Abstract

The pathophysiological role of the neurosteroid 3α-hydroxy-5α-pregnan-20-one (allopregnanolone) in neuropsychiatric disorders has been highlighted in several recent investigations. For instance, allopregnanolone levels are decreased in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) of patients with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and major unipolar depression. Neurosteroidogenic antidepressants, including fluoxetine and analogs, correct this decrease in a manner that correlates with improved depressive symptoms.

PTSD-like behavioral dysfunctions, including heightened aggression, exaggerated fear, and anxiety-like behavior associated with a decrease in corticolimbic allopregnanolone content are modeled in mice by protracted social isolation stress. Allopregnanolone is not only synthesized by principal glutamatergic and GABAergic neurons but also locally, potently, positively, and allosterically modulates GABA action at post- and extra-synaptic GABAA receptors. Hence, this paper will review preclinical studies which show that in socially-isolated mice, rather than SSRI mechanisms, allopregnanolone biosynthesis in glutamatergic corticolimbic neurons offers a non-traditional target for fluoxetine to decrease signs of aggression, normalize fear responses, and decrease anxiety-like behavior. At low SSRI-inactive doses, fluoxetine and related congeners potently increase allopregnanolone levels by acting as potent selective brain steroidogenic stimulants (SBSSs), thereby facilitating GABAA receptor neurotransmission and improving behavioral dysfunctions.

Although the precise molecular mechanisms that underlie the action of these drugs are not fully understood, findings from socially-isolated mice may ultimately generate insights into novel drug targets for the treatment of psychiatric disorders, such as anxiety and panic disorders, depression, and PTSD.

Keywords: Allopregnanolone, 5α-reductase type I, selective brain steroidogenic stimulants (SBSSs), aggressive behavior, GABAA receptors, social isolation, anxiety, PTSD, mouse

Introduction

For almost half a century, it has been proposed that serotonin reuptake inhibition is the main molecular mechanism responsible for the anxiolytic, antipanic, antidysphoric, and antidepressant action of SSRIs (Wong et al., 1993; Bunney and Davis, 1965; Schildkraut, 1965; Hirschdeld, 2000; Mongeau et al., 1997; Burke, 2004). However, several reports have argued with this hypothesis and in recent years, studies have suggested that the so called “SSRI antidepressants” may exert their therapeutic actions by interacting on other neurochemical paramenters unrelated to their intrinsic selective serotonin reuptake inhibitory activity (Nestler et al., 2002; Castrén, 2005; Castrén and Rantamäki, 2010; Aboukhatwa and Undieh, 2010; Castro et al., 2010; Santarelli et al., 2003).

The observation that a single dose of fluoxetine and paroxetine potently, dose dependently, and region-selectively increase the content of the GABAA receptor-active neurosteroid allopregnanolone in various brain areas (olfactory bulb>frontal cortex>hippocampus>cerebellum>striatum) of adrenelectomized/castrated rats, led to the suggestion that an increase of brain allopregnanolone content may be part of the mechanism for the pharmacological actions of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) (Uzunov et al., 1996; Guidotti and Costa, 1998). Furthermore, fluoxetine and paroxetine selectively increased the levels of allopregnanolone but not those of the immediate precursor of allopregnanolone, 5α-dihydroprogesterone (5α-DHP) and also failed to change the levels of allopregnanolone in plasma, which suggests a specific brain-operated mechanism for fluoxetine that may be independent of peripheral steroid renovation sources (Uzunov et al., 1996).

Meanwhile, a role for CSF or serum allopregnanolone levels has been reported in several psychiatric conditions, ranging from post-partum depression and prementrual dysphoria, to schizophrenia and anxiety-related spectrum disorders, including panic and posttraumatic stress disorders (PTSD), and major depression (Rasmusson et al., 2006; Nappi et al., 2001; Strole et al., 2002; Rapkin et al., 1997; Marx et al., 2009; Pearlstein, 2010; Amin et al., 2006; Backstrom et al., 2003; Bloch et al., 2000).

In PTSD, the CSF levels of allopregnanolone, 5α-DHP, dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA: a negative modulator of GABAA receptor function), and progesterone were measured in premenopausal women with and without PTSD (Rasmusson et al., 2006). There were no group differences in progesterone, 5α-DHP, or DHEA levels. However, whereas the CSF levels of allopregnanolone were 40 fmol/ml in non-PTSD subjects, the PTSD group allopregnanolone levels were ~40% of healthy group levels (Rasmusson et al., 2006). This allopregnanolone/DHEA ratio correlated negatively with PTSD re-experiencing symptoms and with Profile of Mood State depression/dejection scores. These results suggest that low CSF allopregnanolone levels in premenopausal women with PTSD may contribute to an imbalance in inhibitory versus excitatory neurotransmission, resulting in increased PTSD re-experiencing and depressive symptoms (Rasmusson et al., 2006). Of note, this study also reported that allopregnanolone levels, which decreased in the whole PTSD group, reached their lowest levels in patients with PTSD and comorbid depression (Rasmusson et al., 2006).

The concept that an increase of allopregnanolone bioavailability contributes to the anxiolytic and antidepressant actions of fluoxetine and other SSRIs is supported by the observation that allopregnanolone levels, measured in four cisternal-lumbar fractions in the CSF before and 8–10 weeks after treatment with fluoxetine or fluvoxamine in 15 patients with unipolar major depression, were about 60% lower (~15 fmol/ml) in patients with major depression (Uzunova et al., 1998). However, in the same patients, treatment with fluoxetine or fluvoxamine normalized CSF allopregnanolone content to control values (~40 fmol/ml). Moreover, a statistically significant correlation existed between symptomatology improvement (Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression scores) and the increase in CSF allopregnanolone after fluoxetine or fluvoxamine treatment (Uzunova et al., 1998). The CSF content of pregnenolone and progesterone remained unaltered after SSRI treatment and failed to correlate with the fluoxetine or fluvoxamine-induced increase of CSF allopregnanolone (Uzunova et al., 1998). The normalization of CSF allopregnanolone content in depressed patients appeared to be sufficient to mediate the anxiolytic and antidysphoric actions of fluoxetine or fluvoxamine, via its positive allosteric modulation of GABAA receptors (Uzunova et al., 1998).

This pioneering discovery of Uzunova and colleagues (1998) remains one of the best-reported investigations in the field of neurosteroids and psychiatric disorders, for a number of reasons. For instance, allopregnanolone levels were measured in the CSF, rather than in the serum, which may not reflect allopregnanolone biosynthesis occurring in the brain. Further, the levels of CSF allopregnanolone in normal subjects and unipolar depressed patients were correlated with each patient’s behavioral symptoms. Most importantly, this investigation reported a correlation between the levels of CSF allopregnanolone and behavioral symptoms pre- and post-treatment with fluoxetine and fluvoxamine (Uzunova et al., 1998). A number of other investigations confirmed Uzunova’s findings in the serum of depressed patients following antidepressant therapy (Romeo et al., 1998; reviewed in Longone et al., 2008; Eser et al., 2006; Uzunova et al., 2006; Pinna et al., 2006a; Pisu and Serra, 2004)

The clinical data described above led to the hypothesis that decreased CSF levels of allopregnanolone could reflect a dysfunction of the rate-limiting step-enzyme of allopregnanolone biosynthesis, 5α-reductase type I (5α-RI), in a patient’s corticolimbic structures. Thus, a study was undertaken to evaluate the expression of 5α-RI mRNA in prefrontal cortical area BA9 and cerebellum from depressed patients that were age- and sex-matched with non-psychiatric subjects (Agis-Balboa et al., 2009). In depressed patients, the mRNA expression levels of 5α-RI were strongly decreased compared to those of normal subjects (Agis-Balboa et al., 2009). In contrast, 5α-RI failed to change in the cerebellum of depressed patients (Agis-Balboa et al., 2009).

Mood disorders, including anxiety and fear, can be modeled in mice to study anxiolytic and antidepressant drugs. This paper reviews preclinical studies, in animal models of anxiety-like behavior, including PTSD, which suggest that fluoxetine and congeners exert pharmacological effects via stimulation of neurosteroid biosynthesis rather than by inhibiting serotonin reuptake.

Role of neurosteroids as endogenous modulators of GABAA receptors

In the central nervous system (CNS), neurosteroids are synthesized independently from peripheral sources (adrenals and testis) (Baulieu, 1981; Baulieu et al., 2001; Cheney et al., 1995; Guidotti et al., 2001; Stoffel-Wagner, 2001). Hence, the term “neurosteroid” is applied to those steroids that are specifically synthesized in the brain, where they reach physiological significant levels to modulate gene expression and neurotransmitter systems (Puia et al., 1990; 1991; 2003; Pinna et al., 2000; Lambert et al., 2003; 2009; Belelli et al., 2005; Majewska et al., 1992). Several pharmacological studies have indicated that allopregnanolone expresses anticonvulsant, anxiolytic, antidepressant, and even sedative-hypnotic actions (D’aquila et al., 2010; Nin et al., 2008; Rodriguez-Landa et al., 2009; Kita and Furukawa, 2008; Lonsdale and Burnham, 2007; Mares et al., 2006; Martin-Garcia and Pallares, 2005; Jain et al., 2005). These effects resemble those elicited by several positive allosteric modulators of GABA action at GABAA receptors, including barbiturates and benzodiazepines (Guidotti et al., 2001; Majewska et al., 1992), and thus, these effects define allopregnanolone as a “neuroactive steroid”.

