Abstract

Background

Prior demonstrations of impaired attentional control in schizophrenia focused on conditions in which top-down control is needed to overcome prepotent response tendencies. Attentional control over stimulus processing has received little investigation. Here we test whether attentional control is impaired during working memory encoding when salient distractors compete with less salient task-relevant stimuli.

Methods

Patients with schizophrenia (n=28) and healthy controls (HC, n=25) performed a visuospatial working memory paradigm in which half of the to-be-encoded stimuli flickered to increase their salience. After a 2-s delay, stimuli reappeared and participants had to decide whether or not a probed item had shifted location.

Results

In the Unbiased condition where flickering and non-flickering stimuli were equally likely to be probed, both groups displayed a trend towards better mesmory for the flickering items. In the Flicker-bias condition in which the flickering stimuli were likely to be probed, both groups displayed a robust selection advantage for the flickering items. However, in the Nonflicker-bias condition in which the non-flickering stimuli were likely to be probed, only HC showed selection of the non-flickering items. Patients displayed a trend toward preferential memory for the flickering items, as in the unbiased condition.

Conclusions

Both groups were able to select salient over non-salient stimuli, but patients with schizophrenia were unable to select non-salient over salient stimuli, consistent with impairment in the effortful control of attention. These findings demonstrate the generality of top-down control failure in schizophrenia in the face of bottom-up competition from salient stimuli as with prepotent response tendencies.

Keywords: schizophrenia, selective attention, distraction, bottom-up, top-down, working memory

Introduction

Abnormalities of attention have long been thought to be a central feature of schizophrenia. The general function of attention is to provide a competitive advantage when multiple sensory inputs, thoughts, or action plans compete with each other for access to the limited resources of neural representation, awareness, and motor production (1). Basic cognitive neuroscience demonstrates that the brain implements attentional functions by means of a large network of partially independent subsystems (2,3). Thus, one of the major challenges facing the field is to specify which types of attentional mechanisms are impaired in people with schizophrenia (PSZ) and which may be spared (4).

Some types of stimuli or response tendencies have an intrinsic competitive processing advantage and will tend to dominate behavior. For example, high-salience stimuli have a bottom-up processing advantage over low-salience stimuli (5), and high-probability and automatized responses have an advantage over low-probability and less automatic responses (6). Attentional control systems are challenged when the less potent stimulus or response tendency is task-appropriate and strong top-down bias signals are necessary to overcome the more potent stimulus or response (7). Thus, impairments in attentional control may be apparent primarily under conditions in which high-potency stimuli or responses must be suppressed.

Indeed, the most persuasive evidence of impaired attentional control in PSZ has been obtained in tasks that emphasize competition between low-potency correct responses and high-potency incorrect responses. For example, deficits have frequently been documented in “context” versions of the CPT (8), in the Stroop interference condition (9), and in anti-saccade tasks (10,11). In each of these cases, top-down control is needed to inhibit a prepotent response tendency, whether this response has achieved prepotency through task contingencies (context CPT), from pre-experimental experience (Stroop), or through the reflexivity of eye movements towards sudden-onset stimuli (anti-saccade paradigm).

In the basic science literature, most studies of selective attention focus on the selective processing of competing inputs rather than on resolving response competition. However, most of the evidence for impaired attentional control in PSZ has been obtained in tasks that emphasize response selection. There is a paucity of evidence that top-down control processes function abnormally in the selective encoding of visual inputs for further perceptual processing or working memory (WM) storage (for suggestive evidence concerning auditory selective attention see 12,13). This may indicate that attentional dysfunction in schizophrenia primarily impacts output-related rather than input-related processes. Alternatively, this lack of evidence may originate from the fact that studies of input selection in PSZ have not typically used tasks in which a low-potency input must be selected in the face of competition from a high-potency input.

Consider, for example, the Posner orienting paradigm (14), in which a cue indicates that attention should be directed to a specific location, and the effectiveness of attentional selection is assessed by comparing performance for targets presented at the cued versus uncued location. With few exceptions (15,16), attentional control processes are minimally challenged in this paradigm because there is no need to actively ignore irrelevant stimuli. Accordingly, the overall effectiveness of attentional selection is not found to be impaired in schizophrenia. That is, despite overall slowed responding, the difference between valid and invalid trials is not reduced in PSZ as compared with HC, indicating that PSZ are able to select spatial locations based on the cue information (reviewed by 17).

Similarly, no evidence for impaired attentional selection in PSZ was obtained when cues were used to indicate which stimuli should be encoded into visual WM (18). In four separate experiments, equal numbers of relevant and irrelevant stimuli were presented, and subjects were instructed to remember, for example, the colors of the circles and not the colors of the rectangles. The selection criteria never changed between trials, cues were always simple and salient (shape, color, location), and cued and uncued items were of similar bottom-up salience. Thus, selection of relevant items may have required only a modest boost from top-down bias signals. Accordingly, patients showed robust storage of relevant items and minimal encoding of irrelevant distractors, that is, no evidence of impaired attentional selection.

