Abstract

Tumor necrosis factor (TNF)–related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL) is a member of the TNF family of cytokines and has been shown to induce cell death in many types of tumor and transformed cells but not in normal cells. This tumor-selective property has made TRAIL a promising candidate for the development of cancer therapy. However, safety issues are a concern because certain preparations of recombinant TRAIL protein were reported to induce toxicity in normal human hepatocytes in culture. In addition, previous studies on tumor selectivity of exogenous TRAIL protein were carried out in xenograft models, which do not directly address the tumor selectivity issue. It was not known whether exogenous or overexpression of TRAIL in a syngeneic system could induce tumor cell death while leaving normal tissue cells unharmed. Thus, the tumor selectivity of TRAIL-induced apoptosis remains to be further characterized. In our study, we established mice that overexpress TRAIL by retroviral-mediated gene transfer in bone marrowcells followed by bone marrow transplantation. Our results show that TRAIL overexpression is not toxic to normal tissues, as analyzed by hematologic and histologic analyses of tissue samples from TRAIL-transduced mice. We show for the first time that TRAIL overexpression in hematopoietic cells leads to significant inhibition of syngeneic tumor growth in certain tumor lines. This approach may be used further to identify important molecules that regulate the sensitivity of tumor cells to TRAIL-induced cell death in vivo.

Introduction

Three mechanisms are currently known by which lymphocytes deliver cell-mediated cytotoxicity to target cells, such as viral-infected and tumor cells. These include Fas receptor-mediated apoptosis (1), perforin-granzyme–mediated cytotoxicity (2), and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)–related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL)–mediated apoptosis (3, 4). TRAIL, also known as Apo-2 ligand, is a type II membrane protein belonging to the TNF family of cytokines (5, 6). Members of the TNF family of cytokines (Fas, TNF, and TRAIL) have attracted considerable attention over the past decade for their antitumor effect. Unlike TNF and Fas ligand (FasL), which can cause life-threatening toxic effects when used systemically (7, 8), recombinant TRAIL protein has been shown to induce cell death in many types of tumor and transformed cells, but not in normal cells, in culture and xenograft animal models (5, 6, 9, 10). Those discoveries have allowed TRAIL to stand out from other members of TNF family of cytokines and hold great potential for TRAIL to be a promising candidate for antitumor therapeutic development. Recently, human agonist antibodies to TRAIL receptors 1 and 2 have been tested for their antitumor efficacy, have shown promising results in xenograft models (11, 12), and have been currently used in clinical trials.

However, issues of safety and species specificity remain a concern because certain preparations of recombinant TRAIL protein have been reported to induce toxicity in normal human hepatocytes in culture (13). In addition, initial xenograft studies using recombinant human soluble forms of the TRAIL protein showed TRAIL-induced apoptosis of human cancer cells transplanted into immunodeficient mice without toxicity to the normal tissues of the mice bearing these xenograft tumors (9, 10). These studies do not directly address the tumor selectivity of TRAIL-induced apoptosis due to the fact that the human and mouse forms of TRAIL share only 65% amino acid sequence identity and thus may behave differently in vivo and also because human TRAIL does not kill mouse cells with the same efficacy as human cells (5, 6).3 An understanding of the potential toxicity of TRAIL is essential if it is to be used in clinical trials. Thus, the tumor selectivity of exogenous TRAIL in a syngeneic mouse system remains to be elucidated.

Unlike FasL and TNF, which have a restricted tissue distribution, TRAIL mRNA has been detected in a wide variety of tissues and cell types in humans and mice (5, 6). The functional expression of TRAIL protein has been observed on the surface of various immune cells that were previously known to induce apoptosis of target cells by an unidentified mechanism. These cells include natural killer (NK) cells, dendritic cells, monocytes, and T cells that have been stimulated by cellular transformation (14-19), indicating a contribution of endogenous TRAIL to cell-mediated toxicity toward tumor cells. However, in seeking antitumor approaches with TRAIL, it is also important to determine whether overexpression of TRAIL by immune cells in the body would generate increased antitumor activity while leaving normal tissue cells unharmed.

Our aim is to study the tumor selectivity of TRAIL in vivo. We opted for a syngeneic system because it removes the issues that could arise from differences in genetic background among the TRAIL protein, tumor cells, and host normal tissues in evaluating the potential toxicity of TRAIL. In our study, the full-length mouse TRAIL (mTRAIL) gene was transferred into mouse bone marrow cells by retroviral infection in vitro, and transduced bone marrow cells were transplanted into lethally irradiated mice of the same strain. The overexpression of TRAIL is limited to the hematopoietic cells of bone marrow recipient mice. We observed that overexpression of TRAIL could significantly inhibit syngeneic mouse tumor growth without causing a toxic effect on normal tissues in vivo. This model may be used further to study the in vivo effect of other molecules on the regulation of TRAIL-induced inhibition of tumor growth.

Materials and Methods

DNA constructs

The retroviral vector pMIG (a generous gift from Dr. David Baltimore, Caltech, Pasadena, CA) was constructed by subcloning internal ribosomal entry site (IRES) hGFP-3M from pCITE IRES hGFP-3M into the murine sarcoma virus 2.2 retroviral vector. The cDNA encoding the full-length mTRAIL was subcloned from the mTRAIL/pMKITNeo vector (a generous gift from Dr. Hideo Yagita, Juntendo University School of Medicine, Bunkyo-ku, Tokyo, Japan) into the pMIG vector to generate a pMIG/mTRAIL retroviral vector. The pCl3-EcotR vector encoding ecotropic glycoprotein was also obtained from Dr. David Baltimore.

Reagents

The rat anti-mTRAIL monoclonal antibody (mAb) N2B2, biotin-conjugated goat anti-rat Ig, streptavidin-phycoerythrin conjugate, and purified hamster anti-mouse Fas mAb (clone Jo2) were obtained from BD Biosciences PharMingen (San Diego, CA). Cleaved caspase-3 antibody was purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA). The growth factors murine interleukin (IL)-3, murine IL-6, and murine stem cell factor were supplied by PeproTech, Inc. (Rocky Hill, NJ). Sodium chromate was obtained from Amersham Pharmacia (Piscataway, NJ).

