Abstract

The AIDS-related activities of religious leaders in Africa extend far beyond preaching about sexual mortality. This study aims to quantify the involvement of religious leaders in the fight against AIDS and to identify key predictors of the types of prevention strategies they promote. Using data from a random sample of Christian and Muslim leaders in Malawi, I use logistic regression to predict six types of AIDS activities, which correspond to three distinct types: formal messages (i.e., preaching), pragmatic interventions (monitoring the sexual behaviour of members and advising divorce to avoid infection), and the promotion of biomedical prevention strategies (promoting condom use and testing for HIV). Preaching about AIDS is the most common prevention activity, and promoting condom use is the least; sizable proportions of clergy promote testing and engage in pragmatic interventions. Denominational patterns in the type of engagement are weak and inconsistent. However, inquiries into the motivation for leaders' activities show that discussions with members about AIDS is the most consistent predictor, suggesting that religious leaders' engagement with HIV prevention is primarily a demand-driven phenomenon.

Keywords: HIV/AIDS, sub-Saharan Africa, religion, prevention, sexual behaviour

Introduction

Epidemiologists, public health experts, sociologists, anthropologists, and demographers continue to mine Uganda's and Senegal's early successes in reducing HIV prevalence for ideas on how to curb the spread of AIDS in other parts of sub-Saharan Africa (SSA). Several scholars have identified the early involvement of religious leaders in both countries' efforts to combat AIDS as a particularly important—and replicable—factor in their success (Green 2003, Liebowitz and Noll 2006). During the past decade, national and international efforts to address AIDS in Africa have prioritised the integration of faith-based organizations (FBOs) in their efforts to promote behaviour change and to arrest climbing prevalence rates across the sub-continent. Indeed, as trusted and influential individuals, religious leaders are well positioned to spread prevention messages and encourage behaviour change (Green 2003, UNAIDS 1999). Among dozens of other secular health NGOs, UNAIDS (Lux and Greenaway 2006), Population Services International (PSI) (Population Services International and AIDSMark 2007), UNICEF (UNICEF 2003), the World Health Organisation (AHARP for the World Health Organisation 2006), and the Global Fund (Summers 2002) have not only issued reports on religious leaders' underutilised potential in the fight against AIDS, but they have also implemented formalised programmes and curricula to educate religious leaders about AIDS and increase their involvement in the fight against its spread.

These calls to leverage religious leaders' influence and community standing in the fight against AIDS are supported empirically. Religious leaders are an important resource for many lay Africans, and their messages about sex and morality carry a great deal of weight. In Nigeria, women call upon religious leaders to address their husbands' infidelities (Smith 2009). A recent study of sexual behaviour in Malawi shows that members of congregations with leaders actively engaged in the epidemic have higher levels of adherence to the ABCs of HIV prevention (abstain, be faithful, use condoms) (Trinitapoli 2009). Furthermore, leaders and congregations are important sources of material and social support for people living with HIV and AIDS. A study of HIV-positive Congolese women emphasises the central role that faith plays in living and coping with AIDS (Maman et al. 2009). In addition to relying on prayer, these women frequently consult their religious leaders for advice and support as they make decisions about disclosing their status to family and community members. Similarly, Bazant and Boulay (2007) show that religious congregations in Ghana are an important source of material and social support for people living with HIV and AIDS, and that having heard about AIDS from religious leaders positively predicts the provision of such support.

Research on the activities and impact of religious organisations on the AIDS epidemic have been largely speculative, either focusing on what religious organisations have the potential to do, given a sufficient resource base, or highlighting the activities of a particular engaged congregation that may or may not be representative of its broader context (Epstein 2007, Green 2003a, Green 2003b, Tearfund 2006, USAID and Family Health International 2002, ). A systematic study of the content of messages in rural Malawian religious services documented explicit references to HIV and AIDS in over 30% of the religious services observed, and frequent messages about sexual morality (Trinitapoli 2006). But overall, very little is known about the extent of religious involvement in AIDS-related issues in African countries.

The existing research on the role of religion in HIV prevention in SSA reveals an important duality. On one hand, religious beliefs and practices are thought to govern the sexual behaviour of individuals, thereby lowering their risk of infection. Evidence from Zimbabwe (Gregson et al. 1999), Malawi (Trintapoli and Regnerus 2006), and South Africa (Garner 2000) reveals that risky sexual behaviour is less prevalent among members of strict religious minority groups and among those reporting high levels of religious commitment overall (Agha et al. 2006, Trintapoli and Regnerus 2006). On the other hand, consistent with findings on religion and sexual behaviour elsewhere in the world, several studies show that religious individuals in Africa are less likely to use condoms when they do engage in risky sexual behaviour, thereby increasing their risk of infection (Hill et al. 2004, Bearman and Brückner 2001, Regnerus 2007). Importantly, religion may not always be an impediment to condom use. A recent examination of the meaning of condom use in Malawi documents a host of objections but finds no evidence that religion impedes condom use (Tavory and Swidler 2009). Furthermore, lay people whose religious leaders accept condoms are significantly more likely to report using condoms themselves (Trinitapoli 2009).

