Abstract

Endometriosis is a debilitating condition characterized by high recurrence rates. The etiology and pathogenesis remain unclear. Typically, endometriosis causes pain and infertility, although 20–25% of patients are asymptomatic. The principal aims of therapy include relief of symptoms, resolution of existing endometriotic implants, and prevention of new foci of ectopic endometrial tissue. Current therapeutic approaches are far from being curative; they focus on managing the clinical symptoms of the disease rather than fighting the disease. Specific combinations of medical, surgical, and psychological treatments can ameliorate the quality of life of women with endometriosis. The benefits of these treatments have not been entirely demonstrated, particularly in terms of expectations that women hold for their own lives. Although theoretically advantageous, there is no evidence that a combination medical-surgical treatment significantly enhances fertility, and it may unnecessarily delay further fertility therapy. Randomized controlled trials are required to demonstrate the efficacy of different treatments.

Keywords: Endometriosis, Dysmenorrhea, Dyspareunia, Uterine contractility, Infertility

Introduction

Endometriosis is defined as the presence of endometrial-like tissue (glands and stroma) outside the uterus, which induces a chronic inflammatory reaction, scar tissue, and adhesions that may distort a woman’s pelvic anatomy [1]. Endometriosis is primarily found in young women, but its occurrence is not related to ethnic or social group distinctions. Patients with endometriosis mainly complain of pelvic pain, dysmenorrhea, and dyspareunia [2]. The associated symptoms can impact the patient’s general physical, mental, and social well being [1].

Epidemiology

Endometriosis is a very common debilitating disease that occurs in 6 to 10% of the general female population; in women with pain, infertility, or both, the frequency is 35–50% [3]. About 25 to 50% of infertile women have endometriosis, and 30 to 50% of women with endometriosis are infertile [4]. More recent data indicate that the incidence of endometriosis has not increased in the last 30 years and remains at 2.37–2.49/1000/y, which equates to an approximate prevalence of 6–8% [5].

To date, it has not been possible to determine whether a medical approach is less expensive than a surgical approach in patients with chronic pelvic pain. Also, data is lacking regarding the cost of treating endometriosis in infertile patients [6].

On May 10th, 2007, the Public Health Executive Agency of the European Union announced that a €296,000 grant was awarded to a European coalition of universities and patient support organizations to improve the awareness of endometriosis in Europe.

Signs and symptoms

Typically, endometriosis causes pain and infertility, although 20–25% of patients are asymptomatic. Table 1 summarizes the frequency of the more common symptoms of endometriosis.

Table 1.

Common symptoms of endometriosis and rate of occurrence

| Dysmenorrhea | 60–80% |

| Chronic pelvic pain | 40–50% |

| Deep dyspareunia | 40–50% |

| Infertility | 30–50% |

| Severe menstrual pain and irregular flow and/or premenstrual spotting | 10–20% |

| Tenesmus, dyschezia, hematochezia, costiveness, or diarrhea | 1–2% |

| Dysuria, pollakiuria, micro- or macroscopic hematuria | 1–2% |

Other symptoms indicative of endometriosis include pain and a heavy feeling in the lumbo-sacral column and/or legs; nausea, lethargy, chronic fatigue; any cyclical pain affecting other organs; hemoptysis; scapular or thoracic pain; and acute abdomen.

The symptoms of endometriosis do not always correlate with its laparoscopic appearance [7]. The severity of endometriosis symptoms and the probability of its diagnosis increase with age [8, 9]; the incidence peaks in women in their 40s [10].

It may be difficult to differentiate the diagnosis of pelvic pain due to endometriosis from that due to irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), interstitial cystitis, fibromyalgia, and others [11]; however, the involvement of those visceral structures is quite common in patients with endometriosis.

Endometriosis and infertility

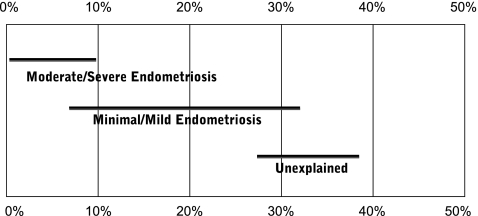

The relationship between endometriosis and infertility has been debated for many years. In normal couples, fecundity is in the range of 0.15 to 0.20 per month and decreases with age. Women with endometriosis tend to have a lower monthly fecundity of about 0.02–0.1 per month [12, 13]. In addition, endometriosis is associated with a lower live birth rate (Fig. 1) [14].