The present study was designed to test whether PSZ would exhibit specific impairment in attentional selection for WM encoding when control aspects of attentional selection were challenged by irrelevant stimuli holding a competitive salience advantage relative to the relevant stimuli. A deficit, if observed under these conditions, would demonstrate that schizophrenia involves a general deficit in overcoming competition at both encoding and response stages rather than a limited impairment at the stage of response selection.

Methods and Materials

Participants

Twenty-eight patients meeting Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-IV (DSM-IV; 19) criteria for schizophrenia (N=13 paranoid, 7 undifferentiated, 2 residual) or schizoaffective disorder (N=6), and 25 matched healthy control subjects (HC) participated in this study. Diagnosis was established using a best estimate approach in which information from a Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID) was combined with a review of patient medical records at a consensus diagnosis meeting chaired by one of the authors (JG). Demographic information is summarized in Table 1. Groups did not differ in age [t(51)=0.62, P>0.5], parental education [t(48)=0.82, P>0.4], sex (Chi-square P>0.9) or ethnicity (Chi-square P>0.24). However, patients had significantly fewer years of education than controls [t(51)=3.46, P<0.01].

Table 1.

Group Demographics

| Patients | Controls | |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 41.7 ± 9.0 (range 22–53) | 43.2 ± 8.8 (range 25–56) |

| Male: Female | 15: 13 | 13: 12 |

| AA: A: C: Oa | 11: 0: 14: 3 | 11: 0: 14: 0 |

| Education (years) | 13.1 ± 2.0 | 14.9 ± 1.8* |

| Parental educationb | 14.3 ± 3.1c | 13.6 ± 2.1 |

| WASI | 100.2 ± 14.4d | 113.1 ± 11.4** |

| WRAT 4 standard score | 98.7 ± 14.7d | 100.6 ± 14.7 |

| WTAR standard score | 101.4 ± 16.4d | 104.2 ± 13.2 |

| MATRICS total score | 33.3 ± 15.4d | 49.3 ± 10.7** |

AA = African American; A = Asian; C = Caucasian; O = Other

average over mother’s and father’s years of education

data unavailable for 3 subjects

data unavailable for 1 subject

P<0.01,

P<0.001; significant difference between PSZ and HC in independent samples t-test

The patients were clinically stable outpatients. At the time of testing, patients obtained a total score of 36.1±7.3 (mean ± stdev) on the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (range 24–53; 20), 36.0±14.3 on the Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms (range 4–73; 21), 20.9±6.3 on the Level Of Functioning Scale (range 11–34, 22), and 2.5±2.4 on the Calgary Depression Scale (range 0–9; 23). All patients were receiving antipsychotic medication at time of testing; 4 were treated with first-generation antipsychotics, 22 with second-generation antipsychotics, and 2 with both. Fourteen patients additionally received mood stabilizing medication, 5 anxiolytic and 3 antiparkinsonian medication. Medication had not changed in the preceding four weeks. Control participants were recruited from the community via random digit dialing and word of mouth and had no Axis 1 or 2 diagnoses as established by a SCID, had no self-reported family history of psychosis, and were not taking any psychotropic medication. Participants provided informed consent for a protocol approved by the University of Maryland School of Medicine Institutional Review Board. Before participants signed the consent form, the investigator reviewed its content with the volunteer and answered any questions. Before volunteers with schizophrenia signed the consent form, the investigator, in the presence of a third-party witness, also formally evaluated basic understanding of study demands, risks, and what to do if experiencing distress or to end participation.

Neuropsychological testing

Participants completed the Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence (WASI; 24), the Wide Range Achievement Test Reading (WRAT 4; 25), the Wechsler Test of Adult Reading (WTAR; 26), and the MATRICS battery (27). Neuropsychological testing was usually performed on a separate day to avoid fatigue. PSZ scored lower than HC on the WASI (P<0.001, independent-samples t-test) and MATRICS battery (P<0.001), and exhibited significant impairment in all MATRICS domains except Visual Learning. There were no group differences on the WRAT 4 (P>0.6) or WTAR (P>0.5), suggesting similar premorbid functioning in the two groups (see Table 1).

Stimuli

The task was presented in a dimly illuminated room (1.0 FC) on a 17″ CRT monitor with a 60 Hz refresh rate. Stimuli were presented against a grey background (luminance approximately 22 cd/m2). A white fixation cross was presented in the center of the screen throughout each task trial until the trial was ended by a response.

