Abstract

Fear of abandonment has been found to be associated with mental health problems for youth who have experienced a parent's death. This article examines how youth's fears of abandonment following the death of a parent lead to later depressive symptoms by influencing relationships with caregivers, peers, and romantic partners. Participants were 109 youth ages 7-16 (50% male), assessed 4 times over a 6-year period. The ethnic composition of the sample was non-Hispanic Caucasian (67%), Hispanic (16%), African American (7%), Native American (3%), Asian (1%), and Other (6%). Youth's fears of abandonment by their surviving caregiver during the first year of data collection were related to their anxiety in romantic relationships 6 years later, which, in turn, was associated with depressive symptoms measured at 6 years. Youth's caregiver, peer, and romantic relationships at the 6-year follow-up were related to their concurrent depressive symptoms. The relationship between youth's attachment to their surviving caregiver and their depressive symptoms was stronger for younger participants. Implications of these findings for understanding the development of mental health problems following parental bereavement are discussed.

Children's concerns about the security of their relationship with their caregivers have been found to play a role in the development of mental health problems for children who have experienced major relationship disruptions, such as parental divorce or parental death (Wolchik, Tein, Sandler, & Ayers, 2006; Wolchik, Tein, Sandler, & Doyle, 2002). The current article examines how the relationship from children's concerns about the security of their relationship with their caregivers (operationalized as fear of abandonment) to depressive symptoms in adolescence and young adulthood is mediated by their relationships with caregivers, peers, and romantic partners. These relationships will be examined in a sample of parentally-bereaved youth, a group that is at high risk for depression. Using concepts from research on motivation theory (e.g., Skinner & Wellborn, 1994; 1997), attachment theory (e.g., Bowlby, 1969; 1980), and social competence (e.g., Masten & Coatsworth, 1998; Petraitis, Flay, & Miller, 1995), the current article develops and tests theoretical models by which youth's fear of abandonment by their surviving caregiver affects their later romantic, peer, and caregiver relationships, which in turn affect their symptoms of depression.

An estimated 3.4% of American children experience the death of a parent before age 18 (U.S. Bureau of Census, 2001). There is considerable evidence that the death of a parent constitutes a significant risk factor for a variety of negative affective, behavioral, and mental health outcomes, particularly depression (e.g., Cerel, Fristad, Verducci, Weller, & Weller, 2006; Worden & Silverman, 1996). The risk of depression has been found to be three times higher among bereaved youth than among non-bereaved youth (Melhem, Walker, Mortiz, & Brent, 2007). Several prospective longitudinal studies have also found that parental death in childhood is associated with an increased risk for depression in adulthood (Kendler, Sheth, Gardner, & Prescott, 2002; Reinherz, Giaconia, Hauf, Wasserman, & Silverman, 1999).

Motivation theory (Skinner & Wellborn, 1994; 1997) proposes that major life events, such as parenting loss, affect adaptation by threatening children's sense of relatedness, competence, and autonomy. Similarly, Sandler and colleagues (Sandler, 2001; Sandler, Wolchik & Ayers, 2008) view social relatedness as one of the basic needs for healthy adaptation following stressful events, and propose that healthy adaptation following bereavement involves establishing developmentally-appropriate social relationships. Sandler (2001) proposed that children develop “self-systems beliefs” concerning their ability to satisfy their basic needs, and that these belief systems affect the development of mental health problems and well-being.

Fear of abandonment refers to children's beliefs that they cannot count on their caregiver to take care of them in the future. This construct has been used to study the development of problem outcomes for children following major family disruptions of divorce and bereavement (Wolchik et al., 2002; Wolchik et al., 2006). Prospective longitudinal studies with parentally-bereaved children found that fear of abandonment mediated the effects of stressful events and positive parenting on internalizing and externalizing problems and grief symptoms, as assessed about a year later (Wolchik et al., 2006; Wolchik, Ma, Tein, Sandler, & Ayers, 2008). However, researchers have not yet investigated mediating pathways by which fear of abandonment leads to depressive symptoms, particularly in long-term follow-up studies.

Several researchers have proposed that disrupted relationships with the surviving parent or caregiver, and eventually with peers and romantic partners, are one pathway through which parental bereavement leads to the development of depression. For example, a retrospective longitudinal study by Harris, Brown, and Bifulco (1990) found that parental bereavement led to a lack of care by the surviving parent, which led adolescent females to seek support in unhealthy romantic relationships with deviant males. Poor coping with the stressors associated with these unsupportive relationships increased the young women's vulnerability to depression. Hofer's (1984) “hidden regulator model” of grief reactions provides another theoretical explanation for how disrupted relationships increase depression after bereavement. Based on attachment theory, this model proposes that attachment figures provide input to regulate affective, attentional, and security systems. Trauma and distress occur when the attachment partner and his or her regulatory input are lost, and grieving individuals retreat from activities and responsibilities while attempting to reconnect with the lost partner through thoughts and memories. According to this theory, disorganization and depression after bereavement are lessened only when an individual's regulatory system is able to adapt, or when missing regulatory input is provided in another close relationship.

Fear of abandonment and the development of social relationships

Theory and research on parent-child attachment and on social competence support the prediction that fear of abandonment affects the development of a broad array of social relationships. Attachment theory (Bowlby 1969, 1980; Main, Kaplan, & Cassidy, 1985) proposes that parental relationships in childhood provide working models that influence children's later relationships with parents as well as with peers and romantic partners. Fear of abandonment can be conceptualized as one aspect of attachment (Collins, Guichard, Ford, & Feeney, 2004; Cook, 2000). Factor analysis of Hazan and Shaver's (1987) model of attachment inner working models identified anxiety over being abandoned or unloved to be one of three dimensions underlying attachment, along with comfort with dependency and comfort with closeness (Collins & Read, 1990). Roisman and colleagues (Roisman, Madsen, Hennighausen, Sroufe, & Collins, 2001) found that children's observed attachment behaviors with parents at age 13 predicted their reports of attachment to parents at age 19 as well as their observed attachment-related behaviors with romantic partners at ages 20-21. Parentally-bereaved children are likely to have heightened anxiety about being abandoned, therefore threatening the quality of their relationships with caregivers, peers and romantic partners later in life.

