Abstract

Background

The authors surveyed U.S. medical students to learn their perceptions of the adequacy of women's health and sex/gender-specific teaching and of their preparedness to care for female patients.

Methods

Between September 2004 and June 2005, third and fourth year students at the 125 allopathic medical schools received an online survey conducted by the American Medical Women's Association (AMWA). Students rated the extent to which 44 topics were included in curricula from 1 to 4 (1 = no coverage, 4 = in-depth coverage) and their preparedness to perform 27 clinical skills (1 = no preparation, 4 = thorough preparation).

Results

From 101 of the 125 schools, 1267 students responded (mean number of respondents/school = 13, SD 12). The mean curriculum rating (2.53, SD 0.52) indicated brief to moderate coverage of topics. The mean preparedness rating was higher (3.09, SD 0.44), indicating moderate preparedness. In a regression model, female student sex and site of an AMWA chapter were associated with lower mean combined curriculum and preparedness ratings (female 2.76, male 3.01, p < 0.001; AMWA 2.77, non-AMWA 2.89, p < 0.001), whereas other school characteristics (female dean, federally funded women's health program, and proportion of tenured women faculty) had no association.

Conclusions

Although medical students reported that they were moderately prepared to care for women, their low rating of curriculum coverage of women's health and sex/gender-specific topics suggests important gaps in teaching. Lower ratings by female students and by those at AMWA schools may reflect differences in students' knowledge, educational expectations, or perceptions about the importance of topics.

Introduction

In response to concerns that physicians were not adequately trained to provide comprehensive care to women, Congress requested in 1993 that the Office of Research on Women's Health at the National Institutes of Health (NIH), the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA), and the Public Health Service Office on Women's Health collaborate on a study of medical school curricula to determine the extent to which women's health issues were addressed. To obtain this information, the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) conducted a two-part survey of medical school administrators in 1994 and 1995. The findings, published in 1996, showed wide variation among schools in their approach to women's health and the degree to which women's health topics and other educational experiences were included in curricula.1

At the time of the survey in 1994–1995, almost all schools taught core topics on sexual and reproductive function, medical interviewing and examination skills, and diagnostic tests specific to women; fewer incorporated sex/gender-specific information on leading causes of death and disability in women or on chronic medical disorders that disproportionately affect women.1 Only a small proportion of schools (14%) reported having implemented a women's health curriculum, more than one fourth (28%) offered a clinical rotation in women's health that was separate from a traditional obstetrics/gynecology clerkship, and 10% had an office or program responsible for integrating women's health and sex/gender-specific information into the curriculum.1

Subsequent surveys of administrators and a review of a centralized medical school database concluded that progress in women's health curricular activities in U.S. medical schools has been uneven.2–6 The proportion of schools with an office or program with women's health curriculum oversight increased from 10% in 1994–1995 to 33% in 20007; however, only 30% of schools in 2004 listed information in their curricula on sex/gender-specific topics.2 This is surprising given the establishment in 1996 of federally funded women's health programs at selected academic medical centers that were required to develop women's health curricular models8 and the work of other government agencies and nongovernmental organizations in providing the knowledge base and tools necessary to initiate change.9–14

Because student opinions were not sought in previous studies of women's health curricular activities at U.S. medical schools,1–6 we designed the present study to (1) seek students' perceptions of the extent to which women's health and sex/gender-specific information are integrated into curricula and of their preparedness to provide care to female patients, (2) assess progress made by schools in the integration of that content, and (3) identify school factors that are associated with students' perceptions.

Materials and Methods

Participants

Between September 2004 and June 2005, we surveyed third and fourth year medical students at U.S. allopathic medical schools using an online survey conducted by the American Medical Women's Association (AMWA), an organization of women physicians and medical students whose goal is to advance women's health issues and women in medicine. AMWA has active student chapters at 74 of the 125 U.S. medical schools, led by national, regional, and local chapter student representatives.

AMWA e-mailed the survey link to regional and local student AMWA representatives at schools with AMWA chapters and directly to student AMWA members with e-mail addresses. The e-mail invited the approximately 1400 third and fourth year AMWA students to participate in the survey and encouraged them to send the survey link to non-AMWA students, particularly male colleagues. The AMWA electronic newsletter sent monthly reminders containing the survey link. Information about the survey was also e-mailed to other national student organizations and to all student affairs deans at U.S. medical schools. We invited deans to distribute the AMWA survey link to third and fourth year students at their institutions; deans received a follow-up e-mail or a phone call or both if no students from their school responded within 2 weeks of the first e-mail. Our goal was to reach as many students as possible; however, we did not have a mechanism to determine how many third and fourth year medical students at the time of the survey actually received the survey link or by what route and were thus not able to calculate an accurate response rate.

