Abstract

Insertion sequences (ISs) are mobile genetic elements in bacterial genomes. In general, intergenic IS elements are probably less deleterious for their hosts than intragenic ISs, simply because they have a lower likelihood of disrupting native genes. However, since promoters, Shine–Dalgarno sequences, and transcription factor binding sites are intergenic and upstream of genes, I hypothesized that not all neighboring gene orientations (NGOs) are selectively equivalent for IS insertion. To test this, I analyzed the NGOs of all intergenic ISs in 326 fully sequenced bacterial chromosomes. Of the 116 genomes with enough IS elements for statistical analysis, 68 have significantly more ISs between convergently oriented genes than expected, and 46 have significantly fewer ISs between divergently oriented genes. This suggests that natural selection molds intergenic IS distributions because they are least intrusive between convergent gene pairs and most intrusive between divergent gene pairs.

Keywords: insertion sequence, IS element, natural selection

Are All Intergenic Regions Created Equally?

Insertion sequences (ISs) are common transposable elements in bacterial genomes. Although IS elements can generate beneficial mutations (Cooper et al. 2001; Safi et al. 2004), they are generally considered genomic parasites because they only code for the enzyme required for their own transposition (Doolittle and Sapienza 1980; Orgel and Crick 1980). While an IS element inhabits a chromosomal location, it is inherited along with its host’s native genes, so its fitness is intimately tied to that of its host. Therefore, an IS that causes a deleterious mutation by disrupting an essential gene will probably be quickly eliminated from most natural populations, whereas an IS that inserts into a selectively neutral location will have a much greater chance of long-term survival (Lynch 2006). As a general rule, intergenic IS elements probably enjoy higher survival than those that integrate within genes, simply because they have a lower likelihood of disrupting native genes (Campbell 2002; Zaghloul et al. 2007). However, the question then arises: are all intergenic regions selectively equivalent for IS occupancy?

Bacterial genes can be transcribed from either the top (→) or bottom (←) DNA strand. Therefore, neighboring genes on bacterial chromosomes can occur in three possible orientations: tandem (→→ and ←←), convergent (→←), and divergent (←→). Because promoters, Shine–Dalgarno sequences, and transcription factor binding sites are upstream of genes, I hypothesized that the intergenic regions of the three neighboring gene orientations (NGOs) may not be selectively equivalent for IS insertion. Specifically, the intergenic region between: 1) ←→ neighbors will contain a promoter and a Shine–Dalgarno sequence for both genes, and possibly a transcription factor binding site for both, 2) →→ and ←← neighbors will contain a promoter (if the neighbors are not in the same operon) and a Shine–Dalgarno sequence for the respective downstream gene only, and possibly a transcription factor binding site for that gene, and 3) →← neighbors will contain no promoters, Shine–Dalgarno sequences, or transcription factor binding sites. Therefore, an IS that inserts between ←→ genes has a relatively high likelihood of disrupting the transcription or translation of its neighbors, an IS that inserts between →→ or ←← genes has a moderate likelihood of disrupting its neighbors, and an IS that inserts between →← genes will never disrupt its neighbors. Because of this discrepancy among intergenic regions, I hypothesized that intergenic ISs would be most common between →← oriented genes and least common between ←→ oriented genes in bacterial genomes.

