Abstract

Radical radiotherapy and surgery achieve similar cure rates in muscle invasive bladder cancer, but the choice of which treatment would be most beneficial cannot currently be predicted for individual patients. The primary aim of this study was to assess whether expression of any of a panel of DNA damage signalling proteins in tumour samples taken before irradiation could be used as a predictive marker of radiotherapy response, or rather was prognostic. Protein expression of MRE11, RAD50, NBS1, ATM and H2AX was studied by immunohistochemistry in pre-treatment tumour specimens from two cohorts of bladder cancer patients (validation cohort prospectively acquired) treated with radical radiotherapy and one cohort of cystectomy patients. In the radiotherapy test cohort (n=86), low tumour MRE11 expression was associated with worse cancer-specific survival compared with high expression (43.1% versus 68.7% 3 year cause-specific survival, p=0.012) by Kaplan Meier analysis. This was confirmed in the radiotherapy validation cohort (n=93) (43.0% versus 71.2%, p=0.020). However, in the cystectomy cohort (n=88), MRE11 expression was not associated with cancer-specific survival, commensurate with MRE11 being a predictive marker. High MRE11 expression in the combined radiotherapy cohort had a significantly better cancer-specific survival compared with the high expression cystectomy cohort (69.9% vs 53.8% 3 year cause-specific survival, p=0.021). In this validated immunohistochemistry study, MRE11 protein expression was demonstrated and confirmed as a predictive factor associated with survival following bladder cancer radiotherapy, justifying its inclusion in subsequent trial design. MRE11 expression may ultimately allow patient selection for radiotherapy or cystectomy, thus improving overall cure rates.

Keywords: bladder cancer, radiotherapy, radiobiology, MRE11, predictive biomarker

Introduction

Bladder cancer is the 5th commonest cancer in the UK (1). Radical radiotherapy and surgical removal of the bladder (cystectomy) achieve similar cure rates in muscle invasive disease (2) but they have never been compared in a randomised-controlled trial. Recently in the UK, the SPARE selective bladder preservation trial feasibility study demonstrated the significant barriers to recruitment encountered when attempting such a randomisation (3). Treatment choices are thus largely governed by patient preferences and physician bias, as there are currently no means of predicting treatment response and subsequent survival (4). If predictive markers could be identified, patients might then be selected for the treatment most likely to benefit them personally, which would have the added advantage of maximising overall cure rates.

DNA double-strand breaks (DSB) are the most lethal form of ionising radiation-induced DNA damage. Failure to repair such breaks results in tumour cell death. Immediately following cellular exposure to ionizing radiation, the damage is detected by the MRE11-RAD50-NBS1 (MRN) complex, resulting in rapid recruitment of signalling and repair proteins, and alteration of chromatin structure, including histone modifications, to permit protein access to the DNA (5). MRE11/RAD50 tethers broken DNA ends and NBS1 recruits ATM (6). Upon activation, ATM phosphorylates the histone H2AX, thus promoting DSB repair and amplifying DSB signalling (7), and it phosphorylates p53, NBS1, CHK2 and other proteins, to activate cell cycle checkpoints (6). MRE11 is also involved in DNA end-resection during DSB repair. If damage is overwhelming, however, the cell may die by apoptosis or senesce (7). Therefore, we hypothesised that low tumour expression of DNA DSB signalling proteins would be associated with better outcome following radical radiotherapy in bladder cancer, due to decreased DNA repair. However, we would not expect it to be related to outcome following surgery, as the treatment efficacy of surgery is not mediated via DNA damage mechanisms. Data are sparse regarding expression of these proteins in relation to radiotherapy outcomes. Arlehag et al (8) found no association for ATM expression in colorectal cancer but, surprisingly, low expression of MRN complex proteins was associated with a worse radiotherapy response in breast cancer (9).

Approximately 50% of human cancers have TP53 mutations (10). More than 80% are in exons 5 to 8 (coding the p53 DNA binding domain); over 75% of these are missense mutations. Both TP53 mutations and p53 protein expression by immunohistochemistry (IHC) have been studied in tumours clinically but no clear association has been demonstrated between the two (11) and the literature regarding tumour p53 IHC expression and radiotherapy outcomes is conflicting (11-18). In this study we assessed protein expression by immunohistochemistry for ATM, MRE11, RAD50, NBS1 and H2AX in a cohort of bladder cancer patients treated with radical radiotherapy (RT) in a single institution from 1995-2000, and validated our results in a second cohort treated similarly from 2002-2005. We also studied TP53 mutations in exons 5-8. Having successfully validated the association between MRE11 expression and cause-specific survival following RT, we used the cystectomy cohort from 1996-2005 from the same institution to establish whether the assay was prognostic for disease outcome or predictive of response to radiotherapy.

Methods

Ethical approval was obtained from Leeds (East) Local Research Ethical Committee (studies 02/060, 02/192 and 04/Q1206/62).

Study population

We studied two cohorts of patients, Cohort A (1995-2000) and Cohort B (2002-2005), treated with radical radiotherapy for transitional cell carcinoma of the bladder at the Leeds Cancer Centre, West Yorkshire, UK, and one cohort of patients treated with radical cystectomy at the Leeds Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust (1995-2005). Cohort B patients were prospectively recruited in clinic and gave informed consent for use of their tissue. Their outcome data was prospectively collected in clinic by use of a standard proforma. Details of radiotherapy treatments and cohort A patients have been described previously (19). Whereas cohort A patients received 55 Gy in 20 fractions over 4 weeks using a CT-planned three/four field 2-dimensional cylinder technique, for Cohort B patients the technique was 3D-conformal and 11% of patients received additional treatments (Table 1). Details of the cystectomy technique have been described previously (2).

Table 1.