Fig. 1.

The prognosis for live birth among untreated infertile couples. Horizontal lines indicate the cumulative live-births (± CI) recorded at 36 weeks of gestation for different groups of patients [14]

Infertile women are 6 to 8 times more likely to have endometriosis than fertile women [15]. Despite extensive research, no agreement has been reached and several mechanisms have been proposed to explain the association between endometriosis and infertility. These mechanisms include distorted pelvic anatomy, endocrine and ovulatory abnormalities, altered peritoneal function, and altered hormonal and cell-mediated functions in the endometrium.

Based on common observations in laparoscopy, pelvic anatomy distortion, the so-called “pelvic factor”, can more readily explain infertility in patients with severe forms of endometriosis. Major pelvic adhesions or peritubal adhesions that disturb the tubo-ovarian liaison and tube patency can impair oocyte release from the ovary, inhibit ovum pickup, or impede ovum transport [16].

Women with endometriosis may have endocrine and ovulatory disorders, including luteinized unruptured follicle syndrome, impaired folliculogenesis, luteal phase defect, and premature or multiple luteinizing hormone (LH) surges [17].

A complex network of humoral and cellular immunity factors modulates the growth and inflammatory behavior of ectopic endometrial implants and affects embryo implantation. Women with endometriosis have an increased volume of peritoneal fluid with a high concentration of activated macrophages, prostaglandins, IL-1, TNF, and proteases. These alterations may have adverse effects on the function of the oocyte, sperm, embryo, or fallopian tube. Moreover, an ovum capture inhibitor (OCI) in endometriosis peritoneal fluid is thought to be responsible for fimbrial failure of ovum capture [18]. Elevated levels of IgG and IgA antibodies (autoantibodies to endometrial antigens) and lymphocytes may be found in the endometrium of women with endometriosis. These abnormalities may alter endometrial receptivity and embryo implantation [17].

Some authors have reported that uterine implantation was affected by changes in receptivity in endometriosis. Delayed histologic maturation or biochemical disturbances may lead to endometrial dysfunction. Reduced endometrial expression of the αvβ integrin (a cell adhesion molecule) during the time of implantation has been described in some women with endometriosis. Recently, some women with endometriosis exhibited very low levels of an enzyme involved in the synthesis of the endometrial ligand for L-selectin (a protein that coats the trophoblast on the surface of the blastocyst) [17].

Functional disorders of the eutopic endometrium may be closely associated with the presence of ectopic endometrial tissue. For example, abnormal uterine contractions may occur due to a cascade of biochemical products, including prostaglandins, released in the pelvic structures after irritation and inflammation. This theory may explain the failure of implantation in patients with endometriosis: abnormal uterine contractility may interfere with adhesion and subsequent penetration of the embryo on a predecidualized endometrium; this may be a significant factor in the pathophysiology of infertility associated with endometriosis.

Uterine contractility (UC) [19, 20] controls the processes of endometrial shedding at the time of menstruation, transport of gametes, conception, implantation, and maintenance of ongoing pregnancies [21–25]. Abnormal UC patterns are mainly associated with three medical entities: dysmenorrhea [26], endometriosis [27, 28], and infertility [25, 29]. Endometriosis and the presence of endometrial cells in the abdomen were recently related to a specific pattern of UC [30]. An increase of waves in the retrograde direction during menses and the control of these waves may be related to the peristaltic-like contractions that, with a “pumping-like effect”, transport and disseminate endometrial debris into the abdomen [30].

Treatments for endometriosis and infertility

Endometriosis should be viewed as a chronic disease characterized by pelvic pain and associated with infertility. It requires a life-long personalized management plan with the goal of maximizing medical treatment and avoiding repeated surgical procedures. The treatment for endometriosis is essentially chosen by each individual woman, depending on symptoms, age, and fertility. For many women, adequate treatment requires a combination of treatments given over their lifetime. The current treatments include medical, surgical, or a combination of these approaches.