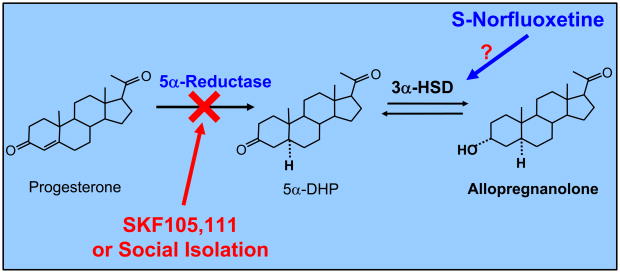

This review will focus on allopregnanolone, which is produced widely in several brain areas from progesterone metabolism (Pinna et al., 2000; Dong et al., 2001). As indicated in figure 1, progesterone is metabolized by the sequential action of two enzymes, 5α-RI, which transforms progesterone into 5α-dihydroprogesterone (5α-DHP), and 3α-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase (3α-HSD), which reduces 5α-DHP into allopregnanolone in a reversible manner (Dong et al., 2001).

Figure 1.

Allopregnanolone biosynthesis from progesterone in corticolimbic neurons. The 5α-reductase type I specific competitive inhibitor SKF 105,111 or social isolation decrease corticolimbic allopregnanolone levels, which triggers a reduced GABAA receptor neurotransmission. The mechanism whereby the potent selective brain steroidogenic stimulant (SBSS) S-norfluoxetine upregulates allopregnanolone levels is not clearly understood. A direct 3α-HSD activation by S-norfluoxetine has been previously suggested (Griffin and Mellon, 1999). 5α-DHP: 5α-dihydroprogesterone; 3α-HSD: 3α-hydroxy steroid dehydrogenase.

The distribution and the content of 5α-DHP and allopregnanolone in various brain regions is not uniform (Pinna et al., 2000; Dong et al., 2001). In rodents, the olfactory bulb shows the highest concentrations of 5α-DHP and allopregnanolone, followed by the frontal cortex, hippocampus, amygdala, striatum, and cerebellum (Pibiri et al., 2008). 5α-DHP exerts a genomic action and interacts with high affinity with the intracellular progesterone receptors (Rupprecht and Holsboer, 1999). On the other hand, allopregnanolone acts as a potent (nM affinity) positive allosteric modulator of the action of GABA at GABAA receptors, where it potentiates the intensity of GABA-gated Cl currents (Puia et al., 1990, 1991, 2003; Lambert et al., 2003; 2009). The physiological relevance of endogenous allopregnanolone is substantiated by the finding that this neurosteroid not only potentiates the inhibitory signals resulting from the release of GABA acting on GABAA receptors, but it also plays a facilitatory permissive role in fine-tuning the efficacy of direct receptor activators such as muscimol or that of other positive allosteric modulators of GABA action at GABAA receptors, including benzodiazepines and barbiturates (Matsumoto et al., 1999; 2003; Pinna et al., 2000; Guidotti et al., 2001; Puia et al., 2003).

Two discrete binding sites in the transmembrane domains of the GABAA receptor, that mediate the potentiation and direct activation effects of allopregnanolone, have recently been identified (Hosie et al., 2006). This study, for the first time, has clarified that allopregnanolone potentiates GABA responses from a cavity formed by the α-subunit transmembrane domains, whereas direct receptor activation is initiated by interfacial residues between the α and β subunits (Hosie et al., 2006). GABAA receptor activation is greatly enhanced when allopregnanolone binds to the potentiation site (Hosie et al., 2006). These authors demonstrate that significant receptor activation by allopregnanolone relies on occupancy of both the activation and potentiation sites (Hosie et al., 2006). The identification of these sites, which are highly conserved throughout the GABAA receptor family, opens new avenues for neurosteroid pharmacological studies.

Recent studies reported that GABAA receptors incorporating α4, α6, and δ subunits in combination with γ and β subunits may have a higher affinity for neurosteroids than other recombinant GABAA receptor subtypes that express different subunit combinations (Belelli et al., 2002; Belelli and Lambert, 2005). However, the affinity of neurosteroids for these GABAA receptor subtypes remains in the low nM range (Puia et al., 1990; 1991). Thus, neurosteroid allosteric positive modulators of the action of GABA at GABAA receptors show a pharmacological profile much less differentiated than that of the GABAA receptor modulation by benzodiazepines, which have low intrinsic activity at GABAA receptor-containing α4 or α6 subunits (Puia et al., 1990, 1991; Vicini et al., 1991; Costa and Guidotti,1996).

In corticolimbic circuit neurons, local neurosteroid bioavailability modulates GABAA receptors

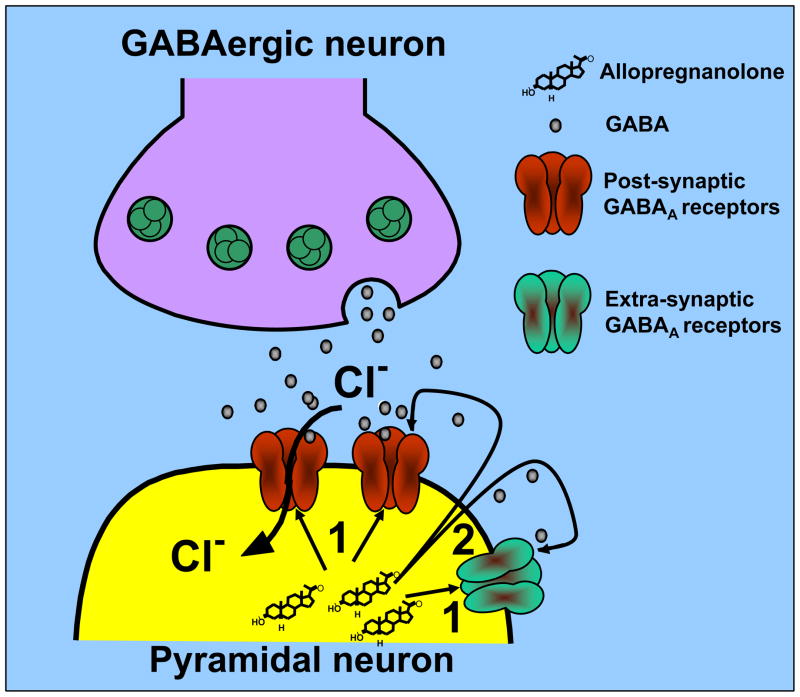

A recent immunohistochemistry study has clarified the neuronal localization of the neurosteroidogenic enzymes 5α-RI and 3α-HSD, and has provided a new understanding of how allopregnanolone is produced in neurons and is secreted locally to reach and activate post- and extrasynaptic GABAA receptors (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Physiological levels of allopregnanolone maintain the function of GABAergic neurotransmission in the brain (Pinna et al., 2000). This diagrammatic representation depicts the local action of allopregnanolone on GABAA receptors located on synaptic membranes of pyramidal neurons. GABA released from GABAergic interneurons activates a family of postsynaptic and extrasynaptic GABAA receptors. Allopregnanolone may facilitate the synaptic inhibitory action of GABA at postsynaptic and extrasynaptic GABAA receptors by an autocrine mechanism (arrow 1) or may access GABAA receptors by acting at the intracellular sites (arrow 2) of the GABAA receptors.

The enzymes 5α-RI and 3α-HSD were shown to be highly expressed and to co-localize in a region-specific way in primary GABAergic and glutamatergic output neurons, including pyramidal neurons, granular cells, reticulo-thalamic neurons, medium spiny striatum and nucleus accumbens neurons, and Purkinje neurons, but are virtually absent in GABAergic cortical interneurons and glial cells (Agis-Balboa et al., 2006).

Long projecting primary GABAergic neurons located in the reticular thalamic nucleus, which express high levels of 5α-RI and 3α-HSD, are likely to secrete allopregnanolone at the time that they release GABA to target postsynaptic GABAA receptors incorporated in dendrites and somata of glutamatergic thalamocortical neurons (Pinault, 2004). Likewise, it is suggested that allopregnanolone synthesized by medium spiny GABAergic striatal neurons, as well as allopregnanolone that is produced by cerebellum Purkinje cells, may activate postsynaptic GABAA receptors located on cell bodies or dendrites of neurons in deep cerebellar nuclei.

Allopregnanolone synthesized in glutamatergic cortical or hippocampal pyramidal neurons. or in granular cells of the dentate gyrus, may be secreted in a paracrine fashion to reach distal GABAA receptors inserted in cell bodies or dendrites of cortical or hippocampal pyramidal neurons (Fig. 2). In addition, allopregnanolone may act locally by reaching postsynaptic or extrasynaptic GABAA receptors located on the same dendrites or cell bodies of the cortical or hippocampal pyramidal neuron itself that has produced allopregnanolone (Agis-Balboa et al., 2006). Lastly, allopregnanolone might not be released, but may access GABAA receptors located on the cell bodies or dendritic arborization of glutamatergic neurons, acting at the intracellular sites of the GABAA receptors, by lateral diffusion into plasma membranes (Akk et al., 2005; Agis-Balboa et al., 2006) (Fig. 2).

The modality of local allopregnanolone region and neuron-specific biosynthesis and release, and its action on GABAA receptors, suggest that this neurosteroid may not only ensure a proper activation of GABAA receptors in physiological conditions, but at the same time may represent a biomarker that can be targeted in psychiatric disorders characterized by a dysfunction of GABAergic neurotransmission.