Demographics of test Cohort A (1995-2000) and validation Cohort B (2002-2005) cohorts. p-value from Pearson’s chi-square test unless otherwise stated.

| Variable | Test set (1995-2000) No of patients† (% ) |

Validation set (2002-2005) No of patients§ (% ) |

Cystectomy set (1995-2005) No of patients (%) |

p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Age | Median (range) |

75 yrs (42-92) |

77 yrs (55-89) |

68 yrs (43-79) |

<0.001 * |

|

| |||||

| Gender | Male Female |

65 (74.7) 22 (25.3) |

72 (77.4) 21 (22.6) |

66 (75.0) 22 (25.0) |

0.90 |

|

| |||||

| Tumour stage | T1 | 3 (3.4) | 3 (3.2) | 0 (0) | 0.34 |

| T2 | 41 (47.1) | 47 (50.5) | 46 (52.3) | ||

| T3 | 36 (41.5) | 31 (33.4) | 28 (31.8) | ||

| T4 | 6 (6.9) | 8 (8.6) | 13 (14.8) | ||

| Tx | 1 (1.1) | 4 (4.3) | 1 (1.1) | ||

|

| |||||

| Nodal class | N0 | 76 (87.4) | 85 (91.4) | 77 (87.5) | 0.24 |

| N+ | 4 (4.6) | 4 (4.3) | 9 (10.2) | ||

| Nx | 7 (8.0) | 4 (4.3) | 2 (2.3) | ||

|

| |||||

| Histological grade # | G3 | 73 (84.0) | 79 (84.9) | 80 (90.9) | 0.45 |

| <G3 | 13 (14.9) | 10 (10.8) | 8 (9.1) | ||

| Gx | 1 (1.1) | 4 (4.3) | 0 (0) | ||

|

| |||||

| Hydronephrosis | No | 69 (79.3) | 62 (66.6) | 48 (54.5) | 0.0002 |

| Yes | 13 (14.9) | 29 (31.2) | 40 (45.5) | ||

| Unknown | 5 (5.8) | 2 (2.2) | 0 (0 | ||

|

| |||||

|

Neoadjuvant/concurrent

chemotherapy |

No | 87 (100) | 83 (89.2) | 82 (93.2) | |

| Yes | 0 (0) | 10 (10.8) | 6 (6.8) | ||

|

| |||||

| Salvage Cystectomy | No | 79 (90.8) | 86 (92.5) | Not applicable | |

| Yes | 8 (9.2) | 7 (7.5) | |||

|

| |||||

| Chemotherapy ** | No | 81 (93.1) | 88 (94.6) | 84 (95.5) | |

| Yes | 6 (6.9) | 5 (5.4) | 4 (4.5) | ||

p-value from two-sided f-test.

All patients in cohort B had transitional cell carcinoma: four had some squamous elements and one had sarcomatoid differentiation.

A comparison of the median and range of semiquantitative scores for the six proteins in the group of patients who had died of bladder cancer and those still alive at 3 years is shown in Supplementary Table 4.

Three patients in the validation set received neoadjuvant chemotherapy, two received concurrent carbogen and nicotinamide as part of a phase III clinical trial and five patients received 100 mg/m2 of gemcitabine weekly x4 concurrently with radiotherapy in a phase II clinical trial.

Salvage chemotherapy for patients treated by radiotherapy and adjuvant chemotherapy for patients treated by surgery

Formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tumour samples taken at pre-treatment transurethral resection of the bladder tumour (TURBT) were available in 91 Cohort A, 93 Cohort B and 88 surgical cohort patients. For each patient, a haematoxylin and eosin (H&E) stained section was reviewed by a consultant uropathologist and areas of invasive transitional cell carcinoma were outlined.

Immunohistochemistry of DNA damage signalling proteins and Ki67

Immunohistochemistry was undertaken using a standard streptavidin-biotin complex method. In brief FFPE sections (4 mm) were deparaffinised, rehydrated and washed. Endogenous peroxidases were blocked using 3% hydrogen peroxide, followed by antigen retrieval in 10 mM citrate buffer pH 6.0 for 20 minutes. Slides were incubated with primary antibody: anti-MRE11 (1:150), anti-RAD50 (1:100), anti-NBS1 (1:2000) (ab214, ab89 and ab398 respectively, Abcam plc, Cambridge, UK), anti-Ki67 (1:400, Dako, Denmark) and anti-H2AX (1:700, Bethyl Labs, TX, USA) for 90 minutes at room temperature or anti-ATM antibody (1:50, Stratech, UK) overnight at 4°C. Sections were incubated in biotinylated secondary antibody for 30 minutes, followed by streptavidin peroxidase (Dakocytomation, Denmark) for a further 30 minutes. Bound antibodies were visualised using diaminobenzidine (Dakocytomation, Denmark) and counterstained with haematoxylin.

Anti-MRE11, NBS1, RAD50 and ATM antibodies were titrated against the same formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded breast adenocarcinoma, the positive control for all subsequent experiments, including the cystectomy cohort samples, using a range of dilutions starting with the datasheet recommendation. The final dilution was chosen by two observers so that on a scale of 1-3 the positive control scored 2. Normal urothelium was present in less than 15% of patients and could therefore not be used for internal reference purposes. Sections of normal tonsil were used for anti-H2AX and Ki67 antibodies. The antibodies were omitted from the negative controls. Digital images were captured from 6 to 10 random fields from within invasive tumour areas (× 600 magnification) using the Olympus BX50 microscope and c-3030 camera, and 100 tumour cells were counted from each field as positively or negatively stained (by LN for Cohort A, AC for Cohort B and MTWT for the cystectomy cohort). Cohort A were counted independently by a second observer (AC) with comparable results. In addition, staining intensity (0-3) (Figure 1) was scored blind independently by two observers (AC and AEK for RT patients, and MTWT and AEK for cystectomy patients), and discordant scores (approx 10%) reviewed and a consensus reached. The median percentage of positive cells was multiplied by the modal intensity to give a semi-quantitative score (SQS). Five percent of sections from Cohort A were scored by a second observer (AC) with comparable results. Cohort A was used as a training set to establish cut-off algorithms and the same cut-offs were used for the validation Cohort B, and the surgical cohort (for MRE11 only).

