Abstract

Mitochondrial bioenergetic dysfunction in traumatic spinal cord and brain injury is associated with post-traumatic free radical–mediated oxidative damage to proteins and lipids. Lipid peroxidation by-products, such as 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal and acrolein, can form adducts with proteins and exacerbate the effects of direct free radical–induced protein oxidation. The aim of the present investigation was to determine and compare the direct contribution of 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal and acrolein to spinal cord and brain mitochondrial dysfunction. Ficoll gradient–isolated mitochondria from normal rat spinal cords and brains were treated with carefully selected doses of 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal or acrolein, followed by measurement of complex I– and complex II–driven respiratory rates. Both compounds were potent inhibitors of mitochondrial respiration in a dose-dependent manner. 4-Hydroxy-2-nonenal significantly compromised spinal cord mitochondrial respiration at a 0.1-μM concentration, whereas 10-fold greater concentrations produced a similar effect in brain. Acrolein was more potent than 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal, significantly decreasing spinal cord and brain mitochondrial respiration at 0.01 μM and 0.1 μM concentrations, respectively. The results of this study show that 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal and acrolein can directly and differentially impair spinal cord and brain mitochondrial function, and that the targets for the toxic effects of aldehydes appear to include pyruvate dehydrogenase and complex I–associated proteins. Furthermore, they suggest that protein modification by these lipid peroxidation products may directly contribute to post-traumatic mitochondrial damage, with spinal cord mitochondria showing a greater sensitivity than those in brain.

Key words: acrolein, 4-hydroxy 2-nonenal, oxidative stress, spinal cord injury, traumatic brain injury

Introduction

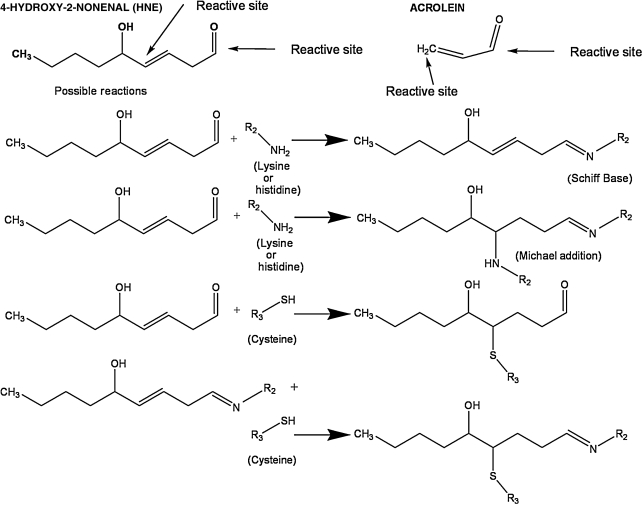

Acute spinal cord injury and traumatic brain injury both involve a series of secondary injury events that follow the initial primary injury, greatly exacerbating the neurodegeneration initiated by the mechanical trauma (Braughler and Hall, 1992; Hall, 1989). Extensive evidence has shown that free radical–induced lipid peroxidation (LP) plays a major role in the acute pathophysiology of spinal cord injury (Braughler and Hall, 1992; Carrico et al., 2009; Hall, 1989, 2001; Hall and Springer, 2004; Hillard et al., 2004; Sullivan et al., 2007; Xiong and Hall, 2009; Xiong et al., 2007, 2009), and traumatic brain injury (Ansari et al., 2008; Braughler and Hall, 1992; Deng-Bryant et al., 2008; Deng et al., 2007; Hall, 1989; Hall et al., 1999, 2004, 2005, 2010; Singh et al., 2006, 2007). Lipid peroxidation begins with the oxidation of polyunsaturated fatty acids (e.g., arachidonic, linoleic, and docosahexaenoic acids) in the cell, or in membrane phospholipids at their allylic carbon. The peroxidized polyunsaturated fatty acids undergo phospholipase-mediated hydrolysis and consequent disruption of the membrane phospholipid architecture, and loss of the function of phospholipid-dependent enzymes, ion channels, and structural proteins. However, in addition to LP-induced membrane damage, the peroxidized fatty acids ultimately give rise to aldehydic breakdown products, including 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal (4-HNE) and 2-propenal (acrolein). These aldehydes are highly reactive with cellular proteins via Schiff base and Michael adduct reactions with basic (e.g., lysine and histidine) and sulfhydryl (e.g., cysteine) containing amino acids (Petersen and Doorn, 2004; Stevens and Maier, 2008). These reactions, shown in Figure 1, have been shown to impair the function of a variety of cellular proteins, which could also contribute to post-traumatic secondary injury and the associated pathophysiology. Sources of post-traumatic reactive oxygen species (ROS) that result in toxic LP-inducing secondary injury include iron-dependent Fenton reactions, which result in hydroxyl radical production and peroxynitrite (PON)-derived free radicals (•OH, •NO2, and •CO3) (Braughler and Hall, 1992; Hall, 1989; Hall et al., 2010; Halliwell 1992, 2001; Huie and Padmaja, 1993; Szabo et al., 2007).

FIG. 1.

Representative chemical interactions demonstrating binding of lipid peroxidation–derived aldehydes (including 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal and acrolein) to proteins by formation of either Schiff bases or Michael adducts.

Free radical–mediated oxidative damage in acute spinal cord and brain trauma results in protein oxidation and mitochondrial dysfunction, largely due to their intrinsic ability to produce ROS as a by-product of the electron transport chain function, in addition to extramitochondrial ROS (Deng et al., 2007; Hall et al., 2004; Singh et al., 2006; Xiong and Hall, 2009; Xiong et al., 2007). Our previous work has shown that PON is able to directly attenuate mitochondrial function in injured brain (Singh et al., 2006) and spinal cord (Xiong et al., 2007, 2009) mitochondria, and that these effects are associated with increased 4-HNE-modified proteins. Moreover, direct application of PON to normal mitochondria replicates the effects of in vivo injury (Singh et al., 2007; Xiong et al., 2009). Although LP-induced membrane destruction may itself impair mitochondrial function, the LP-derived aldehydes such as 4-HNE and acrolein, which are known to be cytotoxic (Kruman et al., 1997; Lovell et al., 2001; Luo et al., 2005a; Sayre et al., 2008), may also play a role.

Thus the purpose of the current study was to examine the in vitro effects of 4-HNE and acrolein on the bioenergetics of isolated brain and spinal cord mitochondria.

