Together, these findings suggest senescent cells could accumulate in fat tissue with chronological aging and that these cells might contribute to age-related fat tissue inflammation and dysfunction.

Table 2.

Parallels among preadipocyte and fat tissue changes in obesity, chronological aging, and after repeated replication of cultured preadipocytes and fibroblasts

| Property | Obesity | Repeated replication | Aging |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dysdifferentiation | √ | √* | √ |

| ↑ Inflammation | √ | √ | √ |

| ↑ TNFα, IL6, MMPs, PAI-1 | √ | √† | √‡ |

| Altered progenitor shape | √ | √ | √ |

| Insulin resistance | √ | √ | |

| ↑ Senescence associated β-gal | √§ | √ | √ |

| ↓β oxidation, PGC-1α | √¶ | √ | |

| ↑ Stathmin-like-2 (Stmn-2) | √ | √‡ |

Cell dynamic and molecular mechanisms underlying fat tissue dysfunction in obesity in younger individuals are strikingly similar to aging. Similarities between changes in human preadipocyte and fibroblast function after serial passage in vitro to those in preadipocytes from obese or old subjects further support this (Tchkonia et al., 2006b, 2009). Thus, obesity, in some respects, resembles an accelerated form of fat tissue aging, potentially involving fat cell progenitor hyperplasia and cellular stress.

In (Mu & Higgins, 1995).

In (Semple et al., 2004). Other references appear in the text.

Hypothetical model and potential implications

Cellular senescence could be pivotal in the impact of fat tissue on systemic metabolism and healthspan. Cellular senescence, arguably a normally adaptive response to injury or infection, could instead become a root cause of inflammation, failure to sequester fatty acids, and dysfunction both in fat tissue and systemically during aging and in obesity (Fig. 1). In fat, extensive progenitor turnover, high fatty acid levels, toxic metabolites, prolonged IGF-1 exposure, and other mitogens could initiate senescence. Senescence might then spread from cell to cell, involving differentiated fat cells as well as preadipocytes and endothelial cells. Cytokines and chemokines produced by senescent cells appear to be capable of activating adaptive and innate immune responses that could spread cellular senescence locally and systemically. ECM-modifying proteases might expose fat tissue autoantigens or generate neoantigens, further exacerbating the process. Failure to remove senescent cells may contribute to their accumulation, both because of age-related macrophage dysfunction and effects of ECM-modifying proteases on receptors and other proteins required for optimal immune clearance. If this hypothetical model is valid, senescent cells and their products would be a logical target for therapeutic intervention in age- and obesity-related metabolic disease.

This speculative model and recent findings about fat tissue cellular senescence and inflammation prompt several questions about cellular senescence (Table S1). Among these are the following: (i) Is cellular senescence effectively an alternative form of differentiation? (ii) Can a senescent-like state develop in terminally differentiated cells? (iii) Can senescence occur at any stage during life? (iv) Does senescence spread from cell to cell in fat tissue in vivo? (v) Does failure of the immune system to remove senescent cells contribute to their accumulation in old age? and (vi) Is cellular senescence really at the root of age- and obesity-related fat tissue inflammation and metabolic dysfunction? As discussed later, suggestive evidence supports affirmative answers to some of these questions, but more work is required to address them definitively.

Is cellular senescence effectively an alternative form of differentiation? Cellular senescence can be viewed as a response to cellular stress (Ben-Porath & Weinberg, 2004). In preadipocytes, cellular senescence, the age-associated MAD state, the pro-inflammatory secretory state activated by cytokines, LPS, fatty acids, ROS, ceramide, cellular stress pathways, or other signals, and the macrophage-like phenotype that preadipocytes can assume may all be related. In addition to preadipocytes, other types of progenitors appear to be able to assume a state very much like M1 activated macrophages, based on their gene expression profiles (Charriere et al., 2006). Acquisition of this pro-inflammatory state appears to involve extra- and intracellular signals that integrate to activate: (i) a chain of signaling molecules; (ii) an orchestrated cascade of transcription factors; (iii) banks of pro-inflammatory cytokines, chemokines, and ECM-modifying proteases; (iv) mechanisms that shut down replication; and (v) mechanisms that prevent usual differentiation. Perhaps senescence is an alternative cell fate that has much in common with pro-inflammatory stress-activated states.