Role of allopregnanolone in the regulation of aggressive behavior, anxiety, and excessive fear induced in mice by social isolation

Allopregnanolone has emerged as an important regulator of behavioral deficits induced in rodent models of depression and anxiety spectrum disorders (Uzunova et al., 2004; Pibiri et al., 2008).

In the author’s laboratory, a mouse model characterized by a downregulation of allopregnanolone biosynthesis, induced by a protracted social isolation stress, has been adopted to establish the fundamental role of allopregnanolone in the regulation of contextual fear, anxiety-like behavior, and aggression (Matsumoto et al., 1999; Dong et al., 2001; Pinna et al., 2003a, 2006a; Pibiri et al., 2008; Nelson and Pinna, 2010). In male mice socially isolated for a period of four weeks, we have previously demonstrated a time-dependent increase of aggressive behavior at the same time that corticolimbic allopregnanolone levels were decreased (Pinna et al., 2003a). Likewise, using Pavlonian fear conditioning, during which mice were exposed in a novel environment (i.e., the context) to the administration of an acoustic tone (the conditionined stimulus) and the unconditioned stimulus of a footshock, mice exhibited a conditioned fear response comprising enhanced freezing time 24 h following the training section (Pibiri et al., 2008; Pinna et al., 2008). In socially-isolated mice, there was a time-related increase of contextual fear conditioning responses that was inversely correlated with the decay of 5α-RI expression determined in the hippocampus and amygdala (Pibiri et al., 2008). Fear conditioning responses, similar to aggressive behavior, increased during the four weeks and a plateau was reached between four and eight weeks of social isolation (Pinna et al., 2003a; Pibiri et al., 2008). In a fear conditioning extinction trial, freezing time declined rapidly over the first three days, during which mice were repeatedly exposed to the context chamber; however, the socially-isolated mice showed: 1) higher levels of contextual freezing time on day 1 of exposure to the chamber and 2) a delayed extinction. The contextual fear extinction in socially-isolated mice failed to reach the low values of the group-housed control mice, suggesting that in socially-isolated mice, fear extinction is not only delayed but also incomplete (Pibiri et al., 2008). In accord with these results, we had previously shown that socially-isolated mice exhibited higher levels of anxiety-like behavior, determined in the elevated plus maze and in the open field (Pinna et al., 2006a).

Evidence collected in our laboratory supports the concept that corticolimbic allopregnanolone plays a pivotal role in the regulation of contextual fear conditioning and aggression (Pinna et al., 2003a, 2006a; Pibiri et al., 2008; Nelson and Pinna, 2010). Hence, as a proof of concept, experiments were undertaken, which showed that administration of allopregnanolone dose-dependently attenuates the duration of attacks toward a male intruder (Pinna et al., 2003a; 2006a). The attenuation of aggression is accompanied by an upregulation of cortico-limbic allopregnanolone content (Pinna et al., 2003; 2006a; Matsumoto et al., 2007). Likewise, single injections of allopregnanolone normalized the exaggerated contextual fear responses expressed by socially-isolated mice (Pibiri et al., 2008).

Other groups have demonstrated that allopregnanolone elicits antianxiety properties (Rodgers and Jonhson, 1998; Frye et al., 2006; Bitran et al., 1991; Wieland et al., 1991), when administered systemically or by direct infusion into target corticolimbic areas, including the basolateral amygdala, central amygdala, hippocampus, and prefrontal cortex (Nelson and Pinna, 2010; Deo, et al., 2010; Engin and Treit, 2007). In addition, inhibiting allopregnanolone biosynthesis in the midbrain VTA has been shown to reduce the anti-anxiety properties of allopregnanolone, an action which can be reversed by administering neurosteroidogenic drugs, including FGIN 1–27 (Frye et al., 2009).

A brain region-specific downregulation of 5α-RI in socially-isolated mice has been revealed by the application of RT-PCR to determine the expression levels of 5α-RI in various brain structures that include neurons with intense neurosteroidogenesis (Agis Balboa et al., 2007; Pibiri et al., 2008). The highest decrease of 5α-RI was found in the amygdala and hippocampus, followed by the olfactory bulb and the frontal cortex (Pibiri et al., 2008). On the other hand the expression of 5α-RI failed to change in the cerebellum and striatum (Pibiri et al., 2008). Similarly, using gas chromatography mass fragmentography to detect picomolar amounts of allopregnanolone in discrete brain structures, we confirmed that the decrease of 5α-RI in the above-mentioned brain areas resulted in a massive reduction of the levels of allopregnanolone (Pibiri et al., 2008). In situ immunohistochemical studies conducted in socially-isolated and group-housed mice have demonstrated that 5α-RI is specifically decreased in cortical pyramidal neurons of layers V–VI, in hippocampal CA3 pyramidal neurons and glutamatergic granular cells of the dentate gyrus, as well as in the pyramidal-like neurons of the basolateral amygdala (Agis-Balboa et al., 2007). However, 5α-RI fails to change in primary GABAergic neurons of the reticular thalamic nucleus, central amygdala, cerebellum, and in the medium spiny neurons of the caudatus and putamen (Agis-Balboa et al., 2007).

To examine the hypothesis that cortico-limbic allopregnanolone level downregulation is responsible for the aggressive behavior and enhanced conditioned fear responses found in socially-isolated mice, we administered the potent 5α-RI competitive inhibitor SKF 105,111 to normal group-housed mice (Pinna et al., 2000, 2008; Cheney et al., 1995). SKF 105,111 rapidly (~1 h) decreased levels of allopregnanolone in the olfactory bulb, frontal cortex, hippocampus, and amygdala to 80% of their original levels (Pinna et al., 2008; Pibiri et al., 2008). This decrease of allopregnanolone is maintained up to six hours (Pinna et al., 2008) and results in a downregulation of GABAA receptor responsiveness to direct receptor activators or positive allosteric modulators of GABA action at GABAA receptors, including pentobarbital, muscimol, ethanol, and benzodiazepine, or to GABAA receptor antagonists such as picrotoxin (Matsumoto et al., 1999; Pinna et al., 2000; Guidotti et al., 2001; Matsumoto et al., 2003).

Consistent with the above mentioned results, administration of SKF 105,111 two hours before contextual fear-conditioning training induced a dose-dependent increase of contextual fear-conditioning responses that negatively correlated with depletion of hippocampal allopregnanolone level (Pibiri et al., 2008). The effects of SKF 105,111 on contextual fear responses were reversed by administering allopregnanolone doses that normalized hippocampus allopregnanolone levels (Pibiri et al., 2008).

Protracted social isolation in mice as a mouse model relevant for PTSD

Several behavioral and neurochemical alterations that are commonly found in PTSD patients can be reproduced by protracted social isolation in mice.

First, a downregulation of the CSF levels of allopregnanolone that correlates with negative reexperiencing symptoms was demonstrated in PTSD premenopausal women with comorbid depressive symptoms (Rasmusson et al., 2006). Socially-isolated mice express a downregulation of corticolimbic allopregnanolone levels in pivotal regions for the regulation of emotional behaviors, including the medial frontal cortex, hippocampus, and the basolateral amygadala (Agis-Balboa et al., 2007; Pibiri et al., 2008; reviewed in Pinna et al., 2008).

Second, the expression of impulsive aggression and violence is heightened in combat veterans (Forbes et al., 2008). Accordingly, one of the best-characterized behavioral deficits of socially-isolated mice are the very high levels of aggression (Garattini et al., 1967; Valzelli, 1981; Pinna et al., 2003a; reviewed in Pinna et al., 2008).

Further, in PTSD patients, there were enhanced contextual fear-conditioning responses, and impaired extinction of fear was evident when these patients were re-exposed to the events that symbolize the triggering traumatic event; however, cued fear conditioning was not changed (Rausch et al., 2006; Ameli and Grillon, 2001; Grillon and Morgan, 1999). Socially-isolated mice analogously display exaggerated contextual fear conditioning and delayed and incomplete fear extinction with unchanged cued fear conditioning (Pibiri et al., 2008).

Finally, PTSD patients fail to respond to the anxiolytic and sedative properties of benzodiazepines (Viola et al., 1997; Davidson, 2004; Gelpin et al., 1996). Balkan and Vietnam war veterans also show a decreased fronto-cortical benzodiazepine recognition site binding (Geuze et al., 2008; Bremner et al., 2000). Of note, we found a lack of sedative (Pinna et al., 2006b) and anxiolytic (Pinna, G, unpublished) activity of diazepam and zolpidem in mice that were socially isolated for up to four weeks. The effect appeared to be mediated by changes in the expression of several GABAA receptor subunits, including a decrease of α1, α2, and γ2 and an increase of α4 and α5 subunits (Pinna et al., 2006b). These changes were accompanied by a decrease of [3H]flumazenil binding to hippocampal synaptic membranes (Pinna et al., 2006b). These results are in agreement with a previous study, which reported brain benzodiazepine receptor changes in socially-isolated mice (Essman and Valzelli, 1981).

In summary, although the initial mechanism whereby social isolation in mice decreases corticolimbic allopregnanolone levels may be different from the mechanism that decreases CSF allopregnanolone levels following traumatic events in PTSD patients, the behavioral effects of protracted corticolimbic allopregnanolone deficiency and the resulting GABAergic neurotransmission deficit in socially-isolated mice resemble those observed in PTSD patients.

