Abstract

In vertebrates and some invertebrates, odorant molecules bind to G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) on olfactory receptor neurons (ORNs) to initiate signal transduction. Phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K) activity has been implicated physiologically in olfactory signal transduction, suggesting a potential role for a GPCR-activated class I PI3K. Using isoform-specific antibodies, we identified a protein in the olfactory signal transduction compartment of lobster ORNs that is antigenically similar to mammalian PI3Kγ and cloned a gene for a PI3K with amino acid homology with PI3Kβ. The lobster olfactory PI3K co-immunoprecipitates with the G protein α and β subunits, and an odorant-evoked increase in phosphatidylinositol (3,4,5)-trisphosphate can be detected in the signal transduction compartment of the ORNs. PI3Kγ and β isoform-specific inhibitors reduce the odorant-evoked output of lobster ORNs in vivo. Collectively, these findings provide evidence that PI3K is indeed activated by odorant receptors in lobster ORNs and further support the potential involvement of G protein activated PI3K signaling in olfactory transduction.

Keywords: phosphoinositide 3-kinase; olfactory signal transduction; olfactory receptor neuron; lobster; phosphatidylinositol (3,4,5)-trisphosphate

Introduction

Recent studies have revealed an emerging complexity in olfactory signal transduction. Olfactory signal transduction is best understood in the main olfactory epithelium (OE) of vertebrates, where odorant molecules bind to olfactory G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) on the apical cilia of the olfactory receptor neurons (ORNs) and initiate an adenylyl cyclase signaling cascade targeting an olfactory cyclic nucleotide gated (CNG) cation channel (Kaupp and Seifert 2002). In contrast, odorant detection in insects appears to be mediated by ligand-gated ion channels (Sato et al. 2008; Wicher et al. 2008) and variant ionotropic glutamate receptors (Benton et al. 2009), yet also may require G protein-mediated generation of cyclic nucleotide (Wicher et al. 2008) and/or phospholipid (Kain et al. 2008) second messengers.

One aspect of the complexity in olfactory signal transduction that needs to be investigated more completely is the role of phosphoinositide (PI) signaling (Wong et al., 2000; Schandar et al., 1999; Restrepo and Schild, 1999; Gold 1999; Noe and Breer 1998). There is evidence for the involvement of both canonical phospholipase C (PLC) (Boekhoff et al. 1990; Breer et al. 1990) and phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K)-mediated signaling in olfactory transduction (Zhainazarov et al., 2004; Zhainazarov and Ache 1999; Zhainazarov et al. 2001; Spehr et al. 2002). Additionally, transient receptor potential (TRP) channels, known downstream targets of PI signaling (Nilius et al., 2008), have been identified in the OE and vomeronasal organ (VNO) of mammals, as well as in insect olfactory tissue. A subset of mature ORNs express TRPM5 together with the olfactory CNG channel (Lin et al. 2007), some VNO sensory epithelium receptor cells express TRPC2 (Liman et al. 1999), and the TRPγ gene is expressed in insect olfactory cells (Chouquet et al. 2009). Collectively, these findings indicate that a better understanding of the complexity and diversity in olfactory signal transduction requires a closer examination of the potential involvement of PI signaling.

Some of the first evidence for the potential involvement of PI signaling in olfactory transduction came from lobster ORNs. Activation of lobster ORNs is GTP-dependent and can be blocked by antisera specific for Gαq (Fadool et al. 1995), suggesting that signal transduction in lobster ORNs involves G protein activation. Receptor activation stimulates PLC (Xu and McClintock 1999) and the resulting IP3 presumably targets an IP3 receptor (Munger et al. 2000) to increase intracellular calcium (Fadool and Ache 1992), arguing for a potential role for canonical PI signaling. However, PLC does not appear to be the only PI-based signaling pathway in these cells. PI3K antagonists reduce the odorant-evoked receptor potential and addition of either exogenous phosphatidylinositol (4,5)-bisphosphate (PIP2) or phosphatidylinositol (3,4,5)-trisphosphate (PIP3) modulates the suspected output channel of the cells (Zhainazarov and Ache 1999; Zhainazarov et al. 2001). This evidence for the involvement of both the PLC and the PI3K pathway makes lobster ORNs a useful animal model in which to study the integrated role of PI signaling in olfactory transduction.

If PI3K-mediated signaling is involved in olfactory transduction, it should be possible to show that the appropriate enzyme is present in the transduction compartment and can be activated by odorants sufficiently fast to account for activation of the ORNs. Here, building upon previous evidence of PI3K signaling in lobster ORNs, we show that a PI3K is expressed by lobster ORNs, that PI3K signaling is likely activated by G proteins, and that it localizes to the transduction compartment (outer dendrites). We confirm that odorants can rapidly and transiently activate PI3K in vitro. Finally, we demonstrate that activation of the enzyme is sufficiently fast in vivo to account for odorant activation by showing that blocking PI3K eliminates the fast transient response of the cells in situ. Collectively, our findings implicate the involvement of a homolog of mammalian PI3K coupled via G protein activation in lobster olfactory transduction.

Materials and methods

cDNA library preparation and gene cloning

A spiny lobster (Panulirus argus) olfactory organ cDNA library was prepared, and full length cDNA were obtained according to manufacturer’s protocol of the GeneRacer™ Kit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). Multiple clones were sequenced for each gene. All primer sequences are listed in Supplementary Table 1.

RNA extraction and reverse transcription-PCR

DNase I (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA)–treated RNA was prepared from individual clusters of ORNs with an RNAqueous-micro kit (Ambion, Austin, TX, USA). Random hexamer-primed reverse transcription (RT) was performed using Superscript III Reverse Transcriptase (Invitrogen) on the entire RNA preparation according to the manufacturer's directions. Two µl of cDNA was used as template for PCR with primers designed to amplify regions including predicted introns based on sequence comparison with PI3K genes from other species to allow detection of genomic DNA contamination. Un-transcribed RNA was used as a negative PCR control. PCR products were sequenced to confirm their identity.