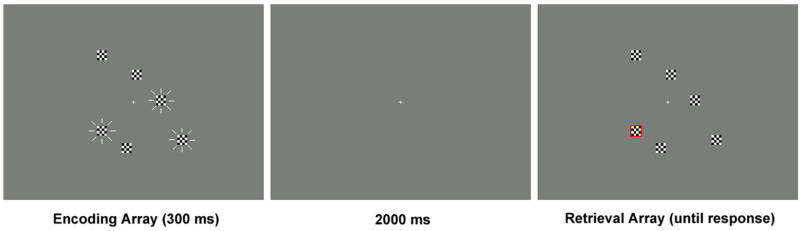

Figure 1 illustrates the sequence of events in each task trial. Each trial started with a 300-ms presentation of six black-and-white checked (4×4) squares, each subtending 0.98° of visual angle (encoding array). For three of these squares, the black and white checks reversed (in phase across all three squares) at a frequency of 7.5 Hz during the 300-ms stimulus presentation, creating the appearance of flickering. After a 2000-ms delay, all squares reappeared (retrieval array). This time none of them flickered. One square was outlined by a red frame (the probed item). The task consisted of making a forced choice response on one of two buttons to indicate whether the probed item was in exactly the same position as in the encoding array, or if it had shifted slightly (by 1.6°) in any direction. On half the trials, the probed item changed position; on the other half it stayed in the same position. The critical comparison was of memory performance on trials in which the probed stimulus was one of the three items that had been flickering during encoding and trials in which the probed stimulus had not been flickering. The retrieval array stayed on the display until a response was made, followed by a 1-s intertrial interval during which the screen was blank.

Figure 1.

An example of the stimulus displays during a task trial. In the encoding array, three randomly chosen squares, indicated here by radiating lines, flickered as described in the Methods.

There were three task conditions. The “Unbiased” condition was always run first to avoid any prior attention instructions carrying over and preventing a truly unbiased attentional focus. Here, flickering and non-flickering items were probed with equal probability in a random sequence. This condition consisted of 80 trials, split into two blocks that were separated by a rest period. The “Flicker-bias” and “Nonflicker-bias” conditions were run next, in counterbalanced order. Both of these bias conditions consisted of 200 trials, split into five blocks that were separated by rest periods. In the Flicker-bias condition, a previously flickering item was probed on 80% of trials and a previously non-flickering item on only 20% of trials. In the Nonflicker-bias condition, a previously flickering item was probed on 20% of trials, and a previously non-flickering item on 80% of trials. In the biased conditions, participants were instructed that either a flickering or a non-flickering item would be probed “most of the time”.

In total, the task consisted of 480 trials and, including breaks, took approximately 60 minutes to complete. Some participants completed the three task conditions on different days, to avoid fatigue.

Data analysis

Performance data were converted to Cowan’s K (28), a measure of the number of items encoded in short-term memory that is more linearly related to the amount of information available than the percentage of correct responses. Conversions were performed by the following procedure: responding “change” to a change trial was considered a hit; responding “no change” to a no-change trial was considered a correct rejection; responding “change” to a no-change trial was considered a false alarm; and responding “no change” to a change trial was considered a miss. Based on these values, the hit rate [hits/(hits + misses)] and false alarm rate [false alarms/(false alarms + correct rejections)] were calculated. Hit and false alarm rates are presented in Table S1 (see Supplement 1). K was derived by subtracting the false alarm rate from the hit rate, and multiplying the result by the number of items in the tested set. This was done separately for trials in which memory was tested for a flickering versus non-flickering item to obtain separate measures of the number of flickering items and the number of non-flickering items that were stored in memory. Consequently, there were three items in the set that was tested on a given trial.

K values were analyzed by a three-factor ANOVA with GROUP (PSZ vs. HC) as a between-subject factor and TASK (Unbiased, Flicker-bias, Nonflicker-bias) and STIMULUS (flickering vs. non-flickering during encoding) as within-subject factors. A significant three-way interaction was followed up by two-factor ANOVA and paired t-tests. An analysis of the order of the Flicker-bias and Nonflicker-bias conditions is described in Supplement 1. The order of testing did not differentially affect the attentional bias effect in the two conditions or groups. Thus, carry-over effects cannot explain the observed pattern of effects.

To test whether the ability to select task-relevant stimuli is related to WM capacity, we correlated each individual’s attentional selection effect in both biased conditions (Flicker-bias: K for flickering minus non-flickering stimuli; Nonflicker-bias: K for non-flickering minus flickering stimuli) with K scores derived from an independent WM task to ensure measurement independence from the attentional bias scores. This was a 60-trial change localization task, using the method of Gold et al. (Experiment 5 in reference 18). Participants viewed an array of four colored squares, arranged around a central cross, for 100 ms (Figure S1 in Supplement 1). After a 900 ms delay, the four squares reappeared. The task was to mouse-click on the one square that had changed color.