The ablation of the endometrium was effective for reducing unacceptable pain. This may represent an alternative to the removal of the uterus [31]. After endometrial ablation, patients did not exhibit retrograde bleeding or endometriotic implants. In contrast, patients that did not undergo the ablation procedure exhibited a high recurrence rate of endometriosis.

A combination of surgical treatment and either preoperative or postoperative medical therapy has been suggested for endometriosis. Surgical treatment followed by medical treatment may prolong the pain-free (or reduced-pain) interval compared to surgery alone. However, there is insufficient evidence to support the conclusion that hormonal suppression in association with surgery for endometriosis is associated with a significant benefit in pain recurrence or infertility. Endometriosis-associated pain has been well studied, and all the established medical therapies provided a better outcome than placebo [32] (Table 2). However, none seems to be markedly better than another. No studies have demonstrated significant differences in the efficacies of medical and surgical therapies [33–41].

Table 2.

Conventional medical treatment for endometriosis

| Agents | Mechanism | Effect |

|---|---|---|

| Oral contraceptives | decidualization and subsequent atrophy of endometrial tissue | Symptom relief |

| GnRH agonists | down-regulation of the pituitary-ovary axis and hypoestrogenism | Symptom relief and decreased disease |

| Androgens | hyperandrogenism, inhibit steroidogenesis | Symptom relief |

| Aromatase inhibitors | inhibit estrogen synthesis | Symptom relief |

| GnRH antagonists | GnRH receptor blockade | Decreased disease |

| Progesterone antagonists | anti-progesterone | Decreased disease |

| Selective progesterone receptor modulators | suppress estrogen-dependent endometrial growth | Symptom relief |

| Levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system | decidualization and subsequent atrophy o endometrial tissue | Symptom relief |

The clinical management of an infertile couple should take into account the age of the female, duration of infertility, male factor, duration of medical attention, pelvic pain, stage of endometriosis, and family history.

In the management of infertility associated with endometriosis, clinical decisions are difficult because few Randomized Controlled Trials have been conducted to evaluate and compare the effectiveness of the various forms of treatment [42]. Effective, evidence-based treatments of endometriosis-associated infertility include conservative surgical therapy and assisted reproductive technologies. Patients with endometriosis who are interested in fertility may gain limited benefits with medical therapy. Although theoretically advantageous, there is no evidence that the combination of medical and surgical treatments can significantly enhance fertility, and it may unnecessarily delay further fertility therapy [17]. The two treatment options of choice, in this case, include surgery or in vitro fertilization and embryo transfer (IVF-ET) (Tables 3 e 4).

Table 3.

Treatment of endometriosis-associated infertility in confirmed disease

| Medical treatment |

| • Effective for relieving pain associated with endometriosis |

| • There is no evidence that medical therapy improves fecundity |

| • Comparing medical treatment to no treatment or placebo, the common odds ratio for pregnancy was 0,85% (95% CI 0.95, 1,22) [17, 49] |

| • In minimal–mild endometriosis: suppression of ovarian function to improve fertility is not effective and should not be offered for this indication alone [50] |

| • In severe disease: there is no evidence of its effectiveness |

| Surgical treatment |

| • In minimal–mild endometriosis: ablation of endometriotic lesions plus adhesiolysis to improve fertility is effective compared to diagnostic laparoscopy alone [42, 43, 51] |

| • In moderate–severe endometriosis: No Randomized Controlled Trials or meta-analyses are available to answer the question whether surgical excision enhances pregnancy rates |

| • A surgical approach, by normalizing pelvic anatomic distortion and by adhesiolysis, may enchance fertility [44]. Anyway more severe/advanced forms requires a multidisciplinar approach. [47] |

| • After surgical removal of endometriosis: there seems to be a negative correlation between the stage of endometriosis and the spontaneous cumulative pregnancy rate [45, 52–54], but statistical significance was only reached in one study [54] |

| • Laparoscopic cystectomy for ovarian endometriomas >4 cm diameter improves fertility compared to drainage and coagulation [55, 56] |

| • Coagulation or laser vaporization of endometriomas without excision of the pseudocapsule is associated with a significantly increased risk of cyst recurrence [57] |

Table 4.