Antibodies

The anti-PI3Kγ antibody (MAB2999) was purchased from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN, USA). The anti-PI3K (pan; I-19), anti-Gαq/11 (T-20) and Gβ (C-19) antibodies were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. (Santa Cruz, CA, USA). All secondary antibodies were purchased from Kirkegaard & Perry Laboratories, Inc. (Gaithersburg, MD, USA).

Protein preparation and co-immunoprecipitation

Outer dendrites were obtained by excising the tips of the sensilla from fresh olfactory organs. Each sensillum contains the ca 0.1 µm diameter branches of the outer dendrites of approximately 350 ORNs in the distal 85–90% of its length. By removing the distal 50%, pure outer dendritic membrane preparations were obtained. Protein concentrations were determined with a Coomassie Plus (Bradford) Protein Assay (Pierce, Rockford, IL, USA). For immunoprecipitation (IP), the appropriate antibodies were added at experimentally determined concentrations to the 200 µg protein samples in IP buffer (50 mM HEPES, pH 7.3 [United States Biochemical, Cleveland, OH, USA], 10 mM lauryl maltoside [United States Biochemical], 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride [Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA]) and incubated for 20 minutes at room temperature. After centrifugation, 10 µl of a 50% suspension of Protein G beads (Pierce, Rockford, IL, USA) was added to the supernatants and the samples were shaken for 1 hour. The antigen/ antibody/ protein G-agarose complexes were collected by brief centrifugation and washed with IP buffer.

Western blotting

Proteins were run on polyacrylamide gels and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. The membranes were blocked for 1 hour in 5% milk in phosphate buffered saline with 0.05% Tween 20 (PBS-T) and then incubated overnight with primary antibody diluted to the manufacturer’s suggested concentration in 1% milk in PBS-T at 4°C. The membranes were washed 6 × 10 minutes with PBS-T, followed by incubation with the appropriate horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody diluted in 1% milk in PBS-T for 2 hours. The membranes were washed again, incubated with ECL detection reagent (Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA) and the signal captured with a Fluor-S Multi-Imager (BioRad, Hercules, CA, USA).

Immunocytochemistry

Immunocytochemistry was performed following a method modified from Gisselmann et al. (2003). Briefly, lobster olfactory organs were cut into segments eight annuli in length, fixed overnight in 4% paraformaldehyde, the cuticle was softened in 0.5 M EDTA for 2 days, and then the tissue was soaked in 30% sucrose. The tissue was embedded in 4% gelatin overlaid with 4% paraformaldehyde in 0.1 M Sörenson phosphate buffer and allowed to stand at 4°C overnight. The gelatin blocks were embedded in OCT compound and frozen at −80°C. Four µm cryostat sections were made through the distal 50% of the aesthetasc hairs. The slides were incubated for 10 min in PBS supplemented with 50 mM ammonium chloride. After blocking for one hour with 1% gelatin in PBS, the sections were incubated overnight with primary antibody diluted in 1% gelatin in PBS and then washed in PBS. The sections were then incubated with fluorescently-labeled secondary antibodies in 1% gelatin in PBS and then washed with PBS. The slides were mounted with Fluormount (Southern Biotechnology, Birmingham, AL, USA) and visualized with a 60x oil immersion lens.

Lipid extraction and detection

Olfactory sensilla were transferred to ice cold PI3K buffer (50 mM HEPES, pH 7; 25 mM MgCl2; 250 µM ATP; 50 mM DTT) and homogenized. The preparations were centrifuged for 5 minutes at 4°C at 800 g to pellet the solid debris, and the supernatants containing the outer dendritic membranes were divided equally resulting in an equivalent of 2 noses per 100 µl sample. The samples were stimulated at room temperature for 0, 1 and 10 seconds by pipetting 2 µl of TetraMarine (TetraWerke, Melle, Germany) extract into each sample resulting in a final concentration of 0.5 mg/mL. In some cases, 2 µl of Panulirus saline (PS) solution containing (in mM): 486 NaCl, 5 KCl, 13.6 CaCl2, 9.8 MgCl2, 10 HEPES at pH 7.9 was applied as a negative control. Reactions were stopped at the indicated time after addition of the odorant by denaturation and inhibition of the protein enzymes by pipetting 1 ml ice cold 0.5 M trichloroacetic acid into each sample and then freezing the samples on dry ice. PIP3 was then extracted and detected using a protein lipid overlay assay kit from Echelon Biosciences (Salt Lake City, UT, USA) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Blots were incubated with ECL detection reagent (Millipore), and the signal captured with a CCD camera (Fluor-S, BioRad). The signal strength correlates with PI levels in lipid extracts and was determined using MultiAnalyst software (BioRad). Specificity and range of detection of the assay was tested with a dilution series of PIP3 from 20 to 0.5 pmol, as well as with a panel of PIs including 20 pmol PI, PI(3)P, PI(4)P, PI(5)P, PI(3,4)P2, PI(3,5)P2, and P(4,5)P2.

Electrophysiological recordings of ORNs in situ

Electrophysiological experiments were performed as previously described (Bobkov, 2006). Briefly, a single annulus was excised from the lateral olfactory filament and the cuticle partially removed. The ORN somata were cleaned in Ca2+-free PS with trypsin (1 mg/mL, Sigma) followed by PS. The outer dendrites were superfused with PS, PS + PI3K inhibitor or PS + odorant. The cell bodies were continuously superfused with PS to restrict the application of the drug and odorants to the hairs. The odorant consisted of an aqueous extract of krill (San Francisco Bay Brand, Inc. USA) which was diluted in PS to a maximum concentration of 0.5 mg/mL prior to each experiment. Odorant was delivered with a stepper motor (Haydon Switch and Instruments Inc.) controlled by a fast-step SF-77B perfusion system (Warner Instruments Corporated) and pClamp 9.0 software (Molecular Devices). Pulse duration (40–800ms) was used to regulate odorant intensity. The PI3K inhibitors were prepared as stock solutions in DMSO and diluted in PS prior each experiment. Action potentials (APs) were recorded in the cell-attached loose-patch configuration at room temperature (~21°C) using an Axopatch 200A amplifier controlled through a Digidata 1322A interface using pClamp 9.0. Data were sampled at 5 kHz and analyzed with Clampfit 9.0 (Molecular Devices). AP frequency was calculated over the 2 s interval following stimulation. Dose/response curves were fit to the Hill equations: F(x) = Fmax*xh/(x1/2h+xh) for activation, or F(x) = 1 − Fmax*xh/(x1/2h+xh) for inhibition, where F is frequency of APs, x is the odorant or drug concentration, x1/2 is the half-effective odorant or drug concentration, and h is the Hill coefficient. Results are expressed as means ± SE from n cells.