The extent to which, and the ways in which, religious leaders engage in the fight against AIDS varies considerably. Possible motivational factors must be established in order to better understand this variation. As members of the community, religious leaders might perceive the seriousness of the AIDS epidemic and take steps of their own to address it. They see neighbours and congregation members getting sick, they regularly attend funerals, mourn their dead, and decide to do something about it. This could take the form of preaching more often (and more intensely) about sexual behaviour, or of deviating from an official prohibition on condom use to achieve the pragmatic goal of curbing infection.

In addition to being moved by their own perceptions, religious leaders who are involved in the fight against AIDS may be responding to demand from congregation members for leadership on the issue. Using the example from Smith (2009), women may bring concerns about their husbands' sexual behaviour to her leader for help and advice. Similarly, men may ask religious leaders for encouragement to maintain their commitments to fidelity (Watkins 2004). Leaders responding to demand from members may also intensify their preaching on related topics; they may use their leadership roles to counsel members individually; and they may also respond to demand from members for flexibility on issues like condom use and divorce in the interest of limiting the spread of AIDS.

Programmatic efforts to integrate religious leaders in the fight against AIDS may also successfully motivate religious leaders to be engaged—and to do so in different ways. Religious leaders who have had the opportunity to participate in a workshop about AIDS may come away with more accurate understandings about the disease and a more expansive skill-set for promoting prevention in their communities. The curricula used to educate and involve religious leaders encourage them to promote accurate messages about transmission and prevention, to speak out on AIDS, to avoid condemnation, and to provide love and support for infected members (UNICEF 2003). These curricula also highlight biomedical prevention methods like condom use and the importance of knowing one's status, and may translate into higher engagement with these types of prevention efforts, as well as more frequent preaching about AIDS and sexual morality.

While the importance of involving African religious leaders in HIV prevention has been established, estimations of their contributions will remain speculative until they are documented both numerically and substantively. This study contributes by a) quantifying the AIDS-related activities of religious leaders in Malawi and b) indentifying key predictors of the AIDS-related prevention activities in which they engage. In other words, this study develops an articulation of what religious leaders are doing about AIDS, and what motivates them to take a hands-on approach to addressing the epidemic in their communities. Though I focus exclusively on the role of religious leaders in prevention messages, I acknowledge that the scope of this paper does not encompass the roles of religious leaders who, along with their congregations, are relevant to other aspects of the AIDS epidemic, like disclosure (Maman et al. 2009), treatment, and caregiving (Agadjanian and Menjivar 2008, Bazant and Boulay 2007).

Setting and methods

The Malawian setting is ideal for exploring the question of what religious leaders do to prevent the spread of AIDS and what factors are associated with these activities. The most recent national prevalence estimates puts adult prevalence at 14%, and recent research suggests that the epidemic is stabilising, due to widespread behaviour change and increased access to anti-retroviral therapy, particularly for pregnant women (UNAIDS 2007). In addition to featuring a stabilising generalised epidemic, Malawi is one of the most religiously diverse countries in Africa, with sizable Muslim, Pentecostal, Catholic, and Protestant populations, as well as members of indigenous churches (World Christian encyclopedia: A comparative survey of churches and religions in the modern world 2001). This religious diversity offers an opportunity to assess the magnitude of differences by tradition and establish cross-cutting factors that facilitate or impede religious leaders' involvement irrespective of denomination.

The data for this study come from the Malawi Religion Project (MRP), a multi-method study of religious congregations and their institutional responses to HIV in the context of a generalised AIDS epidemic, conducted in three religiously and ethnically distinct districts: the Rumphi district in the North, Balaka in the South, and Mchinji in the Central region. The MRP used a hypernetwork sampling approach; the principle behind hypernetwork sampling is that asking a random sample of individuals to list the organisations to which they belong produces a random sample of organisations (McPherson 1982). This is particularly useful in cases from which there is no universe from which to draw a sample—a common problem for the study of organizations generally, and religious congregations in particular (Chaves et al. 1999), especially in the developing world.

In this case, the MRP is a sister-project to the Malawi Diffusion and Ideational Change Project (MDICP), an ongoing longitudinal study of ever-married women and their husbands that began in 1998 but added a sample of adolescents in 2004. The MDICP focuses on attitudes about family planning and AIDS in a rural context (Social Networks 2006). The MDICP was not designed to be a nationally representative sample, but comparisons with rural respondents from Malawi's Demographic and Health Surveys (MDHS) showed that the MDICP sample in 2004 was comparable to a national survey on all key socio-demographic characteristics (e.g., gender, age, education, ethnicity, marital status) (Anglewicz et al. 2009).