Methods

Animals

All experiments were done using isolated mitochondria from 22 young adult (3- to 4-month-old) female Sprague-Dawley rats (Charles River Labs International, Portage, MI) that were fed and watered ad libitum. The animals were randomly cycling and were not tested for stage of the estrus cycle. All protocols used in this study were approved by the University of Kentucky Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee, and were consistent with the National Institutes of Health Guidelines for the Care and Use of Animals.

Chemicals

Acrolein was obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (Supelco, Bellefonte, PA), and 4-HNE from EMD Chemicals Inc. (Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany). Acrolein was stored at 4°C per the manufacturer's suggestion. Both chemicals were stored at −20°C as stock solutions of 10 mM concentration for the duration of each experiment. Working solutions for the dose-response studies were always prepared fresh by dilution in respiration buffer prior to beginning an experiment.

Isolation of Ficoll-purified mitochondria

Brain and spinal cord mitochondria were extracted as previously described, with some modifications (Singh et al., 2007; Sullivan et al., 2004). Briefly, the rats were decapitated and the brain and spinal cord rapidly removed. Brain cortical regions and a 2-cm mid-thoracic segment of spinal cord were dissected out in an ice-cold Petri dish containing isolation buffer (1 mM EGTA (215 mM mannitol, 75 mM sucrose, 0.1% BSA, 20 mM HEPES, and 1 mM EGTA, adjusted to a pH of 7.2 with KOH). Both brain cortical and spinal cord tissues were homogenized using Potter-Elvehjem homogenizers containing ice-cold isolation buffer. The tissue homogenates were centrifuged twice at 1300g for 3 min in an Eppendorf microcentrifuge at 4°C to remove cellular debris and nuclei, and the supernatant was further centrifuged at 13,000g for 10 min. The resulting crude mitochondrial pellet was subjected to nitrogen decompression to release synaptic mitochondria, using a nitrogen cell disruption bomb, at 4°C under a pressure of 1200 psi for 10 min. After nitrogen disruption, the mitochondrial pellet was resuspended in isolation buffer and layered on top of a discontinuous Ficoll gradient (7.5% and 10%), and centrifuged at 100,000g for 30 min. The mitochondrial pellets at the bottom were transferred to microfuge tubes, topped off with isolation buffer without EGTA, and centrifuged at 10,000g for 10 min at 4°C to yield a tighter pellet. The final mitochondrial pellet was resuspended in 25–50 μL isolation buffer without EGTA to yield a concentration of approximately 10 mg/mL. The protein concentration was determined using a BCA protein assay kit measuring absorbance at 562 nm with a BioTek Synergy HT plate reader (Winooski, VT).

Mitochondrial respiration studies

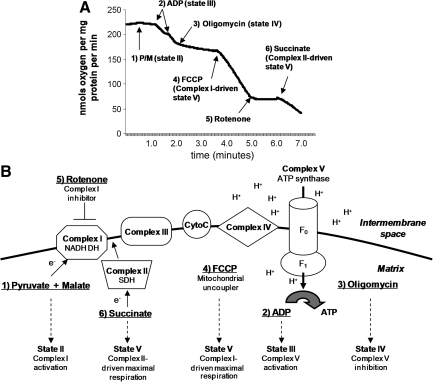

Mitochondrial respiratory rates were measured using a Clark-type electrode in a continuously stirred, sealed, and thermostatically controlled chamber (Oxytherm System; Hansatech Instruments Ltd., King's Lynn, Norfolk, U.K.) maintained at 37°C, as previously described (Singh et al., 2007; Sullivan et al., 2004). Mitochondria loaded into the chamber were normalized based on protein content (70 μg mitochondrial protein per run). The mitochondria were kept on ice prior to loading into a chamber 250 μL of KCl-based respiration buffer (125 mM KCl, 2 mM MgCl2, 2.5 mM KH2PO4, 0.1% BSA, and 20 mM HEPES at pH 7.2). The slope of the oxygen electrode trace corresponded to the respiratory rate (Fig. 2A shows a representative trace). After equilibrating for 1 min in respiration buffer at 37°C (state I respiration), the complex I substrates 5 mM pyruvate and 2.5 mM malate were added to the chamber in order to monitor the state II respiratory rate. In some experiments we used 5 mM glutamate (Sigma-Aldrich) and 2.5 mM malate to monitor state II respiration. Two boluses of 150 μM ADP were then added to the mitochondria to initiate the state III respiratory rate for 2 min, followed by the addition of 2 μM oligomycin to monitor the state IV respiration rate for an additional 2 min. For the measurement of the uncoupled respiratory rate (state V), 2 μmol/L FCCP was added to the mitochondria in the chamber, and oxygen consumption was monitored for another 2 min, followed by the addition of rotenone (1 μM) to completely block complex I-driven respiration. This was followed by the addition of 10 mmol/L succinate to monitor complex II-driven respiration. The electron transport system, substrates, and states are illustrated in Figure 2B. The respiratory control ratio (RCR) was calculated by dividing state III oxygen consumption (defined as the rate of respiration in the presence of ADP, second bolus addition) by state IV oxygen consumption (the rate obtained in the presence of oligomycin). Mitochondria were prepared fresh for every experiment and were used immediately for in vitro respiration assays. Treatment with 4-HNE or acrolein was performed in the oxytherm chamber for 5 min prior to the addition of substrates. Baseline mitochondrial oxygen consumption and RCRs were measured before 4-HNE or acrolein treatment, and verified again at the end of every experiment. Mitochondria from individual rats were used for brain respiratory assays; for spinal cord respiration, mitochondrial pellets from two rats were pooled.

FIG. 2.

(A) A typical oxymetric trace demonstrating mitochondrial bioenergetics of Ficoll-purified mitochondria. Rates of respiration were estimated as nanomoles of oxygen consumed per milligram mitochondrial protein, and were measured from the slopes of the trace following addition of various substrates as indicated. (B) The mitochondrial electron transport system is illustrated here to show the sites of substrate utilization and inhibitor action. After equilibrating for 1 min in respiration buffer at 37°C, the complex I substrates 5 mmol/L pyruvate and 2.5 mmol/L malate were added to the chamber in order to monitor the state II respiratory rate. Two boluses of 150 μmol/L of adenosine diphosphate (ADP) were then added to the mitochondria to initiate the state III respiratory rate for 2 min, followed by the addition of 2 μmol/L of oligomycin to monitor the state IV respiration rate for an additional 2 min. For the measurement of the uncoupled respiratory rate (state V), 2 μmol/L FCCP was added to the mitochondria in the chamber, and oxygen consumption was monitored for another 2 min, followed by the addition of rotenone (1 μM) to completely block complex I-driven respiration. This was followed by the addition of 10 mmol/L succinate to monitor maximal complex II-driven respiration (state V; ATP, adenosine triphosphate; SDH, succinate dehydrogenase; FCCP, carbonylcyanide p-trifluoromethoxyphenylhydrazone; NADH DH, reduced nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide dehydrogenase P/M, pyruvate + malate).