Selective brain steroidogenic stimulants (SBSSs) upregulate corticolimbic allopregnanolone levels and reverse behavioral deficits in socially isolated mice

As discussed earlier fluoxetine and fluvoxamine may improve depressive symptoms by upregulating brain allopregnanolone levels (Uzunova et al., 1998). Also, fluoxetine and paroxetine were shown to induce increases in olfactory bulb and frontal cortex allopregnanolone content in rodents (Uzunov et al., 1996; Matsumoto et al., 1999). With these findings in mind, we designed several studies to demonstrate in a mouse model of PTSD that the beneficial behavioral effects of SSRIs were indeed exerted by the neurosteroidogenic upregulation of corticolimbic allopregnanolone levels, rather than their intrinsic activity as serotonin reuptake inhibitors.

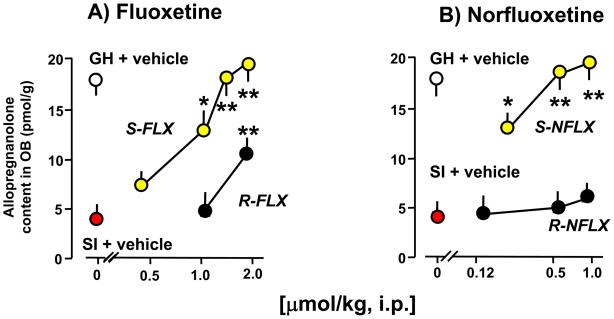

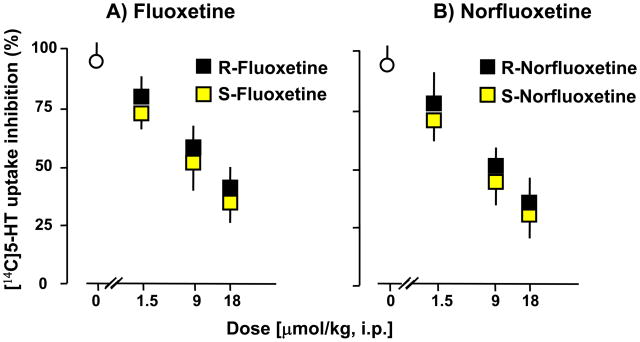

Since fluoxetine is an S and R racemic mixture that is metabolized into S- or R-norfluoxetine (Potts and Parli, 1992), we tested the ability of these drugs to stereospecifically upregulate corticolimbic allopregnanolone content or to inhibit serotonin reuptake. Part of this hypothesis was that fluoxetine and norfluoxetine stereoisomers doses that change corticolimbic allopregnanolone content may differ from those that inhibit 5-HT reuptake. Table 1 and Fig. 3 show that fluoxetine and norfluoxetine, in submicromolar doses and in a stereospecific manner, reverse the decrease of corticolimbic allopregnanolone levels caused by social isolation. The S-stereoisomers of fluoxetine or norfluoxetine are several fold more potent than their respective R-stereoisomers (Fig. 3 and Table 1). S-norfluoxetine is about 5-fold more potent than S-fluoxetine. Importantly, the effective concentrations 50% (EC50s) of S-fluoxetine and S-norfluoxetine that normalize the brain allopregnanolone content are 10- (S-fluoxetine) and 50-fold (S-norfluoxetine) lower than their respective EC50s needed to inhibit 5-HT reuptake (Table 1 and Fig. 4).

Table 1.

Fluoxetine and norfluoxetine stereoisomers induce normalization of pentobarbital (PTB) right reflex loss (RRL), reduce the duration of attacks against an intruder (Aggression), activate neurosteroidogenesis (Allo) at doses that fail to affect 5-HT reuptake.

| Mice | PTB-RRL (EC50, μmol/kg) | Aggression (EC50, μmol/kg) | Allo (EC50, μmol/kg) | 5-HT Reuptake (EC50, μmol/kg) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| S-Fluoxetine | 0.70±0.2* | 0.71±0.03 * | 0.80±0.07* | 10.5±2.4 |

| R-Fluoxetine | >1.80 | 1.30±0.02 | >1.80 | 13.7±3.2 |

| S-Norfluoxetine | 0.25±0.1** | 0.20±0.08** | 0.15±0.03** | 8.3±3.1 |

| R-Norfluoxetine | 1.70±0.3 | 1.53±0.20 | >0.9 | 10.1±3.8 |

Drugs were administered 30 min before behavioral tests and [14C]5-HT reuptake measurement. Data represent the mean ± SEM of four to six mice socially isolated for 4 weeks before testing.

P<0.01 when S-fluoxetine is compared with R-fluoxetine.

P<0.001 when S-norfluoxetine is compared with R-norfluoxetine and S-fluoxetine.

The EC50 were calculated from dose-response curves analyzed by the “quantal dose-response: probits test” (Tallarida and Murray, 1987) equipped with a statistical package. Statistical comparisons among the different IC50 values were performed by using the COHORT package. For details see Pinna et al., (2003a, 2004a, 2009)

Figure 3.

Increase of allopregnanolone levels in the olfactory bulb of socially-isolated (SI) mice after treatment with fluoxetine (FLX) and norfluoxetine (NFLX) stereoisomers. R- and S-fluoxetine (A) and R- and S-norfluoxetine (B) were given 30 min before allopregnanolone determination. P values are from the comparison of R- and S-fluoxetine-treated and R- and S-norfluoxetine-treated socially-isolated mice with vehicle (VH)-treated socially-isolated mice. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01. Each value is the mean ± SEM of six mice. GH= Group housed mice. For details see Pinna et al., (2004).

Figure 4.

Ex vivo inhibition of serotonin reuptake in cortical slices from socially-isolated mice treated with stereoisomers of fluoxetine (A) and norfluoxetine (B). Drugs were administered 30 min before ex vivo [14C] 5-HT uptake measurements. Each value represents the mean ± SEM of four mice. For details see Pinna et al., (2004).

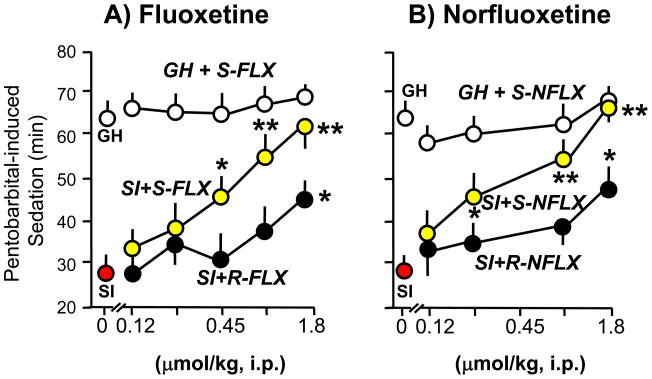

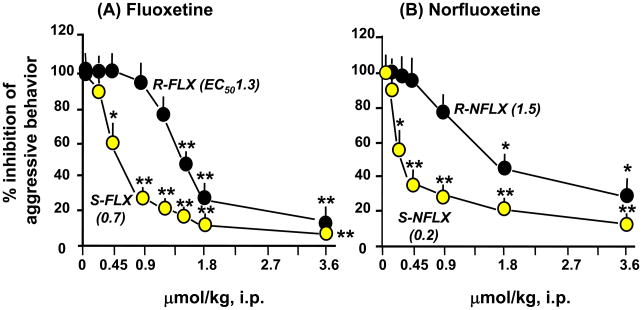

The possibility that fluoxetine and its congeners could abolish the behavioral deficits associated with protracted social isolation by increasing brain allopregnanolone content, rather than by a mechanism involving serotonin reuptake inhibition, was tested by measuring aggressiveness and changes in sedation induced by pentobarbital in socially-isolated male mice. Fluoxetine dose-dependently and stereospecifically normalized the duration of pentobarbital-induced sedation (Fig. 5) and reduced aggressiveness (Fig. 6) at the same doses that also normalized the downregulation of brain allopregnanolone content in socially-isolated mice (Table 1).

Figure 5.

Fluoxetine (FLX) and norfluoxetine (NFLX) stereospecifically normalize the duration of pentobarbital-induced sedation in socially-isolated (SI) mice. R- and S-FLX (A) and R- and S-NFLX (B) were given 30 min before pentobarbital (50 mg/kg, i.p.). P values are from the comparison of FLX- or NFLX-treated SI mice with vehicle (VH)-treated SI mice. *, P 0.05; **, P 0.01. Each value is the mean ± SEM of six to eight mice. For details see Pinna et al., (2004).

Figure 6.

Fluoxetine (FLX) and norfluoxetine (NFLX) dose-dependently suppress social isolation-induced aggressive behavior (% of vehicle-treated mice) in a stereospecific manner. Each point is the mean ± S.E.M. of 8–12 mice. Drugs were given 30 min before test. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01, when FLX-or NFLX-treated mice were compared with vehicle-treated mice. For details see Pinna et al. (2003a).

Similarly, the actions of norfluoxetine are stereospecific (S-norfluoxetine>R-norfluoxetine) and are about three-fold more potent than fluoxetine, both in normalizing pentobarbital-induced sedation and in inhibiting the aggressive behavior induced by social isolation in male mice (Fig. 5 and 6, and Table 1). These actions are paralleled by increases in corticolimbic allopregnanolone levels (Fig. 3 and Table 1). The potency of S-norfluoxetine in normalizing the duration of pentobarbital-induced sedation and inhibiting aggression is seven-fold higher than that of the R-isomer (Table 1). At these low doses, S-norfluoxetine efficiently normalized the exaggerated contextual fear conditioning responses and anxiety-like behavior of socially isolated mice (Pinna et al., 2006; Pibiri et al., 2008).