In 2004, all MDICP respondents were asked to name the religious congregation they attend; only 3% of respondents failed to name a congregation or reported that they do not attend. In 2005, the MRP team identified the leaders of each of the 187 congregations named by the MDICP's 3,254 respondents and conducted both an in-depth interview and brief survey with these congregational representatives—in most cases the respondent was a priest, a pastor, or a sheik; in a limited number of cases (N=4) the respondent was a church secretary or treasurer. MRP respondents were overwhelmingly male; only nine congregations (less than 5%) were led by women. Leaders were asked about their formal messages on the subject of AIDS and sexual behaviour as well as other types of advice and activities they provide to members. The questionnaire also included a series of questions about their attitudes about AIDS, family life, the impact of AIDS on the congregation and the community, and their relationships to other community leaders.

Data collection and analysis was supported by a grant from the US government's National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. The funding source had no role in the study design; in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; or in the writing of this report.

Dependent Variables

Speaking Out on AIDS

Leaders were asked about the frequency with which they discuss a number of topics during their weekly religious services. Topics include: morality generally, sexual morality in particular, HIV, illness, death and the afterlife, and politics. I use the reports of the leaders to distinguish those who talk explicitly about AIDS on a regular basis (every week or almost every week) from those who do not. In addition, I separately examine leaders who give frequent (weekly) messages about sexual morality.

Pragmatic Interventions

In addition to addressing entire congregations though preaching, religious leaders also give targeted advice to particular members they perceive to be at high risk for contracting HIV. Based on the collection of qualitative data during a pilot project preceding the collection of MRP data, I identified two forms of pragmatic interventions religious leaders practise: privately advising/admonishing members to stop promiscuity and advising members to get a divorce in order to avoid being infected with HIV by their spouse.

While admonishing against promiscuous behaviour falls within a traditional theme for religious leaders across religious traditions, the MRP qualitative data reveal that the methods rural Malawian religious leaders use are unique—direct interventions in the sex-lives of their members. Many religious leaders hang around outside bars to “catch” members (particularly men) who might be looking for sexual partners, and make unsolicited visits to couples in their homes to counsel them about the importance of fidelity in the context of AIDS (Trinitapoli 2009). Nearly all of the religious leaders in the MRP (98%) reported privately advising members to stop promiscuity during the past year using the methods described above; I label those who engage in this activity on a weekly basis as engaged in “monitoring” the sexual behaviour of their members in order to prevent the further spread of AIDS in their communities. These leaders make a habit of watching to see what happens and doing something about it in the form of an intervention.

Recently, scholars have pointed to liberalisation of attitudes towards divorce in SSA as an indicator that individuals are using divorce as a strategy for avoiding HIV infection (Reniers 2008, Smith and Watkins 2005). Religious leaders who, during the past year, have urged a member to leave a spouse or get a divorce in order to avoid being infected with HIV are coded 1 for endorsing divorce as an acceptable prevention strategy.

Biomedical Prevention Messages

Religious leaders may give advice that reinforces or that contradicts the prevention messages articulated by the government, international NGOs, and local health organisations. In reporting on the type of private advice they have given to members during the past year, I distinguish those who have a) privately advised members to use condoms or b) encouraged members to go for HIV testing and counselling (HTC) from those who have not.

Independent Variables

Denomination

To both examine and account for doctrinal differences in AIDS-related teachings and practices, I categorise congregations into a set of six denominational traditions using a set of dummy variables: Catholic, Mission Protestant (i.e., Anglican and Presbyterian), Pentecostal, African Independent Churches (AICs), New Mission Protestant congregations (e.g., Jehovah's Witness, Seventh Day Adventist), and Muslim.

Motivating Factors

I use three measures to examine factors that may prompt and shape the nature of a religious leader's AIDS-related activities. First, I examine the leader's perception of the seriousness of AIDS in the congregation, using the following question: “Compared with other problems your congregation faces, how big of a problem is AIDS currently?” 0=Not a problem at all, 1=somewhat of a problem, 2=big problem, 3=the single biggest problem. Second, I measure the extent to which members speak to the leader about AIDS (0=never, 1=seldom, 2=about monthly, 3=almost every week, 4=every week). Finally, I use a dummy variable to distinguish leaders who have ever attended an AIDS workshop from those who have not.

Religious Leaders' Characteristics

To test for differences that may be attributable to leaders themselves, I control for the religious leader's age and level of education. Since levels of education are low among leaders in the sample, I use a dummy variable to indicate that the respondent attended at least some secondary school.

Congregational Factors

In addition to controlling for congregational size, I employ a dummy variable to distinguish “isolated” congregations—those that have never been visited by a denominational authority, missionary, or government official—from others.

Analytic Approach

After providing an overview of the AIDS-related prevention activities of religious leaders, I examine denominational differences in these activities and assess the relationship between motivational factors and prevention activities at the bivariate level. I proceed by presenting multivariate analyses that assess associations with the three possible motivational factors discussed above, net of denominational differences, leader characteristics, and congregational factors.