Results

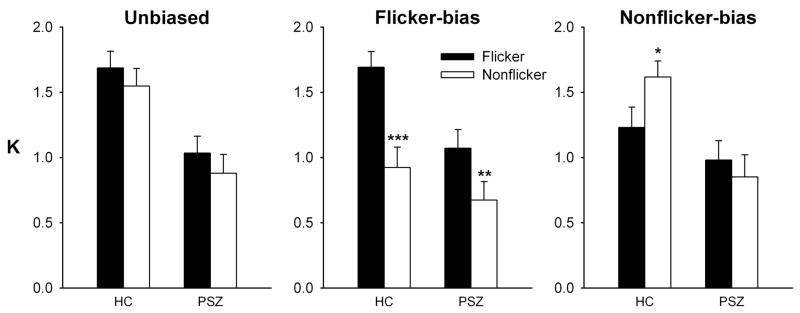

Figure 2 shows K values for HC and PSZ. The three graphs detail performance when flickering and non-flickering squares were probed with equal likelihood (Unbiased), or when it was more likely that a flickering square (Flicker-bias) or a non-flickering square (Nonflicker-bias) would be probed. In the Unbiased condition, there was a slight competitive advantage for the flickering stimuli in both subject groups. Performance differed greatly between flickering and non-flickering items in the two bias conditions. In the Flicker-bias condition, both groups displayed greater accuracy for the flickering items. In the Nonflicker-bias condition, HC displayed greater accuracy for non-flickering items, while no such effect was seen in PSZ.

Figure 2.

The number of flickering (“Flicker”) or non-flickering (“Nonflicker”) task stimuli represented in working memory (K) in the three different task conditions. In the Unbiased condition, items that had been flickering or non-flickering during encoding were equally likely to be cued. In the Flicker-bias condition, an item that had been flickering during encoding was probed 80% of the time. In the Nonflicker-bias condition, a previously non-flickering item was probed 80% of the time. The graphs represent averages (±SEM) over 28 people with schizophrenia (PSZ) and 25 healthy control participants (HC). Significant differences between flickering and non-flickering stimuli are marked: * P<0.05, ** P<0.01, *** P<0.001, paired t-tests.

In the ANOVA, a main effect of GROUP [F(1,51)=10.2, P=0.002] reflected lower performance in PSZ across task conditions. A significant GROUP × STIMULUS × TASK interaction [F(2,102)=6.48, P=0.002] confirmed that the effects of stimulus type depended on the task condition, but differently so in the two subject groups. The three-way interaction was followed up with two-factor ANOVA (GROUP × STIMULUS) in each task condition. In the Unbiased condition, there was a trend towards greater accuracy for flickering than non-flickering stimuli [STIMULUS main effect: F(1,51)=3.89, P=0.054], but no STIMULUS × GROUP interaction (P>0.9). In the Flicker-bias condition, the effects of STIMULUS interacted with GROUP [F(1,51)=4.17, P<0.05], suggesting that although both groups performed significantly better with the flickering stimuli, this effect was more pronounced in HC (P<0.001, paired t-test) than PSZ (P=0.002). The Nonflicker-bias condition yielded an even stronger STIMULUS × GROUP interaction [F(1,51)=7.30, P<0.01], reflecting a significant performance advantage for the non-flickering stimuli in HC (P<0.02), but if anything, a trend in the opposite direction in PSZ, mimicking performance in the Unbiased condition.

It is interesting to note that the effect of attention in this task consisted entirely of the suppression of distractors. That is, K for the attended stimulus type in the biased conditions always was similar to the Unbiased condition, but there were performance costs for the unattended stimulus type relative to the Unbiased condition. Statistically, K for the non-flickering stimuli was significantly lower in the Flicker-bias than Unbiased condition for both HC (P<0.001) and PSZ (P=0.036), and K for the flickering stimuli was significantly lower in the Nonflicker-bias than Unbiased condition for HC (P=0.013). However, this effect was absent in PSZ (P>0.6). Thus, while both groups were able to bias their attention away from the non-flickering items when a flickering item was likely to be probed, HC but not PSZ were able to bias their attention away from the salient flickering stimuli when a non-flickering stimulus was likely to be probed.