Intergenic IS Elements Are Not Randomly Distributed

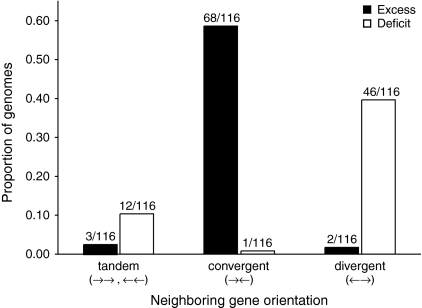

I tested this hypothesis by analyzing the NGOs of all intergenic ISs from 326 fully sequenced bacterial chromosomes. Of these, 116 genomes have enough ISs to meet χ2 test assumptions (Cochran 1954). Remarkably, 64% of these genomes (N = 74) have observed intergenic IS quantities that deviate significantly (P ≤ 0.05) from expectations (under the null assumptions of random insertion and no natural selection) (table 1). These deviations are pervasive across the phylogenetic spectrum of Bacteria (table 1) and include a wide variety of IS families. Two NGOs exhibit extraordinary consistency in their contributions to these deviations: →← harbors significant IS excesses in 68 genomes and one significant deficit, and ←→ harbors two significant IS excesses and 46 significant deficits (fig. 1 and table 1). Overall, 105 of the 116 analyzed genomes contain more IS elements in the →← orientation than expected, and 104 contain fewer in the ←→ orientation than expected (the binomial probabilities of having distributions at least this skewed just by chance are 1.1 × 10−20 and 9.3 × 10−20, respectively) (table 1). These nonrandom IS distributions also extend to bacterial chromosomes that contain relatively few IS elements. Specifically, of the 131 genomes that do not contain enough ISs for statistical analysis (Cochran 1954) but that have ≥1 expected IS in each NGO, 117 genomes contain more IS elements in the →← orientation than expected, and 108 contain fewer in the ←→ orientation than expected (the binomial probabilities of having distributions at least this skewed just by chance are 1.0 × 10−21 and 1.1 × 10−14, respectively) (supplementary table S1, Supplementary Material online).

Table 1.

Observed (O) and Expected (E) Quantities of Intergenic IS Elements in Fully Sequenced Bacterial Chromosomes, and the χ2 Test Statistic for Each

| NGOa |

|||||||

| →→ , ←← |

→← |

←→ |

|||||

| O | E | O | E | O | E | χ2b | |

| Actinobacteria | |||||||

| Corynebacterium efficiens YS-314 | 36 | 39.8 | 21 | 14.5 | 16 | 18.6 | 3.6 |

| Corynebacterium glutamicum ATCC 13032 | 21 | 20.5 | 11 | 7.4 | 7 | 11.1 | 3.3 |

| Corynebacterium jeikeium K411 | 38 | 38.1 | 18 | 8.5 | 12 | 21.5 | 14.9*** |

| Frankia sp. CcI3 | 88 | 79.1 | 27 | 16.6 | 21 | 40.4 | 16.9***c |

| Mycobacterium avium paratuberculosis | 29 | 33.8 | 14 | 7.6 | 14 | 15.6 | 6.3* |

| Mycobacterium bovis AF2122/97 | 22 | 22.7 | 15 | 6.6 | 6 | 13.7 | 15.1*** |

| Mycobacterium smegmatis MC2 | 33 | 37.9 | 24 | 7.1 | 11 | 23.0 | 47.3***c |

| Mycobacterium tuberculosis CDC1551 | 29 | 26.6 | 13 | 6.7 | 6 | 14.7 | 11.3** |

| M. tuberculosis H37Rv | 31 | 27.9 | 16 | 8.1 | 6 | 17.0 | 15.2*** |

| Streptomyces avermitilis MA-4680 | 36 | 38.1 | 25 | 11.6 | 8 | 19.3 | 22.3***c |

| Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2) | 19 | 20.6 | 9 | 6.1 | 11 | 12.3 | 1.7 |

| Bacteriodetes | |||||||

| Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron VPI-5482 | 22 | 30.9 | 24 | 7.2 | 6 | 13.8 | 45.7***c |