Cell culture

BOSC23, NIH3T3, and mouse fibrosarcoma L929 cells were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC; Rockville, MD) and maintained in DMEM containing 2 mmol/L glutamine, 50 units/mL penicillin, 50 Ag/mL streptomycin, 1 mmol/L pyruvate, and 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; BOSC23 cells) or 10% FCS (NIH3T3 cells) or 10% horse serum (L929 cells). Mouse plasmacytoma Ag8 cells (ATCC), mouse renal adenocarcinoma RENCA cells (20), and mouse B lymphoma 2PK-3 and mTRAIL/2PK-3 cell lines (21) were maintained in RPMI 1640 containing 50 units/mL penicillin, 50 μg/mL streptomycin, 1 mmol/L pyruvate, and 10% FCS. The mouse mammary carcinoma cell line EMT6 (22) was single-cell cloned to obtain EMT6.5. The mouse mammary carcinoma line 4T1.2 cell line has been described previously (23). These lines were maintained in a-MEM containing 2 mmol/L glutamine, 50 units/mL penicillin, 50 μg/mL streptomycin, 1 mmol/L pyruvate, and 10% (EMT6.5 cells) or 5% FCS (4T1.2 cells).

Retrovirus preparation

Retroviral supernatant was produced by transient transfection in 100-mm dishes, where 4 × 106 BOSC23 cells were plated in 10 mL of 10% FBS 16 hours before transfection. CaCl2 (100 μL, 1.25 mol/L) was added to 900 AL HEPES-buffered saline solution (pH 7.05) containing pCl3-EcotR and either pMIG or pMIG/mTRAIL DNA and allowed to remain at room temperature for 20 to 30 minutes. The DNA mix was then added to the above cell medium and incubated at 37°C (5% CO2) for 8 to 12 hours. The medium was then changed to 8 mL of fresh 10% FBS, and 48 to 72 hours later the medium was harvested. The harvested medium (retroviral supernatant) was filtered through a 0.45-μm filter, aliquotted, and stored immediately at –80°C. Determination of viral titer was done by infection of NIH3T3 cells with an aliquot of the retroviral supernatant and detection of green fluorescent protein (GFP)–positive cells by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) analysis (FACSCalibur, Becton Dickinson Immunocytometry System, San Jose, CA). Viral titer was calculated by multiplying the percentage of GFP-positive cells with the total number of cells on the dish and the dilution factor of retroviral supernatant and dividing by the total medium in the dish.

Bone marrow infection and transplantation

Bone marrow was isolated from femurs and tibias of 6- to 8-week-old BALB/c female mice 4 days after i.v. injection of 5-fluorouracil (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) at 150 mg/kg body weight. Bone marrow cells were prestimulated for 48 hours in Eagle's MEM (Stem Cell Technology, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada) containing 15% FBS, 2 mmol/L glutamine, 50 units/mL penicillin, 50 μg/mL streptomycin, 1 mmol/L pyruvate, 6 μg/mL murine IL-3, 10 μg/mL murine IL-6, and 100 μg/mL murine stem cell factor. Viable cells were counted and infected with retroviral stocks at a ratio of 5 × 106 to 1 × 107 retroviral particles/mL to 2 × 106 bone marrow cells. To increase infection efficiency, 1 mL retroviral stock was added to the cells next day. Forty-eight hours after infection, cells were replaced with fresh medium containing the same content, except retrovirus. GFP-positive cells were collected by FACS and washed with sterile PBS. Recipient female BALB/c mice were prepared by two doses of 450 rads γ-irradiation, with each dose given 4 hours apart. Transduced bone marrowcells were transplanted by i.v. injection of 0.5 × 106 cells in 0.2 mL PBS into the lateral tail vein.

Apoptosis assay

EMT6.5, 4T1.2, and L929 tumor cell lines, each at 2.5 × 105 cells, were grown in RPMI 1640 growth medium in the presence or absence of mTRAIL retroviral supernatant for 24 hours. The cells were replaced with RPMI 1640 growth medium for 3 days. The cells were detected by measuring the sub-G1 apoptotic cell population with propidium iodide (Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis, IN) at a final concentration of 50 μg/mL as described (24).

Flow cytometry for TRAIL

2PK-3 and mTRAIL/2PK-3 cells (1 × 106) were incubated with 1 μg rat anti-mTRAIL mAb N2B2 for 1 hour at 4°C followed by biotin-conjugated goat anti-rat Ig and then streptavidinphycoerythrin conjugate. After washing with PBS, the cells were analyzed by FACS, and data were processed by using the CellQuest program (Becton Dickinson Immunocytometry System).

Immunoblotting

For detection of mTRAIL protein in hematopoietic cells from mTRAIL-transduced mice, 1 month after bone marrow transplantation, peripheral whole-blood samples were obtained from the tail vein. RBCs were removed, and WBCs were incubated for 30 minutes at 4°C in lysis buffer (25). Lysates were cleared at 10,000 × g for 10 minutes at 4°C, and supernatant protein samples were resolved by SDS-PAGE and transferred to Immobilon membranes (Millipore, Bedford, MA). Immunoblot analysis was done with rat anti-mTRAIL mAb N2B2 as the primary antibody. The rest steps have been describe previously (24).

Cr release assay

51Cr-labeled target cells (1 × 104) and effector cells were mixed in U-bottomed wells of a 96-well microtiter plate at a 100:1 E:T ratio. After 8 to 16 hours of incubation, cell-free supernatants were collected and radioactivity was measured in a gamma counter. The percentage of specific 51Cr release was calculated as described previously (26).

RNA isolation and quantitative real-time PCR for TRAIL

Total RNA was isolated using the RNeasy Mini kit (Qiagen, Chatsworth, CA); 3 Ag for detection of mTRAIL were included in a 50-μL reaction containing 25 μL of 2× Taqman universal PCR master mix, 1.25 μL of 40× MultiScribe reverse transcriptase/RNase inhibitor mix (PE Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA), forward and reverse primers (900 nmol/L), fluorogenic Taqman probe (200 nmol/L), and RNase/DNase-free water. The thermal cycling conditions were 30 minutes at 48°C, an initial denaturation step for 10 minutes at 95°C, and 40 cycles at 95°C for 15 seconds and 60°C for 1 minute. Thermal cycling was done on an ABI Prism 7700 Sequence Detector (PE Applied Biosystems). Primers and probes were described previously (27).