Most importantly, this study also showed that the action of S-fluoxetine and S-norfluoxetine on pentobarbital-induced sedation, the inhibition of aggression, or the normalization of corticolimbic allopregnanolone content, cannot be related to their intrinsic SSRI activity. In fact: 1) the EC50s of S-fluoxetine and S-norfluoxetine in normalizing pentobarbital-induced sedation, reducing aggression, and upregulating corticolimbic allopregnanolone levels in socially-isolated mice are at least 10–50 times lower than the EC50 required to inhibit 5-HT reuptake (Table 1); and 2) SSRI activity of S- or R-fluoxetine and of S- or R-norfluoxetine is devoid of stereospecificity (Table 1). In addition to the direct evidence provided by the above-detailed experiments, we have found indirect evidence that favors a selective brain steroidogenic stimulant (SBSS) role of the so-called “SSRI”, fluoxetine and norfluoxetine: 1) doses of imipramine that inhibit serotonin reuptake fail to reduce aggression and to normalize the decreased corticolimbic allopregnanolone levels of socially-isolated mice (Pinna et al., 2003a); 2) The antidepressant tianeptine, which acts on the glutamatergic system (McEwen et al., 2010) and is devoid of SSRI activity (Mennini et al., 1987), also increased olfactory bulb allopregnanolone levels and decreased social isolation-induced aggression (Pinna et al., 2003b); and 3) P-chlorophenylalanine (P-CPA), in doses that reduced brain serotonin levels by >80%, failed to prevent the action of fluoxetine on pentobarbital-induced sedation or on the increase of corticolimbic allopregnanolone content in socially-isolated mice (Matsumoto et al., 1999).

Hence, the serotonin reuptake inhibition elicited by the S stereoisomers of fluoxetine and norfluoxetine is not operative in decreasing social isolation-induced aggression, potentiating pentobarbital-induced sedation or normalizating downregulated corticolimbic allopregnanolone levels.

In accord with these results are findings obtained using the olfactory bulbectomized rat model of depression, in which allopregnanolone levels are downregulated in several corticolimbic structures (Uzunova et al., 2003; reviewed in 2006). In these studies, a number of antidepressants, including fluoxetine, sertraline, and venlafaxine were found to potently reverse the decline of allopregnanolone content induced by bilateral bulbectomy in selected cerebrocortical regions (Uzunova et al., 2004).

Mechanisms by which neurosteroidogenic antidepressants increase neurosteroids

The mechanism by which fluoxetine and norfluoxetine or other neurosteroidogenic antidepressants (i.e., paroxetine, fluvoxamine, sertraline) increase corticolimbic allopregnanolone levels in socially-isolated mice or in bulbectomized rats remains unclear. The high potency and stereospecificity of these drugs in reducing behavioral deficits and in normalizing brain allopregnanolone content suggest that they may affect specific targets for neurosteroidogenesis.

The finding that protracted social isolation affects the expression of 5α-RI in corticolimbic structures but fails to change the expression of 3α-HSD (Dong et al., 2001; Agis-Balboa et al., 2007; Pibiri et al., 2008) and that brain progesterone levels fail to change in socially-isolated mice suggests that a mechanism involving 5α-RI is responsible for the decrease of corticolimbic allopregnanolone content. This is additionally supported by the fact that 5α-RI is the rate-limiting step-enzyme in allopregnanolone biosynthesis from progesterone (Dong et al., 2001). Hence, these data point to a possible fluoxetine and norfluoxetine-mediated upregulation of corticolimbic allopregnanolone levels by a direct action on 5α-RI.

Studies in vitro using recombinant rat 5α-RI showed that fluoxetine, paroxetine, and sertraline in concentrations as high as 50 μM failed to activate 5α-RI (Griffin and Mellon, 1999). However, they do directly activate 3α-HSD by decreasing its Km for 5α-DHP by 100-fold, and thereby facilitate the reduction of 5α-DHP into allopregnanolone (Griffin and Mellon, 1999). From studies, performed in socially-isolated mice, the doses of fluoxetine and norfluoxetine that cause a rapid increase in brain allopregnanolone levels reach brain concentrations in the low nM range, whereas the fluoxetine concentrations that directly activate 3α-HSD in vitro are in the μM range (Griffin and Mellon, 1999). Studies conducted by Uzunov and collegues (1996) showed that treatment with fluoxetine failed to alter allopregnanolone levels in plasma and that this drug selectively activated neurosteroidogenesis independently of peripheral steroidogenic input. The levels of 5α-DHP were unchanged or even decreased after fluoxetine and paroxetine administration, which supports the activation of 3α-HSD as the responsible mechanism (Uzunov et al., 1996). Furthermore, the hypothesis that neurosteroidogenic antidepressants may activate 3α-HSD is suggested by experiments in which preincubation with fluoxetine accelerated the rate of accumulation of allopregnanolone following incubation of brain slices with 5α-DHP (Uzunov et al. 1996). Unfortunately, the hypothesis that fluoxetine and paroxetine directly activate 3α-HSD has not been supported by more recent results (Trauger et al., 2002). It is feasible however, that the kinetics of 5α-RI and/or 3α-HSD may be altered in socially-isolated mice, and that these enzymes become susceptible to neurosteroidogenic antidepressants. This is suggested by the finding that low doses of the S isomers of fluoxetine or norfluoxetine increase the levels of allopregnanolone in socially-isolated mice but the same doses fail to change the corticolimbic levels of allopregnanolone in group-housed mice (Matsumoto et al., 1999; Pinna et al., 2003a). These observations require further investigation at the molecular enzymatic level. For example, it is important to determine whether these neurosteroidogenic agents affect 5α-RI and/or 3α-HSD activity by changing the affinity for substrate or cofactor.

Although brain progesterone levels are not affected by fluoxetine administration in group-housed or socially-isolated mice (Matsumoto et al., 1999), these drugs may still activate neurosteroidogenesis by a specific mechanism upstream from progesterone. For instance, an interaction with mitochondrial benzodiazepine (mBZD) receptors with the polypeptide diazepam binding inhibitor that binds to mBZD receptors and activates steroidogenesis (Costa and Guidotti, 1991) or with the expression of the steroidogenic acute regulatory protein (StAR) that transfers cholesterol to mBDZ receptors (Artemenko et al., 2001, Bose et al., 2002) is conceivable. Hence, among drugs that selectively stimulate neurosteroid biosynthesis and are devoid of intrinsic SSRI activity, one may consider agonists of “mitochondrial BZ receptors,” such as the indoleacetamide derivatives FGIN 1–27 and congeners (Romeo et al. 1992; Auta et al. 1993).

It cannot be excluded that fluoxetine and congeners could also change levels of enzyme expression by playing a role in the epigenetic regulation of 5α-RI operative during social isolation. Evidence for the epigenetic regulation of key steroidogenic enzymes is increasing (reviewed in Martinez-Arguelles and Papadopoulos, 2010). The 5′ upstream region of rat 5α-RI includes all the features of CpG islands and contains several potential binding sites for the transcription factor Sp1 (Chang and Chen, 2005; Chen et al., 2007; Safe and Kim, 2004). Sp1 is involved in the epigenetic control of the promoter activity regulating chromatin remodeling and favoring the propagation of methylation-free islands on gene promoters (Blanchard et al., 2007). Thus, the expression of 5α-RI could also be regulated through an epigenetic regulation of promoter hypermethylation that may trigger 5α-RI mRNA downregulation following long-term social isolation. In favor of this hypothesis are data showing a significant increase in the expression levels of fronto-cortical DNA methyltransferase-1 (DNMT1) mRNA in socially-isolated mice (Tueting et al., 2008). This finding suggests that social isolation may induce hypermethylation of the 5α-RI promoter and thereby downregulate 5α-RI expression and allopregnanolone levels. Therefore, it would be of interest to evaluate whether fluoxetine and norfluoxetine, either alone or in combination with inhibitors of DNMT1 (Kundakovic et al., 2007; Dong et al., 2007) or DNA-demethylase inducers (Costa et al., 2009; Dong et al., 2007, Tremolizzo et al., 2005) including valproate, reverse the social isolation-induced 5α-RI expression downregulation by an epigenetic mechanism. Valproate in combination with antipsychotics is currently being tested in clinical trials to treat psychiatric illness, such as schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, depression, and drug addiction (Guidotti et al., 2009; Tsankova et al., 2007). Such studies are important in the treatment of depression and PTSD because in these psychiatric disorders, allopregnanolone brain levels are downregulated (Uzunova et al., 1998; Rasmusson et al., 2006), probably because 5α-RI and/or 3α-HSD expression are epigenetically downregulated (Agis-Balboa et al., 2010).

Although the precise mechanism by which fluoxetine and norfluoxetine induce neurosteroidogenic effects in socially-isolated mice at low nM doses is unclear, studies involving neurosteroidogenic agents may help in the treatment of psychiatric disorders, including PTSD.

Conclusions

In the treatment of psychiatric disorders associated with GABAergic neurotransmission dysfunction mediated by a downregulation of brain allopregnanolone expression, such as in PTSD, the use of SBSSs appears to be the best selective and efficacious therapeutic strategy.