| Porphyromonas gingivalis W83 | 21 | 27.3 | 10 | 8.7 | 13 | 8.0 | 4.7 |

| Prevotella intermedia 17 | 26 | 27.1 | 14 | 10.1 | 9 | 11.8 | 2.3 |

| Salinibacter ruber DSM 13855 | 24 | 23.8 | 4 | 5.6 | 11 | 9.6 | 0.6 |

| Chlamydiae | |||||||

| Protochlamydia amoebophila UWE25 | 26 | 32.3 | 14 | 8.0 | 17 | 16.7 | 5.7 |

| Cyanobacteria | |||||||

| Anabaena variabilis ATCC 29413 | 35 | 31.5 | 16 | 8.1 | 7 | 18.4 | 15.0*** |

| Gloeobacter violaceus PCC7421 | 41 | 35.0 | 18 | 10.1 | 6 | 19.9 | 17.0***c |

| Nostoc sp. PCC 7120 | 39 | 37.1 | 17 | 8.7 | 11 | 21.1 | 12.8** |

| Synechococcus sp. JA-2-3Ba(2-13) | 42 | 37.6 | 21 | 27.7 | 16 | 13.7 | 2.5 |

| Synechococcus sp. JA-3-3Ab | 44 | 40.4 | 17 | 29.9 | 21 | 11.7 | 13.2*** |

| Synechocystis sp. PCC6803 | 30 | 30.4 | 17 | 6.9 | 5 | 14.7 | 21.0***c |

| Thermosynechococcus elongatus BP-1 | 41 | 30.5 | 6 | 6.6 | 17 | 26.9 | 7.3* |

| Deinococcus | |||||||

| Deinococcus radiodurans R1 | 17 | 18.1 | 10 | 6.0 | 4 | 7.0 | 4.1 |

| Firmicutes | |||||||

| Bacillus anthracis A0039 | 28 | 26.1 | 8 | 5.2 | 6 | 10.7 | 3.7 |

| B. anthracis Ames | 26 | 23.1 | 6 | 5.1 | 6 | 9.8 | 2.0 |

| B. anthracis Ames Ancestor | 26 | 24.3 | 7 | 5.4 | 7 | 10.3 | 1.7 |

| B. anthracis CNEVA-9066 | 27 | 24.4 | 7 | 5.1 | 6 | 10.4 | 2.8 |

| B. anthracis USA6153 | 27 | 25.3 | 8 | 5.2 | 6 | 10.5 | 3.6 |

| B. anthracis Vollum | 27 | 24.4 | 7 | 5.2 | 6 | 10.4 | 2.8 |

| Bacillus cereus 10987 | 37 | 32.3 | 6 | 6.6 | 8 | 12.2 | 2.2 |

| B. cereus ATCC 14579 | 27 | 28.6 | 9 | 5.0 | 9 | 11.4 | 3.8 |

| B. cereus Zk | 29 | 25.6 | 8 | 5.0 | 5 | 11.4 | 5.8 |

| Bacillus halodurans C-125 | 73 | 74.0 | 22 | 13.0 | 14 | 22.0 | 9.1** |

| Bacillus thuringiensis konkukian | 39 | 38.6 | 16 | 7.7 | 8 | 16.6 | 13.4*** |

| Clostridium perfringens SM101 | 39 | 39.9 | 9 | 7.7 | 12 | 12.4 | 0.2 |

| Desulfitobacterium hafniense Y51 | 66 | 60.9 | 6 | 11.3 | 18 | 17.8 | 2.9 |

| Geobacillus kaustophilus HTA426 | 65 | 51.4 | 10 | 13.7 | 8 | 17.9 | 10.1** |

| Staphylococcus epidermidis ATCC 12228 | 24 | 34.8 | 30 | 9.1 | 2 | 12.2 | 60.3***c |

| S. epidermidis RP62A | 24 | 31.7 | 23 | 9.6 | 5 | 10.7 | 23.6***c |

| Staphylococcus haemolyticus JCSC1435 | 36 | 57.0 | 44 | 10.6 | 5 | 17.4 | 121.4***c |

| Streptococcus pneumoniae G54 | 39 | 40.2 | 11 | 8.3 | 8 | 9.6 | 1.2 |

| S. pneumoniae R6 | 30 | 39.0 | 15 | 7.2 | 9 | 7.8 | 10.7** |

| S. pneumoniae TIGR4 | 37 | 43.7 | 22 | 11.7 | 6 | 9.7 | 11.6** |

| Thermoanaerobacter tengcongensis MB4(T) | 39 | 37.5 | 7 | 5.8 | 7 | 9.8 | 1.1 |

| Spirochaetes | |||||||

| Leptospira interrogans lai 56601 | 34 | 35.4 | 17 | 16.9 | 15 | 13.7 | 0.2 |

| Unclassified proteobacteria | |||||||

| Magnetococcus sp. MC-1 | 41 | 38.4 | 16 | 18.1 | 15 | 15.5 | 0.4 |

| Alphaproteobacteria | |||||||

| Bradyrhizobium japonicum USDA 110 | 58 | 65.3 | 31 | 21.7 | 28 | 30.0 | 5.0 |

| Caulobacter crescentus CB15 | 12 | 15.7 | 14 | 5.0 | 2 | 7.4 | 21.2***c |

| Gluconobacter oxydans 621H | 28 | 28.7 | 12 | 5.8 | 10 | 15.5 | 8.4* |

| Magnetospirillum magneticum AMB-1 | 33 | 24.0 | 9 | 8.6 | 4 | 13.4 | 9.9** |

| Mesorhizobium loti MAFF303099 | 31 | 29.9 | 13 | 7.1 | 11 | 17.9 | 7.6* |

| Nitrobacter winogradskyi Nb-255 | 50 | 51.4 | 34 | 13.8 | 11 | 29.7 | 41.2***c |