Results

The outer dendritic membranes of lobster ORNs express a PI3K protein that is antigenically similar to PI3Kγ

A panel of antibodies against the catalytic subunits of the four mammalian class I isoforms of PI3K, including α, β, δ, and γ, were screened by western blot against outer dendrite membrane proteins collected from lobster olfactory sensilla (aesthetascs). Of the antibodies tested, only an anti-PI3Kγ antibody recognized an approximately 110 kDa band, which was enriched in the outer dendrite membranes compared to the remainder of the olfactory organ (Fig. 1). This band is the same molecular weight as that previously detected with an anti-PI3K (pan) non-isoform specific antibody (Zhainazarov et al. 2001) in lobster ORN outer dendrites and is similar in size to mammalian PI3Ks, which have predicted molecular weights ranging from 119 to 126 kDa and apparent molecular weights of approximately 110 kDa. An additional higher molecular weight band is present in the protein from the remainder of the olfactory organ, but its identity is currently unknown.

Figure 1. A PI3K protein antigenically similar to PI3Kγ is expressed in lobster ORN outer dendrites.

Western blot detection of the 110 kDa catalytic subunit of PI3K in outer dendrites (D) located in lobster olfactory sensilla and in olfactory tissue including ORN soma remaining after sensilla removal (S) with an anti-PI3Kγ antibody. MagicMark (Invitrogen) was used as a molecular weight marker (M). For each sample approximately 25 µg of protein was loaded per well. Western blot was probed with an anti-PI3Kγ antibody (R&D MAB2999), followed by a HRP-conjugated secondary antibody, and was then visualized by ECL image capture with a Fluor-S imager (BioRad). An arrow indicates the putative lobster PI3K.

The PI3K signal was further localized to the outer dendrites by immunocytochemistry. Immunoreactivity with the PI3Kγ antibody was found in cross-sections made through the distal 50% of the aesthetascs, which contain only outer dendrites (Fig. 2). Anti-PI3Kγ labeling was detected in the outer dendrite tissue within the autofluorescent cuticles and no PI3Kγ labeling is apparent in the absence of the primary antibody. As a positive control, the sections were co-labeled with an anti-PAIH antibody that recognizes a spiny lobster I(h) channel previously shown to be present in the outer dendrites (Gisselmann et al. 2005). No PI3K labeling was detected when there was no anti-PAIH signal, as would be the case if the outer dendrite tissue was absent from the cuticle. Together with the western blots, these data suggest that a PI3K protein antigenically similar to the catalytic subunit of the mammalian PI3Kγ isoform is expressed in the outer dendrites of lobster ORNs.

Figure 2. A lobster PI3K co-localizes with I(h) in the distal 50% of lobster olfactory aesthetasc hairs.

Detection of PI3K and I(h) by immunocytochemistry in cross-sections of lobster olfactory sensilla (aesthetasc hairs) with anti-PI3Kγ (R&D MAB2999) and anti-PAIH antibodies (Gisselmann et al. 2005). The anti-PI3Kγ antibody (green) labels the outer dendrite tissue within the auto-fluorescent cuticle. The labeling co-localizes with detection of I(h) (red). In the absence of primary antibody, no labeling of the outer dendrite tissue is detected. Bright field image shows the distribution of the outer dendrites within the cuticle.

Two class I PI3Ks can be cloned from the lobster olfactory organ

In order to further characterize lobster PI3K expression, we used homology-based cloning to search for PI3K genes expressed in olfactory tissue. Although there are four mammalian class I catalytic subunits for PI3K, insect express only one class I isoform and two can be identified in crustacean EST databases. Two class I PI3K sequences were found in a spiny lobster olfactory cDNA library using degenerate primers targeted to conserved regions of the two known crustacean PI3Ks. The first sequence was named splp110a, for spiny lobster p110a, due to its amino acid homology with the mammalian PI3Kα isoform. The second sequence was named splp110b, for spiny lobster p110b, and has strongest amino acid homology with the mammalian PI3Kβ isoform. The full length sequences were deposited in the GenBank database with accession number XXXXX for splp110a and XXXXX for splp110b and translated into predicted protein sequences (supplementary Fig. 1). Splp110a contains a putative coding region of 3096 base pairs that encodes 1032 amino acids with a predicted molecular weight of 118 kDa. Slp110b contains a putative coding region of 3224 base pairs that encodes 1074 amino acids with a predicted molecular weight of 124 kDa. Sequences were established as full length by the identification of upstream and terminating stop codons, an ATG start codon, and a poly-A tail.

Similar to other class I PI3Ks, both translated lobster PI3K protein sequences are predicted to encode ras binding and C2 domains, PI3K catalytic and accessory regions, and a regulatory subunit heterodimerization domain (supplementary Fig. 1). The translated amino acid sequence predicted by splp110a, PI3Ka, is 92% similar to the protein sequence predicted by a Homarus americanus EST. The translated amino acid sequence predicted by splp110b, PI3Kb, is 97% similar to the protein sequence predicted by another Homarus americanus EST. Compared to the rat PI3K isoforms, spiny lobster PI3Ka has the highest level of similarity of 45% with the α isoform and the lowest level of similarity of 27% with the γ isoform, while spiny lobster PI3Kb has the highest level of similarity of 42% with the β isoform and the lowest level of similarity of 28% with the γ isoform. PI3Ka is 30% similar and PI3Kb is 41% similar to the Drosophila p110 PI3K catalytic subunit.