As reported above, the pharmacological spectrum of allopregnanolone as an allosteric modulator of GABA at GABAA receptors is broader than that of benzodiazepines, which fail to modulate GABAA receptors containing α4 and α6 subunits. The efficacy of allopregnanolone is expressed widely in several subtypes of GABAA receptors for doses in the low nM range. Hence, selective stimulation of allopregnanolone biosynthesis may avoid the therapeutic hindrances caused by GABAA receptors formed with altered subunit composition, such as may occur in stress-related psychiatric disorders (reviewed in Maguire and Mody, 2009).

Importantly, due to the brain region- and neuron-specific expression of 5α-RI and 3α-HSD, the action of SBSSs on neurosteroid biosynthesis targets specific brain structures and is neuron-specific. Hence, SBSSs, including S-norfluoxetine, may be devoid of the unwanted side effects that may be caused by a “neurosteroid replacement therapy” with direct systemic administration of allopregnanolone and congeners (Gee et al., 1988; Phillipps, 1975; Reddy and Woodward, 2004; Reddy and Rogawski, 2000; Smith et al., 1998).

Understanding the mechanism(s) whereby SBSSs increase corticolimbic allopregnanolone bioavailability and normalize stress-related behavioral symptoms may reveal a pharmacological target with important consequences in future drug development for the improvement of behavioral symptoms of PTSD.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by National Institute of Mental Health Grants MH 085999 (to G.P.).

References

- Aboukhatwa MA, Undieh AS. Antidepressant stimulation of CDP-diacylglycerol synthesis does not require monoamine reuptake inhibition. BMC Neurosci. 2010;27:11:10. doi: 10.1186/1471-2202-11-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agis-Balboa RC, Pinna G, Zhubi A, Maloku E, Veldic M, Costa E, Guidotti A. Characterization of brain neurons that express enzymes mediating neurosteroid biosynthesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:14602–14607. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0606544103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agis-Balboa RC, Pinna G, Kadriu B, Costa E, Guidotti A. Downregulation of 5α-reductase type I mRNA expression in cortico-limbic glutamatergic circuits of mice socially isolated for four weeks. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:18736–41. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0709419104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agis-Balboa RC, Guidotti A, Whitfield H, Pinna G. 2010 Neuroscience Meeting Planner. San Diego, CA: Society for Neuroscience; 2010. Allopregnanolone biosynthesis is downregulated in the prefrontal cortex/Brodmann’s area 9 (BA9) of depressed patients. [Google Scholar]

- Akk G, Shu HJ, Wang C, Steinbach JH, Zorumski CF, Covey DF, Mennerick S. Neurosteroid access to the GABAA receptor. J Neurosc. 2005;25:11605–11613. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4173-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ameli R, Ip C, Grillon C. Contextual fear-potentiated startle conditioning in humans: replication and extension. Psychophysiology. 2001;38:383–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Artemenko IP, Zhao D, Hales DB, Hales KH, Jefcoate CR. Mitochondrial processing of newly synthesized steroidogenic acute regulatory protein (StAR), but not total StAR, mediates cholesterol transfer to cytochrome P450 side chain cleavage enzyme in adrenal cells. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:46583–96. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M107815200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auta J, Romeo E, Kozikowski A, Ma D, Costa E, Guidotti A. Participation of mitochondrial diazepam binding inhibitor receptors in the anticonflict, antineophobic and anticonvulsant action of 2-aryl-3-indoleacetamide and imidazopyridine derivatives. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1993;265:649–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baulieu EE. Steroid hormones in the brain: several mechanisms. In: Fuxe K, Gustafson JA, Wettenberg L, editors. Steroid hormone regulation of the brain. Elmsford, NY: Pergamon; 1981. pp. 3–14. [Google Scholar]