The concentrations of 4-HNE and acrolein used were 0.01, 0.1, 1, or 10 μM, for which 2.5 μL of 100× working solution was added to respiration buffer containing live mitochondria equivalent to 70 μg protein. Thus the concentrations of 4-HNE or acrolein per milligram of protein were 0.0357, 0.3571, 3.5714, and 35.7142 picomoles per milligram mitochondrial protein.

Statistical analysis

All results are expressed as means ± SEM. Bioenergetics data were analyzed by two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by post-hoc analysis using Fisher's Protected Least Significant Difference test.

Results

Bioenergetics of mitochondria isolated from spinal cord and brain

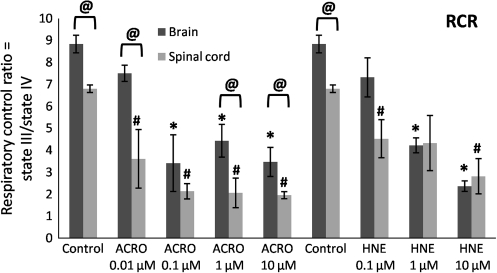

Mitochondria isolated from the spinal cord and brain tissue of healthy rats were verified to be metabolically intact and well-coupled, exhibiting a respiratory control ratio (RCR, ratio of state III to state IV respiration) above 5, in accordance with previous studies (Singh et al., 2007; Xiong and Hall, 2009). Interestingly, the oxygen consumption traces showed that untreated mitochondria obtained from spinal cords had significantly lower mean RCRs than those from brains (6.9 versus 8.8), as shown in Figure 3.

FIG. 3.

Dose-dependent effects of acrolein (ACRO) and 4-HNE (HNE) on respiratory dysfunction of Ficoll-purified mitochondria isolated from spinal cord and brain. Respiratory control ratio (RCR) was calculated by dividing state III oxygen consumption (defined as the rate of oxygen consumption after addition of adenosine diphosphate) by state IV oxygen consumption (the rate in the presence of oligomycin). Data are presented as means ± standard error of the mean for n = 3 per dose (#p < 0.05 compared with control spinal cord mitochondria; @p < 0.05 comparing tissue [spinal cord versus brain] as determined by two-way analysis of variance and Fisher's Protected Least Significant Difference post-hoc test).

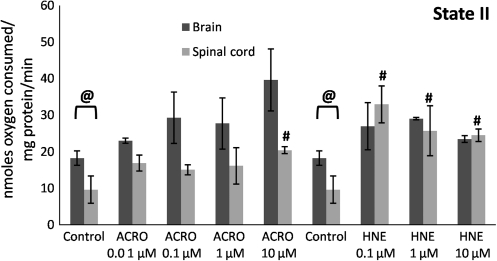

Intrinsic differences in mitochondria isolated from brain and spinal cord were also evident upon examination of the individual states, as evidenced by significant differences between rates of untreated (control) mitochondria (Figs. 4–8 @p < 0.05).

FIG. 4.

Mitochondrial state II respiratory rates following exposure of Ficoll-purified mitochondria from spinal cord and brain to increasing doses of acrolein (0.01–10 μM), and 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal (HNE; 0.1–10 μM). Respiratory rates were determined by measuring the slopes of the oxymetric traces obtained from each experiment following addition of the substrates pyruvate and malate. Data are expressed as nanomoles of oxygen per milligram of isolated mitochondrial protein. Data are presented as means ± standard error of the mean for n = 3 per dose (*p < 0.05 compared with control [untreated] brain mitochondria; #p < 0.05 compared with control spinal cord mitochondria; @p < 0.05 comparing tissue [spinal cord versus brain] as determined by two-way analysis of variance and Fisher's Protected Least Significant Difference post-hoc test).

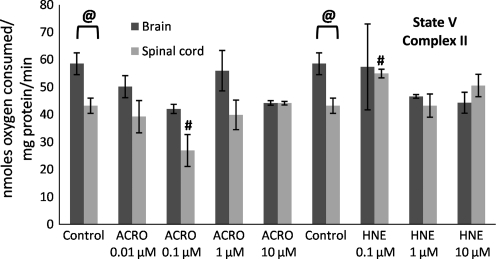

FIG. 8.

Mitochondrial state V (complex II) respiratory rates following exposure of Ficoll-purified mitochondria from spinal cord and brain to increasing doses of acrolein (0.01–10 μM) and 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal (HNE; 0.1–10 μM). Respiratory rates were determined by measuring the slopes of the oxymetric traces obtained from each experiment following sequential addition of substrates, inhibition of complex I with rotenone, and providing the complex II substrate succinate in the presence of the uncoupler FCCP. Data are expressed as nanomoles of oxygen per milligram of isolated mitochondrial protein. Data are presented as means ± standard error of the mean for n = 3 per dose (#p < 0.05 compared with control spinal cord mitochondria; @p < 0.05 comparing tissue [spinal cord versus brain] as determined by two-way analysis of variance and Fisher's Protected Least Significant Difference post-hoc test; FCCP, carbonylcyanide p-trifluoromethoxyphenylhydrazone;).

Impairment of spinal cord and brain mitochondrial RCRs following acrolein and 4-HNE treatment

To investigate the ability and potency of acrolein and 4-HNE to produce spinal cord and brain mitochondrial bioenergetic dysfunction, we exposed isolated spinal cord and brain mitochondria to various concentrations of acrolein and 4-HNE ranging from 0.01–10 μM. A representative trace and diagram illustrating the various respiratory states is shown in Figure 2. The RCR decreases as mitochondria undergo uncoupling of the electron transport chain. This can occur due to either a decrease in state III (lower complex I activity), or an increase in state IV (proton leak) or both. A significant impairment was observed in spinal cord mitochondria (Fig. 3) treated with 0.01 μM acrolein, with the mean RCR decreasing from an initial 6.9 to 3.4 (49% control). In contrast, a 10-fold greater concentration of acrolein (0.1 μM) was necessary to produce a significant decrease in brain mitochondrial RCRs, from a mean of 8.8 to 4.0 (46% control). A dose-dependent decrease in RCRs was observed both in spinal cord and brain (Fig. 3) mitochondria following 4-HNE treatment. Pre-treatment of isolated mitochondria with 4-HNE significantly compromised spinal cord respiration at a 0.1 μM concentration, decreasing the mean RCR from an initial 6.9 to 4.6 (67% control). In contrast, a 10-fold greater concentration of 4-HNE (1 μM) was necessary to produce a significant decrease in brain mitochondrial RCRs, from a mean of 8.8 to 4.3 (48% control).