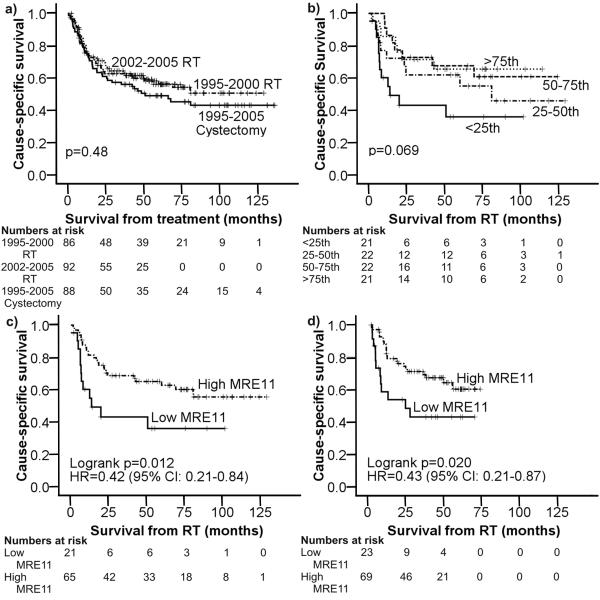

Figure 1.

Kaplan-Meier cause-specific survival curves for: a) test, validation and cystectomy cohorts, b) MRE11 expression by quartile in the test cohort A, c) test Cohort A comparing the groups above and below the 25th percentile (low indicates MRE11 expression below the 25th centile, whilst high indicates MRE11 expression above this), d) validation Cohort B comparing the groups above and below the 25th percentile.

TP53 mutation detection and gene sequencing

Ten μm sections (one to three per patient) were stained with haematoxylin and eosin and areas containing at least 70% of tumour macrodissected for DNA extraction using the QIAamp DNA micro kit (Qiagen, UK). Amplified DNA (primer sequences available on request) from TP53 exons 5-8 was screened for mutations by single strand conformation polymorphism (SSCP) analysis. Briefly, PCR was carried out using FAM or HEX labelled primers. The products were diluted and subjected to capillary electrophoresis at 18 and 30 °C using a 3100 Genetic Analyser (Applied Biosystems), in 5% GeneScan polymer (Applied Biosystems), 5% glycerol, 1x Tris-TAPS-EDTA buffer (Applied Biosystems). Data analysis was performed using GeneScan and Genotyper software (Applied Biosystems) and by visual inspection of electropherograms. Samples with possible mutations were sequenced using standard protocols and analysed using ABI sequence analysis software by two independent observers.

Statistical analysis

Population demographics were compared among the three cohorts using Pearson Chi-squared tests and two-sided f-tests. The outcome measure was survival time. In each cohort, Kaplan Meier curves were plotted for cause-specific survival (CSS; deaths due to bladder cancer only with other deaths censored) and the log-rank statistic used to compare survival times across categories of MRE11 protein expression levels. Summary statistics of protein expression were calculated for the protein expression semi-quantitative scores and pair-wise Spearman’s rank correlations between markers. Cohort A scores were grouped into approximate quartiles. Hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals were estimated from Cox Proportional Hazard models adjusted for other model covariates, i.e. age, hydronephrosis, grade, stage, high/low MRE11 expression and TP53 mutation in the univariate model, and for the multivariate model all these covariates except TP53 mutation (lowest quarter as the reference). Potentially interesting markers were then assessed in the same way for cohort B and subsequently MRE11 was assessed in the cystectomy cohort. Assuming high protein expression in 75% of samples and low expression in 25% of samples, with a 5% significance level, in a cohort of 88 patients, 60 cause specific survival (CSS) events would give an 87% power to detect a HR of 0.4, and 44 CSS events would give a 75% power to detect a HR of 0.4.

Results

Expression of DSB signalling proteins

In cohorts A and B and the cystectomy cohort, 87, 93 and 88 patient samples respectively had sufficient invasive tumour cells for analysis. Between cohorts A and B, the study populations’ demographics were similar (Table 1) despite the intervening seven years, although the proportion with hydronephrosis (14.9% v 31.2%, Chi2(1)=6.02, p=0.018) was higher in Cohort B. When all three cohorts were compared, the cystectomy cohort was significantly younger than cohorts A and B (median age 68 v 75 v 77 years respectively, p<0.001) and a higher proportion had hydronephrosis (45.5% v 14.9% v 31.2%, Chi2(2)=17.27, p<0.001). This would be in keeping with the local practice of treating younger (hence fitter) patients and patients with hydronephrosis with surgery. There was no significant difference in 3-year cause-specific survival (CSS) among the three cohorts (61.8%, 65.1% and 56.0%, Chi2(2)=1.52, p=0.48) (Figure 1a). The overall 3 year CSS of all 3 cohorts combined was 62.1%.

