Abstract

Background

End-of-life care (EOLC) discussions and decisions are common in pediatric oncology. Interracial differences have been identified in adult EOLC preferences, but the relation of race to EOLC in pediatric oncology has not been reported. We assessed whether race (white, black) was associated with the frequency of do-not-resuscitate (DNR) orders, the number and timing of EOLC discussions, or the timing of EOLC decisions among patients treated at our institution who died.

Methods

We reviewed the records of 380 patients who died between July 1, 2001 and February 28, 2005. χ2 and Wilcoxon rank-sum tests were used to test the association of race with the number and timing of EOLC discussions, the number of DNR changes, the timing of EOLC decisions (i.e., DNR order, hospice referral), and the presence of a DNR order at the time of death. These analyses were limited to the 345 patients who selfidentified as black or white.

Results

We found no association between race and DNR status at the time of death (p = 0.57), the proportion of patients with DNR order changes (p = 0.82), the median time from DNR order to death (p = 0.51), the time from first EOLC discussion to DNR order (p = 0.12), the time from first EOLC discussion to death (p = 0.33), the proportion of patients who enrolled in hospice (p = 0.64), the time from hospice enrollment to death (p = 0.2) or the number of EOLC discussions before a DNR decision (p = 0.48).

Conclusion

When equal access to specialized pediatric cancer care is provided, race is not a significant factor in the presence or timing of a DNR order, enrollment in or timing of enrollment in hospice, or the number or timing of EOLC discussions before death.

Introduction

Approximately 2,300 children die of cancer each year in the United States.1 Most such deaths are anticipated, and end-of-life care (EOLC) options are commonly discussed and decided.2,3 Racial, ethnic, and cultural characteristics may affect these discussions and decisions. Interracial differences that are relevant to EOLC decision-making have been identified in overall perceptions of the medical system,4,5 spiritual well-being during illness,6 hospice utilization,7 and the exercise of autonomy in medical decision-making.7,8 Furthermore, satisfaction with the health care given to chronically ill children differs by race.9

The relation of race to EOLC in pediatric oncology has not been reported. The equality of access to care at our institution, where no child is denied treatment on the basis of race, religion, or ability to pay, allowed us to investigate whether, in such a setting, race is associated with the use of do-not-resuscitate (DNR) orders, the number or timing of EOLC discussions, or the timing of EOLC decisions.

Methods

Study population and setting

The medical records of all 505 patients treated at St. Jude Children's Research Hospital who died between July 1, 2001 and February 28, 2005 were reviewed after approval by the hospital's Institutional Review Board. St. Jude is a nonprofit pediatric cancer referral center that draws most (85%) of its patients from an 8-state area comprising Tennessee, Mississippi, Illinois, Louisiana, Arkansas, Missouri, Kentucky, and Alabama. All pediatric patients with cancer from this catchment area who are referred by physicians are accepted for treatment; acceptance of patients from other areas depends on protocol eligibility. Demographic factors, insurance status, and ability to pay are never considered. All costs of treatment beyond those reimbursed by third-party payers are absorbed by the hospital.

Inclusion criteria

The inclusion criteria for this analysis were a cancer diagnosis, age less than 22 years at the time of death, and self-identification as white or black on the original intake form. A computerized initial chart review excluded 74 patients on the basis of age and 40 patients because of a non-cancer diagnosis, leaving 391 patients. A detailed review of the paper record excluded another 11 patients because of a non-cancer diagnosis and 35 patients who did not identify themselves as white or black, leaving 345 patients who met the inclusion criteria.

Outcome measures

For this study, we defined a DNR order as any order on the chart that was recorded on our hospital DNR form, regardless of its specific details. When the presence or absence of a DNR order could not be determined (i.e., when parts of the medical record were unavailable for review), a value of “undetermined” was recorded. A change in the DNR order was defined as any clinical change in the previously recorded DNR form, regardless of its specific details. The timing of DNR orders was analyzed on the basis of the date of chart documentation. The timing of hospice referral was analyzed on the basis of the date of hospice enrollment. Study variables that did not involve a DNR order were analyzed on the basis of all available documentation in the group of eligible patients.