Findings

Table 1 summarises the AIDS-related activities of religious leaders in rural Malawi. Not surprisingly, the most common way that religious leaders engage the AIDS epidemic is by preaching on the topic during regular weekly services. Seventy-two percent of all religious leaders report that they discuss AIDS explicitly from the pulpit nearly every week and a similar number report discussing sexual morality on an equally frequent basis. Pragmatic interventions are also common in rural Malawi. Nearly a third of religious leaders reports having advised a member to leave his or her spouse in order to avoid being infected, and over half report that they actively monitor the sexual behaviour of their members, giving private advice to individuals and couples on a weekly basis. The biomedical prevention messages familiar to public health scholars are also prevalent among religious leaders. Two-thirds have advised members to get tested for HIV, and just under a third have privately advised members to use condoms.

TABLE 1.

Overview of AIDS Prevention Activities and Characteristics of Religious Congregations

| DEPENDENT VARIABLES | |

|---|---|

| Speaking Out on AIDS | Mean |

| Preaches about AIDS Explicitly | 0.72 |

| Preaches about Sexual Morality | 0.73 |

| Pragmatic Interventions | |

|---|---|

| Monitors Members' Sexual Behavior | 0.52 |

| Advises Divorce | 0.32 |

| Biomedical Prevention Messages | |

|---|---|

| Promotes Condom Use | 0.27 |

| Promotes Testing for HIV | 0.66 |

| INDEPENDENT VARIABLES | |

|---|---|

| Motivating Factors | |

| Perception of AIDS Problem in Congregation (0–3) | 1.77 |

| Members Talk to Leader about HIV (0–4) | 2.34 |

| Has Attended an AIDS Workshop | 0.47 |

| Denomination | |

|---|---|

| Catholic | 0.11 |

| Pentecostal | 0.17 |

| New Mission Protestant | 0.18 |

| African Independent Church | 0.20 |

| Muslim | 0.12 |

| Mission Protestant | 0.21 |

| Congregational and Clergy Characteristics | |

|---|---|

| Congregation Size (4–370) | 37.39 |

| Isolated Congregation | 0.24 |

| Leader Age (18–88) | 48.35 |

| Some Secondary Education | 0.29 |

Source: Malawi Religion Project, 2005

Variables are dichotomouse unless otherwise noted

N=187

A mere 10% of religious leaders (N=18) do not participate in any of the AIDS-prevention activities explored here, and just 7% (N=13) report engaging in all six of these prevention efforts. A correlation matrix of all six dependent variables (not shown; available from the author upon request) shows that correlations among these activities are low overall, ranging from .37 (between messages on sexual morality and AIDS) to .07 (between monitoring sexual behaviour and promoting condoms), with the highest correlations consistently occurring between activities belonging to the same category.

The descriptive statistics also show that AIDS has a strong presence in congregational life. Religious leaders frequently discuss issues related to HIV with members—31% report that their members discuss their AIDS-related concerns with them on a weekly basis (not shown), while 25% said that AIDS was the single biggest problem facing their congregation. Efforts to engage religious leaders have been far-reaching: nearly half the religious leaders in rural Malawi have participated in an AIDS workshop, but religious leaders leading isolated congregations are significantly less likely to have participated in such a workshop (32% vs. 51%, p<.05, not shown).

The denominational breakdown of congregations in Malawi roughly approximates the country's religious composition (Trinitapoli 2009, World Christian encyclopedia: A comparative survey of churches and religions in the modern world 2001). Catholic and Muslim congregations tend to be large and are, therefore, less numerous than their proportion of the population. In contrast, AIC congregations tend to be very small, sometimes composed of only 2–3 families, and are overrepresented relative to their share of the population.

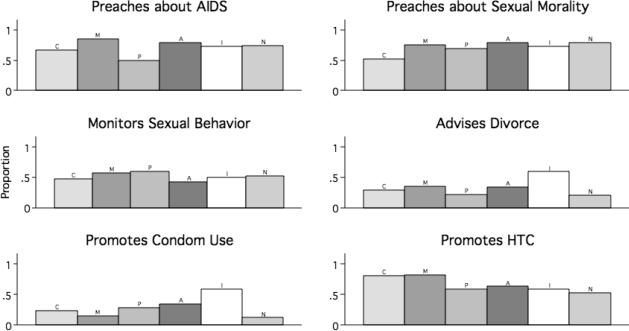

Figure 1 illustrates differences in AIDS prevention efforts by religious tradition, revealing several interesting and counter-intuitive patterns. Catholic leaders speak infrequently about sexual morality, compared with Mission Protestant, AIC, and New Mission Protestant religious leaders, while Pentecostal leaders are the least likely to talk about AIDS explicitly in weekly services. The practice of monitoring the sexual behaviour of members is distributed fairly evenly across traditions; t-tests (not shown) reveal no significant differences in this practice. Muslim leaders are most likely to advise divorce and to promote condom use among their members. Despite the Vatican's official prohibition on all forms of modern contraception, including condoms, Catholic leaders are no less likely than leaders of any group but Muslims to promote condoms among their members, suggesting that pragmatic concerns about the spread of the disease trump ideology in this context. Along with Mission Protestant leaders, Catholic leaders are also the most likely to be promoting HTC among members.