Survey instrument

We designed the survey instrument in collaboration with the government offices named in the initial Congressional directive and with AMWA. It consisted of 101 items derived from the 1994–1995 AAMC survey1 and from updated information on women's health competencies for medical students published by the Association of Professors of Gynecology and Obstetrics.13,14 Thirty-eight students at 10 schools responded to a preliminary survey sent in May and June 2004; we made minor changes to the survey instrument based on their comments.

The survey sought data about students' perceptions of the extent to which certain topics were included in their curriculum (curriculum assessment) and students' self-reported preparedness to perform a range of clinical skills (preparedness). Additional information about clinical training and the learning environment at schools was obtained. Students accessed the survey online through a secure link. The survey took approximately 20 minutes to complete and was anonymous. The survey was designed to recognize respondents' computers. To guarantee anonymity, however, we did not collect other identifying information, and it is possible that a student could have used different computers to complete more than one survey.

Data analysis

The curriculum assessment section of the survey included 44 items that were divided into six categories related to topics in the basic sciences, gender identification and interpersonal violence, the influence of sex and gender on mental health, women's sexual and reproductive function, women's preventive health, and the influence of sex and gender on common medical problems. Students rated the extent to which a topic was either integrated into or covered in the curriculum using an ordinal scale with four responses. Responses were assigned the following values: not included/not covered at all = 1, restricted to a few topics/brief coverage = 2, integrated into many topics/moderate coverage = 3, and integrated throughout/in-depth coverage = 4. (Not sure responses were considered missing and were excluded from analysis; the mean proportion of missing responses was 2.7%, SD 2.2%.) In the preparedness section, 27 items were divided into two categories related to students' self-reported preparedness to conduct/perform selected clinical skills and students' self-reported preparedness to educate/counsel female patients on certain topics. Students rated their preparedness using a similar scale: not prepared at all = 1, minimally prepared = 2, moderately prepared = 3, and thoroughly prepared = 4. (Not sure responses were excluded from analysis; the mean proportion of missing responses was 0.6%, SD 0.9%.)

We calculated the mean rating for the six categories in the curriculum assessment section (curriculum rating), the two categories in the preparedness section (preparedness rating), and the mean of the curriculum and preparedness ratings (combined curriculum and preparedness rating). To identify potential factors that may influence ratings, we evaluated selected school characteristics using analysis of variance (ANOVA) to compare differences between mean combined ratings. SAS version 9.1 statistical software (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC) was used for all analyses. Respondents' school characteristics included the presence of a student AMWA chapter, geographic region (northeastern, southern, central or western United States), public or private status, designation as a federally funded National Center of Excellence (CoE) in Women's Health, site of an NIH-funded Building Interdisciplinary Research Careers in Women's Health (BIRCWH) Career Development Program, and presence of a female medical school dean. The proportion of women on the tenured faculty was examined in a regression model for association with the mean combined rating. We then examined the relationship between these characteristics and mean combined ratings by considering all features in a stepwise regression model using a p value of 0.15 for inclusion and retention.

To examine variability in ratings between schools, we calculated the mean combined rating for each school with more than 10 student respondents. We analyzed students' responses to open-ended questions by identifying common themes and selecting student quotes that best illustrated those themes.

Results

Respondents

A total of 1267 students (696 third year and 571 fourth year) from 101 of the 125 U.S. medical schools (81%) responded to the survey. (Based on LCME data, we estimated that the number of third and fourth year students at the 101 schools was about 27,000, of whom 49% were women.15) The number of respondents from each of the 101 schools ranged from 1 to 61, with a mean of 13 (SD 12). Seventy-one percent of students were from schools with an AMWA chapter; 78% of respondents at AMWA schools were women compared with 79% at non-AMWA schools. There was greater participation at schools with an AMWA chapter (mean number of respondents at AMWA schools = 14, SD 12; non-AMWA schools, mean = 11, SD 13).