Can a senescent-like state develop in terminally differentiated cells? Terminally differentiated fat cells might be able to acquire a senescent-like state in both aging and obesity (Wu et al., 2007; Minamino et al., 2009). Perhaps the view that a cellular senescent-like state can only occur in dividing cells needs reconsideration.

Can senescence occur at any stage during life? If our hypothetical model is correct, cellular senescence should be inducible at any phase in life. Even at early passage, some cells in cultured human skin fibroblast strains express markers of senescence (Martin-Ruiz et al., 2004). The proportion of these cells increases with passaging or following imposition of cellular stress at early passage (Passos et al., 2007). With respect to fat, senescent cells can be found in fat tissue and preadipocytes from juvenile animals and young adult humans with obesity (Fig. 3). The answer to this question appears to be yes.

Does cellular senescence spread from cell to cell? Cultured human cells and mouse cells in vivo that have DNA double-strand breaks and γH2AX induced by radiation can induce DNA damage responses and γH2AX foci in nearby cells (Sokolov et al., 2007). Cytokines secreted by activated preadipocytes, macrophages, and endothelial cells can induce chemokine and cytokine expression in bystander cells in a pattern like that of the senescent secretory phenotype (Suganami et al., 2005; Mack et al., 2009). TNFα induces cellular senescence in preadipocytes, endothelial progenitor cells, and skin fibroblasts (Keyes et al., 2006; Tchkonia et al., 2009; Zhang et al., 2009). Thus, it seems senescence can spread locally from cell to cell. It will be interesting to test whether fat tissue cellular senescence induced by obesity leads to generation of senescent cells elsewhere, such as in the brain. Indeed, high fat feeding induces cellular senescence in aortic endothelium, a process that is mediated by Akt and mTOR and inhibited by rapamycin (Wang et al., 2009b). Whether aortic endothelial senescence results directly from increased circulating lipids owing to the high fat diet, hormones affected by the diet (e.g., insulin or IGF-1), cytokines released by senescent cells in fat or elsewhere, or a combination of mechanisms remains to be determined.

Does failure of the immune system to remove senescent cells contribute to their accumulation in old age? Macrophage function generally declines with aging (Sebastian et al., 2009). Age-related alterations in the stromal microenvironment, including cytokine imbalance, could further impede macrophage function (Stout & Suttles, 2005), possibly augmenting senescent cell accumulation. This question needs to be addressed specifically in fat tissue macrophages, because macrophage properties are highly tissue dependent (Stout & Suttles, 2005; Sebastian et al., 2009).

Is cellular senescence at the root of age- and obesity-related fat tissue inflammation and metabolic dysfunction? The potentially central role of preadipocytes in genesis of fat tissue inflammation and metabolic dysfunction has not received much attention. Preadipocyte cellular stress can result from repeated replication, hypoxia, ROS, chronic effects of free fatty acids or other lipids such as ceramide, hyperglycemia, or other metabolic signals. These appear to activate innate immune responses in preadipocytes, causing further cytokine and chemokine generation, potentially inducing spread of activation of pro-inflammatory responses to nearby preadipocytes and other cell types and attraction of immune cells. The preadipocyte pro-inflammatory phenotype might impede protection against lipotoxicity, contributing to systemic consequences in aging similar to those in lipodystrophies and obesity. The pathways and processes culminating in this generation of activated or senescent preadipocytes and fat cells represent potential new targets for intervention.