Impairment of spinal cord and brain mitochondrial bioenergetics following acrolein and 4-HNE treatment

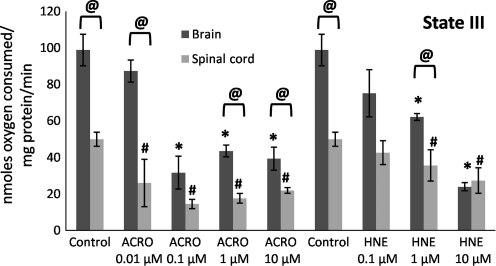

An expanded analysis of the effects of acrolein and 4-HNE on spinal cord and brain mitochondrial bioenergetics was performed in which oxygen consumption was also assessed in the presence of the substrates pyruvate + malate. Pyruvate requires activity of the mitochondrial enzyme pyruvate dehydrogenase (PDH), which converts pyruvate to acetyl-CoA which then enters the Krebs cycle. The slopes from the oxygen consumption traces were first measured to assess pyruvate + malate–driven state II, III, IV, V (complex I,) and V (complex II) respiration rates (see representative trace in Fig. 2). Following initial measurement of state I respiration (absence of complex I substrates), mitochondria were fueled by pyruvate and malate to visualize state II respiration (Fig. 4). Although no significant difference was observed in state II respiration of brain or spinal cord mitochondria following acrolein treatment, 4-HNE caused a significant increase in spinal cord mitochondrial state II (Fig. 4). State III showed a significant dose-dependent decline with acrolein pretreatment in both spinal cord (at 0.01 μM) and brain mitochondria (at 0.1 μM; Fig. 5).

FIG. 5.

Mitochondrial state III respiratory rates following exposure of Ficoll-purified mitochondria from spinal cord and brain to increasing doses of acrolein (0.01–10 μM) and 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal (HNE; 0.1–10 μM). Respiratory rates were determined by measuring the slopes of the oxymetric traces obtained from each experiment following the addition of adenosine diphosphate after the addition of pyruvate and malate. Data are expressed as nanomoles of oxygen per milligram of isolated mitochondrial protein. Data are presented as means ± standard error of the mean for n = 3 per dose (*p < 0.05 compared with control [untreated] brain mitochondria; #p < 0.05 compared with control spinal cord mitochondria; @p < 0.05 comparing tissue [spinal cord versus brain] as determined by two-way analysis of variance and Fisher's Protected Least Significant Difference post-hoc test).

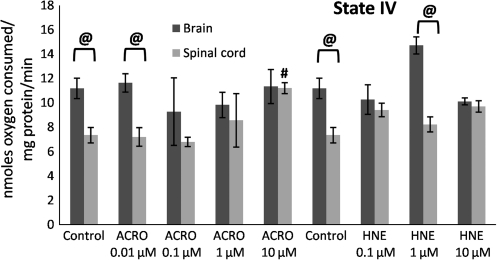

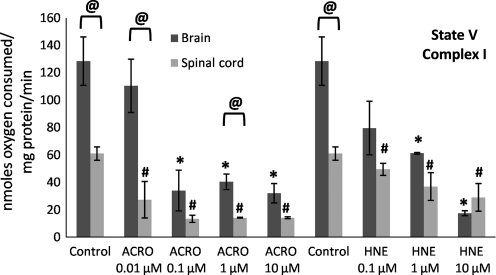

State III (presence of ADP) respiratory rates significantly decreased as a function of increasing acrolein and 4-HNE exposure (Fig. 5), which explains the decrease in the RCRs seen in Figure 3. In contrast, an increase in state IV (presence of oligomycin) respiration was not observed, except following treatment with 10 μM acrolein. Therefore an increase in state IV was not a major contributing factor in the dose-dependent lowering of the RCRs at the lower concentrations (Fig. 6), although this may be an important contributing factor at higher doses of reactive aldehydes, particularly acrolein. State V-complex I (uncoupled in the presence of FCCP) respiration showed a similar dose response to acrolein and 4-HNE treatment to that seen with state III (Fig. 7), suggesting impairment of PDH and/or complex I. In contrast, state V-complex II respiration was not significantly impaired by acrolein or 4-HNE, suggesting that the LP products primarily and specifically affected upstream respiratory elements (Fig. 8). Similarly to the decreases observed in the RCRs (Fig. 3), spinal cord mitochondrial state III and state V respiration rates (both indicative of complex I activity) were significantly decreased at a 4-HNE concentration of 0.1 μM, whereas a concentration of 1 μM was needed for a similar effect in the brain (Figs. 5 and 7). Overall, lower concentrations of acrolein (0.01 and 0.1 μM) produced significant reductions in spinal cord and brain mitochondrial RCRs and respiratory states III and V, in contrast to the higher concentrations of 4-HNE required for mitochondrial impairment (0.1 and 1 μM).

FIG. 6.

Mitochondrial state IV respiratory rates following exposure of Ficoll purified mitochondria from spinal cord and brain to increasing doses of acrolein (0.01–10 μM) and 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal (HNE; 0.1–10 μM). Respiratory rates were determined by measuring the slopes of the oxymetric traces obtained from each experiment following oligomycin treatment. Data are expressed as nanomoles of oxygen per milligram of isolated mitochondrial protein. Data are presented as means ± standard error of the mean for n = 3 per dose (#p < 0.05 compared with control spinal cord mitochondria; @p < 0.05 comparing tissue [spinal cord versus brain] as determined by two-way analysis of variance and Fisher's Protected Least Significant Difference post-hoc test).

FIG. 7.

Mitochondrial state V (complex I) respiratory rates following exposure of Ficoll-purified mitochondria from spinal cord and brain to increasing doses of acrolein (0.01–10 μM) and 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal (HNE; 0.1–10 μM). Respiratory rates were determined by measuring the slopes of the oxymetric traces obtained from each experiment following sequential addition of substrates and the uncoupler FCCP. Data are expressed as nanomoles of oxygen per milligram of isolated mitochondrial protein. Data are presented as means ±standard error of the mean for n = 3 per dose (*p < 0.05 compared with control [untreated] brain mitochondria; #p < 0.05 compared with control spinal cord mitochondria; @p < 0.05 comparing tissue [spinal cord versus brain] as determined by two-way analysis of variance and Fisher's Protected Least Significant Difference post-hoc test; FCCP, carbonylcyanide p-trifluoromethoxyphenylhydrazone;).