Curriculum assessment and preparedness ratings

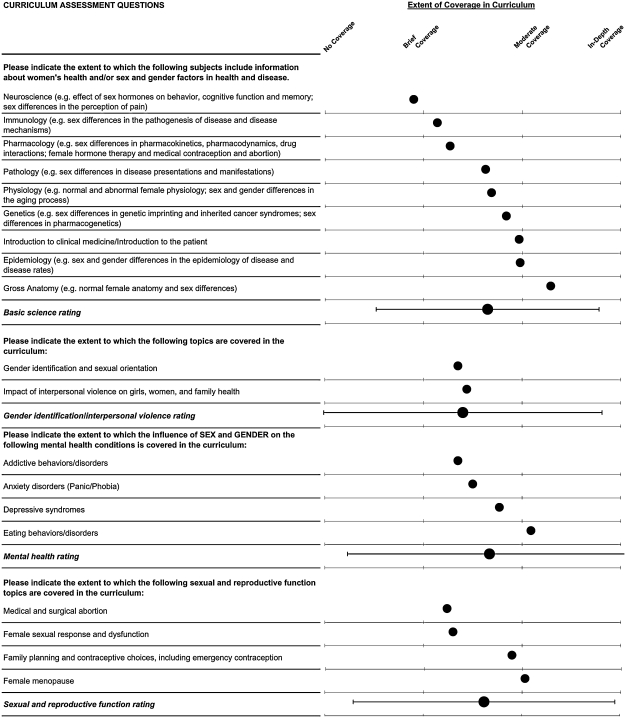

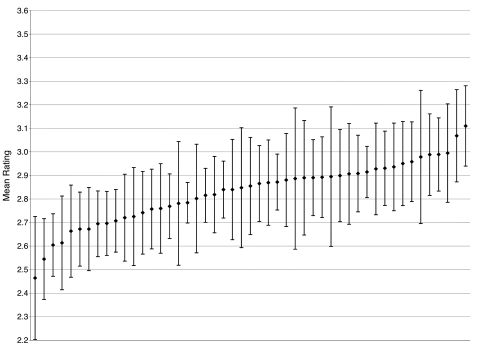

Figure 1 shows mean ratings for each curriculum assessment item and category and the mean curriculum rating. The mean curriculum rating of 2.53 (SD 0.52) indicated brief to moderate coverage/integration of topics. Mean ratings for the six curriculum categories were, in descending order: sex/gender information on mental health disorders (2.67, SD 0.74) and basic science topics (2.65, SD 0.58); sexual and reproductive function (2.62, SD 0.68); sex/gender information on preventive health topics (2.49, SD 0.63); gender identification and interpersonal violence (2.40, SD 0.72); and sex/gender information on common medical conditions (2.38, SD 0.64). Only 6 of the 44 individual curriculum topics listed in the survey received mean ratings >3, indicating moderate to in-depth coverage (risk prevention and screening for cardiovascular disease, osteoporosis and cancer in women; and sex/gender information in anatomy, depressive syndromes, and autoimmune disorders). Five topics received mean ratings <2, indicating brief or no inclusion/coverage (women's sexual practices, and sex/gender information in the neurosciences, occupational health, sports injuries, and dementia states).

FIG. 1.

Mean response ratings to curriculum assessment questions (n = 1267). The dots represent the mean rating. The horizontal bars represent 2 SD around the average rating.

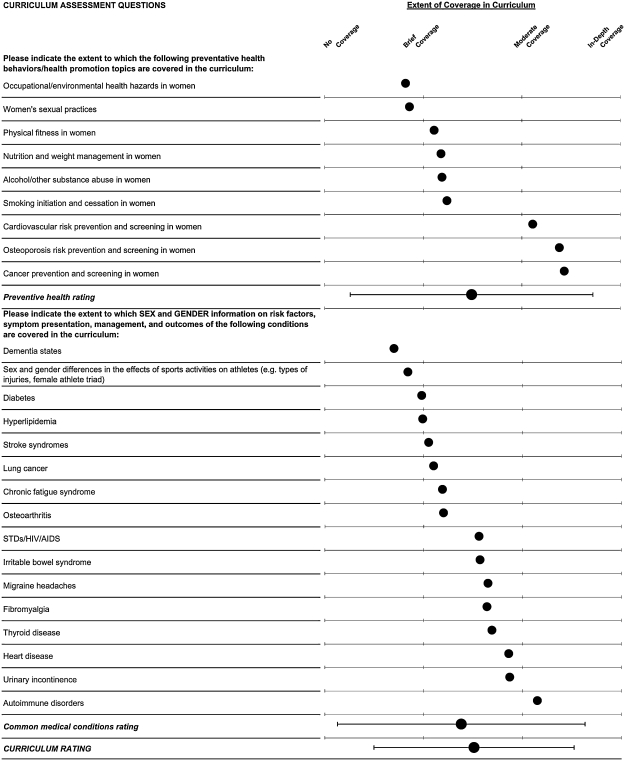

Figure 2 shows mean ratings for each preparedness item and category and the combined curriculum and preparedness rating. The mean preparedness rating (3.09, SD 0.44) indicated that students perceived that they were moderately prepared to perform the range of skills listed in the survey. Although the two preparedness categories had similar ratings (conduct/perform selected skills, 3.05, SD 0.46; educate/counsel patients on certain topics, 3.12, SD 0.48), 17 of the 27 preparedness items received ratings >3, indicating moderate to thorough preparedness. These included basic reproductive health-related interviewing; examination and counseling skills; screening for depression, breast and colon cancer; counseling about substance use; assessing risks for cardiovascular disease and osteoporosis in women; and managing diabetes. Only one topic, follow a rape protocol, received a rating <2.

FIG. 2.

Mean response ratings to preparedness questions and mean combined curriculum and preparedness rating (n = 1267). The dots represent the mean rating. The horizontal bars represent 2 SD around the average rating.