Assisted reproduction in endometriosis

| IVF is appropriate treatment especially if: | ▪ tubal function is compromised, if |

| ▪ there is also male factor infertility | |

| ▪ other treatments have failed | |

| In moderate–severe endometriosis: prolonged treatment with a GnRH agonist before IVF should be considered and discussed with patients because improved pregnancy rates have been reported [58, 59] | |

| Laparoscopic ovarian cystectomy is recommended: | |

| • ovarian endometrioma ≥4 cm in diameter | |

| • confirm the diagnosis histologically | |

| • improve access to follicles and possibly improve ovarian response | |

| The woman should be counselled regarding the risks of reduced ovarian function after surgery and the loss of the ovary. | |

| The decision should be reconsidered if she has had previous ovarian surgery | |

The surgical removal of endometriotic implants in minimal-mild severity endometriosis was shown to improve fertility in two randomized controlled studies [43, 44]. Thus, all patients with endometriosis should have all visible implants excised during laparoscopic diagnosis. According to Adamson, in the more severe stages of endometriosis, a surgical approach that normalizes pelvic anatomic distortion and provides adhesiolysis can enhance fertility [45].

IVF-ET is particularly appropriate in cases of infertility associated with a history of endometriosis that involve compromised tubal function, male factor, and/or other treatment failures [17]. In particular, IVF-ET is a powerful therapeutic tool for the treatment of infertility-related endometriosis after failure of other lines of treatment. Aboulghar suggested that, when the objective is to treat infertility, IVF-ET without prior surgery would probably be the best option. Thus, patients with a diagnosis of advanced endometriosis may be encouraged to undergo IVF-ET as the first-line treatment, before any attempt at surgical treatment [46].

According to our results, the correct management of infertile women with endometriosis is a combination of surgery and, in the absence of a spontaneous post-surgery pregnancy, IVF-ET. This integrated approach (surgery-IVF-ET) produced a pregnancy rate of 56.1% compared to a significantly lower pregnancy rate of only 37.4% after surgery alone [47].

There is currently insufficient data to clarify whether ovarian endometrioma should be removed in infertile women prior to IVF. Surgery should be envisaged in specific circumstances (Table 5), such as to treat concomitant pain symptoms which are refractory to medical treatments, or when malignancy cannot be reliably ruled out, or in the presence of large cysts (balancing the threshold to operate with the cyst location within the ovary). All decisions to operate a cyst beyond 3 or 4 cm are arbitrary, as there is no evidence to support one or the other. If all healthy growing follicles may be reached without damaging the endometrioma, cyst over 4 or even 5 cm do not require surgery in asymptomatic patients; however, smaller cysts that hide growing follicles, especially when the ovary is fixed, may require intervention.

Table 5.

Endometrioma: clinical variables to be considered when deciding whether to perform surgery or not in women selected for IVF [60]

| Characteristics | Favours surgery | Favours expectant management |

|---|---|---|

| Previous interventions for endometriosis | None | ≥1 |

| Ovarian reserve a | Intact | Damaged |

| Pain symptoms | Present | Absent |

| Bilaterality | Monolateral disease | Bilateral disease |

| Sonographic feature of malignancy b | Present | Absent |

| Growth | Rapid growth | Stable |

aOvarian reserve is estimated based on serum markers or previous hyperstimulation cycles

bSonographic feature of malignancy refers to solid components, locularity, echogeniety, regularity of shape, wall, septa, location and presence of peritonal fluid

No consensus exists for the treatment of mild stage endometriosis, and radical surgery is recommended for cases involving rectovaginal disease. However, the management of endometriosis, especially the more severe/advanced forms, requires a multidisciplinary approach. High success rates in pain reduction, quality of life, sexual activity, and cumulative fertility rates have been reported when surgery was carried out in conjunction with multidisciplinary approaches [48].

Footnotes

Capsule

Endometriosis has a profound impact on quality of life, and developing a therapy that also improves fertility remains a challenge for clinicians and basic scientists.