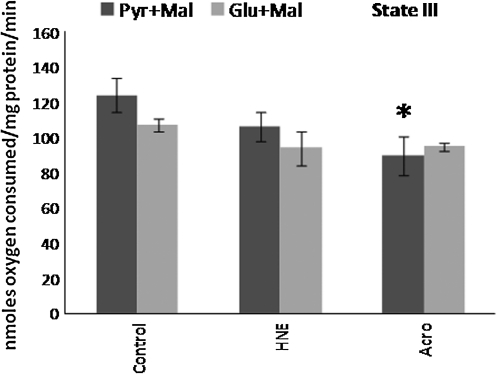

Pyruvate dehydrogenase is a target of acrolein and 4-HNE-mediated mitochondrial bioenergetic impairment

In the next set of experiments, the effects of acrolein and 4-HNE on rat brain mitochondrial bioenergetics were compared using two different sets of substrates: pyruvate + malate versus glutamate + malate The substitution of glutamate for pyruvate drives complex I downstream from PDH. Thus by comparing the differences in the sensitivity of mitochondrial bioenergetics to acrolein or 4-HNE when mitochondrial respiration was driven by pyruvate + malate versus glutamate +malate, we were able to determine the possible role of PDH as a target for the two LP-associated aldehydes.

State III respiration was not significantly different in brain mitochondria pretreated with either 1 μM acrolein or 1 μM 4-HNE when glutamate + malate was employed as the substrate pair (Fig. 9). However, in separate experiments, the effects of the addition of pyruvate and malate to the isolated mitochondria were tested on state III respiration, and the results obtained for state III were different from those observed for glutamate + malate, as shown in Figure 9. Similarly, RCRs for glutamate + malate with 4-HNE or acrolein pretreatment were not significantly different from those of mitochondria treated with glutamate + malate alone (data not shown). This again was unlike the results obtained with pyruvate + malate, for which RCRs were significantly compromised following both acrolein and 4-HNE treatment (e.g., Figure 3). Clearly, the lack of effect of acrolein and 4-HNE on glutamate + malate–mediated respiration, and the sensitivity of respiration in the presence of pyruvate + malate as substrates suggests that acrolein and 4-HNE may act in large part via a specific toxic effect on PDH.

FIG. 9.

Mitochondrial state III respiratory rates following exposure of Ficoll-purified mitochondria from brain to 1 μM acrolein or 1 μM 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal (HNE) in the presence of either pyruvate + malate (Pyr + Mal) or glutamate + malate (Glu + Mal) as substrates. Respiratory rates were determined by measuring the slopes of the oxymetric traces obtained from each experiment following the addition of adenosine diphosphate. Data are expressed as nanomoles of oxygen per milligram of isolated mitochondrial protein. Data are presented as means ± standard error of the mean for n = 4 per dose (*p < 0.05 compared with control [untreated] brain mitochondria with pyruvate + malate as determined by two-way analysis of variance and Fisher's Protected Least Significant Difference post-hoc test). No significant difference was observed in either acrolein or 4-HNE pre-treated mitochondria utilizing glutamate + malate as substrate, compared to untreated controls.

Discussion

The results of this study demonstrate that the reactive aldehydes 4-HNE and acrolein can directly and differentially impair spinal cord and brain mitochondrial function. Our bioenergetics analysis was performed following pre-incubation of isolated mitochondria from individual healthy rats with nanomolar to micromolar range doses of 4-HNE or acrolein. The doses were chosen based on previously reported concentrations in healthy and diseased tissue (Lovell et al., 2001; Luo et al., 2005b; Petersen and Doorn, 2004; Stevens and Maier, 2008). Although both aldehydes diminished pyruvate + malate–driven complex I activity, acrolein consistently appeared to be a more potent inhibitor of mitochondrial function than 4-HNE in both tissues. This may be a consequence of the known higher reactivity of acrolein due to its greater electrophilicity, which is potentiated by its smaller size, allowing it to diffuse into isolated mitochondria faster and react with proteins more rapidly. Also, 4-HNE is more lipophilic, which could cause it to more avidly reside in the mitochondrial membrane bilayer, lessening its ability to reach and react with electron transport chain proteins. Unlike the effects of 4-HNE and acrolein seen on complex I–driven mitochondrial respiration (state III and state V), maximum complex II–driven respiration (state V in the presence of succinate) did not show a similar dose-dependent decrease. These results would suggest that the ubiquinone or cytochrome components of complex II were not affected by acrolein or 4-HNE. Such differences in sensitivity between complex I and II have been observed in other studies as well (Parker et al., 1984; Sims et al., 2000). This is also in agreement with previous reports that complex I is more sensitive to oxidative modification, lowered efficiency, and consequent increased production of ROS (Boveris et al., 1976; Boveris and Chance, 1973; Cino and Del Maestro, 1989; Liu et al., 2002; McLennan and Degli Esposti, 2000; Navarro and Boveris, 2007; Turrens and Boveris, 1980). Interestingly, a direct effect on complex I was also observed at the highest concentration of acrolein (10 μM), as was indicated by significant elevations in state IV and state V respiration, which would suggest a proton leak under more severe conditions. Thus, in addition to substrates, the dose and type of reactive aldehyde exposure may determine the specific protein targets affected and the severity of the impairment.

In addition, our results demonstrate a specific effect of acrolein and 4-HNE on complex I respiration utilizing pyruvate + malate as substrates, but not glutamate + malate. Since pyruvate's ability to drive mitochondrial respiration requires normal activity of the enzyme PDH, which converts pyruvate to acetyl-CoA, the selective effect of acrolein and 4-HNE on pyruvate + malate–, but not glutamate + malate–driven bioenergetics, indicates that PDH is also a target of the LP-derived reactive aldehydes. Similar differences in sensitivity were observed in isolated rat brain mitochondria treated with hydrogen peroxide (Sims et al., 2000).