Figure 1.

AIDS Prevention Activities by Religous Tradition

Source: MRP, 2005, N=187

C=Catholic; M=Mission Protestant; P=Pentecostal; A=AIC; I=Muslim; N=New Mission Protestant

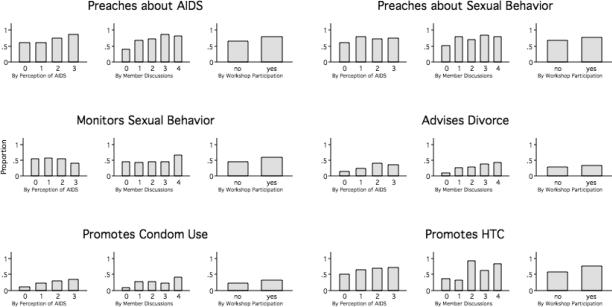

Bivariate associations between three motivational factors and AIDS-related prevention activities are presented in Figure 2. The leaders' perceptions of the AIDS problem are positively associated with explicit messages about AIDS, as well as with the promotion of condom use and HTC. The relationship of leader perceptions to messages about sexual behaviour and advising divorce are also positive but non-linear. The figure shows that associations between members discussing AIDS with their leader and prevention activities are frequently non-linear; however, this factor positively predicts all but one of the outcomes examined here (monitoring sexual behaviour of members is not significant.) The bivariate associations between having attended an AIDS workshop and participating in each type of prevention activity examined here is positive, though for only three prevention activities (preaching about AIDS, promoting HTC, and monitoring the sexual behaviour of members) are these associations statistically significant (p<.05).

Figure 2.

Examining Prevention Activities by Three Types of Motivation

Source: MRP 2005, N=187

Perception of AIDS Problem ranges from 0 (not a problem) to 3 (single biggest problem)

Member Discussions of AIDS ranges from 0 (never) to 4 (every week)

Table 2 presents adjusted odds ratios for the predictors of six types of prevention activities prevalent among religious leaders. Here, the attention shifts away from denominational differences to examine the other factors that might motivate religious leaders to engage in prevention activities: leaders' perceptions of the AIDS problem, demand from members (in the form of members discussing AIDS with their leader), and having participated in an AIDS workshop.

Table 2.

Adjusted Odds Ratios Predicting Three Types of AIDS-Prevention Activities

| Speaking Out on AIDS |

Pragmatic Interventions |

Biomedical Prevention Messages |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Preaches about Sexual Morality | Preaches about AIDS | Monitors Members' Sexual Behavior | Advises Divorce | Promotes Condoms | Promotes HTC | |

| Perception of AIDS Problem | 1.13 | 1.57* | 0.70* | 1.02 | 1.26 | 0.86 |

| Members Discuss AIDS | 1.37** | 1.58*** | 1.27* | 1.50** | 1.47* | 1.86*** |

| Attended AIDS Workshop | 1.44 | 1.59 | 1.72 | 0.94 | 2.28* | 1.48 |

| Denomination (Reference is Catholic) | ||||||

| Catholic | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Mission Protestant | 3.11 | 3.33 | 1.12 | 0.85 | 0.47 | 1.01 |

| Pentecostal | 1.93 | 0.68 | 1.32 | 0.37 | 1.32 | 0.24+ |

| AIC | 4.03* | 2.37 | 0.60 | 0.72 | 1.68 | 0.34 |

| Muslim | 5.22* | 2.32 | 1.02 | 7.70 | 7.14* | 0.20+ |

| New Mission Protestant | 4.83* | 3.05 | 0.91 | 0.43 | 0.51 | 0.15* |

Source: Malawi Religion Project, 2005

p<001

p<01

p<05

p<10

Models include controls for leaders' age, education, congregation size, and isolated congregation

N=187

Leaders whose members talk with them about their AIDS-related concerns are more likely to preach regularly about both sexual morality and AIDS from the pulpit. Not surprisingly, leaders who perceive AIDS to be a serious problem in their congregation are most likely to address it directly in weekly services. But participation in an AIDS workshop is not associated with an increase in relevant preaching. Muslim, AIC, and New Mission Protestant leaders discuss sexual morality with great frequency, while explicit messages about AIDS are distributed evenly across denominations once we account for these other factors.

Having members that discuss AIDS is a persistent predictor of every type of AIDS prevention activity examined here. In congregations where members discuss AIDS with their leaders, leaders are more likely to monitor the sexual behaviour of members, advise divorce, promote condoms, and promote HTC. Demand from members is particularly relevant for both types of pragmatic interventions, which do not vary at all by denomination.

Having attended an AIDS workshop positively predicts only one type of prevention activity among religious leaders—the promotion of condoms. Independent of denominational differences, leaders who have attended an AIDS workshop are more than twice as likely to privately advise members to use condoms than those who have never participated in one. However workshop attendance is not associated with promoting HTC. Denominational differences in the promotion of biomedical prevention strategies are immediately evident. Net of other factors, Muslim leaders are more than seven times as likely as Catholic leaders to promote condom use among their members, while Catholics are among the most likely to urge their members to go for HTC. Relatively low levels of HTC promotion among New Mission Protestant leaders is not surprising, given prohibitions against blood transfusion among Jehovah's Witnesses and the general suspicion of the medical establishment that characterises Seventh Day Adventists worldwide.

