Abstract

We conducted a meta-analysis of genome-wide association data to detect genes influencing age at menarche in 17,510 women. The strongest signal was at 9q31.2 (P = 1.7 × 10−9), where the nearest genes include TMEM38B, FKTN, FSD1L, TAL2 and ZNF462. The next best signal was near the LIN28B gene (rs7759938; P = 7.0 × 10−9), which also influences adult height. We provide the first evidence for common genetic variants influencing female sexual maturation.

Menarche is the start of menstruation and occurs at a mean age of approximately 13 years, normally about 2 years after the onset of puberty1. Twin and family studies suggest a significant genetic component to menarcheal age, with at least 50% heritability2–4. Linkage and candidate gene studies have not confirmed any loci that influence normal variation in age at menarche4,5. Genome-wide association (GWA) studies have been successful in identifying many variants associated with complex disease and quantitative traits and we therefore used this approach to identify genes involved in determining age at menarche. As earlier age at menarche is associated with shorter stature and obesity, the identified variants may not only clarify the genetic control of female sexual maturation but may also point to regulatory mechanisms involved in normal human growth and obesity.

We carried out a meta-analysis of 17,510 females from eight different population-based cohorts: Age/Gene Environment Susceptibility-Reykjavik Study (AGES-Reykjavik), Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study, Framingham Heart Study (FHS), Amish HAPI Heart Study, InCHIANTI Study, Rotterdam Study I and II and TWINS UK Study (Supplementary Note online). Women of European descent, with self-reported age at menarche between 9 and 17 years (representing the 1st to 99th percentile, with mean age at menarche of 13.12 (s.d. 1.5) years), were included. Agreement between adult-recalled and prospectively collected age at menarche is reported to be good (κ statistic = 0.81)6. Each study conducted a GWA analysis using linear regression or linear mixed-effects models with an additive genetic model adjusting for birth year or birth cohort (FHS), with additional adjustments for population structure when appropriate. Approximately 2.55 million autosomal SNPs, imputed with reference to the HapMap CEU panel, passed quality control criteria. We then conducted a meta-analysis using a fixed-effects model based on inverse variance weighting. Full details of cohorts and methods are given in Supplementary Table 1 and Supplementary Methods online.

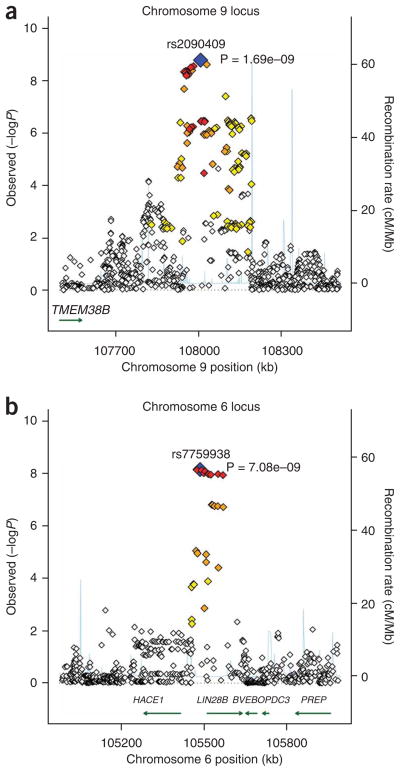

Twenty-eight SNPs passed the conventional genome-wide significance threshold of P < 5 × 10−8 and were at either 9q31.2 or 6q21 (Supplementary Table 2 and Supplementary Fig. 1 online). The 18 SNPs on chromosome 9 were in linkage disequilibrium (LD), with r2 > 0.31, as were the 10 SNPs on chromosome 6, with r2 > 0.96 (Fig. 1 and Supplementary Table 2). To identify more than one signal that could account for the association findings, we carried out conditional analysis adjusting for the SNP with the lowest P value in the region (rs7759938 for chromosome 6 and rs2090409 for chromosome 9). Within 1 Mb flanking each SNP, the lowest adjusted P values for association with age at menarche were P = 0.0017 and P = 0.0077 for chromosomes 9 (1,030 SNPs) and 6 (775 SNPs), respectively. These findings suggest a single signal accounting for the associations at each locus. The quantile-quantile plot (Supplementary Fig. 2 online) showed modest deviation away from the null when these top two signals were removed, suggesting the presence of additional loci for this trait.

Figure 1.

Genomic context (based on NCBI B36) of the top two independent signals at 9q31.2 and 6q21 plotted against association −log10 P values. Only UCSC Refseq genes are shown. r2 between each SNP and the top signal is color coded:> 0.8, red; 0.5–0.8, orange; 0.2–0.5, yellow; < 0.2, unfilled. Blue represents SNP with lowest P value. Chromosome positions are based on build hg18.