Pathologic analysis

Beginning at 4 or 5 weeks after bone marrow transplantation, whole-blood samples and organs were collected from bone marrow recipient mice. Whole-blood cell counts were done at the Diagnostic and Comparative Pathology Laboratory of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (Cambridge, MA). Organ tissues were preserved in 10% formalin immediately after collection and processed into paraffin-embedded samples. Evaluation of apoptosis was done by the terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase–mediated dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL) assay as well as by cleaved caspase-3 staining on slides at the Rodent Histopathology Core Laboratory of the Dana-Farber/Harvard Cancer Center (Boston, MA). Morphology analysis of slides was carried out by H&E staining and microscopy.

Tumor growth in vivo experiment

The tumor cell inoculation method was described previously (26). Briefly, 1 month after bone marrow transplantation, EMT6.5 cells (1 × 105) were injected s.c. into the right flank. In some experiments, 4T1.2 cells (2.5 × 104) were injected into the right second upper mammary fat pad. Primary tumor growth was measured by using calipers in two dimensions. Tumor volume was calculated using the formula (width2 × length)/2.

Results

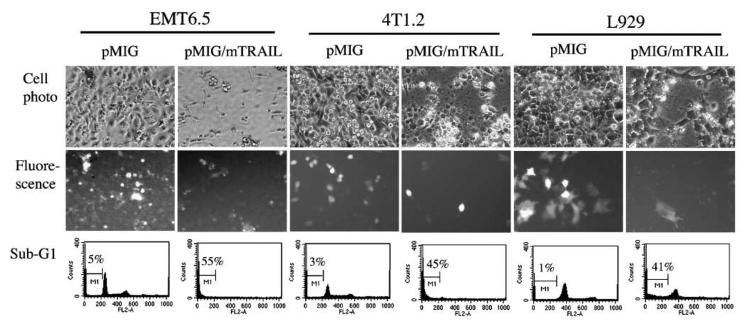

Bone marrow transduction and transplantation result in exogenous gene expression in vivo

Before our animal experiments, we tested the biological function of our TRAIL-expressing retroviral vector in vitro. Retroviral supernatant was generated from BOSC23 cells that were transduced with either pMIG vector control or pMIG-mTRAIL. These retroviral supernatants were tested by infecting mouse tumor EMT6.5, 4T1.2, and L929 cells. We confirmed retroviral-mediated gene transfer by analyzing the level of exogenous GFP expression in the transduced cells. On day 4 after transduction, cells transduced with mTRAIL-expressing retroviral supernatant showed characteristics of morphologic cell death, shown by GFP expression and cell morphology (Fig. 1), compared with control cells (Fig. 1). Apoptotic cells were also quantified by measuring the sub-G1 apoptotic cell population. As shown in Fig. 1, all the three mouse tumor cell lines that were transduced with TRAIL had 40% to 50% increases in the level of apoptosis compared with the control cells. These observations indicate that our TRAIL-expressing retroviral vector has the expected biological function. The retroviral supernatant was used in the subsequent in vivo gene transfer experiments.

Figure 1.

Infection of mouse tumor EMT6.5, 4T1.2, and L929 cells with pMIG/mTRAIL retrovirus leads to cell death. Top, EMT6.5, 4T1.2, and L929 cells on day 4 following infection either with pMIG (left) or pMIG/mTRAIL retrovirus (right); middle, GFP fluorescence; bottom, histogram of flow cytometry analysis for sub-G1 cell population with counts versus propidium iodide staining intensity.

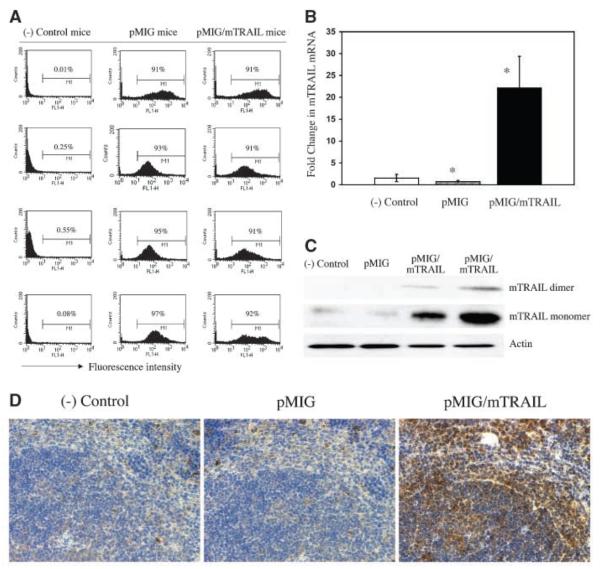

The in vivo gene transfer was done first through retroviral infection of primary bone marrow cells in culture, which were prepared from bone marrow donor mice. The GFP-positive bone marrow cells were sorted and then transplanted into lethally irradiated bone marrow recipient mice of the same strain. To evaluate the success of gene transfer in vivo, peripheral WBC samples were obtained from bone marrow–transplanted mice 4 weeks after bone marrow transplantation and tested for gene expression. GFP expression was determined in WBCs by flow cytometry. Control mice were transplanted with donor bone marrow cells that had not been infected with retrovirus, and their WBCs showed a GFP signal that did not differ from background (Fig. 2A, left column). WBCs from mice transduced with the control retrovirus (pMIG) showed a 90% or higher level of positive GFP (Fig. 2A, middle column). Similarly, the WBC population derived from TRAIL-transduced mice had >90% GFP-positive cells (Fig. 2A, right column). To further test whether GFP-expressing WBCs also express exogenous TRAIL, we detected mTRAIL mRNA levels by quantitative real-time PCR. We observed that TRAIL-transduced mice had a 22-fold increase in TRAIL mRNA compared with either control mice that received noninfected bone marrow cells or GFP-transduced mice (Fig. 2B). Western blot analysis also showed increased expression of TRAIL protein in WBC samples from TRAIL-transduced mice (Fig. 2C, columns 3 and 4, top two rows). The Western blot analysis revealed two forms of TRAIL in the range of 30 to 40 kDa. The higher form, migrating at ~40 kDa, represents the TRAIL dimer, whereas the faster moving 30-kDa form represents the TRAIL monomer. These data indicate that ~90% of hematopoietic cells in retroviral-transduced mice carried copies of the exogenous gene and that exogenous mTRAIL gene transfer through this approach led to increased TRAIL protein expression in hematopoietic cells in vivo. Furthermore, we detected increased level of mTRAIL protein in organ samples from mTRAILtransduced mice. As can be easily seen in Fig. 2D, spleen tissue from mTRAIL-transduced mice shows remarkably increased mTRAIL protein expression detected by immunohistochemistry staining with mTRAIL mAb. Taken together, all these observations confirm that mTRAIL gene transfer through bone marrow transduction and transplantation leads to mTRAIL protein overexpression in the bone marrow recipient mice.