A range of nuclear expression was seen for all DNA damage signalling proteins in terms of the number of positive cells and staining intensity (relative to the positive controls, Table 2 and Supplementary Figure 1). In cohort A, dividing groups at the 25th, 50th and 75th centiles, there was no significant association between MRE11, NBS1, RAD50, ATM, H2AX or Ki67 protein expression and CSS (Figure 1b (MRE11) and Table 2). However, inspection of the curves for cohort A showed visual differences between patients with values of MRE11 expression less than the 25th centile compared with over. Improved 3 year CSS was demonstrable in cohort A for patients whose tumours had high MRE11 expression (Figure 1c, 68.7% if >25th vs 43.1% if <25th centile, SQS cutpoint 130 at 25th centile, HR=0.42, 95%CI 0.21-0.84, p=0.012). This was confirmed in Cohort B with 3-year CSS of 71.2% if >25th and 43.0% if <25th centile respectively SQS cutpoint 76 at 25th centile, (Figure 1d, HR=0.43, 95%CI 0.21-0.87, p=0.020), and combined A+B cohorts’ 3-year CSS were 69.9% and 43% respectively (Figure 2a, HR=0.43, 95%CI 0.26-0.71, p<0.001). When normal urothelium was present, normal/tumour differences in MRE11 expression levels were found in 8/9 (89%) of cases, with lower tumour expression in seven cases and higher in one. By semi-quantitative score, tumour MRE11 expression was significantly correlated with NBS1 expression (r=0.22, p=0.003), RAD50 and ATM were significantly correlated (r=0.20, p=0.008), and ATM and NBS1 were negatively correlated with Ki67 expression (r=−0.19, p=0.010 and r=−0.23, p=0.002 respectively). None of the other proteins correlated with Ki67 expression. There was no association between protein expression and stage or grade of tumour (data not shown).

Table 2.

Test cohort A (1995-2000): DNA damage signalling proteins’ median percentage score, intensity and semi-quantitative score (SQS) with ranges; median expression scores with ranges in patients who died of bladder cancer or were still alive at 3 years (Ki67 was scored as a percentage of positive nuclei alone); associations of protein expression by quartile with CSS.

| Protein | Percentage positive nuclei: Median (range) |

Intensity: Mode (range) |

Semiquantitative score: Median (range) |

Died of bladder cancer at 3 years: Number Median score (range) |

Alive at 3 years: Number Median score (range) |

Quartile | No of cases | 3yr cause-specific survival |

p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MRE11 | 91.2 (17.1-98.6) |

2 (0-3) |

182 (28-296) |

31 167 (48-294) |

45 186 (28-296) |

≤ 25th | 21 | 43.1 | p=0.069 |

| 25-50th | 23 | 65.5 | |||||||

| 50-75th | 21 | 71.4 | |||||||

| ≥ 75th | 21 | 71.4 | |||||||

| NBS1 | 62.6 (6.0-93.2) |

2 (0-3) |

125 (6-280) |

30 122 (6-239) |

45 110 (11-280) |

≤ 25th | 21 | 57.1 | p=0.76 |

| 25-50th | 22 | 68.2 | |||||||

| 50-75th | 22 | 67.2 | |||||||

| ≤ 75th | 21 | 61.8 | |||||||

| RAD50 | 95.3 (24.3-99.9) |

2 (0-3) |

193 (24-299) |

31 192 (84-297) |

45 191 (24-299) |

≤ 25th | 21 | 66.3 | p=0.94 |

| 25-50th | 23 | 60.9 | |||||||

| 50-75th | 22 | 61.9 | |||||||

| ≥ 75th | 21 | 62.0 | |||||||

| ATM | 85.2 (24.0-97.3) |

2 (0-3) |

174 (6-292) |

30 172 (48-285) |

45 170 (48-292) |

≤ 25th | 22 | 72.7 | p=0.83 |

| 25-50th | 22 | 54.5 | |||||||

| 50-75th | 21 | 70.8 | |||||||

| ≥ 75th | 21 | 56.7 | |||||||

| H2AX | 7.4 (1-60.0) |

1 (0-3) |

10 (1-149) |

29 16 (1-120) |

45 8 (1-149) |

≤ 25th | 20 | 79.2 | p=0.49 |

| 25-50th | 21 | 65.5 | |||||||

| 50-75th | 23 | 63.6 | |||||||

| ≥ 75th | 21 | 50.8 | |||||||

| Ki67 | 27.8 (2.0-74.0) |

30 30 (2-74) |

45 26 (5-52) |

≤ 25th | 21 | 63.3 | p=0.56 | ||

| 25-50th | 23 | 60.1 | |||||||

| 50-75th | 21 | 74.8 | |||||||

| ≥ 75th | 21 | 51.9 |

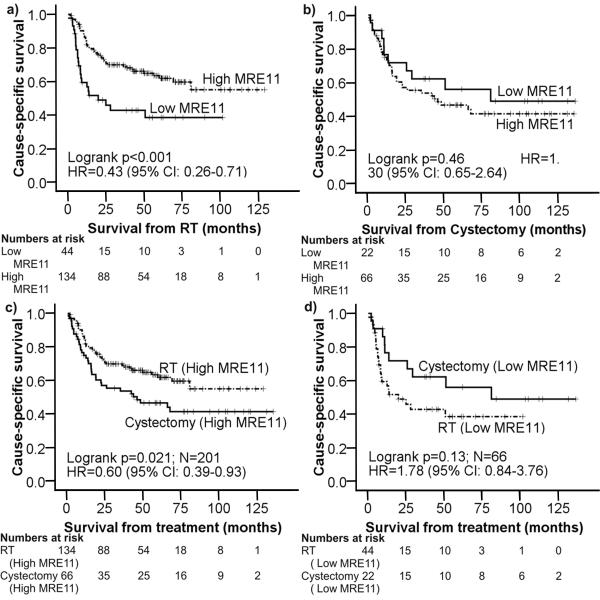

Figure 2.

MRE11 as a prognostic/predictive marker. Kaplan-Meier cause-specific survival curves for: a) combined Cohort A and Cohort B comparing the groups above and below the 25th percentile; b) 1995-2005 cystectomy cohort comparing the groups above and below the 25th percentile; c) MRE11 as a predictive factor: high MRE11 (>25%) in RT vs cystectomy patients; d) MRE11 as a predictive factor: low MRE11 (=<25%) in RT vs cystectomy patients.