| Rhodopseudomonas palustris BisB18 | 15 | 23.4 | 19 | 7.7 | 8 | 10.9 | 20.7***c |

| Rickettsia bellii RML369-C | 24 | 24.0 | 6 | 6.5 | 10 | 9.5 | 0.1 |

| Sinorhizobium meliloti 1021 | 28 | 32.4 | 22 | 10.9 | 7 | 13.8 | 15.3*** |

| Wolbachia pipientis wMel | 23 | 24.7 | 15 | 6.6 | 3 | 9.7 | 15.4*** |

| Betaproteobacteria | |||||||

| Azoarcus sp. EbN1 | 63 | 61.4 | 29 | 16.8 | 11 | 24.8 | 16.7***c |

| Bordetella pertussis Tohama I | 68 | 79.9 | 52 | 13.1 | 15 | 42.0 | 134.2***c |

| Burkholderia cenocepacia AU 1054 | 30 | 40.5 | 23 | 9.3 | 18 | 21.2 | 23.3***c |

| Burkholderia mallei ATCC 23344 | 46 | 56.6 | 39 | 20.7 | 15 | 22.7 | 20.8***c |

| Burkholderia pseudomallei 1710b | 31 | 33.9 | 22 | 15.4 | 9 | 12.7 | 4.1 |

| B. pseudomallei K96243 | 26 | 29.8 | 22 | 10.2 | 6 | 13.9 | 18.6***c |

| Burkholderia thailandensis E264 | 40 | 38.8 | 21 | 13.6 | 9 | 17.6 | 8.2* |

| Burkholderia sp. 383 | 20 | 20.0 | 10 | 5.6 | 7 | 11.4 | 5.2 |

| Neisseria meningitidis MC58 | 21 | 29.3 | 21 | 10.2 | 8 | 10.5 | 14.2*** |

| N. meningitidis Z2491 | 14 | 22.3 | 17 | 8.1 | 8 | 8.6 | 12.8** |

| Nitrosomonas europaea ATCC 19718 | 37 | 52.6 | 30 | 9.7 | 19 | 23.7 | 48.4***c |

| Nitrosospira multiformis ATCC 25196 | 32 | 32.1 | 15 | 7.8 | 7 | 14.0 | 10.1** |

| Ralstonia solanacearum GMI1000 | 21 | 24.0 | 11 | 5.2 | 8 | 10.8 | 7.7* |

| Deltaproteobacteria | |||||||

| Desulfovibrio desulfuricans G20 | 33 | 28.7 | 12 | 10.8 | 5 | 10.5 | 3.6 |

| Geobacter metallireducens GS-15 | 48 | 50.0 | 16 | 8.9 | 14 | 19.0 | 7.0* |

| Myxococcus xanthus DK 1622 | 23 | 21.8 | 10 | 5.5 | 7 | 12.7 | 6.2* |

| Pelobacter carbinolicus DSM 2380 | 20 | 26.5 | 12 | 5.5 | 10 | 10.0 | 9.4** |

| Gammaproteobacteria | |||||||

| Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans ATCC 23270 | 33 | 34.4 | 14 | 8.0 | 8 | 12.6 | 6.3* |

| Coxiella burnetii RSA 493 | 17 | 16.9 | 3 | 5.0 | 10 | 8.1 | 1.2 |

| Escherichia coli CFT073 | 44 | 44.1 | 26 | 12.5 | 11 | 24.4 | 22.0***c |

| E. coli K12 MG1655 | 33 | 34.1 | 18 | 8.0 | 9 | 17.9 | 17.0***c |

| E. coli O157:H7 EDL933 | 24 | 28.6 | 16 | 5.7 | 6 | 11.7 | 22.3***c |

| E. coli O157:H7 VT2-Sakai | 38 | 44.1 | 26 | 9.0 | 8 | 18.9 | 39.0***c |

| E. coli UTI89 | 19 | 23.5 | 17 | 5.6 | 5 | 11.9 | 27.8***c |

| Francisella tularensis holarctica | 60 | 56.5 | 22 | 11.2 | 16 | 30.3 | 17.2***c |