Lipid peroxidation and oxidative modification of proteins contribute to the pathophysiology of various neurodegenerative diseases and models (Butterfield and Kanski, 2001; Halliwell, 1992, 2001; Jenner and Olanow, 2006; Nunomura et al., 2007; Perez-Pinzon et al., 2005; Sayre et al., 2008; Sullivan and Brown, 2005; Szabo et al., 2007), including traumatic spinal cord and brain injuries (Deng et al., 2007; Jin et al., 2004; Lifshitz et al., 2004; Singh et al., 2006; Sullivan et al., 2004; Xiong et al., 2007). Although an important role of LP has been established in post-traumatic secondary injury in traumatic spinal cord and brain injury models (Ansari et al., 2008; Braughler and Hall, 1992; Carrico et al., 2009; Deng et al., 2007; Hall et al., 2004, 2010; Picklo et al., 1999; Xiong et al., 2007), the extent of involvement of the LP-derived by-products 4-HNE and acrolein themselves in the pathophysiology of neurotrauma is unclear. The role of acrolein in oxidative damage has been primarily studied in non-neurological systems, both as an environmental toxin (exogenous sources including cigarette smoke, vehicle exhaust fumes, and inhaled vapors from cooking oils during frying), and as an endogenously-produced compound (for example, as a metabolite of the chemotherapeutic agent cyclophosphamide; Stevens and Maier, 2008). In contrast, the involvement and increased levels of acrolein in various neurodegenerative diseases and in CNS mitochondrial damage has only recently emerged (Ansari et al., 2008; Calingasan et al., 1999; Lovell et al., 2001; Luo et al., 2005a, 2005b; Luo and Shi, 2004, 2005; Picklo and Montine, 2001). Both protein-bound 4-HNE and acrolein show elevated levels within 1–3 h following brain or spinal cord injury, with a sustained increase for 24–72 h following injury in rodent models (Ansari et al., 2008; Deng et al., 2007; Hall et al., 2004; Singh et al., 2006; Xiong et al., 2007). A recent report using an ex vivo model of spinal cord injury demonstrated the ability of acrolein to diffuse into and damage uninjured tissue, as well as exacerbate damage in the injured tissue (Hamann et al., 2008a), suggesting a potential role in secondary injury. A sustained elevation of 4-HNE and acrolein would greatly increase the likelihood of the oxidative modification of proteins, along with overwhelming of antioxidant systems and consequent neuronal damage. This, combined with its property of diffusibility, would make acrolein, and to a lesser extent 4-HNE, potent neurotoxins with potentially long-lasting and far-reaching effects. Although the physiological levels of these reactive aldehydes in the microenvironment of brain and spinal cord mitochondria following traumatic injury are not known, the doses for our experiments were chosen based on previous reports of whole-tissue concentrations of 0.7–5 nmol/mg protein in control and Alzheimer's disease brains (Lovell et al., 2001). In addition, brain mitochondrial inhibition has been shown to occur in vitro at concentrations of acrolein and 4-HNE ranging between 0.5 and 200 μM (Lovell et al., 2001; Luo and Shi, 2004; Luo and Shi, 2005; Picklo et al., 1999), and even as high as 0.5 μmol/mg protein (Picklo and Montine, 2001).

Another important observation in this study was that the spinal cord mitochondria responded differently to 4-HNE and acrolein than brain. On the whole, spinal cord mitochondria showed a significant decrease in RCR and state III and state V respiration at lower concentrations of 4-HNE or acrolein than brain mitochondria. It has previously been suggested that there may be intrinsic differences in mitochondria derived from different tissue sources (Andreyev and Fiskum, 1999; Sullivan et al., 2004). For example, spinal cord mitochondria were shown to generate higher levels of free radicals and displayed a greater sensitivity to attack by free radicals/oxidants than brain mitochondria (Sullivan et al., 2004). Our results support and extend these observations, demonstrating differences in both the bioenergetics of untreated mitochondria isolated from spinal cord and brain, as well as in sensitivity to reactive aldehyde treatment. The underlying mechanisms that would explain these intrinsic differences need to be evaluated further. For example, the metabolism of 4-HNE and/or acrolein can differ in mitochondria from these two sets of tissues (Hill et al., 2009). The neuronal and glial composition of these two tissues, the extent of transport necessary for mitochondria to reach synaptic targets, and the different energetic requirements of brain versus spinal cord neurons, are some of the other potential contributing factors. Previously, higher levels of endogenous superoxide, more 4-HNE-bound protein, elevated nucleic acid oxidation, increased sensitivity of mitochondrial permeability transition to calcium, and lower complex I activity, were described in spinal cord mitochondria compared to brain mitochondria (Sullivan et al., 2004).

In summary, our study provides the first detailed and direct comparison of the dose-dependent bioenergetic consequences of 4-HNE and acrolein exposure in spinal cord and brain mitochondria. We show that spinal cord mitochondria are more sensitive to these aldehydes than brain mitochondria. This is a unique and important observation that suggests that interfering with lipid peroxidative damage and functional impairment in the injured spinal cord may be more challenging than in the case of the injured brain. Additionally, we found that acrolein, the more understudied of the two neurotoxic aldehydes, is a more potent inhibitor of mitochondrial bioenergetics than 4-HNE, suggesting that interfering with acrolein's neurotoxicity with potential acrolein-scavenging drugs may be critically important as an approach to counteracting post-traumatic lipid peroxidative damage. The results provide a basis for the future design of in vitro experiments involving the evaluation of scavengers of these two toxic aldehydes prior to preclinical studies. Potential scavengers include hydrazine derivatives such as aminoguanidine, hydralazine, and carnosine (Burcham et al., 2002; Glavani et al., 2008; Hall et al., 2010). Interestingly, a recent study showed that hydralazine was able to protect against acrolein-mediated as well as compression injury in an ex vivo experimental model of spinal cord injury (Hamann et al., 2008b). Another potential approach to alleviate the “aldehyde load” may be to pharmacologically enhance their metabolism via induction of enzymes such as aldehyde dehydrogenases, carbonyl reductases, and aldo-keto reductases (Ellis, 2007; Jia et al., 2009).