- Baulieu EE, Robel P, Schumacher M. Neurosteroids: beginning of the story. Int Rev Neurobiol. 2001;46:1–32. doi: 10.1016/s0074-7742(01)46057-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belelli D, Casula A, Ling A, Lambert JJ. The influence of subunit composition on the interaction of neurosteroids with GABAA receptors. Neuropharmacology. 2002;43:651–61. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(02)00172-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belelli D, Lambert JJ. Neurosteroids: endogenous regulators of the GABAA receptor. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2005;6:565–575. doi: 10.1038/nrn1703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bitran D, Hilvers RJ, Kellogg CK. Anxiolytic effects of 3 alpha-hydroxy-5 alpha[beta]-pregnan-20-one: endogenous metabolites of progesterone that are active at the GABAA receptor. Brain Res. 1991;561:157–61. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(91)90761-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanchard Y, Seenundun S, Robaire B. The promoter of the rat 5a-reductase type 1 gene is bidirectional and Sp1-dependent. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2007;264:171–183. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2006.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bose HS, Lingappa VR, Miller WL. Rapid regulation of steroidogenesis by mitochondrial protein import. Nature. 2002;417:87–91. doi: 10.1038/417087a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bremner JD, Innis RB, Southwick SM, Staib L, Zoghbi S, Charney DS. Decreased benzodiazepine receptor binding in prefrontal cortex in combat-related posttraumatic stress disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157:1120–6. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.7.1120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bunney WE, Davis JM. Norepinephrine in depressive reactions. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1965;13:483–494. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1965.01730060001001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke WJ. Selective versus multi-transmitter antidepressants: Are two mechanisms better than one? J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65:37–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castrén E. Is mood chemistry? Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2005;6:241–246. doi: 10.1038/nrn1629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castrén E, Rantamäki T. The role of BDNF and its receptors in depression and antidepressant drug action: Reactivation of developmental plasticity. Dev Neurobiol. 2010;70:289–97. doi: 10.1002/dneu.20758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castro JE, Varea E, Márquez C, Cordero MI, Poirier G, Sandi C. Role of the amygdala in antidepressant effects on hippocampal cell proliferation and survival and on depression-like behavior in the rat. PLoS One. 2010;5:e8618. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang WC, Chen BK. Transcription factor Sp1 functions as an anchor protein in gene transcription of human 12(S)-lipoxygenase. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;338:117–121. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, Kundakovic M, Agis-Balboa RC, Pinna G, Grayson DR. Induction of the reelin promoter by retinoic acid is mediated by Sp1. J Neurochem. 2007;103:650–665. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2007.04797.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheney DL, Uzunov D, Costa E, Guidotti A. Gas chromatographic-mass fragmentographic quantitation of 3α-hydroxy-5α-pregnan-20-one (allopregnanolone) and its precursors in blood and brain of adrenalectomized and castrated rats. J Neurosci. 1995;15:4641–4650. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-06-04641.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa E, Chen Y, Dong E, Grayson DR, Kundakovic M, Maloku E, Ruzicka W, Satta R, Veldic M, Zhubi A, Guidotti A. GABAergic promoter hypermethylation as a model to study the neurochemistry of schizophrenia vulnerability. Expert Rev Neurother. 2009;9:87–98. doi: 10.1586/14737175.9.1.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa E, Guidotti A. Benzodiazepines on trial: a research strategy for their rehabilitation. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 1996;17:192–200. doi: 10.1016/0165-6147(96)10015-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa E, Guidotti A. Diazepam binding inhibitor (DBI): a peptide with multiple biological actions. Life Science. 1991;49:325–344. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(91)90440-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson JR. Use of benzodiazepines in social anxiety disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, and posttraumatic stress disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65:29–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Aquila PS, Canu S, Sardella M, Spanu C, Serra G, Franconi F. Dopamine is involved in the antidepressant-like effect of allopregnanolone in the forced swimming test in female rats. Behav Pharmacol. 2010;21:21–8. doi: 10.1097/FBP.0b013e32833470a7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deo GS, Dandekar MP, Upadhya MA, Kokare DM, Subhedar NK. Neuropeptide Y Y1 receptors in the central nucleus of amygdala mediate the anxiolytic-like effect of allopregnanolone in mice: Behavioral and immunocytochemical evidences. Brain Res. 2010;1318:77–86. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2009.12.088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong E, Matsumoto K, Uzunova V, Sugaya I, Costa E, Guidotti A. Brain 5α-dihydroprogesterone and allopregnanolone synthesis in a mouse model of protracted social isolation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:2849–2854. doi: 10.1073/pnas.051628598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong E, Guidotti A, Grayson DR, Costa E. Histone hyperacetylation induces demethylation of reelin and 67-kDa glutamic acid decarboxylase promoters. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:4676–4681. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0700529104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engin E, Treit D. The anxiolytic-like effects of allopregnanolone vary as a function of intracerebral microinfusion site: the amygdala, medial prefrontal cortex, or hippocampus. Behav Pharmacol. 2007;18:461–70. doi: 10.1097/FBP.0b013e3282d28f6f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eser D, Schüle C, Baghai TC, Romeo E, Rupprecht R. Neuroactive steroids in depression and anxiety disorders: clinical studies. Neuroendocrinology. 2006;84:244–54. doi: 10.1159/000097879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Essman EJ, Valzelli L. Brain benzodiazepine receptor changes in the isolated aggressive mouse. Pharmacol Res Commun. 1981;13:665–71. doi: 10.1016/s0031-6989(81)80054-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forbes D, Parslow R, Creamer M, Allen N, McHugh T, Hopwood M. Mechanisms of anger and treatment outcome in combat veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder. J Trauma Stress. 2008;21:142–9. doi: 10.1002/jts.20315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frye CA, Rhodes ME. Infusions of 5alpha-pregnan-3alpha-ol-20-one (3alpha,5alpha-THP) to the ventral tegmental area, but not the substantia nigra, enhance exploratory, anti-anxiety, social and sexual behaviours and concomitantly increase 3alpha,5alpha-THP concentrations in the hippocampus, diencephalon and cortex of ovariectomised oestrogen-primed rats. J Neuroendocrinol. 2006;18:960–75. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2826.2006.01494.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frye CA, Paris JJ, Rhodes ME. Increasing 3alpha,5alpha-THP following inhibition of neurosteroid biosynthesis in the ventral tegmental area reinstates anti-anxiety, social, and sexual behavior of naturally receptive rats. Reproduction. 2009;137:119–28. doi: 10.1530/REP-08-0250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garattini S, Giacalone E, Valzelli L. Isolation, aggressiveness and brain 5-hydroxytryptamine turnover. J Pharm Pharmacol. 1967;19:338–9. doi: 10.1111/j.2042-7158.1967.tb08099.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gee KW, Bolger MB, Brinton RE, Coirini H, McEwen BS. Steroid modulation of the chloride ionophore in rat brain: structure-activity requirements, regional dependence and mechanism of action. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1988;246:803–812. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelpin E, Bonne O, Peri T, Brandes D, Shalev AY. Treatment of recent trauma survivors with benzodiazepines: a prospective study. J Clin Psychiatry. 1996;57:390–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geuze E, van Berckel BN, Lammertsma AA, Boellaard R, de Kloet CS, Vermetten E, Westenberg HG. Reduced GABAA benzodiazepine receptor binding in veterans with post-traumatic stress disorder. Molecular Psychiatry. 2008;13:74–83. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4002054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffin LD, Mellon SH. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors directly alter activity of neurosteroidogenic enzymes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:13512–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.23.13512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grillon C, Morgan CA. Fear-potentiated startle conditioning to explicit and contextual cues in Gulf War veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder. J Abnorm Psycho. 1999;108:134–42. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.108.1.134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guidotti A, Dong E, Kundakovic M, Satta R, Grayson DR, Costa E. Characterization of the action of antipsychotic subtypes on valproate-induced chromatin remodeling. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2009;30:55–60. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2008.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guidotti A, Costa E. Can the antidysphoric and anxiolytic profiles of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors be related to their ability to increase brain 3 alpha, 5alpha-tetrahydroprogesterone (allopregnanolone) availability? Biol Psychiatry. 1998;44:865–873. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(98)00070-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guidotti A, Dong E, Matsumoto K, Pinna G, Rasmusson AM, Costa E. The socially-isolated mouse: a model to study the putative role of allopregnanolone and 5α-dihydroprogesterone in psychiatric disorders. Brain Res Rev. 2001;37:110–115. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(01)00129-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirschdeld RMA. History and evolution of the monoamine hypothesis of depression. J Clin Psychiatry. 2000;61:4–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosie AM, Wilkins ME, da Silva HM, Smart TG. Endogenous neurosteroids regulate GABAA receptors through two discrete transmembrane sites. Nature. 2006;444:486–9. doi: 10.1038/nature05324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jain NS, Hirani K, Chopde CT. Reversal of caffeine-induced anxiety by neurosteroid 3-alpha-hydroxy-5-alpha-pregnane-20-one in rats. Neuropharmacology. 2005;48:627–38. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2004.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kita, Furukawa Involvement of neurosteroids in the anxiolytic-like effects of AC-5216 in mice. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2008;89:171–8. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2007.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kundakovic M, Chen Y, Costa E, Grayson DR. DNA methyltransferase inhibitors coordinately induce expression of the human reelin and glutamic acid decarboxylase 67 genes. Mol Pharmacol. 2007;71:644–653. doi: 10.1124/mol.106.030635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambert JJ, Belelli D, Peden DR, Vardy AW, Peters JA. Neurosteroid modulation of GABAA receptors. Prog Neurobiol. 2003;71:67–80. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2003.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambert JJ, Cooper MA, Simmons RD, Weir CJ, Belelli D. Neurosteroids: endogenous allosteric modulators of GABAA receptors. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2009;34(Suppl 1):S48–58. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2009.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lonsdale, Burnham The anticonvulsant effects of allopregnanolone against amygdala-kindled seizures in female rats. Neurosci Lett. 2007;411:147–51. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2006.10.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longone P, Rupprecht R, Manieri GA, Bernardi G, Romeo E, Pasini A. The complex roles of neurosteroids in depression and anxiety disorders. Neurochem Int. 2008;52:596–601. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2007.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maguire J, Mody I. Steroid hormone fluctuations and GABAA R plasticity. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2009;34(Suppl 1):S84–90. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2009.06.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Majewska MD. Neurosteroids: endogenous bimodal modulators of the GABAA receptor. Mechanism of action and physiological significance. Prog Neurobiol. 1992;38:379–395. doi: 10.1016/0301-0082(92)90025-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mares P, Mikulecká A, Haugvicová R, Kasal A. Anticonvulsant action of allopregnanolone in immature rats. Epilepsy Res. 2006;70:110–7. doi: 10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2006.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin-Garcia E, Pallares M. The intrahippocampal administration of the neurosteroid allopregnanolone blocks the audiogenic seizures induced by nicotine. Brain Res. 2005;1062:144–50. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2005.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Arguelles DB, Papadopoulos V. Epigenetic regulation of the expression of genes involved in steroid hormone biosynthesis and action. Steroids. 2010;75:467–76. doi: 10.1016/j.steroids.2010.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marx CE, Keefe RS, Buchanan RW, Hamer RM, Kilts JD, Bradford DW, et al. Proof-of-concept trial with the neurosteroid pregnenolone targeting cognitive and negative symptoms in schizophrenia. Neuropsycopharmacology. 2009;34:1885–903. doi: 10.1038/npp.2009.26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto K, Nomura H, Murakami Y, Taki K, Takahata H, Watanabe H. Long-term social isolation enhances picrotoxin seizure susceptibility in mice: up-regulatory role of endogenous brain allopregnanolone in GABAergic systems. Pharm Biochem Behav. 2003;75:831–835. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(03)00169-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto K, Puia G, Dong E, Pinna G. GABAA receptor neurotransmission dysfunction in a mouse model of social isolation-induced stress: possible insights into a non-serotonergic mechanism of action of SSRIs in mood and anxiety disorders. Stress. 2007;10:3–12. doi: 10.1080/10253890701200997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto K, Uzunova V, Pinna G, Taki K, Uzunov DP, Watanabe H, Mienvielle J-M, Guidotti A, Costa E. Permissive role of brain allopregnanolone content in the regulation of pentobarbital-induced righting reflex loss. Neuropharmacology. 1999;38:955–963. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(99)00018-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEwen BS, Chattarji S, Diamond DM, Jay TM, Reagan LP, Svenningsson P, Fuchs E. The neurobiological properties of tianeptine (Stablon): from monoamine hypothesis to glutamatergic modulation. Mol Psychiatry. 2010;15:237–49. doi: 10.1038/mp.2009.80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mennini T, Mocaer E, Garattini S. Tianeptine, a selective enhancer of serotonin uptake in rat brain. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 1987;336:478–482. doi: 10.1007/BF00169302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mongeau R, Blier P, de Montigny C. The serotonergic and noradrenergic systems of the hippocampus: their interactions and the effects of antidepressant treatments. Brain Res Rev. 1997;23:145–195. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(96)00017-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nappi RE, Petraglia F, Luisi S, Polatti F, Farina C, Genazzani AR. Serum allopregnanolone in women with postpartum “blues”. Obstet Gynecol. 2001;97:77–80. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(00)01112-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson M, Pinna G. S-norfluoxetine infused into the basolateral amygdala increases allopregnanolone levels and reduces aggression in socially isolated mice. Neuropharmacology. 2010 doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2010.10.011. Submitted. **** Not sure how we deal with this. Just ‘Submitted for publication’ without the journal name??? *** - Ed. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nestler EJ, Barrot M, DiLeone RJ, Eisch AJ, Gold SJ. Neurobiology of depression. Neuron. 2002;34:13–25. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00653-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nin MS, Salles FB, Azeredo LA, Frazon AP, Gomez R, Barros HM. Antidepressant effect and changes of GABAA receptor gamma2 subunit mRNA after hippocampal administration of allopregnanolone in rats. J Psychopharmacol. 2008;22:477–85. doi: 10.1177/0269881107081525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillipps GH. Structure activity relationships in steroidal anaesthetics. J Steroid Biochem. 1975;6:607–613. doi: 10.1016/0022-4731(75)90041-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pibiri F, Nelson M, Guidotti A, Costa E, Pinna G. Decreased allopregnanolone content during social isolation enhances contextual fear: a model relevant for posttraumatic stress disorder. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:5567–5572. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0801853105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinault D. The thalamic reticular nucleus: structure, function and concept. Brain Res Rev. 2004;46:1–31. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2004.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinna G, Uzunova V, Matsumoto K, Puia G, Mienville J-M, Costa E, Guidotti A. Brain allopregnanolone regulates the potency of the GABAA receptor agonist muscimol. Neuropharmacology. 2000;39:440–448. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(99)00149-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinna G, Dong E, Matsumoto K, Costa E, Guidotti A. In socially isolated mice, the reversal of brain allopregnanolone down-regulation mediates the anti-aggressive action of fluoxetine. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003a;100:2035–2040. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0337642100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinna G, Liskevych U, Doueiri MS, Costa E, Guidotti A. Antidepressants in doses that increase neurosteroid biosynthesis but fail to inhibit 5-HT reuptake reduce expression of aggression in socially isolated (SI) mice. Program No. 664.2. 2003 Neuroscience Meeting Planner; 2003.New Orleans, LA: Society for Neuroscience; 2003b. [Google Scholar]