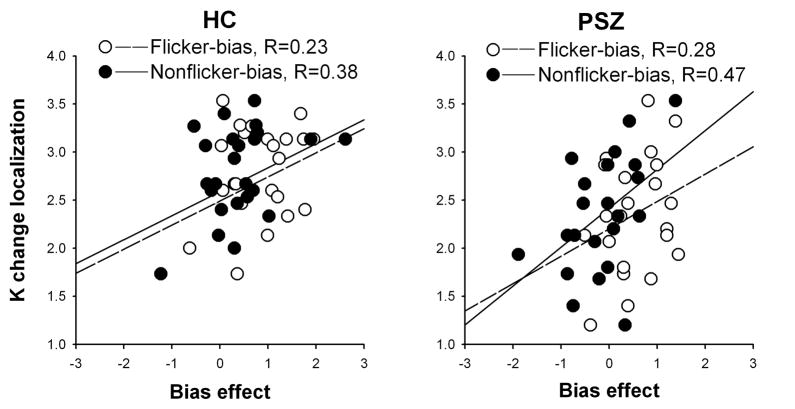

To test whether an individual’s ability to selectively encode the stimuli likely to be probed was related to WM capacity, we correlated the attentional bias effect in the two biased conditions (Flicker-bias: K for flickering minus non-flickering stimuli; Nonflicker-bias: K for non-flickering minus flickering stimuli) with K scores derived from an independent measure of visual WM capacity (from a change localization task). Due to color-blindness, this task was not performed by one HC and six PSZ, resulting in n=24 and n=22, respectively. With data collapsed across both groups, WM capacity correlated with the attentional bias effect in both the Flicker-bias (R=0.30, P<0.05) and Nonflicker-bias condition (R=0.50, P<0.001), but the correlation was significantly greater in the Nonflicker-bias conditions (Fisher’s z-transformation test for difference in correlation: z=2.23, P<0.05). The same correlations were inspected in each group individually. Although none of the correlations differed significantly between groups, the difference between the Flicker- and Nonflicker-bias condition correlations appeared to be mostly fueled by the patient group. Whereas correlations in HC were non-significant in both the Flicker-bias (R=0.23, P>0.2) and Nonflicker-bias conditions (R=0.38, P=0.07), PSZ displayed a similarly low correlation in the Flicker-bias condition (R=0.28, P>0.2), but a more robust correlation in the Nonflicker-bias condition (R=0.47, P<0.05, Figure 3). These trends suggest that the degree to which patients are unable to select non-salient over salient stimuli is related to their degree of WM capacity reduction. We did not replicate this pattern of correlations with working memory indices derived from the MATRICS battery; performance of these tasks is heavily influenced by executive functioning and not likely to capture much variance related to capacity.

Figure 3.

Pearson correlations in people with schizophrenia (PSZ) and healthy control subjects (HC) between working memory capacity (K) in a change localization task and the attentional bias effect in the Flicker-bias (K for flickering minus non-flickering stimuli) and Nonflicker-bias (K for non-flickering minus flickering stimuli) conditions.

Discussion

The present study provided evidence for impaired attentional control of working memory encoding in schizophrenia under conditions of competition from salient distractor stimuli. While both PSZ and HC were able to select salient over non-salient stimuli, HC but not PSZ were able to select non-salient over salient stimuli. Thus, patients could efficiently implement selection when top-down control processes were bolstered by bottom-up stimuli that conferred a competitive salience advantage consistent with the top-down bias. However, selection failed when attention needed to be biased away from stimuli that had a bottom-up advantage conflicting with the top-down goals. These results extend prior observations of attentional control failures at the stage of response selection (see Introduction) and add to previous indications that deficits in the control of input selection are present in schizophrenia (15,16,29,30,31). In other words, PSZ have difficulty inhibiting not only prepotent response tendencies but also salient perceptual inputs.

At first sight, there was a group difference in attentional selection not only in the Nonflicker-bias, but also in the Flicker-bias condition, such that PSZ displayed a smaller net benefit in K for attending the flickering over non-flickering stimuli. Thus, the selection deficit may not be entirely selective for the Nonflicker-bias condition. However, when put into relation with each group’s overall performance in the Flicker-bias condition, the groups appeared to allocate a similar proportion of resources to the flickering items. To quantify this, we computed the percentage of the overall storage capacity that was devoted to the flickering versus the non-flickering items (K for flickering stimuli divided by the sum of K for flickering and non-flickering stimuli in the Flicker-bias condition). We found that 65% of capacity was devoted to the flickering items for HC vs. 61% for PSZ. Thus, the two groups devoted an approximately equal proportion of their WM capacity to the flickering items in the Flicker-bias condition. In the Nonflicker-bias condition, in contrast, HC devoted 57% of capacity to the non-flickering items and PSZ 47% (i.e., patients devoted more capacity to the flickering items in this condition). Thus, the group difference in attentional selection was negligible in the Flicker-bias condition but substantial in the Nonflicker-bias condition. Unfortunately, it was not possible to perform a valid statistical analysis of these data because this sort of ratio measure leads to extreme outliers in the single-subject data when the denominator approaches zero.