An EOLC discussion was identified by documentation in the patient record of a patient and/or family conference with clinician(s) of any discipline that specifically addressed poor prognosis, progressive disease and its implications, patient and/or family preferences for care when cure was no longer possible, or organ failure and its implications. An EOLC discussion could also be identified by documentation of other activities that indicated that a poor prognosis and consequent care decisions had been discussed with the patient and/or family (e.g., documentation of enrollment on a phase I trial).

Data collection

All information for our analysis was collected on an EOLC data form created on the basis of our previous large EOLC chart review,2 our research on EOLC decision-making,10,11 our clinical experience with EOLC decisions, and reported retrospective research methods. Each patient's full medical record was reviewed a second time by a different member of the study team to verify the data. Discrepancies (e.g., in interpretation of chart notes) were resolved by study team discussion or, when necessary, a more focused review of the medical record. Data were then transferred to an Excel spreadsheet (Microsoft, Redmond, WA), and the accuracy of data entry was verified for every third case by a different study team member. A level of accuracy more than 95% (more than 95 data fields verified as correct per 100 comparisons) was maintained.

Statistical analysis

SAS version 9 software12 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) was used for all data analysis. The presence or absence of a DNR order, the proportion of patients with a DNR order change, and hospice enrollment data were analyzed according to race by using the χ2 test. The time from first EOLC discussion to DNR order, the time from first EOLC discussion to death, the time from hospice enrollment to death, and the total number of EOLC discussions prior to a DNR decision were analyzed by using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test. An α level of p = 0.05 was selected.

Results

Patient characteristics

Table 1 shows patient characteristics by race. Race was significantly related only to religious affiliation and referral origin.

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics by Race

| |

|

Race |

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factor | Overall n = 345 (%) | White n = 255 (%) | Black n = 90 (%) | p-value |

| Sex | 0.32 | |||

| Female | 147 (42.6) | 113 (44.3) | 34 (37.8) | |

| Male | 198 (57.4) | 142 (55.7) | 56 (62.2) | |

| Clinical category | 0.14 | |||

| Allo-HSCT | 50 (14.5) | 35 (13.7) | 15 (16.7) | |

| LE | 41 (11.9) | 36 (14.1) | 5 (5.6) | |

| NO | 134 (38.8) | 100 (39.2) | 34 (37.8) | |

| ST | 120 (34.8) | 84 (32.9) | 36 (40.0) | |

| Religious affiliation | 0.003 | |||

| Protestant | 247 (71.6) | 171 (67.1) | 76 (84.4) | |

| Catholic | 58 (16.8) | 50 (19.6) | 8 (8.9) | |

| Not indicated | 28 (8.1) | 22 (8.6) | 6 (6.7) | |

| Other | 12 (3.5) | 12 (4.7) | 0 (0) | |

| Referral origin | <0.001 | |||

| Affiliate institution | 66 (19.1) | 46 (18.0) | 20 (22.2) | |

| International | 12 (3.5) | 12 (4.7) | 0 (0) | |

| Local | 56 (16.2) | 27 (10.6) | 29 (32.2) | |

| Out of State | 211 (61.1) | 170 (66.7) | 41 (45.6) | |

| Place of death | 0.18 | |||

| Home | 184 (53.3) | 137 (53.7) | 47 (52.2) | |

| Community hospital | 51 (14.8) | 32 (12.5) | 19 (21.1) | |

| Unknown | 34 (9.9) | 30 (11.8) | 4 (4.4) | |

| Other | 5 (1.4) | 3 (1.2) | 2 (2.2) | |

| St. Jude Housing | 5 (1.4) | 4 (1.6) | 1 (1.1) | |

| St. Jude Inpatient | 66 (19.1) | 49 (19.2) | 17 (18.9) | |

| Age at diagnosis (y) | 0.10 | |||

| Mean (median) | 8.06 (6.75) | 7.74 (6.63) | 8.96 (8.12) | |

| Age at death (y) | 0.33 | |||

| Mean (median) | 10.68 (10.57) | 10.50 (10.33) | 11.19 (10.93) | |

HSCT, hematopoietic stem cell transplant; LE, leukemia/lymphoma; NO, neurooncology; ST, solid tumor

Categorical variables were compared by using the χ2 test. Continuous variables (i.e., age) were compared by using the t- or rank-sum test.