The curriculum assessment and preparedness sections of the survey were designed to explore different domains of students' experience and were not comparable (e.g., most basic science topics in the curriculum assessment section had no preparedness counterpart). However, some curriculum topics were closely related to the clinical skills listed in the preparedness section (e.g., the topic, female menopause, was related to the skill, management of menopause). Topics that received the lowest curriculum ratings (sex/gender-specific information on certain medical conditions, and medical and surgical abortion) had either no related preparedness question or a corresponding low preparedness rating. With some exceptions, topics that received high curriculum ratings also received the highest preparedness ratings (e.g., educate/counsel women on cardiovascular disease risks and prevention). The topics, female sexual response and function and addictive behaviors/disorders, exhibited the greatest disparity between curriculum ratings (low) and related preparedness ratings (high).

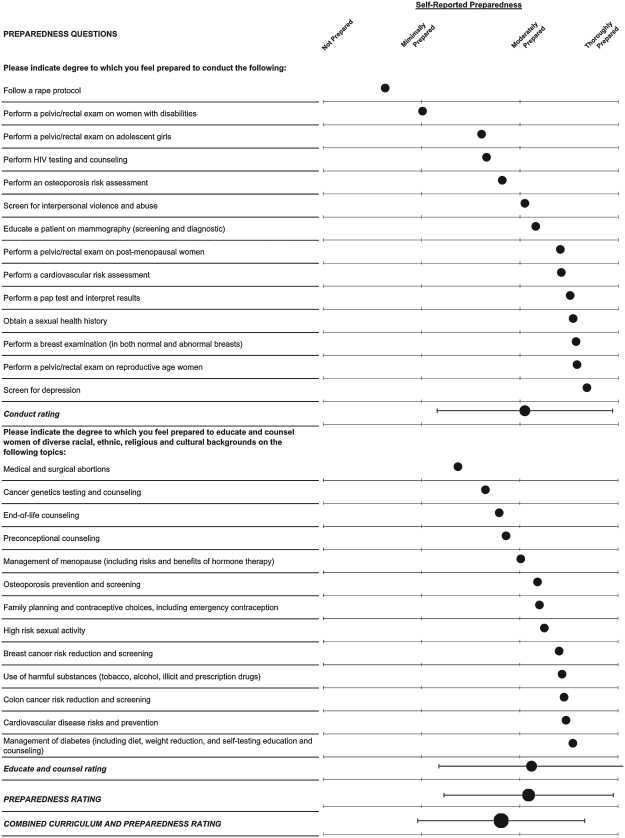

Figure 3 shows the mean curriculum and preparedness ratings by class year and gender. Mean curriculum ratings were statistically significantly lower in female compared with male students. Differences between female and male mean preparedness ratings were small and were statistically significant only in class year 3.

FIG. 3.

Mean curriculum assessment and preparedness ratings by class year and gender (n = 1267). The vertical bars represent 95% confidence intervals around the mean rating.

Association between respondents' school characteristics and ratings

When we examined the bivariate association between respondents' sex and school characteristics and the combined curriculum and preparedness rating, female student sex, the presence of an AMWA chapter, and a BIRCWH program were statistically significantly associated with lower mean ratings (Table 1). When we entered these characteristics into a regression model, central U.S. geographic region was significantly associated with higher ratings, and female sex and an AMWA chapter were associated with lower ratings (Table 1). Except for female sex, however, actual quantitative differences in ratings were very small. Although the presence of a BIRCWH program met the significance level of 0.15 for entry into the regression model, it was not statistically significantly associated with student ratings. No other school characteristics, including the proportion of tenured women or the presence of a female dean or CoE, met entry criteria of the model.

Table 1.

Mean Combined Curriculum and Preparedness Rating According to Respondent Characteristics (n = 1267)

| |

Mean Combined Curriculum and Preparedness Rating (No. of respondents) |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Characteristic present | Characteristic absent | p value |

| Female | 2.76 (995) | 3.01 (272) | <0.0001 |

| AMWA chaptera | 2.77 (898) | 2.89 (369) | <0.0001 |

| Region | |||

| Northeastern | 2.78 (312) | 2.82 (995) | 0.18 |

| Southern | 2.80 (375) | 2.81 (892) | 0.74 |

| Central | 2.84 (407) | 2.80 (860) | 0.07 |

| Western | 2.80 (173) | 2.81 (1094) | 0.72 |

| Private university | 2.82 (410) | 2.81 (857) | 0.48 |

| CoEb | 2.78 (228) | 2.82 (1039) | 0.28 |

| BIRCWH Programc | 2.75 (251) | 2.83 (1016) | 0.01 |

| Female dean | 2.76 (101) | 2.82 (1166) | 0.18 |

| % Tenured womend | −0.003 | 0.77 | |

| Regression modele | Female respondent (−0.23) | <0.0001 | |

| AMWA chapter (−0.12) | <0.0001 | ||

| Central region (+0.07) | 0.01 | ||

| BIRCWH program (−0.04) | 0.15 | ||

American Medical Women's Association student chapter.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services funded National Center of Excellence in Women's Health.