References

- 1.Kennedy S, Bergqvist A, Chapron C, D’Hooghe T, Dunselman G, Saridogan E, et al. ESHRE guideline on the diagnosis and management of endometriosis. Hum Reprod. 2005;20(10):2698–2704. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dei135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rock JA, Markham SM. Pathogenesis of endometriosis. Lancet. 1992;340:1264–1267. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(92)92959-J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Giudice LC, Kao LC. Endometriosis. Lancet. 2004;364(9447):789–799. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17403-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Counsellor VS. Endometriosis. A clinical and surgical review. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1938;36:877. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(51)90180-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hummelshoj L, Prentice A, Groothuis P. Update on endometriosis. Womens Health (Lond Engl) 2006;2(1):53–56. doi: 10.2217/17455057.2.1.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Simoens S, Hummelshoj L, D’Hooghe T. Endometriosis: cost estimates and methodological perspective. Hum Reprod Update. 2007;13:394–404. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmm010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vercellini P, Trespidi L, Giorgi O, Cortesi I, Parazzini F, Crosignani PG. Endometriosis and pelvic pain: relation to disease stage and localization. Fertil Steril. 1996;65:299–304. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gruppo italiano per lo studio dell’endometriosi Prevalence and anatomical distribution of endometriosis in women with selected gynaecological conditions: results from a multicentric Italian study. Hum Reprod. 1994;9(6):1158–1162. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Berube S, Marcoux S, Maheux R. Characteristics related to the prevalence of minimal or mild endometriosis in infertile women. Canadian Collaborative Group on Endometriosis. Epidemiology. 1998;9:504–510. doi: 10.1097/00001648-199809000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vessey MP, Villard-Mackintosh L, Painter R. Epidemiology of endometriosis in women attending family planning clinics. BMJ. 1993;306:182–184. doi: 10.1136/bmj.306.6871.182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.ACOG Practice Bullettin No 51 Chronic pelvic pain. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;103(3):589–605. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schwartz D, Mayaux MJ. Female fecundity as a function of age: results of artificial insemination in 2193 nulliparous women with azoospermic husbands. CECOS. N Engl J Med. 1982;306(7):404–406. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198202183060706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hughes EG, Fedorkow DM, Cllins JA. A quantitative overview of controlled trials in endometriosis-associated infertility. Fertil Steril. 1993;59:963–970. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Collins JA, Burrows EA, Wilan AR. The prognosis for live birth among untreated infertile couples. Fertil Steril. 1995;64(1):22–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Verkauf BS. The incidence, symptoms, and signs of endometriosis in fertile and infertile women. J Fla Med Assoc. 1987;74(9):671–675. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schenken RS, Asch RH, Williams RF, Hodgen GD. Etiology of infertility in monkeys with endometriosis: luteinized unruptured follicles, luteal phase defects, pelvic adhesions and spontaneous abortions. Fertil Steril. 1984;41:122–130. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(16)47552-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Practice Committee of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine (ASRM) Endometriosis and Infertility. Fertil Steril. 2006;14:S156–S160. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2006.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Suginami H, Yano K. An ovum capture inhibitor (OCI) in endometriosis peritoneal fluid: an OCI-related membrane responsible for fimbrial failure of ovum capture. Fertil Steril. 1988;50:648–653. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(16)60200-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bulletti C, Flamigni C, Ziegler D. Implantation markers and endometriosis. Reprod Biomed Online. 2005;11(4):464–468. doi: 10.1016/S1472-6483(10)61142-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bulletti C, Flamigni C, Ziegler D. Uterine contractility and embryo implantation. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2005;17(3):265–276. doi: 10.1097/01.gco.0000169104.85128.0e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kunz G, Deninger H, Wild L, Leyendecker G. The dynamic of rapid sperm transport through the female genital tract: evidence from vaginal sonography of uterine peristalsis and hysterosalpingoscintigraphy. Hum Reprod. 1996;11:627–632. doi: 10.1093/humrep/11.3.627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bulletti C, Prefetto RA, Bazzocchi G, Romero R, Mimmi P, Flamigni C, et al. Electromechanical activities of human uteri during extra-corporeal perfusion with ovarian steroids. Hum Reprod. 