In the cystectomy cohort, MRE11 expression did not significantly influence 3 year CSS (Figure 2b, 53.8% for >25th centile vs 62.2% for <25th centile, SQS cutpoint 58 at 25th centile, HR=1.30, 95%CI 0.65-2.64, p=0.46). MRE11 expression did not influence 3 year CSS when the cystectomy cohort was combined with Cohort A or Cohort B, in order to have a balanced number of radiotherapy and cystectomy patients (n=88+86 and n=88+93 respectively, Supplementary Figure 2). For individuals with high MRE11 expressing tumours, RT patients (Cohort A + Cohort B) had better 3 year CSS compared to cystectomy patients (Figure 2c, 69.9% vs 53.8%, HR=0.60, 95%CI 0.39-0.93, p=0.021). In individuals with low MRE11 expressing tumours, there was a non-significant poorer outcome in RT cases compared to cystectomy cases but case numbers were small (44 RT, 22 cystectomy; Figure 2d, 42.8% vs 62.2, HR1.78, 95%CI 0.84-3.76, p=0.13). These results would be supportive of MRE11 being a predictive marker for radiotherapy response rather than prognostic in bladder cancer.

TP53 mutation and radiotherapy outcome

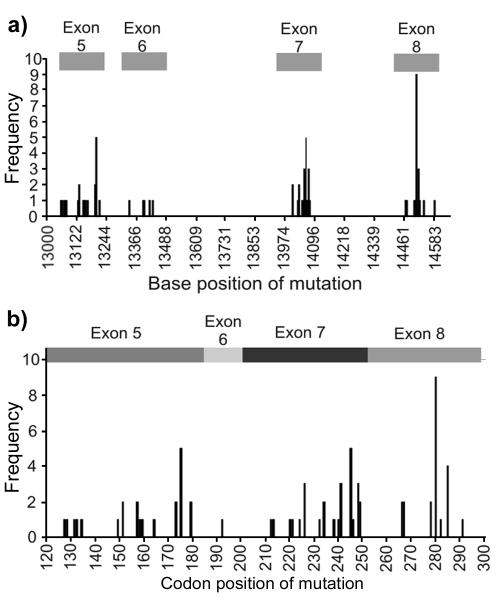

Of the 160 bladder tumour samples tested for TP53 mutations, 66 had at least one TP53 mutation. Eighty-three mutations were found in total, nine samples having more than one mutation. Six were silent, three frameshift, one splice site, one intronic and 72 missense. Dysfunctional mutations were defined as those with evidence of an in vitro functional effect (20).There were mutation clusters around bases 13203, 14060 and 14508 (Figure 3a), with codons 175, 245 and 280, in exons 5, 7 and 8 respectively, most commonly mutated (Figure 3b). There was no significant difference in CSS between those patients having tumours with a predicted dysfunctional TP53 mutation and the remainder (data not shown).

Figure 3.

a) Frequency and position of base mutations in TP53; b) Frequency of mutations by codon position in exons 5-8 of p53.

Multivariate analysis of predictors for cause-specific survival

Using a multivariate Cox proportional hazards analysis (Table 3), hydronephrosis was a significant prognostic factor in cohort A (p=0.001), cohorts A and B combined (p=0.003) and the cystectomy cohort (p<0.001). In Cohort A, MRE11 protein expression was a borderline significant independent predictor for CSS after treatment with radiotherapy (p=0.076). However, this was confirmed as an independent predictor of CSS in Cohort B (p=0.010), with combined analysis of the two cohorts increasing the statistical significance of the MRE11 result (p<0.001). In contrast, MRE11 was not found to be a significant independent predictor of CSS in the cystectomy cohort (p=0.29).

Table 3.

Multivariate cause-specific analyses using Cox proportional hazards regression analysis to determine hazard ratios (HR) and p-values in the 1995-2000 and 2002-2005 radiotherapy datasets (Cohorts A and B) and the 1995-2005 cystectomy dataset. Numbers in bold represent significance at the 5% level.

| Cohort A | Cohort B | Combined A + B | Cystectomy | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Category (87 cohort A, 93 cohort B, 88 cystectomy) |

Univariate model HR (95% CI) (p-value) |

Multivariate model HR (95% CI) (p-value |

Univariate model HR (95% CI) (p-value) |

Multivariate model HR (95% CI) (p-value) |

Univariate model HR (95% CI) (p-value |

Multivariate model HR (95% CI) (p-value) |

Univariate model HR (95% CI) (p-value) |

Multivariate model HR (95% CI) (p-value) |

| Age (years) | 1.00 (0.96- 1.03) |

0.98 (0.95- 1.02) |

1.02 (0.98- 1.07) |

1.03 (0.98- 1.08) |

1.01 (0.98- 1.04) |

1.00 (0.98- 1.03) |

1.03 (0.99- 1.08) |

1.03 (0.99- 1.07) |

| (p=0.96) | (p=0.38) | (p=0.36) | (p=0.27) | (p=0.63) | (p=0.77) | (p=0.12) | (p=0.77) | |

| Hydronephrosis | ||||||||

| No (69, 62, 48) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Yes (13, 29, 40) |

3.72 (1.75-

7.87) (p<0.001) |

4.21 (1.74-

10.15) (p=0.0014) |

1.84(0.91- 3.69) (p=0.09) |

1.71 (0.78- 3.78) (p=0.18) |

2.37 (1.43-

3.94) (p<0.001) |

2.29 (1.33-

3.94) (p=0.003) |

3.20 (1.73-

5.90) (p<0.001) |

3.37 (1.79-

6.36) (p<0.001) |

| Grade | ||||||||

| <G3 (13, 10, 8) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| G3 (73, 79, 80) | 1.00 (0.41- 2.41) (p=1.00) |