Research on the development of social competence, defined as children's effective functioning in developmentally relevant social environments (Ladd, 2005), provides evidence that the security of child-caregiver relationships influences the development of relationships with peers and romantic partners. Studies show that children who are securely attached to a parent are more intimate and better able to give and receive help, and have less conflicted relationships with their best friends (Lieberman, Doyle, Markiewicz, 1999). Insecurely attached children exhibit less social competence than do securely attached children (Bohlin, Hagekull, & Rydell, 2000) and have lower peer acceptance (Kerns, Klepac, & Cole, 1996). A study of male Israeli youth found that youth's attachment-related attitudes and parental attachment style in adolescence predicted their ability to experience intimacy, commitment, and satisfaction in romantic relationships and friendships four years later in young adulthood (Mayseless & Scharf, 2007).

Social relationships and development of depression

Considerable evidence links relationships with parents, peers and romantic partners to depression in childhood and adolescence (Armsden, McCauley, Greenberg, Burke, & Mitchell, 1990; Muris, Meesters, van Melick, & Zwambag, 2001), young adulthood (Margolese, Markiewicz, & Doyle, 2005), and adulthood (Williams & Risking, 2004). For example, college students’ attachments to romantic partners, and to mothers for females, have been found to be uniquely predictive of depressive symptoms (Margolese, Markiewicz, & Doyle, 2005). Similarly, failure to achieve social competence in peer relationships has been linked to mental health problems, including internalizing, externalizing, and substance use problems (e.g. Burt, Obradovic, Long, & Masten, 2008; Petraitis, Flay, & Miller, 1995). For example, social competence with peers in middle childhood has been found to predict changes in depressive symptoms during early adolescence (Cole, Martin, Powers, & Truglio, 1996) and has been found to be related to internalizing symptoms 10 years later, in early adulthood (Burt, et al., 2008).

The Current Study

The current study tested three pathways by which fear of abandonment in parentally-bereaved children and adolescents led to depressive symptoms six years later, when the youth were in later adolescence or young adulthood. In the first model, the relationship between youth's fears of abandonment by the surviving caregiver during the first year of data collection and their depressive symptoms six years later was hypothesized to be mediated by their social competence, as measured six years later. In the second model, the link between fear of abandonment during the first year of data collection and depressive symptoms six years later was hypothesized to be mediated by adolescent/young adults’ romantic attachments measured at the six-year follow-up. In the third model, the relationship between youth's fears of abandonment during the first year of data collection and their depressive symptoms six years later was hypothesized to be mediated by their attachment to the surviving caregiver measured at six year follow-up. Support for the last model may represent a continuity of earlier attachment problems, whereas support for the mediating role of peer and romantic relationships would indicate that the earlier attachment problems affect youth's depressive symptoms through their influence on other developmentally-significant social relationships. We tested the relationships of these social relationship variables to youth's depressive symptoms as reported by the youth and their caregivers. Although parent- and child-report measures of symptomatology often have poor correspondence (Cantwell, Lewinsohn, Rohde, & Seeley, 1997), reports from additional informants, particularly parents, are useful in measuring youth's psychiatric symptoms (Jensen et al., 1999; Rudolph & Lambert, 2007).

This study also examined whether the youth's gender and age moderated the relationships between fear of abandonment, social relationships, and depressive symptoms. On the basis of past research, we predicted that the relationship between fear of abandonment and later social relationships and depressive symptoms would be stronger for girls and young women than for boys and young men. Social relationships are theorized to have a larger impact on mental heath for girls than for boys because of girls’ greater interpersonal and affiliative needs and associated vulnerability to relationship stressors (Cyranowski, Frank, Young, & Shear, 2000). Girls’ higher levels of relationship stress (Leadbeater, Kuperminc, Blatt, & Hertzog, 1999) and greater emotional sensitivity to social stressors (Rudolph & Flynn, 2007) as compared to boys are also related to their higher risk of depression.

We predicted that the link between youth's fear of abandonment, their attachment to their surviving caregiver, and their depressive symptoms would be stronger for younger (ages 14 to 18) compared to older participants (ages 19 to 22), and that youth's relationships with peers and romantic partners would be more strongly related to depressive symptoms for older than for younger participants. These hypotheses are based on literature that documents decreasing interdependence and closeness in adolescent-caregiver relationships as peer and romantic relationships increase in salience (e.g. Collins & Laursen, 2004; Laursen & Williams, 1997).

Methods

Participants

Participants were a subgroup of families who participated in the self-study control condition of a randomized experimental trial of a preventive intervention for parentally-bereaved youth. Eighty-one families (with 109 children and adolescents) were randomly assigned to the self-study control condition. The current sample consisted of the 99 children and adolescents (91% of the self-study group) who participated in all four waves of data collection. Youth age ranged from 7 to 16 at the initial data collection (M = 11.3, SD = 3.22). Parental death had occurred between 3 and 29 months prior to initial data collection (M = 9.4 months, median = 8 months, SD = 4.9). Fifty percent of the youth were male. Ethnicity was non-Hispanic Caucasian (67%), Hispanic (16%), African American (7%), Native American (3%), Asian or Pacific Islander (1%), and Other (6%). Cause of parental death was as follows: illness (68%), accident (20%), and homicide or suicide (12%). Median family income ranged from $30,001 to $35,000 annually. Approximately 62% of the sample had a female caregiver.

A full description of recruitment and eligibility criteria has been presented elsewhere (Sandler et al., 2003) and will only be briefly described here. Participants were recruited using a number of methods, including media presentations, articles in community newsletters, presentations to agencies that had contact with bereaved families, and mail solicitation. Participation was dependent on multiple eligibility criteria including: a) death of a biological parent or parent figure between four and 30 months prior to the beginning of the intervention, b) at least one youth in the family was between 8 and 16 years of age, and c) family members were not currently receiving other mental health or bereavement services. All children from the families who met the criteria were invited to participate.

Measures

Fear of Abandonment

The 14-item Fear of Abandonment Scale, an adaptation of a subscale of the Children's Problematic Beliefs Regarding Parental Divorce questionnaire (CBAPS, Kurdek & Berg, 1987), contains the six original items from the CBAPS fear of abandonment scale and eight additional items added during a previous study of divorcing families (Wolchik et al., 2002). This measure assesses children's fears that their primary caregiver will leave them or no longer care for them in the future, and has been found to predict mental health problems in bereaved children and children from divorced families (Wolchik et al., 2002; Wolchik et al., 2006). Language was slightly altered to be applicable to parentally-bereaved youth (Wolchik, Tein, Sandler, & Ayers, 2005) and the response format was changed from yes/no to a scale from 1 (Not at all true) to 4 (A lot true). Youth rated their agreement with statements such as “Your [parent/guardian] still loves you,” and “You sometimes wonder who you would live with if your [parent/guardian] left you all alone.” This measure was administered at the initial data collection, three-month follow-up, and 14-month follow-up. Internal consistency of the scale in the current sample at was good at initial data collection (α = .77). Correlations between fear of abandonment scores across the three time points were high (median r = .54, p < .0001). Based on Kenny and Zautra's (1995) recommendation to average scores across time points when they are highly correlated and indicative of a relatively stable construct, we averaged fear of abandonment scores across the three time periods to represent a more stable construct.