National Institutes of Health, Office of Research on Women's Health-sponsored Building Interdisciplinary Research Careers in Women's Health (BIRCWH) program.

Estimated change from linear regression for +1 SD change in tenured female faculty.

Stepwise linear regression model selected with entry and retention p value set at 0.15. Predicted changes in mean combined rating when characteristic is present are shown in parentheses after selected characteristics.

We then compared the distribution of school characteristics between schools represented in the survey compared with those that were not. The only significant difference was a higher proportion of schools with an AMWA chapter in schools represented in the survey (Table 2).

Table 2.

Comparison of Schools Represented in Survey with Those Not Represented (n = 125)

| Characteristic | Schools represented (n = 101) No. (%) | Schools not represented (n = 24) No. (%) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| AMWA chaptera | 66 (65) | 8 (33) | 0.004 |

| Region | |||

| Northeastern | 27 (27) | 8 (33) | 0.52 |

| Southern | 32 (32) | 11 (46) | 0.19 |

| Central | 28 (28) | 3 (13) | 0.12 |

| Western | 14 (14) | 2 (8) | 0.47 |

| Private university | 39 (39) | 11 (46) | 0.52 |

| CoEb | 17 (17) | 4 (17) | 0.98 |

| BIRCWH Programc | 20 (20) | 2 (8) | 0.18 |

| Female dean | 9 (9) | 4 (17) | 0.26 |

| % Tenured women (mean ± SD)d | 0.15 ± 0.09 | 0.14 ± 0.10 | 0.58 |

American Medical Women's Association student chapter.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services-funded National Center of Excellence in Women's Health.

National Institutes of Health, Office of Research on Women's Health-sponsored Building Interdisciplinary Research Careers in Women's Health (BIRCWH) program.

Estimated change from linear regression for +1 SD change in tenured female faculty (0.08) or proportion female student responses (0.14).

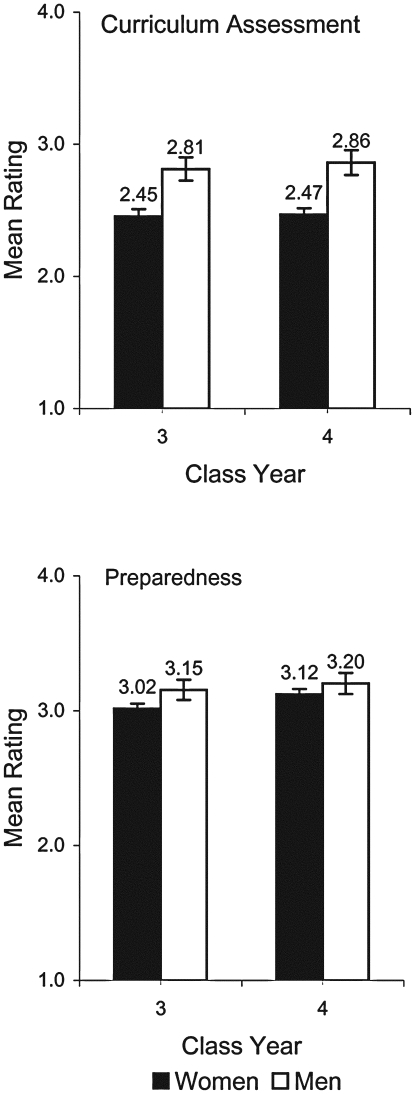

We also calculated the mean combined curriculum and preparedness rating for the 47 schools with more than 10 student respondents (Fig. 4). Schools' mean combined ratings ranged from 2.46 (SE 0.13) to 3.11 (SE 0.09), with an all schools mean of 2.83. The confidence intervals around the means of the majority of schools were wide, reflecting the relatively small number of respondents at each school or variability in student responses within schools. When we looked at student mean responses within each school, however, the SD of the mean was ≤0.50 at 90% of schools, indicating good intraschool agreement. The confidence intervals around the means for the three schools with the lowest ratings did not overlap those of five of the schools with the highest ratings. There were no substantive differences in school characteristics between those two groups.

FIG. 4.

Mean combined curriculum and preparedness ratings for each school with more than 10 student respondents (n = 47). School means with 95% confidence intervals around the SEM are displayed in ranked order.

Student comments

We asked students in open-ended questions to comment on different aspects of the curriculum at their school. When asked what additional topics they would like to see included in the curriculum, the most frequently mentioned were abortion and contraception (listed by 42% of the 406 students who responded to this question), sex/gender-specific information on any topic (20%), rape and domestic violence (20%), sexual orientation and gender identification (11%), female sexuality (9%), and adolescent girls' issues (5%). Female students were significantly more likely to request additional sex/gender-specific information.