| F. tularensis tularensis | 28 | 25.6 | 14 | 5.8 | 5 | 15.6 | 18.9***c |

| Hahella chejuensis KCTC 2396 | 25 | 22.0 | 5 | 5.4 | 8 | 10.6 | 1.1 |

| Legionella pneumophila Paris | 19 | 22.5 | 12 | 6.4 | 12 | 14.1 | 5.8 |

| Methylococcus capsulatus Bath | 16 | 17.2 | 10 | 5.7 | 6 | 9.1 | 4.3 |

| Nitrosococcus oceani ATCC 19707 | 48 | 52.3 | 17 | 11.5 | 23 | 24.2 | 3.0 |

| Photobacterium profundum SS9 | 121 | 109.1 | 38 | 30.3 | 35 | 54.6 | 10.3** |

| Photorhabdus luminescens TTO1 | 79 | 71.0 | 28 | 16.7 | 14 | 33.3 | 19.7***c |

| Pseudomonas putida KT2440 | 29 | 31.6 | 19 | 10.4 | 9 | 15.1 | 9.8** |

| Pseudomonas syringae DC3000 | 61 | 66.7 | 36 | 18.0 | 24 | 36.2 | 22.5***c |

| P. syringae pv B728a | 16 | 21.2 | 15 | 6.5 | 8 | 11.3 | 13.6*** |

| P. syringae pv phaseolicola | 58 | 57.6 | 28 | 16.7 | 19 | 30.7 | 12.1** |

| Psychrobacter arcticum 273-4 | 20 | 28.7 | 16 | 5.9 | 12 | 13.3 | 19.9***c |

| Salmonella enterica Choleraesuis | 18 | 28.4 | 19 | 7.7 | 13 | 13.9 | 20.4***c |

| Shewanella oneidensis MR-1 | 68 | 73.9 | 33 | 21.9 | 33 | 38.2 | 6.7* |

| Shigella boydii Sb227 | 100 | 114.6 | 55 | 24.0 | 48 | 64.4 | 46.1***c |

| Shigella dysenteriae Sd197 | 156 | 177.4 | 72 | 33.0 | 78 | 95.6 | 51.9***c |

| Shigella flexneri 2a 301 | 116 | 113.9 | 51 | 38.3 | 34 | 48.9 | 8.8* |

| S. flexneri 2a 2457T | 60 | 61.1 | 27 | 11.1 | 20 | 34.8 | 28.9***c |

| Shigella sonnei Ss046 | 103 | 100.8 | 37 | 23.1 | 36 | 52.1 | 13.3*** |

| Sodalis glossinidius morsitans | 12 | 18.3 | 7 | 6.8 | 14 | 7.9 | 6.9* |

| Vibrio cholerae El Tor N16961 | 15 | 12.7 | 6 | 5.0 | 3 | 6.3 | 2.3 |

| Vibrio vulnificus YJ016 | 24 | 25.2 | 15 | 6.9 | 6 | 13.0 | 13.4*** |

| Xanthomonas axonopodis pv. citri 306 | 28 | 28.2 | 11 | 8.9 | 8 | 9.9 | 0.9 |

| Xanthomonas campestris 8004 | 25 | 28.5 | 16 | 10.8 | 9 | 10.7 | 3.3 |

| X. campestris ATCC 33913 | 37 | 36.4 | 16 | 13.6 | 10 | 13.0 | 1.1 |

| X. campestris pv. armoraciae 756C | 24 | 22.6 | 14 | 12.5 | 4 | 6.9 | 1.5 |

| X. campestris pv. vesicatoria 85-10 | 33 | 34.4 | 12 | 11.5 | 14 | 13.1 | 0.1 |