Figure 2.

A, GFP expression detected by FACS of WBCs from bone marrow recipient mice. Results obtained 1 month after bone marrow transplantation comparable with those at 2 months (data not shown). Each value represents result from one mouse. Representative results. (−) Control mice received bone marrow without retroviral infection. pMIG mice received pMIG retroviral-infected bone marrow. pMIG/mTRAIL mice received bone marrow infected with the pMIG/mTRAIL retrovirus. B, level of mTRAIL mRNA transcription in vivo. Results obtained from samples of WBCs from groups of mice indicated in Fig. 2A 2 months after bone marrow transplantation. Columns, mean results from 12 mouse samples (n = 12 in each group). *, P < 0.01, ANOVA. C, mTRAIL protein expression in vivo detected by Western blotting. Result obtained from WBC samples from bone marrow recipient mice 1 month after bone marrow transplantation and detected by Western blotting with mTRAIL-specific antibody. Sample label is indicated in Fig. 2A. One mouse sample. D, mTRAIL protein overexpression in spleen tissue from mTRAIL-transduced mouse. Positive immunohistochemistry staining for mTRAIL in pMIG/mTRAIL sample. Result obtained from the same mice as indicated in Fig. 2C.

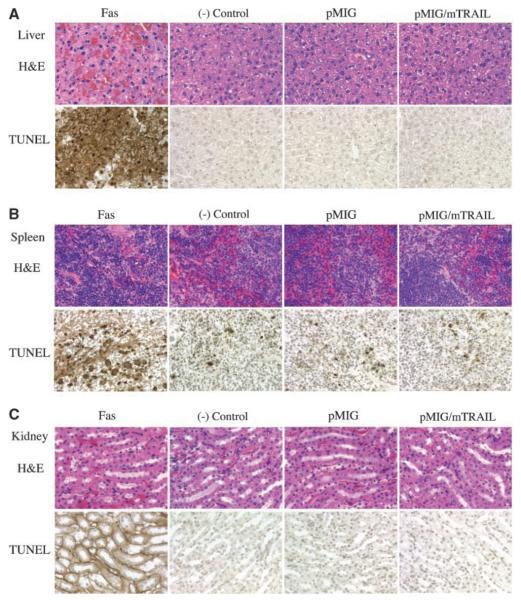

TRAIL overexpression was not toxic to normal cells in vivo

Although it has been shown that systemic delivery of a recombinant secreted form of the mTRAIL protein does not cause any detectable toxicity to normal tissues in vivo (10), it was not known whether overexpression of full-length mTRAIL in vivo would be toxic to normal tissues. As different recombinant formulations of soluble TRAIL may greatly affect the biological function of the protein (9, 10, 13, 28), we analyzed the potential in vivo toxic effect of full-length TRAIL. In these studies, physical evaluations of mice and histopathologic studies of tissue samples isolated from bone marrow recipient mice were carried out 1 and 2 months after bone marrow transplantation, by which time the reconstituted bone marrowhad replaced the original bone marrow function. TRAIL-transduced mice did not have abnormal body weight, body temperature, or heart rate. Neither did they evince abnormal activity compared with normal control mice (data not shown). The life span of TRAIL-transduced mice was in the reference range (they lived 1.5 years before being euthanized; n = 3). To determine whether the expression of the exogenous TRAIL gene in hematopoietic cells would affect cell numbers in peripheral blood populations, a complete blood count and a differential count were done using an automated hematology analyzer. We found that all RBC and WBC variables and indices were within the reference range for mice as shown in Table 1. To evaluate whether mTRAIL overexpression in vivo would be toxic to other organ tissues, we carried out histopathologic examination on various organ tissues from bone marrow recipient mice. Throughout our study, we did not find abnormal changes in various organ tissues that we examined from mTRAIL-transduced mice, and here, we show some examples. Liver tissue (Fig. 3A) from mTRAIL-transduced mice (pMIG/mTRAIL) was normal compared with tissues from mice that received noninfected bone marrow [(−) control] or bone marrow infected with control retrovirus (pMIG). As the positive control, samples (Fas) from mice that received 50 μg of Fas agonist antibody by i.v. injection showed hemorrhage in H&E staining and massive apoptosis in TUNEL staining (Fig. 3A). In spleen samples (Fig. 3B), mTRAIL-transduced mice samples stained for apoptosis were not appreciably different compared with samples obtained from (−) control and pMIG mice. Again, spleen sample from Fas agonist antibody-treated mouse showed broad apoptosis by TUNEL staining (Fig. 3B). In kidney (Fig. 3C), sample from Fas agonist antibody-treated mouse showed severe apoptosis in all kidney cells by TUNEL staining, but there was no observable toxicity in kidney samples from mTRAIL-transduced mice (Fig. 3C). Similar results were also observed in other organ samples, such as heart, lungs, and brain (data not shown). Similarly, Cr release assay on normal primary cells from mice (spleen, liver, kidney, cardiac muscle, and brain) did not show any TRAIL toxicity (Supplementary Fig. S1). Together, these results indicate that TRAIL overexpression is not toxic to normal cells in vivo.

Table 1.