Peer Competence

The 7-item youth-report version of the Coatsworth Competence Scale's Peer Competence subscale (Coatsworth & Sandler, 1993, adapted from Harter, 1982) was used to measure social competence in peer interactions six years after initial data collection. The items include statements such as “Compared to other kids, I have a lot of friends.” Participants rated the statements on a scale of 1 (Very much like me) to 4 (Not at all like me). The scale was developed for use with children, but has adequate psychometric properties when used with adolescents (Specarelli et al., 1995), and has been found to relate to other measures of peer competence. Cronbach's alpha was .71 in our sample.

Romantic Attachment Anxiety and Avoidance

Brennan, Clark, and Shaver's Experiences in Close Relationships Questionnaire (ECR, 1998) was completed by adolescents and young adults six years after initial data collection. The 36-item measure assesses anxiety (e.g. “I need a lot of reassurance that I am loved by my partner”) and avoidance (e.g. “I try to avoid getting too close to my partner”) in romantic relationships. Respondents are asked to think about romantic relationships in general rather than a specific relationship and rate their agreement with statements on a seven-point scale (1 = disagree strongly, 7= agree strongly). Although created for adults, Brennan (personal communication, 2001) stated that the scale can be used with younger participants who have not yet had a romantic relationship by asking them to imagine how they might feel in a romantic relationship. As recommended by Shaver (2005, personal communication), the anxiety and avoidance scores were used as separate measures. The two subscales have been found to have good construct validity in a wide variety of samples (e.g. Brennan et al., 1998; Mikulincer & Florian, 2000). Cronbach's alphas in the current sample were .93 for Anxiety and .93 for Avoidance.

Caregiver-Adolescent Attachment

Adolescents and young adults completed the 28-item Parent Attachment subscale of the Inventory of Parent and Peer Attachment (IPPA; Armsden & Greenberg, 1987) to measure the security of their attachment to their surviving caregiver at the six-year follow-up. The IPPA has been found to predict a number of mental health and developmental outcomes, including depression and psychological adjustment (Armsden & Greenberg, 1987; Cotterell, 1992). The measure was developed with a sample ages 16-20, but has been used with children as young as 10 (Armsden, McCauley, Greenberg, Burke, & Mitchell, 1990). Youth respond on a five-point scale (1 = Almost always or always true; 5 = Almost never or never true) to items that assess trust (e.g. “My [caregiver] respects my feelings”), communication (e.g. “I tell my [caregiver] about my problems and troubles”), and alienation (e.g. “I get upset a lot more than my [caregiver] knows about”). Cronbach's alphas for the Trust, Communication, and Alienation scores in the current sample were .92, .89, and .86, respectively. A composite score was created by adding the Trust and Communication scores and subtracting the Alienation score, as recommended by the authors of the inventory.

Depressive symptoms

Adolescent/young adult depressive symptoms were assessed using self-report and caregiver-report measures at six-year follow-up. The caregiver-report measure consisted of the 13-item DSM-IV Scale Affective Problems from either the Child Behavior Check List (CBCL, Achenbach, 1978; Achenbach & Edelbrock, 1979) for youth under age 18 or the same subscale of the Young Adult Behavior Check List (YABCL) for those 18 or older. Self-report consisted of the 13-item DSM-IV Scale Affective Problems from the Youth Self Report Survey (YSR, Achenbach, 1991) for youth under age 18 and the same subscale of the Young Adult Self Report Survey (YASR, Achenbach, 1997) for those 18 or older. The DSM-IV Scale Affective Problems items (Achenbach & Dumenci, 2001; Achenbach, Dumenci, & Rescorla, 2003) reflect symptoms of dysthymia and Major Depressive Disorder, and the scale has been found to have good validity in terms of significant agreement with DSM-IV-based clinical diagnoses of depressive disorders using other assessment instruments (van Lang, Ferdinand, Oldehinkel, Ormel, & Verhulst, 2005). Whereas depression and anxiety items often load together on scales such as the CBCL “Anxious/Depressed scale,” reflecting the frequent comorbidity of mood and anxiety disorders, the DSM-IV-oriented scales partition depression and anxiety onto separate factors (Achenbach, Dumenci, & Rescorla, 2003). The items of the Affective Problems scales are identical on the CBCL, YABCL, YSR, and YASR, with the exception of one item (“Enjoys little”), which was excluded from analyses. Cronbach's alphas were .77 for the YSR and YASR, .69 for the CBCL, and .71 for the YABCL in our sample. Caregiver- and self-report scores were used in separate models.

Scores on the DSM-IV Scale Affective Problems from the CBCL at initial data collection were used as a covariate in the analyses that used caregiver reports of adolescent/young adult depression. The YSR was not administered at the initial data collection, so scores on the Child Depression Inventory (CDI, Kovacs, 1981) at initial data collection were used as a covariate in analyses that used self-reported depressive symptoms. The CDI is a 27-item child-report inventory that assesses cognitive, affective, and behavioral symptoms. It contains items such as “I am sad all the time,” and “Many bad things are my fault,” that are rated on a scale from 0 to 2 for the past two weeks. Reliability for the CDI at initial data collection was .87.

Procedure

Four assessments were conducted

Time 1 data was collected prior to random assignment to the experimental or self-study conditions. Times 2, 3, and 4 were collected three months, fourteen months, and six years, respectively, after Time 1. Youth/young adults and caregivers were interviewed separately by trained interviewers, with most interviews occurring at the family home and a few taking place at the university. Adults signed informed consents and minors signed assent forms. At the first three data collections, caregivers received $40 as compensation for interviews concerning one child, with an additional $30 for each additional child. At Time 4, caregivers and youth each received $175 compensation for the interviews, and caregivers received an additional $100 for each interview concerning an additional child.