| Xanthomonas oryzae KACC10331 | 179 | 189.6 | 93 | 77.2 | 44 | 49.2 | 4.3 |

| X. oryzae pv. oryzae MAFF 311018 | 155 | 170.2 | 91 | 58.5 | 45 | 62.3 | 24.2***c |

| X. oryzae pv. oryzicola BLS256 | 98 | 95.9 | 62 | 57.2 | 23 | 29.9 | 2.0 |

| Yersinia pestis biovar Medievalis 91001 | 37 | 38.4 | 29 | 10.3 | 2 | 19.3 | 49.3***c |

| Y. pestis CO92 | 44 | 48.7 | 35 | 13.0 | 7 | 24.3 | 50.0***c |

| Y. pestis KIM | 57 | 62.7 | 45 | 19.9 | 11 | 30.3 | 44.4***c |

| Yersinia pseudotuberculosis IP32593 | 17 | 19.4 | 12 | 5.0 | 5 | 9.6 | 12.3** |

NGOs in bold contribute a significant excess of observed ISs to significant χ2 deviations, and those in gray contribute a significant deficit of observed ISs.

Asterisks indicate significant P values: *P ≤ 0.05, **P ≤ 0.01, ***P ≤ 0.001.

P value is significant following a sequential Bonferroni (Rice 1989).

FIG. 1.—

Proportion of fully sequenced bacterial chromosomes with a significant excess or deficit of IS elements in each NGO. Each bar is labeled with the number of excesses or deficits relative to the number of genomes analyzed (i.e., the number of genomes with enough IS elements for statistical analysis; see text).

One possible explanation for these nonrandom IS distributions is a general insertion bias into →← and away from ←→ intergenic regions. I doubt that such a bias would result from target sequence specificity, largely because IS target site preferences are rarely very stringent or very long (Chandler and Mahillon 2002), so suitable insertion locations for many ISs occur thousands of times in each genome (Zaghloul et al. 2007). Instead, insertion bias could result from chromosomal differences between the three NGOs. For example, as bacterial genes are transcribed, DNA becomes positively supercoiled ahead of the polymerase and negatively supercoiled behind (Liu and Wang 1987). Consequently, the region between →← oriented genes may often be positively supercoiled, more so than between the other NGOs (and conversely, the region between ←→ genes may often be the most negatively supercoiled). If IS elements preferentially insert into positively supercoiled DNA, then this could explain the overabundances and underabundances of ISs between →← and ←→ oriented genes, respectively (fig. 1). However, no evidence exists for such an insertion bias, and some transposons prefer the opposite: negatively supercoiled DNA (Lodge and Berg 1990). Another possibility is that IS elements generally preferentially insert downstream of genes; for example, near transcription termination sequences. At least one IS element exhibits such a preference (Tetu and Holmes 2008), although this is not a ubiquitous tendency among ISs because some exhibit the opposite preference, inserting upstream of genes between Shine–Dalgarno sequences and start codons (Doran et al. 1997; Inglis et al. 2003). Therefore, insertion bias may affect the distribution of some IS elements in some bacterial genomes, although it is unlikely to explain the widespread bias exhibited across Bacteria (table 1).

Without any evidence for systematic IS insertion bias to explain these nonrandom IS distributions (table 1), the most likely explanation at present is that natural selection molds intergenic IS distributions. From a host bacterium’s perspective, all potential IS insertion locations are not equally viable, and natural selection eventually eliminates disadvantageous genotypes from most populations. In fact, few IS elements are probably truly selectively neutral because at the very least they appropriate host resources for transposase expression (Nuzhdin 1999). So unless a particular IS element beneficially impacts its host (Safi et al. 2004), the likely fate of most ISs is eventual extinction from their host population (Wagner 2006). For an individual IS locus, the likelihood of extinction is largely correlated to its fitness cost, with the most deleterious ISs eliminated most quickly, and those inserting in innocuous locations having the greatest potential for long-term survival (Lynch 2006). Therefore, the most innocuous ISs will be overrepresented in bacterial genomes, and the most deleterious will be underrepresented. The remarkable consistency with which intergenic IS elements are overrepresented and underrepresented between →← and ←→ oriented genes, respectively (fig. 1), suggests that these are generally relatively innocuous and deleterious insertion locations, thus supporting the hypothesis that differential selection pressure molds global intergenic IS distributions. Further fine-scale analyses of intergenic IS distributions (e.g., ISs may be less common between →→ and ←← neighbors when they are members of the same operon; ISs may be relatively rare next to highly expressed genes, no matter what their orientation) may shed additional light on the fate and impact of IS elements in bacterial genomes.