It seems a senescent-like, pro-inflammatory fate can be acquired in response to intra- or extracellular danger signals, inflammation, infection, excessive replication, or toxic metabolites. This spectrum of cell fates may prevent differentiation along pathways that are not desirable in the context of damage. In the case of fat tissue, this could involve preventing development of new fat cells or enlargement of existing ones in favor of acquiring cells capable of facilitating repair. Perhaps terminally differentiated cells are able to enter a senescent secretory state related to the molecular pathways that initiate senescence in dividing cell types. Studies in fat tissue are beginning to suggest that cellular senescence could be an alternative cell fate involving activation of pro-inflammatory responses owing to intra- or extracellular injury signals at any stage of life.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to participants of a retreat supported by the Robert and Arlene Kogod Center on Aging for insights incorporated in this article and for the editorial support of Jacqueline Armstrong and Linda Wadum. Supported by NIH grants AG13925 (JLK) and AG31736 (JLK), the Noaber Foundation, and the Ted Nash Long Life Foundation (JLK).

Author contributions

Tamara Tchkonia: concept generation, editing, studies in the tables and figures. Dean E Morbeck, Thomas von Zglinicki, Jan van Deursen, Joseph Lustgarten, Heidi Scrable, Sundeep Khosla: concept generation, editing. Michael D. Jensen: concept generation, editing, studies in Table 1. James L. Kirkland: concept generation, manuscript writing, editing, studies in tables and figures.

Supporting Information

Additional supporting information may be found in the online version of this article:

Table S1 Research questions regarding cellular senescence and fat tissue

As a service to our authors and readers, this journal provides supporting information supplied by the authors. Such materials are peer-reviewed and may be re-organized for online delivery, but are not copy-edited or typeset. Technical support issues arising from supporting information (other than missing files) should be addressed to the authors.