1998;8:1558–1563. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.humrep.a137891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bulletti C, Ziegler D, Polli V, Diotallevi L, Ferro E, Flamigni C. Uterine contractility during menstrual cycle. Hum Reprod. 2000;15:81–89. doi: 10.1093/humrep/15.suppl_1.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ijland MM, Evers JL, Dunselman GA, Hoogland HJ. Endometrial wavelike activity, endometrial thickness, and ultrasound texture in controlled ovarian hyperstimulation cycles. Fertil Steril. 1998;70(2):279–283. doi: 10.1016/S0015-0282(98)00132-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.IJland MM, Evers JL, Dunselman GA, Volovics L, Hoogland HJ. Relation between endometrial wavelike activity and fecundability in spontaneous cycles. Fertil Steril. 1997;67(3):492–496. doi: 10.1016/S0015-0282(97)80075-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dawood MY. Dysmenorrhea. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 1990;33(1):168–178. doi: 10.1097/00003081-199003000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ishimaru T, Masuzaki H. Peritoneal endometriosis: endometrial tissue implantation as its primary etiologic mechanism. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1991;165:210–214. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(91)90253-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Salamanca A, Beltran E. Subendometrial contractility in menstrual phase visualized by transvaginal sonography in patients with endometriosis. Fertil Steril. 1995;64:193–195. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fanchin R, Righini C, Olivennes F. Uterine contractions at the time of embryo transfer alter pregnancy rates in in-vitro fertilization. Hum Reprod. 1998;13:1968–1974. doi: 10.1093/humrep/13.7.1968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bulletti C, Dee Ziegler D, Polli V, Reffo F, Palini S, Flamini C. Characteristics of uterine contractility during menses in women with mild to moderate endometriosis. Fertil Steril. 2002;77(6):1156–1161. doi: 10.1016/S0015-0282(02)03087-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bulletti C, Ziegler D, Stefanetti M, Cicinelli E, Pelosi E, Flamigni C. Endometriosis: absence of recurrence in patients after endometrial ablation. Hum Reprod. 2001;16(12):2676–2679. doi: 10.1093/humrep/16.12.2676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Huang HY. Medical treatment of endometriosis. Chang Gung Med J. 2008;31(5):431–440. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Redwine DB. Conservative laparoscopic excision of endometriosis by sharp dissection: life table analysis and reoperation and persistent or recurrent disease. Fertil Steril. 1991;56:628–634. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(16)54591-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chapron C, Dubuisson JB, Fritel X, Fernandez B, Poncelet C, Pinelli L, et al. Operative management of deep endometriosis infiltrating the uterosacral ligaments. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 1999;6(1):31–37. doi: 10.1016/S1074-3804(99)80037-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sutton C, Hill D. Laser laparoscopy in the treatment of endometriosis. BJOG. 1990;97:181–185. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1990.tb01746.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Donnez J, Nisolle M, Gillerot S, Smets M, Bassil S, Casanas-Roux F. Rectovaginal septum adenomyotic nodules: a series of 500 cases. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1997;104(9):1014–1018. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1997.tb12059.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sutton CJ, Poley AS, Ewen SP, Haines P. Follow up report on a randomized controlled trial of laser laparoscopy in the treatment of pelvic pain associated with minimal to moderate endometriosis. Fertil Steril. 1997;68:1070–1074. doi: 10.1016/S0015-0282(97)00403-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Davis GD. Management of endometriosis and its associated adhesions with the CO2 laser laparoscope. Obstet Gynecol. 1986;68(3):422–425. doi: 10.1097/00006250-198609000-00028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Crosignani PG, Vercellini P, Biffignandi F, Costantini W, Cortesi I, Imparato E. Laparoscopy versus laparotomy in conservative surgical treatment for severe endometriosis. Fertil Steril. 1996;66(5):706–711. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(16)58622-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bateman BG, Kolp LA, Mills S. Endoscopic versus laparotomy management for severe endometriosis. Fertil Steril. 1994;62:690–695. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Busacca M, Fedele L, Bianchi S, Candiani M, Agnoli B, Vignali M, et al. Surgical treatment of recurrent endometriosis: laparotomy versus laparoscopy. Hum Reprod. 1998;13:2271–2274. doi: 10.1093/humrep/13.8.2271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Practice Committee of the American Societ for Reproductive Medicine (ASRM) Treatment of pelvic pain associated with endometriosis. Fertil Steril. 2006;86(5):S18–S27. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2006.08.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Marcoux S, Maheux R, Bérubé S. Laparoscopic surgery in infertile women with minimal or mild endometriosis. Canadian Collaborative Group on Endometriosis. N Engl J Med. 1997;337(4):217–222. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199707243370401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Parazzini F. Ablation of lesions or no treatment in minimal-mild endometriosis in infertile women: a randomized trial. Gruppo Italian per lo Studio dell’Endometriosi. Hum Reprod. 1999;14(5):1332–1334. doi: 10.1093/humrep/14.5.1332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Adamson GD, Baker VL. Subfertility: causes, treatment and outcome. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2003;17(2):169–185. doi: 10.1016/S1521-6934(02)00146-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Aboulghar MA, Mansour RT, Serour GI, AI-Inany HG, Aboulghar MM. The outcome of in vitro fertilization in advanced endometriosis with previous surgery: a case-controlled study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;188(2):371–375. doi: 10.1067/mob.2003.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Coccia ME, Rizzello F, Cammilli F, Bracco GL, Scarselli G. Endometriosis and infertility Surgery and ART: an integrated approach for successful management. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2008;138(1):54–59. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2007.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.D’Hooghe T, Hummelshoj L. Multi-disciplinary centres/networks of excellence for endometriosis management and research: a proposal. Hum Reprod. 2006;21(11):2743–2748. doi: 10.1093/humrep/del123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kennedy S, Bergqvist A, Chapron C, D’Hooghe T, Dunselman D, Greb R, et al. ESHRE guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of endometriosis. Hum Reprod. 2005;20(10):2698–2704. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dei135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hughes E, Brown J, Collins JJ, Farquhar C, Fedorkow D, Vandekerckhove P. Ovulation suppression for endometriosis (Cochrane Review) Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;18(3):CD000155. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000155.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jacobson TZ, Duffy JM, Barlow DH, Farquhar C, Koninckx PR, Olive D. Laparoscopic surgery for subfertility associated with endometriosis (Cochrane Review) Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;20(1):CD001398. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001398.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Adamson GD, Hurd SJ, Pasta DJ, Rodriguez BD. Laparoscopic endometriosis treatment: is it better? Fertil Steril. 1993;59(1):35–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Guzick DS, Silliman NP, Adamson GD, Buttram-VC J, Canis M, Schenken RS, et al. Prediction of pregnancy in infertile women based on the American Society for Reproductive Medicine’s revised classification of endometriosis. Fertil Steril. 1997;67(5):822–829. doi: 10.1016/S0015-0282(97)81392-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Osuga Y, Koga K, Tsutsumi O, Yano T, Maruyama M, Taketani Y, et al. Role of laparoscopy in the treatment of endometriosis-associated infertility. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 2002;53(Suppl 1):33–39. doi: 10.1159/000049422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Beretta P, Franchi M, Ghezzi F, Busacca M, Zupi E, Bolis P. Randomized clinical trial of two laparoscopic treatments of endometriomas: cystectomy versus drainage and coagulation. Fertil Steril. 1998;70(6):1176–1180. doi: 10.1016/S0015-0282(98)00385-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chapron C, Vercellini P, Barakat H, Vieira M, Dubuisson JB. Management of ovarian endometriomas. Hum Reprod Update. 2002;8(6):591–597. doi: 10.1093/humupd/8.6.591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Vercellini P, Chapron C, Giorgi O, Consonni D, Frontino G, Crosignani PG. Coagulation or excision of ovarian endometriomas? Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;188(3):606–610. doi: 10.1067/mob.2003.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Rickes D, Nickel I, Kropf S, Kleinstein J. Increased pregnancy rates after ultralong postoperative therapy with gonadotropin-releasing hormone analogs in patients with endometriosis. Fertil Steril. 2002;78(4):757–762. doi: 10.1016/S0015-0282(02)03338-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Surrey ES, Silverberg KM, Surrey MW, Schoolcraft WB. Effect of prolonged gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist therapy on the outcome of in vitro fertilization–embryo transfer in patients with endometriosis. Fertil Steril. 2002;78(4):699–704. doi: 10.1016/S0015-0282(02)03373-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Garcia-Velasco JA, Somigliana E. Management of endometriomas in women requiring IVF: to touch or not to touch. Hum Reprod. 2009;24(3):496–501. doi: 10.1093/humrep/den398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]