Interpretation

Religious leaders in Malawi use a variety of approaches to address the AIDS problem in their communities: they preach about it, they reinforce biomedical prevention strategies (condoms and HTC), and they also directly intervene in the private lives of their members—admonishing sexual indiscretions and encouraging divorce for members who are at risk of being infected by an unfaithful spouse. The AIDS-prevention activities of religious leaders in rural Malawi are also plentiful, with over 90% of religious leaders reporting involvement in at least one of the six prevention efforts explored here, but they vary markedly both in nature and in scope. Examining patterns in these prevention activities shows that member-driven demand for leadership on the issue of AIDS is the single most important predictor of the activities of religious leaders. Doctrinal constraints, leaders' perceptions of the AIDS problem, and formal training through workshops are secondary, motivating and prohibiting only certain types of prevention activities.

As we might expect from anecdotal evidence, the promotion of condom use is the least prevalent prevention activity among Malawian religious leaders; however, opposition to condom use is far from monolithic. Nearly a third of leaders report privately encouraging members to use condoms, including 23% of Malawi's Catholic and nearly 60% of its Muslim leaders. Since only few studies have endeavoured to understand religious reactions to condoms in this context (Pfeiffer 2004, The Lancet Editorial 2006), careful inquiries into the conditions under which religious leaders might accept or oppose condoms as a method of HIV prevention may help maximize opportunities to include them as partners in their promotion.

Unlike characterisations of religious leaders that paint them as doctrinaire ideologues in their opposition to condom use and insistence on sexual abstinence, I find that religious leaders in rural Malawi may be most aptly characterised as “public health moderates.” Though unlikely to endorse condoms as a primary means of preventing HIV, their messages about sex in the context of AIDS are quintessentially pragmatic and are closely aligned with the methods of prevention their members already find most acceptable.

Across classes of prevention strategies, the only consistent predictor of AIDS-related activities is the phenomenon of members bringing their AIDS-related concerns to their leader. Although over 50% of leaders have participated in an AIDS workshop, this experience appears to have little bearing on their likelihood of engaging in most of the prevention activities explored here. Taken together, these two pieces of evidence suggest that the AIDS-related activities of religious leaders are primarily demand-driven phenomena. Religious leaders in SSA are trusted members of their communities to whom individuals frequently turn for leadership on the questions and problems that are most salient in their lives. The AIDS epidemic is no exception. This study provides little evidence that “supply-side” efforts—NGO-sponsored workshops and formalized attempts to engage religious leaders in HIV prevention—influence the activities in which they engage.

Limitations and future directions

This study is modest in its aim to establish the nature, prevalence, and patterning of the AIDS-prevention activities of religious leaders in the heart of the AIDS-belt but is unable to establish the efficacy of leaders' various efforts. For example, are endorsements of condom use associated with higher level of uptake among members hearing such messages? Is marital fidelity actually higher among members attending congregations where the sexual behaviour of members is closely monitored? And do provisions for divorce to avoid HIV infection actually allow women to protect themselves by leaving an unfaithful spouse? The efficacy of pragmatic interventions is of particular interest, as these might be more closely aligned with cultural scripts members already find acceptable and are most likely to utilise in their continued efforts to safely navigate the epidemic.

This study examines only the prevention efforts of religious leaders, while their roles in caregiving and AIDS mitigation might be especially important. Future research should prioritise establishing better understandings of the role of religious leaders and congregations in combating AIDS in ways that extend beyond prevention.

Finally, the AIDS prevention activities of Malawian religious leaders may or may not be generalisable to other parts of the sub-continent. On one hand, Malawi is a religiously diverse country, which allows me to examine a variety of traditions in a single context. However this same religious diversity might contribute to greater religious pluralism; interacting frequently with leaders and lay people of other faiths may increase flexibility on issues like condom use and divorce, that may not be in other, more religiously homogeneous, parts of Africa. Similarly, congregational leaders in the rural Malawian setting have little oversight from denominational leaders (e.g., bishops, presidents), who may be better positioned to effectively enforce adherence to official doctrine in urban areas.

Implications for programs and policy

Future efforts to educate religious leaders about AIDS and engage them in prevention and mitigation efforts will be most effective if they are grounded in a thorough understanding of what religious leaders are already doing in their communities and why. Workshops designed to engage religious leaders in the fight against AIDS devote substantial time and space to urging religious leaders to “break the silence”—this despite the fact that preaching about AIDS and sexual morality is common practice in Malawi, and across Africa, and unlikely to rise substantially through additional training or sensitisation. This particular message may, therefore, be a futile use of time and resources.