Results

The mean, variance, skewness, and kurtosis for each scale are provided in Table 1 along with n's for each variable. Skewness of less than 2 and kurtosis of less than 7 are considered acceptable for normality (West, Finch, & Curran, 1995). None of the variables exceeded these cutoffs. The n's for each variable ranged from 79 to 109 observations. Data were missing due to not having some youth participate in the final wave of data collection (n = 10) or not completing at least 80% of the items on a given measure. Preliminary analyses showed that participants with missing data did not differ from participants with complete data on gender, family income, minority ethnic group membership, or initial measures of depressive symptoms or fear of abandonment. However, older teens and young adults were more likely to have missing data (t = 2.53, p = .01), most likely because they were no longer living at home and were more difficult to contact at follow-up.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics for all variables: Mean, standard deviation, skewness, kurtosis, sample size

| Variable | Mean | Standard Deviation | Skewness | Kurtosis | n |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fear of abandonment (Avg. T1-T3) | 1.66 | .41 | .67 | .12 | 96 |

| T4 Peer Competence | 3.16 | .46 | −.67 | .42 | 99 |

| T4 Romantic Attachment Anxiety | 3.22 | 1.37 | −.47 | −.30 | 92 |

| T4 Romantic Attachment Avoidance | 3.02 | 1.07 | .02 | −.85 | 79 |

| T4 Secure Caregiver Attachment | 3.72 | .68 | −.82 | .87 | 95 |

| T1 Self-Reported Depression (CDI) | 9.61 | 6.99 | 1.08 | .84 | 109 |

| T4 Self-Reported Depression (YSR) | 5.03 | 3.96 | .85 | .23 | 98 |

| T1 Caregiver-Report Depression (CBCL) | 3.14 | 3.32 | 1.12 | .47 | 89 |

| T4 Caregiver-Report Depression (CBCL) | 2.51 | 2.86 | 1.26 | .99 | 101 |

| Age | 11.32 | 2.22 | .27 | −.82 | 109 |

| Gender | 1.48 | .50 | .08 | −2.02 | 109 |

Note: Scale scores were created by averaging item scores, as indicated by the creators of the measures. CDI scores are sum of scores on all items.

Pearson product moment correlations for the study variables are presented in Table 2. Significant correlations were found between the composite Time 1-3 (0-14 month) fear of abandonment scores and Time 4 (6 year) depressive symptoms scores as reported by the adolescents/young adults and caregivers and Time 4 romantic attachment anxiety. The four social relationship mediators measured at six-year follow-up were correlated with each other and were each correlated with scores on caregiver- and youth-reports of depressive symptoms measured at six-year follow-up.

Table 2.

Pearson Product Moment Correlations for All Variables

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. T1-3 Fear of Abandonment | 1.0 | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| 2. T4 Peer Competence | −.02 | 1.0 | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| 3. T4 Romantic Anxiety | .33 | −.26* | 1.0 | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| 4. T4 Romantic Avoidance | .00 | −.27* | .30** | 1.0 | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| 5. T4 Caregiver Attachment | −.19 | .36*** | −.30** | −.45*** | 1.0 | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| 9. T1 Depression (SR) | .59*** | −.17 | .31** | .14 | −.28** | 1.0 | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| 10. T1 Depression (CR) | .29** | −.18 | .16 | .16 | −.08 | .27** | 1.0 | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| 11. T4 Depression (SR) | .27** | −.43*** | .44*** | .32** | −.40*** | .32** | .16 | 1.0 | -- | -- | -- |

| 12. T4 Depression (CR) | .26* | −.26* | .23* | .34** | −.28** | .37*** | .39*** | .50*** | 1.0 | -- | -- |

| 13. Gender | .19 | −.12 | .14 | .17 | −.11 | .15 | .08 | −.08 | .03 | 1.0 | -- |

| 14. Age | −.24* | .08 | .02 | −.21 | .23* | −.07 | .37*** | .12 | −.08 | .00 | .10 |

p < .05

p < .01

p < .001

Note: SR = Youth Self Report, CR = Caregiver Report

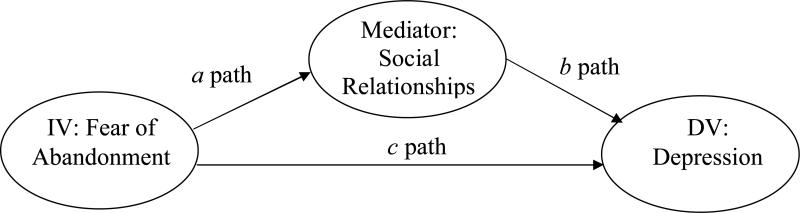

Four mediational models were tested using the composite of Time 1, 2 and 3 fear of abandonment scores and depressive symptoms as measured six years after program completion or five years after Time 3. These models are half-longitudinal, meaning that the independent variable was assessed at a separate time point from the mediators and dependent variables, which were assessed simultaneously. That is, fear of abandonment assessed at Times 1, 2, and 3 (zero, three, and fourteen months) predicts the mediator and depressive symptoms, which were assessed at Time 4, five years following the last assessment of fear of abandonment. Two equations are necessary to establish mediation (see Figure 1): an equation for the a path in which the independent variable significantly predicts the mediator variable, and an equation for the b path in which the mediator variable significantly predicts the dependent variable after controlling for the independent variable (MacKinnon, 2008). This method of assessing mediation has more statistical power than methods that require a c path equation in which the independent variable predicts the dependent variable, as described by Baron and Kenny (1986).

Figure 1.

Pathways of a mediational model

Participants were nested within families (average of 1.6 children per family), and intraclass correlations (ICCs) were calculated to determine whether analyses must account for similarities between family members. Because most of the variables had ICCs above .10, including fear of abandonment at Times 1-3 (.339) and peer competence (.172), caregiver attachment (.187) and caregiver-reported depressive symptoms (.507) at Time 4, we accounted for clustering in our analyses. A power table (Cohen, 1988) was consulted to determine the power needed to detect a medium effect size of .30. For a sample of 100, power to detect a medium effect size of .30 is .86.

Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) with Mplus software (Version 5.2, Muthén & Muthén, 2008) was used to test the meditational models. Each mediator was tested in a separate model, controlling for age, gender, and depressive symptoms at initial data collection (Time 1). Full Maximum Likelihood estimation with missing data (FIML) in MPlus was used to account for missing scale scores. FIML estimates parameter values of interest that best fit the available raw data while accounting for clustering within families, and has been shown to be superior to traditional missing data techniques (see Schafer & Graham, 2002).