Materials and Methods

I obtained the primary annotations of all fully sequenced bacterial chromosomes from the Comprehensive Microbial Resource database (data releases 1.0–20.0) at The Institute for Genomic Research (http://cmr.tigr.org/tigr-scripts/CMR/CmrHomePage.cgi). Specifically, I obtained the locus name (i.e., the locus number), the common name, the nucleotide sequence, and the nucleotide positions of the 5' and 3' ends of all annotated proteins on each chromosome. My goal for each genome was to assess whether the observed quantities of intergenic IS elements located within each of the three NGOs differ from the quantities expected if insertion is random and not subsequently influenced by natural selection. This required four steps for each fully sequenced genome.

The first step was to find all chromosomal copies of intergenic IS elements. I used the BlastX program in the ISfinder database (http://www-is.biotoul.fr/is.html) (Siguier et al. 2006) to identify all coding sequences (CDSs) in each genome that exhibit homology to IS elements in the database. I considered a CDS with a best BlastX hit E value ≤10−10 to be an IS element (Touchon and Rocha 2007). Because I was only interested in the distribution of ISs between functional native bacterial genes, I took a relatively conservative approach when identifying intergenic IS elements (i.e., it is better to exclude some intergenic ISs than to include any intragenic ISs). Specifically, I eliminated the following IS elements from the analysis: 1) all intragenic ISs, including elements with at least one neighboring gene annotated as being truncated (or similar synonyms), conservatively assuming that the neighboring gene became degenerate following IS insertion into the gene; 2) all ISs bordered by genes with annotated frameshift or point mutations that introduce premature stop codons, conservatively assuming that these mutations preceded IS insertion; that is, the IS was never exposed to selection from two functional neighboring genes; 3) all ISs bordered by nonconsecutively numbered and therefore presumably nonneighboring genes (e.g., some are bordered by nonannotated gene remnants, which may have become degenerate following IS insertion); and 4) all ISs bordered by a phage-annotated gene, and those annotated as being or bordering an integron or an integrative genetic element (for the quantities of ISs eliminated for each of these reasons in each genome, see supplementary table S2, Supplementary Material online). Conversely, I included IS elements with both functional and nonfunctional transposases because ISs can affect their neighboring genes even if they are no longer mobile (e.g., by displacing promoters). Also, multiple IS insertions into the same intergenic space were included only once in the analysis.

The second step was to calculate the observed quantity of intergenic IS elements within each NGO (i.e., assessing whether the two neighboring genes are coded on the top or bottom DNA strand for each IS element). I did this by simply subtracting the nucleotide position of the 5' end from that of the 3' end for each neighbor, which produces a positive number for top strand genes and a negative number for bottom strand genes.

The third step was to calculate the expected quantity of intergenic IS elements within each NGO, assuming that IS insertion is random and not subsequently affected by natural selection. I calculated these expected quantities based on the premise that large and abundant NGO intergenic regions should receive more ISs than small and rare ones, all things being equal. Therefore, the expected quantities were calculated individually for each genome using the product of 1) the mean intergenic distance between neighboring native bacterial genes in the three NGOs and 2) the global proportion of each native gene pair NGO; for an example of this calculation, see table S3 (Supplementary Material online).

Finally, the fourth step was to use a χ2 goodness-of-fit test to assess whether the observed quantities of intergenic IS elements within each NGO deviate from the expected quantities. The assumptions of the χ2 test are that no cell has an expected value <1.0 and that ≤20% of cells have expected values <5.0 (Cochran 1954). Therefore, many fully sequenced genomes do not contain enough intergenic IS elements for statistical analysis (all 116 genomes with enough intergenic ISs are included in table 1, and the remaining 210 genomes are included in table S1, Supplementary Material online). I did not Bonferroni-adjust the χ2 test P values (Moran 2003), although all χ2 values that would be significant with a Bonferroni correction are indicated in table 1. To identify the NGOs contributing to each significant χ2 deviation, I performed cell-by-cell comparisons of observed and expected quantities using an adjusted residual method, considering any adjusted residual with an absolute value >2 to contribute significantly to the overall χ2 deviation (Agresti 1996).