Expression of lobster PI3Ks can be localized to the olfactory tissue

We attempted to localize the expression of the lobster PI3K p110 genes by in situ hybridization, but the mRNA levels appear to be below the threshold that can be reliably detected (data not shown). As an alternative, RT-PCR was used to test for mRNA expression in individual clusters of ORNs dissected from lobster olfactory tissue. While mRNA from both PI3K genes can be detected in total olfactory tissue, only splp110b can be detected in single isolated ORN clusters (5 out of 6 tested; Fig. 3). The PAIH gene encoding a member of the I(h)-channel family previously shown to be expressed in spiny lobster ORNs (Gisselmann et al. 2005) was detected in all ORN clusters (6 out of 6) tested, as well as in total olfactory tissue. None of the gene fragments were amplified from RNA in the absence of RT or template (data not shown).

Figure 3. Expression of the lobster PI3K splp110b gene can be detected in isolated lobster ORN clusters.

Total RNA from isolated lobster ORN clusters (IC) and total olfactory tissue (T) was used to prepare cDNA for PCR amplification of gene specific fragments with splp110a and splp110b specific primers. I(h) primers were used as a positive control and untranscribed RNA (N) was used as a negative control.

Lobster PI3K co-immunoprecipitates with Gα and Gβ

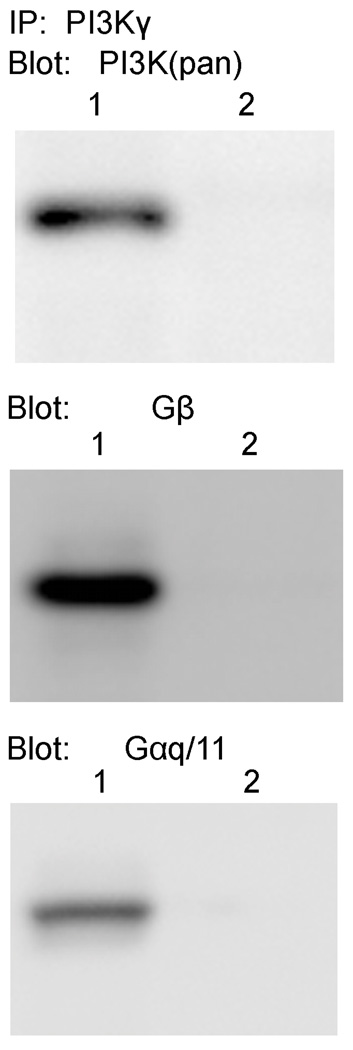

To test whether the lobster PI3K protein may be activated by G proteins, we looked for an interaction with both of the Gα and Gβ subunits previously shown to be present in lobster olfactory tissue (Xu et al. 1997; Xu et al. 1998; Xu et al. 1999; Xu and McClintock 1999). As shown in Figure 4, both G protein subunits can be co-immunoprecipitated with the lobster PI3K protein from the outer dendrite membranes using the anti-PI3Kγ antibody. No proteins were detected in the absence of the precipitating antibodies. As a control, the total amount of PI3K in the samples was detected with an anti-PI3K(pan) antibody. These results indicate that the lobster PI3K and G protein subunits are part of a complex in the outer dendritic compartment of lobster ORNs.

Figure 4. Gα and Gβ co-immunoprecipitate with lobster PI3K. PI3K was immunoprecipitated from lobster olfactory sensilla protein with (lane 1) an anti-PI3Kγ antibody (R&D MAB2999) or (lane 2) no antibody.

Eluted proteins were blotted and then detected with polyclonal antibodies against Gαq/11 (left panel) and Gβ. The top panel shows the amount of PI3K that could be detected in the samples with an anti-PI3K(pan) antibody (Santa Cruz I-19).