Presence or absence of a DNR order

Complete medical records were available for 206 of the 345 patients who met the inclusion criteria. The remaining 139 patients died elsewhere, and records from local care providers were not available. The presence or absence of a DNR order was therefore determined in 206 medical records (57 black and 149 white patients). A DNR order was present in the records of 178 patients, 48 (84.21%) of whom were black and 130 (87.25%), white. No significant difference was observed between the proportion of black and white patients who had DNR orders (p = 0.57).

Proportion of patients with DNR order changes

Among the 178 patient records that contained a DNR order, 27 documented a change of the order; 8 (17%) of the changes occurred in black patients and 19 (16%) in white patients (p = 0.82).

Time from DNR order to death

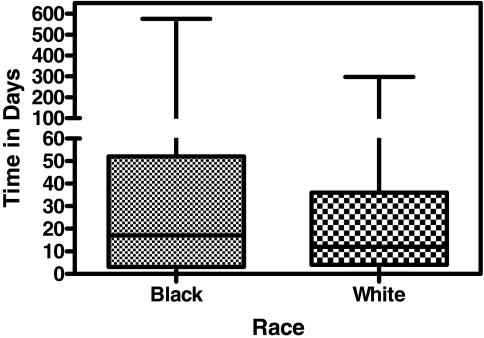

The date of the DNR order and the date of death were documented in 174 patient records (the date of DNR order was not available in 4 charts); 47 of these patients were black and 127 were white. The median time from DNR order to death was 17 days (range, 0–575 days) for black patients and 12 days (0–297 days) for white patients (p = 0.51; Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Time from do-not-resuscitate (DNR) order to death in 174 patients (47 black, 127 white) for whom the date of the DNR order and the date of death were documented.

Time from first EOLC discussion to DNR order

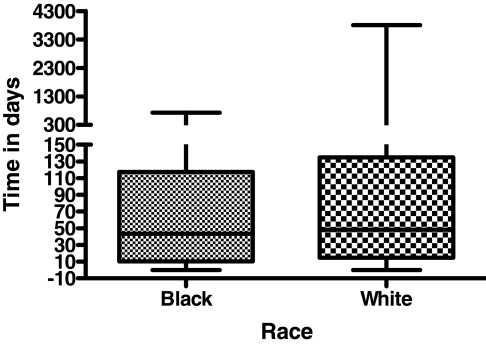

In patients for whom a DNR order and an EOLC discussion were documented, we assessed the association between race and the time between the first documented EOLC discussion and the DNR order. This analysis included 171 patients (3 patients had an undetermined date of first EOLC discussion and the date of DNR order was not available in 4 charts), 47 black and 124 white. The median time from first EOLC discussion to the DNR order was 7 days (range, 0–427 days) for black patients and 2 days (range, 0–1317 days) for white patients. We found no significant difference between black and white patients in the time from first EOLC discussion to the placement of a DNR order (p = 0.12; Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

Time from first end-of-life care (EOLC) discussion to do-not-resuscitate (DNR) order in 47 black and 124 white patients who had a DNR order and at least one documented EOLC discussion.

Number of EOLC discussions

We next analyzed the number of documented EOLC discussions according to race among the 190 patients who made a DNR decision (“yes” or “no”) and had at least one documented EOLC discussion. The median number of EOLC discussions was 3 (range, 1–16) among 53 black patients and 3 (range, 1–25) among 137 white patients. We found no significant difference between the two races in the number of EOLC discussions (p = 0.48, exact Wilcoxon test).

Because there was no demographic difference between the group of patients who died at St. Jude and those who died elsewhere, and because the records of many patients who died elsewhere contained documentation of end-of-life discussions and decisions and of the date of death, the remaining three analyses were conducted in all patients who met the study criteria and whose records contained the relevant information.