In conclusion, the results of this study support a differential mitochondrial susceptibility to oxidative stress in the spinal cord compared to brain, and have implications for the future development of targeted neuroprotective therapies after acute traumatic brain or spinal cord injury.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by funding from the National Institutes of Health: NIH-NINDS 1F32NS063744-01 (R.A.V.); NIH-NIDA 1T32DA022738-01 (E.D.H.); NIH-NINDS 1P30NS051220-01 (E.D.H.); and the Kentucky Spinal Cord and Head Injury Research Trust Grant #6-5 (E.D.H.). We thank Dr. Malhar Jhaveri and Dr. Manan Jhaveri for assistance with the statistical analyses. Also we thank Drs. Bradford Hill and Daniel Conklin for sharing their valuable suggestions on storage and handling of acrolein.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- Andreyev A. Fiskum G. Calcium induced release of mitochondrial cytochrome c by different mechanisms selective for brain versus liver. Cell Death Differ. 1999;6:825–832. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4400565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ansari M.A. Roberts K.N. Scheff S.W. Oxidative stress and modification of synaptic proteins in hippocampus after traumatic brain injury. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2008;45:443–452. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2008.04.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boveris A. Cadenas E. Stoppani A.O. Role of ubiquinone in the mitochondrial generation of hydrogen peroxide. Biochem. J. 1976;156:435–444. doi: 10.1042/bj1560435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boveris A. Chance B. The mitochondrial generation of hydrogen peroxide. General properties and effect of hyperbaric oxygen. Biochem. J. 1973;134:707–716. doi: 10.1042/bj1340707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braughler J.M. Hall E.D. Involvement of lipid peroxidation in CNS injury. J. Neurotrauma. 1992;9(Suppl. 1):S1–S7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burcham P.C. Kaminskas L.M. Fontaine F.R. Petersen D.R. Pyke S.M. Aldehyde-sequestering drugs: tools for studying protein damage by lipid peroxidation products. Toxicology. 2002;181–182:229–236. doi: 10.1016/s0300-483x(02)00287-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butterfield D.A. Kanski J. Brain protein oxidation in age-related neurodegenerative disorders that are associated with aggregated proteins. Mech. Ageing Dev. 2001;122:945–962. doi: 10.1016/s0047-6374(01)00249-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calingasan N.Y. Uchida K. Gibson G.E. Protein-bound acrolein: a novel marker of oxidative stress in Alzheimer's disease. J. Neurochem. 1999;72:751–756. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1999.0720751.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrico K.M. Vaishnav R.A. Hall E.D. Temporal and spatial dynamics of peroxynitrite-induced oxidative damage after spinal cord contusion injury. J. Neurotrauma. 2009;26:1369–1378. doi: 10.1089/neu.2008-0870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cino M. Del Maestro R.F. Generation of hydrogen peroxide by brain mitochondria: the effect of reoxygenation following postdecapitative ischemia. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1989;269:623–638. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(89)90148-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng-Bryant Y. Singh I.N. Carrico K.M. Hall E.D. Neuroprotective effects of tempol, a catalytic scavenger of peroxynitrite-derived free radicals, in a mouse traumatic brain injury model. J. Cereb. Blood. Flow. Metab. 2008;28:1114–1126. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2008.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng Y. Thompson B.M. Gao X. Hall E.D. Temporal relationship of peroxynitrite-induced oxidative damage, calpain-mediated cytoskeletal degradation and neurodegeneration after traumatic brain injury. Exp. Neurol. 2007;205:154–165. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2007.01.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis E.M. Reactive carbonyls and oxidative stress: Potential for therapeutic intervention. Pharmacol. Ther. 2007;115:13–24. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2007.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glavani S. Coatrieux C. Elbaz M. Grazide M. Thiers J. Parini A. Uchida K. Kamar N. Rostaing L. Baltas M. Salvayre R. Negre-Salvayre A. Carbonyl scavenger and antiatherogenic effects of hydrazine derivatives. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2008;45:1457–1467. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2008.08.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall E.D. Detloff M.R. Johnson K. Kupina N.C. Peroxynitrite-mediated protein nitration and lipid peroxidation in a mouse model of traumatic brain injury. J. Neurotrauma. 2004;21:9–20. doi: 10.1089/089771504772695904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall E.D. Free radicals and CNS injury. Crit. Care Clin. 1989;5:793–805. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall E.D. Kupina N.C. Althaus J.S. Peroxynitrite scavengers for the acute treatment of traumatic brain injury. Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 1999;890:462–468. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb08025.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall E.D. Pharmacological treatment of acute spinal cord injury: how do we build on past success? J. Spinal Cord Med. 2001;24:142–146. doi: 10.1080/10790268.2001.11753571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall E.D. Springer J.E. Neuroprotection and acute spinal cord injury: a reappraisal. NeuroRx. 2004;1:80–100. doi: 10.1602/neurorx.1.1.80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall E.D. Sullivan P.G. Gibson T.R. Pavel K.M. Thompson B.M. Scheff S.W. Spatial and temporal characteristics of neurodegeneration after controlled cortical impact in mice: more than a focal brain injury. J. Neurotrauma. 2005;22:252–265. doi: 10.1089/neu.2005.22.252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall E.D. Vaishnav R.A. Mustafa A.G. Antioxidant therapies for traumatic brain injury. Neurotherapeutics. 2010;7:51–61. doi: 10.1016/j.nurt.2009.10.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halliwell B. Reactive oxygen species and the central nervous system. J. Neurochem. 1992;59:1609–1623. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1992.tb10990.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halliwell B. Role of free radicals in the neurodegenerative diseases: therapeutic implications for antioxidant treatment. Drugs Aging. 2001;18:685–716. doi: 10.2165/00002512-200118090-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamann K. Durkes A. Ouyang H. Uchida K. Pond A. Shi R. Critical role of acrolein in secondary injury following ex vivo spinal cord trauma. J. Neurochem. 2008a;107:712–721. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2008.05622.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamann K. Nehrt G. Ouyang H. Duerstock B. Shi R. Hydralazine inhibits compression and acrolein-mediated injuries in ex vivo spinal cord. J. Neurochem. 2008b;104:708–718. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2007.05002.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hillard V.H. Peng H. Zhang Y. Das K. Murali R. Etlinger J.D. Zeman R.J. Tempol, a nitroxide antioxidant, improves locomotor and histological outcomes after spinal cord contusion in rats. J. Neurotrauma. 2004;21:1405–1414. doi: 10.1089/neu.2004.21.1405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill B.G. Awe S.O. Vladykovskaya E. Ahmed Y. Liu S.Q. Bhatnagar A. Srivastava S. Myocardial ischaemia inhibits mitochondrial metabolism of 4-hydroxy-trans-2-nonenal. Biochem. J. 2009;417:513–524. doi: 10.1042/BJ20081615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huie R.E. Padmaja S. The reaction of no with superoxide. Free Radic. Res. Commun. 1993;18:195–199. doi: 10.3109/10715769309145868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenner P. Olanow C.W. The pathogenesis of cell death in Parkinson's disease. Neurology. 