1.26 (0.51- 3.11) (p=0.62) |

1.20 (0.37- 3.94) (p=0.76) |

1.15 (0.35- 3.85) (p=0.82) |

1.05 (0.52- 2.13) (p=0.88) |

1.10 (0.55- 2.24) (p=0.78) |

2.79 (0.68- 11.50) (p=0.16) |

2.68 (0.63- 11.40) (p=0.18) |

| Tumour -stage | ||||||||

| 1+2 (44, 50, 46) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| 3+4 (42, 39, 41) | 1.32 (0.68- 2.58) (p=0.42) |

1.26 (0.62- 2.52) (p=0.52) |

2.08 (1.05-

4.12) (p=0.037) |

1.96 (0.94- 4.08) (p=0.073) |

1.66 (1.03-

2.68) (p=0.038) |

1.60 (0.96- 2.65) (p=0.069) |

1.96 (1.07-

3.56) (p=0.028) |

1.63 (0.89- 3.00) (p=0.11) |

| MRE11 | ||||||||

| Low (21, 23, 22) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| High (65, 70, 66) |

0.46 (0.22-

0.97) (p=0.042) |

0.50 (0.23- 1.08) (p=0.076) |

0.46 (0.22-

0.96) (p=0.037) |

0.36 (0.17-

0.78) (p=0.010) |

0.47 (0.28-

0.78) (p=0.004) |

0.39 (0.23-

0.66) (p<0.001) |

1.45 (0.70- 3.02) (p=0.32) |

1.50 (0.70- 3.20) (p=0.29) |

|

Functional TP53

mutation |

||||||||

| 0 (57, 55) | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| 1 (30, 18) | 1.36 (0.70- 2.63) (p=0.37) |

0.66 (0.27- 1.63) (p=0.37) |

1.04 (0.62- 1.74) (p=0.89) |

|||||

Discussion

To our knowledge this is the first study to have investigated the DSB signalling proteins ATM, MRE11, RAD50, NBS1 and H2AX in bladder cancer radiotherapy patients. We expected that patients with low expression of these proteins would have improved outcomes following radiotherapy due to reduced DNA DSB repair. Whilst we found no correlation for ATM, RAD50, NBS1 and H2AX, we found the opposite effect for MRE11. In two independent test and validation cohorts, the second prospectively acquired, with similar 3-year cause specific survival rates (61.8% and 65.1% respectively), comparable to those of other centres (13, 15, 17, 21-24), our data show that low tumour MRE11 protein expression level is an independent factor associated with worse cause-specific survival following radical radiotherapy for bladder cancer. Although not validated, similar results have been reported in breast cancer (9) with high expression of MRN complex proteins associated with improved prognosis and better outcome following adjuvant radiotherapy. Additionally, Rhee et al (25) demonstrated that over-expression of NBS1 using an adenoviral vector resulted in radiosensitization in a head and neck squamous cell carcinoma cell line. As MRE11 expression could be a general prognostic marker in bladder cancer rather than predictive of radiotherapy treatment response per se, we also studied a cohort of cystectomy patients treated at the same institution within the same era and found that for these patients MRE11 expression was not associated with cause-specific survival, making its role as a prognostic marker unlikely. However, the role of MRE11 expression as a predictive marker was strengthened when we compared cystectomy and radiotherapy cohorts; in high MRE11 expressing tumours, outcomes were better after RT than cystectomy, with a 16% absolute improvement in 3-year cause-specific survival. Results for patients with tumours of low MRE11 expression were not significant due to small numbers, but in this group patients who had cystectomy appeared to do better than those who had radiotherapy. As is routinely the case for HER2 testing in patients with breast cancer (26), MRE11 expression assessed by immuno-histochemistry in diagnostic specimens may guide patients’ choice to either have a cystectomy or radiotherapy.

We used the 25th centile of each cohort as a cut-point, because stratification by quartiles was more appropriate in the absence of a linear relationship between MRE11 and cause specific survival (using the SAS version 9.1 PHREG procedure). The significance of the 25th centile cutpoint was maintained despite a difference in its numerical value (130 vs 76). However, use of the 130 cutpoint in cohort B still gave a significant result (p=0.006, data not shown). Variations in measures of marker expression may be due to differences in pre-analytical (eg. length and type of fixation), analytical (eg. test reagents, methodology) and post analytical (eg. interpretation, calibration of automation) factors (26-28). All these factors must be standardized within each laboratory for the test to be useful clinically, and test material, with known levels of marker expression, must be incorporated into each assay run, as for HER2 testing (26). A similar approach will be required for MRE11 expression in muscle invasive bladder cancer using samples from phase III clinical studies with known outcome data to establish a standardized protocol for test performance and interpretation, followed by a prospective clinical trial, where patients’ treatments are selected on the basis of marker expression (29). We believe that we are the first to report the association of MRE11 expression and radiotherapy outcome in bladder cancer, but interestingly Soderlund et al (9) found a similar result in breast cancer, although in that study the result was not validated. This implies that this finding might have larger relevance to the cancer community, so this marker should also be tested in other important common tumour sites such as prostate, colorectal and lung cancer.