References

- Abel ED, Peroni O, Kim JK, Kim YB, Boss O, Hadro E, Minnemann T, Shulman GI, Kahn BB. Adipose-selective targeting of the GLUT4 gene impairs insulin action in muscle and liver. Nature. 2001;409:729–733. doi: 10.1038/35055575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahima RS. Connecting obesity, aging and diabetes. Nat. Med. 2009;15:996–997. doi: 10.1038/nm0909-996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Argmann C, Dobrin R, Heikkinen S, Auburtin A, Pouilly L, Cock TA, Koutnikova H, Zhu J, Schadt EE, Auwerx J. Ppargamma2 is a key driver of longevity in the mouse. PLoS Genet. 2009;5:e1000752. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atzmon G, Pollin TI, Crandall J, Tanner K, Schechter CB, Scherer PE, Rincon M, Siegel G, Katz M, Lipton RB, Shuldiner AR, Barzilai N. Adiponectin levels and genotype: a potential regulator of life span in humans. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2008;63:447–453. doi: 10.1093/gerona/63.5.447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker DJ, Jeganathan KB, Malureanu L, Perez-Terzic C, Terzic A, van Deursen JM. Early aging-associated phenotypes in Bub3/Rae1 haploinsufficient mice. J. Cell Biol. 2006;172:529–540. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200507081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker DJ, Perez-Terzic C, Jin F, Pitel K, Niederländer NJ, Jeganathan K, Yamada S, Reyes S, Rowe L, Hiddinga HJ, Eberhardt NL, Terzic A, van Deursen JM. Opposing roles for p16Ink4a and p19Arf in senescence and ageing caused by BubR1 insufficiency. Nat. Cell Biol. 2008;10:825–836. doi: 10.1038/ncb1744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barzilai N, Gupta G. Revisiting the role of fat mass in the life extension induced by caloric restriction. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 1999;54:B89–B96. doi: 10.1093/gerona/54.3.b89. discussion B97–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barzilai N, She L, Liu B-Q, Vuguin P, Cohen P, Wang J, Rossetti L. Surgical removal of visceral fat reverses hepatic insulin resistance. Diabetes. 1999;48:94–98. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.48.1.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beausejour CM, Campisi J. Ageing: balancing regeneration and cancer. Nature. 2007;443:404–405. doi: 10.1038/nature05221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Porath I, Weinberg RA. When cells get stressed: an integrative view of cellular senescence. J. Clin. Invest. 2004;113:8–13. doi: 10.1172/JCI200420663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berryman DE, List EO, Coschigano KT, Behar K, Kim JK, Kopchick JJ. Comparing adiposity profiles in three mouse models with altered GH signaling. Growth Horm. IGF Res. 2004;14:309–318. doi: 10.1016/j.ghir.2004.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berryman DE, Christiansen JS, Johannsson G, Thorner MO, Kopchick JJ. Role of the GH/IGF-1 axis in lifespan and healthspan: lessons from animal models. Growth Horm. IGF Res. 2008;18:455–471. doi: 10.1016/j.ghir.2008.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berryman DE, List EO, Palmer AJ, Chung MY, Wright-Piekarski J, Lubbers E, O’Connor P, Okada S, Kopchick JJ. Two-year body composition analyses of long-lived GHR null mice. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2009;65:31–40. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glp175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertrand HA, Masoro EJ, Yu BP. Increasing adipocyte number as the basis for perirenal depot growth in adult rats. Science. 1978;201:1234–1235. doi: 10.1126/science.151328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertrand HA, Lynd FT, Masoro EJ, Yu BP. Changes in adipose mass and cellularity through the adult life of rats fed ad libitum or a life-prolonging restricted diet. J. Gerontol. 1980;35:827–835. doi: 10.1093/geronj/35.6.827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjorntorp P. Obesity and adipose tissue distribution as risk factors for the development of disease. A review. Infusionstherapie. 1990;17:24–27. doi: 10.1159/000222436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bluher M, Kahn BB, Kahn CR. Extended longevity in mice lacking the insulin receptor in adipose tissue. Science. 2003;299:572–574. doi: 10.1126/science.1078223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boney CM, Sekimoto H, Gruppuso PA, Frackelton AR., Jr Src family tyrosine kinases participate in insulin-like growth factor I mitogenic signaling in 3T3-L1 cells. Cell Growth Differ. 2001;12:379–386. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgess-Beusse B, Timchenko NA, Darlington GJ. CCAAT/enhancer binding protein a (C/EBPa) is an important mediator of mouse C/EBPb protein isoform production. Hepatology. 1999;29:597–601. doi: 10.1002/hep.510290245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campisi J. Cancer, aging and cellular senescence. In Vivo. 2000;14:183–188. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campisi J. Cellular senescence and apoptosis: how cellular responses might influence aging phenotypes. Exp. Gerontol. 2003;38:5–11. doi: 10.1016/s0531-5565(02)00152-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campisi J. Fragile fugue: p53 in aging, cancer, and IGF signaling. Nat. Med. 2004;10:231–232. doi: 10.1038/nm0304-231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campisi J. Senescent cells, tumor suppression, and organismal aging: good citizens, bad neighbors. Cell. 2005;120:513–522. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carley AN, Severson DL. Fatty acid metabolism is enhanced in type 2 diabetic hearts. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2005;1734:112–126. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2005.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caron M, Auclairt M, Vissian A, Vigouroux C, Capeau J. Contribution of mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress to cellular premature senescence induced by antiretroviral thymidine analogues. Antivir. Ther. 2008;13:27–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carr DB, Utzschneider KM, Hull RL, Kodama K, Retzlaff BM, Brunzell JD, Shofer JB, Fish BE, Knopp RH, Kahn SE. Intra-abdominal fat is a major determinant of the National Cholesterol Education Program Adult Treatment Panel III criteria for the metabolic syndrome. Diabetes. 2004;53:2087–2094. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.53.8.2087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cartwright MJ, Tchkonia T, Kirkland JL. Aging in adipocytes: potential impact of inherent, depot-specific mechanisms. Exp. Gerontol. 2007;42:463–471. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2007.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cartwright M, Tchkonia T, Lenburg M, Pirtskhalava T, Cartwright A, Lopez MMA, Frampton G, Kirkland JL. Aging, fat depot origin, and fat cell progenitor expression profiles: setting the stage for altered fat tissue function. J. Gerontol. 2010;65:242–251. [Google Scholar]