Odorants activate PI3K activity in the outer dendritic membranes in vitro

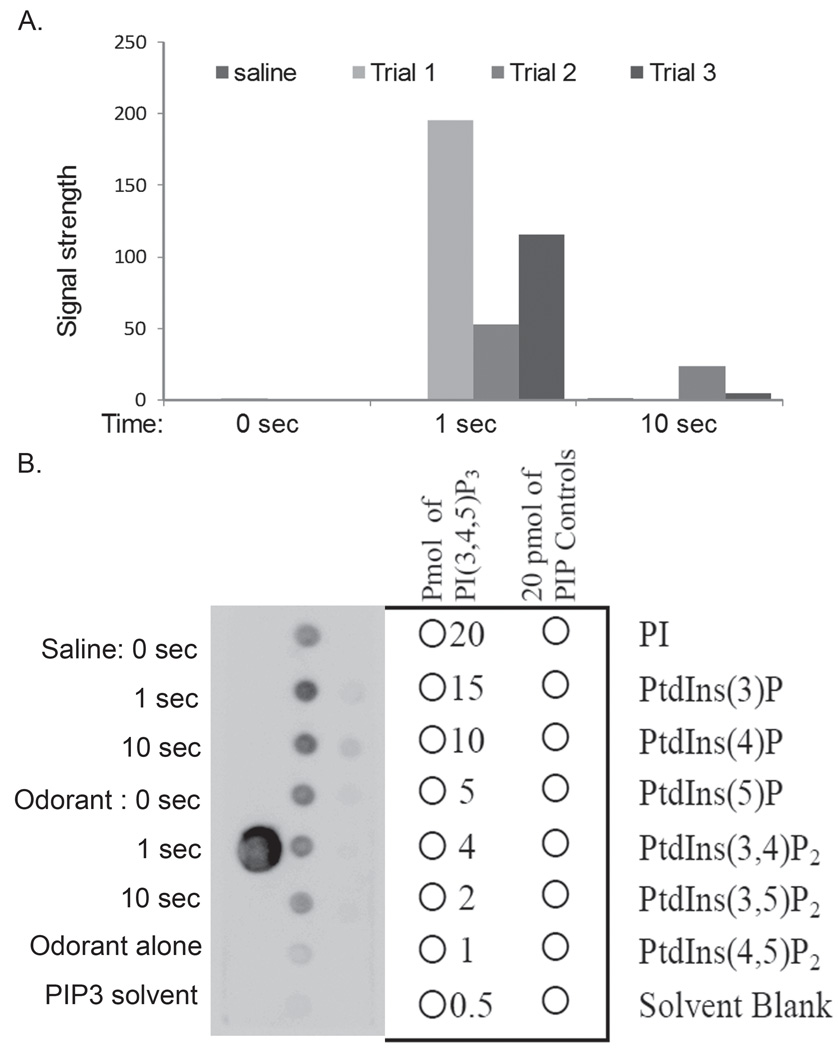

As PIP3 is one of the primary products of PI3K activation in vivo, we tested for an odorant-dependent change in PIP3 in the transduction compartment of lobster ORNs. To determine if PIP3 can be detected in lobster tissue, lipids were extracted from odorant-treated outer dendrites membranes of lobster ORNs. PIP3 was detected using a protein-lipid overlay assay (PIP3 Mass Strip Kit; Echelon Biosciences), which uses the pleckstrin homology domain of the protein Grp1 as a probe for PIP3. As shown in Figure 5, in three independent trials a transient increase in PIP3 was detected in phospholipids extracted from the outer dendrites of lobster ORNs. Odorants were applied to the olfactory outer dendrite membranes for 0, 1 and 10 sec, and then the enzymatic reactions in the samples were stopped at the indicated time. As would be expected based on the low levels of the lipid in resting cells, PIP3 was undetectable at the 0 sec time point. A PIP3 signal was detectable in the membrane extracts after 1 sec of incubation with the odorant, but returned to an undetectable level at 10 sec. The differences among the magnitudes of the PIP3 signal in the three trials likely reflects variations is tissue load due to the lack of uniformity in wild caught animals, as well as the limitations of manually applying the odorant and stopping the reaction. As a negative control, no increase was detected in samples treated in parallel with the saline solution used to dilute the odorant treatment. The assay was shown to be sensitive to as little as 0.5 pmol of synthetic PIP3 and there was little cross reactivity with the other PIs tested. No signal was detected in the PIP3 solvent or in the odorant extract in the absence of outer dendrite membranes.

Figure 5. PIP3 increases in in vitro extracts prepared from lobster olfactory outer dendritic membranes in response to odorant stimulation.

(A) PIP3 was detected by overlaying the membrane with a lipid binding protein consisting of the pleckstrin homology domain from GRP1 fused with GST using a PIP3 Mass Strip Kit (Echelon Biosciences). Lipids were extracted from dendritic membrane preparations at the time indicated after treatment with odorant and spotted onto a nitrocellulose membrane. Results are presented for three independent trials of odorant treatment and a single control in which the membrane preparation was treated with the odorant carrier (saline). Blots were visualized by ECL image capture with a Fluor-S imager (BioRad). Signal strength (in arbitrary units) was determined by densitometry. Solvent blank is subtracted from signal. (B) Representative blot including odorant and saline treated samples (left column). Additional controls include a PIP3 solvent blank and odorant alone. Middle and right columns: Specificity and range of detection of the assay was tested with a dilution series of PIP3 from 20 to 0.5 pmol, as well as with a panel of PIs including 20 pmol PI, PI(3)P, PI(4)P, PI(5)P, PI(3,4)P2, PI(3,5)P2, and P(4,5)P2. Additional controls include a PIP3 solvent blank and odorant alone.

PI3Kβ and γ inhibitors block the odorant-evoked discharge of lobster ORNs in situ

Since pan-specific inhibitors of PI3K, Wortmannin and LY294002 (Kong and Yamori, 2008; Hawkins et al. 2006) can suppress the receptor potential in lobster ORNs (Zhainazarov et al. 2001), we tested whether isoform specific inhibition would have a similar effect (Fig. 6A, top panel). Not all known PI3K isoform-specific inhibitors are likely to be effective because the reported specificity of the drugs is based on their interaction with mammalian PI3Ks, which does not necessarily translate to an ability to interact with the lobster PI3Ks. Based on these limitations, a panel of membrane permeable (logD 0.24–3.22, pH8.0), ATP-competitive PI3K inhibitors were tested on conventional phaso-tonic ORNs, including: PI3Kγ inhibitor AS604850, Camps et al., 2005; PI3-kinase α Inhibitor 2, Hayakawa et al., 2006; PI3Kγ inhibitor AS605240, Camps et al., 2005; PI3Kβ inhibitor TGX-221, Jackson et al., 2005; PI3Kγ inhibitor AS-252424, Pomel et al., 2006). Overall, AS605240 and PI3-kinase α inhibitor 2 had little or no effect on the odorant-evoked activity of ORNs. The peak odorant response was 0.82 ± 0.06 Hz in control vs 0.84 ± 0.04 Hz in the presence of AS605240 (1mkM, p=0.86, n=3), and 0.97 ± 0.02 Hz in control vs 0.87 ± 0.07 Hz in the presence of PI3-kinase α inhibitor 2 (50mkM, p=0.15, n=7). Three of the inhibitors, including the γ specific AS604850 and AS-252424, as well as the β specific TGX-221, significantly suppressed the peak odorant response: 0.96 ± 0.02 Hz vs 0.55 ± 0.06 Hz; 0.96 ± 0.01 Hz vs 0.42 ± 0.06 Hz; and 0.99 ± 0.01 Hz vs 0.85 ± 0.02 Hz in control vs AS604850 (30mkM, p<0.05, n=6), AS-252424 (20mkM, p<0.05, n=24), and TGX-221 (5.5mkM, p<0.05, n=5), respectively. The inhibition was reversible within 10 min.

Figure 6. AS-252424 blocks the odorant-evoked discharge of lobster ORNs in situ.