Our limited data suggests that the low expression of MRE11 that we observed in tumours is in fact reduced expression relative to that seen in normal urothelium. Reduced MRE11 protein expression due to MRE11 mutations, epigenetic silencing by promoter hypermethylation, loss of heterozygosity at 11q21, alterations in transcription or translation, or post-translational modifications could result in MRN complex instability. Although we initially hypothesised that patients would have a better outcome due to reduced DNA repair, surprisingly we found the opposite result. Failure of induction of the DNA damage signalling cascade following DNA damage could in fact lead to radioresistance as, through less efficient activation of the downstream apoptotic cell death pathway and/or due to lack of checkpoint arrest, the cells would continue to proliferate. Giannini et al (30) found cells containing an MRE11 frameshift mutation to have an impaired S-phase checkpoint and Zhang et al (31) found that siRNA-mediated knockdown of NBS1 expression in B-lymphoblasts resulted in impaired checkpoint activation, reduced apoptosis and radioresistance. In our study the presence in tumour of a dysfunctional tumour TP53 mutation had no significant impact on patient survival following radiotherapy. We observed the mutations coding for codons 175, 245, 248 and 280 (32, 33), which are relatively common in bladder cancer. Although MRE11 and p53 are both involved in cell cycle control, we found no association between MRE11 protein expression and TP53 mutation.

The literature concerning the role of p53 in radiosensitivity is conflicting: in vitro, TP53 mutations are found to be associated with either radiosensitivity (23) or radioresistance (34) and in clinical series TP53 mutations are associated with both improved and worse outcomes following ionising radiation (35-37). Also, no clear association has been demonstrated between TP53 mutations and p53 protein expression by immunohistochemistry (IHC) (11). In a large systematic review of p53 expression and TP53 mutations and outcomes in colo-rectal cancer, Munro et al (36) concluded that the heterogenous results and publication bias meant that no clear consensus could be established.

However, we have validated, in two independent cohorts, MRE11 expression by IHC as a potential predictive marker for outcome following radical radiotherapy for muscle invasive bladder cancer. In our cystectomy series from the same era, MRE11 was not associated with outcome, implying that MRE11 expression is not a prognostic factor in bladder cancer. Ultimately, if these results are validated in clinical trials, patients may be selected for either RT or surgery on the basis of MRE11 expression by IHC in their pre-treatment TURBT specimen, thus increasing overall cure rates in this disease.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank the Northern and Yorkshire Cancer Registry and Information Service (NYCRIS) for providing us with some cause of death data, Filomena Esteves for advice on immunohistochemical staining, Madeleine McCarthy and Sanjeev Kotwal for help with data retrieval from patients’ notes and Andy Sharpe for DNA extractions. Thanks to Professor Penny Jeggo, Dr Janet Hall and Dr Anderson Ryan for helpful discussions.

Financial support: This work was funded by Yorkshire Cancer Research (L319) and Cancer Research UK (C19217/A6082, C15140/A11505)

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: None other than AEK who, as an invited speaker, had part of her registration and accommodation reimbursed at the BAUS Section of Oncology Annual Meeting, November 2009.