The strongest signal at 9q31.2 was observed with rs2090409, where each A allele was associated with approximately a 5-week reduction in menarcheal age (P = 1.7 × 10−9). All studies showed consistent evidence of association with the same direction of effect in all but one study, similar effect sizes and P values between 0.8 and 0.0003 (Table 1). The recombination region containing rs2090409 includes only a hypothetical gene (BC039487). Outside of this, the only RefSeq gene within a 1-Mb window is a transmembrane protein gene, TMEM38B, which is approximately 400 kb proximal to the GWAS signal. In mice, TMEM38B is expressed strongly in brain and the null mutation is neonatal lethal. Within 2 Mb of the signal, genes include SLC44A1, FKTN, FSD1L, TAL2 and ZNF462, none of which is an obvious candidate gene for involvement in menarche. However, a SNP in ZNF462, 650 kb from our signal but not in LD (r2 = 0.086), has been previously associated with variation in height6.

Table 1.

Genome-wide significant associations with age at menarche

| SNP | Study | N | Allele | Frequency | Imputation quality | Effect (years) | s.e. | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rs2090409 | ARIC | 4,247 | A | 0.31 | 1.00 | −0.10 | 0.04 | 0.004 |

| FHS | 3,801 | A | 0.31 | 0.99 | −0.07 | 0.04 | 0.07 | |

| RSI | 3,175 | A | 0.34 | 1.01 | −0.08 | 0.04 | 0.06 | |

| TwinsUK | 2,276 | A | 0.32 | 0.99 | −0.11 | 0.03 | 0.0003 | |

| AGES-Reykjavik | 1,849 | A | 0.27 | 0.99 | −0.08 | 0.05 | 0.09 | |

| RSII | 1,000 | A | 0.35 | 1.06 | −0.15 | 0.07 | 0.04 | |

| InCHIANTI | 597 | A | 0.33 | 0.98 | −0.26 | 0.09 | 0.005 | |

| HAPI Heart Study | 565 | A | 0.28 | 0.95 | 0.03 | 0.10 | 0.7809 | |

| Meta-analysis | 17,510 | A | 0.31 | 1.00 | −0.10 | 0.02 | 1.7 × 10−9 | |

| rs7759938 | ARIC | 4,247 | C | 0.33 | 0.94 | 0.12 | 0.04 | 0.001 |

| FHS | 3,801 | C | 0.33 | 0.90 | 0.10 | 0.04 | 0.009 | |

| RSI | 3,175 | C | 0.31 | 1.00 | 0.06 | 0.04 | 0.16 | |

| TwinsUK | 2,276 | C | 0.32 | 0.98 | 0.06 | 0.03 | 0.04 | |

| AGES-Reykjavik | 1,849 | C | 0.34 | 1.00 | 0.08 | 0.04 | 0.07 | |

| RSII | 1,000 | C | 0.30 | 0.94 | 0.09 | 0.08 | 0.27 | |

| InCHIANTI | 597 | C | 0.29 | 0.98 | 0.24 | 0.09 | 0.008 | |

| HAPI Heart Study | 565 | C | 0.23 | 0.91 | 0.34 | 0.11 | 0.002 | |

| Meta-analysis | 17,510 | C | 0.33 | 0.96 | 0.09 | 0.02 | 7.0 × 10−9 |

Meta-analysis P values are corrected by individual-study genomic control inflation factors. Alleles are based on forward strand and positions on NCBI build 36. Meta-analysis frequency is calculated as weighted average across all studies. Imputation quality refers to the imputation quality score generated by MACH (oevar)/SNPTEST (proper_info).

The 6q21 signal was within a recombination interval that included only one gene, LIN28B (Fig. 1) and was also associated with approximately a 5-week reduction in menarcheal age per T allele (rs7759938; P = 7.0 × 10−9). The effect was consistent across all studies, with P values between 0.27 and 0.001 (Table 1). A common variant in the LIN28B gene has previously been associated with normal variation in adult height7. The most significant menarche-associated variant (rs7759938) and the previously reported height variant (rs314277) lie within 28.7 kb of each other and are likely to represent the same signal, as r2 = 0.26 and D′ = 1 in HapMap. The allele associated with earlier age at menarche is associated with decreased height, which is consistent with epidemiological data. Early menarche has been correlated with reduced stature, and the mechanism is probably mediated through earlier exposure to estrogens resulting in earlier closure of the epiphyseal plates8. We therefore tested all published common variants influencing height—44 independent loci—for association with age at menarche in our dataset9. Six of the alleles were also associated with menarcheal age (P < 0.05), with the strongest associations at LIN28B (P = 0.0001) and PXMP3 (P = 0.003) (Supplementary Table 3 online). We also tested the association of the newly identified menarche-associated variant, rs7759938, with measured height in our study population (Supplementary Methods) and found that it was associated with height, Pmeta = 0.0001, in the same direction in all but one study; that is, the C allele was associated with reduction in age at menarche and also reduced stature. The published height SNP (rs314277) did not reach nominal significance with height in our study (Pmeta = 0.26). These data suggest that some of the previously identified loci that influence adult height may also have a general role in adolescent growth.