When asked to identify strengths and weaknesses in their curricula, 15% of the 330 students who responded to this question cited the positive influence of a specific course/lecture, teacher, or approach (such as the use of simulated patients) on the teaching of women's health or sex/gender-specific factors. A smaller proportion identified areas of weakness, including the relegation of women's health teaching to obstetrics/gynecology or psychiatry with little contribution from internal medicine or other disciplines (6%), traditional views at their institution resulting in avoidance of controversial issues (6%), the marginalization of women's health topics to nonmainstream lectures/courses (2%), and unequal clinical experience in women's health (2%).

Students offered unique gender-specific comments to questions. Nine male students stated that there was too much teaching on women's health or that curricula have been “overcorrected” for women's health with “neglect” of men's health. One pointed out that there are also deficiencies in men's health and that many of the topics in the survey are not addressed in men either. Two male students voiced difficulties they face in acquiring clinical skills when women patients prefer to see only female providers. Four female students were concerned about “isolating” women's health to special lectures/courses and advocated for balanced information on both sexes.

Clinical training and learning environment

The survey also queried students about clinical training and the learning environment at their school. A high proportion (92%) had been trained using a live female patient actor. More than half (59%) received specific instruction on how to communicate with and counsel female patients. Eighty-six percent agreed that all students are treated equally, fairly, and with respect at their school or that student contributions in the classroom and in clinical settings are acknowledged and rewarded equally (81%).

Discussion

The results of this survey of predominantly female medical students at AMWA-affiliated schools suggest continued gaps in the teaching of women's health and sex/gender-specific content. Students' ratings of the adequacy of teaching in these areas showed only brief to moderate coverage of women's health and sex/gender-specific topics. Differences in ratings among each of the six curriculum categories included in the survey were small, with the category, sex and gender factors in common medical conditions, receiving the lowest rating. A relative lack of attention in curricula to the influence of sex and gender factors on medical conditions, compared with other women's health topics, is a pattern that was first reported in the 1994–1995 AAMC survey1 of medical school administrators and described most recently in a 2004 study that examined the women's health and sex and gender-specific content of medical school curricula.2 Reasons why this material is less well integrated may include a lack of awareness of data on sex and gender differences, the relative importance placed on this information, or uncertainly about how to integrate this content into curricula.2,16

Despite their low curriculum ratings, students perceived that they were moderately prepared to perform a selected set of clinical skills in female patients. In several areas related to reproductive health interviewing, examination and counseling skills, and screening for or management of a range of medical conditions in women, students' confidence in their skills was even higher. As the AAMC survey did not collect information on student competencies, we were not able to assess change in students' perceived clinical skills over time.

The disparity between students' overall perceptions of the adequacy of teaching and their self-reported preparedness is explained partly by the design and content of the survey. The curriculum assessment section included questions about coverage of basic science and other topics that did not have counterparts in the preparedness section. Among those curriculum topics that had related preparedness counterparts, there was generally good agreement between students' perceptions of the adequacy of teaching and their self-reported clinical skills. There were two exceptions where students rated their skills considerably higher than the adequacy of teaching of a topic. This mismatch may reflect students' overestimation of their skills, a lack of knowledge (i.e., not recognizing the importance of knowledge of female sexual response and dysfunction in taking a sexual history), or, more positively, the benefits of self-learning that many students employ to fill perceived gaps in their education. The validity and accuracy of student assessments have also been questioned, particularly self-assessments of performance.17–25 A recent literature review on physician self-assessment that excluded studies of medical students concluded that the ability of physicians to assess their performance is limited.25 In contrast, most studies of medical students suggest that their ability to accurately self-evaluate their performance is moderately good, particularly in the clinical domains included in our survey.17–23

Female student ratings were lower than those of their male colleagues, particularly in their assessment of the extent to which topics were integrated into curricula, and they were more likely to request additional sex/gender-specific teaching. Reasons for the disparity are uncertain but may reflect gender differences in students' knowledge, educational expectations, or perceptions about the importance of certain topics. (Some male students in the study commented that women's health topics have been overemphasized in teaching, which may partly explain male students' higher ratings.) Gender differences in self-assessment have also been reported in previous studies, with a tendency for male students to overestimate, and female students to underestimate, their performance.17,22

The presence of an AMWA chapter was also associated with lower ratings. Because AMWA student chapters provide women's health advocacy and education, students' awareness and expectations, as well as their motivation in responding to the survey, may be different at AMWA schools than at schools without AMWA representation. Another possibility is that AMWA chapters are established at schools where there is a perceived deficit in women's health teaching, leading to lower ratings.