Condom promotion is the least common prevention activity examined here, but it may have important consequences for members (Trinitapoli 2009). Patterns in religious leaders' promotion of condom use caution against assuming that denominational edicts against their use accurately indicate the position of leaders on the ground. AIDS workshops for African religious leaders may be successful in increasing the likelihood that religious leaders promote condoms among their members, but as the only measureable utility of workshops in promoting AIDS-prevention activities, this has some severe limitations. To illustrate, I applied the prevalence of condom promotion observed among religious leaders who have attended a workshop to all of those who have not, and estimated that that the level of condom promotion among religious leaders could be maximally raised to 39% through workshops alone.

Participation in workshops is not significantly associated with any other prevention activity examined here, and these are areas in which religious leaders may be most effective—by providing private counsel to their members. Most religious leaders are already doing what they do best—teaching about AIDS and privately advising members. That discussions with community members about AIDS is the most consistent predictor of engaging in AIDS-related activities points to the importance of giving careful attention to the substance and magnitude of local responses. Scholars and public health workers should not underestimate the important role of informal conversations and general social interactions for arresting the epidemic. More attention should be paid to the effectiveness of the innovative strategies (such as the encouragement of divorce for prevention) local leaders implement, independent of any training manual.

Conclusion

Religious leaders in SSA possess the ability to leverage their moral authority to prevent the spread of HIV. Their role is not limited to the duties typically associated with them: preaching about abstinence to young people and about fidelity to married persons. By making a theological case for a just divorce in a context where adultery does risk lives or by de-stigmatising participation in HTC, religious leaders have the ability to shape the prevention strategies of individuals in ways that extend far beyond abstinence, faithfulness, and condom use.

Acknowledgements

Funding for this research was provided by NIH/NICHD: Religious Organisations, Local Norms, and HIV in Africa, RO1-HD050142-01. The author wishes to thank Susan Watkins, Gregory Collins, Abdul Chilungo, Sara Yeatman, Victor Agadjanian, and the anonymous reviewers at Global Public Health for their critical feedback on earlier drafts of this paper.

References

- Agadjanian V, Menjivar C. Talking about the “Epidemic of the millenium”: Religion, informal communication, and HIV/AIDS in sub-Saharan Africa. Social Problems. 2008;55(3):301–321. [Google Scholar]

- Agha S, Hutchinson P, Kusanthan T. The effects of religious affiliation on sexual initiation and condom use in Zambia. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2006;38(5):550–555. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2005.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- AHARP for the World Health Organisation . Appreciating assets: The contribution of religion to universal access in Africa [online] ARHAP for the World Health Organisation; 2006. [[Accessed 22 January 2007]]. Available from: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/news/notes/2007/np05/en/index.html. [Google Scholar]

- Anglewicz P, Adams J, Obare F, Kohler HP, Watkins S. The Malawi Diffusion and Ideational Change Project 2004–206: Data collection, data quality, and analysis of attrition. Demographic Research. 2009;20(21):503–540. doi: 10.4054/demres.2009.20.21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bazant ES, Boulay M. Factors associated with religious congregation members' support to people living with HIV/AIDS in Kumasi, Ghana. AIDS and Behaviour. 2007;11(6):936–945. doi: 10.1007/s10461-006-9191-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bearman PS, Brückner H. Promising the future: Virginity pledges and the transition to first intercourse. American Journal of Sociology. 2001;106(4):859–912. [Google Scholar]

- Centre for Strategic and International Studies [[Accessed 22 January 2007]]; Available from: http://www.kaisernetwork.org/health_cast/uploaded_files/Globalfundbook.pdf.

- Chaves M, Konieczny ME, Beyerlein K, Barman E. The National Congregations Study: Background, methods, and selected results. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 1999;38(4):458–476. [Google Scholar]

- Epstein H. The invisible cure: Africa, the West, and the fight against AIDS. Farrar, Straus and Giroux; New York: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Garner RC. Safe sects? Dynamic religion and AIDS in South Africa. Journal of Modern African Studies. 2000;38(1):41–69. doi: 10.1017/s0022278x99003249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green EC. Faith-based organizations: Contributions to HIV prevention [online] USAID/Washington and The Synergy Project, TvT Associates; 2003a. [[Accessed 18 January 2006]]. Available from: http://www.docstoc.com/docs/677395/Faith-Based-Organizations-Contributions-to-HIV-Prevention---USAID-Health-HIVAIDS-Partnerships-Faith-Based-Organizations. [Google Scholar]

- Green EC. Rethinking AIDS prevention: Learning from successes in developing countries. Praeger Publishers; Westport, CT: 2003b. [Google Scholar]

- Gregson S, Zhuwau T, Anderson RM, Chandiwana SK. Apostles and Zionists: The influence of religion on demographic change in rural Zimbabwe. Population Studies. 1999;53(2):179–193. doi: 10.1080/00324720308084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill ZE, Cleland J, Ali MM. Religious affiliation and extramarital sex among men in Brazil. International Family Planning Perspectives. 2004;30(1):20–26. doi: 10.1363/3002004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liebowitz J, Noll S. The role of religion in educating Ugandan youth about HIV/AIDS. In: Morisky DE, editor. Overcoming AIDS: Lessons learned from Uganda. Information Age Publishing; Charlotte, NC: 2006. pp. 209–224. [Google Scholar]