Blood counts from bone marrow recipient mice

| RBCs | Hemoglobin | WBCs | Lymphocytes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reference range | 6.7-12.5 × 106/μL | 10.2-16.6 × g/dl | 5.4-16 × 103/μL | 55-95% |

| (−) Control (n = 4) | 9.6 ± 0.45 | 12.3 ± 0.36 | 9.35 ± 1.61 | 85.75 ± 3.95 |

| pMIG (n = 4) | 7.99 ± 0.73 | 10.46 ± 0.85 | 8.53 ± 0.82 | 68 ± 6.73 |

| pMIG/mTRAIL (n = 9) | 8.49 ± 0.66 | 11.07 ± 0.83 | 7.12 ± 1.95 | 66.44 ± 9.06 |

NOTE: Reference range for mouse blood counts of RBCs, hemoglobin, WBCs, and lymphocytes from Massachusetts Institute of Technology diagnostic laboratory reference data. (−) Control mice received bone marrow cells that had not been treated with retroviral infection. The other two groups of mice received bone marrow cells infected with either pMIG alone or with the pMIG/mTRAIL retrovirus. Results were obtained 1 month after bone marrowtra nsplantation. Results from 2 months after bone marrowtran splantation were comparable (data not shown).

Figure 3.

Histology and pathology examination on tissues from bone marrow recipient mice. A, top, left to right, liver samples from Fas, mice that received 50 μg Fas agonist antibody via i.v. injection. The samples were harvested and processed for pathology study 5 hours after the injection; (−) control, mice that received donor bone marrow that was not infected by retrovirus; pMIG, pMIG-transduced mice; pMIG/mTRAIL, pMIG/mTRAIL-transduced mice. Top, H&E staining; bottom, TUNEL staining. Liver hemorrhage can be seen in H&E staining of the Fas sample. B, spleen samples labeled in the same order as in Fig. 3A. C, kidney samples labeled in the same order as in Fig. 3A.

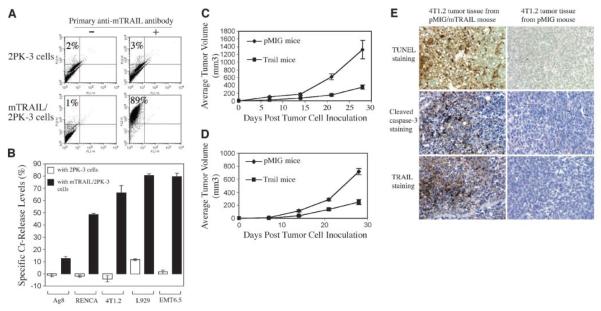

TRAIL gene transfer leads to inhibition of syngeneic tumor growth in vivo

To test whether exogenous mTRAIL gene expression in vivo could contribute to the inhibition of syngeneic tumor challenge to mice, we used the mouse mammary carcinoma cell lines EMT6.5 or 4T1.2 in a tumor challenge experiment in BALB/c mice. We first confirmed TRAIL sensitivity of these cell lines in a Cr release assay using mTRAIL/2PK-3 cells as effector cells. As shown in Fig. 4A, mTRAIL expression was detected in >80% of the cell population of mTRAIL/2PK-3 cells. We chose EMT6.5 and 4T1.2 cells for in vivo tumor study because those cells are among the most sensitive to mTRAIL in Cr release assay (Fig. 4B).

Figure 4.

A, mTRAIL protein expression on mTRAIL/2PK-3 cells. 2PK-3 cells and mTRAIL/2PK-3 cells were incubated with either nonimmune rat IgG (−) or N2B2 anti-mTRAIL (+) antibody followed by biotin-conjugated goat anti-rat Ig and phycoerythrin conjugate and analyzed by FACS channel 2 for phycoerythrin. mTRAIL/2PK-3 cells were used to select mTRAIL-sensitive mouse tumor cells. B, Cr release assay for selection of mTRAIL-sensitive mouse tumor cell lines. Columns, result from four replicate samples (n = 4). P < 0.01, for samples with 2PK-3 cells versus samples with mTRAIL/2PK-3 cells (Student's t test). Four experiments were done with consistently similar results. C, EMT6.5 tumor growth in bone marrow recipient mice. Points, mean from 9 mice in pMIG group (n = 9) and from 12 mice in pMIG/mTRAIL group (TRAIL mice; n = 12). P < 0.005, by day 28 (Student's t test). Experiment repeated thrice with similar results. D, 4T1.2 tumor growth in bone marrow recipient mice. Points, mean from 12 mice in each group (n = 12; labeled as the same in Fig. 4C). P < 0.005, by day 28 (Student's t test). E, inhibition of tumor growth in mTRAIL-transduced mice involves mTRAIL-induced apoptosis: evidence by immunohistochemistry staining. The tumor tissues were harvested by the 4th week after the tumor cell inoculation and immediately processed in TUNEL staining, cleaved caspase-3 staining, and mTRAIL staining. The tumor tissue from pMIG/mTRAIL-transduced mice shows intensive apoptosis by TUNEL staining, highly positive staining of cleaved caspase-3, and presence of high level of mTRAIL protein. Those positive staining results cannot be observed in the tumor tissues from pMIG-transduced mice.

One month after mTRAIL gene transfer through bone marrow transplantation, equal numbers of EMT6.5 tumor cells were inoculated by s.c. injection into two groups of BALB/c mice (1 × 105 per mouse), a control group that received null retroviral-infected bone marrow cells and a TRAIL group that received bone marrow cells infected with mTRAIL gene-expressing retrovirus. Tumor growth was monitored by measuring tumor volume at the injection site. As shown in Fig. 4C, tumors still grew in the TRAIL group of mice, but the average tumor volumes in the TRAIL group were smaller than those of the control group at equivalent time points. By 4 weeks after tumor inoculation, average tumor volume in the TRAIL group was 3-fold smaller than that in the control group, indicating that tumor growth in the TRAIL group was significantly retarded compared with the control group. In a separate experiment, we assessed the primary growth of 4T1.2 mouse mammary carcinoma cells injected into the mammary fat pad of a group of control and a group of the TRAIL-transduced mice (2.5 × 104 per mouse). Similar to our observations with the EMT6.5 tumor cells, 4T1.2 tumors also grew in almost all of the TRAIL mice (one mouse failed to develop tumors for 3 weeks), but the growth rate in the TRAIL mice was significantly retarded (Fig. 4D). By 4 weeks, the average volume of the primary tumors in the TRAIL mice was 2.8-fold smaller than those in control mice. These results show that the full-length coding sequence of mTRAIL gene, transferred into hematopoietic cells in mice by bone marrow transplantation, can confer increased tumor inhibition on the host.