2006;66:S24–S36. doi: 10.1212/wnl.66.10_suppl_4.s24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia Z. Zhu H. Li Y. Misra H. Cruciferous nutraceutical 3H-1,2-dithiole-3-thione protects human primary astrocytes against neurocytotoxicity elicited by MPTP, MPP+, 6-OHDA, HNE and Acrolein. Neurochem. Res. 2009;34:1924–1934. doi: 10.1007/s11064-009-9978-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin Y. McEwen M.L. Nottingham S.A. Maragos W.F. Dragicevic N.B. Sullivan P.G. Springer J.E. The mitochondrial uncoupling agent 2,4-dinitrophenol improves mitochondrial function, attenuates oxidative damage, and increases white matter sparing in the contused spinal cord. J. Neurotrauma. 2004;21:1396–1404. doi: 10.1089/neu.2004.21.1396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kruman I. Bruce-Keller A.J. Bredesen D. Waeg G. Mattson M.P. Evidence that 4-hydroxynonenal mediates oxidative stress-induced neuronal apoptosis. J. Neurosci. 1997;17:5089–5100. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-13-05089.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lifshitz J. Sullivan P.G. Hovda D.A. Wieloch T. McIntosh T.K. Mitochondrial damage and dysfunction in traumatic brain injury. Mitochondrion. 2004;4:705–713. doi: 10.1016/j.mito.2004.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y. Fiskum G. Schubert D. Generation of reactive oxygen species by the mitochondrial electron transport chain. J. Neurochem. 2002;80:780–787. doi: 10.1046/j.0022-3042.2002.00744.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovell M.A. Xie C. Markesbery W.R. Acrolein is increased in Alzheimer's disease brain and is toxic to primary hippocampal cultures. Neurobiol. Aging. 2001;22:187–194. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(00)00235-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo J. Robinson J.P. Shi R. Acrolein-induced cell death in PC12 cells: role of mitochondria-mediated oxidative stress. Neurochem. Int. 2005a;47:449–457. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2005.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo J. Shi R. Acrolein induces axolemmal disruption, oxidative stress, and mitochondrial impairment in spinal cord tissue. Neurochem. Int. 2004;44:475–486. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2003.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo J. Shi R. Acrolein induces oxidative stress in brain mitochondria. Neurochem. Int. 2005;46:243–252. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2004.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo J. Uchida K. Shi R. Accumulation of acrolein-protein adducts after traumatic spinal cord injury. Neurochem. Res. 2005b;30:291–295. doi: 10.1007/s11064-005-2602-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLennan H.R. Degli Esposti M. The contribution of mitochondrial respiratory complexes to the production of reactive oxygen species. J. Bioenerg. Biomembr. 2000;32:153–162. doi: 10.1023/a:1005507913372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navarro A. Boveris A. The mitochondrial energy transduction system and the aging process. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2007;292:C670–C686. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00213.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nunomura A. Moreira P.I. Lee H.G. Zhu X. Castellani R.J. Smith M.A. Perry G. Neuronal death and survival under oxidative stress in Alzheimer and Parkinson diseases. CNS Neurol. Disord. Drug Targets. 2007;6:411–423. doi: 10.2174/187152707783399201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker W.D., Jr. Haas R. Stumpf D.A. Parks J. Eguren L.A. Jackson C. Brain mitochondrial metabolism in experimental thiamine deficiency. Neurology. 1984;34:1477–1481. doi: 10.1212/wnl.34.11.1477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Pinzon M.A. Dave K.R. Raval A.P. Role of reactive oxygen species and protein kinase C in ischemic tolerance in the brain. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2005;7:1150–1157. doi: 10.1089/ars.2005.7.1150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen D.R. Doorn J.A. Reactions of 4-hydroxynonenal with proteins and cellular targets. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2004;37:937–945. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2004.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Picklo M.J. Amarnath V. McIntyre J.O. Graham D.G. Montine T.J. 4-Hydroxy-2(E)-nonenal inhibits CNS mitochondrial respiration at multiple sites. J. Neurochem. 1999;72:1617–1624. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1999.721617.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Picklo M.J. Montine T.J. Acrolein inhibits respiration in isolated brain mitochondria. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2001;1535:145–152. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4439(00)00093-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sayre L.M. Perry G. Smith M.A. Oxidative stress and neurotoxicity. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2008;21:172–188. doi: 10.1021/tx700210j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sims N.R. Anderson M.F. Hobbs L.M. Kong J.Y. Phillips S. Powell J.A. Zaidan E. Impairment of brain mitochondrial function by hydrogen peroxide. Brain Res. Mol. Brain Res. 2000;77:176–184. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(00)00049-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh I.N. Sullivan P.G. Deng Y. Mbye L.H. Hall E.D. Time course of post-traumatic mitochondrial oxidative damage and dysfunction in a mouse model of focal traumatic brain injury: implications for neuroprotective therapy. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2006;26:1407–1418. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh I.N. Sullivan P.G. Hall E.D. Peroxynitrite-mediated oxidative damage to brain mitochondria: Protective effects of peroxynitrite scavengers. J. Neurosci. Res. 2007;85:2216–2223. doi: 10.1002/jnr.21360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens J.F. Maier C.S. Acrolein: sources, metabolism, and biomolecular interactions relevant to human health and disease. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2008;52:7–25. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.200700412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan P.G. Brown M.R. Mitochondrial aging and dysfunction in Alzheimer's disease. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry. 2005;29:407–410. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2004.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan P.G. Krishnamurthy S. Patel S.P. Pandya J.D. Rabchevsky A.G. Temporal characterization of mitochondrial bioenergetics after spinal cord injury. J. Neurotrauma. 2007;24:991–999. doi: 10.1089/neu.2006.0242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan P.G. Rabchevsky A.G. Keller J.N. Lovell M. Sodhi A. Hart R.P. Scheff S.W. Intrinsic differences in brain and spinal cord mitochondria: Implication for therapeutic interventions. J. Comp. Neurol. 2004;474:524–534. doi: 10.1002/cne.20130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szabo C. Ischiropoulos H. Radi R. Peroxynitrite: biochemistry, pathophysiology and development of therapeutics. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2007;6:662–680. doi: 10.1038/nrd2222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turrens J.F. Boveris A. Generation of superoxide anion by the NADH dehydrogenase of bovine heart mitochondria. Biochem. J. 1980;191:421–427. doi: 10.1042/bj1910421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiong Y. Hall E.D. Pharmacological evidence for a role of peroxynitrite in the pathophysiology of spinal cord injury. Exp. Neurol. 2009;216:105–114. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2008.11.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiong Y. Rabchevsky A.G. Hall E.D. Role of peroxynitrite in secondary oxidative damage after spinal cord injury. J. Neurochem. 2007;100:639–649. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.04312.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiong Y. Singh I.N. Hall E.D. Tempol protection of spinal cord mitochondria from peroxynitrite-induced oxidative damage. Free Radic. Res. 2009;43:604–612. doi: 10.1080/10715760902977432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]