- Lux S, Greenaway K. Scaling up effective partnerships: A guide to working with faith-based organizations in the response to HIV and AIDS [online] Ecumenical Advicacy Alliance; 2006. [[Accessed 21 January 2007]]. Available from: www.e-alliance.ch/hiv_faith_guide.jsp. [Google Scholar]

- Maman S, Cathcart R, Burkhardt G, Omba S, Behets F. The role of religion in HIV-positive women's disclosure experiences and coping strategies in Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of Congo. Social Science and Medicine. 2009;69(6):965–970. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.12.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McPherson JM. Hypernetwork sampling: Duality and differentiation among voluntary organizations. Social Networks. 1982;3(4):225–249. [Google Scholar]

- Pfeiffer J. Condom social marketing, Pentecostalism, and structural adjustment in Mozambique: A clash of AIDS prevention messages. Medical Anthropology Quarterly. 2004;18(1):77–103. doi: 10.1525/maq.2004.18.1.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Population Services International and AIDSMark . A decade of innovative marketing for health: Lessons learned [online] PSI; 2007. [[Accessed 4 June 2009]]. Available from: http://pdf.usaid.gov/pdf_docs/PNADL283.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Regnerus M. Forbidden fruit. Oxford University Press; New York: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Reniers G. Marital strategies for regulating exposure to HIV. Demography. 2008;45(2):417–438. doi: 10.1353/dem.0.0002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith DJ. Managing men, marriage, and modern love: Women's perspectives on intimacy and male infidelity in southeastern Nigeria. In: Cole J, Thomas LM, editors. Love in Africa. Oxford University Press; New York: 2009. pp. 157–180. [Google Scholar]

- Smith KP, Watkins SC. Perceptions of risk and strategies for prevention: Responses to HIV/AIDS in rural Malawi. Social Science & Medicine. 2005;60(3):649–660. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Social Networks [[Accessed 1 June 2007]];Sampling strategy for MDICP-1 and MDICP-2. 2006 Available from: http://www.malawi.pop.upenn.edu/Level%203/Malawi/docs/Sampling1.pdf.

- Summers T. [[Accessed 22 January 2007]];The global fund to fight AIDS, TB, and malaria challenges and opportunities: A report of the committee on resource mobilization and coordination. 2002 Available from: http://www.kaisernetwork.org/health_cast/uploaded_files/Globalfundbook.pdf.

- Tavory I, Swidler A. Condom semiotics: Meaning and condom use in rural Malawi. American Sociological Review. 2009;74(2):171–189. [Google Scholar]

- Tearfund . Faith untapped: Why churches can play a crucial role in tackling HIV and AIDS in Africa [online] Tearfund; 2006. [[Accessed 21 January 2007]]. Available from: http://www.tearfund.org/webdocs/Website/Campaigning/Policy%20and%20research/Faith%20u ntapped.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- The Lancet Editorial Condoms and the Vatican. The Lancet. 2006:367–1550. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68666-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trinitapoli J. Religious responses to AIDS in sub-Saharan Africa: An examination of religious congregations in rural Malawi. Review of Religious Research. 2006;47(3):253–270. [Google Scholar]

- Trinitapoli J. Religious teachings and influences on the abcs of HIV prevention in Malawi. Social Science and Medicine. 2009;69(2):199–209. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trinitapoli J, Regnerus M. Religion and HIV risk behaviors among married men: Initial results from a study in rural sub-Saharan Africa. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 2006;45(4):504–528. [Google Scholar]

- UNAIDS . Acting early to prevent AIDS: The case of Senegal [online] UNAIDS; 1999. [[Accessed 21 January 2007]]. Available from: http://data.unaids.org/Publications/iRC-pub04/una99-34_en.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- UNAIDS . 2007 AIDS epidemic update [online] UNAIDS; 2007. [[Accessed 21 January 2007]]. Available from: http://data.unaids.org/pub/EPISlides/2007/2007_epiupdate_en.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- UNICEF . What religious leaders can do about HIV/AIDS: Action for children and young people [online] UNICEF; 2003. [[Accessed 21 January 2007]]. Available from: http://www.unicef.org/publications/files/Religious_leaders_Aids.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- USAID. Family Health International . HIV/AIDS prevention, care and support across faith-based communities [online] FHI; 2002. [[Accessed 21 January 2007]]. Available from: http://www.fhi.org/en/HIVAIDS/pub/guide/abofaithbased.htm. [Google Scholar]

- Watkins SC. Navigating the AIDS epidemic in rural Malawi. Population and Development Review. 2004;30(4):673–705. [Google Scholar]

- World Christian encyclopedia: A comparative survey of churches and religions in the modern world. Oxford University Press; New York: 2001. [Google Scholar]