To test whether each of the four social relationship variables mediated the relationship between childhood fear of abandonment and depressive symptoms, the coefficients for the a and b paths were multiplied to calculate the mediated effect and the standard error was used to construct confidence limits (MacKinnon & Dwyer, 1993; Sobel, 1982). A computer program was used to calculate an asymmetric confidence interval to determine the significance of the z-statistic and a 95% confidence interval for the mediated effect, as recommended by MacKinnon, Fritz, Williams, and Lockwood (2007). Pearson partial correlations were calculated as indicators of effect size. The a and b path beta estimates for each mediator with adolescent/young adult and caregiver reports of depressive symptoms, Pearson partial correlations for a and b paths, 95% confidence intervals for the mediated effects, and Chi Square values for each model are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Beta estimates (Standard Errors) and Partial Correlations for a and b Paths, Mediated Effect (a*b), Confidence Interval for the Mediated Effect (95% CI), and Chi Square Test of Model Fit for Each Mediational Model.

| Outcomes at 6-year Follow-up (Time 4) |

||

|---|---|---|

| Mediator | Self Report of Depressive Symptoms | Caregiver Report of Depressive Symptoms |

| Peer Competence (Time 4) | ||

| β for a path (SE), partial corr. | −.02 (.12), −.01 | −.01 (.12), .01 |

| β for b path (SE), partial corr. | −3.11(.63)***, −.40**** | −1.08 (.59)+, .21* |

| a*b (95% CI) | .01 (−.68 to .81) | .01 (−.26 to .29) |

| Chi Square | X2(1)=3.54, p =.06 | X2(1)=1.75, p =.19 |

| Romantic Anxiety (Time 4) | ||

| β for a path (SE), partial corr. | 1.05 (.33)***, .27** | 1.1 (.33)***, .30* |

| β for b path (SE), partial corr. | .93 (.30)**, .33**** | .33 (.23), .13 |

| a*b (95% CI) | .98 (.26 to 1.96) | .36 (−.11 to .98) |

| Chi Square | X2(1)=2.46, p =.12 | X2(1)=.30, p =.59 |

| Romantic Avoidance (Time 4) | ||

| β for a path (SE), partial corr. | −.28 (.31), .10 | −.26 (.31), .10 |

| β for b path (SE), partial corr. | 1.07 (.41)**, .31** | .89 (.31)**, .40*** |

| a*b (95% CI) | −.30 (−1.09 to .32) | −.23 (−.87 to .29) |

| Chi Square | X2(1)=2.29, p =.13 | X2(1)=2.76, p =.10 |

| Caregiver Attachment (Time 4) | ||

| β for a path (SE), partial corr. | −.23 (.19), −.09 | −.22 (.19), .13 |

| β for b path (SE), partial corr. | −2.07 (.61)**, −.33*** | −1.10 ( .48)*, .26* |

| a*b (95% CI) | .48 (−.26 to 1.40) | .24 (−.14 to .79) |

| Chi Square | X2(1)=4.27, p =.04 | X2(1)=.01, p =.91 |

p < .10

p < .05

p < .01

p < .001

p < .0001

Note: Analyses controlled for gender, age, and depressive symptoms at Time 1.

Note: Partial correlations were calculated using listwise deletion

The mediational model with youth's romantic attachment anxiety measured at six years and youth's/young adults’ reports of depressive symptoms at six years as the outcome had a significant a path and b path and showed satisfactory fit (χ2 (1) = 2.45; p = .12). The 95% confidence interval for the mediated effect in this model did not contain zero and is therefore statistically significant. The other models with youth's or young adults’ reports of depressive symptoms had significant b paths but not a paths. The overall fit was not satisfactory for the models with peer competence at six years (X2(1)=3.54, p =.06), romantic attachment avoidance at six years (χ2 (1) = 2.29, p =.13), and caregiver attachment at six years (X2(1)=4.27, p =.04) as the mediators. The 95% confidence intervals of the mediated effects for these models contained zero and were therefore nonsignificant. For the models with caregiver reports of depressive symptoms as the outcome, the a path was significant for the putative mediator of romantic attachment anxiety, and only the b path was significant for the models with the other three mediators. Although some of these models had good overall fit (see Table 3), the 95% confidence interval for the mediated effects of these models were consistent with nonsignificant mediation effects.

For the model in which romantic attachment anxiety at the six-year follow-up was a significant mediator of the prospective relationship between fear of abandonment, as assessed at Times 1-3, and youth's reports of depression as assessed at six-year follow-up, a plausible alternative model is that depression mediates the relationship between fear of abandonment and romantic attachment anxiety. We tested this alternative model and found that the a path from fear of abandonment at Times 1-3 to depressive symptoms at six-year follow-up was not significant (β = .92, p =.45), but the b path between concurrent depression and romantic attachment anxiety at six-year follow-up was significant (β = .12, p = 0.00). The confidence interval for the mediated effect included zero, indicating that mediation was not present.

The interactions of age and gender with fear of abandonment were not significant in predicting the mediators at six-year follow-up or in predicting youth's reports of depressive symptoms at the six-year follow-up. However, the interaction of age with caregiver attachment at the six-year follow-up predicted caregivers’ reports of depressive symptoms at the six-year follow-up (β = .50, p = .02). The relationship of caregiver attachment to concurrent caregiver reports of depressive symptoms at six years was significant for younger but not older participants.

Because the social relationship variables that were tested as mediators were intercorrelated, a post-hoc analysis explored which of these variables predicted depression over and above their shared variance. All mediators were entered in a simultaneous regression to predict depressive symptoms at six-year follow-up, controlling for depression at Time 1, age, gender and the composite of fear of abandonment at Times 1-3. Romantic attachment anxiety (β = −2.03, p < .01) and peer competence (β =.61, p = .01) assessed at the six-year follow-up were associated with youth's and young adults’ reports of depressive symptoms over and above the other social relationship variables. No mediator significantly predicted caregiver reports of depressive symptoms over and above the other mediators.

Discussion

Studies of children who have experienced family disruptions have found that fears of being abandoned by a caregiver are associated with the development of children's mental health problems (Wolchik et al., 2006; Wolchik et al., 2002). However, no prior research has investigated the pathway by which these fears of abandonment lead to mental health problems of children who have experienced these family stressors. One potential pathway derived from developmental literature is that youth's fears of abandonment by caregivers affect the quality of their later social relationships with caregivers, peers, and romantic partners in adolescence and young adulthood, which then affect the development of mental health problems such as depression. Parentally-bereaved youth are a particularly interesting population in which to study these relationships because they are likely to have heightened fears of abandonment and are at increased risk of developing depressive symptoms.

The current study tested whether youth's fears of abandonment following the death of a parent led to later depressive symptoms by influencing the youth's relationships with caregivers, peers, and romantic partners. The results indicated that youth's fears of abandonment in childhood/adolescence were related to their anxiety in romantic relationships during adolescence/early adulthood, which was, in turn, associated with their depressive symptoms during adolescence/young adulthood. The results also indicated that adolescents and young adults who reported higher-quality relationships with their peers, romantic partners and caregivers had fewer depressive symptoms as reported by both the youth and their caregivers. The relationship between adolescents’/young adults’ attachment to their caregiver and their caregiver's reports of the youth's depressive symptoms was stronger for younger than for older participants. These findings contribute to the understanding of mental health processes in parentally-bereaved children, an understudied population.