Time from first EOLC discussion to death

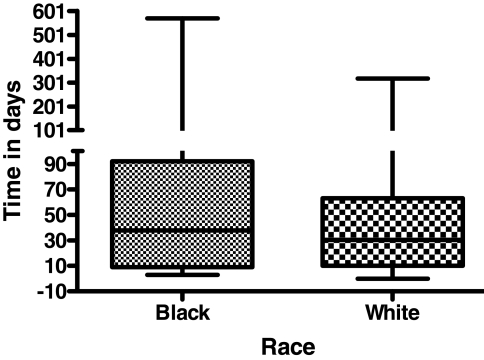

We assessed the association between race and the time from first EOLC discussion to death in all eligible patients who had at least one documented EOLC discussion and whose date of death was recorded (288 patients, 72 black and 216 white). The median time from first EOLC discussion to death was 43.5 (range, 0–730) days in black patients and 48.5 (range, 0–3808) days in white patients (p = 0.33; Fig. 3).

FIG. 3.

Time from first end-of-life care (EOLC) discussion to death in 72 black and 216 white patients who met the study criteria, had at least one documented EOLC discussion, and for whom the date of death was available.

Proportion of patients enrolled in hospice

We analyzed the entire eligible patient cohort to compare the rate of hospice care in black and white patients. Forty of the black patients (41.6%) and 106 of the white patients (44%) enrolled in hospice. The proportion of hospice care did not differ significantly between the two races (p = 0.64).

Time from enrollment in hospice to death

Among the 146 patients who enrolled in hospice and had a known date of death, 19 patient records were missing the specific date of hospice enrollment. The median time from hospice enrollment to death was 38 days (range, 3–570 days) in 35 black patients and 30.5 days (range, 0–318 days) in 92 white patients (p = 0.20; Fig. 4).

FIG. 4.

Time from hospice enrollment to death in 35 black and 92 white patients for whom the date of hospice enrollment and the date of death were documented.

Discussion

The effect of race on EOLC in pediatric oncology has not previously been examined. We found that in a setting such as St. Jude Children's Research Hospital, where access to specialized care is independent of socioeconomic variables, race is not a significant factor in the presence or timing of a DNR order prior to death, enrollment, or timing of enrollment in hospice prior to death, or in the number or timing of EOLC discussions.

Our findings are unexpected in view of those reported in adults. In a systematic review of the literature, Kwak and Haley13 found that EOLC preferences and practices differ substantially in white and non-white racial/ethnic groups. For example, non-white groups were reported to be generally unaware of advance directives and less likely than white groups to support their use. Perkins et al.14 demonstrated specific ethnicity-related differences among Mexican Americans, African Americans, and Euro-Americans; for example, African Americans were more distrustful of the medical system than other groups, and most Mexican Americans and African Americans believed that the medical system controls treatment, while few Euro-Americans shared this belief. Our findings do not contradict the potential value of ethnicity-tailored EOLC discussions. In our setting, however, although the underlying rationale for a decision may differ between white and black patients and families, race is not significantly related to the specific nature or timing of these decisions.

One possible explanation for our findings is the long-term relationships established between pediatric cancer patients and families and their health care providers. Also, because St. Jude is a referral center, patients and their families often make the hospital's housing facilities their home during the child's illness and treatment, developing bonds with other patients and parents. The long-term relationships with clinicians and the parental peer support are likely to build a level of trust and comfort that may not be consistently found in adult care, although their influence on the EOLC decision making process is difficult to ascertain. Furthermore, St. Jude's culture increasingly promotes open discussion, education, and research about end-of-life care and decision making. Over the course of 7½ years (starting 4 years prior to the study eligibility period), a palliative and EOLC task force with a focus on research and education has been created, 3 prospective EOLC decision-making studies have been completed, another such study has been funded by the National Institutes of Health, evidence-based practice guidelines have been implemented to facilitate EOLC decision-making, and a medical director has been named to head the palliative and end-of-life care initiative.15 This focus on all aspects of EOLC promotes clinicians' skill and comfort in approaching families and facilitating the EOLC decision-making process. Despite the possible implications of these factors, however, we are unable to conclusively explain our findings on the basis of currently available information.