The overall lower performance observed in PSZ is in agreement with substantial and consistent impairment in visuospatial WM (32,33). For example, difficulty of PSZ in maintaining precise visuospatial information in WM has been demonstrated (34). Thus, PSZ may be particularly challenged in the visuospatial domain. However, although the current task required that spatial information be encoded and maintained in WM, other physical stimulus properties (flickering) were used to define which items should be encoded. Thus, the observed selection deficits cannot be explained by deficits in the processing of visuospatial information. A possible group difference in perceptual processing that then needs to be considered is whether PSZ and HC perceived the flickering in the same way. The data show that the flickering was salient for both groups, as PSZ and HC both displayed the same trend towards better performance with flickering items in the Unbiased condition.

Participants were not instructed to maintain central fixation. Due to the short (300 ms) presentation of the encoding array, there was little time to incur large group differences in the systematic exploration of the array by overt eye-movements. PSZ may have displayed a greater tendency to make eye-movements to the salient flickering items they had difficulty ignoring, but this would have led to a general encoding advantage for these items relative to HC, which was not observed in the Unbiased or Flicker-bias conditions. Nevertheless, future studies should explore such questions by employing eye-tracking techniques. Furthermore, impaired configural processing may have caused less efficient perceptual grouping of flickering and non-flickering stimuli in PSZ than HC. Such grouping results in effectively fewer individual items to be processed and facilitates selection. The literature provides mixed evidence of a grouping deficit in schizophrenia (35,36,37,38,39,40,41). The divergence may reflect differences in sample composition because grouping deficits appear to be particularly prominent in patients with high levels of disorganization symptoms (42). Our sample did not include any patients with disorganized schizophrenia, and given that we studied stable outpatients, we encountered low levels of these symptoms. Thus, the present sample would not be expected to display prominent grouping deficits. Moreover, the use of in-phase flickering should have made grouping of the flickering stimuli trivially easy even for individuals with grouping deficits. Furthermore, a grouping deficit would have led to impaired performance in both the Flicker-bias and Nonflicker-bias conditions and could not explain the observed pattern of results.

The present findings also have implications about the nature of WM deficits in schizophrenia. Individuals differ in how much task-relevant information they can temporarily store when attention is diverted away from the perceptual input (43,44,45). In PSZ, reduced WM capacity is a particularly robust finding (46,47,48,49,50). Given that WM capacity is sharply limited, the appropriate selection of task-relevant information for consolidation is critical. There is evidence that individuals displaying low capacity tend to be less selective during encoding and store more irrelevant information than high-capacity individuals (51). Thus, poor WM may reflect a failure of attentional selection of only task relevant items rather than a reduction in storage capacity per se.

The present findings suggest that the reductions in measures of WM capacity found in schizophrenia may be due to deficits in selectively encoding task-relevant items when irrelevant items have a bottom-up salience advantage. Indeed, on an inter-individual level, the ability of PSZ to bias attention away from salient task stimuli was related to WM capacity derived from an independent task. This correlation mirrors findings on anti-saccade performance in healthy subjects (52) and suggests that, in schizophrenia, a reduced ability to prevent salient distractor stimuli from occupying available WM capacity may contribute to a lower capacity for task-relevant stimuli. While in the literature the finding of lower WM capacity is not restricted to task conditions with strong bottom-up competition, salient distractors may also originate from sources outside of the administered paradigm, such as the external environment or internal sources. For example, PSZ reportedly display hyperactivity during task-performance in brain regions that mediate task-independent thought, and this was suggested to reflect a misdirection of attentional resources to internal events (53).

The main finding of this study was that selection deficits in schizophrenia were particularly pronounced in, and limited to, conditions in which the top-down control of attentional resource allocation was particularly challenged by salient distractors. This specific selection deficit may partially explain lower WM capacity in schizophrenia, such that irrelevant but salient stimuli occupy storage space that could otherwise be used to hold relevant information. The present results also help settle a controversy that has recently emerged in the literature regarding whether or not PSZ display deficits in attentional selection. The present findings provide evidence that the basic mechanisms involved in implementing selection are preserved, as illustrated by the clear advantage in the recall of the high-salience stimuli when these were attended. However, attentional selection mechanisms fail when salient bottom-up competition creates high demands on top-down control over attentional resource allocation. The present findings demonstrate that this formulation of the nature of control deficits applies across different types of selection, including the selection of not only response but also perceptual input. That is, control fails in the face of strong bottom-up competition.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was made possible by a grant from the National Institute of Mental Health [grant number MH065034 to JMG and SJL]. We thank all volunteers participating in this study.