The most important finding of the study is the significant longitudinal pathway from youth's fear of abandonment during childhood/adolescence to higher levels of anxiety in romantic relationships six years later, in adolescence/young adulthood, which, in turn, were associated with higher levels of concurrent self-reports of symptoms of depression. Although prior studies have found significant prospective pathways from insecure relationship with parents and symptoms of depression in adolescence or early adulthood (e.g. Armsden & Greenberg, 1990; Margolese, Markiewicz, & Doyle, 2005), this is the first study to find that romantic attachment anxiety mediates the prospective relationships between youth's fear of abandonment and their depressive symptoms in adolescence/early adulthood. Although the causal direction of the path between romantic attachment anxiety and depressive symptoms cannot be definitively established because the variables were assessed concurrently, it is notable that a test of the alternative meditational pathway of depression mediating the relationship between youth's fear of abandonment and their romantic anxiety was not significant.

In a retrospective study of parentally-bereaved youth, Harris, Brown, and Bifulco (1990) found evidence that bereaved girls seek out unhealthy romantic relationships because of a lack of parental care in the home following parental death, and that the unhealthy romantic relationship are part of a cascade of events leading to depression in early adulthood. The finding of the prospective half-longitudinal design is consistent with this model, showing that children and adolescents’ fears that their caregiver might abandon them predicted insecure romantic relationships six years later. The current study broadens Harris and colleagues’ model by finding that this prospective relationship was not different between boys and girls. Attachment theory proposes that children will experience continuity in attachment working models across development and relationships (Bowlby, 1969; 1982). Because fear of abandonment can be conceptualized as related to anxious attachment to a caregiver, our finding lends support for the continuity of attachment-related beliefs from parental to romantic relationships. However, the measure of fear of abandonment in the current study does not fully encompass the construct of attachment. Further research with an established measure of attachment is an important direction for future work.

A second important finding is that youth's social relationships in multiple domains (romantic, peer, caregiver) were related to concurrent depressive symptoms as rated by both caregivers and youth/young adults. Motivation theory asserts that social relationships are one of children's primary needs for adaptation following trauma and parental bereavement (e.g. Sandler, Wolchik & Ayers, 2008), and attachment theory asserts that insecure relationships increase the likelihood of depression (e.g. Armsden et al., 1990; Muris et al., 2001). Similarly, the finding that poor competence in interacting with peers in adolescence and early adulthood was related to concurrent depressive symptoms is consistent with literature linking low levels of competence to mental health problems, either by “cascading” into failures in other domains (Masten et al., 2006) or by eliciting negative social feedback (Cole, 1991). The current study augments prior literature by demonstrating that youth's anxious attachment to a romantic partner and competence in interacting with peers predicted their reports of depressive symptoms over and above their secure attachment to their caregiver and their avoidance of attachment in romantic relationships. The unique effects of romantic anxiety and peer competence on depressive symptoms may reflect the developmental salience of romantic and peer relationships during adolescence and early adulthood.

The effect of youth's attachment to their surviving caregiver on caregivers’ reports of their adolescent or young adult's depressive symptoms was stronger for younger adolescents than for older adolescents and young adults. This finding is consistent with literature on the declining dependency and closeness in parental relationships in adolescence as peer and romantic relationship become more salient (e.g. Collins & Laursen, 2004; Laursen & Williams, 1997). However, it was surprising that the effect was only found for caregivers’ reports of youth's depressive symptoms. One explanation is that younger adolescents are likely to have more contact as well as more conflicts with caregivers due to living at home and being subject to the authority of their caregiver. Caregivers observe a relatively limited sample of adolescent behavior on which to base ratings of depressive symptoms, and their ratings may largely reflect the negativity they see in their interactions with the adolescent. Adolescents’ reports of their depressive symptoms are based on behaviors across a variety of contexts and relationships, and may reflect a greater contribution of interactions and feelings they have in those other contexts.

Several limiting factors in the current study need to be noted. One limitation is the five-year time lag between the measure of fear of abandonment and the measures of social relationships with peers, romantic partners and caregivers. Little is known about the optimal time lag to test the relationships between youth's security in relationships with caregivers and their relationships with peers, romantic partners and caregivers in subsequent developmental stages. Additional research that uses other time lags would be useful. A second limitation is the use of a half-longitudinal versus full longitudinal design. Testing fully prospective mediational models in which fear of abandonment, the social relationship variables, and depressive symptoms are measured at different time points is an important direction for future research. A third limitation is that youth and young adults provided reports of all the variables except caregivers’ reports of the youth's depressive symptoms. Future research should also assess the social relationship variables using reports from peers, romantic partners, and caregivers. A final limitation involves the number of models tested. A significant mediated effect was found for one of the eight models tested, and the possibility of alpha inflation arising from testing multiple models must be acknowledged. Replication with other bereaved samples will be important to strengthen confidence in the robustness of the finding, and replication in other at-risk samples is needed to examine the generalizability of the findings.

The findings of this study contribute to existing knowledge about the role of social relationships in the development of mental health problems in adolescence and young adulthood. The results indicate that, for parentally-bereaved youth who experienced a major disruption in close relationships in childhood or adolesence, the security of their relationship with their surviving caregiver has implications for the quality of their romantic relationships and their mental health in the next developmental stage. The findings also have implications for the development of interventions to prevent long-term mental health problems for bereaved youth. The findings indicate that interventions that reduce youth's fear of abandonment (i.e. strengthen positive relationship with caregivers) following a loss may improve the quality of their social relationships and reduce depressive symptoms later in life.