School location in the central United States was associated with significantly higher mean combined ratings, whereas other school characteristics that might be expected to be associated with higher ratings, such as the proportion of tenured women faculty, the presence of a female dean, or a site of a federally funded women's health program, had no association. Quantitative differences in ratings were extremely small, however, and the importance of central location should be interpreted cautiously. We can only speculate on the reasons why major federally funded women's health programs were not associated with higher ratings. Even though the CoEs were funded to develop curricular models, curricular change is a prolonged process, and the successful integration of new content is dependent on several factors, including the institutional timetable for curricular revisions, agreement between departments on curricular priorities, resources and leadership, and the availability of knowledgeable and committed faculty.7,16,26 The CoEs may not have had the resources or a long enough timeframe to develop the interdisciplinary collaborations necessary to implement a comprehensive women's health and sex/gender-specific curriculum, and the models developed may benefit only a small number of students.26 Similarly, at schools with women's health research prowess, students may not benefit from this expertise. The lack of higher ratings at CoE schools compared with non-CoE schools may also reflect the presence of ongoing educational initiatives at non-CoE schools6,27 and new curricular tools available for use by all schools.13,14

Students' comments on the curriculum at their school underscore the need to address deficiencies in teaching. Based on the results of our survey and findings from previous studies,1–3 our suggestions to improve teaching include integrate women's health and sex/gender-specific information throughout the curriculum with a special focus on areas of identified gaps (e.g., gender identification, sexuality, interpersonal violence, certain reproductive topics, and sex/gender-specific information on medical conditions), ensure that all students have equal access to women's health clinical training, provide more teaching by faculty knowledgeable about this content, and place students' educational needs before belief systems that influence the inclusion or content of controversial topics.

Our study has several limitations. First, the respondents to our survey were not a random sample of U.S. medical students, and our findings may not be representative of all students. Second, the low number of responses from third and fourth year students relative to the total number of students in those years may limit the generalizability of our results. Students who did not respond may not have received or opened the online survey or were too busy or lacked motivation to participate. In addition, no students from 24 of the 125 medical schools responded, limiting our findings to the perceptions of respondents at those schools included in the study. If low or no student participation indicates a lack of institutional or student interest in or support of women's health and sex/gender-specific education, our findings may overestimate the adequacy of teaching and students' clinical skills in these subjects.

Second, lower ratings by female students and by students at AMWA schools, both of which were overrepresented in the study, may underestimate curriculum coverage of women's health and sex/gender-specific topics and students' preparedness to care for women. If, however, female or AMWA students were more knowledgeable about topics included in the survey or more discerning in their responses, our results may be a more informed assessment of schools' teaching. Third, although we designed the survey questions using published recommendations from interdisciplinary panels of experts and consideration of government offices' concepts of women's health, we could not include all women's health topics. Finally, our findings are based on students' assessments, not curriculum evaluations, and may not correlate with the actual teaching at schools.

Despite these limitations, our study has several strengths. To our knowledge, it is the only large study of students' perceptions of their education and training in women's health and sex and gender factors. Students from 81% of all U.S. schools responded to the survey, with a mean of 13 participating at each school. The quantitative results of the survey were similar to those of other studies that examined the curricular content of women's health education, and students' consistent comments in response to open-ended questions in the survey allowed us to identify common themes. The survey also allowed medical students to share their perspectives and to comment on issues not included elsewhere in the survey instrument.

Conclusions

Medical students in this study reported only brief to moderate coverage of women's health and sex/gender-specific topics in curricula; sex/gender-specific information on common medical disorders received the least coverage, a pattern that has persisted for more than a decade. Despite their low curriculum assessment, students reported moderate confidence in their ability to provide care to women over a broad range of clinical skills. Lower ratings by female students and by those at schools with an AMWA chapter may reflect differences in knowledge or educational expectations.

Footnotes

This project was supported in part by grant No. B01-6 from The Josiah Macy, Jr., Foundation, New York, NY, and under contract with the National Institutes of Health (NIH) (award No. B00098) funded by the NIH Office of Research on Women's Health, the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA), Office of Women's Health, and the Office on Women's Health, Office of the Secretary, Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS). The Macy Foundation grant supported the design and administration of the survey instrument and the development of the database for analysis. The NIH contract supported the data analysis and preparation of the findings for report. No federal funds were used to conduct the survey on which the findings are based.

The survey instrument was administered through a contract agreement between Yale University and ACTIONREACTION Technology Solutions, a private company based in New York City. The contract was funded by the Josiah Macy, Jr. Foundation. ACTIONREACTION was involved in the design and implementation of the survey instrument and in the development of the web-based database. It hosted and administered the survey instrument and database and aggregated data for reporting.

The project was exempted from review by the Yale University School of Medicine Human Investigation Committee (HIC) under the following parts of the federal regulations: 45 CFR Part 46.101(b)(2).

Acknowledgments

We thank AMWA senior leadership and staff for their support of the survey and role in its design and conduct and AMWA student leadership and members for their support of the survey and role in its implementation.