A. Raster displays of action potentials (APs) from a single lobster ORN recorded in the loose-patch configuration evoked by increasing intensities of odorant denoted by increasing duration of application (duration, 60–300 ms, with increment 20 ms, shortest duration at the top of each block) shown before, during (shaded), and following treatment with 20 µM AS-252424. B. Plot of the normalized evoked AP discharge frequency of the same ORN as in A plotted as a function of odorant intensity (duration, 60–300 ms) before, during and following treatment with 20 µM of AS-252424. Solid line through the points indicates the fit of the Hill equation. Note: AS-252424 reversibly blocked the output of the ORN. C. Raster displays of APs from another single ORN evoked by a fixed duration of odorant (200 ms) and inhibited by increasing concentrations of the drug (shaded displays). D. Plot of the normalized evoked AP discharge frequency of this (gray circles) and all 24 (black circles) ORNs so tested as a function of drug concentration. Solid line through the points indicates the fit of the Hill equation. Note the considerable variability of the effect of the drug. Inset: Bar histogram plot of the average of 10 responses of the cell shown in C to odorant before (light gray bars) and following (dark gray bars) treatment with 10 µM AS-252424 as a function of discharge time. Note: AS-252424 noticeably decreases the kinetics as well as the peak response.

The effect of AS-252424 (20 µM) was studied in more detail. In addition to inhibiting the odorant-evoked response in 23 of 31 (74%) cells tested (Fig. 6), AS-252424 also inhibited the spontaneous discharge from 1.36 ± 0.27 Hz prior to treatment to 0.95 ± 0.2 Hz following treatment (n=26, Fig. 7A). The effect of AS-252424 varied considerably among ORNs (e.g. Fig. 6A vs C). AS-252424 inhibited the response to the range of odorant concentrations tested (Fig. 6A, B) rather than shifting the sensitivity of the ORNs to the odorant. Increasing concentrations of the drug gradually decreased the amplitude of the response to repeated odorant stimulation in a concentration-dependent manner (Fig. 6C, D). For the cell shown (Fig. 6C), the apparent affinity of the drug was about 5.5 µM with a cooperativity coefficient (h) of approximately 2 (Fig. 6D). Overall, the concentration-inhibition function for 24 ORNs was 11µM, with h approximately 0.7. In addition to decreasing the peak response the drug also induced a reversible change in the kinetics of the response (Fig. 6D, inset), reducing the rise time to half-amplitude by 0.42 ± 0.08 s (n=25).

Discussion

Among the mammalian class I isoforms of PI3K both γ and β couple are activated by G proteins in mammalian cells (Stephens et al. 1996; Murga et al. 2000), and thus could potentially play a role in olfactory signal transduction. The lobster olfactory PI3K can be detected in the outer dendrites with an antibody against rat PI3Kγ and this antigenic similarity is consistent with the possibility that the lobster protein also couples through G proteins. However, despite this similarity, the lobster PI3Ks cloned from olfactory tissue are predicted to have the strongest overall amino acid sequence identity with the mammalian α and β isoforms rather than the γ isoform. Of the two isoforms, only splp110b could be detected in clusters of ORNs isolated from the olfactory tissue. The protein predicted to be encoded by the splp110b, has strongest homology with the mammalian PI3Kβ isoform and Drosophila class I PI3K, both of which are known to be activated by GPCRs (Murga et al. 2000; Howlett et al. 2008). At this time, it is not known if the PI3Kγ antibody interacts with lobster PI3Kb, nor has the epitope recognized by the antibody been identified. However, based on its homology to a GPCR-coupled isoform of PI3K and localization of its expression to ORNs, we speculate that lobster PI3Kb is likely to be the PI3K involved in olfactory transduction in lobster ORNs. Consistent with the antigenic similarity of the lobster ORN with PI3Kγ and its amino acid homology with PI3Kβ, the odorant response was blocked with inhibitors against the both of the GPCR-activated mammalian PI3K isoforms, β and γ. Because the specificity of the drugs is based on specific interactions with ATP binding sites of the mammalian isoforms, these results support our evidence that the lobster olfactory PI3K may have structural similarities with both of the known GPCR-activated mammalian PI3Ks.

G protein coupling of the lobster olfactory PI3K is further supported by our finding that the lobster olfactory PI3K protein appears to be in a complex with both the Gα and Gβ subunits. Co-immunoprecipitation is unable to discriminate between direct and indirect protein interaction, and it is possible that similar to the GPCR-coupled mammalian PI3Ks (Voigt et al. 2005), interaction is mediated indirectly through the regulatory subunit of PI3K. A potential function of the Gβ subunit expressed by lobster ORNs is to recruit proteins to the plasma membrane of the outer dendrites to transmit the odor detection information to biochemical signaling pathways (Xu et al. 1998). As one characteristic of PI3K activation is an increased association with the cell membrane (Qin and Chock 2003), a possible function of the interaction between the Gβγ subunits and the lobster PI3K protein maybe recruitment of the enzyme to the cell membrane for odorant-evoked activation. In contrast, interaction between Gα and PI3Ks in mammalian cells is thought to inhibit PI3K activation (Ballou et al. 2006), and thus the interaction between the Gα subunit and the lobster PI3K protein may play a role in suppressing spontaneous activation of enzymatic activity. If this is the case, G protein activation induced by conformational changes in the structure of the lobster olfactory receptor upon ligand binding could allow PI3K activation by either releasing Gα from the complex or altering its interaction with Gβγ as has been described for PLC (Wang et al. 2009).