At a given chronologic age, girls with earlier age at menarche tend to have greater body mass index (BMI) and adiposity than girls with a later age at menarche10–12. A marked secular decline in age at menarche occurred in Europe in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, which has been attributed to improved nutrition and health1. This trend may be continuing as a consequence of the obesity epidemic13 and may involve a common metabolic response to the current nutritional environment14 or be attributable, at least in part, to shared genetic influences or pleiotropy15. We therefore investigated the effect on menarcheal age of the ten currently known common gene variants associated with variation in BMI. Of these ten loci, eight showed an association in the direction consistent with epidemiological data (P = 1.6 × 10−6, based on Fisher’s combined probability test: −2 × sum(ln P) against χ2 on (10 × 2) df), and five were nominally significant (P < 0.05) (Supplementary Table 4 online). The two loci with the largest observed effects on BMI (FTO and TMEM18) also had the strongest evidence for association with menarcheal age (P = 0.0008 and 7.0 × 10−5, respectively).

This study provides the first evidence for common genetic variants influencing normal variation in the timing of female sexual maturation. Our findings also indicate a genetic basis for the phenotypic associations between age at menarche and both height and BMI.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are indebted to the participants and staff of the studies for their important contributions. Full individual study acknowledgements are listed in the Supplementary Methods.

Footnotes

Note: Supplementary information is available on the Nature Genetics website.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Statistical analyses: J.R.B.P., L.S., N.F., K.L.L., G.Z., P.F.M., A.V.S., T.A., K.E., V.G., F.R., N.S., T.T., M.N.W. and V.Z. Sample collection, preparation: N.F., A.V.S., T.A., S.B., E.B., L.C., G.E., L.F., A.R.F., V.G., A.H., S.G.W., T.B.H., T.D.S., E.W.D. and A.G.U. Genotyping: E.B., F.R., A.S., N.S. and A.G.U. Manuscript writing: J.R.B.P., L.S., P.F.M., A.V.S., T.A., G.E., V.G., E.A.S., A.M., E.W.D. and A.G.U. Review and revision of the manuscript: J.R.B.P., L.S., N.F., K.L.L., G.Z., P.F.M., A.V.S., T.A., S.B., E.B., L.C., G.E., K.E., L.F., A.R.F., M.G., V.G., A.H., D.K., D.P.K., L.J.L., J.v.M., M.A.N., F.R., A.R.S., A.S., N.S., T.T., J.A.V., M.N.W., S.G.W., V.Z., E.A.S., T.B.H., A.M., T.D.S., E.W.D., A.G.U. and J.M.M. Intellectual input: J.R.B.P., L.S., N.F., K.L.L., P.F.M., E.B., G.E., A.R.F., V.G., D.K., D.P.K., J.A.V., S.G.W., A.M., A.G.U. and J.M.M. Study design: J.R.B.P., L.S., K.L.L., G.Z., A.V.S., T.A., S.B., G.E., L.F., V.G., A.H., D.K., D.P.K., A.M., T.D.S., A.G.U. and J.M.M.

Reprints and permissions information is available online at http://npg.nature.com/reprintsandpermissions/

References

- 1.Marshall WA, Tanner JM. Arch Dis Child. 1969;44:291–303. doi: 10.1136/adc.44.235.291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Towne B, et al. Am J Phys Anthropol. 2005;128:210–219. doi: 10.1002/ajpa.20106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Snieder H, MacGregor AJ, Spector TD. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1998;83:1875–1880. doi: 10.1210/jcem.83.6.4890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Anderson CA, et al. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93:3965–3970. doi: 10.1210/jc.2007-2568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gajdos ZKZ, et al. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93:4290–4298. doi: 10.1210/jc.2008-0981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bosetti C, Tavani A, Negri E, Trichopoulos D, La Vecchia C. J Clin Epidemiol. 2001;54:902–906. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(01)00362-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lettre G, et al. Nat Genet. 2008;40:584–591. doi: 10.1038/ng.125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Onland-Moret NC, et al. Am J Epidemiol. 2005;162:623–632. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwi260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Weedon MN, Frayling TM. Trends Genet. 2008;24:595–603. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2008.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Anderson SE, Dallal GE, Must A. Pediatrics. 2003;111:844–850. doi: 10.1542/peds.111.4.844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Garn S, LaVelle M, Rosenberg K, Hawthorne V. Am J Clin Nutr. 1986;43:879–883. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/43.6.879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.van Lenthe F, Kemper C, van Mechelen W. Am J Clin Nutr. 1996;64:18–24. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/64.1.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Euling SY, et al. Pediatrics. 2008;121:S172–S191. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-1813D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Harris MA, Prior JC, Koehoorn M. J Adolesc Health. 2008;43:548–554. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2008.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang W, Zhao LJ, Liu YZ, Recker RR, Deng HW. Int J Obes (Lond) 2006;30:1595–1600. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.