Another interesting finding of this study is the unusually high percentage (86%) of both black and white patients who had a DNR order at the time of death. In an earlier study at our hospital, only 48.3% of patients had a DNR order at the time of death. However, all records were included in the earlier analysis, whereas the present analysis included only complete records. A subgroup analysis of stem cell transplant patients in the earlier report demonstrated a percentage (73.9%) more in line with our findings.2 Other groups have reported a frequency of DNR orders ranging from 60% to 90%.3,16,17

This study of patients treated at a single pediatric oncology referral center may not be generalizable to all pediatric oncology patients. One of our study limitations was the inclusion of only black and white races. Other limitations include the retrospective nature of this study, which precludes inferences about causality. Furthermore, we were able to obtain complete data for only 61% of eligible patient because many patients died at other sites; however, race, gender, and diagnosis did not differ significantly between patients with complete versus incomplete records. Finally, this study was limited to information documented in the medical record. It is likely that some clinician conversations with patients and families were not documented.

Our finding that white and black patients and families make similar decisions about EOLC when given equal access to specialized care is consistent with data showing that minority children are proportionally represented in collaborative pediatric oncology trials.18,19 However, while access to and enrollment in such studies may be similar for white and black patients and families, information presented to minority groups during the informed consent process often differs significantly in quality and quantity from that presented to others.18,20 The effect of racial differences in the information process on which EOLC decisions are based has not been adequately examined.

The affective nature of end of life decision-making and the individual complexities inherent in the process warrant further exploration through qualitative study. We also propose that nationally recognized guidelines for pediatric EOLC decision-making support should be developed21 and used to prospectively examine the association of race with EOLC discussions and decisions. Such guidelines should be evidence-based, adaptable to individual cases, and patient- and family-centered, and should take into consideration key quality indicators outlined by the National Quality Forum.22 Our group at St. Jude has created the Individualized Care Planning and Coordination (ICPC) model to facilitate ethical and effective decision making in the pediatric oncology setting. It aims to enhance communication about difficult issues by discerning patient and family values and priorities before critical decision points are reached.23,24 This model is currently theoretical and is unproven in the research realm, but we have found it extremely useful in clinical practice.

Conclusions

When access to specialized pediatric cancer care is independent of socioeconomic variables, race is not a significant factor in the presence of a DNR order at the time of death; the proportion of patients with DNR changes; the total number of EOLC discussions that precede a DNR decision; the time from the first such discussion to a DNR order; the time from the first EOLC discussion to the patient's death; hospice utilization rates; or the time from hospice enrollment to death. The association of race with EOLC discussions and decisions should be prospectively studied using a standardized approach such as the ICPC model to facilitate decision making.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Sharon Naron, M.P.A., E.L.S. for editing and review of the manuscript.

Supported in part by Cancer Center Support Grant P30 CA21765 from the U.S. Public Health Service and by the American Lebanese Syrian Associated Charities (ALSAC)