Supplementary Material

Supplementary tables S1–S3 are available at Genome Biology and Evolution online (http://www.oxfordjournals.org/our_journals/gbe/).

Acknowledgments

I thank Huansheng Cao, Kevin Dougherty, Evelyn Fetridge, Catherine Ruggiero, Chad Thompson, and several anonymous reviewers for helpful comments on this manuscript, and Elizabeth Coffey for early contributions to this project. This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (grant number 1R15GM081862-01A1). This is contribution number 246 of the Louis Calder Center—Biological Field Station, Fordham University.

References

- Agresti A. An introduction to categorical data analysis. New York: John Wiley and Sons; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell A. Eubacterial genomes. In: Craig NL, Craigie R, Gellert M, Lambowitz A, editors. Mobile DNA II. Washington (DC): ASM Press; 2002. pp. 1024–1039. [Google Scholar]

- Chandler M, Mahillon J. Insertion sequences revisited. In: Craig NL, Craigie R, Gellert M, Lambowitz A, editors. Mobile DNA II. Washington (DC): ASM Press; 2002. pp. 305–366. [Google Scholar]

- Cochran WG. Some methods for strengthening the common χ2 test. Biometrics. 1954;10:417–451. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper VS, Schneider D, Blot M, Lenski RE. Mechanisms causing rapid and parallel losses of ribose catabolism in evolving populations of Escherichia coli B. J Bacteriol. 2001;183:2834–2841. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.9.2834-2841.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doolittle WF, Sapienza C. Selfish genes, the phenotype paradigm and genome evolution. Nature. 1980;284:601–603. doi: 10.1038/284601a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doran T, et al. IS900 targets translation initiation signals in Mycobacterium avium subsp. paratuberculosis to facilitate expression of its hed gene. Microbiology. 1997;143:547–552. doi: 10.1099/00221287-143-2-547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inglis NF, Stevenson K, Heaslip DG, Sharp JM. Characterisation of IS901 integration sites in the Mycobacterium avium genome. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2003;221:39–47. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1097(03)00136-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu LF, Wang JC. Supercoiling of the DNA template during transcription. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1987;84:7024–7027. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.20.7024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lodge JK, Berg DE. Mutations that affect Tn5 insertion into pBR322: importance of local DNA supercoiling. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:5956–5960. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.10.5956-5960.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch M. Streamlining and simplification of microbial genome architecture. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2006;60:327–349. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.60.080805.142300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moran MD. Arguments for rejecting the sequential Bonferroni in ecological studies. Oikos. 2003;100:403–405. [Google Scholar]

- Nuzhdin SV. Sure facts, speculations, and open questions about the evolution of transposable element copy number. Genetica. 1999;107:129–137. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orgel LE, Crick FHC. Selfish DNA: the ultimate parasite. Nature. 1980;284:604–607. doi: 10.1038/284604a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rice WR. Analyzing tables of statistical tests. Evolution. 1989;43:223–225. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.1989.tb04220.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Safi H, et al. IS6110 functions as a mobile, monocyte-activated promoter in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Mol Microbiol. 2004;52:999–1012. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04037.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siguier P, Perochon J, Lestrade L, Mahillon J, Chandler M. ISfinder: the reference centre for bacterial insertion sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:D32–D36. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkj014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tetu SG, Holmes AJ. A family of insertion sequences that impacts integrons by specific targeting of gene cassette recombination sites, the IS1111-attC group. J Bacteriol. 2008;190:4959–4970. doi: 10.1128/JB.00229-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Touchon M, Rocha EPC. Causes of insertion sequences abundance in prokaryotic genomes. Mol Biol Evol. 2007;24:969–981. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msm014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner A. Periodic extinctions of transposable elements in bacterial lineages: evidence from intragenomic variation in multiple genomes. Mol Biol Evol. 2006;23:723–733. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msj085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaghloul L, et al. The distribution of insertion sequences in the genome of Shigella flexneri strain 2457T. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2007;277:197–204. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2007.00957.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]