Footnotes

Financial Disclosures

The authors reported no biomedical financial interests or potential conflicts of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Luck SJ, Vecera SP. Attention. In: Yantis S, editor. Stevens’ Handbook of Experimental Psychology, Vol. 1: Sensation and Perception. 3. New York: Wiley; 2002. pp. 235–286. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Desimone R, Duncan J. Neural mechanisms of selective visual attention. Annu Rev Neurosci. 1995;18:193–222. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ne.18.030195.001205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Corbetta M, Shulman GL. Control of goal-directed and stimulus-driven attention in the brain. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2002;3:201–215. doi: 10.1038/nrn755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Luck SJ, Gold JM. The construct of attention in schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry. 2008;64:34–39. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.02.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Egeth HE, Yantis S. Visual attention: control, representation, and time course. Annu Rev Psychol. 1997;48:269–297. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.48.1.269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cohen JD, Dunbar K, McClelland JL. On the control of automatic processes: a parallel distributed processing account of the Stroop effect. Psychol Rev. 1990;97:332–361. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.97.3.332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schmidt BK, Vogel EK, Woodman GF, Luck SJ. Voluntary and involuntary attentional control of visual working memory. Percept Psychophys. 2002;64:754–763. doi: 10.3758/bf03194742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Servan-Schreiber D, Cohen JD, Steingard S. Schizophrenic deficits in the processing of context. A test of a theoretical model. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1996;53:1105–1112. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1996.01830120037008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hepp HH, Maier S, Hermle L, Spitzer M. The Stroop effect in schizophrenic patients. Schizophr Res. 1996;22:187–195. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(96)00080-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hutton SB, Ettinger U. The antisaccade task as a research tool in psychopathology: a critical review. Psychophysiology. 2006;43:302–313. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.2006.00403.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Radant AD, Dobie DJ, Calkins ME, Olincy A, Braff DL, Cadenhead KS, et al. Successful multi-site measurement of antisaccade performance deficits in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2007;89:320–329. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2006.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Oltmanns TF, Ohayon J, Neale JM. The effect of anti-psychotic medication and diagnostic criteria on distractibility in schizophrenia. J Psychiatr Res. 1978;14:81–91. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(78)90010-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Silverstein SM, Matteson S, Knight RA. Reduced top-down influence in auditory perceptual organization in schizophrenia. J Abnorm Psychol. 1996;105:663–667. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.105.4.663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Posner MI. Orienting of attention. Q J Exp Psychol. 1980;32:3–25. doi: 10.1080/00335558008248231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maruff P, Pantelis C, Danckert J, Smith D, Currie J. Deficits in the endogenous redirection of covert visual attention in chronic schizophrenia. Neuropsychologia. 1996;34:1079–1084. doi: 10.1016/0028-3932(96)00035-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Maruff P, Danckert J, Pantelis C, Currie J. Saccadic and attentional abnormalities in patients with schizophrenia. Psychol Med. 1998;28:1091–1100. doi: 10.1017/s0033291798007132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gold JM, Hahn B, Strauss GP, Waltz JA. Turning it upside down: areas of preserved cognitive function in schizophrenia. Neuropsychol Rev. 2009;19:294–311. doi: 10.1007/s11065-009-9098-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gold JM, Fuller RL, Robinson BM, McMahon RP, Braun EL, Luck SJ. Intact attentional control of working memory encoding in schizophrenia. J Abnorm Psychol. 2006;115:658–673. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.115.4.658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Overall JE, Gorman DR. The Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale. Psychol Rep. 1962;10:799–812. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Andreasen NC. The Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms (SANS) Iowa City, IA: University of Iowa; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hawk AB, Carpenter WT, Strauss JS. Diagnostic criteria and five-year outcome in schizophrenia: a report from the International Pilot Study of Schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1975;32:343–347. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1975.01760210077005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Addington D, Addington J, Maticka-Tyndale E, Joyce J. Reliability and validity of a depression rating scale for schizophrenics. Schizophr Res. 1992;6:201–208. doi: 10.1016/0920-9964(92)90003-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wechsler D. Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence (WASI) San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wilkinson GS, Robertson GJ. Wide Range Achievement Test (WRAT) 4. Lutz, Florida: Psychological Assessment Resources; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wechsler D. Wechsler Test of Adult Reading (WTAR) San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nuechterlein KH, Green MF. MATRICS Consensus Cognitive Battery, Manual. Los Angeles, CA: MATRICS Assessment Inc; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cowan N, Elliott EM, Saults JS, Morey CC, Mattox S, Ismajatulina A, et al. On the capacity of attention: Its estimation and its role in working memory and cognitive aptitudes. Cogn Psychol. 2005;51:42–100. doi: 10.1016/j.cogpsych.2004.