References

- Achenbach TM. The child behavior profile: I. boys aged 6-11. Journal of consulting and clinical psychology. 1978;46:478–488. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.46.3.478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach TM, Dumenci L. Advances in empirically based assessment: Revised cross-informant syndromes and new DSM-oriented scales for the CBCL, YSR, and TRF: Comment on Lengua, Sadowski, Friedrich, and Fisher (2001). Journal of consulting and clinical psychology. 2001;69:699–702. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach TM, Edelbrock CS. The child behavior profile: II. boys aged 12-16 and girls aged 6-11 and 12-16. Journal of consulting and clinical psychology. 1979;47(2):223–233. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.47.2.223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach TM, Dumenci L, Rescorla LA. DSM-oriented and empirically based approaches to constructing scales from the same item pools. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2003;32(3):328–340. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3203_02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach TM. Manual for the Young Adult Self-Report and Young Adult Behavior Checklist. University of Vermont, Department of Psychiatry; Burlington, VT: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach TM. Manual for the Youth Self-Report and 1991 Profile. University of Vermont, Department of Psychology; Burlington, VT: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Armsden GC, Greenberg MT. The Inventory of Parent and Peer Attachment: Individual differences and their relationship to psychological well-being in adolescence. Journal of Youth & Adolescence. 1987;16:427–454. doi: 10.1007/BF02202939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armsden GC, McCauley E, Greenberg MT, Burke PM, Mitchell JR. Parent and peer attachment in early adolescent depression. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1990;18:683–697. doi: 10.1007/BF01342754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1986;51:1173–1182. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohlin G, Hagekull B, Rydell A. Attachment and social functioning: A longitudinal study from infancy to middle childhood. Social Development. 2000;9:24–39. [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby J. Attachment and loss: Vol. 1 Attachment. Basic Books; New York: 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby J. Attachment and loss: Vol. 3 Loss, Sadness, and Depression. Basic Books; New York: 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby J. Attachment and loss: Retrospect and prospect. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 1982;52(4):664–678. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-0025.1982.tb01456.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brennan KA, Clark CL, Shaver PR. Self-report measurement of adult attachment. In: Simpson JA, Rholes WS, editors. Attachment theory and close relationships. Guilford Press; New York: 1998. pp. 46–76. [Google Scholar]

- Brennan KA. Dec, 2001. personal communication.

- Burt KB, Obradovic J, Long JD, Masten AS. The interplay of social competence and psychopathology over 20 years: Testing transactional and cascade models. Child Development. 2008;79:359–374. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.01130.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cantwell DP, Lewinsohn P, Rohde P, Seeley J. Correspondence between adolescent report and parent report of psychiatric diagnostic data. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 1997;36(5):610–619. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199705000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cerel J, Fristad MA, Verducci J, Weller RA, Weller EB. Childhood bereavement: Psychopathology in the 2 years postparental death. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2006;45(6):681–690. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000215327.58799.05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coatsworth D, Sandler IN. Multi-rater measurement of competence in children of divorce.. Paper presented at the biennial conference of the Society for Community Research and Action; Williamsburg, VA. 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Lawrence Erlbaum Assoc.; Hillsdale, NJ: 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Cole DA. Preliminary support for a competency-based model of depression in children. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1991;100(2):181–190. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.100.2.181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole DA, Martin JM, Powers B, Truglio R. Modeling causal relations between academic and social competence and depression: A multitrait-multimethod longitudinal study of children. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1996;105(2):258–270. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.105.2.258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole DA, Maxwell SE. Testing mediational models with longitudinal data: Questions and tips in the use of structural equation modeling. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2003;112:558–577. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.112.4.558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins N, Read S. Adult attachment, working models, and relationship quality in dating couples. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology. 1990;58:644–663. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.58.4.644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins NL, Guichard AC, Ford MB, Feeney BC. Working models of attachment: New developments and emerging themes. In: Rholes WS, Simpson JA, editors. Adult attachment: Theory, research, and clinical implications. Guilford Publications; New York, NY, US: 2004. pp. 196–239. [Google Scholar]

- Collins WA, Laursen B. Parent-Adolescent relationships and influences. In: Steinberg LD, editor. Handbook of Adolescent Psychology. Wiley; New Jersey: 2004. pp. 331–355. 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Cook WL. Understanding attachment security in family context. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2000;78:285–294. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.78.2.285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cotterell JL. The relation of attachments and support to adolescent well-being and school adjustment. Journal of Adolescent Research. 1992;7(1):28–42. [Google Scholar]

- Cyranowski JM, Frank E, Young E, Shear K. Adolescent onset of the gender difference in lifetime rates of major depression. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2000;57(1):21–27. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.57.1.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harter S. The perceived competence scale for children. Child Development. 1982;53:87–97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris T, Brown GW, Bifulco AT. Loss of parent in childhood and adult psychiatric disorder: A tentative overall model. Development and psychopathology. 1990;2:311–328. [Google Scholar]

- Hazan C, Shaver PR. Romantic love conceptualized as an attachment process. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1987;52:511–524. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.52.3.511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofer MA. Relationships as regulators: A psychobiologic perspective on bereavement. Psychosomatic medicine. 1984;46:183–197. doi: 10.1097/00006842-198405000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen PS, Rubio-Stipec M, Canino G, Bird HR, Dulcan MK, Schwab-Stone ME, Lahey BB. Parent and child contributions to diagnosis of mental disorder: Are both informants always necessary? Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 1999;38(12):1569–1579. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199912000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenny DA, Zautra A. The trait-state-error model for multiwave data. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1995;63(1):52–59. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.63.1.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendler KS, Sheth K, Gardner CO, Prescott CA. Childhood parental loss and risk for first-onset of major depression and alcohol dependence: The time-decay of risk and sex differences. Psychological Medicine. 2002;32:1187–1194. doi: 10.1017/s0033291702006219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerns KA, Klepac L, Cole A. Peer relationships and preadolescents’ perceptions of security in the child-mother relationship. Developmental psychology. 1996;32:457–466. [Google Scholar]

- Kovacs M. Rating scales to assess depression in school-aged children. ActaPaedopsychiatrica: International Journal of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 1981;46:305–315. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurdek LA, Berg B. Children's beliefs about parental divorce scale: Psychometric characteristics and concurrent validity. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology.Special Issue: Eating disorders. 1987;55:712–718. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.55.5.712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ladd GW. Children's peer relations and social competence: A century of progress. Yale University Press; New Haven, CT: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Laursen B, Williams V. Perceptions of interdependence and closeness in family and peer relationships among adolescents with and without romantic partners. In: Shulman S, Collins W, editors. Romantic relationships in adolescence: Developmental perspectives. Jossey-Bass; San Francisco, CA: 1997. pp. 3–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leadbeater BJ, Kuperminc GP, Blatt SJ, Hertzog C. A multivariate model of gender differences in adolescents’ internalizing and externalizing problems. Developmental Psychology. 1999;35:1268–1282. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.35.5.1268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lieberman M, Doyle AB, Markiewicz D. Developmental patterns in security of attachment to mother and father in late childhood and early adolescence: Associations with peer relations. Child Development. 1999;70:202–213. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Dwyer JH. Estimating mediated effects in prevention studies. Evaluation Review. 1993;17:144–158. [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Fritz MS, Williams J, Lockwood CM. Distribution of the product confidence limits for the indirect effect: Program PRODLIN. Behavior Research Methods. 2007;39:384–389. doi: 10.3758/bf03193007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP. Introduction to Statistical Mediation Analysis. Lawrence Erlbaum; New York, NY: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Main M, Kaplan N, Cassidy J. Security in infancy, childhood, and adulthood: A move to the level of representation. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development. 1985;50:66–104. [Google Scholar]