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.U.S. Cancer Statistics Working Group. United States Cancer Statistics: 1999–2002. Incidence and Mortality Web-based Report. Atlanta: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and National Cancer Institute; 2005. [Feb 19;2007 ]. World Wide Web Center for Disease Control. February 16, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bradshaw G. Hinds PS. Lensing S. Gattuso JS. Razzouk BI. Cancer-related deaths in children and adolescents. J Palliat Med. 2005;8:86–95. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2005.8.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wolfe J. Grier HE. Klar N. Levin SB. Ellenbogen JM. Salem-Schatz S. Emanuel EJ. Weeks JC. Symptoms and suffering at the end of life in children with cancer. N Engl J Med 2000 February. 3;342(5):326–33. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200002033420506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boulware LE. Cooper LA. Ratner LE. LaVeist TA. Powe NR. Race and trust in the health care system. Public Health Rep. 2003;118:358–365. doi: 10.1016/S0033-3549(04)50262-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stepanikova I. Mollborn S. Cook KS. Thom DH. Kramer RM. Patients' race, ethnicity, language, and trust in a physician. J Health Soc Behav. 2006;47:390–405. doi: 10.1177/002214650604700406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tanyi RA. Werner JS. Spirituality in African American and Caucasian women with end-stage renal disease on hemodialysis treatment. Health Care Women Int. 2007;28:141–154. doi: 10.1080/07399330601128486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Colon M. Lyke J. Comparison of hospice use and demographics among European Americans, African Americans, and Latinos. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2003;20:182–190. doi: 10.1177/104990910302000306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.King PA. Wolf LE. Empowering and protecting patients: Lessons for physician-assisted suicide from the African-American experience. Minn Law Rev. 1998;82:1015–1043. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ngui EM. Flores G. Satisfaction with care and ease of using health care services among parents of children with special health care needs: The roles of race/ethnicity, insurance, language, and adequacy of family-centered care. Pediatrics. 2006;117:1184–1196. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-1088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hinds PS. Oakes L. Furman W. Foppiano P. Olson MS. Quargnenti A. Gattuso J. Powell B. Srivastava DK. Jayawardene D. Sandlund JT. Strong C. Decision making by parents and healthcare professionals when considering continued care for pediatric patients with cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum. 1997;24:1523–1528. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hinds PS. Drew D. Oakes LL. Fouladi M. Spunt SL. Church C. Furman WL. End-of-life care preferences of pediatric patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:9146–9154. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.10.538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.The SAS System V9 [computer program] Cary, NC: SAS Institute Inc.; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kwak J. Haley WE. Current research findings on end-of-life decision making among racially or ethnically diverse groups. Gerontologist. 2005;45:634–641. doi: 10.1093/geront/45.5.634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Perkins HS. Geppert CM. Gonzales A. Cortez JD. Hazuda HP. Cross-cultural similarities and differences in attitudes about advance care planning. J Gen Intern Med. 2002;17:48–57. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2002.01032.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Harper J. Hinds PS. Baker JN. Hicks J. Spunt SL. Razzouk BI. Creating a Palliative and End-of-Life Program in a Cure-Oriented Pediatric Setting: The Zig-Zag Method. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs. 2007;24:246–254. doi: 10.1177/1043454207303882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Klopfenstein KJ. Hutchison C. Clark C. Young D. Ruymann FB. Variables influencing end-of-life care in children and adolescents with cancer. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2001;23:481–486. doi: 10.1097/00043426-200111000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McCallum DE. Byrne P. Bruera E. How children die in hospital. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2000;20:417–423. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(00)00212-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bleyer WA. Tejeda HA. Murphy SB. Brawley OW. Smith MA. Ungerleider RS. Equal participation of minority patients in U.S. national pediatric cancer clinical trials. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 1997;19:423–427. doi: 10.1097/00043426-199709000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Howell DL. Ward KC. Austin HD. Young JL. Woods WG. Access to pediatric cancer care by age, race, and diagnosis, and outcomes of cancer treatment in pediatric and adolescent patients in the state of georgia. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:4610–4615. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.07.6992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Simon C. Zyzanski SJ. Eder M. Raiz P. Kodish ED. Siminoff LA. Groups potentially at risk for making poorly informed decisions about entry into clinical trials for childhood cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:2173–2178. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Clarke EB. Curtis JR. Luce JM. Levy M. Danis M. Nelson J. Solomon MZ. Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Critical Care End-Of-Life Peer Workgroup Members: Quality indicators for end-of-life care in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 2003;31:2255–2262. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000084849.96385.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.A National Framework and Preferred Practices for Palliative and Hospice Care Quality. National Quality Forum 2006. www.qualityforum.org. [Feb 19;2007 ]. www.qualityforum.org

- 23.Baker JN. Barfield R. Hinds PS. Kane JR. A process to facilitate decision making in pediatric stem cell transplantation: The Individualized Care Planning and Coordination Model. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2007;13:245–254. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2006.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Baker JN. Hinds PS. Spunt SL. Barfield RC. Allen C. Powell BC. Anderson LH. Kane JR. Integration of palliative care practices into the ongoing care of children with cancer: Individualized care planning and coordination. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2008;55:223–250. doi: 10.1016/j.pcl.2007.10.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]