- Pinna G, Costa E, Guidotti A. Fluoxetine and norfluoxetine stereospecifically facilitate pentobarbital sedation by increasing neurosteroids. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:6222–6225. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0401479101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinna G, Costa E, Guidotti A. Fluoxetine and norfluoxetine stereospecifically and selectively increase brain neurosteroid content at doses that are inactive on 5-HT reuptake. Psychopharmacology. 2006a;186:362–372. doi: 10.1007/s00213-005-0213-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinna G, Agis-Balboa RC, Zhubi A, Matsumoto K, Grayson DR, Costa E, Guidotti A. Imidazenil and diazepam increase locomotor activity in mice exposed to protracted social isolation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006b;103:4275–4280. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0600329103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinna G, Agis-Balboa R, Pibiri F, Nelson M, Guidotti A, Costa E. Neurosteroid biosynthesis regulates sexually dimorphic fear and aggressive behavior in mice. Neurochemical Research. 2008;33:1990–2007. doi: 10.1007/s11064-008-9718-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinna G, Costa E, Guidotti A. SSRIs act as selective brain steroidogenic stimulants (SBSSs) at low doses that are inactive on 5-HT reuptake. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2009;9:24–30. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2008.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pisu MG, Serra M. Neurosteroids and neuroactive drugs in mental disorders. Life Sci. 2004;74:3181–3197. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2003.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potts BD, Parli J. Analysis of the enantiomers of fluoxetine and norfluoxetine in plasma and tissue using chiral derivatization and normal-phase liquid chromatography. J Liquid Chromatography. 1992;15:665–681. [Google Scholar]

- Puia G, Santi MR, Vicini S, Pritchett DB, Purdy RH, Paul SM, Seeburg PH, Costa E. Neurosteroids act on recombinant human GABAA receptors. Neuron. 1990;4:759–765. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(90)90202-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puia G, Vicini S, Seeburg PH, Costa E. Influence of recombinant gamma-aminobutyric acid—a receptor subunit composition on the action of allosteric modulators of gammaaminobutyricacid-gated Cl-currents. Mol Pharmacol. 1991;39:691–696. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puia G, Mienville J-M, Matsumoto K, Takahata H, Watanabe H, Costa E, Guidotti A. On theputative physiological role of allopregnanolone on GABAA receptor function. Neuropharmacology. 2003;44:49–55. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(02)00341-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rapkin AJ, Morgan M, Goldman L, Brann DW, Simone D, Mahesh VB. Progesterone metabolite allopregnanolone in women with presmenstrual syndrome. Obstet Gynecol. 1997;90:709–14. doi: 10.1016/S0029-7844(97)00417-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasmusson AM, Pinna G, Paliwal P, Weisman D, Gottschalk C, Charney D, et al. Decreased cerebrospinal fluid allopregnanolone levels in women with posttraumatic stress disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2006;60:704–13. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.03.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rauch SL, Shin LM, Phelps EA. Neurocircuitry models of posttraumatic stress disorder and extinction: human neuroimaging research--past, present, and future. Biol Psychiatry. 2006;60:376–82. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddy DS, Rogawski MA. Chronic treatment with the neuroactive steroid ganaloxone in the rat induces anticonvulsant tolerance to diazepam but not to itself. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2000;295:1241–1248. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddy DS, Woodward R. Ganaxolone: a prospective overview. Drugs Future. 2004;29:227–242. [Google Scholar]

- Rodgers RJ, Johnson NJ. Behaviorally selective effects of neuroactive steroids on plus-maze anxiety in mice. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1998;59:221–32. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(97)00339-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-Landa JF, Contreras CM, García-Ríos RI. Allopregnanolone microinjected into the lateral septum or dorsal hippocampus reduces immobility in the forced swim test: participation of the GABAA receptor. Behav Pharmacol. 2009;20:614–622. doi: 10.1097/FBP.0b013e328331b9f2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romeo E, Ströhle A, Spalletta G, di Michele F, Hermann B, Holsboer F, Pasini A, Rupprecht R. Effects of antidepressant treatment on neuroactive steroids in major depression. Am J Psychiatry. 1998;155:910–3. doi: 10.1176/ajp.155.7.910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romeo E, Auta J, Kozikowski AP, Ma D, Papadopoulos V, Puia G, Costa E, Guidotti A. 2-Aryl-3-indoleacetamides (FGIN-1): a new class of potent and specific ligands for the mitochondrial DBI receptor (MDR) J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1992;262:971–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rupprecht R, Holsboer F. Neuroactive steroids: mechanisms of action and neuropsychopharmacological perspectives. Trends Neurosci. 1999;22:410–416. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(99)01399-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Safe S, Kim K. Nuclear receptor-mediated transactivation through interaction with Sp proteins. Prog Nucleic Acid Res Mol Biol. 2004;77:1–36. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6603(04)77001-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santarelli L, Saxe M, Gross C, Surget A, Battaglia F, Dulawa S, Weisstaub N, Lee J, Duman R, Arancio O, Belzung C, Hen R. Requirement of hippocampal neurogenesis for the behavioral effects of antidepressants. Science. 2003;301:805–9. doi: 10.1126/science.1083328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schildkraut JJ. The catecholamine hypothesis of affective disorders: a review of the supporting evidence. Am J Psychiatry. 1965;122:509–521. doi: 10.1176/ajp.122.5.509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith SS, Gong QH, Hsu FC, Markowitz RS, ffrench-Mullen JMX, Li X. GABAA receptor α4-subunit supression prevents withdrawal properties of an endogenous steroid. Nature. 1998;392:926–930. doi: 10.1038/31948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoffel-Wagner B. Neurosteroid metabolism in the human brain. European Journal of Endocrinology. 2001;145:669–679. doi: 10.1530/eje.0.1450669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ströhle A, Romeo E, di Michele F, Pasini A, Yassouridis A, Holsboer F, Rupprecht R. GABAA receptor-modulationg neuroactive steroid composition in patients with panic disorder before and during paroxetine treatment. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159:145–7. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.1.145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tallarida RJ, Murray RB. Manual of Pharmacologic Calculations with Computer Programs. 2. New York: Springer; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Tremolizzo L, Doueiri MS, Dong E, Grayson DR, Davis J, Pinna G, Tueting P, Rodriguez-Menendez V, Costa E, Guidotti A. Valproate corrects the schizophrenia-like epigenetic behavioral modifications induced by methionine in mice. Biol Psychiatry. 2005;57:500–509. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.11.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tueting P, Pinna G, Costa E. Homozygous and heterozygous reeler mouse mutants. In: Fatemi SH, editor. Reelin Glycoprotein: Structure, Biology and Roles in Health Disease. Springer; 2008. pp. 291–309. [Google Scholar]

- Trauger JW, Jiang A, Stearns BA, LoGrasso PV. Kinetics of allopregnanolone formation catalyzed by human 3 alpha hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase TypeIII (AKR1C2) Biochemistry. 2002;41:13451–13459. doi: 10.1021/bi026109w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsankova N, Renthal W, Kumar A, Nestler EJ. Epigenetic regulation in psychiatric disorders. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2007;8:355–367. doi: 10.1038/nrn2132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uzunov DP, Cooper TB, Costa E, Guidotti A. Fluoxetine elicited changes in brain neurosteroid content measured by negative ion mass fragmentography. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:12599–12604. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.22.12599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uzunova V, Sheline Y, Davis JM, Rasmusson A, Uzunov DP, Costa E, Guidotti A. Increase in the cerebrospinal fluid content of neurosteroids in patients with unipolar major depression who are receiving fluoxetine or fluvoxamine. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:3239–44. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.6.3239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uzunova V, Ceci M, Kohler C, Uzunov DP, Wrynn AS. Region-specific dysregulation of allopregnanolone brain content in the olfactory bulbectomized rat model of depression. Brain Res. 2003;976:1–8. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(03)02577-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uzunova V, Wrynn AS, Kinnunen A, Ceci M, Kohler C, Uzunov DP. Chronic antidepressants reverse cerebrocortical allopregnanolone decline in the olfactory-bulbectomized rat. Eur J Pharmacol. 2004;486:31–4. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2003.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uzunova V, Sampson L, Uzunov DP. Relevance of endogenous 3α-reduced neurosteroids to depression and antidepressant action. Psychopharmacology. 2006;186:351–361. doi: 10.1007/s00213-005-0201-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valzelli L. Psychopharmacology of aggression: an overview. Int Pharmacopsychiatry. 1981;16:39–48. doi: 10.1159/000468473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vicini S. Pharmacologic significance of the structural heterogeneity of the GABAA receptor-chloride ion channel complex. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1991;4:9–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viola J, Ditzler T, Batzer W, Harazin J, Adams D, Lettich L, Berigan T. Pharmacological management of post-traumatic stress disorder: clinical summary of a five-year retrospective study, 1990–1995. Mil Med. 1997;162:616–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wieland S, Lan NC, Mirasedeghi S, Gee KW. Anxiolytic activity of the progesterone metabolite 5 alpha-pregnan-3 alpha-o1–20-one. Brain Res. 1991;565:263–8. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(91)91658-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong DT, Bymaster FP, Reid LR, Mayle DA, Krushinski JH, Robertson DW. Norfluoxetine enantiomers as inhibitors of serotonin uptake in rat brain. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1993;8:337–344. doi: 10.1038/npp.1993.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]