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mori S, Tanaka G, Ayaka Y, Michitsuji S, Niwa H, Uemura M, et al. Preattentive and focal attentional processes in schizophrenia: a visual search study. Schizophr Res. 1996;22:69–76. doi: 10.1016/0920-9964(96)00049-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fuller RL, Luck SJ, Braun EL, Robinson BM, McMahon RP, Gold JM. Impaired control of visual attention in schizophrenia. J Abnorm Psychol. 2006;115:266–275. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.115.2.266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gold JM, Fuller RL, Robinson BM, Braun EL, Luck SJ. Impaired top-down control of visual search in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2007;94:148–155. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2007.04.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Piskulic D, Olver JS, Norman TR, Maruff P. Behavioural studies of spatial working memory dysfunction in schizophrenia: a quantitative literature review. Psychiatry Res. 2007;150:111–121. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2006.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Saperstein AM, Fuller RL, Avila MT, Adami H, McMahon RP, Thaker GK, et al. Spatial working memory as a cognitive endophenotype of schizophrenia: assessing risk for pathophysiological dysfunction. Schizophr Bull. 2006;32:498–506. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbj072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Badcock JC, Badcock DR, Read C, Jablensky A. Examining encoding imprecision in spatial working memory in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2008;100:144–152. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2007.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Place EJ, Gilmore GC. Perceptual organization in schizophrenia. J Abnorm Psychol. 1980;89:409–418. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.89.3.409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wells DS, Leventhal D. Perceptual grouping in schizophrenia: replication of Place and Gilmore. J Abnorm Psychol. 1984;93:231–234. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.93.2.231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Silverstein SM, Kovacs I, Corry R, Valone C. Perceptual organization, the disorganization syndrome, and context processing in chronic schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2000;43:11–20. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(99)00180-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kurylo DD, Pasternak R, Silipo G, Javitt DC, Butler PD. Perceptual organization by proximity and similarity in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2007;95:205–214. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2007.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rief W. Visual perceptual organization in schizophrenic patients. Br J Clin Psychol. 1991;30:359–366. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8260.1991.tb00956.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chey J, Holzman PS. Perceptual organization in schizophrenia: utilization of the Gestalt principles. J Abnorm Psychol. 1997;106:530–538. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.106.4.530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Carr VJ, Dewis SA, Lewin TJ. Illusory conjunctions and perceptual grouping in a visual search task in schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res. 1998;80:69–81. doi: 10.1016/s0165-1781(98)00050-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Uhlhaas PJ, Phillips WA, Mitchell G, Silverstein SM. Perceptual grouping in disorganized schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res. 2006;145:105–17. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2005.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cowan N. The magical number 4 in short-term memory: a reconsideration of mental storage capacity. Behav Brain Sci. 2001;24:87–114. doi: 10.1017/s0140525x01003922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vogel EK, Woodman GF, Luck SJ. Storage of features, conjunctions and objects in visual working memory. J Exp Psychol Hum Percept Perform. 2001;27:92–114. doi: 10.1037//0096-1523.27.1.92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vogel EK, Awh E. How to exploit diversity for scientific gain: Using individual differences to constrain cognitive theory. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 2008;17:171–176. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Goldman-Rakic PS. Working memory dysfunction in schizophrenia. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 1994;6:348–357. doi: 10.1176/jnp.6.4.348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gold JM, Carpenter C, Randolph C, Goldberg TE, Weinberger DR. Auditory working memory and Wisconsin Card Sorting Test performance in schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1997;54:159–165. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1997.01830140071013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Aleman A, Hijman R, de Haan EH, Kahn RS. Memory impairment in schizophrenia: a meta-analysis. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156:1358–1366. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.9.1358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Barch DM. The cognitive neuroscience of schizophrenia. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2005;1:321–353. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.1.102803.143959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lee J, Park S. Working memory impairments in schizophrenia: a meta-analysis. J Abnorm Psychol. 2005;114:599–611. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.114.4.599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Vogel EK, McCollough AW, Machizawa MG. Neural measures reveal individual differences in controlling access to working memory. Nature. 2005;438:500–503. doi: 10.1038/nature04171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Unsworth N, Schrock JC, Engle RW. Working Memory capacity and the antisaccade task: individual differences in voluntary saccade control. J Exp Psychol Learn Mem Cogn. 2004;30:1302–1321. doi: 10.1037/0278-7393.30.6.1302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Whitfield-Gabrieli S, Thermenos HW, Milanovic S, Tsuang MT, Faraone SV, McCarley RW, et al. Hyperactivity and hyperconnectivity of the default network in schizophrenia and in first-degree relatives of persons with schizophrenia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:1279–1284. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0809141106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.