Disclaimer Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Women's Health in the Medical School Curriculum. Report of a Survey and Recommendations. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Services Administration, and the National Institutes of Health; 1996. HRSA-A-OEA-96-1. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Henrich JB. Viscoli CM. What do medical schools teach about women's health and gender differences? Acad Med. 2006;81:476. doi: 10.1097/01.ACM.0000222268.60211.fc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Keitt SK. Wagner C. Tong C. Marts SA. Positioning women's health curricula in U.S. medical schools. Med Gen Med. 2003;5:40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liaison Committee on Medical Education. 1997–1998 LCME annual medical school questionnaire. Part II (unpublished results); Chicago, IL: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liaison Committee on Medical Education. 1999–2000 LCME annual medical school questionnaire. Part II (unpublished results); Chicago, IL: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Women's Health Program University of Cincinnati and the Women's Healthcare Office Association of Professors of Gynecology Obstetrics. A guide to 4th year medical student electives in women's health. Results of a survey of Association of American Medical Colleges member institutions. 2002.

- 7.Henrich JB. Women's health education initiatives: Why have they stalled? Acad Med. 2004;79:283. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200404000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gwinner VM. Strauss JF., 3rd Milliken N. Donoghue GD. Implementing a new model of integrated women's health in academic health centers: Lessons learned from the National Centers of Excellence in Women's Health. J Womens Health Gend Based Med. 2000;9:979. doi: 10.1089/15246090050200006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Agenda for Research on Women's Health for the 21st Century. A report of the Task Force on the NIH Women's Health Research Agenda for the 21st Century. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health, Office of the Director, Office of Research on Women's Health; 1999. NIH Publication No. 99-4385. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Agency for Healthcare Research Quality. AHRQ Women's Health. www.ahcpr.gov/research/womenix.htm. [Jul 6;2006 ]. www.ahcpr.gov/research/womenix.htm

- 11.Institute of Medicine. Exploring the biological contributions to human health. Does sex matter? Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pinn VW. Sex and gender factors in medical studies: Implications for health and clinical practice. JAMA. 2003;289:397. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.4.397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.APGO Women's Healthcare Education Office. Women's health care competencies for medical students. Crofton, MD: APGO; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 14.APGO Women's Healthcare Education Office. Women's health care competencies for medical students: Taking steps to include sex and gender differences in the curriculum. Crofton, MD: APGO; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Barzansky B. Etzel SI. Medical schools in the United States, 2005–2006. JAMA. 2006;296:1147. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.9.1147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gwinner VM. Women's health as a model for change in academic medical centers: Lessons from the National Centers of Excellence in Women's Health. J Gend Specif Med. 2000;3:53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Coutts L. Rogers J. Predictors of student self-assessment accuracy during a clinical performance exam: Comparisons between over-estimators and under-estimators of SP-evaluated performance. Acad Med. 1999;74:S128. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199910000-00062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Edwards RK. Kellner KR. Sistrom CL. Magyari EJ. Medical student self-assessment of performance on an obstetrics and gynecology clerkship. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;188:1078. doi: 10.1067/mob.2003.249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fitzgerald JT. Gruppen LD. White CB. The influence of task formats on the accuracy of medical students' self-assessments. Acad Med. 2000;75:737. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200007000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Herbert WN. McGaghie WC. Droegemueller W. Riddle MH. Maxwell KL. Student evaluation in obstetrics and gynecology: Self- versus departmental assessment. Obstet Gynecol. 1990;76:458. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gordon MJ. A review of the validity and accuracy of self-assessments in health professions training. Acad Med. 1991;66:762. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199112000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gruppen LD. Garcia J. Grum CM, et al. Medical students' self-assessment accuracy in communication skills. (Erratum appears in Acad Med 1997;72:1126.) Acad Med. 1997;72:S57. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199710001-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Farnill D. Hayes SC. Todisco J. Interviewing skills: Self-evaluation by medical students. Med Educ. 1997;31:122. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.1997.tb02470.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Woolliscroft JO. TenHaken J. Smith J. Calhoun JG. Medical students' clinical self-assessments: Comparisons with external measures of performance and the students' self-assessments of overall performance and effort. Acad Med. 1993;68:285. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199304000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Davis DA. Mazmanian PE. Fordis M. Van Harrison R. Thorpe KE. Perrier L. Accuracy of physician self-assessment compared with observed measures of competence: A systematic review. JAMA. 2006;296:1094. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.9.1094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fife RS. Development of a comprehensive women's health program in an academic medical center: Experiences of the Indiana University National Center of Excellence in Women's Health. J Womens Health. 2003;12:869. doi: 10.1089/154099903770948096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zebrack JR. Mitchell JL. Davids SL. Simpson DE. Web-based curriculum. A practical and effective strategy for teaching women's health. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20:68. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.40062.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]