- Caserta F, Tchkonia T, Civelek V, Prentki M, Brown NF, McGarry JD, Forse RA, Corkey BE, Hamilton JA, Kirkland JL. Fat depot origin affects fatty acid handling in cultured rat and human preadipocytes. Am. J. Physiol. 2001;280:E238–E247. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.2001.280.2.E238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang GR, Chiu YS, Wu YY, Chen WY, Liao JW, Chao TH, Mao FC. Rapamycin protects against high fat diet-induced obesity in C57BL/6J mice. J. Pharmacol. Sci. 2009;109:496–503. doi: 10.1254/jphs.08215fp. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charalambous C, Virrey J, Kardosh A, Jabbour MN, Qazi-Abdullah L, Pen L, Zidovetzki R, Schonthal AH, Chen TC, Hofman FM. Glioma-associated endothelial cells show evidence of replicative senescence. Exp. Cell Res. 2007;313:1192–1202. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2006.12.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charriere G, Cousin B, Arnaud E, Andre M, Bacou F, Penicaud L, Casteilla L. Preadipocyte conversion to macrophage. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:9850–9855. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M210811200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charriere GM, Cousin B, Arnaud E, Saillan-Barreau C, Andre M, Massoudi A, Dani C, Penicaud L, Casteilla L. Macrophage characteristics of stem cells revealed by transcriptome profiling. Exp. Cell Res. 2006;312:3205–3214. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2006.06.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiu CH, Lin WD, Huang SY, Lee YH. Effect of a C/EBP gene replacement on mitochondrial biogenesis in fat cells. Genes Dev. 2004;18:1970–1975. doi: 10.1101/gad.1213104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi J, Shendrik I, Peacocke M, Peehl D, Buttyan R, Ikeguchi EF, Katz AE, Benson MC. Expression of senescence-associated beta-galactosidase in enlarged prostates from men with benign prostatic hyperplasia. Urology. 2000;56:160–166. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(00)00538-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung S, Lapoint K, Martinez K, Kennedy A, Boysen Sandberg M, McIntosh MK. Preadipocytes mediate lipopolysaccharide-induced inflammation and insulin resistance in primary cultures of newly differentiated human adipocytes. Endocrinology. 2006;147:5340–5351. doi: 10.1210/en.2006-0536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cinti S, Mitchell G, Barbatelli G, Murano I, Ceresi E, Faloia E, Wang S, Fortier M, Greenberg AS, Obin MS. Adipocyte death defines macrophage localization and function in adipose tissue of obese mice and humans. J. Lipid Res. 2005;46:2347–2355. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M500294-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke SL, Robinson CE, Gimble JM. CAAT/enhancer binding proteins directly modulate transcription from the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma 2 promoter. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1997;240:99–103. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.7627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colditz GA, Willett WC, Rotnitzky A, Manson JE. Weight gain as a risk factor for clinical diabetes mellitus in women. Ann. Intern. Med. 1995;122:481–486. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-122-7-199504010-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coppé JP, Patil C, Rodier F, Sun Y, Muñoz DP, Goldstein J, Nelson PS, Desprez PY, Campisi J. Senescence-associated secretory phenotypes reveal cell-nonautonomous functions of oncogenic RAS and the p53 tumor suppressor. PLoS Biol. 2008;6:2853–2868. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0060301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cousin B, Munoz O, Andre M, Fontanilles AM, Dani C, Cousin JL, Laharrague P, Casteilla L, Penicaud L. A role for preadipocytes as macrophage-like cells. FASEB J. 1999;13:305–312. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.13.2.305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crossno JT, Majka SM, Grazia T, Gill RG, Klemm DJ. Rosiglitazone promotes development of a novel adipocyte population from bone marrow-derived circulating progenitor cells. J. Clin. Invest. 2006;116:3220–3228. doi: 10.1172/JCI28510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curat CA, Miranville A, Sengenes C, Diehl M, Tonus C, Busse R, Bouloumie A. From blood monocytes to adipose tissue-resident macrophages. Diabetes. 2004;53:1285–1292. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.53.5.1285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cypess AM, Lehman S, Williams G, Tal I, Rodman D, Goldfine AB, Kuo FC, Palmer EL, Tseng YH, Doria A, Kolodny GM, Kahn CR. Identification and importance of brown adipose tissue in adult humans. N. Engl. J. Med. 2009;360:1509–1517. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0810780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das M, Gabriely I, Barzilai N. Caloric restriction, body fat and ageing in experimental models. Obes. Rev. 2004;5:13–19. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789x.2004.00115.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Pergola G, Pannacciulli N. Coagulation and fibrinolysis abnormalities in obesity. J. Endocrinol. Invest. 2002;25:899–904. doi: 10.1007/BF03344054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeFronzo RA. Dysfunctional fat cells, lipotoxicity and type 2 diabetes. Int. J. Clin. Pract. 2004;2004:9–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1368-504x.2004.00389.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denke MA, Sempos CT, Grundy SM. Excess body weight. An underrecognized contributor to high blood cholesterol levels in white American men. Arch. Intern. Med. 1993;153:1093–1103. doi: 10.1001/archinte.153.9.1093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denke MA, Sempos CT, Grundy SM. Excess body weight. An under-recognized contributor to dyslipidemia in white American women. Arch. Intern. Med. 1994;154:401–410. doi: 10.1001/archinte.154.4.401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Djian P, Roncari DAK, Hollenberg CH. Influence of anatomic site and age on the replication and differentiation of rat adipocyte precursors in culture. J. Clin. Invest. 1983;72:1200–1208. doi: 10.1172/JCI111075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubois SG, Heilbronn LK, Smith SR, Albu JB, Kelley DE, Ravussin E. Decreased expression of adipogenic genes in obese subjects with type 2 diabetes. Obesity. 2006;14:1543–1552. doi: 10.1038/oby.2006.178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Einstein FH, Atzmon G, Yang XM, Ma XH, Rincon M, Rudin E, Muzumdar R, Barzilai N. Differential responses of visceral and subcutaneous fat depots to nutrients. Diabetes. 2005;54:672–678. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.3.672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El Jack AK, Hamm JK, Pilch PF, Farmer SR. Reconstitution of insulin-sensitive glucose transport in fibroblasts requires expression of both PPARg and C/EBPa. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:7946–7951. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.12.7946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fain JN, Tagele BM, Cheema P, Madan AK, Tichansky DS. Release of 12 adipokines by adipose tissue, nonfat cells, and fat cells from obese women. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2009;18:890–896. doi: 10.1038/oby.2009.335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farmer SR. Regulation of PPARgamma activity during adipogenesis. Int. J. Obes. 2005;29(Suppl. 1):S13–S16. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferri C, Desideri G, Valenti M, Bellini C, Pasin M, Santucci A, De Mattia G. Early upregulation of endothelial adhesion molecules in obese hypertensive men. Hypertension. 1999;34:568–573. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.34.4.568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feuerer M, Herrero L, Cipolletta D, Naaz A, Wong J, Nayer A, Lee J, Goldfine AB, Benoist C, Shoelson S, Mathis D. Lean, but not obese, fat is enriched for a unique population of regulatory T cells that affect metabolic parameters. Nat. Med. 2009;15:930–939. doi: 10.1038/nm.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freund A, Orjalo AV, Desprez PY, Campisi J. Inflammatory networks during cellular senescence: causes and consequences. Trends Mol. Med. 2010;16:238–246. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2010.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fried S, Kral J. Sex differences in regional distribution of fat cell size and lipoprotein lipase activity in morbidly obese patients. Int. J. Obes. 1987;11:129–140. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fried SK, Bunkin DA, Greenberg AS. Omental and subcutaneous adipose tissues of obese subjects release interleukin-6: depot difference and regulation by glucocorticoid. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 1998;83:847–850. doi: 10.1210/jcem.83.3.4660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabaldon AM, McDonald RB, Horwitz BA. Effects of age, gender, and senescence on beta-adrenergic responses of isolated F344 rat brown adipocytes in vitro. Am. J. Physiol. 1998;274:E726–E736. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1998.274.4.E726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]