- Margolese SK, Markiewicz D, Doyle AB. Attachment to parents, best friend, and romantic partner: Predicting different pathways to depression in adolescence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2005;34:637–650. [Google Scholar]

- Masten AS, Coatsworth JD. The development of competence in favorable and unfavorable environments: Lessons from research on successful children. American Psychologist. 1998;53:205–220. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.53.2.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masten A, Roisman GI, Long JD, Burt K, Obradovic J, Riley JR, et al. Developmental cascades: Linking academic achievement, externalizing and internalizing symptoms over 20 years. Developmental Psychology. 2005;41:733–746. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.41.5.733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayseless O, Scharf M. Adolescents’ attachment representations and their capacity for intimacy in close relationships. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2007;17:23–50. [Google Scholar]

- Melhem NM, Moritz G, Walker M, Shear MK, Brent D. Phenomenology and correlates of complicated grief in children and adolescents. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2007;46:493–499. doi: 10.1097/chi.0b013e31803062a9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mikulincer M, Florian V. Exploring individual differences in reactions to mortality salience: Does attachment style regulate terror management mechanisms? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2000;79:260–273. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.79.2.260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muris P, Meesters C, van Melick M, Zwambag L. Self-reported attachment style, attachment quality, and symptoms of anxiety and depression in young adolescents. Personality and Individual Differences. 2001;30:809–818. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén MO. Mplus user's guide. Muthén & Muthén; Los Angeles, CA: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Petraitis J, Flay BR, Miller TQ. Reviewing theories of adolescent substance use: Organizing pieces in the puzzle. Psychological Bulletin. 1995;117:67–86. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.117.1.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinherz HZ, Giaconia RM, Hauf AMC, Wasserman MS, Silverman AB. Major depression in the transition to adulthood: Risks and impairments. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1999;108:500–510. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.108.3.500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roisman GI, Madsen SD, Hennighausen KH, Sroufe LA, Collins WA. The coherence of dyadic behavior across parent–child and romantic relationships as mediated by the internalized representation of experience. Attachment & Human Development. 2001;3:156–172. doi: 10.1080/14616730126483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudolph KD, Flynn M. Childhood adversity and youth depression: Influence of gender and pubertal status. Development and Psychopathology. 2007;19:497–521. doi: 10.1017/S0954579407070241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudolph KD, Lambert SF. Child and Adolescent Depression. In: Marsh EJ, Barkley RA, editors. Assessment of Childhood Disorders. 4th Edition The Guilford Press; New York: 2007. pp. 213–252. [Google Scholar]

- Sandler IN. Quality and ecology of adversity as common mediators of risk and resilience. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2001;29:19–63. doi: 10.1023/A:1005237110505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandler IN, Ayers TS, Wolchik SA, Tein J, Kwok O, Haine RA, et al. The family bereavement program: Efficacy evaluation of a theory-based prevention program for parentally bereaved children and adolescents. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2003;71:587–600. doi: 10.1037/0022-006x.71.3.587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandler I, Wolchik S, Ayers T. Resilience rather than recovery: A contextual framework on adaptation following bereavement. Death Studies. 2008;32:59–73. doi: 10.1080/07481180701741343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schafer JL, Graham JW. Missing data: Our view of the state of the art. Psychological Methods. 2002;7:147–177. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaver P. Jun 27, 2005. personal communication.

- Skinner EA, Wellborn JG. Coping during childhood and adolescence: A motivational perspective. In: Featherman DL, Lerner RM, Perlmutter M, editors. Life-span development and behavior. Vol. 12. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.; Hillsdale, NJ, England: 1994. pp. 91–133. [Google Scholar]

- Skinner EA, Wellborn JG. Children's coping in the academic domain. In: Wolchik SA, Sandler IN, editors. Handbook of children's coping: Linking theory and intervention. Plenum Press; New York, NY, US: 1997. pp. 387–422. [Google Scholar]

- Sobel J. Asymptotic confidence intervals for indireccct effects in structural equation models. In: Leinhardt S, editor. Sociological methodology 1982. Jossey Bass; San Francisco: 1982. pp. 290–312. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Bureau Census . One-parent family groups with own children under 18, by marital status, and race and Hispanic origin of the reference person. Washington, DC: 2001. pp. 20–537. [Google Scholar]

- van Lang NDJ, Ferdinand RF, Oldehinkel AJ, Ormel J, Verhulst FC. Concurrent validity of the DSM-IV scales affective problems and anxiety problems of the youth self-report. Behaviour research and therapy. 2005;43(11):1485–1494. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2004.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West SG, Finch JF, Curran PJ. Structural equation models with nonnormal variables: Problems and remedies. In: Hoyle RH, editor. Structural equation modeling: Concepts, issues, and applications. Sage Publications, Inc.; Thousand Oaks, CA, US: 1995. pp. 56–75. [Google Scholar]

- Williams NL, Risking JH. Adult romantic attachment and cognitive vulnerabilities to anxiety and depression: Examining the interpersonal basis of vulnerability models. Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy. 2004;18(1):7–24. [Google Scholar]

- Wolchik SA, Ma Y, Tein J, Sandler IN, Ayers TS. Parentally bereaved children's grief: Self-system beliefs as mediators of the relations between grief and stressors and caregiver-child relationship quality. Death Studies. 2008;32(7):597–620. doi: 10.1080/07481180802215551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolchik SA, Tein J, Sandler I, Ayers T. Self-system beliefs as mediators of the relations of stressors and caregiver–child relationship quality with children's adjustment problems after parental death. 2005. Unpublished manuscript. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Wolchik SA, Tein J-Y, Sandler I, Ayers RS. Stressors, quality of child-caregiver relationship, and children's mental health problems after parental death: the mediating role of self-system beliefs. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2006 doi: 10.1007/s10802-005-9016-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolchik SA, Tein J-Y, Sandler IN, Doyle KW. Fear of abandonment as a mediator of the relations between divorce stressors and mother-child relationship quality and children's adjustment problems. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2002;30:401–418. doi: 10.1023/a:1015722109114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Worden JW, Silverman PR. Parental death and the adjustment of school-age children. Omega: Journal of Death and Dying. 1996;33(2):91–102. [Google Scholar]