PI3Ks mediate a diverse array of cellular functions and in order to implicate PI3K activity in olfactory transduction, it is important not just to show the protein occurs in the transduction compartment, but that it can be activated by odorants sufficiently fast to mediate transduction. PIP3 is the primary product of PI3K activity in vivo and changes in its level can be used as a reliable measure of PI3K activation (Guillou et al. 2007). Consistent with a role for PI3K in olfactory transduction, we found constitutively low levels of PIP3 in extracts of lobster outer dendritic membranes that rapidly increased in response to odorant stimulation. PI3K activation could be detected after 1 sec of incubation with odorant, but given the limitations of the manual application system, it is likely that the production of PIP3 begins earlier than 1 sec, consistent with a response time of the cells to odorants in situ being several hundred milliseconds. These results indicate that not only is PI3K present in the appropriate location for involvement in lobster olfactory signal transduction, but that it is in an catalytically active form that can be stimulated by odorant treatment. The following reduction in the level of PIP3 that occurs by 10 sec is likely the result of endogenous phosphatase activity in the samples. In mammalian systems, the phosphatase PTEN rapidly dephosphorylates PIP3 to terminate PI3K signaling (Maehama and Dixon 1998) and a similar phosphatase may act in the outer dendrites of lobster ORNs.

Consistent with our evidence that PI3K can be activated sufficiently fast in vitro to account its potential role in transduction, AS-252424, a selective inhibitor for the γ isoform of mammalian PI3K, eliminated the fast transient response in a majority of the ORNs tested. Although the possibility that PI3K is expressed only in a subset of cells cannot be excluded, it is likely that not all cells were affected by the inhibitor due to limited access of the drug to the outer dendrites, which are contained inside a semi-porous cuticle. The finding that AS-252424 inhibits both the spontaneous and evoked activity of the cells could suggest that AS-252424 acts non-specifically. However, we have ruled out the possibility that AS-252424 inhibits the odorant-evoked response by blocking the lobster SGC channel (data not shown). The SGC channel amplifies the primary olfactory transduction downstream from PI3K and is thought to be the channel regulated by PIP3 (Zhainazarov and Ache 1999; Zhainazarov et al. 2001). The effects of AS-252424 on spontaneous ORN activity may instead reflect inhibition of a low level of constitutive activity of PI3K, high enough to support ion transport system activity in close vicinity of signaling complexes but insufficient to bring total PIP3 concentration to a detectable level.

Collectively, our findings make a compelling argument for the involvement of a PI3K coupled via G protein activation in lobster olfactory transduction. While odorants can rapidly and transiently change the levels of PIP3, the product of PI3K activation in vivo, sufficiently fast to account for the rapid, transient odor-evoked electrophysiological output of the ORNs, the exact role of PIP3 in the activation of lobster ORNs has yet to be determined. Since exogenous PIP3 activates and modulates the lobster SGC channel (Zhainazarov et al. 2001), it is possible that endogenously produced PIP3 activates this channel and/or an IP3R expressed in these cells. Given that the catalytic subunits of PI3Kβ and γ as well as odorant-dependent PI3K activity can be detected in the cilia of rodent ORNs (Ukhanov et al. 2009, submitted; Klasen et al. 2010), PI3K-mediated signaling may play a role in olfactory signal transduction across species.

Supplementary Material

Table 1. Comparison of PI3K sequences.

Percent sequence identity of the lobster PI3Ka and PI3Kb proteins with PI3Ks of other species including rat PI3Kα, -β,-δ, and –γ, as well as Drosophila p110 and partial sequences from Homarus americanus PI3Ka and b. Sequences include: rat PI3Kα (accession number XP_001059350), rat PI3Kβ (accession number NP_445933), rat PI3Kγ (accession number NP_001100193), rat PI3Kδ (accession number NP_001102448), Drosophila p110 (accession number NM_142645), Homarus PI3Ka (accession number EX471505), and Homarus PI3Kb (accession number FF278128). Percent sequence identity is based on ClustalW (http://www.clustal.org/) pair-wise sequence comparisons.

| Homolog | Lobster PI3Ka | Lobster PI3Kb |

|---|---|---|

| Rat PI3Kα | 45 | 36 |

| Rat PI3Kβ | 36 | 42 |

| Rat PI3Kγ | 27 | 28 |

| Rat PI3Kδ | 35 | 41 |

| Drosophila p110 | 30 | 41 |

| Homarus PI3Ka | 92 | 47 |

| Homarus PI3Kb | 53 | 97 |

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Paul Nielsen at Echelon Biosciences as well as Ms. Anna Mistretta-Bradley and Dr. David Price for technical assistance. This research was supported by the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders through awards R01 DC001655 (BWA) and F32 DC009730 (EAC).