To further examine whether the tumor inhibition in vivo involved TRAIL-induced apoptosis, we collected 4T1.2 tumor tissue samples from the pMIG and TRAIL mice and did immunohistochemistry staining for evidence of tumor apoptosis and TRAIL expression in tumor tissue. We observed strong evidence of increased apoptosis in 4T1.2 tumor tissue from TRAIL mice by TUNEL and cleaved caspase-3 staining (Fig. 4E), and the increased apoptosis was accompanied by positive staining of TRAIL protein in the tumor tissue (Fig. 4E), which were not observed in 4T1.2 tumor tissue from the pMIG group. The result suggests that TRAIL-induced apoptosis contributes to tumor inhibition in mTRAIL-transduced mice.

Discussion

TRAIL is a type II membrane protein (extracellular COOH terminal) of 281 amino acids (5, 6). Like TNF, TRAIL can also be cleaved from the cell membrane by metalloproteinases to yield a soluble, biologically active form (29). Structural studies have shown that biologically active soluble TRAIL is a homotrimer with the cysteine residues at position 230 coordinating a zinc ion. These cysteine residues and zinc ion are essential for the proper folding, trimer association, and biological activity of TRAIL (30).

Discovery of the differential tumoricidal capabilities of TRAIL has made it a promising candidate for the development of anticancer therapies. In this regard, recombinant soluble forms of human and mTRAIL protein have been tested for antitumor activity and toxicity to normal tissue cells. This includes a soluble form of human or murine TRAIL fused to a trimerizing leucine zipper (10), a nontagged soluble form of human TRAIL (9) and a polyhistidine-tagged soluble form of human TRAIL (13). The recombinant formulation seems important because a histidine-tagged human TRAIL was implicated in toxicity to human hepatocytes in vitro (13), whereas a nontagged human TRAIL was found nontoxic to human or cynomolgus monkey hepatocytes (28). This suggests that different recombinant formulations of soluble TRAIL may greatly affect the biological function of the protein.

The in vivo antitumor function of recombinant TRAIL protein was first shown in xenograft animal models, in which soluble human TRAIL protein was given to immunodeficient mice bearing human tumor cells (9, 10). Those studies showed the efficacy with which the protein inhibited growth of the xenograft tumor and evinced no toxicity of the recombinant TRAIL in animals. Although human and murine forms of TRAIL protein share 65% amino acid identity and a certain range of cross-reactivity to human and murine target cells (5), the cross-reactivity is not identical between the two species. For example, a leucine zipper form of human TRAIL was 300% more active than its murine counterpart in a human Jurkat cell line (5, 10). Therefore, a xenogeneic system might not be able to provide the ultimate answer to the issue of potential toxicity of TRAIL. A syngeneic system, by contrast, can provide a physiologic condition in which to test the potential toxicity of TRAIL protein to normal tissue cells in vivo.

Although TRAIL mRNA was found in a broad range of tissues and cells in the body (5), TRAIL protein has mainly been detected in immune cell types, such as CD4+, CD8+, NK cells, B cells, macrophages, monocytes, and dendritic cells. However, among those cell types, only murine NK cells constitutively express TRAIL, whereas the other human and murine cell types express TRAIL following activation (14, 31). TRAIL function in innate immunosurveillance by NK cells against tumor development was shown in TRAIL gene knockout mice (3). In those mice, the cytotoxicity of liver, but not spleen, NK cells was reduced, whereas liver metastasis, growth of syngeneic tumor grafts in the mammary fat pad, and fibrosarcoma induction by methylcholanthrene were all increased in the absence of TRAIL expression. In other studies, functional TRAIL expression was also found in some organ tissues, such as the eye, an immune-privileged site. Human and mouse ocular tissue cells constitutively express TRAIL, and tumor surveillance by TRAIL in the eye was shown in experimental mice (32). An important role for TRAIL in T-cell–mediated graft-versus-tumor activity has also been shown in mice (4). Although the importance of TRAIL in immunosurveillance has been documented in several experimental animal models, the functional significance of TRAIL expression to various organs is not fully understood.

To determine whether overexpression of full-length TRAIL would have tumor selectivity in a syngeneic mouse system, we generated mice that overexpress the mouse full-length coding sequence of the TRAIL gene in their bone marrowcells by retrovirus-mediated gene transfer into donor bone marrow cells followed by bone marrow transplantation into recipient mice. We asked whether full-length TRAIL can be overexpressed in hematopoietic cells and whether overexpression of TRAIL in vivo would enhance antitumor surveillance while remaining nontoxic to normal tissue cells. This approach has several advantages in that the major cell population overexpressing TRAIL would be hematopoietic cells, including immune cells and other leukocytes, which are the major cellular force in antitumor activity in the body. The effect of TRAIL overexpression by those cells is clinically relevant; it is a syngeneic system in which the potential toxicity of mTRAIL to tissues of same genetic background is evaluated. Thus, the model can be a useful tool for study of TRAIL biological function in vivo. Our data provide clear evidence for an antitumor function of TRAIL overexpression in vivo; furthermore, TRAIL overexpression was not toxic to normal tissues of TRAIL-transduced mice. Our assessment of the safety of full-length TRAIL is consistent with the results from the previous study by Walczak et al. (10) using soluble TRAIL protein. A study of graft-versus-tumor response after allogeneic hematopoietic cell and tumor cell transplantation in mice also found that TRAIL expression by alloreactive T cells is required for optimal graft-versus-tumor activity, whereas the TRAIL expression is not toxic to normal tissues in the host because TRAIL is not involved in alloreactive T-cell–mediated graft-versus-host disease (4). Again, our result correlates well with this finding and complements new evidence that, in the syngeneic system, TRAIL overexpression in vivo does not cause toxicity to normal tissues.