References

- 1.Cancer incidence –UK statistics [Internet] Cancer Research UK; London: [cited 2010 Mar 24]. updated 2009 Aug 27. Available from: http://info.cancerresearchuk.org/cancerstats/incidence/ [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kotwal S, Choudhury A, Johnston C, Paul AB, Whelan P, Kiltie AE. Similar treatment outcomes for radical cystectomy and radical radiotherapy in invasive bladder cancer treated at a United Kingdom specialist treatment center. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2008;70:456–63. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2007.06.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moynihan C, Hall E, Lewis R, Birtle A, Mead GM, Huddart R. SPARE:A qualitative study investigating randomization barriers in a Selective Bladder Preservation trial (SBP) J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:15s. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Colquhoun AJ, Jones GD, Moneef MA, Bowman KJ, Kockelbergh RC, Symonds RP, et al. Improving and predicting radiosensitivity in muscle invasive bladder cancer. J Urol. 2003;169:1983–92. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000067941.12011.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Iijima K, Ohara M, Seki R, Tauchi H. Dancing on damaged chromatin: functions of ATM and the RAD50/MRE11/NBS1 complex in cellular responses to DNA damage. J Radiat Res (Tokyo) 2008;49:451–64. doi: 10.1269/jrr.08065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lavin MF. ATM and the Mre11 complex combine to recognize and signal DNA double-strand breaks. Oncogene. 2007;26:7749–58. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jackson SP, Bartek J. The DNA-damage response in human biology and disease. Nature. 2009;461:1071–8. doi: 10.1038/nature08467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Arlehag L, Adell G, Knutsen A, Thorstenson S, Sun XF. ATM expression in rectal cancers with or without preoperative radiotherapy. Oncol Rep. 2005;14:313–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Soderlund K, Stal O, Skoog L, Rutqvist LE, Nordenskjold B, Askmalm MS. Intact Mre11/Rad50/Nbs1 complex predicts good response to radiotherapy in early breast cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2007;68:50–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2006.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hollstein M, Shomer B, Greenblatt M, Soussi T, Hovig E, Montesano R, et al. Somatic point mutations in the p53 gene of human tumors and cell lines: updated compilation. Nucleic Acids Res. 1996;24:141–6. doi: 10.1093/nar/24.1.141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hall PA, McCluggage WG. Assessing p53 in clinical contexts: unlearned lessons and new perspectives. J Pathol. 2006;208:1–6. doi: 10.1002/path.1913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Garcia del Muro X, Condom E, Vigues F, Castellsague X, Figueras A, Munoz J, et al. p53 and p21 Expression levels predict organ preservation and survival in invasive bladder carcinoma treated with a combined-modality approach. Cancer. 2004;100:1859–67. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jahnson S, Risberg B, Karlsson MG, Westman G, Bergstrom R, Pedersen J. p53 and Rb immunostaining in locally advanced bladder cancer: relation to prognostic variables and predictive value for the local response to radical radiotherapy. Eur Urol. 1995;28:135–42. doi: 10.1159/000475038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moonen L, Ong F, Gallee M, Verheij M, Horenblas S, Hart AA, et al. Apoptosis, proliferation and p53, cyclin D1, and retinoblastoma gene expression in relation to radiation response in transitional cell carcinoma of the bladder. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2001;49:1305–10. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(00)01503-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Osen I, Fossa SD, Majak B, Rotterud R, Berner A. Prognostic factors in muscle-invasive bladder cancer treated with radiotherapy: an immunohistochemical study. Br J Urol. 1998;81:862–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.1998.00657.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Qureshi KN, Griffiths TR, Robinson MC, Marsh C, Roberts JT, Lunec J, et al. Combined p21WAF1/CIP1 and p53 overexpression predict improved survival in muscle-invasive bladder cancer treated by radical radiotherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2001;51:1234–40. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(01)01801-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rotterud R, Berner A, Holm R, Skovlund E, Fossa SD. p53, p21 and mdm2 expression vs the response to radiotherapy in transitional cell carcinoma of the bladder. BJU Int. 2001;88:202–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.2001.02268.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wu CS, Pollack A, Czerniak B, Chyle V, Zagars GK, Dinney CP, et al. Prognostic value of p53 in muscle-invasive bladder cancer treated with preoperative radiotherapy. Urology. 1996;47:305–10. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(99)80443-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sak SC, Harnden P, Johnston CF, Paul AB, Kiltie AE. APE1 and XRCC1 protein expression levels predict cancer-specific survival following radical radiotherapy in bladder cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:6205–11. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-0045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Petitjean A, Mathe E, Kato S, Ishioka C, Tavtigian SV, Hainaut P, et al. Impact of mutant p53 functional properties on TP53 mutation patterns and tumor phenotype: lessons from recent developments in the IARC TP53 database. Hum Mutat. 2007;28:622–9. doi: 10.1002/humu.20495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Borgaonkar S, Jain A, Bollina P, McLaren DB, Tulloch D, Kerr GR, et al. Radical radiotherapy and salvage cystectomy as the primary management of transitional cell carcinoma of the bladder. Results following the introduction of a CT planning technique. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol) 2002;14:141–7. doi: 10.1053/clon.2002.0055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chung PW, Bristow RG, Milosevic MF, Yi QL, Jewett MA, Warde PR, et al. Long-term outcome of radiation-based conservation therapy for invasive bladder cancer. Urol Oncol. 2007;25:303–9. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2006.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ribeiro JC, Barnetson AR, Fisher RJ, Mameghan H, Russell PJ. Relationship between radiation response and p53 status in human bladder cancer cells. Int J Radiat Biol. 1997;72:11–20. doi: 10.1080/095530097143491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rodel C, Grabenbauer GG, Rodel F, Birkenhake S, Kuhn R, Martus P, et al. Apoptosis, p53, bcl-2, and Ki-67 in invasive bladder carcinoma: possible predictors for response to radiochemotherapy and successful bladder preservation. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2000;46:1213–21. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(99)00544-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rhee JG, Li D, Suntharalingam M, Guo C, O’Malley BW, Jr., Carney JP. Radiosensitization of head/neck squamous cell carcinoma by adenovirus-mediated expression of the Nbs1 protein. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2007;67:273–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2006.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wolff AC, Hammond ME, Schwartz JN, Hagerty KL, Allred DC, Cote RJ, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology/College of American Pathologists guideline recommendations for human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 testing in breast cancer. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2007;131:18–43. doi: 10.5858/2007-131-18-ASOCCO. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bussolati G, Leonardo E. Technical pitfalls potentially affecting diagnoses in immunohistochemistry. J Clin Pathol. 2008;61:1184–92. doi: 10.1136/jcp.2007.047720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gown AM. Current issues in ER and HER2 testing by IHC in breast cancer. Mod Pathol. 2008;21(Suppl 2):S8–S15. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2008.34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cordon-Cardo C. p53 and RB: simple interesting correlates or tumor markers of critical predictive nature? J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:975–7. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.12.994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Giannini G, Ristori E, Cerignoli F, Rinaldi C, Zani M, Viel A, et al. Human MRE11 is inactivated in mismatch repair-deficient cancers. EMBO Rep. 2002;3:248–54. doi: 10.1093/embo-reports/kvf044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhang Y, Lim CU, Williams ES, Zhou J, Zhang Q, Fox MH, et al. NBS1 knockdown by small interfering RNA increases ionizing radiation mutagenesis and telomere association in human cells. Cancer Res. 2005;65:5544–53. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-4368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Oren M. Decision making by p53: life, death and cancer. Cell Death Differ. 2003;10:431–42. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Xu X, Stower MJ, Reid IN, Garner RC, Burns PA. A hot spot for p53 mutation in transitional cell carcinoma of the bladder: clues to the etiology of bladder cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 1997;6:611–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hinata N, Shirakawa T, Zhang Z, Matsumoto A, Fujisawa M, Okada H, et al. Radiation induces p53-dependent cell apoptosis in bladder cancer cells with wild-type- p53 but not in p53-mutated bladder cancer cells. Urol Res. 2003;31:387–96. doi: 10.1007/s00240-003-0355-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Eriksen JG, Alsner J, Steiniche T, Overgaard J. The possible role of TP53 mutation status in the treatment of squamous cell carcinomas of the head and neck (HNSCC) with radiotherapy with different overall treatment times. Radiother Oncol. 2005;76:135–42. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2005.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Munro AJ, Lain S, Lane DP. P53 abnormalities and outcomes in colorectal cancer: a systematic review. Br J Cancer. 2005;92:434–44. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Saffari B, Bernstein L, Hong DC, Sullivan-Halley J, Runnebaum IB, Grill HJ, et al. Association of p53 mutations and a codon 72 single nucleotide polymorphism with lower overall survival and responsiveness to adjuvant radiotherapy in endometrioid endometrial carcinomas. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2005;15:952–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1438.2005.00159.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.