Abbreviations used

- AP

Action potentials

- CNG

cyclic nucleotide gated

- GPCR

G protein-coupled receptor

- IP

immunoprecipitation

- OE

olfactory epithelium

- ORN

olfactory receptor neuron

- PS

Panulirus saline

- PBS-T

phosphate buffered saline-Tween 20

- PIP2

phosphatidylinositol (4,5)-bisphosphate

- PIP3

phosphatidylinositol (3,4,5)-trisphosphate

- PI

phosphoinositide

- PI3K

phosphoinositide 3-kinase

- PLC

phospholipase C

- SPB

Sörenson phosphate buffer

- TRP

transient receptor potential

- VNO

vomeronasal organ

Footnotes

Disclosure/ Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest

References

- Ballou LM, Chattopadhyay M, Li Y, Scarlata S, Lin RZ. Galphaq binds to p110alpha/p85alpha phosphoinositide 3-kinase and displaces Ras. Biochem J. 2006;394:557–562. doi: 10.1042/BJ20051493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benton R, Vannice KS, Gomez-Diaz C, Vosshall LB. Variant ionotropic glutamate receptors as chemosensory receptors in Drosophila. Cell. 2009;136:149–162. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chouquet B, Debernard S, Bozzolan F, Solvar M, Maibeche-Coisne M, Lucas P. A TRP channel is expressed in Spodoptera littoralis antennae and is potentially involved in insect olfactory transduction. Insect Mol Biol. 2009;18:213–222. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2583.2008.00857.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fadool DA, Ache BW. Plasma membrane inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate-activated channels mediate signal transduction in lobster olfactory receptor neurons. Neuron. 1992;9:907–918. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(92)90243-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fadool DA, Estey SJ, Ache BW. Evidence that a Gq-protein mediates excitatory odor transduction in lobster olfactory receptor neurons. Chem Senses. 1995;20:489–498. doi: 10.1093/chemse/20.5.489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gisselmann G, Marx T, Bobkov Y, Wetzel CH, Neuhaus EM, Ache BW, Hatt H. Molecular and functional characterization of an I(h)-channel from lobster olfactory receptor neurons. Eur J Neurosci. 2005;21:1635–1647. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2005.03992.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guillou H, Lecureuil C, Anderson KE, Suire S, Ferguson GJ, Ellson CD, Gray A, Divecha N, Hawkins PT, Stephens LR. Use of the GRP1 PH domain as a tool to measure the relative levels of PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 through a protein-lipid overlay approach. J Lipid Res. 2007;48:726–732. doi: 10.1194/jlr.D600038-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollins B, Hardin D, Gimelbrant AA, McClintock TS. Olfactory-enriched transcripts are cell-specific markers in the lobster olfactory organ. J Comp Neurol. 2003;455:125–138. doi: 10.1002/cne.10489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howlett E, Lin CC, Lavery W, Stern M. A PI3-kinase-mediated negative feedback regulates neuronal excitability. PLoS Genet. 2008;4:e1000277. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kain P, Chakraborty TS, Sundaram S, Siddiqi O, Rodrigues V, Hasan G. Reduced odor responses from antennal neurons of G(q)alpha, phospholipase Cbeta, and rdgA mutants in Drosophila support a role for a phospholipid intermediate in insect olfactory transduction. J Neurosci. 2008;28:4745–4755. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5306-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaupp UB, Seifert R. Cyclic nucleotide-gated ion channels. Physiol Rev. 2002;82:769–824. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00008.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klasen K, Corey EA, Kuck F, Wetzel CH, Hatt H, Ache BW. Odorant-stimulated phosphoinositide signaling in mammalian olfactory receptor neurons. Cell Signal. 2010;22:150–157. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2009.09.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liman ER, Corey DP, Dulac C. TRP2: a candidate transduction channel for mammalian pheromone sensory signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:5791–5796. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.10.5791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin W, Margolskee R, Donnert G, Hell SW, Restrepo D. Olfactory neurons expressing transient receptor potential channel M5 (TRPM5) are involved in sensing semiochemicals. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:2471–2476. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0610201104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maehama T, Dixon JE. The tumor suppressor, PTEN/MMAC1, dephosphorylates the lipid second messenger, phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-trisphosphate. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:13375–13378. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.22.13375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munger SD, Gleeson RA, Aldrich HC, Rust NC, Ache BW, Greenberg RM. Characterization of a phosphoinositide-mediated odor transduction pathway reveals plasma membrane localization of an inositol 1,4, 5-trisphosphate receptor in lobster olfactory receptor neurons. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:20450–20457. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M001989200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murga C, Fukuhara S, Gutkind JS. A novel role for phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase beta in signaling from G protein-coupled receptors to Akt. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:12069–12073. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.16.12069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin S, Chock PB. Implication of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase membrane recruitment in hydrogen peroxide-induced activation of PI3K and Akt. Biochemistry. 2003;42:2995–3003. doi: 10.1021/bi0205911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato K, Pellegrino M, Nakagawa T, Nakagawa T, Vosshall LB, Touhara K. Insect olfactory receptors are heteromeric ligand-gated ion channels. Nature. 2008;452:1002–1006. doi: 10.1038/nature06850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephens L, Hawkins PT, Eguinoa A, Cooke F. A heterotrimeric GTPase-regulated isoform of PI3K and the regulation of its potential effectors. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 1996;351:211–215. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1996.0018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ukhanov K, Corey EA, Brunert D, Klasen K, Ache BW. Phosphoinositide-3-kinase mediated signalling inhibits the rapid output of mammalian olfactory receptor neurons. 2009 submitted. [Google Scholar]

- Voigt P, Brock C, Nurnberg B, Schaefer M. Assigning functional domains within the p101 regulatory subunit of phosphoinositide 3-kinase gamma. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:5121–5127. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M413104200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Golebiewska U, Scarlata S. A self-scaffolding model for G protein signaling. J Mol Biol. 2009;387:92–103. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2009.01.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wicher D, Schafer R, Bauernfeind R, Stensmyr MC, Heller R, Heinemann SH, Hansson BS. Drosophila odorant receptors are both ligand-gated and cyclic-nucleotide-activated cation channels. Nature. 2008;452:1007–1011. doi: 10.1038/nature06861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu F, McClintock TS. A lobster phospholipase C-beta that associates with G-proteins in response to odorants. J Neurosci. 1999;19:4881–4888. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-12-04881.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu F, Bose SC, McClintock TS. Lobster G-protein coupled receptor kinase that associates with membranes and G(beta) in response to odorants and neurotransmitters. J Comp Neurol. 1999;415:449–459. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9861(19991227)415:4<449::aid-cne3>3.0.co;2-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu F, Hollins B, Landers TM, McClintock TS. Molecular cloning of a lobster Gbeta subunit and Gbeta expression in olfactory receptor neuron dendrites and brain neuropil. J Neurobiol. 1998;36:525–536. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4695(19980915)36:4<525::aid-neu6>3.0.co;2-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu F, Hollins B, Gress AM, Landers TM, McClintock TS. Molecular cloning and characterization of a lobster G alphaS protein expressed in neurons of olfactory organ and brain. J Neurochem. 1997;69:1793–1800. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1997.69051793.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhainazarov AB, Ache BW. Effects of phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate and phosphatidylinositol 4-phosphate on a Na+gated nonselective cation channel. J Neurosci. 1999;19:2929–2937. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-08-02929.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhainazarov AB, Doolin R, Herlihy JD, Ache BW. Odor-stimulated phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase in lobster olfactory receptor cells. J Neurophysiol. 2001;85:2537–2544. doi: 10.1152/jn.2001.85.6.2537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.