Although tumor inhibition was clearly seen in TRAIL-transduced mice inoculated with either EMT6.5 or 4T1.2 tumors, these animals still died of their tumors eventually (survival data not complete due to euthanasia of moribund mice with large tumors). This suggests that TRAIL could only partially inhibit tumor growth in those experimental mice. Combining TRAIL with another antitumor agent as a multiple antitumor approach may be more effective than activation of the TRAIL pathway alone; for example, increasing TRAIL expression combined with inhibition of angiogenesis might be a more effective approach to tumor inhibition.

One important question remaining to be elucidated about TRAIL is how its tumor selectivity is achieved. Some intracellular proteins are thought to be key regulators of TRAIL-induced apoptosis. For example, overexpression of Bcl-2 or Bcl-XL in several human cancer cell lines blocks TRAIL-induced cell death (33-36). TRAIL sensitivity is also associated with cellular FLICE inhibitory protein expression in several human cell lines (37-40). Nuclear factor-κB, Akt, and the FOXO family of forkhead transcription factors are also implicated in the regulation of TRAIL sensitivity of some cancer cells (27, 41-44). Regulation of TRAIL-induced apoptosis by those proteins seems to be cell type-dependent because studies on some other cell types failed to show a similar effect (45-48). Most of those studies were done in vitro, and it will also be necessary to determine whether those regulators have same functions in vivo. In this regard, our animal model may be explored further as a valuable tool for studying the function of potential regulator protein in TRAIL-induced inhibition on tumor growth by testing different types of cancer cells in vivo. This model may also be used to assess the efficacy of combining TRAIL with other therapeutic agents on tumor inhibition in vivo.

In summary, we studied TRAIL function in vivo through the overexpression of the full-length mTRAIL gene coding sequence in hematopoietic cells in mice. Our results are the first to show that TRAIL overexpression in hematopoietic cells can confer inhibition of the growth of syngeneic tumor grafts and that TRAIL overexpression is not toxic to normal tissues. Our future goal is to study how tumor selectivity of TRAIL is regulated and how to improve the tumoricidal activity of TRAIL with other antitumor agents in vivo.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Grant support: NIH grants CA105306 and HL080192 (R. Khosravi-Far), CA81421 (R.L. Anderson), and 5 T32 HL07893 (N. Benhaga). R. Khosravi-Far is a scholar of American Cancer Society. Immunohistochemical methodology was supported by the Specialized Histopathology Core Laboratory of the Dana-Farber/Harvard Cancer Center (NIH grant P30CA6516).

Footnotes

Note: Supplementary data for this article are available at Cancer Research Online (http://cancerres.aacrjournals.org/).

Unpublished observation.

References

- 1.Russell JH, Ley TJ. Lymphocyte-mediated cytotoxicity. Annu Rev Immunol. 2002;20:323–70. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.20.100201.131730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lieberman J. Mechanisms of granule-mediated cytotoxicity. Curr Opin Immunol. 2003;15:513–5. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cretney E, Takeda K, Yagita H, Glaccum M, Peschon JJ, Smyth MJ. Increased susceptibility to tumor initiation and metastasis in TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand-deficient mice. J Immunol. 2002;168:1356–61. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.3.1356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schmaltz C, Alpdogan O, Kappel BJ, et al. T cells require TRAIL for optimal graft-versus-tumor activity. Nat Med. 2002;8:1433–7. doi: 10.1038/nm1202-797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wiley SR, Schooley K, Smolak PJ, et al. Identification and characterization of a new member of the TNF family that induces apoptosis. Immunity. 1995;3:673–82. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(95)90057-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pitti RM, Marsters SA, Ruppert S, Donahue CJ, Moore A, Ashkenazi A. Induction of apoptosis by Apo-2 ligand, a new member of the tumor necrosis factor cytokine family. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:12687–90. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.22.12687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ogasawara J, Watanabe-Fukunaga R, Adachi M, et al. Lethal effect of the anti-Fas antibody in mice. Nature. 1993;364:806–9. doi: 10.1038/364806a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nagata S. Apoptosis by death factor. Cell. 1997;88:355–65. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81874-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ashkenazi A, Pai RC, Fong S, et al. Safety and antitumor activity of recombinant soluble Apo2 ligand. J Clin Invest. 1999;104:155–62. doi: 10.1172/JCI6926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Walczak H, Miller RE, Ariail K, et al. Tumoricidal activity of tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand in vivo. Nat Med. 1999;5:157–63. doi: 10.1038/5517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Motoki K, Mori E, Matsumoto A, et al. Enhanced apoptosis and tumor regression induced by a direct agonist antibody to tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand receptor 2. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:3126–35. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-1867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pukac L, Kanakaraj P, Humphreys R, et al. HGS-ETR1, a fully human TRAIL-receptor 1 monoclonal antibody, induces cell death in multiple tumour types in vitro and in vivo. Br J Cancer. 2005;92:1430–41. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jo M, Kim TH, Seol DW, et al. Apoptosis induced in normal human hepatocytes by tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand. Nat Med. 2000;6:564–7. doi: 10.1038/75045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kayagaki N, Yamaguchi N, Nakayama M, Eto H, Okumura K, Yagita H. Type I interferons (IFNs) regulate tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL) expression on human T cells: a novel mechanism for the antitumor effects of type I IFNs. J Exp Med. 1999;189:1451–60. doi: 10.1084/jem.189.9.1451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mackay F, Kalled SL. TNF ligands and receptors in autoimmunity: an update. Curr Opin Immunol. 2002;14:783–90. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(02)00407-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mariani SM, Krammer PH. Surface expression of TRAIL/Apo-2 ligand in activated mouse T and B cells. Eur J Immunol. 1998;28:1492–8. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199805)28:05<1492::AID-IMMU1492>3.0.CO;2-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Martinez-Lorenzo MJ, Alava MA, Gamen S, et al. Involvement of APO2 ligand/TRAIL in activation-induced death of Jurkat and human peripheral blood T cells. Eur J Immunol. 1998;28:2714–25. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199809)28:09<2714::AID-IMMU2714>3.0.CO;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang S, El-Deiry WS. TRAIL and apoptosis induction by TNF-family death receptors. Oncogene. 2003;22:8628–33. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zamai L, Ahmad M, Bennett IM, Azzoni L, Alnemri ES, Perussia B. Natural killer (NK) cell-mediated cytotoxicity: differential use of TRAIL and Fas ligand by immature and mature primary human NK cells. J Exp Med. 1998;188:2375–80. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.12.2375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Takeda K, Hayakawa Y, Smyth MJ, et al. Involvement of tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand in surveillance of tumor metastasis by liver natural killer cells. Nat Med. 2001;7:94–100. doi: 10.1038/83416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kayagaki N, Yamaguchi N, Nakayama M, et al. Expression and function of TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand on murine activated NK cells. J Immunol. 1999;163:1906–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rockwell S. In vivo-in vitro tumor systems: new models for studying the response of tumor to therapy. Lab Anim Sci. 1977;27:831–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lelekakis M, Moseley JM, Martin TJ, et al. A novel orthotopic model of breast cancer metastasis to bone. Clin Exp Metastasis. 1999;17:163–70. doi: 10.1023/a:1006689719505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jin TG, Kurakin A, Benhaga N, et al. Fas-associated protein with death domain (FADD)-independent recruitment of c-FLIPL to death receptor 5. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:55594–601. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M401056200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yang X, Khosravi-Far R, Chang HY, Baltimore D. Daxx, a novel Fas-binding protein that activates JNK and apoptosis. Cell. 1997;89:1067–76. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80294-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Song K, Chang Y, Prud'homme GJ. Regulation of T-helper-1 versus T-helper-2 activity and enhancement of tumor immunity by combined DNA-based vaccination and nonviral cytokine gene transfer. Gene Ther. 2000;7:481–92. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3301123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ghaffari S, Jagani Z, Kitidis C, Lodish HF, Khosravi-Far R. Cytokines and BCR-ABL mediate suppression of TRAIL-induced apoptosis through inhibition of fork-head FOXO3a transcription factor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:6523–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0731871100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lawrence D, Shahrokh Z, Marsters S, et al. Differential hepatocyte toxicity of recombinant Apo2L/TRAIL versions. Nat Med. 2001;7:383–5. doi: 10.1038/86397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schneider P, Tschopp J. Apoptosis induced by death receptors. Pharm Acta Helv. 2000;74:281–6. doi: 10.1016/s0031-6865(99)00038-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bodmer JL, Meier P, Tschopp J, Schneider P. Cysteine 230 is essential for the structure and activity of the cytotoxic ligand TRAIL. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:20632–7. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M909721199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Smyth MJ, Takeda K, Hayakawa Y, Peschon JJ, van den Brink MR, Yagita H. Nature's TRAIL—on a path to cancer immunotherapy. Immunity. 2003;18:1–6. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(02)00502-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lee HO, Herndon JM, Barreiro R, Griffith TS, Ferguson TA. TRAIL: a mechanism of tumor surveillance in an immune privileged site. J Immunol. 2002;169:4739–44. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.9.4739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Munshi A, Pappas G, Honda T, et al. TRAIL (APO-2L) induces apoptosis in human prostate cancer cells that is inhibitable by Bcl-2. Oncogene. 2001;20:3757–65. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fulda S, Meyer E, Debatin KM. Inhibition of TRAIL-induced apoptosis by Bcl-2 overexpression. Oncogene. 2002;21:2283–94. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Guo BC, Xu YH. Bcl-2 over-expression and activation of protein kinase C suppress the trail-induced apoptosis in Jurkat T cells. Cell Res. 2001;11:101–6. doi: 10.1038/sj.cr.7290074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lamothe B, Aggarwal BB. Ectopic expression of Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL inhibits apoptosis induced by TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL) through suppression of caspases-8, 7, and 3 and BID cleavage in human acute myelogenous leukemia cell line HL-60. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 2002;22:269–79. doi: 10.1089/107999002753536248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Griffith TS, Chin WA, Jackson GC, Lynch DH, Kubin MZ. Intracellular regulation of TRAIL-induced apoptosis in human melanoma cells. J Immunol. 1998;161:2833–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kim K, Fisher MJ, Xu SQ, el-Deiry WS. Molecular determinants of response to TRAIL in killing of normal and cancer cells. Clin Cancer Res. 2000;6:335–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kim Y, Suh N, Sporn M, Reed JC. An inducible pathway for degradation of FLIP protein sensitizes tumor cells to TRAIL-induced apoptosis. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:22320–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M202458200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhang X, Jin TG, Yang H, DeWolf WC, Khosravi-Far R, Olumi AF. Persistent c-FLIP(L) expression is necessary and sufficient to maintain resistance to tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand-mediated apoptosis in prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 2004;64:7086–91. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-1498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Thakkar H, Chen X, Tyan F, et al. Pro-survival function of Akt/protein kinase B in prostate cancer cells. Relationship with TRAIL resistance. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:38361–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M103321200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nesterov A, Lu X, Johnson M, Miller GJ, Ivashchenko Y, Kraft AS. Elevated AKT activity protects the prostate cancer cell line LNCaP from TRAIL-induced apoptosis. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:10767–74. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M005196200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ravi R, Bedi A. Requirement of BAX for TRAIL/Apo2L-induced apoptosis of colorectal cancers: synergism with sulindac-mediated inhibition of Bcl-x(L) Cancer Res. 2002;62:1583–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Modur V, Nagarajan R, Evers BM, Milbrandt J. FOXO proteins regulate tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis inducing ligand expression. Implications for PTEN mutation in prostate cancer. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:47928–37. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M207509200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Keogh SA, Walczak H, Bouchier-Hayes L, Martin SJ. Failure of Bcl-2 to block cytochrome c redistribution during TRAIL-induced apoptosis. FEBS Lett. 2000;471:93–8. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(00)01375-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhang XD, Zhang XY, Gray CP, Nguyen T, Hersey P. Tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand-induced apoptosis of human melanoma is regulated by smac/DIABLO release from mitochondria. Cancer Res. 2001;61:7339–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mitsiades N, Mitsiades CS, Poulaki V, Anderson KC, Treon SP. Intracellular regulation of tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand-induced apoptosis in human multiple myeloma cells. Blood. 2002;99:2162–71. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.6.2162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.LeBlanc HN, Ashkenazi A. Apo2L/TRAIL and its death and decoy receptors. Cell Death Differ. 2003;10:66–75. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.